George Simmel

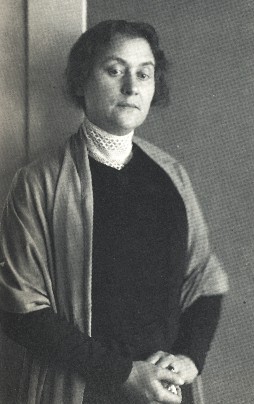

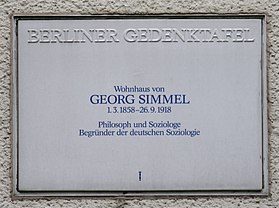

Georg Simmel (Berlin, March 1, 1858 - Strasbourg, December 12, 1918) was a German philosopher, sociologist and critic. In 1909, he and Ferdinand Tönnies, Max Weber, and Rudolf Goldscheid founded the German Sociological Society (DGS, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Soziologie).

Biography

Georg Simmel was born on March 1, 1858 in Berlin, the youngest of seven children in a Berlin merchant family. His father, Eduard Maria Simmel (1810-1874), who converted from Judaism to Catholicism, had his company & # 34; Chocolaterie Simmel & # 34; in Potsdam and was the court supplier to the King of Prussia and co-founder of the confectionery company "Felix & Sarotti", which opened in Berlin in 1852. His mother, Flora Bodstein (1818-1897), came from a Breslau family that had converted from Judaism to Protestantism. Georg Simmel was baptized in the Protestant faith and the Upbringing he received from his mother was primarily Christian. When his father died in 1874, the co-founder of 'Musik-Editions-Verlag Peters', Julius Friedländer (1827-1882), a family friend, was named his guardian. He later adopted Georg and left him a fortune that made him financially independent. After graduating from high school in Berlin in 1876, he studied history, ethnological psychology, philosophy, art history, and Old Italian as minors at the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Berlin. In 1881 he received his doctorate with the prize-winning thesis on Kant's concept of matter & # 34; The nature of matter according to Kant's physical monadology & # 34; of 1880 after a thesis originally intended as a dissertation on musical ethnology "Psychological-ethnic studies on the beginnings of music" would have been rejected.In 1885 he completed his habilitation with a thesis on "Kant's Theory of Space and Time." From 1885 he was professor of philosophy at the Friedrich Wilhelms University in Berlin. His main subjects were logic, philosophy of history, ethics, social psychology and sociology. He was a very popular speaker with a broad and subject-oriented audience.

In 1890 he married the drawing teacher, painter and writer Gertrud Kinel, who from 1900 also wrote philosophical books under the pseudonym "Maria Louise Enckendorf". Their common home in Charlottenburg-Westend became a place of intellectual exchange frequented by Rainer Maria Rilke, Edmund Husserl, Reinhold Lepsius and Sabine Lepsius, Heinrich Rickert, Marianne and Max Weber. Some of these influential friends worked to get Simmel a professorship, which both the German academic establishment and prevailing anti-Semitism tried to prevent. It was not until 1900 that Simmel received an appointment to the University of Berlin, but only to an unpaid extraordinary professorship in philosophy. He too was denied permission to take exams. In 1908 he was unable to accept a call to the University of Heidelberg because of an anti-Semitic report by the historian Dietrich Schäfer, despite Max Weber's defense.

His lectures on problems of logic, ethics, aesthetics, the sociology of religion, social psychology, and sociology were very popular. They were even advertised in the newspapers and sometimes turned into social events. Simmel's influence through his activities and networks went far beyond the issues he represented academically; Kurt Tucholsky, Siegfried Kracauer or Ernst Bloch and Theodor W. Adorno, to name just a few, highly appreciated it.

Simmel is one of those philosophers who start from predetermined ideal categories of knowledge. Advances in the sense of increasing differentiation and complexity are produced by the selection effect of evolution, as a result of which the individual also develops in historically and socially determined processes. However, a person cannot grasp the totality of life just by thinking. In 1892 his work "Introduction to the science of ethics" appeared, and in 1894 in a programmatic essay "The problem of sociology" he defined sociology as the science of processes and forms of interaction in societies. In 1900, in one of his major works, The Philosophy of Money, Simmel vividly developed the thesis that money had more and more influence on society, politics, and the individual. The expansion of the monetary economy had brought many benefits to the people, such as the overcoming of feudalism and the development of modern democracies. However, in the modern era, money has increasingly become an end in itself. Even people's self-esteem and attitudes towards life are determined by money. He ends with the realization that "money becomes God." by becoming an absolute end as an absolute means. Simmel illustrates this with a concise example: banks are now bigger and more powerful than churches.

