Generation of '98

The generation of 98 is the name by which a group of Spanish writers, essayists and poets who were profoundly affected by the moral, political and social crisis unleashed in Spain for the military defeat in the Spanish-American War and the consequent loss of Puerto Rico, Guam, Cuba and the Philippines in 1898. All the authors and great poets included in this generation were born between 1864 and 1876.

They were inspired by the critical current of canovism called regenerationism and offered an artistic vision as a whole in The generation of 98. Classics and moderns.

These authors, from the so-called Grupo de los Tres (Baroja, Azorín and Maeztu), began to write in a hypercritical and leftist youthful vein that would later be oriented towards a traditional conception of the old and new. Soon, however, controversy followed: Pío Baroja and Ramiro de Maeztu denied the existence of such a generation, and later Pedro Salinas affirmed it, after careful analysis, in his university courses and in a brief article that appeared in Revista de Occidente (December 1935), following the concept of "literary generation" defined by the German literary critic Julius Petersen; this article later appeared in his Spanish Literature. 20th century (1949). José Ortega y Gasset distinguished two generations around the dates of 1857 and 1872, one integrated by Ganivet and Unamuno and another by the younger members. His disciple Julián Marías, using the concept of "historical generation" and the central date of 1871, established that Miguel de Unamuno, Ángel Ganivet, Valle-Inclán, Jacinto Benavente, Carlos Arniches, Vicente Blasco Ibáñez, Gabriel y Galán belong to it., Manuel Gómez-Moreno, Miguel Asín Palacios, Serafín Álvarez Quintero, Pío Baroja, Azorín, Joaquín Álvarez Quintero, Ramiro de Maeztu, Manuel Machado, Antonio Machado and Francisco Villaespesa. It did not include women, but in fact Carmen de Burgos «Colombine» (1867-1932), Consuelo Álvarez Pool «Violeta» (1867-1959) and Concha Espina (1869-1955) could belong to it, since they are in that strip of dates and their characteristics coincide.

Criticism of the concept of generation was initially carried out by Juan Ramón Jiménez in a course taught in the 1950s at the University of Puerto Rico (Río Piedras), and later by an important group of critics from Federico de Onís, Ricardo Gullón, Allen W. Phillips, Ivan Schulman, and ends with the latest contributions from José Carlos Mainer, Germán Gullón, among others. All of them have questioned the opposition between the concept of the generation of '98 and modernism.

Payroll

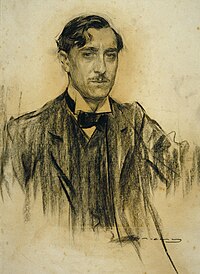

Initially formed by the so-called Group of Three (Baroja, Azorín and Maeztu), among the most significant members of this group we can mention Ángel Ganivet, Miguel de Unamuno, Enrique de Mesa, Ramiro de Maeztu, Azorín, Antonio Machado, the brothers Pío and Ricardo Baroja, Ramón María del Valle-Inclán and the philologist Ramón Menéndez Pidal. Some also include Vicente Blasco Ibáñez, who due to his aesthetics can be considered more of a writer of naturalism, and also the playwright Jacinto Benavente. Among the authors belonging to this movement are the novelist Concha Espina or the journalist Carmen de Burgos.

Artists from other disciplines can also be considered within this aesthetic, such as the painters Zuloaga, Romero de Torres and Ricardo Baroja, the latter also a writer. Among the musicians, Isaac Albéniz and Enrique Granados stand out.

Less prominent (or less studied) members of this generation were Ciro Bayo (1859-1939), the journalists, essayists and narrators Manuel Bueno (1874-1936), José María Salaverría (1873-1940) and Manuel Ciges Aparicio (1873-1936), Mauricio López-Roberts, Luis Ruiz Contreras (1863-1953), Rafael Urbano (1870-1924) and many others.

Most of the texts written during this literary period were produced in the years immediately after 1910 and are always marked by the self-justification of radicalism and youth rebellion (Machado in the last poems incorporated into Campos de Castilla, Unamuno in his articles written during World War I or in the essays by Pío Baroja).

Meeting centers

Benavente and Valle-Inclán presided over gatherings at the Café de Madrid; they were frequented by Rubén Darío, Maeztu and Ricardo Baroja. Shortly after, Benavente and his followers went to the English Brewery, while Valle-Inclán, the Machado brothers, Azorín and Pío Baroja drank the Café de Fornos. Valle-Inclán's ingenuity later led him to preside over the Café Lyon d'Or and the new Café de Levante, without a doubt the one that brought together the largest number of participants.

Magazines

The authors of the generation of '98 were grouped around some characteristic magazines, Don Quijote (1892-1902), Germinal (1897-1899), New Life (1898-1900), New Magazine (1899), Electra (1901), Helios (1903-1904) and Spanish Soul (1903-1905).

