Gaucho

Gaucho is the denomination used to name the characteristic inhabitant of the plains and adjacent areas of Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, Brazil (Río Grande do Sul), also for the southern zone of Chile (Los Lagos Region, Aysén Region and Magallanes Region), in the southern region of Bolivia throughout the department of Tarija and the Chuquisaqueño Chaco, in the course of the 17th century until the middle of the 19th century. He was identified by his condition as a skilled horseman and by his link with the proliferation of cattle in the region; In addition, due to the economic and cultural activities derived from it, especially the consumption of meat and the use of leather.

Regarding their occupation, the work systems imposed by some landowners after independence gave shape to the particular clientelist regime of the field laborer. And as for their way of life, they had a pseudo nomadic style.

The gaucho woman has traditionally been called "china" (from Quechua: girl and, by extension, female), "paisana", "guaina" (in the north of the coast), "gaucha" and "garment".

The figure of the gaucho in Argentine, Paraguayan and Uruguayan cultures, as well as in the Rio Grande do Sul region (Brazil) and in Chilean Patagonia is considered a national icon that represents tradition and rural customs. Gauchos fought in the independence and civil wars. The so-called gaucho literature was formed around his figure, whose main theme was the denunciation of social injustice, which culminated in the books El gaucho Martín Fierro (1872) and La Return of Martín Fierro (1879).

Because he lives in the countryside, he maintains a similarity to other rural inhabitants on horseback, and especially as a rider, such as the Chilean huaso, the Mexican charro, the Peruvian chalán, the Ecuadorian chagra, the Colombian-Venezuelan llanero, the American cowboy and the Paraguayan cowboy (the currently called "cowboy" in Paraguay has often also received, for historical-cultural reasons, the name of gaucho).

Birth

Although in the viceregal era the word gaucho or gauchesco has been used with varied meanings, with reference both to the inhabitant of rural areas of a large part of the Southern Cone (particularly of the Southern Cone on its eastern slope of the Andes), as a form of culture, in early times it was used to designate a type of inhabitant of the Sierras del Este of the Banda Oriental, called "no man's land", not only of the Pampas plain, it was also used then in what is now Río Grande del Sur, Entre Ríos, Misiones, part of Corrientes and the borders between the Spanish and Portuguese domains. The "gauchos" and their ancestors the "gauderios" and "changadores" managed to subsist by sharing and mixing with Guenoas and Guarani and other native peoples, with the natural resources of the area, and especially, by the abundant wild cattle that had reproduced in the grasslands of these territories. Originally the words vagabond or vagrant, porter, outlaw, and later, gauderíos, were used for this social group "cimarrón" and multi-ethnic.

The name "gaucho" It began to be used regularly in the last decades of the 18th century, denominating a certain independent and rebellious rural type of Creole origin, who did not obey or accept the social and work routines imposed by the authorities.

The word proper first appears in a document written in 1771 referring to certain "evildoers" who were hiding in the Sierra some distance from Maldonado, perhaps in the Sierra de los Rocha itself or its adjacencies.[citation required] It is a communication from the commander of Maldonado, Pablo Carbonell, sent to Buenos Aires to the viceroy Juan José Vértiz, dated October 23, 1771:

Very my lord; having news that some gauchos had seen the Sierra Mande to the lieutenants of Milicias Dn Jph Picolomini and Dn Clemente Puebla, they went to the Sierra with a 34-man departure among these some soldiers of the Battalion in order to make a discovery in the Sierra expressed, to see if they could find the malefactors, and at the same time saw if they could collect any.

From their "havens" in the eastern sierras, gauchos and gauderíos moved west to find troops and herds which they took east, either along the coast to the nearest Portuguese towns, or on some occasions to the coast of Castles, where they were sold to European expeditions (especially French)[citation required]. The passage of cattle from the southern half of the Banda Oriental to Brazil was possible both through the coastal areas (camino del arenal), along the lagoons, where there were also natural corners that facilitated work, and through Cuchilla Grande in lands of Cerro Largo. The area of Cerro Largo, which was a natural path, a wasteland with an undulating relief of meadows without major natural hiding places. The coastal roads, on the other hand, had numerous mountainous areas in their vicinity where the "gauchos" they could take refuge when the Spanish patrols came. The mountain ranges of Ánimas, Carapé and de la Ballena [citation needed] had the disadvantage of being too close to Maldonado's military detachments. For this reason, it is probable that the first gaucho groups took refuge in the mountainous areas of Rochense, particularly behind the Sierra de los Rocha.[citation required].

It is also worth mentioning that from the Treaty of Madrid in 1750, and until the modification of the limits a few years later, the border between Spain and Portugal had been located in the area of Los Castillos (today known as Cabo Polonium); The first setting was on a rocky point to the west of this Cape, on Buena Vista Hill, on the India Muerta Hill, and so on until reaching Cuchilla Grande.

After the aforementioned Treaty of Madrid, signed by Spain and Portugal, the missionaries of Rio Grande do Sul refused to leave the region and move south of the Uruguay River. The treaty settled the limits between the lands of the two kingdoms and the missionaries had to stay in Spanish lands. A revolt of the aborigines (alliance of Charrúas, Minuanes, Guenoas, Guarani and Jesuits against the other Europeans) broke out, known as the Guaranítica War, which only ended after the Portuguese destroyed the Eastern Missions in 1756, and the Spanish founded Salto and Maldonado. After the war, many Aborigines were left homeless, and cattle were left free to graze in the fields. These homeless aborigines became the first gauchos and after 150 years, the wild cattle spread throughout the pampas, becoming an important source of food for the vagabond gauchos.

The abandonment of the Jesuit ranches, which reached the center of the Banda Oriental to the south and the vicinity of the Atlantic to the east, made these camps become “no man's lands” and the wild cattle were illegally exploited by bold white ranchers from the region of the old Jesuit dairy farms. The slow advance of landowners from Buenos Aires, Montevideo, Santa Fe, Corrientes and Río Pardo, began to dispute the sovereignty of the prairies. The dairy farms became extinct, giving rise to the formation of organized and very fruitful production units, at a time when leather and jerky began to be in great demand, especially in the mining areas of the Planalto in southern Brazil, close to the Misiones..

The Sierra de los Rocha was the last one before reaching said border line and perhaps, for this reason, either behind or to the north of it, the first gaucho refuges would have been located.

Already in the time of the gauderíos, some years before, there was talk of a "republiqueta" of gauderíos in the Cebollatí area.[citation needed] In that place, they had "fortified the main points with cannons, moats and palisades, in the ranches that they were from the indigenous Guarani".

