Gastronomy of Mexico

The Mexican gastronomy is the set of dishes and culinary techniques of Mexico that are part of the traditions and common life of its inhabitants, enriched by the contributions of the different regions of the country, which derives from the experience of pre-Hispanic Mexico with European cuisine, among others. On November 16, 2010, Mexican gastronomy was recognized as Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by Unesco.

Mexican cuisine has been influenced and has influenced cuisines from other cultures, such as Spanish, French, Italian, African, Middle Eastern and Asian. It is testimony to the historical culture of the country: many dishes originated in pre-Hispanic Mexico and other important moments in its history. There is a wide range of flavors, colors, smells, textures and influences in it that make it a great attraction for nationals and foreigners: Mexico is famous for its gastronomy.

The basis of current Mexican cuisine derives largely from the cuisine existing in pre-Hispanic times, with a preponderant use of corn, beans, chili, tomato, green tomato, pumpkin, avocado, cocoa, peanuts, amaranth, vanilla, nopal, agave, cacti, herbs and condiments (epazote, hoja santa, papalo, quelites), various birds such as the turkey and a variety of mammals, fish and insects. While multiple ingredients have been adapted to Mexican cuisine through the cultural exchange brought by the Viceroyalty of New Spain and subsequent centuries, which introduced European, Mediterranean, Asian and African ingredients such as wheat, rice, coffee, cumin, mint, bay leaf, oregano, parsley, pork, beef, chicken, onion, lemon, orange, banana, sugar cane, cilantro, cinnamon, cloves, thyme and pepper; many of which have been widely adopted and even historically cultivated in Mexico, such as coffee and rice.

Mexico provided the world with products without which it would not be possible to understand world gastronomy. Among them corn, beans, chili, avocado, vanilla, cocoa, tomato, pumpkin, chayote, zapote, mamey, papaya, guava, cactus and turkey.

Diversity is the essential characteristic of Mexican cuisine, and regional food is one of its fundamental aspects. Each Mexican state and region have their own recipes and culinary traditions. Examples of regional foods are dishes such as caldillo duranguense (Durango), cochinita pibil (Yucatecan), mole oaxaqueño, mole poblano and chile en nogada (Puebla), the multiple types of pozole, the kid (from Coahuilense and Neoleón), the campechano dogfish bread, the churipo and the corundas (Purépecha region) or the menudo (Jalisciense, Michoacán, Sinaloense, Sonorense and Chihuahuense). Certainly, there are gastronomic creations that arose locally and that due to their quality, acceptance and diffusion have become emblematic of Mexican cuisine in general. This diversity is shown in the markets of each site, and the activity in the mornings begins with typical breakfasts such as sweet or salty muffins, chilaquiles and/or eggs to taste and drinks with milk, coffee, chocolate and juices, up to unique dishes of each region.

In the immense set of regional cuisines, all of them are characterized by a basic indigenous component in their ingredients and some common techniques of food preparation. The common denominator in many cuisines is the use of corn, chili and beans, accompanied by tomato in its various forms, although it is not a determinant.

Social and cultural aspects

Home cooking

The act of cooking in Mexico is considered one of the most important activities of daily life. In most of the country, especially in rural areas, food is consumed at home based on local ingredients.

Mexican gastronomy has always been described as a kitchen with a great baroque influence, the result of a culinary mix, representing the vision that Mexicans have of the world. In this way, the northern region of Mexico has a drier climate, offers a rather austere cuisine, with simple flavors, strongly based on harvesting and mixing, but which stands out for the level of floristic endemism. In contrast, in the southeast and other tropical areas, there is a wide diversity of flavors with a hitherto unknown number of local dishes and recipes.

In Mexico, it is customary to eat three meals a day: “breakfast”, “lunch” and “dinner”, if Well, since it is the industrialized country where people work the most, this has been changing and now each family applies a schedule according to their needs. On average, "breakfast" is served between 7 and 10 in the morning, "lunch" between two and three in the afternoon, and dinner after 8 at night. The "breakfast" is usually somewhat more abundant than in other countries and varies by region, from eggs prepared in different ways, alone or accompanied with beans, chilaquiles, tortas and quesadillas, to more complex dishes made with meat or stews and generally like drink juices, milk, or coffee. The main meal is the comida and usually involves the most elaborate dish of the day, generally accompanied by aguas frescas or regional drinks, although soft drinks have gained ground in recent years. The "dinner" varies according to personal customs from a simple meal accompanied by sweet bread, coffee, tea, chocolate or regional drinks, to also complex dishes or some reheating. In Mexico, "lunch" is the light food that some eat before noon, generally between ten and twelve or after breakfast, although it can be confusing since if the person delays breakfast, it is usually called lunch or even in some regions any breakfast is called that, while the "snack" is the light food between lunch and dinner, or that dinner that is usually made earlier than usual.

Festivities and rituals

The kitchen in Mexico also fulfills determining ritual and festive functions, such as the installation of the altar of the dead or the fifteen-year party. Food often clearly represents the social structure of the country.

One of the characteristics of Mexican gastronomy is that although it makes a distinction between everyday cooking and haute cuisine, these can be eaten at any time and be appropriate. Thus, although there are typical festive dishes such as mole or tamales, these can be eaten any day of the year if desired, the same in a private home or in a luxurious restaurant or in a small inn with no special ritual value; and at the same time give it that ritual value when required.

For the Day of the Dead festival, festive dishes are placed on altars and it is believed that visiting dead relatives eat the essence of the food, and if it is eaten by families later, it has lost its flavor. Any festivity or ceremony such as a wedding, quinceañera, parties or family reunions is usually a pretext for the preparation of traditional dishes, which include mole, barbecue, carnitas, mixiotes, birria or different dishes depending on the region. In ceremonies they are usually prepared to feed around five hundred guests, requiring groups of professional cooks or simply organized by the family. The kitchen is strongly designed to link families and communities.

Some very complex dishes tend to be exclusive to certain times of the year, for example at Christmas and the last days of the year, dinner becomes the most important meal and varies from more complex regional dishes (tamales with some distinction, pozole and other dishes), romeritos, Christmas Eve turkey or cod, accompanied by fritters and other desserts and sweets, piñatas filled with fruit and sweets are broken, and more native recipes as drinks, such as Christmas fruit punch, champurrado and atole. This pattern of “celebrating the traditional” is repeated in other festivals of the year. As it is a mostly Catholic country, towns and communities usually have patron saint days and festivals, in which they eat in a special way. Local fairs are another example of a local festivity, practically any town and city celebrates one, where people give gastronomy a special place.

It is still very common that in Mexico gastronomy is adapted to celebrate Lent. During this period, dishes are made with simple ingredients and everyday vegetables such as potatoes, zucchini and squash blossoms, sweet potatoes, green beans, poblano peppers, avocado, nopal and other indigenous ingredients and products, the consumption of beans, lentils, broad beans, chickpeas increases., huitlacoche, charales, sardines, shrimp and all kinds of fresh or dried fish. Dishes such as pipián or shrimp pancakes with nopales are typical of these dates and it can be more difficult to find them during the rest of the year.

In recent years, gastronomic festivals have become frequent, ranging from local to national fairs, among the most recognized are:

- International Paste Festival, the first week of October in Mineral del Monte, Hidalgo;

- Zacatlán Manzana Fair, second half of August, in Zacatlán, Puebla;

- Fair of the Strawberries, the first and second week of March, in Irapuato, Guanajuato;

- Fair of the Alfeñique, between October and November, in Toluca;

- International Festival of Beer, the second weekend of May, in Morelia, Michoacán;

- Mole International Fair, 2-3 May in Puebla;

- Mole National Fair, October, in San Pedro Atocpan, Mexico City;

- National Fair of Cheese and Wine, second half of May at the beginning of June, in Tequisquiapan, Querétaro;

- Chile Festival in Nogada, August, in the main cities of Puebla;

- Chocolate Festival, last week of November, in Villahermosa, Tabasco;

- Artisanal Cheese Festival, July in Tenosique, Tabasco;

- Sabor is Polanco, last days of March, Polanco, Mexico City;

- Wine and Food Festival Cancun - Riviera Maya, variable between March and April, Riviera Maya;

- Gastronomic exhibition of Santiago de Anaya, the first weekend of April in Santiago de Anaya, Hidalgo.