He focused on microsociological studies, moving away from the great macrotheories of the time. He attached great importance to social interaction. "We are all fragments not only of man in general, but of ourselves." His academic life was characterized by his peripheral location at the university, as he held minor teaching positions and was appointed full professor only months before his death in 1918. Nevertheless, Simmel held and has held a central place in the German intellectual debate from 1890 to the present day. His ideas have been able to synthesize the historicist tradition of Dilthey and the Kantianism of Heinrich Rickert.

Simmel was part of the first generation of German sociologists: his neo-Kantian approach laid the foundations of sociological antipositivism, through his question "What is society?" in a direct allusion to Kant's question "What is nature?", and the presentation of pioneering analyzes of individuality and social fragmentation. For Simmel, culture referred to "cultivation of individuals through the action of external forms that have been objectified in the course of history". Simmel analyzes social and cultural phenomena in terms of "shapes" and "content" with a transitory relationship; from the content, and vice versa, depending on the context. In this sense, he was a forerunner of the structuralist style of reasoning in the social sciences. With his work on the metropolis, Simmel became a precursor of urban sociology, symbolic interactionism, and social network analysis.

Acquainted with Max Weber, Simmel wrote on the subject of personal character in a way reminiscent of the "ideal type" sociological. He broadly rejected academic standards, yet philosophically covered topics such as emotion and romantic love. Both Simmel and Weber's antipositivist theory would conform to the critical theory of the Frankfurt School.

Parallel to Leopold von Wiese, Simmel was a co-founder of formal sociology. Formal sociology aims to relate the phenomena of society as a whole to as few forms of human interaction as possible. Less importance is attached to content. It deals in particular with social connections and their relationships, for example, hierarchies in different social structures such as family, state, etc. With the essay Die Großstädte und das Geistesleben, published in 1903, Simmel became the founder of urban sociology. His essay was initially not received with much appreciation in Germany, but it had a direct influence on sociology in the United States.

During this period, Georg Simmel had a love affair with Posen's student, Gertrud Kantorowicz (1876-1945). In 1907 Angelika (Angi) was born in Bologna, the daughter of Georg Simmel and Gertrud Kantorowicz. They both agree to withhold actual paternity, and Simmel refuses to see the child. Angelika grew up with foster parents and the secret was only revealed after Georg Simmel's death in 1918.

As a social scientist, Simmel was searching for a new path. He was far removed from Auguste Comte's or Herbert Spencer's theory of a sociological organicism, as well as Leopold von Ranke's idiographic historiography.

He left no consistent philosophical or sociological system, not even a school. The latter due to the fact that he did not receive the call as a professor in Strasbourg until 1914, so until then he did not have permission to supervise doctorates or postdocs himself. Only Betty Heimann (1888–1926) and Gottfried Salomon (-Delatour) (1892–1964) were still able to do their doctorates with him in 1916, and he could no longer make use of the right to habilitation. To this end, Simmel provided many suggestions and inspiration for subsequent generations of researchers. He published more than 15 important works and 200 articles in magazines and newspapers. Simmel's individual books were translated into Italian, Russian, Polish, and French during his lifetime. In Germany he had a significant influence on young academics, including Georg Lukács, Martin Buber, Max Scheler, Karl Mannheim, and Leopold von Wiese, as well as some later members of the Frankfurt School. Simmel was a friend of the young Ernst Bloch. It was also Bloch who criticized the late Simmel's turn toward patriotism during World War I. As a philosopher, Simmel is often included in the philosophy of life. Other prominent representatives of this trend were, for example, the Frenchman Henri Bergson, whose works were translated into German at the suggestion of Simmel, or the Spanish José Ortega y Gasset. Simmel did not publish continuously as a sociologist. So between 1908 and 1917 no great sociological works appeared, but treatises on the main problems of philosophy (1910), on Goethe (1913) and Rembrandt (1916).

Together with Ferdinand Tönnies, Max Weber and Werner Sombart, he founded the German Sociological Society (DGS) in 1909. Simmel was also co-editor of the journal LOGOS, founded in 1910. International journal for the philosophy of culture.