Etymology

There are several theories about the origin of the word, among other hypotheses, that it may have derived from the Quechua "huachu" (orphan, vagabond), from the adjective guanches or guanchos of the canaries brought in 1724 to re-found Montevideo, or from the Arabic "chaucho" (a whip used in the herding of animals). According to the researcher Mariano Polliza, it derives from the word of Portuguese origin "gauderio" with which the wandering inhabitants of the large expanses of countryside of Río Grande do Sul and the eastern Banda Oriental were designated, moving to the Río de la Plata in the XVIII century, where until then no was known, another supposed origin would be garrucho, a Portuguese word that designates an instrument used by gauchos to trap and hamstring cattle.

In Mudejar Arabic there was the word hawsh to designate the shepherd and the vagabond subject. On the other hand, the probable influence of clandestine Moorish immigrants in the genesis of gauchaje has been pointed out, as indicated by Diego de Góngora in his capitular reports to the Spanish crown. Even today in Andalusia —especially in the gypsy language Caló— they speak de gacho to name the farmer and, figuratively, the lover of a woman. In the eighteenth century, Concolorcorvo speaks of gauderios when he mentions the gauchos or huasos: & # 34; These are some young men born in Montevideo and in the neighboring countries. They try to cover up a bad shirt and worse dress with one or two ponchos...", gauderio seems to be a kind of "latinization" of the aforementioned words, Latinization associated with the Latin term —very well known then, since it was usual in the Catholic liturgy— gaudeus, which means "joy", and even " debauchery", that is to say the word "gaucho" as the word "huaso" —one metathesis of the other— seem undoubtedly multi-etymological, and forged in a specific temporal and territorial context, the livestock sector of the Southern Cone. The camiluchos also contributed to the formation of the gaucho, these were the former peons or "camilos" of the Jesuit Missions, which, when the Jesuit order was expelled in 1767 and the "reductions" were invaded, marched towards the pampean region or plain of the Argentine pampas.

Origin of the expression gaucho

According to Ricardo Rodríguez Molas: «The origin of the word gaucho, like that of so many others in the New World, has given rise to the most varied and not infrequently amazing philological theories».

An opinion that has gained strength in recent years indicates that both the word «guaso» and «gaucho» would have Hispanic roots, specifically originating in Andalusia, where the lack of grace is called «huasa»; to excess of grace, "joker"; and the peasant who would also have been the etymon of the word gaucho: "gacho". The combination of these three words would have originated the term "huaso" to refer to the Chilean country man.

The first written references to the gauchos can be found at the beginning of the 17th century, using terms such as «young men», «young men from the land», «lost boys», «vagrant boys», « Creoles of the land", "porters".

In the middle of the 17th century, the word "gauderio" to designate that social group. Shortly after the word "gaucho" appears, found written for the first time in an official document of the Banda Oriental in 1771, being already in general use by the end of the century.

The word Gaucho also appears in a document originating in Montevideo on August 8, 1780: "...that the aforementioned Díaz will not consent to the shelter of any smugglers, vagabonds or idlers known here by Gauchos".

The word gaucho apparently was initially applied in a derogatory way to designate a certain type of habitual inhabitant of the rural areas of the Southern Cone. The first writers spoke of "gauderios" (loafers) in the area, who were out of reach of the authorities; It was common for young people from different regions that today make up Argentina, Uruguay, the southern region of Brazil, and Paraguay, to engage in smuggling —without knowing that they practiced it since the boundaries between jurisdictions were very diffuse and varied almost constantly— of cattle and hides, following for their bustle, among other routes, the eastern cattle route. The vast region of the Southern Cone, barely known to the Spanish and Portuguese authorities, was also a haven for fugitives from the oppressive laws of colonial and post-colonial authorities, as well as escaped slaves. Even near the Cebollatí River, which delimits the current Uruguayan departments of Rocha and Treinta y Tres, a gaucho republic was organized, fortified with cannons.[citation required]

In the last decades of the 18th century and the first decades of the 19th century, the word gaucho spread throughout the region, to designate free workers who lived off the wild bovines or wild bovines of the pampas. Initially the term was used derogatorily, but already in the second and third decades of the XIX century, the word began to lose its connotation derogatory, hand in hand with the federalist cause initiated by José Gervasio Artigas, leading an alliance of provinces made up of the provinces of Córdoba, Corrientes, Entre Ríos, Misiones (also including the Eastern Missions at that time), the Oriental Province and that of Santa Fe.

In 1833 Charles Darwin visited the region on his famous voyage around the world aboard HMS Beagle. Darwin made extensive descriptive references to gauchos in his book A Naturalist's Voyage Round the World. The Voyage of the Beagle (A naturalist's journey around the world. The Beagle's journey), using the word without any derogatory hint and reflecting its widespread use on both banks of the Río de La Plata and even in Patagonia. Darwin, who came to meet Juan Manuel de Rosas, says that Rosas, "by adopting the clothing and habits of the gauchos, has obtained unlimited popularity in the country."

Domingo Faustino Sarmiento -whose father, José Clemente Sarmiento, could be considered a gaucho, since he worked as a muleteer between Cuyo and Chile- wrote one of the main books of Conosureño literature of the century XIX: Facundo or civilization and barbarism in the Argentine pampas, dedicated to analyzing the life of a gaucho leader such as Facundo Quiroga, associating the gaucho term to the idea of barbarism. On November 20, 1861, Sarmiento wrote to Bartolomé Miter:

"Don't try to save blood from gauchos; this is a fertilizer that needs to be useful to the country; blood is the only thing they have in human beings."

and in March 1863:

"If Colonel Sandes goes and kills people [in the provinces], shut your mouth. They are biped animals of such perverse condition that I do not know what is obtained by treating them better."

In this regard, José Ignacio García Hamilton maintains that

"The word "gaucho" in the nineteenth century had a meaning different from the present. When Sarmiento tells Mitre "do not save blood from gauchos, it is the only thing they have of human," he is talking about Urquiza, that is, a very rich businessman and rancher. Gaucho wanted to say marginal, criminal or politically intolerant. That is why Rosas and Urquiza were told gauchos in this last sense, that is, barbaric leaders, who did not allow the dissent”.

Original way of life

The gaucho's genealogy is complex; Without a doubt, the gauchos existed —although that name was not generalized— already from the times of Hernandarias, when free subjects were required to manage the numerous herds of wild cattle that thrived in the pampas dairy farms and campaigns of the Sea or Vaquerías del Mar in the XVII. These "protogauchos" they were criollos and mestizos, mostly they were "young men of the land," just like the vast majority of those who accompanied Juan de Garay in his founding of Buenos Aires, and were even the first residents of the city. However, there is a legend that mentions the "first gaucho" He complained about the bad treatment and the terrible living conditions and would have sent a letter to the King of Spain asking him to attend to his condition and those of those who were in similar circumstances. As he (obviously) received no response, —it is said— tired of waiting he approached the vacant lot that was then the Plaza Mayor and after shouting "Death to Felipe II! & # 34; he galloped off into the field. This story is almost certainly legendary, but like many legends it provides certain data to understand the origin of the gaucho.