Street food and restaurants

The professionalization of culinary work in Mexico is a virtue widely valued by society, giving those who practice it a special hierarchy. With few exceptions, such as the "taquero", this domain continues to be predominantly female: it is common to see women in charge of restaurant and inn kitchens who, upon acquiring the degree of excellence, are named "mayoras", a denomination that in the Viceroyalty was given to the heads of the kitchens of the haciendas and that would now be equivalent to the European chef. Indeed, multiple authors have described Mexican cuisine as a matriarchal cuisine.

Street food is very varied, ranging from appetizers to any type of traditional cuisine. You eat the same small or medium portions that work as the "snack" Mexican and can be eaten in a few minutes, to complete meals or so complex that they can only be eaten there. Tacos of any kind stand out, which Mexicans not only classify by content, but also by tortilla, region and method of preparation (al pastor, steak, arrachera, marinated, chorizo, sausage, &# 34;cabeza", tongue, suckling pig, basket or sweaty, golden, drowned, carnitas, placeros, barbecue, suadero, cecina, pepena, fish, lobster, lagoons, potosinos, pork rinds, miners, escamoles, grasshoppers, jumiles, pito, coetlas, fried kid, pejelagarto, cream, codzitos or anything and an endless list), quesadillas, pambazos, tamales, huaraches, sopes, cakes and cemitas. Since the late 20th century, the influence of American fast food has been seen in the food at many street vendors, which offer hamburgers and hot dogs.

One of the attractions of street food is the satisfaction of hunger or spontaneous craving without all the social and emotional connotation of eating at home, and clearly also influenced by the common workload of the Mexican, who wants to continue eating complex dishes of Mexican gastronomy without having the time to prepare them. Although long-term customers usually generate a friendship relationship with a chosen seller.

In urban areas, due to the integration of women into the labor force and the influence of the western lifestyle (mainly from the United States), the tradition of cooking at home has been lost. However, fondas (a Mexican version of French bistros, cheap places to eat out for lunch) are considered an urban reservoir of traditional recipes.

History

Pre-Hispanic cuisine

The first inhabitants of the current territory of Mexico at the beginning of the Lithic Stage were nomads, they survived by gathering, hunting and fishing and had a lithic technology that was constantly improving over the millennia. From this period dates the invention of the molcajete, the metate and other instruments associated with the use of seeds, as well as the development of flint and obsidian tools.

Agriculture in Mesoamerica was born in several places at the same time. The Central Valleys of Oaxaca and the Tehuacán Valley, site of the archaic Mixtec and Zapotec cultures, were one of the settings where it was developed for the first time. It is estimated that human occupation in these two sites could have occurred continuously since 10,000 BC. C.. In Coxcatlán, Puebla and other sites in Chiapas, remains of fossil maize dating from around 5,000 BC have been located. C. The southeast area of the country is now rich in archaeological sites where attests to the collection and domestication of corn, chili, squash, chia, amaranth, agave, tomato, tomatillo, and multiple herbs progressively between 8,000 and 2,000 a. C. These products allowed the birth of a sedentary lifestyle in America, which allowed a greater specialization in its handling and preparation.

In turn, peoples of Oasisamerica, northwestern Mexico, and the Great Basin of the southwestern United States continued to live by gathering and into the late 1900s or so VII achieved total sedentary lifestyle. This opened a door of intense trade between the peoples of the north with those of central and southern Mexico that continued until the Viceroyalty, allowing an intense exchange of culinary products.

Evidence of the use of cacao by the Mokaya culture has been found since 1900 BC. C.. The importance of this fruit was so great that the later Olmec and Mayan cultures gave it value as a delicacy, becoming one of the most valued products and raising it as currency. Among the animals that served as food for the Olmec culture (1500-500 BC) are opossums, monkeys, turkeys, deer, tapirs, fish, shellfish, and waterfowl. All this way of eating is revealed in his ceramics and sculpture.

The Mayan culture continued the cultivation of corn, beans and squash, which they improved and complemented with a wide variety of plants, grown in gardens or collected in the jungle. There is evidence of the first nixtamalization of maize sometime between 1500 to 1200 B.C. C. The Mayans milled cottonseed for the production of cooking oil and created prestigious crops of corn, cotton, vanilla and cocoa. They began to use the dog to hunt larger animals such as deer, and they domesticated the Creole duck and the turkey. Bees were domesticated to obtain honey and wax that was used to make stews and fermented drinks; The level of development of beekeeping by the Mayans was such that they knew the variation in the flavor of honey depending on the flowers that the bees ate.

The great cities of the Classic period such as Teotihuacán, Cholula, Monte Albán, Calakmul and Tikal created a unique historical scene. By becoming large cities, they allowed the gastronomic knowledge of many cultures to be unified in the cities and opened the door for the massive exchange of products. Many cultures specialized in the production of certain products or foods, which used to be valued by other cultures.

The arrival and development of the Mexicas in the Valley of Mexico generated a new world of gastronomic possibilities, who learned and reinvented all the culinary techniques of the millennia of development of other cultures with new technical and agricultural knowledge. There are several factors that allowed the highly specialized development of Mexica cuisine, among them being developed on a highly fertile lake area, being in the center of Mesoamerica where several cultures coexisted that allowed a great exchange of products, and later their military dominance that brought tribute in kind and products.

Corn played a very important role in the Mexica economy, serving for a time as currency. Cintéotl was the energy of corn, and reeds were venerated or offered to the god Huitzilopochtli of corn. An inestimable number of varieties were cultivated. Other important foods were chili, salt, beans, and the different varieties of amaranth and chia grains. Tortillas or tlaxcalli and tamales or tamalli had special sizes, compositions, decorations and shapes, such as butterflies and rays. They made all kinds of offerings and funeral rites where gastronomy played a very important role. During the worship of their gods, they offered corn, chia, and all kinds of plants and herbs, toasted corn or izquitl (precedent of popcorn), neat or stirred with honey and amaranth seed flour.

Amaranth or huautli was considered by the Mexicas as a special food of a spiritual type, they gave it shapes of shields, swords or gods and they ate it made into a paste with honey that can be equivalent to sweet joy current. Commonly, at the end of the festivities, figures of this food were divided and eaten as communion, a fact that scandalized the friars due to its resemblance to Christian rites, hence the cultivation of amaranth was prohibited during the Viceroyalty, without reaching to become extinct They also ate various fungi and mushrooms, especially the huitlacoche, a parasitic fungus that grows on the cob of corn. Pumpkin and its dried or toasted seeds, tomatoes and tomatillos were a common ingredient.

The Mexica diet included animals such as turkeys, pigeons, ducks, pheasants, American wild boar, gophers, rabbits and hares, iguanas, turtles, axolotls, frogs, shrimp, fish, insects, and lake crustaceans such as crayfish. A breed of dog, the xoloitzcuintle, was bred for food. Due to its lacustrine condition, fishermen were an important sector. Insects included various types of ant and the ahuautle (the roe of the axayáctl insect).

Atole and pulque were the most common drinks among society, in addition to drinks that were fermented from corn, honey, cacti or fruits. The elite of society pride themselves on not drinking them as they preferred various beverages made from cocoa. The xocolātl was one of the greatest luxuries available and became the drink of rulers, warriors and nobles. It was flavored with vanilla, honey, and an endless list of herbs and spices, including chilies.

The Mexica used to have two meals a day, although the workers could have three, one at dawn, another at approximately 9 in the morning and one at 3 in the afternoon. This is similar to the custom in contemporary Europe, but it is not clear if the intake of atole was considered a meal or not, since they could take it at any time. According to their 18-month calendar (with 20 days each), the Mexicas had a monthly festival to honor their deities, in which food offerings other than those for daily consumption were made.

