Gauss's law

In physics, Gauss's law, related to the divergence theorem or Gauss's theorem, establishes that the flux of certain fields through a closed surface is proportional to the magnitude of the sources of said field that are inside the same surface. These fields are those whose intensity decreases as the distance from the source squared. The constant of proportionality depends on the system of units used.

Applies to electrostatic and gravitational fields. Their sources are electric charge and mass, respectively. It can also be applied to the magnetostatic field.

The law was formulated by Carl Friedrich Gauss in 1835, but was not published until 1867. This is one of Maxwell's four equations, which form the basis of classical electrodynamics (the other three are Gauss's law for the magnetism, Faraday's law of induction and Ampère's law with Maxwell's correction). Gauss's law can be used to obtain Coulomb's law, and vice versa.

Flow of electric field

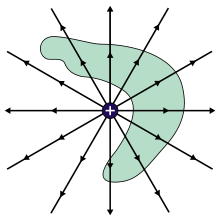

The flow (denoted as ≈ ≈ {displaystyle Phi }) is a property of any vector field referred to a hypothetical surface that can be closed or open. For an electric field, the flow (≈ ≈ E{displaystyle Phi _{E}}) is measured by the number of force lines that cross the surface.

To define electric flux precisely, consider the figure, which shows an arbitrary closed surface located within an electric field.

The surface is divided into elementary squares Δ Δ S{displaystyle Delta S}each of which is small enough to be considered a plane. These area elements can be represented as vectors Δ Δ S→ → {displaystyle {vec {delta S}}}, whose magnitude is the area itself, the direction is perpendicular to the surface and outward.

In each elementary square it is also possible to trace an electric field vector E→ → {displaystyle {vec {E}}. Since the squares are as small as you want, E{displaystyle E} can be considered constant at all points of a given square.

E→ → {displaystyle {vec {E}} and Δ Δ S→ → {displaystyle {vec {delta S}}} characterize each square and form an angle θ θ {displaystyle theta } between itself and the figure shows an amplified view of two squares.

The flow is then defined as follows:

(1)≈ ≈ E=␡ ␡ E→ → ⋅ ⋅ Δ Δ S→ → {displaystyle {Phi }_{E}=sum {vec {E}}}cdot Delta {vec {S}}}}}

That is:

(2)≈ ≈ E=♫ ♫ SE→ → ⋅ ⋅ ds→ → {displaystyle {Phi }_{E}=oint _{S}{vec {E}}}cdot d{vec {s}}}}}

Flow for a cylindrical surface in the presence of a uniform field

Suppose a cylindrical surface placed inside a uniform field E→ → {displaystyle {vec {E}} as the figure shows:

The flow ≈ ≈ E{displaystyle {Phi }_{E}} can be written as the sum of three terms, (a) an integral on the left top of the cylinder, (b) an integral on the cylindrical surface and (c) an integral on the right top:

(3)≈ ≈ E=♫ ♫ E→ → ⋅ ⋅ ds→ → =∫ ∫ (a)E→ → ⋅ ⋅ dS→ → +∫ ∫ (b)E→ → ⋅ ⋅ dS→ → +∫ ∫ (c)E→ → ⋅ ⋅ dS→ → {cHFFFFFF}{cH00FF}{cHFFFFFF}{cHFFFFFF}{cHFFFFFF}{cH00FF}{cHFFFF}{cHFFFFFF}{cHFFFF}{cHFFFF}{cHFFFF}{cHFFFF}{cHFFFFFFFFFFFF}{cHFFFFFFFF}{c}{cH00}{cH00}{cH00}{cHFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF00}{cHFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF}{cH00}{c}{c}{c}{cH00}{cH00}{cH00}{c}{c}{cH00}{cHFFFF00}{cH00}{cHFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF

For the left cap, the angle θ θ {displaystyle theta }For all points, it's from π π {displaystyle pi }, E{displaystyle E} has a constant value and vectors dS{displaystyle dS} They're all parallel.