In 1911 he received an honorary doctorate in political science from the Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg for his services to expanding knowledge of economics and in recognition of his work as one of the founders of sociology. It was not until 1914 that he was awarded a chair of philosophy at the Kaiser Wilhelm University in Strasbourg. After almost 10 years of abstinence on sociological issues, the work "Fundamental Questions of Sociology" appears in 1917. His latest publication again addresses fundamental issues of philosophical thought, social influences on people's thought and actions, also derived from his own experiences in the work "The conflict of modern culture", which appears in 1918. At the age Aged 60, Simmel died in Strasbourg on September 26, 1918 of liver cancer.

The best-known works of Simmel's work are The Problems of the Philosophy of History (1892), The Philosophy of Money (1907), The Metropolis and Mental Life (1903), Soziologie (1908, inc. The Stranger, The Social Burden, Sociology of the senses, the Sociology of space, and in the spatial projections of social forms), and Fundamental Questions of Sociology (1917). He also wrote extensively on the philosophy of Schopenhauer and Nietzsche, as well as on art, especially his book Rembrandt: An Essay on the Philosophy of Art (1916).

Basics of Simmel's theory

Levels of concern

There are four basic levels of concern in Simmel's work. First, his assumptions about the psychological mechanisms of social life. Second, his interest in the sociological mechanisms of interpersonal relationships. Third, his work on structure and changes in the Zeitgeist , the social and “cultural” spirit of his time. He also adopted the emergence principle, the idea that higher levels emerge from lower levels. Finally, he discussed his views on the nature and inevitable fate of humanity. The most microscopic work of hers dealt with the forms of interaction that take place between different types of people. Forms include subordination, superordination, exchange, conflict, and sociability.

Dialectical Thought

A dialectical approach is multicausal, multidirectional, integrates facts and values, rejects the idea that there are hard dividing lines between social phenomena. It focuses on social relationships, not only in the present, but also in the past and the future. It is deeply focused on conflicts and contradictions. Simmel's sociology refers to relationships, especially interaction, for which he was known as a methodological relationist. His principle is that everything somehow interacts with everything else. Simmel was primarily interested in dualisms, conflicts, and contradictions in whatever sphere of the social world in which he worked.

Individual conscience

Simmel focused on forms of association and paid little attention to individual consciousness. He believed in creative consciousness, a belief that can be found in various forms of interaction, in the ability of actors to create social structures, and in the disastrous effects that those structures had on the creativity of individuals. Simmel also believed that social and cultural structures came to have a life of their own.

Sociability

For Simmel, the forms of association make a mere sum of separate individuals become a society, which he describes as a superior unit made up of individuals. He was especially fascinated, it seems, by the sociability impulse in the human being, which he has described as "associations... [through which] the loneliness of individuals is resolved in union, a union with the others".

Social Geometry

In a dyad (ie, a group of two people), one person is able to retain their individuality as there is no fear that another may change the balance of the group. In contrast, triads (that is, groups of three people) run the risk of having one member subordinate to one of the other two, thus threatening her individuality. Also, if a triad lost a member, it would become a dyad.

The basic nature of this dyad-triad principle forms the essence of the structures that make up society. As a group (structure) increases in size, it becomes more isolated and segmented, so the individual also becomes more separated from each member. Regarding the notion of 'group size', Simmel's opinion was somewhat ambiguous. On the one hand, he believed that the individual benefits more when a group becomes larger, making it more difficult to exert control over the individual. On the other hand, with a larger group there is a chance that the individual may become distant and impersonal. Therefore, in an effort to cope with the larger group, he must become part of a smaller group like family.

The value of something is determined by its distance from its agent. In "The Stranger," Simmel discusses how if a person is too close to the agent, they are not considered a stranger. However, if they are too far away, they would no longer be part of a group. The particular distance of a group allows a person to have objective relationships with different members of the group.

In a chapter of his Sociology in which Simmel wonders about the results of the dominance of a large number of individuals over other individuals, a chapter in which he will be led to differentiate the action of a large number of individuals, a particular unitary formation, which in a certain way embodies an abstraction - economic collectivity, State, Church [...] and on the other hand, that of a crowd gathered punctually. This extract shows that this determinative character of the objectified social forms (which includes marriage, the State, the Church, etc.) is not of the order of a constant relationship, but is random.