A very important ceremony for the Mexica elite was the celebration of banquets. Before a banquet, servants presented scented tobacco rolls and flowers with which guests covered their heads, hands, and necks. Before starting the meal, each guest set aside a little food and left it on the ground as an offering to the goddess Tlaltecuhtli. Cigars and flowers passed from the servant's left hand to the guest's right hand, as did the plates with food, this was an imitation of the moment when a warrior received the atlatl, arrows and shield from him. The flowers delivered received different names depending on the hand with which they were delivered; The "sword flowers" passed from the left hand to the right and the "shield flowers" They went from right to left. When eating, guests would hold their bowls of sauce in their right hands, then dip tortillas or tamales in their left. The meal concluded when the chocolate was served, which was served in a gourd and a toothpick to stir it. Men and women ate separately at banquets. Wealthier hosts often received noble or military guests in rooms around a small open courtyard in which dances were also often held, some parties beginning at midnight; some guests drank chocolate or ate hallucinogenic mushrooms so they could talk about their experiences and visions to the other guests. Before dawn, the guests began to sing and burn and bury offerings in the courtyard to ensure good luck for the children. The remaining flowers, cigarettes, and food were given to the old and poor who had been invited, or to the servants.

Viceregal period

After the Conquest, the Spanish introduced a variety of foods and cooking techniques to Europe. Spanish cuisine at that time was already a mixture of ingredients due to eight centuries of Muslim conquest. The original objective of the introduction was to reproduce their home cooking, but naturally this could not be possible for multiple reasons, the overwhelming population that existed in Mexico, which in the Valley of Mexico could have amounted to 1.5 million inhabitants and in the Yucatan peninsula up to 8 to 10 million upon arrival; as well as the distance: many Spanish ingredients were not available or became expensive.

The Spanish chose to progressively introduce products and techniques in the dominated areas, creating crops of new products, and in this process, as happened in the convents, both cuisines were mixed. While the Spanish brought to Europe a “new world” of products that created a stir in the XVI century and European XVII, incorporated into New Spain foods such as olive oil, rice, wheat, oats, onions, garlic, oregano, coriander, cinnamon, cloves and many other herbs and spices. They introduced new domesticated animals, such as pigs, cows, chickens, goats, and sheep for meat and milk, displacing many pre-Hispanic meats and insects in some places. Cheese became the most important dairy product.

Among the many culinary techniques introduced, aging, the distillation of beverages in stills and the cooking technique for the creation of fried foods stood out. Among the new products that began to be cultivated successfully in Mexico were rice, coffee, and sugar cane, which completely transformed the production of sweets and beverages and began the tradition of producing local fruits in syrup.

19th century

After the Independence of Mexico, the economy was severely damaged. Some meats, especially beef, ceased to be a staple food due to its high price. Recipes are born to exalt Mexican patriotism, such as chiles en nogada that presented the colors of the new nation. Progressively after the withdrawal of Spain, the country received influence from new countries which diversified what was served on the tables.

In this century, the local market was consolidated as the main center for the sale of a wide variety of ingredients for preparing food. The market since then has served as an important center for the economy, because while it brings new products to the communities, it buys the local family product, activating the economy.

French techniques arrived in Mexico through manuals and recipe books. The manuals set the tone for beginning to create a syncretism between European and Mexican cuisine. The Mexicans adopted the use of manuals to spread tricks and recipes. The first manual appeared in 1831, which determined the cooking technique, cleanliness, and culinary customs of homes. In 1866 "The Book of Families" was published and in 1896 "El cocinero de las familias" appeared, which included Spanish-American foods. and Mexican. Most of the dishes were from Yucatan and Veracruz, which became favorite cuisines for many inhabitants. Over time there would be many more books that would elevate the tamale as one of the special Mexican dishes.

In urban areas, pulque was one of the main accompaniments to the Mexican table of all social groups. The countess and chronicler of Maximilian and Carlota, Paula Kolonitz, wrote "Wine and beer are rarely drunk, but pulque is never lacking at the table of the rich".

The elite in the time of Porfirio Díaz preferred European cuisine, without neglecting Mexican cuisine, while the rest of the population concentrated on popular dishes. The second French intervention in Mexico (1864-1867) ended up establishing a general taste for French food, which was reflected in high society, which began to imitate recipes and produce more refined desserts. Between 1876 and 1910, numerous cookbooks with a European trend were published, such as: The Mexican Cook in France, "The Newest Art of Cooking" and the "Manual de la cocina française", which revolutionized the middle-class family kitchen.

This refinement of Mexican cuisine once again created a visible style in current dishes such as the accompaniment with French fries, crepes that wrap Mexican stews, cakes covered in cream or in the manufacture of puff pastry.

20th and 21st century

The XX century begins with the Mexican Revolution and a new blow to the Mexican economy, the basic basket is born and many recipes become exclusive to the upper classes while traditional cuisine is once again in force. In post-revolutionary Mexico and after a second air of Mexican nationalism, the aristocratic taste for this traditional cuisine was born. Soft drink companies and food producing industries such as Bimbo were born. In the cities, the middle and upper class continued to maintain active bars and pastry shops. The kitchen of this century is marked by a society with an increasing workload and the adherence of women to new jobs: the order of meals was altered, the custom of taking a nap after eating was lost and the term “lunch” or lonche to refer to the quickest breakfasts.

Starting in the 1950s, the number of restaurants for the middle class grew and concepts such as “International Cuisine” became frequent. Swiss enchiladas, club sandwiches, American-style breakfasts, the buffet, paella, American fast food, and American and South American-style grills are born. At the same time that inns and places far from modernity became true reservoirs of ancient cuisine; Thus, it was common for the inhabitants of urban areas to travel to rural sites to look for traditional food with relatives or to procure products. In addition to tourism beginning to take shape.

Ice cream parlors and ice cream parlors develop. Many tortilla shops become more technical. A new Spanish immigration finds its niche in bakeries. Thanks to the importation of products such as tequila from the United States, the distilleries mature and develop. Many fruit and vegetable packaging industries are growing. Home appliances simplify the work of many kitchens.

Authorities of Mexican cuisine emerge such as Diana Kennedy, who through 8 books that became best-sellers in English-speaking countries, the world begins to study and give gastronomy a higher status mexican. Television stations and magazines presume to give housewives the best recipe. A widespread taste for traditional cuisine and the desire to preserve it was born. At the end of the XX century, importance began to be given to the image of the chef. Gastronomy schools began to appear, including studies of Mexican cuisine in their sections. Mexican cuisine is recognized as one of the most complex and complete in the world.

In the 21st century many customs of the XX are still part of the Mexican custom: finding tamales on a corner, selling bread on a bicycle or in large baskets, sweet potato carts with whistles, street vendors selling snow cones and ice cream, selling of snacks in the street with cooked dough on the comal at the moment, sale of fresh cheeses in the morning, stalls with seasonal fruit juices and a huge gastronomic street vendor.

The “New Mexican Cuisine” sometimes called “Haute Mexican Cuisine” is born, and chefs such as Alejandro Ruiz, Benito Molina, Bricio Domínguez, Daniel Ovadía, Elena Reygadas, Enrique Olvera, Jair Téllez, Jorge Vallejo, José Burela, Paulina Abascal, Patricia Quintana, Ricardo Muñoz Zurita and Roberto Ruiz, among others, have achieved international fame, positioning regional Mexican cuisines as some of the most prestigious and presenting recipes Innovative, who at the same time fight to preserve traditional techniques and ingredients, it is common to find insects, mushrooms and herbs in their restaurants that seek to exalt Mexican products. In Tijuana and other places in Baja California, fusion cuisine has emerged under the name of Baja Med, combining the typical ingredients of Mexican cuisine and fresh ingredients harvested in Baja California with Mediterranean cuisine, such as olive oil, and Asian, such as limoncillo (lemon grass). Within this framework, in 2010 traditional Mexican cuisine was named "Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity", highlighting Mexican culinary art as one of the most elaborate and highlighting small Mexican communities for their efforts to preserve traditional cuisine as a means of sustainable development.

Features

Culinary techniques and utensils

Among the utensils used are comales, metates, molcajetes and tejolotes, bowls, gourd gourds, baskets and "bules" (pots and pitchers) to transport water, everything type of fabrics and a complex development of pottery. Many of the pre-Hispanic food preparation techniques persist today and are listed below, although, as with other foods in the world, each dish or drink may have its own preparation techniques.