So:

(4)∫ ∫ (a)E→ → ⋅ ⋅ dS→ → =∫ ∫ E# (π π )dS=− − E∫ ∫ dS=− − ES{displaystyle {int }_{vec {E}}}cdot d{vec {S}=int Ecos(pi)dS=-Eint dS=-ES}

being S=π π R2{displaystyle S=pi R^{2}the area of the lid. Similarly, for the right lid:

(5)∫ ∫ (c)E→ → ⋅ ⋅ dS→ → =∫ ∫ E# (0)dS=E∫ ∫ dS=ES{displaystyle {int }_{(c)}{vec {E}}}cdot d{vec {S}=int Ecos(0)dS=Eint dS=ES}

Finally, for the cylindrical surface:

(6)∫ ∫ (b)E→ → ⋅ ⋅ dS→ → =∫ ∫ E# (π π 2)dS=0{displaystyle {int }_{(b)}{vec {E}}}cdot d{vec {S}=int Ecos {bigg (}{pi over 2}{bigg)}dS=0}

Consequently: it gives zero since the same lines of force that enter, then leave the cylinder.

(7)≈ ≈ E=− − ES+0+ES=0{displaystyle {Phi }_{E}=-ES+0+ES,=0}

Flow for a spherical surface with a point charge inside it

Consider a spherical radius surface r with a timely load q in its center as shown by the figure. The electric field E→ → {displaystyle {vec {E}} is parallel to the surface vector dS→ → {displaystyle {vec {dS}}}, and the field is constant at all points of the spherical surface.

Consequently:

(8)≈ ≈ E=∫ ∫ SE→ → ⋅ ⋅ dS→ → =∫ ∫ SE# θ θ dS=∫ ∫ SE# (0)dS=E∫ ∫ SdS=E4π π r2{displaystyle Phi _{E}=int _{S}{vec {E}}{cdot d{vec {S}}}=int _{S}Ecos theta dS=int _{S}Ecos(0)dS=Eint _{S}dS=E4pi r^{2}}

Deductions

Deduction of Gauss's law from Coulomb's law

This theorem applied to the electric field created by a point charge is equivalent to Coulomb's law of electrostatic interaction.

- E=Q4π π ε ε 0r2{displaystyle E={frac {Q}{4pi epsilon _{0}r^{2}}}}}}}

Gauss' law can be derived mathematically through the use of the concept of solid angle, which is a concept very similar to the known view factors in radiation heat transfer.

The solid angle Δ Δ Ω Ω {displaystyle Delta {Omega }} which is subtended by Δ Δ A{displaystyle Delta {A}} on a spherical surface, is defined as:

Δ Δ Ω Ω =Δ Δ Ar2{displaystyle Delta {Omega }={frac {Delta {A}{r^{2}}}}}}}}

being r{displaystyle r} the radius of the sphere.

as the total area of the sphere is 4π π r2{displaystyle 4pi r^{2}} the solid angle for ‘all the sphere’ is:

Δ Δ Ω Ω =Δ Δ Ar2=4π π r2r2=4π π {displaystyle Delta {omega }={frac {Delta {A}{r^{2}}}}={frac {4pi r^{2}}{r^{2}}}}}}=4pi }

the unit of this angle is the steradian (sr)

If the area Δ Δ A{displaystyle Delta {A}} is not perpendicular to the lines that come from the origin that subsides to Δ Δ Ω Ω {displaystyle Delta {Omega }}, the normal projection is sought, which is:

Δ Δ Ω Ω =Δ Δ An^ ^ ⋅ ⋅ r^ ^ r2=Δ Δ A# θ θ r2{displaystyle Delta {omega }={frac {Delta {A{~}{hat {n}}{cdot {hat {r}}}{r^{2}}}}}}}{{frac {Delta {A}{cos {theta }{r^{2}}}}}}}{{{{{{f}}}}}{c}}}{c}{f}}}}{f}}{c}{c}{c}{c}{cd}}}}{c}{cd}}{f}}{f}}}}}}}{f}{f}}{f}{cd}{cd}}{cd}{f}}}{