In Brazil, historiography sometimes assumes gauchos to have Portuguese origins. The truth is that in the disputed region of the Banda Oriental, the Río Grande and the Misiones Orientales, the gauchos who herded cattle prospered, unknowingly practicing cattle smuggling between the then Spanish and Portuguese territories (the cattle went to the Brazilian & #34;Sorocaba Fair"following the Cattle Route).

The gaucho was generally nomadic and lived freely in the region, from the Pampean region, the plain that extends from the north of Argentine Patagonia to the state of Rio Grande do Sul in southern Brazil, throughout the territory gently wavy of current Uruguay, reaching the Andes to the west and even further north, through the Chaco plains to the region of Chiquitania and Santa Cruz de la Sierra. He maintained a relationship with the cattle introduced by the Europeans, a Creole equestrian complex. Most of the gauchos were criollos or mestizos, although this is not definitive. Around 1875, the Gascon traveler Henry Armaignac gave a closer definition of who was considered a gaucho. In principle, a gaucho is the rural inhabitant who has great skill as a horseman, but this is not enough. Armaignac says: & # 34; A foreigner —for example, a European— can acquire, even if it is very difficult, all the skills of a gaucho, dress like a gaucho, speak like a gaucho... but he will never be considered a gaucho; On the other hand, his children, even though all their lineages are directly European, since they are already natives or Creoles, they will be fully considered gauchos & # 34;.

La china, gaucho woman

The gaucho woman is known as china, huayna or paisana. In turn, the gaucho used to use the word garment as a synonym for a loved woman. They had large, dark eyes, though some had blue eyes, and straight, dark hair that they tied up in one or two braids. Unlike the gaucho, his character was friendly and courteous, distinguished by his sympathy and sweetness, rare elements in his male counterparts; however, she rode alongside the gaucho, even considering that she was riding from the side.

The origin

Like the gaucho, its origin was diverse and especially in times when the kidnapping of women used to be an institution in itself, which in our times and in this case, would be better understood as marriage than with the denotation current.

In many cases, the Chinese woman was of indigenous origin and hence this denomination, which used generically also meant Indian. This being her origin, literature describes her as uprooted from her peers, which also used to happen, but less frequently with the Chinese of other origins. Another case is that of the Spanish woman. she is mestizo or criolla, who either flees from her town or is kidnapped by the gaucho, either as war booty or as love booty, to which the Chinese woman often offered herself without resistance. Naturally, other times she was simply born already rooted in a gaucho lifestyle.

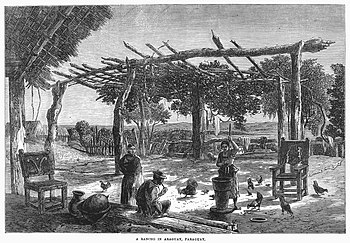

The family regime

The Chinese woman used to live with the gaucho in a semi-concubinage regime, marked by the long absence of the man, which the Chinese woman knew how to bear with stoic patience; they used to be multi-parent families. The home was made up of the rancho, which used to be a mud room with a thatched roof, without windows or chimney and a single opening without a door; In its center there was a fire that flooded everything with smoke and piled up nearby, the family ate and slept together, wrapped in their ponchos. Among the scant furniture you could find a cot, a log or a cow or horse skull to sit on, and with luck a trunk and a table to play cards. Its members lit themselves with a cow's tallow lamp and heated themselves with charcoal. The kitchen used to be in a separate building at some distance from the main ranch, as devoid as the ranch from which it is separated, there was no crockery or cutlery, they drank from an ox horn and if there was a pot with broth it was taken directly of the same, the roast was prepared strung on a wooden or metal rod.

Domestic chores

The tasks of the Chinese were agriculture and domestic tasks, taking care of the ranch and the children, among their tasks were cooking the locro, the carbonada, the stew, making fried cakes, sweets and mazamorra, according to the scarce luxury allowed it, take care of the corral populated with chickens, pigs and horses, till the land, cultivate the orchard where corn, pumpkins, watermelons, chili peppers, onions, tobacco, potatoes and some fruit trees were planted, in addition she wove ponchos and cloths, he mended the pilchas and sifted the underpants with a kind of embroidery that the gaucho wore with pride.

The gaucho, a symbol in the Southern Cone

Their participation in the independence wars

The gauchos played a fundamental role during the Argentine War of Independence, between 1810 and 1825.

Once the Primera Junta emerged in Buenos Aires, it was gauchos who followed the caudillo José Gervasio Artigas, who —although he did not initially support the patriot revolution, although soon after he was decidedly a patriot leader of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata that carries out the uprising of the Banda Oriental against the king of Spain and both Portuguese and Brazilian invaders. Artigas formed a popular army of gauchos and Indians, defeated the royalists and laid siege to the city of Montevideo and then promoted a Union of Free Peoples in the Southern Cone.

Many gauchos upheld the ideas of José Gervasio Artigas, totally revolutionary in the region, which mixed the contents of the French Enlightenment and the independence of the United States with the political and cultural legacy of the Spanish. The gauchos, along with the indigenous and other peasants, helped to establish the first federal government in the immense region of the Río de la Plata, forming the Union of Free Peoples within the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata, more appropriately a group of confederated provinces outside the centralism of Buenos Aires.

Quickly, Artigas also came into conflict with the authorities of the Directory and the Unitarians installed in the main cities and also in Buenos Aires and Montevideo. The Eastern Band, by order of Artigas, became, supported by the gauchaje, the Eastern Province in the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata. Other gauchos, on the other hand, remained faithful to the policies of the Directory.

During the war of independence, the gaucho also joined the Army of the North sent from Buenos Aires to the confines of Upper Peru of what was the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, either by collaborating by gathering information, the provision of supplies and food or giving his life in hand-to-hand combat.

Special recognition deserved the performance of the gauchos of the Argentine Northwest, Jujeños of Major General Eustoquio Díaz Vélez. During the Second Campaign to Upper Peru, commanded by General Manuel Belgrano, Díaz Vélez created, in the year 1812, a body of soldiers on horseback, made up mostly of gauchos from Jujuy, whom he called "Los Patriotas Decididos" # 3. 4; and that they were the rearguard that permanently contained the advance of the royalist armies during the Jujeño Exodus. These gauchos from Díaz Vélez also participated in the victories of the battles of Las Piedras and Tucumán, the latter the most important fought in the Argentine Independence.

