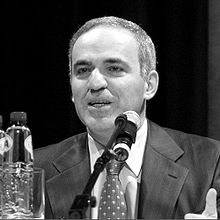

Garry Kasparov

Garry Kimovich Kasparov (Russian: Гарри Кимович Каспаров, AFI: [ˈgarʲɪ ˈkʲiməvʲɪtɕ kɐˈsparəf]; Baku, Azerbaijan SSR, Soviet Union, today Azerbaijan, April 13, 1963) is a Russian chess Grandmaster, politician and writer, who obtained Croatian citizenship in 2014. He was World Chess Champion from 1985 to 1993, and World Champion PCA version from 1993 to 2000. He is considered one of the greatest players of all time.

Kasparov became the youngest World Champion in history in 1985. He held the official World Chess Federation (FIDE) title until 1993, when a dispute with the Federation led him to create a rival organization, the Professional Chess Association. He continued to hold the World Classical Chess Championship, until his defeat by Vladimir Kramnik in 2000.

Kasparov has topped the FIDE world rankings almost continuously from 1986 until his retirement in 2005, reaching a score of 2851 in July 1999, the highest ever achieved by GM Magnus Carlsen in April 2014, al reach this 2882 Elo points. He has also won the Chess Oscar eleven times. He is also known for his confrontations with computers and chess programs, especially after his loss in 1997 against Deep Blue ; this was the first time a computer had defeated a World Champion in a tournament-paced match.

Kasparov announced his retirement from professional chess on March 10, 2005 to devote his time to politics and writing on chess topics. He formed the United Civic Front movement and joined as a member of The Other Russia, a coalition opposing the Vladimir Putin administration.

On September 28, 2007, Kasparov entered the Russian presidential race, receiving 379 of 498 votes at a congress held in Moscow for The Other Russia. Although his party ultimately did not contest the March 2008 elections, due, according to Kasparov himself, to the impossibility of obtaining a venue large enough to house the number of supporters legally required to support his candidacy. Kasparov blamed "official obstruction" due to lack of available space.

Kasparov was awarded the United Nations UN Watch prize for his peaceful struggle for respect for fundamental freedoms in Russia. He is currently President of the Human Rights Foundation and chairs its International Council.

Biography

Early career

Garri Kímovich Veinshtéin was born in Baku (Azerbaijan) to an Armenian mother Clara Shaguénovna Kasparian and a Russian Jewish father Kim Moiséyevich Veinshtéin. His beginnings in chess were watching his father, who taught him the basics; but he began to study chess seriously after his parents gave him a chess problem. His father died when he was seven years old. He adopted his mother's Armenian surname, Kasparian, modifying it to a more Russified version, Kasparov.

From the age of seven, Kasparov attended the Palace of Pioneers and at ten began studying at Mikhail Botvinnik's chess school with the notable master Vladimir Makogonov. Makogonov helped develop Kasparov's positional skills and taught him to play the Caro-Kann Defense and the Tartakówer System of the Queen's Gambit. Kasparov won the USSR Junior Championship in Tbilisi in 1976, with 7 points out of 9, to the age of thirteen. He repeated the feat the following year, winning with 8.5 out of 9. He was trained by Aleksandr Sakharov during this time.

In 1978, Kasparov participated in the Sokolsky Memorial in Minsk. He had been invited as an exception but finished in first place and became a teacher. Kasparov has repeatedly said that this tournament was a turning point in his life and that it convinced him to choose chess as his career. "I will remember the Sokolski Memorial for as long as I live," he wrote. He also said that after the victory, he thought he had a chance at the World Championship.

He first qualified for the USSR Chess Championship at the age of 15 in 1978, the youngest player at that level. He won the 64-player Swiss tournament in Daugavpils on tie-break with Igor Vasilievich Ivanov, to capture the only qualifying place.