"The last reason for the internal contradictions of this configuration can be formulated as follows: between the individual, with his situations and his needs on the one hand, and all the supra or infra-individual entities and the internal or external dispositions that the collective structure brings with it, on the other hand, there is no constant relationship, based on a principle, but a variable and random relationship. […] This randomness is not a coincidence, so to speak, but the logical expression of the incommensurability between these specifically individual situations that are questioned here, with all that they require, and the institutions and environments that govern or serve common life.."

Influence

It is remarkable to observe the influence of his thought in the German scientific and philosophical culture of the XX century. Figures as different as Weber, Heidegger, Jaspers, Lukács, Bloch, Emil Cioran among others, were clearly influenced by his work. The Frankfurt School theorists Hans Freyer and Max Scheler are also his intellectual heirs. Kurt Heinrich Wolff, Chairman of the International Sociological Association Research Committee on the Sociology of Knowledge, helped translate Simmel from German to English and disseminate his writings in the United States.

Some of his views

In the metropolis

One of Simmel's most notable essays is "The Metropolis and the Mental Life" ("Die Großstädte und das Geistesleben") from 1903, which was originally given as part of a series of lectures on all aspects of city life by experts in various fields, ranging from science and religion to art. The series of lectures was held in conjunction with the Dresden Cities Exhibition of 1903. Simmel was originally asked to lecture on the role of intellectual (or academic) life in the big city, but reversed the topic to analyze the effects of the big city on the mind of the individual. As a result, when the lectures were published as essays in a book, to fill the gap, the series publisher himself had to provide an essay on the original topic.

The Metropolis and Mental Life was not particularly well received during Simmel's lifetime. The exhibition organizers exaggerated their negative comments about life in the city, although Simmel also pointed to positive transformations. During the 1920s, the essay influenced the thinking of Robert E. Park and other American sociologists at the University of Chicago, who became known collectively as the "Chicago School." It gained wider circulation in the 1950s when it was translated into English and published as part of Kurt Wolff's edited collection, The Sociology of Georg Simmel. It now appears regularly on reading lists for urban studies and architectural history courses. Simmel is not quite saying that the big city has a general negative effect on the mind or the self, even as he suggests that it undergoes permanent changes. Perhaps it is this ambiguity that gave the essay a lasting place in the discourse on the metropolis.

"The deepest problems of modern life arise from the individual's attempt to maintain the independence and individuality of his existence in the face of the sovereign powers of society, in the face of the weight of historical heritage, culture and external life technique. The antagonism represents the most modern form of the conflict that primitive man had to maintain with nature for his own bodily existence. The eighteenth century may have called for the liberation of all the ties that have historically arisen in politics, religion, morality and economics to allow man's original natural virtue, which is the same in all, to develop without inhibitions. The 19th century may have sought to promote, in addition to man's freedom, his individuality (which is related to the division of labor) and his achievements that make him unique and indispensable, but at the same time make him much more dependent on activity. complementary to others. Nietzsche may have seen the tireless struggle of the individual as the prerequisite for his full development, while socialism found the same in the suppression of all competition, but in each of them the same fundamental motive was at work, namely, the resistance of the individual. individual to be leveled, engulfed by the socio-technological mechanism."

- Georg Simmel, The Metropolis and Mental Life (1903)

The philosophy of money

In this book, Simmel sees money as a component of life that helps us understand the whole of life. Simmel believed that people create value by making objects, then separating from those objects, and then trying to overcome that distance. He discovered that things that were too close were not considered valuable and things that were too far away for people to get to were not considered valuable either. In determining the value, scarcity, time, sacrifice and the difficulties involved in obtaining the object are taken into account.

For Simmel, life in the city leads to a division of labor and increased financialization. As financial transactions increase, the emphasis is on what the individual can do, rather than who the individual is. Financial issues are at stake as well as emotions.

In chapter 6 of The Philosophy of Money, Simmel talks about three social forms that, according to him, have become strongly autonomous with modernity (we could even say that, according to him, the autonomy of these three forms is the fundamental pillar of modernity). These three forms are those of law, that is, the form adopted in the modern age by normative forms of conduct; money, the modern form of exchange relations; and intellectuality, a modern form of relationships based on the transmission of knowledge. Simmel will tell us that these three forms, by empowering individuals to become an element of objective culture, will gain the power to determine forms of interaction.