If you have a "q" load surrounded by any surface, to calculate the flow going through this surface you need to find E→ → ⋅ ⋅ n^ ^ Δ Δ A{displaystyle {vec {E}}{cdot {hat {n}}{}{Delta {A}}} for each surface area element, then add them. As the surface that may be surrounding the load can be as complex as you want, it is better to find a simple relationship for this operation:

Δ Δ φ φ =E→ → ⋅ ⋅ n^ ^ Δ Δ A=Kqr2r^ ^ ⋅ ⋅ n^ ^ Δ Δ A=KqΔ Δ Ω Ω {displaystyle Delta {phi }={vec {E}}{cdot {hat {n}}{~}{delta {A}={frac {Kq}{r^{2}}}}{hat {r}}}{cdot {n}}{hat {n}}}{f}{f}{f}{f}}{f}}{f}}{f}{f}}{f}}{f}{f}}{f}}}}{f}{f}{f}}{f}{f}{f}}}{f}{f}{f}{f}}}}{f}{f}}{f}}{f}{f}{f}}{f}}{fm}{f}}{f}{f}}}}{f}}}}}}{

This way Δ Δ Ω Ω {displaystyle Delta {Omega }} is the same solid angle subsidized by a spherical surface. as shown a little higher Δ Δ Ω Ω =4π π {displaystyle delta {omega }=4pi } for any sphere, any radio. this way by adding all the flows that cross to the surface remains:

φ φ netor=♫ ♫ SE→ → ⋅ ⋅ n^ ^ dA=Kq♫ ♫ 04π π dΩ Ω =4π π Kq=qε ε 0{displaystyle phi _{neto}=oint _{S}{vec {E}{cdot {hat {n}d{A}=Kqoint _{0}^{4pi }d{omega }=4pi Kq={frac {q}{epsilon _{0}}}}}}}}}}}}}

which is the integral form of Gauss's law. Coulomb's law can also be derived from Gauss's Law.

Differential and integral form of Gauss's Law

Differential form of Gauss's law

Taking Gauss's law in integral form.

- ♫ ♫ SE→ → ⋅ ⋅ dA→ → =1ε ε or∫ ∫ Vρ ρ dV{displaystyle oint _{S}{vec {E}}}cdot d{vec {A}}}={1 over epsilon _{o}}{V}rho dV}

Applying Gauss's divergence theorem to the first term, we get

- ∫ ∫ V(► ► → → ⋅ ⋅ E→ → )dV=1ε ε or∫ ∫ Vρ ρ dV{displaystyle int _{V}({vec {nabla }}}cdot {vec {E})dV={1 over epsilon _{o}}}int _{V}rho dV}

Since both sides of the equality have volumetric differentials, and this expression must be true for any volume, it can only be that:

- ► ► → → ⋅ ⋅ E→ → =ρ ρ ε ε or{displaystyle {vec {nabla}}{cdot {vec {E}}={frac {rho }{epsilon _{o}}}}}}}}}

What is the differential form of Gauss's Law (in a vacuum).

This law can be generalized when there is a present dielectric, introducing the field of electric displacement D→ → {displaystyle {vec {D}}}, thus the Law of Gauss can be written in its most general form as

- ► ► → → ⋅ ⋅ D→ → =ρ ρ {displaystyle {vec {nabla}}cdot {vec {D}}=rho }

Ultimately, it is in this way that Gauss's law is really useful for solving complex problems in relatively simple ways.

Integral form of Gauss's law

Its integral form used in the case of an extensive charge distribution can be written as follows:

- ≈ ≈ =♫ ♫ SE→ → ⋅ ⋅ dA→ → =1ε ε or∫ ∫ Vρ ρ dV=QAε ε or{displaystyle Phi =oint _{S}{vec {E}}}cdot d{vec {A}={1 over epsilon _{o}}}int _{V}rho dV={frac {Q_{A}}{epsilon _{o}}}}}}}}}

where ≈ ≈ {displaystyle Phi } It's the electric flow, E→ → {displaystyle {vec {E}} It's the electric field, dA→ → {displaystyle d{vec {A}}} is a differential element of the area A on which the integral is carried out, QA{displaystyle Q_{mathrm {A} } is the total charge enclosed within area A, ρ ρ {displaystyle rho } is load density at a point V{displaystyle V} and ε ε or{displaystyle epsilon} is the electric permitivity of the vacuum.