- Asado: roasting techniques were made directly or above a fire or furnace for the hot air to cook the food. BBQ is an example of this technique.

- Steam cooking: was useful for the manufacture of products like tamales.

- Puib cooking: cooking food in underground furnaces to prevent heat leak and generate steam. This technique is native to Yucatan, and still very practiced to prepare various dishes, including the pibil chochinite.

- Dissecting products: It was a fairly common technique to dehydrate products into the sun. Most chilies have a dry version, the technique was also used for meats and insects after some cure, so it was not difficult to adopt Spanish customs such as cecinas.

- Wrap and packaging: useful for the sale of products or cooking of herbs and vegetables. Especially tamales require some wrapping technique, which also varies from region to region, using leaves of the same elote, banana, avocado or holy grass.

- Fermentation: fermentation was common for fruits, grapes, corn, peppers, cocoa, honeys and agave species.

- Huatape or guatape: consists of a ligation technique based on adding maize mass progressively to a broth or dish to level the final thickness. This technique has different names in terms of chilpacholes, moles and broths, but nowadays the technique usually refers to thick boiled preparations of ground chili and mass of the Gulf of Mexico made with seafood, fish, chicken or other meats and even vegetables and quelites.

- Macerado en macuahuitl: the macuahuitl, which was more of a defense weapon, had a version for kitchen; or it simply became macerated with sticks. It is necessary to crush, crush and tear the meat to give it softness, and then it passes to liquids, broths and seasoned. This gives a desired consistency and flavor to meats.

- Mexclapique: technique of production of non-mass tamales, so the products should be softened in such a way that they adhere and have form inside the tamal leaf or make thicker protective layers; the technique is still used for the production of small fish tamales (such as the same mexclapique) or any amphibian or small fish.

- Mixiote: It consists of the production of a saucer (usually with meat) mixed in some sauce, adobo or chili and then steamed wrapped in a film of the maguey (hoja). This allows you to preserve all the flavors, shape and softness.

- Mole: pre-Hispanic techniques for the production of mole continue to be preserved, and are the greatest example of specializing in Mexican cuisine. No matter what version you are making, you have to make a proper selection of products, a special grinding, mixing and correct thickening, and have a perfect handling of preparation times. As is now done, there was a version that allowed the preparation of mole masses more dry, and that could be marketed to facilitate preparation.

- Molienda with metate and hand. not only useful for mass making, the technique also allowed to spray food and products.

- Nixtamalization: cooking corn kernels in lime.

- Pilte: cooking products generally on ashes, in which the dish is found on closed leaves, similar to the manufacture of tamales.

- Pinole: corn flour production technique and sweetening suitable for powder consumption.

- Pipián: mole preparation technique or sauce made from pumpkin nuggets that had to roast and grind for the preparation of a meat stew. Its popularity was such that as the mole could be marketed in powder or pasta to facilitate its trade and preparation to taste.

- Tatemar: technique of roasting of ingredients and direct food on fire or on comals that gives food smoked aromatic notes.

- Tortear: correct tortilla preparation.

- Crunched with molcajete and tejolote: useful for crushing, crushing or mixing products.

- Use of tequesquite: seasoned, cured and salty products with tequite (a natural mineral salt).

Main ingredients

Ingredients in Mexican cuisine vary by region. For example, on the coast, seafood is a determining ingredient. Chicken, beef and pork meats are always popular. The sauces are a common element, and probably the chilies, the tomato and the onion their most frequent ingredients. The food is seasoned in very variable ways. The lists of basic ingredients always vary, since the main elements are always autochthonous and regional, but the role of corn, chili and beans in these cuisines is indisputable.

Corn

Mexican society has always sought to consume corn grown in the same country, so it is the most widely planted cereal in the entire territory, reaching more than forty-two different types. In turn, each of these types It presents several varieties, reaching an approximate of more than three thousand types of the species, according to the International Center for the Improvement of Maize and Wheat. The characteristics of each breed vary according to the soil conditions, the relative humidity of the environment, the altitude and even the way it is cultivated. Although some of the oldest evidence of maize cultivation suggests that its domestication occurred in several pockets of the country at the same time, it is likely that this process was linked to the Otomangue-speaking peoples. Be that as it may, corn continues to be the basis of most Mexican cuisines, with the exception of some gastronomic traditions from northern Mexico, where corn disputes its place with wheat as the basic cereal.

The main form in which corn is consumed in Mexico is the tortilla, but it is an equally necessary input for the preparation of almost all kinds of tamales, atoles and snacks. The tortilla is used in a wide range of dishes such as chilaquiles, tostadas, quesadillas, tacos, chalupas, gorditas, huaraches and a wide variety of Mexican snacks. Elote (corn fruit) is also consumed in countless ways, ripe and fresh (elote) or tender and fresh (xilote). Mexican gastronomy has corn deeply rooted as the main element in a large number of recipes, each part of the plant is used for some purpose, and there are multiple techniques to manipulate each of these portions. The following scheme explains in a very basic way, the way in which the most common corn preparation techniques are mixed with its most frequent uses, without delving into other uses, such as industrial ones, the production of refined flours or beverages. fermented; but it serves to outline the importance of corn in culture.

| Corn plant |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Chili

It is one of the most representative ingredients of Mexican gastronomy and a fruit associated with identity, it works as a fruit, vegetable, garnish, spice and as an ingredient in sauces and larger dishes, even as a drink; Its origins date back, according to some historians, as far back as 6,000 B.C. C. and, according to the most recent investigations, its domestication was not a fact attributable to a single culture and at a single time; It occurred throughout the region known as Mesoamerica in different stages. Its knowledge and use are recorded in the codices, where it is also mentioned as a ritual medicine, since it healed some of the aspects related to the health of the soul, drove away "bad spirits" and rectified the attitudes of the "spoiled" through its smoke. Fray Bartolomé de las Casas mentioned: "Without chili, Mexicans do not believe they are eating", a phrase that is preserved in the current social collective as "if it doesn't bite, you don't know". Since ancient times there has also been a certain association with sexuality in chili. Fray Bernardino de Sahagún states that during the festivities of Macuilxóchitl "Lord of flowers, dance, games and love", the men and women who took part in During the celebration they submitted to a rigorous fast for four days and, as a precautionary measure, they refrained from eating chili and whoever broke the fast was punished by this god, who made the transgressor suffer diseases "in the secret parts ". In any case, the prohibition of eating chili during ritual fasts continues to be a common practice among some indigenous peoples. The number of species and subspecies of chile consumed in Mexico is disputed. What is true is that the common Mexican grants different attributes to each type, preferring some types for special dishes (as is the case of chiles rellenos, where by tradition Larger and less spicy chilies are used), others valued for their level of spiciness (such as the habanero chile), and others for their flavor or use in sweeter foods. It is also evident the extremely different uses that it is given as a fresh fruit or as a dry fruit, receiving different names in each case despite the fact that it is the same species. The main producers of fresh chili are Puebla, Hidalgo, Veracruz, Sonora, Guerrero and Mexico; while more than 50% of dried chili is produced in Zacatecas. Among the main varieties of fresh chili consumed are: jalapeño, serrano, poblano, habanero, bell pepper, manzano, de árbol, tabasco, chiltepin and piquín while as dry fruit Chipotle, guajillo, pasilla, ancho, rattlesnake, and tree (dry) chiles stand out.

Bean

The pod is called "bean" (from Nahuatl exotl) the seeds are called "frijoles". It was domesticated along with corn. More than 50 different varieties are consumed in the country, from white beans ("aluvias") to multiple black and brown varieties ("bayos"). It is the favorite legume of Mexican food, present in multiple appetizers, as an accompaniment to larger dishes, or even as a main dish. There are complex dishes around beans, as it has also become the main ingredient in the basic Mexican basket due to its low cost.

Cereals

Of Asian origin and brought from the XVI century, rice is a cereal that is very present on Mexican tables. Since it is more versatile than wheat, rice can constitute any of the three times of the meal, and is a frequent accompaniment to other dishes. The most widespread way of consuming rice in Mexico is arroz a la mexicana, which is not but a fried rice and then cooked in tomato sauce. However, there are many varieties of dry rice: there is white —flavored in some regions with a green tomato and onion—, green —with poblano pepper—, yellow —with saffron—, black —with black bean broth—, and It can also be accompanied with vegetables, especially in the form known as "gardener rice". Rice is also widely used in confectionery.