"The three, law, intellectuality and money, are characterized by indifference towards individual particularity; All three extract, from the concrete totality of vital movements, an abstract, general factor, which develops according to specific and autonomous norms, and intervenes in them in the bundle of existential interests, imposing its own determination on them. Thus having the power to prescribe forms and directions to contents that by nature are indifferent to them, the three inevitably introduce into the totality of life the contradictions that concern us here. When equality seizes the formal foundations of human relations, it becomes the sharpest and most fruitful means of expressing individual inequalities; respecting the limits of formal equality, egoism has taken internal and external obstacles to its side and now possesses, with the universal validity of these determinations, a weapon that, at the service of all, also works against all."

At Simmel, the value of a product is initially based on subjective appreciation. With the increasing complexity of society, the exchange acquires the status of a social fact. To facilitate the exchange, money is necessary. The value of things is reflected in money. In it, the world of values and that of concrete things collide: "Money is the spider that weaves the social network." It is both a symbol and the cause of a comparative or relativization of all things and an externalization. Since everything can be exchanged for everything because it receives an identical measure of value, an adjustment (leveling) occurs at the same time, which no longer generates qualitative differences. The victory of money is quantity over quality, means over end. Only what has a monetary value is valuable. This is a setback, because in the end money dictates our needs and controls us instead of easing us and simplifying our lives. When money, with its lack of color and indifference, becomes the general denominator of all values, it undermines the core of things, their incomparability. In the end, the modern individual is faced with the dilemma that the objectification of life has freed him from old ties, but that he does not know how to enjoy his newly won freedom.

Analogous to earlier religions, which have given security, meaning to life, and promises for the future, money economy in modern times can be described as a new religion that affects all social and individual relationships and also dominates human emotions.

The Stranger

Simmel's concept of distance comes into play when he identifies a stranger as a person who is far and near at the same time.

"The stranger is close to us, to the extent that we feel between him and us common traits of a national, social, occupational or generally human character. But he is far from us, to the extent that these common features extend beyond him or us, and connect us only because they connect many people."

- Georg Simmel, "The Stranger" (1908)

A stranger is far enough to be unknown, but close enough to be known. In a society there must be strangers. If everyone is known, there is no person who can bring something new to everyone.

The stranger has a certain objectivity that makes them a valuable member of the individual and society. People drop their inhibitions around her and openly confess without any fear. This is because there is a belief that the stranger is not related to anyone significant and therefore does not pose a threat to the agent's life.

More generally, Simmel notes that because of their peculiar position in the group, outsiders often perform special tasks that other members of the group are unable or unwilling to perform. For example, especially in pre-modern societies, most outsiders made their living through trade, which was often viewed as an unpleasant activity by 'native' members of the community. of those societies. In some societies, they were also employed as arbitrators and judges, because they were expected to treat rival factions in the society with an impartial attitude.

"Objectivity can also be defined as freedom: the objective individual is not subject to commitments that may impair their perception, understanding and evaluation of what is given."

- Georg Simmel, "The Stranger" (1908)

On the one hand, the outsider's opinion doesn't really matter because of his lack of connection to society, but on the other hand, the outsider's opinion does matter, because of his lack of connection to society. He possesses a certain objectivity that allows him to be impartial and decide freely and without fear. He is simply able to see, think and decide without being influenced by the opinion of others.

About the secret

According to Simmel, in small groups, secrets are less necessary because everyone seems to be more similar. In larger groups, secrets are needed as a result of their heterogeneity. In secret societies, groups are held together by the need to maintain secrecy, a condition that also creates tension because the society is built on their sense of secrecy and exclusion. For Simmel, secrecy exists even in relationships as intimate as marriage. By revealing everything, the marriage becomes boring and loses all emotion. Simmel saw a general thread in the importance of secrets and the strategic use of ignorance: to be social beings capable of successfully coping with their social environment, people need clearly defined secret domains. Furthermore, sharing a common secret produces a strong "feeling" common. The modern world depends on honesty, and therefore a lie can be considered more devastating than ever. Money allows a level of secrecy never before achieved, because money allows 'invisible' transactions, due to the fact that money is now an integral part of human values and beliefs and silence can be bought.