Kasparov quickly rose up the FIDE rankings. Due to an oversight of the Soviet Union Chess Federation, he participated in a Grandmaster tournament in Banja Luka (Yugoslavia) in 1979 when he had not qualified as a Master (the Federation thought it was a junior tournament). He won this high-class tournament, emerging with a provisional ranking of 2595, enough to catapult him into the elite group of chess players (at the time, world number 3, former champion Boris Spassky had 2630, while world champion Anatoli Karpov had 2690). The following year, 1980, he won the World Youth Chess Championship in Dortmund, West Germany. After that year, he appeared in the senior category as second substitute for the Soviet Union team at the Chess Olympiad in Valletta (Malta) and became an International Grandmaster.

Towards the Summit

As a teenager, Kasparov twice tied for first place in the USSR Chess Championship, in 1980-81 and 1981-82. His first victory at the international superclass level was in Bugojno 1982. He got a place in the 1982 Moscow Interzonal Tournament, which he won, qualifying for the Candidates Tournament. At nineteen years of age, he was the youngest Candidate since Bobby Fischer, who was fifteen when he qualified in 1958. At this time, he was already the second-ranked player in the world, trailing only the world chess champion. Anatoli Karpov on the January 1983 list.

Kasparov's first Candidates match (quarter-final) was against Aleksandr Beliavsky, whom Kasparov defeated 6-3 (+4 =4 -1). Politicians feared Kasparov's semi-final against Viktor Korchnoi, who It was scheduled to be played in Pasadena (California). Korchnoi had defected from the Soviet Union in 1976 and was at the time the strongest active non-Soviet player. Various political maneuvers prevented Kasparov from playing with Korchnoi and Kasparov resigned from the match. This was resolved by Korchnói allowing the match to be played again in London, along with Vasili Smyslov's match against Zoltan Ribli. Kasparov lost the first game but won the match 7-4 (+4 =6 -1).

In 1984, he won the Candidates final 8.5-5.5 (+4 =9 -0) against resurgent former world champion Vasili Smyslov in Vilnius, thus qualifying to play Anatoli Karpov for the World Championship. In that year he joined the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and was elected to the Komsomol Central Committee.

1984 World Championship

The 1984 World Championship match between Anatoly Karpov and Garri Kasparov had many ups and downs and a controversial ending. Karpov started in good form and after nine games Kasparov was down 4-0 in a match to his first six wins.

But Kasparov achieved 17 consecutive draws. He lost game 27 and then returned to the fight with another series of draws until game 32, his first win against the World champion. He continued a succession of 15 draws, until game 46; the previous record length for a world title was 34 games, José Capablanca's match against Alexander Alekhine in 1927.

At this point Karpov, twelve years older than Kasparov, was close to exhaustion and did not look like the player who started the match. Kasparov won games 47 and 48 to make it 5-3 in favor of Karpov. Then, the match was ended without a result by Florencio Campomanes, the FIDE president and a new match was announced a few months later.

The termination was controversial, as both players stated that they preferred the match to continue. When he announced his decision at a press conference, Campomanes cited the health of the players, who had been tense for the duration of the match. Karpov had lost 10 kilos and was hospitalized several times.[citation needed] But Kasparov was in excellent health and extremely offended by Campomanes' decision, asking him why was closing the match if both players wanted to continue. It seemed that Kasparov, who had won the last two games before the suspension, felt that he would win despite his 5-3 deficit. He seemed to be physically stronger than his opposite of him and in subsequent games he had played better chess.

The match would ultimately be the first and only world championship match to be abandoned without a result. Kasparov's relations with Campomanes and FIDE soured greatly and the feud between them finally came to a head in 1993 with Kasparov's break from FIDE.