Of European heritage, among the cereals, wheat stands out. It disputes the status of main cereal to corn. It is mainly associated with making bread —although there is also a flour tortilla—, whether white or sweet. White bread (bolillo, telera, birote) is an essential element of common dishes such as Mexican cakes. While sweet bread —which can be found in countless forms— is the ideal accompaniment to hot drinks that are usually served for breakfast or as a snack.

Fruits, vegetables and legumes

The vegetables that fed the ancient Mexicans were mainly the quelites (quilitl), still immature plants of different botanical families (amaranthaceae, quenopodáceas, cruciferas), tender plants that were “cooked in pots” » or were eaten raw; These families include the quintoniles, the ashes, the huauhzontles, the purslane, and a plant called mexixiquilitl, which resembles watercress. The romeritos are also very important plants that have been used in different stews, especially during Lent and Christmas.

The main fruits consumed in Mexico are avocado, peanuts, guava, tomato, lemon, mango, orange, papaya, pineapple, pitahaya, pitaya, banana, watermelon, tamarind, hawthorn, tomatillo, tuna and zapote.

The basic vegetables and legumes are: onion, lettuce, chayote, garlic, pumpkins, carrots, cucumber, beans, chickpeas, lentils and peas.

Spices

A wide variety of seasonings are used to add aroma and flavor to stews, sauces, and soups. Among the elemental original spices are: achiote, epazote, avocado leaf, holy leaf, papalo, tabasco pepper, quelites and vanilla. These plants also possess medicinal properties.

Other condiments of European, Asian and African origin were incorporated, such as basil, anise, saffron, cinnamon, cloves, cumin, mint, marjoram, bay leaf, mint, oregano, parsley, pepper, thyme, among others. The wide use of coriander stands out, of which its leaves are used in a multitude of recipes to give a characteristic flavor to many dishes.

Nopal, cacti, agave and mesquite

They accompany countless dishes and drinks. The nopal has been a common ingredient in Mexican cuisine for millennia due to its quality as a common gathering plant. The nopal is found on the coat of arms of Mexico and is considered a national symbol; therefore its consumption is considered by society as a symbol of what is Mexican, present in phrases such as "nothing more Mexican than the nopal". Its fruit, the prickly pear, gained great popularity worldwide.

The cacti are representative of the cuisine of the arid zones of the country and its fruits such as pitaya and pitahaya. The domestication of the agave species is as old as that of corn and its origin has been documented in the Tehuacán Valley and in the Central Valleys of Oaxaca for thousands of years: its use is represented by mezcal and tequila, mead, pulque, juices and sweet syrups (much necessary as honey to create pre-Hispanic drinks when sugar cane was not available), honey, vinegar, brandy and atoles, it is also the ideal place for the production of maguey worms white, red maguey worms and worm salt; its use is essential for the production of mixiote, stews, desserts, some types of sugar, flavoring for tamales and bread, as yeast, condiment and in the preparation of certain types of barbecue. The mesquite continues to be an important food in the north of the country and its use was common in pre-Hispanic times, when the Chichimecas made mesquite bread with flour from the fruit of the pod. The huizache pod is also edible.

Dairy and cheeses

Dairy products and cheeses have a history that begins with the Viceroyalty of New Spain, the manufacture of cheeses arrived in the territory, which was progressively modified to adapt to European, indigenous and Creole tastes. This mixture gave rise to a series of varieties of Mexican cheeses, most made from cow's milk and a few from goats. There are between 20 to 40 types of Mexican cheese depending on how it is classified, in addition to the regional variations and home production that exist in each town. Oaxaca cheese, panela cheese, Mexican manchego cheese (which is a soft cheese made from cow or goat, different from Spanish manchego cheese made from sheep), Chihuahua cheese (of Mennonite influence), cotija cheese, ball cheese, aged cheese stand out. from Zacazonapan, Zacatecas cheese, Perote goat cheese, Balancán leek cheese and Chiapas cream cheese. There is also purely European cheese production, mainly in Guanajuato. With the advent of industrial cheese production, today many of the regional cheeses are at risk of disappearing, especially the local varieties of ranch cheese, cottage cheese, and panela. Other dairy derivatives such as artisanal yogurt, or jocoque (a product whose base is fermented milk), are also common on the table in some areas of the country, especially in Sinaloa, the Jalisco Highlands and the Comarca Lagunera.

Cocoa

Cocoa is a distinctive ingredient of Mexican gastronomy and its use dates back to pre-Olmec times (2,000-1,200 BC). In its beginnings during pre-Columbian times, a drink was made from cocoa beans, water and different varieties of chili peppers. Currently, chocolate is used as a condiment for the preparation of different varieties of moles, sweets, pastries, and in the preparation of corn-based drinks.

Meat, poultry, fish and shellfish

Mexican cuisine consists of an enormous variety of meats, such as beef, pork, venison, rabbit, armadillo, gopher, iguana, tapir, peccary (American wild boar), and birds such as quail, chicken, varieties of duck, turkey and pheasant, to name a few; although the consumption of other wild or mountain animals has been reduced over time, either due to their scarcity or the prohibition of their consumption, becoming rarities or exclusive food of small areas of the country, as is the case of the Mexican axolotl, the opossum, armadillo, loggerhead turtle, manatee, monkey and squirrel.

Mexico occupies the fourteenth place in the longest coastline, which is bathed by two different oceans, the Pacific and the Atlantic, therefore it is not surprising that fish and shellfish are protagonists in Mexican cooking recipes. On the other hand, the country is bathed by three important hydrographic slopes, so it is also common to eat fish, crustaceans and lake snails.

Among the fish most consumed by Mexicans are tuna, sardines, red snapper, mojarra, trout, sea bass, Mexican carp, among an innumerable list. In some towns near the beaches, mainly in the north of Nayarit, families gather on the seashore to grill the freshly caught fish on mangrove sticks. Housewives from all over the country use to fry the fish and then cook it in some way, so due to the demand during the mornings, it is common for all these fish to be sold in any market.

Mexico is one of the main exporters of octopus and squid and they are also common in its gastronomy. Dishes with lobster, prawns and crab are also popular, although their cost has limited them. Some molluscs such as oysters are usually eaten alive, and others such as scallops are highly valued in ceviches. Seafood soups are one of the most consumed dishes by coastal families. Shrimp is one of the most important ingredients in some local cuisines, and it is prepared in soups, roasted, fried, cooked, breaded, in empanadas, meatballs, tamales, and romeritos.

Los charales (a species of freshwater fish exclusive to the lakes of central Mexico) is frequently purchased in the markets, it can be prepared in various ways, either dried and fried (with salt and lemon), covered with dry chile, breaded, fried with egg or with garlic. They can also be prepared like other types of food, such as an omelette or fried pancakes in green sauce. They are even sold in corn husks, like tamales, these have been previously roasted over wood-fired embers.

Edible insects

As an example of the richness and diversity of Mexican food, we can mention the consumption of insects. Mexico is the country in the world in which the greatest variety of species consumed has been documented. Entomophagy shows the adaptation from traditional cuisine to a wide variety of environments or resources and is a reflection of the country's biodiversity; In addition to the fact that insects have favored other human needs such as; clothes, medicine, pest control and disintegration of organic waste.

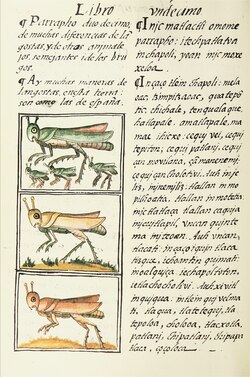

In Mexico, entomophagy has been a common practice since pre-Hispanic times, as evidenced by the Códice Florentino, written by Fray Bernardino de Sahagún, which describes the consumption of 96 species of insects edible. To date, insects continue to be consumed throughout the country (although to a greater extent in the central-southern, eastern, southeastern, and southwestern regions of the country), and are considered, in cases such as escamoles, a high-priced delicacy.