Interpretation

Gauss's law can be used to show that there is no electric field inside a Faraday cage. Gauss's law is the electrostatic equivalent to Ampère's law, which is a law of magnetism. Both equations were later integrated into Maxwell's equations.

This law can be interpreted, in electrostatics, understanding the flux as a measure of the number of field lines that cross the surface in question. For a point charge this number is constant if the charge is contained by the surface and is zero if it is outside (since there are the same number of lines that enter as that leave). Furthermore, since the line density is proportional to the magnitude of the charge, it turns out that this flux is proportional to the charge, if it is enclosed, or zero, if it is not.

When we have a charge distribution, due to the superposition principle, we only have to consider the internal charges, resulting in Gauss's law.

However, although this law follows from Coulomb's law, it is more general than Coulomb's law, since it is a universal law, valid in non-electrostatic situations where Coulomb's law is not applicable.

Applications

Linear load distribution

Let be a charged line along the z axis. Let us take as a closed surface a cylinder of radius r and height h with its axis coinciding with the z axis. Expressing the field in cylindrical coordinates we have that due to the reflection symmetry with respect to a plane z=cte the field has no component in the z axis and the integration to the bases of the cylinder does not contribute, so that applying Gauss's law:

- ♫ ♫ SE→ → dS→ → =∫ ∫ SlateralE→ → dS→ → =∫ ∫ λ λ dlε ε 0{displaystyle oint _{S}{vec {E}}d{vec {S}=int _{S_{rm {lateral}}}{vec {E}d{vec {S}}}={frac {int lambda dl}{epsilon _{0}}}}}}

Due to the symmetry of the problem the field will have a radial direction and we can substitute the scalar product for the product of modules (since the direction of the lateral surface is also radial).

- ∫ ∫ SlateralEdS=E∫ ∫ SlateraldS=E2π π rh=λ λ hε ε 0{displaystyle int _{S_{rm {lateral}}}EdS=Edint _{S_{rm {lateral}}dS=E2pi rh={lambda h}{epsilon _{0}}}}}

Clearing the field and adding its radial condition we obtain:

- E→ → =λ λ 2π π rε ε 0r^ ^ {displaystyle {vec {E}}={frac {lambda }{2pi repsilon _{0}}}{hat {r}}}}{

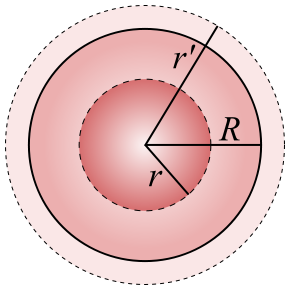

Spherical charge distribution

Consider a uniformly charged sphere of radius R. The charge inside a spherical surface of radius r is a part of the total charge, which is calculated by multiplying the charge density by the volume of the sphere of radius r:

q=ρ ρ 43π π r3{displaystyle q=rho {frac {4}{3}}pi r^{3}

If Q is the charge of the sphere of radius R, then we have:

Q=ρ ρ 43π π R3{displaystyle Q=rho {frac {4}{3}}pi R^{3}

Splitting both expressions member by member and operating appropriately:

q=Q(rR)3{displaystyle q=Q{left({frac {r}{R}}}}{3}}}

As shown in an earlier section ≈ ≈ E=E4π π r2{displaystyle {Phi }_{E},!=E4pi r^{2}}} and bearing in mind that according to the law of Gauss ≈ ≈ E=qε ε or{displaystyle {Phi }_{E},!={frac {q}{epsilon _{o}}}}}}, you get:

E4π π r2=qε ε or{displaystyle E4pi r^{2}={frac {q}{epsilon _{o}}}}}}}

Therefore, for interior points of the sphere:

| E=14π π ε ε 0Q(rR)3r2=Q4π π ε ε 0rR3{displaystyle E={frac {1}{4pi {epsilon }_{0}}}}{frac {Q{left({frac {r}{r}}}{r}}}}}{{3}}{r}}}{frac {Q}{4pi epsilon _{0}}}{frac}}{frac}}{ |

|---|

Y for exterior points:

| E=14π π ε ε 0Qr♫2{displaystyle E={frac {1}{4pi {epsilon}}}{frac {Q}{r'^{2}}}}}} |

|---|

In the event that the charge were distributed on the surface of the sphere, that is, in the event that it was conductive, for points outside it the intensity of the field would be given by the second expression, but for points interiors to the sphere, the value of the field would be null since the Gaussian surface that was considered would not enclose any charge.

Gauss's law for the magnetostatic field

As for the electric field, there is a Gauss' law for magnetism, which is expressed in its integral and differential forms as

- ♫ ♫ B→ → (r→ → )⋅ ⋅ dS→ → =0{displaystyle oint {vec {B}}({vec {r}}})cdot d{vec {s}}=0}

- ► ► ⋅ ⋅ B→ → =0{displaystyle nabla cdot {vec {B}}=0}

This law expresses the non-existence of magnetic charges or, as they are commonly known, magnetic monopoles. The distributions of magnetic sources are always neutral in the sense that they have a north pole and a south pole, so their flux through any closed surface is zero.

In the hypothetical case that the existence of monopoles were discovered experimentally, this law should be modified to accommodate the corresponding charge densities, resulting in a law completely analogous to Gauss's law for the electric field. Gauss's Law for the magnetic field would be as

- ► ► ⋅ ⋅ B→ → =ρ ρ m{displaystyle nabla cdot {vec {B}}=rho _{m}

where ρ ρ m{displaystyle rho _{m}} current density J→ → m{displaystyle {vec {J}_{m}}}which forces to amend Faraday's law

Gravitational case

Given the similarity between Newton's law of universal gravitation and Coulomb's law, an analogous law for the gravitational field can be derived, which is written

♫ ♫ G→ → (r→ → )⋅ ⋅ dS→ → =− − 4π π GMint{displaystyle oint {vec}({vec {r}}})cdot d{vec {s}}=-4pi GM_{rm {int}}}}}}}} |

► ► ⋅ ⋅ G→ → =− − 4π π Gρ ρ m{displaystyle nabla cdot {vec {G}}=-4pi Grho _{m}} |

being G the universal gravitational constant, and vector G the gravitational field. The minus sign in this law and the fact that mass is always positive means that the gravitational field is always attractive and directed towards the masses that create it.

However, unlike Gauss's law for the electric field, the gravitational case is only approximate and applies exclusively to small rest masses, for which Newton's law is valid. When Newton's theory is modified by the General Theory of Relativity, Gauss's law is no longer true, since gravitation caused by energy and the effect of the gravitational field in spacetime itself must be included (which modifies the expression of differential and integral operators).

- It is possible to compare both as we can measure the flow of properties that decrease with the square of the distance and this has in common the formula of the electric field with that of the gravitational field: =K(qr2){displaystyle =Kleft({frac {q}{r^{2}}}}{right)} and Campo Gravitatorio =G(mr2){displaystyle = gleft({frac {m}{r^{2}}}}{right)}.

Gauss's law for dielectrics

A dielectric, in the presence of an electric field, undergoes what is called polarization. Polarization consists of the separation of the positive and negative charges of the dielectric, since the electric field accelerates the positive charges in the direction of the field and the negative ones in the opposite direction. The charges generated by this polarization effect are called bound charges. The material becomes made up of dipoles, as shown in the figure. In this way, the charges are "joined" to dipoles, they are not free to move. In turn, the rest of the charges, which were not generated by this polarization effect, are called free charges. Free charges are the charges you are most used to when studying electrostatics.

Additional bibliography

- Jackson, John David (1999). Classical electrodynamic, 3.o ed., New York: Wiley.

Contenido relacionado

Anders Jonas Angström

William Watson

Sievert