When the Army of the North was defeated, General José de San Martín was appointed as the new commander, who entrusted Martín Miguel de Güemes with the defense of the northern border, while he would go to Mendoza to form the Army of the Andes (also constituted to a large extent by gauchos and huasos), with the object of crossing the Andes to liberate Chile and Peru.

The gauchos fought against the royalists in the framework of guerrilla actions that would come to be known as montoneras, along a border line of more than 600 km, which came under the responsibility of Güemes after the patriotic military collapse produced by the defeat of the Army of the North under the command of General José Rondeau, after the Battle of Sipe Sipe in 1815. The main theater of operations was the Quebrada de Humahuaca and its neighboring provinces of Tarija, Tarija then included the Chicheño horsemen from Sud Chichas.

Those fights lasted for more than ten years, this warlike action being known as the gaucho war, and it was carried out by an army made up of troops guerrilla, line and artillery, were not considered "regulars" for various reasons: being Patriots they were considered "rebels" to the Spanish empire and its crown or its liberal juntas, except for the Argentine Flag (which at that time was not recognized internationally by the powers as that of a Sovereign State); they lacked elements (fabrics, dyes, belts, etc.) that gave them uniforms except for the typical ponchos, their gaucho attire and their facones and almost improvised tacuara cane spears. As the name they accepted to receive, they almost never formed regular armies, but rather hosts of patriotic gauchos determined to give their lives for their freedom and especially for their homeland. Only in the north of Argentine territory, the gaucho military force acted in 236 combats against the Spanish colonialists and various pro-Spanish colonialists ("realistas") defending the vanguard of the border. They were also directly responsible for rejecting six of the ten invasions attempted by Spain to try to recover the domains declared independent in Tucumán in the Congress of 1816.

Historical facts indicate that their outstanding participation was crucial for Argentine independence, given that they knew how to constitute a disciplined military group within that multi-ethnic community. The blood ancestors of the northern gaucho were basically of indigenous South American, Spanish, Afro-American, and to a lesser extent Lusitano origin. Besieged by the Spanish, who were advancing from the Viceroyalty of Peru after militarily recovering almost the entire subcontinent, the northern gauchos defended the border steadfastly, characterized by strict military discipline, faithful follow-up to their chief Martín Güemes, and the demonstration of particular skills and abilities for combat on horseback and in open fighting, even in adverse environments.

Thus, the gaucho troops also constituted a very important milestone in the development of the independence of Bolivia, highlighting the guerrilla actions carried out by the commanders of the independent republiquetas, such as Manuel Ascensio Padilla and his wife, Juana Azurduy de Padilla, Eustaquio Méndez, Francisco Pérez de Uriondo, General Ignacio Warnes and the priest Ildefonso de las Muñecas, in command of guerrilla troops. These acted in close collaboration with Güemes' troops.

In Uruguay, the Luso-Brazilian occupation was defeated in 1825 by the liberating crusaders in charge of Juan Antonio Lavalleja, and achieved Independence, the product of the British and Brazilian pressures, the first Uruguayan Constitution of 1830 leaves women, slaves and illiterates (among others), and therefore the same gaucho, the same one that forged the independence sentiment. It is difficult to understand that the revolution in which the gaucho participated along with the Indian charrúa as the lieutenants of Artigas was not the same as that which the liberators of 1825 reflected in the current Uruguayan state: in fact it became blurred and new with the revolutionary ideas of Artigas, it forgot that the slaves had been free and it came in 1832 to the massacre charrúa in Salsicans in charge of the first Fr. The gaucho in Uruguay was increasingly relieved and ended up extinct with the failure of the Revolution of 1904 falling next to General Aparicio Saravia and the fenced of the camps. In the 1860s, with the support of Brazil and after a coup, the "ruguayan" government was exercised by General Venancio Flores of the Colorado Party, who agreed to power for a revolution against the legal government, exercised by the White Party. This revolution had been a crucial precedent in the War of the Triple Alliance. The Uruguayan army officers who fought in Paraguay were all supporters of the Colorados.

In southern Brazil, the gauchos unleashed a war of independence in the Rio Grande do Sul region, forming an independent republic between 1836 and 1845, maintaining slavery and creating a constitution. The Riograndense Republic was destroyed by the army of the Brazilian Empire, but the same independence sentiment has persisted in a small part of the population ever since.

In the international military historical literature, the gauchos were compared by analogy with the soldiers of the Mamluk corps from North Africa, who later formed part of Napoleon's troops when he entered Madrid in 1808.

Leading role in the history of the Southern Cone

With the dissolution of the territories of the former Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata and the respective independence of the countries of the Southern Cone, the gauchos were divided internationally, even so the cultural unity continued through the cultural manifestations that unite them. The gaucho plays an important symbolic role in shaping national sentiment and the idiosyncrasies of the region, especially in the Río de la Plata area (Argentina and Uruguay), the state of Río Grande do Sul and Chilean Patagonia. The Uruguayan poet Antonio Lussich is considered one of the precursors of gaucho poetry, and his poem "Los Tres Gauchos Orientales" was considered by Jorge Luis Borges a predecessor of the epic poem Martín Fierro, by the Argentine José Hernández. The latter, the most famous work of the genre, highlights the gaucho as a symbol of Argentine national tradition, contrasting it with the Europeanizing tendencies of the city and the corruption of the political class. Martín Fierro, the hero of the poem, is recruited by the Argentine army for the border war against "el indio", but deserts and becomes a fugitive from the law. The image of the free gaucho is often contrasted with that of the slaves who work in northern Brazil. Stereotypically, gauchos were strong (perforce, given their activities), taciturn, but arrogant and capable of responding violently to provocation. Although in southern Argentina the gauchos showed a certain indiscipline, in northern Argentina at the beginning of the XIX century they played a distinctive role, since they had a transcendental military performance in the struggles for independence from Spain. Their struggle was epically described and remembered by Leopoldo Lugones in the book The Gaucha War. In Rio Grande do Sul, the gaucho writer João Simões Lopes Neto stood out, who sought to rescue the origins of local culture by writing four main works that exalted the spirit of the gaucho in the region: Cancioneiro Guasca (1910), Contos Gauchescos (1912), Lendas do Sul (1913) and Casos do Romualdo (1914).

The gauchos also formed the troop of the "caudillos" (charismatic leaders according to Max Weber's typology) during the internal wars that followed the establishment of the independent government, in these wars the gauchos used to ascribe to the Federal Party, although on occasions, due to personal loyalties, many participated on the opposite side, after 1828 in the then newly created Uruguayan state, the gauchos found themselves divided between the whites or nationals (allied to the federals) and the colorados (allied to the unitarios), although in the Eastern State the sympathy of the gauchos was predominantly directed to the White Party, as can be seen in the battle of Masoller that occurred in 1904, in which the national or white leader Aparicio Saravia was mortally wounded.