Depending on the source consulted, between 504 and 549 species of edible insects have been recorded in the country (one third of the world's culinary species), most of them in the states of Hidalgo, Oaxaca, Guerrero, State of Mexico, Mexico City, Yucatan, Puebla and Veracruz while in northern Mexico they are consumed in less variety. In multiple indigenous groups there are several terms to classify arthropods, which are not always known by the Spanish term insecto, which has made counting them difficult.

Insects are high in nutrients, pre-Hispanic cultures ate an enormous variety without realizing their great contribution in protein, polyunsaturated fatty acids, iron, essential amino acids, calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, B complex vitamins and vitamins A, C and D.

Among the most commonly consumed insects are escamoles, maguey worms, chicatana ants, axayácatl and its ahuautle, grasshoppers and jumiles, among others. All of these can be consumed in their natural form since they have a pleasant flavor, however already cooked they are even more delicious and their flavors can be better appreciated. They are prepared toasted, roasted, in tacos, in sauces, there are even restaurants in Mexico that serve them in omelettes. Although they are an excellent option for the human diet, there are still problems for their promotion given that there is no Official Mexican Standard that regulates their production, collection and distribution processes.[citation required]

Edible insects in Mexico are produced according to the time of year; for example, the chinicuiles (the larva of a butterfly found in the maguey) are "harvested" during the first rains of the year, when it starts to rain, they come out under the maguey and that is when they are collected. Currently there are populations where these insects are raised by placing a layer of live chinicuiles and another layer of corn tortillas in a clay pot. As for the maguey worms, they grow inside the stalks (the maguey leaf), so each one must be destroyed since there is approximately one worm per stalk, this is an example of why many insect foods can become expensive or eaten only seasonally.

Axayacatl and his ahuautle

The ahuautle (from Nahuatl ahuautli or ahuahutli, or in its Spanishized form ahuautle or ahuahutle [a'wautle]) is the roe of an insect called axayácatl, it is obtained by placing some tulle (open fabrics made for this purpose) on the shore of the lakes or formerly leaves of cob or a bundle of grass and/or dry branches tied to a stake. The 8 species of axayácatl are endangered, they are endemic to the Valley of Mexico and their relationship with bedbugs means that they are not very attractive to the common consumer, a fear that is lost when eating it because it is considered a delicacy and even used in gourmet food. Its habitat has been reduced by the desiccation and contamination of aquatic bodies, and the demand, cause its price to be very high. As it happens with many insects, its protein level is higher than that of red meat, with a lower amount of poor-quality fatty acids, and it is an excellent food alternative due to its simple and economical cultivation, which can lead to the conservation of the species..

Some studies have shown that 100 grams of this food (any species) provides 80% protein. Insects contain mineral salts, some are very rich in calcium, contain B vitamins and are an important source of magnesium; In addition, in the larval stage, they provide high-quality calories and are rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids.

Escamoles

Escamoles (from Nahuatl azcatl, "ant", and molli, "stew") are ant larvae that They can be found in the wild in arid or wooded places, depending on the type of ant, although the güijera ant or escamolera (Liometopum apiculatum), predominates. endemic to North America. To find the escamoles, one must carefully discover the nest in which the insects weave a structure of branches and saliva called a trabecula where they deposit their eggs. Then, only two thirds must be removed and covered again with dry nopales and some branches so that the ants can regenerate the extracted eggs and there is no considerable environmental impact. Escamoles have between three and four times more protein than meat and have a delicate flavor that is a challenge to respect in the different means of preparation; therefore, the one who manages to prepare them is considered a good cook.

Maguey Worms

Maguey worms are species of lepidopteran larvae that breed on the leaves of species in the Agave family. The term is actually the popular name for 3 main species:

- Aegiale (Acentrocneme) hesperiaris or white maguey worm.

- Comadia redtenbacheri (before) Hypopta agavis), Chinicuil, chilocuil (from Nahuatl) chilocuilin, "sparkling" or ceiling Or maguey red worm.

- Xyleutes redtenbacheri (Maguey red worm).

The white maguey worm is the larva of a butterfly that grows on the leaves, stalks, and roots of the maguey. It is white (except for the head and extremities), it has a very delicate flavor, which has led it to be one of the most prestigious gastronomic insects in the world. Its preparation methods are various, but it is predominantly fried. It is obtained from the center of the maguey after the rainy season, so the extraction of about 3 or 4 animals (no more are obtained) causes the total loss of the plant; Knowing that the maguey itself takes several years to reach maturity in order to be scraped to obtain the mead with which pulque is obtained; For this reason, they are highly valued ingredients by the Mexican. It is located in the center of the country, but its greatest use is in the state of Hidalgo.

The red maguey worm is a species of ditrisian lepidoptera of the cosidae family, it is a moth larva endemic to North America, where it lives in arid and desert areas; It is consumed as food in central Mexico, mainly in the Mezquital Valley. Chinicuiles are often fried in butter in a clay pot and eaten in tacos or in red sauces. They are also included in mezcal bottles.

Chicatanas

The chicatanas (from Nahuatl tzicatanah "ant with a bag"), in some areas of northern Mexico simply tzicatana, or in Chiapas nucú and bitú (depending on whether it is female and male, respectively), are considered of high value in the kitchen since you have to be very careful when catching them; They are very aggressive and their bites are painful. They have small pincers that, although small, are very strong. During one of the dawns of some seasons, perhaps fleeing the flood of abundant rain, they leave the anthill to be captured by many people who have patiently waited for the right moment, which is difficult to predict because it usually happens in any of the first rains.. The chicatanas ants are a genus of the arrieras ants or leaf-cutter ants.

Its use in the kitchen extended in pre-Columbian times from the southern United States to Colombia and is evident in various dishes; However, in Mexico, the pregnant or queen ant is the one that is given the greatest culinary value, present in dishes from the south, such as Guerrero, Oaxaca, Chiapas, Veracruz, Hidalgo, and Yucatán. Depending on the region, it is cooked roasted, fried, in a snack, in spicy sauce, in tomato sauce, with gourd and seasoned with salt and lemon.

Crawlers

Grasshoppers, popularly known in Mexico as grasshoppers, provide significant amounts of vitamins. Some species have higher proportions of vitamin A than liver and milk and also provide minerals such as zinc, magnesium or calcium. Harvesting these chapulines from cultivated fields, rather than eradicating them through the use of pesticides, not only reduces soil and water contamination, but also provides better quality other food and additional income. They stand out among all for a protein content of up to 77.13%.

Because of its crunchy consistency, similar to that of other fried foods in the country, it is popularly sold as a marinated and roasted snack in markets and street stalls in central and southern Mexico; however, its use is present in more complex dishes, given its relative ease to prepare it with almost any dressing, which makes it a perfect ingredient in stews for tacos and quesadillas.

Jumiles

The jumiles or chumiles (from the Nahuatl xomilli or xotlinilli) also known as mountain bugs, are It consumes them mainly in the states of Morelos (in this state they are consumed especially in Cuautla) and Guerrero (in this state they are consumed especially in Taxco). 11 species are currently known: Edessa conspersa, Edessa cordifera, Edessa montezuma, Edessa mexicana, Edessa petersii, Euschistus egglestoni, Euschistus lineatus, Euschistus strennus, Euschistus (Atizies) taxcoensis, Euschistus sulcacitus, Euschistus sulphutus and Euschistus zopilotensis.

The popularity of jumiles is due to their sale and distribution in street stalls and local markets. They have analgesic and anesthetic properties as a result of the iodine they contain, and can be eaten raw or alive directly, in tacos, in tomato sauce or guacamole. These insects have a characteristic cinnamon flavor coming from the stems and leaves of the oaks on which they feed. In his honor, both in Taxco and in Cerro del Huixteco, both in Guerrero, the festival of the jumil is held, which begins on the first Monday after the Day of the Dead, and concludes in March with the coronation of the Queen of Jumil.