Memoir books

The authors of 98 were not very fond of talking about their peers. Pío Baroja left many memories of them in two memoirs, Youth, egotism (1917) and the seven posthumous volumes From the last turn of the road. Ricardo Baroja did the same in Gente del 98 (1952). Unamuno left several autobiographical texts about his youth, but few about his mature age.

Features

The authors of the generation maintained, at least at first, a close friendship and opposed the Spain of the Restoration; Pedro Salinas has analyzed to what extent they can truly be considered a generation historiographically speaking. What is indisputable is that they share a series of common points:

- Distinguished between Spain miserable and another Official Spain false and apparent. His concern for the identity of the Spanish is at the origin of the so-called debate about the being of Spain, which continued even in the following generations.

- They feel a great interest and love for the Castile of the abandoned and dusty peoples; they revalue their landscape and traditions, their chaste and spontaneous language. They go through the two tables writing travel books, resurrect and study Spanish literary myths and romance.

- Break and renew the classic forms of literary genres, creating new forms in all of them. In the narrative, the Nivola unamuniana, the Impressionist and Lyric novel of Azorín, which experiments with space and time and makes the same character live in several times; the open and disintegrated novel of Baroja, influenced by the folletin, or the almost theatrical and cinematographic novel of Valle-Inclán. In the theater, the sperm and the expressionism of Valle-Inclán or the philosophical dramas of Unamuno.

- They reject the aesthetics of realism and its style of broad phrase, of rhetoric and of a often detailed character, preferring a language closer to the language of the street, of shorter syntax and impressionist character; they recovered the traditional words and peasant chastes.

- They tried to acclimate in Spain the philosophical currents of European irrationalism, in particular Friedrich Nietzsche (Azorín, Maeztu, Baroja, Unamuno), Arthur Schopenhauer (especially in Baroja), Sören Kierkegaard (in Unamuno) and Henri Bergson (Antonio Machado).

- Pessimism is the most common attitude among them and the critical and dissatisfied attitude makes them sympathize with romantics like Mariano José de Larra, to whom they dedicated a tribute and Carmen de Burgos, a biography.

- Ideologically they share the thesis of regenerationism, in particular Joaquín Costa, which illustrate artistically and subjectively.

- They offer a subjective character in their works. Subjectivity is very important in the generation of 98 and modernism.

On the one hand, the most modern intellectuals, sometimes seconded by the criticized authors themselves, maintained that the generation of '98 was characterized by an increase in egotism, by a precocious and morbid feeling of frustration, by the neo-romantic exaggeration of the individuality and for his slavish imitation of the European fashions of the day.

On the other hand, for the writers of the revolutionary left of the thirties, the negative interpretation of the 1990s rebellion is linked to an ideological foundation: the end of the century spirit of protest responds to the juvenile measles of a sector of the intellectual petty bourgeoisie, condemned to return to a spiritualist and equivocal, nationalist and anti-progressive attitude. Ramón J. Sender still maintained the same thesis in 1971 (although with different assumptions).

The problems when it comes to defining the generation of '98 have always been (and are) numerous since it is not possible to cover all the artistic experiences of a long time trajectory. The reality of the moment was very complex and does not allow us to understand the generation based on the common experience of the same historical facts (basic ingredient of a generational fact). This is due to a triple reason:

- The political crisis of the end of the century XIX It affected quite a few more writers than those in the 98 generation.

- The historical experience of the authors born between 1864 and 1875 (dates of birth of Unamuno and Machado) cannot be restricted to the nationalist resentment produced by the loss of the colonies. For those years in Spain, an almost modern social and economic community was established.

- The rise of republicanism and the anticlerical struggle (1900-1910), as well as important strikes, trade unionism, workers' mobilizations or anarchist attacks.

However, it is worth asking, how is it that the generation of '98 did not take its name from modernism, since they emerged in parallel and pursued similar goals?

Historical context

The years between 1876 and 1898 are of creative boredom due to the project of the Restoration of Cánovas during the reign of Alfonso XIII. When Spain lost its colonies in 1898, society once again put its finger on the sore spot of the 1868 Revolution (Revolución de la Gloriosa). The literature of realism is stagnant and, despite its stability, political life is corrupted by the oligarchy, caciquismo, and the party regime in power, which is breaking down into internal factions within the big progressive and political parties. conservative, while a third great party, the democratic one, remains marginalized and ignored by the Canovist distribution of power. The professional prospects of the 1990s writers had reached their peak (or were doing so). The oldest are close to the age of Galdós and the youngest to that of Unamuno. This means, in contrast to the generation of '98, that they had been formed spiritually at the time of the September Revolution.

The important thing about considering them together is the fact that they have lived through two emotionally and intellectually different eras.

- The revolutionary: ideological ferment, a desire for reform and confidence in the corrective virtue of political programs.