World Champion

The second Karpov-Kasparov match in 1985 was staged in Moscow as a best of 24 game where the first player to reach 12.5 would claim the title. The results of the previous match would not be retained. In the event of a 12-point tie, Kárpov would retain the title; and if Kasparov was the winner, Karpov would have the right to rematch the following year. Kasparov secured the title at the age of 22 years, 6 months and 27 days by a score of 13-11. This broke the record for the youngest World Champion, held for twenty years by Mikhail Tal, who was twenty-three when he defeated Mikhail Botvinnik in 1960. Kasparov's victory with the black pieces in game 16 has been recognized as one of the all-time masterpieces in chess history.

The rematch match took place in 1986, in London and St. Petersburg, with 12 games played in each city. At one point in the match, Kasparov opened up a three-point gap and seemed determined on his way to a decisive matchup victory. But Karpov got into the fray winning three straight games to level the score. At this time, Kasparov fired one of his coaches, Grandmaster Yevgeny Vladimirov, accusing him of selling his opening preparation to Karpov's team (as he described in Kasparov's autobiography Limitless Challenge ). Kasparov won another game to keep his title by a final score of 12.5-11.5.

Once again both players met for the 1987 world championship played in Seville, since Kárpov had qualified in the candidate matches to become the official challenger. It was the first time that two Soviet players played in a complete World Cup outside the USSR. This duel was very disputed, without conceding more than a point advantage by any player at any time. Kasparov was down a point in the final game, needing a win to keep his title. A long and tense game resulted, with Karpov dropping a pawn just before the first time control and Kasparov eventually winning a lengthy endgame. Kasparov retained the title from him as the match ended in a tie with a score of 12-12. All this means that Kasparov had played Karpov four times in the period 1984-1987, an unprecedented statistic in chess. Matches organized by FIDE had taken place every three years since 1948, and only Mikhail Botvinnik exercised his right to rematch before Karpov.

Kasparov demonstrated his media savvy by appearing in an interview in the American magazine Playboy, which was published in November 1989.

A fifth meeting between Kasparov and Karpov was held in New York and Lyon (France) in 1990, with 12 games in each city. Again, the result was close, with Kasparov winning 12.5-11.5.

Break with FIDE

With the title of World Champion in hand, Kasparov began to battle against FIDE, as Bobby Fischer had done twenty years before but this time from within FIDE. Starting in 1986, he created the Grandmasters Association (GMA), an organization that represents chess players and gave them more than FIDE activities. Kasparov assumed a leadership role. The GMA's crowning achievement was organizing a series of six World Cup tournaments for elite players. There was a sometimes difficult relationship with FIDE and a kind of truce was brokered by Bessel Kok, a Dutch businessman.

This truce lasted until 1993, by which time a new challenger had qualified through a FIDE candidate cycle for Kasparov's next defense: Nigel Short, a British International Grandmaster who had defeated Karpov in the semifinals of the 1992 candidate cycle, and then Jan Timman in the final. After a confusing and condensed bidding process resulted in less funding than expected (Nigel Short: Quest for the Crown, by Cathy Forbes), the world champion and his challenger decided to play out of the jurisdiction of FIDE, under another organization created by Kasparov called the Professional Chess Association (PCA).

In a 2007 interview, Kasparov would say that the break with FIDE was the worst mistake of his career, as it hurt chess for a long time.

Kasparov and Short were expelled from FIDE and played their well-sponsored match in London. Kasparov won convincingly by 12½-7½. The game significantly increased interest in chess in the UK, with an unprecedented level of coverage on Channel 4. Meanwhile, FIDE organized a World Championship match between the semi-finalists eliminated from the candidate cycle: Jan Timman and former world champion Kárpov, who won 12½-8½.

After these matches, Karpov was proclaimed the FIDE world champion, while Kasparov, PCA champion, claimed for himself the title of Classical Chess world champion, on the tradition that only the world champion is the one who Defeat the reigning champion. Thus began a world chess title schism that lasted 13 years.