Cymbals

| Mexican dishes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Plates | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Soups and creams |

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Arroz |

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Eggs |

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chiles, vegetables legumes |

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Carne of birds |

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Meat pig |

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Carne of res |

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fish and seafood |

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other meats and insects |

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maíz |

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Trigo |

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Moles and sauces |

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Salads |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Drinks

Alcoholic beverages

Alcoholic beverages that accompany Mexican cuisine can now be drunk almost anywhere in the world. An exception may be pulque, a pre-Hispanic drink whose outlets, the almost extinct "pulquerías", can only be found in Mexico and, in particular, in certain states of the republic. They are popular sites where worship was formerly rendered to Mayahuel (the goddess of pulque).

Mezcal and tequila

The best-known alcoholic beverages inside and outside of Mexico are: mezcal (fermented agave drink) whose aroma and flavor make it unmistakable, and tequila, a national liquor —originally an aperitif— that is drunk in multiple ways, sometimes accompanied by salt and lemon or along with sangrita (spicy drink with orange or tomato juice). Tequila received the denomination of origin on October 13, 1977, date from which the quality of its production increased and consequently increased its international projection. With this denomination of origin, only 181 municipalities among 5 Mexican states: Jalisco, Nayarit, Michoacán, Guanajuato, Hidalgo and Tamaulipas can produce the drink. Mezcal also has a designation of origin, and can only be produced in 9 states of Mexico: Durango, Zacatecas, San Luis Potosí, Tamaulipas, Guanajuato, Michoacán, Guerrero, Puebla and Oaxaca. Thus, in the world, only Tamaulipas, Guanajuato and Michoacán can produce the two drinks. However it may be, these two drinks are highly popular at home and abroad.

Pulque

Pulque (in the Otomi language known as ñogi, in the Purépecha language as urapi, and in Nahuatl as meoctli) is a fermented drink made from mucilage -popularly known in Mexico as mead-, from agave or maguey, especially from maguey pulquero (Agave salmiana) or Agave atrovirens. In addition to being a popular drink in the center of the country for its refreshing flavor, its history is full of mysticism, present in many legends and stories in Mexico. There is a strong pulque and other "cured" ones, that is, pulque to which fruits and syrups (pineapple, strawberry, lemon, orange), seeds (walnut, hazelnut, pine nut) or grains and legumes have been added. (oats, roasted corn, celery, alfalfa, parsley).

Pulque is consumed in pulquerías, very common in urban areas. In the gastronomic aspect, pulque is not only consumed as a drink, there are Mexican dishes that present pulque as an ingredient to create a different seasoning in the dishes. It is the indispensable alcoholic element of the traditional salsa borracha, in addition to being part of the recipes for various types of meats and broths, an example is chicken pulque, which is prepared as fried chicken seasoned in pulque broth and served in casseroles of clay to preserve the flavor.

Sotol

Sotol is a distillate from the sotol plant, cereque or sereque (Dasylirion wheeleri), of the Asparagaceae family, and which grows in the desert of northern Mexico. The plant and the distillate originate from the Sonoran desert and the Chihuahuan desert, a drink that evolved from other drinks from the same plant that the Apaches cultivated. Since 2008 it has a denomination of origin, and can only be produced in the states of Chihuahua, Coahuila and Durango. Its flavor is similar to that of tequila, but stronger despite its very smooth texture.

Pox

Pox is a distillate of Creole corn, endemic to Chiapas, sugar cane, and wheat. Historically it was a panela distillate over old home stills and it was mostly from San Cristóbal de las Casas and San Juan Chamula (Los Altos de Chiapas). Today its production has spread throughout the area.

Tepache

Another typical drink, tepache (from Nahuatl tepiatl), is made from the fermentation of the pineapple peel. The elaboration of the tepache requires four days: in the first two, pieces of pineapple pulp and peel are allowed to rest in a clay pot with cloves and cinnamon, then a mixture of barley and piloncillo, previously boiled, is added. leave to ferment another two days.

Charanda

The charanda is an alcoholic beverage native to the state of Michoacán, obtained by distillation and rectification of fermented musts, prepared from cane juice or its derivatives. The production process is similar to that of rums and other cane spirits. What makes charanda special is the raw material: high altitude cane and farmland, as well as, predominantly, the quality of the water used, although generically it can be considered a kind of rum. It has an exclusive denomination of origin for Michoacán.

Tejuino

The tejuino, tesgüino, or izquiate, known as the delicacy of the Huichol gods, is a light amber-colored drink made from non-fermented corn and sweet cane or piloncillo, denser than light, it is drunk alone or with lemon and salt. It is regularly shaken with a grinder before drinking to raise foam. It is consumed by various ethnic groups from the northwest, northeast, west and central north, and to a lesser extent, from southern Mexico; such as the Yaquis and Pilas of Sonora, the Tarahumaras and Tumbares of Chihuahua, Durango and Jalisco, the Huichols of Jalisco and Nayarit, and the Zapotecs of Oaxaca. Although its sale is typical in states such as Jalisco and Nayarit, while in other places it has a festive value, as is the case of Nochistlán, Zacatecas, where a whole party is held around San Sebastián, the pinole and the tejuino.

Colonchee

The colonche, or nochol, is an alcoholic beverage of pre-Hispanic origin, as old as mezcal (approximately 2000 years) prepared from the fermentation of the pulp of the tuna, fruit of the nopal; more specifically of the red tuna (called cardona). This drink is very popular in the states of San Luis Potosí, Guanajuato and in some areas of Querétaro and Zacatecas. For its preparation, the nopal fruits are peeled and crushed to obtain the juice, which is boiled for 2 to 3 hours. After cooling, the juice is left to ferment for a few days. The color of the colonche is basically red with some bluish tones. Its aroma is fresh, light and its consistency somewhat viscous. Sometimes colonche viejo is added as a fermentation starter, although "tibicos" are also often used. This drink is consumed to a greater extent during the tuna production season, from July to the end of October; although it is a drink in danger of disappearing.

Beer

Mexico beers are well known for their quality, for their soft and delicate flavor, and others for their strong and intense flavor; They are usually taken cold and, on many occasions, accompanied by a lemon. In 2016, the industry reported a production of 105 million hectoliters, which makes the country the fourth largest producer in the world, and the first exporter of beer worldwide (21.3% of the beer exported worldwide), being its main destinations are the United States, Australia and the United Kingdom.

Mexican cuisine and beer turn out to be quite a popular combination in Mexico and other parts of the world, thanks to the fact that beer has a wide range of aromas, flavors, and gastronomic references that make it versatile with many foods. Dark, well-bodied beers with references to chocolate and/or coffee, for example, go with dishes with great personality such as mole poblano. While spicy dishes do so with a beer with woody and fruity aromas that are light and fresh at the same time. Although in the culinary tradition liqueurs and distillates are spoken of as digestives, in the strict sense they can be an irritating digestive burden, which, far from favoring digestion, can worsen it. This is not the case with wine and beer, which, due to their low alcohol content, work as true aperitifs and digestives. Beer is consumed with almost any dish of Mexican cuisine, but it is commonly done in the afternoon, with the main course, or when fish and shellfish are to be consumed.

Wine

Wine production began during the Viceroyalty of New Spain, which brought to America the grape species currently most used for wine production, Vitis vinifera, although it is important to know that it already existed throughout the region the production of beverages by the fermentation of fruits, and 4 endemic North American grape species were widely known. The Mexicas knew the grape as acacholli, the Purépechas knew it as seruráni, the Otomíes called it obxi and the Tarahumaras called it úri. To date, the term that could be used for fermented grapes is disputed, but thanks to this it is not difficult to understand how easy it was for locals to adopt the winemaking tradition.

The early development of wine production and its development through the centuries have made it an extremely important activity for the Mexican economy. The following are distinguished as wine producers: Aguascalientes, Baja California, Baja California Sur, Chihuahua, Coahuila, Guanajuato, Nuevo León, Querétaro and Zacatecas. Mexican wines have been awarded prizes at international festivals, which has caused a strong impact on the foreign market, although due to their high quality, some are perceived by social sectors as high-priced.

Mexican cocktails

A large proportion of the Mexican mixology or cocktails found in bars, clubs or canteens is about a gastronomic rescue of national recipes and ingredients such as tequila or mezcal. Nowadays, restaurants and bars are given the task of preparing or reinventing mixtures that include local or regional distillates or fermented products, soft drinks or Mexican juices, as well as ingredients from Mexican cuisine such as chili and lemon. Also, many of the glasses used are of national invention, as is the case of the ball cup (tongolele or chabela) or variants of the international glasses modified by the Mexican art of blown glass.