On flirting

In his multi-layered essay, "Women, Sexuality, and Love," published in 1923, Simmel discusses flirting as a pervasive type of social interaction. According to Simmel, "defining flirting as simply a 'passion to please' it is to confuse the means to an end with the desire for that end". The distinctive character of flirting lies in the fact that it arouses delight and desire through a unique antithesis and synthesis: through the alternation of accommodation and negation. In flirting behavior, the man feels the proximity and interpenetration of the ability and inability to acquire something. This is, in essence, the "price". A sideways glance with the head half turned is characteristic of flirting at its most banal.

About fashion

In Simmel's eyes, fashion is a form of social relationship that allows those who wish to conform to the demands of a group to do so. It also allows some to be individualists by deviating from the norm. There are many social roles in fashion and both objective culture and individual culture can influence people. In the early stage everyone adopts what is fashionable and those who deviate from fashion inevitably adopt a completely new vision. what they consider fashion. Ritzer wrote about it:

"Simmel argued that following what is fashionable implies not only dualities, but also the effort of some people to be fashionable. Old-fashioned people see fashion-followers as imitators and themselves as nonconformists, but Simmel argued that the latter are simply engaging in a reverse form of imitation."

- George Ritzer, "Georg Simmel", Modern Sociological Theory (2008)

This means that those who try to be different or "unique" they are not, because by trying to be different they become part of a new group that has labeled themselves as different or "unique".

Works

- Über sociale Differenziesung, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, 1890

- Einleitung in die Moralwissenschaft, 2 vols, Berlin: Hertz, 1892-3

- Die Probleme der Geschichtphilosophie, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, 1892, 2nd edn 1905

- Philosophie des Geldes, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, 1900, 2nd edn 1907

- Die Grosstädte und das GeisteslebenDresden: Petermann, 1903

- Kant, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, 1904, 6th edn 1924

- Philosophie der Mode, Berlin: Pan-Verlag, 1905

- Kant und Goethe, Berlin: Marquardt, 1906

- Die, Frankfurt am Main: Rütten & Loening, 1906, 2nd edn 1912

- Schopenhauer und Nietzsche, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, 1907

- Schopenhauer and NietzscheUniversity of Illinois Press, 1991

- Soziologie, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, 1908

- Hauptprobleme der Philosophie, Leipzig: Göschen, 1910

- Philosophische Kultur, Leipzig: Kröner, 1911, 2nd edn 1919

- Goethe, Leipzig: Klinkhardt, 1913

- Rembrandt, Leipzig: Wolff, 1916

- Grundfragen der Soziologie, Berlin: Göschen, 1917

- Lebensanschauung, München: Duncker & Humblot, 1918

- Zur Philosophie der Kunst, Potsdam: Kiepenheur, 1922

- Fragmente und Aufsäze aus dem Nachlass, ed G Kantorowicz, München: Drei Masken Verlag, 1923

- Brücke und Tür, ed M Landmann & M Susman, Stuttgart: Koehler, 1957

- Rom, Ein ästhetische Analyse published in: Die Zeit, Wiener Wochenschrift für Politik, Vollwirtschaft Wissenschaft und Kunst, on 28 May 1898

- Florenz published in: Der2 March 1906

- Venedig published in: Der Kunstwart, Halbmonatsschau über Dichtung, Theater, Musik, bildende und angewandte Kunst. in June 1907

Spanish translations

- Fundamental Sociology Issues. Gedisa, 2009

- Liquid and Money Culture. Anthropos, 2010

- Conflict: Sociology of Antagonism. Sequitur, 2010

- The Poor. Sequitur, 2014

- The Religious Problem. Prometheus Books, 2005

- The Secret and Secret Societies. Sequitur, 2015

- Psychological and Ethnological Studies on Music. Gorla, 2003

- Philosophy of Fashion. Casimiro Libros, 2014

- Money Philosophy. Captain Swing, 2013

- Landscape philosophy. Casimiro Libros, 2013

- Goethe. Prometheus Books, 2005

- Momentan images. Gedisa, 2009

- Intuition of Life. Prometheus Books, 2014

- Religion. Gedisa, 2013

- School Pedagogy. Gedisa, 2009

- Rembrandt: Art Philosophy Test. Prometheus Books, 2006

- Rome, Florence, Venice. Gedisa, 2009

- Schopenhauer and Nietzsche. Prometheus Books, 2006

- Sociology: Studies on the Forms of Socialization. Fund for Economic Culture (Mexico), 2015

Contenido relacionado

Religion in Panama

Neoludism

Languages of the Netherlands Antilles