In 1834, Charles Darwin, who toured the Argentine pampas, wrote:

"...with their long hairs to the shoulders, the black face by the wind, hat of felt, chiripá and boots taken from the rear rooms of the mares, a long facon on the back held by the belt and ate roasted meat as a main diet sometimes accompanied by a bit of mate or some cigar..."

November 10, the date on which the birth of José Hernández is remembered (in 1834), is "Tradition Day" in Argentina, and a recognition of the gaucho. It is usually celebrated with parades of horsemen in the center of the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires and equestrian skills festivals in the Mataderos neighborhood (where the cattle slaughter pens were, and in 2008, the daily parade of more than 6,000 heads of cattle, destined for refrigerators) and the properties of the Rural Society (union organization that represents large-scale ranchers) in the Federal Capital and in many localities in the interior of the country. The "Day of the Gaucho" (Law no. 24303), it is in Argentina, since 1996, on December 6, as a tribute to the 1st edition of "Martín Fierro", but it has not gained force in nativist associations at all.

Since the second half of the XIX century (in Argentina the key date, although not precise, is the battle of Caseros), in Río Grande it was when the defeat of the Riograndense Republic occurred before the empire of Brazil and in Uruguay, as in Argentina in the years 1852-1853 there was a military defeat of the parties supported by the gauchos, since then the population Gaucha went from responding to charismatic leaders to being largely patronized or sharecropped by large ranchers and other representatives of the new rulers of the time. A concrete and at the same time symbolic element marked the end of the first gaucho era: from the 1860s barbed wire began to spread, with which the gaucho's transhumance was limited.

Gaucho axiology

There is a whole gaucho axiology characterized by the following values: courage, loyalty, hospitality, hence in Argentina and Uruguay, the phrase "hacer una gauchada" whose meaning is the exact opposite of "make a guachada", although the etymology of the words gaucho and guacho could be the same, " make a gauchada" means to have a noble gesture or a good attitude while "hacer un guachada" it is the complete opposite and something that a genuine gaucho felt and feels as a dishonor.

For a part of the aristocracy and urban bourgeoisie of the XIX century (especially for adherents of the Unitary Party), the gaucho was a "dangerous savage" and the word gaucho was almost an insult to him.

An example of the gaucho idiosyncrasy of the XIX century is reflected by José Hernández (raised among gauchos) and is found in these stanzas by Martín Fierro (the gaucho idioms and words of that time are respected):

verses in Chapters II and III of the aforementioned Martin Fierro

A little more than half a century later, the writer and rancher Ricardo Güiraldes feels emotionally compelled to pay homage to the gauchos (at the beginning of the 20th century reduced to the labor category of "pawns", that is to say: of rural laborers). Despite such placement on the "social scale," Güiraldes finds himself compelled to acknowledge —with much nostalgia— the values of the gaucho. These values are put into the character of a gaucho, which he symptomatically calls "Don Segundo Sombra", and to whom he feels he owes his initiation as a man. Don Segundo Sombra is his mentor, gives him notions of special honor and respect for his neighbor, teaches him to deal with nature, and even (and this is key) is the one who protects him from his bourgeois fears and phobias. This is one of the reasons why Güiraldes, very young, concludes, after Don Segundo fired him, "I saw him leave on the horizon (...) and I left like someone bleeding to death".

The mythical gaucho

In Argentine culture, the mythical image of the Pampean gaucho stands out very strongly. His role in the country's history as well as gaucho literature have contributed to building that image. Analyzing those works, and particularly José Hernández's Martín Fierro, the aim is to understand the characteristics of the Argentine gaucho and the character associated with it. It is also interesting in its link to the myth of the cowboy or North American cowboy.

Gaucho Literature

Bartolomé Hidalgo is considered the "first poet gaucho", his Patriotic dialogues (1822) started the Gauchesca literature; Stanislao del Campo, in El Fausto Criollo, 1866, Hilario Ascasubi, in his work related to Santos Vega1870. Antonio Lussich, considered by Jorge Luis Borges (whose mother was oriental) an predecessor of the Martin Fierro, and his contempt and well-known José Hernández, one in The three Eastern gauchosThe other one in the Martin Fierro (edited both in 1872), they present an idealized gaucho, of a noble spirit, respected by the peasants by their physical and moral strength. Faustino Sarmiento Sunday, practically the son of a gaucho, in his Facundo (1845), he had a relationship of love and hatred towards the gaucho: he characterized the gaucho in good: tracer and baqueano, who lives in a state of harmony with nature; and bad: "...man divorced with society, proscribed by the laws;... savage of white color" that includes the singer, who goes "to taper in galpoon" singing his own and other exploits.

It seems that the distinction between the "good" and "bad" gaucho, within the myth, is also very relevant because it allows us to understand the paradox of this myth. Sarmiento emphasized the nomadic existence of the gaucho, his rustic behavior, his ability to survive in the pampas, whose mysterious beauty and hidden danger fascinate him, but above all he identified the inhabitant of the pampas as an uncivilized being, opposed to advancement. of progress in comparison with the refined citizens "who wear European costume, live civilized life... [where] the laws, the ideas of progress, the means of instruction..." are.

The image of the "bad gaucho" is also found in Juan Moreira, 1880, the novel by Eduardo Gutiérrez. This text relates the life of an existing and typical character of the traditional Pampas landscape: Juan Moreira. It recounts the brave games of this Argentine "Robin Hood", whose nobility contrasts with a trail of horrendous crimes and insidious deaths. However, that violence has a reason that excuses the gaucho. In Gutiérrez's work, the gaucho, a victim of society, made evil by the injustice to which he is subjected, rebels against the law. His cunning and recklessness are the basis of the Creole myth (initiated by Martín Fierro ). His social inferiority and his bad reputation force the gaucho to isolate himself, becoming a violent and antisocial being. This gaucho is called, according to the popular expression, "matrero gaucho".

Ricardo Güiraldes, in Don Segundo Sombra, 1926, once again transforms the countryside into poetry. In the words of Lugones: «Landscape and man light up in it with great brushstrokes of hope and strength. What generosity of land that engenders that life, what certainty of triumph in the great march towards happiness and beauty». By idealizing the gaucho with lyrical touches of virtue and heroism in a relationship of complete harmony with nature, he nurtures the concept that has created the stereotype of the gaucho so evoked in Argentine folklore.