Some popular cocktails are:

- Micheladas: while the classic michelada (now "chelada") was a mixture of beer, lemon and salt, served in a "chabela" cup with salt; nowadays it usually includes the three "classic" sauces of the Mexican cocktails (English sauce, seasoning juice and some spicy sauce - usually Tabasco sauce-), as well as juices or ingredients of all kinds such as tamarin.

- Margarita: tequila-based cocktail, triple dry and lemon.

- Clamato prepared or clamato with beer: although the Clamato is a Canadian commercial beverage, in Mexico it has had great popularity for its taste based on tomato, which makes it perfect for cocktails with beer, sauces and/or seafood.

- Blood.

- Vampire: tequila-based drink, bloody, spices and grapefruit soda.

- Black card: Mexican version of the "Cuba Libre" based on tequila.

- Paloma: tequila-based drink, grapefruit soda, lemon and salt.

- Drinks based on Kahlúa: the Kahlúa is a veracruzano liqueur of coffee, very used in bars for drinks like the Black Russian, White Russian, Orgasm, or a flamenco blend of tequila and coffee liqueur called Cucaracha.

- Beverages based on breakup: the breakup is an egg liqueur of populated mixed origin, in the country it is frequently used as digestive or desserts, but also in all kinds of cocktails.

- Crazy pussy

Non-alcoholic beverages

There are also a series of drinks that were devised throughout history, and that round off the universe of Mexican gastronomy, some of them very popular such as atole or the international "drink of the gods": the chocolate.

Fresh waters

Aguas frescas are, without a doubt, the most widely used drinks in Mexican gastronomy during lunch or lunch, although without the need to accompany anything you can get them anywhere in the country, whether in a market, restaurant, mall or park regardless of the time of year. They are made from fruit juice, water and sugar. The most traditional ones can be prepared from sweet fruits (melon, papaya, watermelon, mango, guava, coconut or pineapple), acid fruits (lemon, chia, lime, orange, tamarind, strawberry, cucumber, pitahaya, soursop, changunga, hawthorn, carambola, grapefruit, tangerine or kiwi) or grains, flowers or leaves (hibiscus, horchata, alfalfa or barley). Probably due to their popularity, three of these fresh waters deserve a special mention: horchata water, a drink made from rice, milk and sugar that can be accompanied with cinnamon; Jamaican water, an infusion made from the calyxes (sepals) of the Jamaican rose, very popular throughout the world and which found its special niche as a refreshing drink in Mexico; and chia water, a drink made from water, lemon, sugar and chia (Salvia hispanica), a plant endemic to Mexico and Central America widely cultivated in this region in pre-Hispanic times (in some bibliographies the they mention third in importance only behind corn and beans), once the mixture is made, the water obtains a slight gelatinous consistency and a pleasant and refreshing flavor, in addition to this last drink, Mexicans attribute multiple health benefits.

Chocolate

From Mayan chocolhaa, "hot drink", and Nahuatl xocoatl or cacahuatl, "drink of cacao", most Mesoamerican cultures made chocolate drinks, including the Mayans and Mexicas. The Mexicas rewarded the best warriors of the time by granting them the right to freely consume chocolate. The soldiers were also given species of little balls made with cocoa powder so that they could prepare their chocolate throughout the war. The current drink ultimately resulted from the incorporation of sugar in the 16th century

Currently the drink has variants throughout the territory, although it is usually served as a hot drink during breakfast or dinner. There is a variant between chocolate and atole called champurrado, made with crushed corn dough, dark chocolate and vanilla water, boiled until thick. It is usually served with another typical Mexican dish, tamales.

Atole

From the Nahuatl atolli, "aguado", drink prepared with cooked corn, ground and diluted in water and/or milk and boiled until it has a certain consistency. It is prepared and served in this way, or in its preparation it is mixed with other fruits or ingredients, such as guava, rice, strawberry, pinole, vanilla, cinnamon, piloncillo, among many others. It usually accompanies dishes like tamales. The atole serves as the base for another drink, the chilate.

Keep Yourself

Popularly known as "drink of the gods", it is a drink made from corn and cocoa, traditional from the state of Oaxaca. The main ingredients of tejate are toasted corn flour, fermented cocoa beans, mamey seeds and cocoa flower also known as rosita de cacao, especially common in San Andrés Huayapam, Oaxaca. Its flavor is both fresh and sweet, and it is usually served in jícaras.

Pozol

The pozol or pochotl, (from the Nahuatll pozolli), is a refreshing drink composed of cooked corn dough, cocoa and grains of pochotl or ceiba. It is very popular in the states of Tabasco and Chiapas, as well as in some areas of Veracruz, Oaxaca and Central America. The final consistency is that of a moderately lumpy drink, which tends to settle after a couple of minutes, leaving a residue at the bottom of the container called in the Mayan language "shish" (Hispanicized as "shishito" in Tabasco or "musú" or "motzú" in Chiapas), made up of corn and cocoa dough (or just dough in the case of white pozol). Then, when shaken again, with the characteristic elliptical movement offered by the vessels and gourds in which it is served, called "meneadito del pozol", it resumes its thick consistency and, as it is popularly said "it is an edible drink", alluding to the fact that, at the time of drinking it, the "shish" is chewed, thus quenching thirst and hunger simultaneously. Indeed, pozol can be a drink used especially for food purposes, which is why it is commonly eaten at work sites or in agricultural fields. In the state of Yucatán, a white variant without cocoa is prepared locally called "pozole", which is consumed in various ways: with salt and natural habanero chili (both fresh and sour) or sweetened with sugar and zest of coconut.

Coffee

Mexico is the fifth largest coffee producer in the world, after Brazil, Colombia, Indonesia and Vietnam; is the first producer of organic coffee and one of the main producers of "gourmet" coffee. Café de olla is one of the most common ways to prepare coffee in Mexico. It is made by heating, in water contained in a large, narrow-mouthed clay pot, large and even whole coffee beans, which are mixed appropriately with cinnamon and piloncillo. It is usually consumed a lot in the countryside or in small towns.

Some regions in Veracruz such as Coatepec, Córdoba, Huatusco and Orizaba, the Soconusco region in Chiapas and the Pluma Hidalgo coffee in Oaxaca stand out for the quality of their coffee, although there is also specific mention of the high quality of the grain produced in Colima and Uruapan, Michoacán.

Desserts

- Joy: Sweet made of amaranth of pre-Hispanic origin, sometimes they can take geometric shapes and can be called palanquetas.

- Rice with milk: Dessert derived from rice cooking with condensed and evaporated milks. Add lemon juice or vanilla essence, sprinkle with cinnamon, and add raisins and nuts.

- Ate: Sweet that can be made with multiple varieties of dehydrated fruits such as guava, pear, zapote, pumpkin, tejocote, mango and apple.

- Borrachitos: Sweet invinated milk made of flour and powdered sugar and with a creamy filling of flavors like lemon, pineapple, strawberry, breakope and others.

- Skull of alfeñique: They are skulls made of sugar cane, decorated with sweet with vegetable dyes and papers. They are very representative of the Day of the Dead, when their consumption increases.

- Capirotada: It consists of a toasted bread, cut in slices that are cooked together with pieces of banana, raisins, nuts, guayaba and peanuts, covered with pineapple syrup and grated table cheese.

- Chichimbré: Sweet bread, which is made from corn or wheat flour, piloncillo, cinnamon, vanilla and yeast.

- Chocolate with churros

- Chocolate tablet: Panel made of triangular pieces of chocolate. It is also used in mill making, pot coffee, hot chocolate, atoles and cakes.

- Chongos zamoranos: Dessert of curdled milk and egg, sugar, cinnamon and some spices, which forms soft and gelatinous pieces of sweet flavor and smooth and juicy consistency.

- Cocada: Made from a coconut and milk mass that is later baked.

- Corico:Corico is a traditional corn cookie from the Mexican state of Sinaloa.