- The restaurateur: atony of the spirits, the nickname that addresses inescapable problems, the suspicion that inspires any idea of change and the growing distrust of the current policy.

These are men doubly deceived since they saw two contradictory political structures fail (Revolution and Restoration). From these two political experiments the intellectuals of 1998 drew the same conclusion: the urgency of seeking in areas of thought and activity unrelated to politics the means of rescuing Spain from its progressive catalepsy [apparent death].

The first intellectual rejection took place at the dawn of the Restoration. In 1876 Francisco Giner de los Ríos founded the Institución Libre de Enseñanza. His task constitutes the indirect repudiation of official education, proven ineffective and insufficient at that time, and subject to the oppressive protection of political and religious interests.

The problem of the historical personality of Spain was then raised (as they did in France shortly before after the defeat of Sedan). Unamuno studied traditionalism, Ricardo Macías Picavea the "loss of personality", Rafael Altamira the psychology of the Spanish people, Joaquín Costa the historical personality of Spain...

European analogues

The 1990s authors have obvious European parallels:

- Unamuno's stillness refers to the problems experienced by André Gide.

- Valle-Inclán's galaxy theatre seems to resonate in the Irish theatre of the 1920s.

- Azorín brings together reactionary sensitivity for the cultural past (typical of Italy) and theatrical.

- Teixeira de Pascoaes is attached in many respects to the 98 Generation. He was a great friend of Unamuno.

Journalism as a habitual literary practice and the intellectual condition as a personal mood develop a new essay modality, adjusted to a theme in which evocation or the confessional frame very characteristic themes of reflection.

The crisis of the novel or of the theater are experienced with peculiar intensity in Unamuno's nivola, the collapse of the story in Azorín or by Baroja's peculiar narrative theory.

Lexicon of 98

If the generation of '98 is important in Spanish literature, it is also important for the historian of the language. In the texts of the aforementioned writers, the reality of language is appreciated, plural in circumstances and in resources. Studying the neology and neologisms of the generation of '98, it has been possible to verify the renewal of constitutive elements of Spanish, the function of the lexicon as a characterizing resource for characters and environments (chili pepper, cherry, rosette), the ingenuity of the author himself to fertilize the language ("verde-reuma" is Valle-Inclán's creation, "piscolabis" is a Barojan voice) and the latter's ability to capture the lexical innovations that arose in different fields: abracadabrante, poster, allopathy, cabaret, croupier, delicatessen, butcher, chic, slogan, blind, froufrou, makeup, mythomania, papillote, pose, vaudeville, etc.

The corpus of the 98 lexicon represents a sum of idiolects or individual linguistic systems that as a whole allow us to glimpse the evolution of Spanish since the XIX to the first half of the XX century, at a time when the standard lexicon grew by integration of words from partial lexicons (slang, technical-scientific language, see Haensch, 1997, 55). Numerous voices of 98 are generational, used by various writers of this group and later fell into disuse: cocota, batracio, bilbainismo, horizontal, rastacuerismo, rayadillo, money-scheme, intra-Spanish, catedraticin, etc. This lexicon was used by Juan Manuel de Prada in The Hero's Masks, which recreates the period. In general, they strive to contribute new ideas and to elevate the socio-cultural reality in which they were prepared to go out into other worlds to the category of a work of art. The spirit of the peoples is recovered with the word.

The generation of '98 in music

The Spanish music scene was also affected by the crisis of 1998, and was infected by the regenerationist climate fostered by the intellectuals of the time. Commendable work in this regard was carried out by the musicologist Felipe Pedrell. Already in 1897 he had written the manifesto Por Nuestra Música , and among other works of his, he published the Cancionero musical Popular Español . In addition to being the father of musicology and ethnomusicology in Spain, in the field of composition he opened the doors towards a Spanish musical nationalism, as there already existed a Russian, Bohemian, Scandinavian musical nationalism... After introducing Wagner (paradigm of German nationalism in opera) in Spain, tried to promote a nationalism analogous to the Spanish. Pedrell is better known for his work as a theoretician, musicologist, and critic than as a composer. However, musical composition probably would not have been the same without him, because he paved the way for other composers of the generation of '98 and later. Isaac Albéniz, was a virtuoso pianist who wrote the Iberia Suite, the Spanish Suite, and the opera Pepita Jiménez. Enrique Granados, also a pianist, author of Twelve Spanish Dances, and Goyescas). The virtuoso violinist Pablo Sarasate composed all kinds of works exalting the highly varied Spanish folklore, from north to south.

One can also speak of European analogues for the musicians of this period. Pedrell was known as the Spanish Wagner, while Albéniz and Sarasate were compared to Debussy and Paganini respectively.

Contenido relacionado

House of savoy

Stephen jay gould

Compass Rose