Kasparov defended his title in 1995 in a match against Indian superstar Viswanathan Anand at the World Trade Center in New York. Kasparov won the match 4 wins to 1 with 13 draws. It was the last World Championship to be contested under the auspices of the PCA, which collapsed when Intel, one of its biggest supporters, ended its sponsorship.

Kasparov tried to organize another match for the World Championship, under another organization, the World Chess Association (WCA) together with the organizer of the Ciudad de Linares International Chess Tournament Luis Rentero. Alekséi Shírov and Vladimir Krámnik played in Cazorla (Jaén, Spain) a meeting of candidates to decide the challenger, which Shírov won against all odds. But when Rentero admitted that the required and promised funds had never materialized, the WCA went under.

This left Kasparov stranded, but yet another BrainGames.com-based organization appeared, headed by Raymond Keene. No match was held against Shírov and talks with Anand failed, so a match was held against Kramnik.

Loss of title

The Kasparov-Kramnik match took place in London in the second half of 2000. Kramnik had been a student of Kasparov at the legendary Botvinnik/Kasparov chess school in Russia and had worked on Kasparov's team during the 1995 match against Viswanathan Anand.

The best-prepared Kramnik won Game 2 against Kasparov's Grünfeld Defense and took winning positions in Games 4 and 6. Kasparov made a decisive mistake in Game 10 with the Nimzo-Indian Defense, which Kramnik exploited to win in 25 moves. With White, Kasparov could not break the passive but solid Berlin Defense of the Spanish Opening and Kramnik satisfactorily drew all his games with Black. Kramnik won the match 8.5-6.5 and for the first time in fifteen years Kasparov had no world title. He became the first player to lose a world championship title without winning a game since Emanuel Lasker's loss to José Raúl Capablanca in 1921.

After the title loss, Kasparov went on to string together several major tournament victories and remained the highest-ranked player in the world, ahead of both world champions. In 2001 he declined the invitation to the 2002 Dortmund Candidates Tournament for the classic title, claiming that his results granted him a rematch against Kramnik.

Due to these great results and his status as world number 1 in much of the public opinion, Kasparov was included in the so-called "Prague Agreement", planned by Yasser Seirawan which was trying to reunify the two World Champion titles. Kasparov was due to play a match against FIDE World Champion Ruslan Ponomariov in September 2003, but he was suspended after Ponomariov refused to sign his contract. Instead, he had planned a meeting with Rustam Kasimdzhanov, winner of the 2004 FIDE World Championship, which was to be held in January 2005 in the United Arab Emirates. This too failed due to lack of funds. Plans to celebrate the game in Turkey came too late. Kasparov announced in January 2005 that he was tired of waiting for FIDE to organize his match and decided to stop all his efforts to win back the World Champion title.

Retirement from chess

After winning the prestigious Ciudad de Linares International Chess Tournament for the ninth time, Kasparov announced on March 10, 2005 that he would retire from competitive chess. He cited the lack of personal goals in the chess world as the reason (he commented when he won the Russian Chess Championship in 2004 that it had been the last major title he had never won) and expressed his frustration at the failure of reunification. of the world title.

Kasparov said he could play some rapid tournaments for fun, but he would try to spend his time on his books, including the My Great Forerunners series and a job straddling decision-making at chess and other areas of his life and would continue to be involved in Russian politics, which he sees as "headed astray."

Kasparov has been married three times: to Masha Arapova, with whom he had a daughter before divorcing; with Yulia Vovk, with whom he had a son before his divorce in 2005 and with Daria Tarásova, with whom he also had a son.

Chess after retirement

On August 22, 2006, in his first public game since his retirement, Kasparov played in the Lichthof Chess Tournament, a blitz tournament played at 5 minute plus 3 second increments per move. Kasparov tied for first place with Anatoli Kárpov, with 4.5/6.

Between September 21-25, 2009, Kasparov played Karpov again, this time in an exhibition match in the Spanish city of Valencia played in 12 games (8 rapid and 4 blitz). Kasparov won by 9 points to 3.