If you wanted to tell the story of the bad gaucho, you would have to start with Santos Vega where the gaucho is evil and guilty, and continue with Martín Fierro where he is forced by the unjust authority to kill and fight "the party", but is finally incorporated into the System. On the other hand, in Moreira, the gaucho from Matrero becomes a fighting superhero who, mortally wounded by the police, finally dies in his own right. The line of the myth of the rebel hero still does not end there: we find, almost today, the bandit-hero Mate Cosido who, pursued in the Chaco by the police, is loved and protected by the inhabitants because he does not steal from the poor, but rather to the large exploitative companies and thus becomes a form of avenger of the oppressed. It must be considered, however, that both Juan Moreira and Mate Cosido were real people and not mere literary characters, as is the case with Martín Fierro. As for Santos Vega, the literary character seems to be based on someone who really existed, but about whom practically nothing is known.

Throughout the XX century, gaucho literature declined (although it survives, especially in the payadas and in the lyrics of folk songs), although a curious phenomenon occurs: the appearance of the gaucho in comics (these are the cases of Santos Leiva, Lindor Covas, el cimarrón, El Huinca, Fabián Leyes, etc., who present the nineteenth-century gaucho in their more virtuous aspects). These excessively idealized cartoon gauchos already had their counterpart in the visual narrative of the paintings made by Florencio Molina Campos where a more humane gauchaje is gracefully presented, in the 1970s the visual tradition that he gracefully represents while respecting the gauchaje is continued by other cartoon gauchos: El gaucho Carayá and, especially, Inodoro Pereyra (El Renegau), an excellent humorous tribute by Roberto Fontanarrosa.

The gaucho from Matrero symbolized by Martín Fierro

Since the Martín Fierro is seen as the «Gaucho Bible», it seems relevant to use it as the main basis for the analysis of the myth of the gaucho matrero.

This poem by José Hernández was written in 1872 with the title «El Gaucho Martín Fierro» and its continuation «La vuelta de Martín Fierro» came out in 1879. It has the particularity of not being written correctly in the cultured form of the language Spanish, but the gaucho's way of speaking is phonetically copied. Thanks to this epic and poetic text, the gaucho ceased to be an antisocial and "outlaw" person and gained his image as an Argentine national hero. Most likely, this poem is one of the national books of Argentines.

Firstly, this work responds to a very particular historical context, that of the beginning of the conquest of the desert. Many gauchos were forcibly incorporated into the national army. Well, that is precisely what happens to Martín Fierro at the beginning of the poem. Through this text, the author managed to make himself heard and have an echo for his proposals in favor of the gaucho's cause. It tells the story of a gaucho whose heroic and fundamentally independent character was appropriated by Argentines as a representative of a national character. He denounces with a strong critical tone the outrages to which rural outcasts were subjected.

Obeying only his desire for freedom, the hero will never agree to submit to his military commanders, which will cause his flight and his friendship with Cruz, a member of the police who becomes criminal in protecting Fierro from an unjust attack by his colleagues. Finally, they retire from the ranch with Cruz and decide to go to indigenous lands.

When reading this work, some characteristic elements of the life and customs of the gaucho appear. The gaucho is very simple with respect to his instruments: horse, facón, poncho, they cover the problem of transportation, work, defense and shelter. Each of the instruments seems to have several uses: the horse is a mount and companion, and it also serves him in fights to protect his back; the facón is an instrument of work and defense, and the poncho is used for cold and rain, for sleeping and, wrapped around one arm, for fighting. As a diet, barbecue is perfectly complemented on a dietary level with mate, a bitter yerba that is drunk as an infusion in hot water. And, to rejoice, the guitar and then the jug of gin to help oneself in "a trance". As for the gauchesque architecture, it was the austere Creole ranch made of adobe with a gabled thatched roof, the fireplace was used to "matear", cook the barbecue and warm up in winter, the round clay oven was used to make bread and other preparations, for example empanadas (the roast was done by the men, the other meals by the women); In the vicinity of the ranch there used to be a freshwater well called an aljibe (especially if it had a brocal) or "bucket" or "jagüel", there were also water troughs for the animals and palenques to hold the horses.

The gaucho, in addition to knowing how to take care of his ranch and horse and cattle, has to master an art that has something of ballet and a lot of play, where life is at stake: the criollo duel. In the Martín Fierro the duels are described, which constitute a mixture of cunning techniques, dance movements and courage bets.

Since the work of the gauchos does not require collective tasks, the only existing community is not of work but of fun and it is the octopus dances the only social moment for an isolated population. At first, the narrator asks the reader permission to sing. The need for a public, a social group that is the depositary of what is sung, is fundamental and in Martin Fierro there are dialogues between the singer and the public. Symbolic language is very rich and the whole process of narration is referred to an ecological model of the cycle of nature.

Because of the ”law of vagrancy” established since Bernardino Rivadavia, the gaucho becomes a kind of slave because, if he did not "conchaba" for food in a ranch whose boss signs "the ballot" (which certifies that he works in his ranch) when the police arrest him without a certificate they send him to the border militias for the & # 34; crime of vagrancy & # 34;. Since, on the other hand, he is absolutely denied access to the land to work it for himself, what happens is that he constitutes a mass of almost free labor, unless he chooses to rebel against this injustice by becoming a ''gaucho matrero''. ”.

The gaucho constantly lives in an outer space; the only “inside” of him was the “inside of his body”. Its habitat is the Pampas plain, which, geologically, is an alluvial plain that was filled by sedimentation. It is important to know this since the Pampean topography is a kind of "embalmed sea", as horizontal as a billiard table. Due to the insufficient precipitation of the annual rains, only low grass grows, not reaching the humidity for the formation of forests. As a consequence of all this, the gaucho (and before him, the Indian) is a kind of nomadic navigator of a green and infinite sea ("the desert" as it was called in the last century, since the existing trees were later planted by man) where he has to be guided by the sun and the stars so as not to get lost.

Gaucho folklore

On the economic basis of extensive cattle ranching, since the end of the 17th century in a large region of Argentina, in the Banda Oriental in Río Grande do Sul and in Chilean Patagonia, a culture peculiar to the area was developed, substantially identical, although in it local modalities were distinguished. This traditional cattle and equestrian culture generated a similar human and social type, the gaucho of Argentina and Uruguay, the gaucho of Rio Grande do Sul.

and Chilean Patagonia.

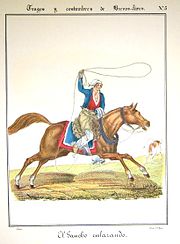

The equestrian life, the carnivorous diet, the rough weather, the tonic winds of the ocean and the pampas, breed it lean, hard and agile. Some held their hair with the Indian headband, others put the donkey belly hat on their loose hair; all wore the colt boot and the chiripá. The desert and solitude make him taciturn and silent (although according to Atahualpa Yupanqui the expert can distinguish the speech of the gaucho from the plains from the gaucho from the mountainous areas "the former speaks as if shouting to be heard better in the distances, the second, speak in a low tone to avoid avalanches"). Freedom and abundance make you haughty, hospitable and loyal. From the conquistador he receives the horse and the guitar; from the Indian the poncho, the headband, the mate, and the boleadoras. His language is a mixture of archaic Spanish with a certain influence of Andalusian and indigenous elements, to which Portuguese and African voices are added later.

The gauchos are also great riders, excellent in equestrian practices, their favorite sports being gaucho riding and gaucho dressage, duck, stable races, ring bullfighting, the game of rods, the cogoteada, the rope, and the capture by means of boleadoras and lasso from the horse, the visteo (whose gerund is vestiando) is also frequent, a mock Creole duel in which instead of facones (since they do not seek to hurt nor kill anyone in the visteo, but practice a gaucho fencing) sticks or pieces of sooty cane are used. In the XX century, gaucho games have appeared such as the chair polka, the rastrín, the game of tachos and the exercise of the boarded troupas that from being a habitual practice has become a sample of gaucho skill (the adjective "boarded" does not mean that the mounts are girded by boards or similar devices, but because in the gaucho language Traditionally, any large area of land surrounded by posts, "palos a pique" or "tables" is called "tablada" #34; within whose enclosure the equine herds are sheltered and raised).

Often a gaucho's horse was all he owned in the world. A gaucho without flete (horse) ceased to be a gaucho, something very difficult, since horses abound in the Argentine countryside.

Their tasks were basically moving cattle between grazing fields, or to market places like the port of Buenos Aires. The mistake consists of branding with the sign of the owner of the cattle. The dressage of foals was another of his usual activities. The tamer was a trade especially appreciated throughout Argentina and dressage competitions in festivals remain in force.

The gaucho's main diet was roasted beef, first, and goat as well as sheep second, although the true gaucho cooked almost any meat if necessary. The few meats that he had as taboo were those of his unconditional friends: the horse, the dog and even the domestic cat. Mainly in northwestern Argentina (although it is found in various forms throughout almost the entire country), "locro" is part of the diet, a corn-based stew (or another vegetable component) with meat. The alcoholic beverage that was mostly consumed until the end of the XIX century was gin brought in large quantities, and at affordable prices then, mainly from Holland.

The gauchos also drank the typical infusion called mate, traditionally prepared in a hollowed-out gourd, sipping the infusion through a bombilla. The water for the mate is heated (without boiling) over a stove in a container called a kettle or boiler (the two names correspond to the same container that resembles a teapot).

They used to meet in grocery stores, a provisioning place for rural areas, where they exchanged and socialized. There the neighbors of the payment and the travelers of passage met. They drank alcoholic beverages (burnt cane, gin, wine, aloja), played taba and cards (for example, the trick), or entered into various types of bloodless duels such as the malambo (originally a shoe-footing competition between men) and payadas al they are about guitars or horse races called cuadreras, or "jineteadas" of equestrian skill (ring, dressage, duck, etc.), occasionally and for various reasons (the most common were "por polleras", that is, the rivalry for the love of women) Creole duels took place at faconazos, for this eventuality almost all the gauchos frequently trained using, instead of facones, sticks with charred tips; such training is also a game often called "visteo" or "scouting" since the contestants have to quickly predict, mainly with their eyes, how the adversary will attack (see: gaucho knife fencing).

In addition to expert horsemen, muleteers, herdsmen and tamers (until the beginning of the XX century, it was common for gaucho men to start horseback riding from early childhood), many gauchos stood out for their knowledge of the territory and its climatic conditions, this ability is given the name (from the sailors of the XVI century) & #34;Baquia" and is called "baquianos" or "baqueanos" to the most expert gauchos in "baquía", another capacity close to the baquía is that of "rastreador", a tracker is one who can follow the footprint or trace of another human being or of an animal for several leagues, both qualities have been laudatoryly remembered by Domingo Faustino Sarmiento.

Many gauchos, mostly categorized by the authorities of their time as "rural bandits", have come to receive popular devotion (see: Gauchos considered miraculous (in Argentina)).

Pilchas and accoutrements

All gaucho clothing is usually called pilcha (such a word of indigenous origin later became part of lunfardo): the typical clothing of the gaucho has the imprint of that of the Andalusian horsemen, to which is added a poncho (great cape talar or blanket-type cloak with a slit in the center to pass the head through), a facón (large knife), a rebenque or talero and wide pants that are not the current ones for country men, which are called panties, but rather pajama-type pants, called underpants, loose at the bottom, which are held up by a belt with a woven wool sash and a wide leather belt sometimes adorned with coins (called a puller or harrow - because it reminds of a plow harrow) (see below harrow), are below the "chiripá", a cloth tied around the waist like a diaper, one of whose functions was to protect from the cold (the cold was called many times with the Quechua word of the same meaning: "chiri").

The poncho, the chiripá and the habit of drinking mate, were borrowed from the "indian"; The gaucho also took one of his most unique weapons from them: the boleadoras. The gaucho's hat was either the "chambergo" (wing hat), or the donkey belly hat (a circular cutout of a donkey's belly that was tied to a post and allowed to dry, then acquiring the appropriate shape); the guitar and the hat were inherited from the Spanish conquerors. The gaucho used to ride with the so-called "colt boots", which had no heels and were open at the ends, so that the toes were uncovered. Another typical element of the gaucho's clothing are their belts, the most conspicuous are called harrows and consist of wide belts of grained white leather, worked with alum. In the 17th and 19th centuries, these garments were complemented by covering the crotch with a piece of cloth like pants gathered at the waist called chiripá, apparently originating from the Argentine coast, which was held up with a harrow that was attached with various clasps, sometimes of silver metal. According to their economic or work status, this ornament used to have luxurious characteristics, even inlaid with coins or silver and gold figures.

They covered their torso with the poncho, a garment native to northern Argentina, very common also in other areas of America. Vicuña ponchos used to be very warm and light at the same time, the "pampas ponchos" (woven by the indigenous pampas practically impervious to rain), the "ponchos calamacos" woven mainly in Santiago del Estero, the red ponchos from Salta, the brown ponchos often woven with the fine hair from the belly of chulengo (guanaco calf), since the second half of the 19th century the most common — for cheap— poncho made of baize fabric, etc., the poncho used regularly and worn out was called in certain areas "poncho soró".

The later tanned leather boots with heels (strong boots) were a relatively expensive good, although most of the gauchos saved money to obtain them and wear them at patron saint festivities, national holidays and in dances. At the end of the XIX century boots used to be called "patriotic booties" since they were the same ones that the soldiers used. The boots of the northern Argentine gaucho used to and usually have folds reminiscent of a bellows, that is, with the leather leg "cordoned off", as a way of defending the forest and the possible bite of snakes. Such boots are accompanied with spurs, standing out the large silver spurs called "nazarenas" (so called because their large stingers remotely resemble the crown of thorns with which, according to the Gospels, Jesus who came from Nazareth was tortured). The ornaments with metal appliqués (virolas) were frequently billed with silver coins (patacones and rastras). The ponchos and nazarenas or lloronas (because of the noise they made among themselves) are usually true works of art to this day, although in In everyday life, the gaucho usually uses an artistically woven wool sash as a belt.

Despite the fact that there is a style of gaucho clothing that transcends time (since it is horseman's clothing prepared for harsh rural hustle and bustle), it can be said that there have been fashions for centuries: until around 1860 the gaucho almost always wore the colt boot, "underpants" or lions (a kind of pants that used to have rustic embroidery called cribing on the ankle), over the "underpants" the chiripá, a loose shirt, a scarf that, in addition to the neck, also covered the head and over the scarf a narrow leather hat called panza de burro, in the northern parts (NOA, NEA, Paraguay, Río Grande del Sur the chiripá was more common). use of hats with large "wings" to better cover the head from the sun).

Towards the aforementioned 1860s, a great change took place: as remnants of the Crimean War, a large number of baggy trousers (from the Turkish babucha) arrived in the River Plate area, currently known as panties, which had been woven in large quantities in the factories of Europe for the regiments of zouaves (the zouaves called these pants "seruel") that participated in that war, sold at a very low price they became common clothing of the gauchos (these pants, despite their thin fabric, give good thermal insulation and fold easily when walking over rough terrain or covered with tall grass), a type of baggy pants made of rustic cloth due to its grayish color, somewhat mottled. to be called "bataraz". Strong Basque immigration, which occurred in the second half of the XIX century and the first half of the XX, spread the use of the beret and espadrilles among the gauchos (particularly in the area of the humid pampas), in the XX and at the beginning of the century XXI is frequent the use of a dark hat with medium wings, similar to the hat of the huasos.

Among the "acquios" or basic equipment of the gaucho have been and are the saddles of different forms; These saddles are used mainly in mountainous areas, there being regional variations according to the terrain and climate. On relatively flat soils, the gaucho saddles had low pommels. The pommels practically disappeared in the 1870s, exposing the pair of sausages that, joined with strips of leather, were adjusted to the back of the horse. At that time, the message of clubs also arose. > and batos de sogas, in flat areas such as the pampas, the implement is more frequent, which instead of a saddle itself consists of various folded and superimposed covers on the back of the horse, from top to below, are: the cinchón or sobrecincha or pegual, the overlay, the cushion, the wide girth with top and straps from which the long stirrups hang, the bastos or loins, large smooth caronas, the slang or matra, the sweatshirt or low bottom, when the gaucho sleeps at night in the open, part of these covers serves as a rustic mat and part as a blanket.

The tens, reins, heads and shooters, with which he rides his horse are usually leather preferably from Yeguarizo braided with some ornaments or necessarily metal parts - such as the brake for tascar to the horse- (as far as possible of silver), the stirrups also vary, although they are usually made with hard woods worked: some are circular, others remember the tips of clogs, more modernly used metal studs.

It is noteworthy that the way of riding on horseback typically gaucha brings together elements of riding the rider from Norafrica and riding the brida that has Central Asian and Central European origins, the brake corresponds to the brida mode, the long stride, the horse is directed as in the rider mode with both reins however as in the flange predominates the lowest hand.

In areas where thorny plants abound (for example areas of the Chaco and the Northwest) the gauchos add large leathers to their saddles that protect their legs when they gallop, such leathers are called "guardiamontes"; In humid areas where snakes may lie in wait, they use some kind of leggings, or rather, thick leather greaves that cover a large part of the legs (this is widely observed in the province of Corrientes and in Paraguay).

Although the gauchos have used and still do use firearms (for example at the beginning of the XIX century the so-called orange blunderbuss, so called because its spout opened into a funnel the diameter of an orange, its preferred weapons have been bladed weapons, among which the large knife called facón stands out (in the Banda Oriental and in Río Grande In highly militarized areas, the saber also became quite common.) The facón is not only a weapon, but almost a tool that helps in various tasks, and the facón was added —even with more characteristics of a survival tool— the verijero.

Preservation of traditions

In the countries of the Southern Cone there are a large number of traditionalist and nativist societies that are in charge of preserving and disseminating the traditions, uses and customs of the gaucho.

In Argentina, National Gaucho Day is celebrated on December 6, commemorating the publication of the first part of El gaucho Martín Fierro, a narrative poem by José Hernández, the most important work of gaucho literature. Tradition Day is also celebrated on November 10, the date of birth of José Hernández.

In Rio Grande do Sul (Brazil) the Centers of Gaucho Traditions (CTG) were created in the middle of the XX century, with the aim of investigating and keeping alive the customs and also the gaucho art of Rio Grande do Sul. In this state every September 20 is celebrated with traditional parades on Gaucho Day (Dia do gaucho), in commemoration of the Farroupilha Revolution.

In Uruguay, the Fiesta de la Patria Gaucha is celebrated in the Laguna de las Lavanderas, Tacuarembó, among other celebrations.

In Chile there are more than thirty gaucho festivals,[citation required] including jineteadas, apialaduras and traditional festivals typical of Chilean Patagonia —specifically in the regions of Aysén and de Magallanes—, where they share with their Argentine neighbours.

In Bolivia, in the south of that country (Tarija), (Tarija has many gaucho customs), the gaucho chapaco and gaucho chaco, Creoles, have a mixture of accents similar to Cuyano, Cordoba in the central Chaco region, the Salteño, La Riojano in the West Chaco region, and the Formoseño, Chaqueño, Chaco Salteño in the Chaco region. Customs such as drinking mate and eating barbecue, dancing cueca, chacarera, etc., throughout the department of Tarija. Creole customs are practiced and encouraged in festivals and rural festivals, one of the most recognized in Bolivia is the Festival of the Chaco Tradition and, which is celebrated on the last weekend of August, among the traditional activities are: The ambrosiada, the pelada de chiva, the dressage of the colt, the pialada, and, among the gaucho games, the following are played: the taba game, the ring bullfight, and the cucaña or greasy stick. In addition to mounting clubs with music and dance.

Contenido relacionado

Cuauhtémoc

Luis de Carvajal y de la Cueva

Francis Bacon