In July 2021, Kasparov participates in the Grand Chess Tour of Croatia in blitz mode. The chess player from Baku was last in his group with a result of eight defeats and a draw.

Politics

Kasparov's political involvement began in the 1980s. He joined the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1984 and in 1987 was elected to the Komsomol Central Committee. But in 1990 he left the party and in May he took part in the creation of the Democratic Party of Russia. In June 1993, he became involved in the creation of the party bloc & # 34; Election of Russia & # 34; and in 1996 he was part of Boris Yeltsin's election campaign. In 2001 he expressed his support for the Russian television NTV.

After his retirement from chess in 2005, Kasparov turned to politics, creating the Civic United Front, a social movement whose main goal is to "work to preserve electoral democracy in Russia." He has sworn to "restore democracy" in Russia by overthrowing Russian President Vladimir Putin, of whom he is an outspoken critic.

Kasparov was part of the establishment of The Other Russia, a coalition that included Kasparov's United Civic Front and various nationalist and even far-right parties, such as Eduard Limonov's outlawed National Bolshevik Party, the Russian Republican Party of Vladimir Ryzhkov and other organizations.

On April 10, 2005, Kasparov was in Moscow at a promotional event when he was hit on the head with a chessboard he had just signed. It was claimed that the assailant had told him "I loved you for your chess, but your political ideals are wrong" immediately before the attack. Kasparov has been the subject of other similar episodes.

Kasparov helped organize the St. Petersburg March of Dissent on March 3, 2007 and the March 24, 2007 March, both involving several thousand people rallying against Putin and the policies of St. Petersburg Governor Valentina Matviyenko. On April 14, he was briefly arrested by Moscow police while leading a demonstration. He was detained for about 10 hours and released.

He was cited by the FSB for being suspected of violating Russian anti-extremism laws. This law was previously applied for the conviction of Boris Stomajin.

Speaking about Kasparov, former KGB general Oleg Kalugin has remarked: "I don't talk about the details of the people who are now known to be all dead because they were publicly loud. I am quiet, but currently there is only one man who is loud and may be in trouble: the world chess champion Kasparov. He has been very outspoken in his attacks on Putin and I think he will probably be next on the list."

In 1991, Kasparov received the Keeper of the Flame award from the Center for Security Policy (an American think tank), for anti-communist resistance and propagation of democracy. Kasparov was an exceptional recipient as the award is given to "individuals who dedicate their public careers to upholding the values of the United States around the world".

In April 2007, Kasparov was appointed to the board of directors of the National Security Advisory Council of the Center for Security Policy, a non-profit, apolitical, national security organization that specializes in identify necessary policies, actions, and resources that are vital to US security'. Kasparov confirmed this, adding that he was fired shortly after receiving the award. He noted that they did not know his affiliations and suggested that he was accidentally included on the board because he received the 1991 Conservative of the Flame award from this organization. But Kasparov maintained his association with the neoconservative leadership by giving speeches at think tanks like those of the Hoover Institute.

In October 2007, Kasparov announced his intention to run for the Russian presidency as the candidate of the Other Russia coalition and vowed to fight for a "just and democratic Russia. After that month, he traveled to the United States appearing on the television shows of Stephen Colbert, Wolf Blitzer, Bill Maher and Chris Matthews.

On November 24, 2007, Kasparov and other Putin critics were detained by Russian police at an Other Russia rally in Moscow. This was after an attempt by protesters to march against the electoral commission, which had blocked the Other Russia candidates from the parliamentary elections. He was subsequently sentenced to five days' imprisonment and released. from prison on November 29.

On December 12, 2007, Kasparov announced that he had withdrawn his presidential candidacy due to the impossibility of renting a meeting room where at least 500 of his supporters could hold an assembly to approve his candidacy, as is legally required. When the term expired on that date, it was impossible for him to continue in the electoral race. Kasparov's spokeswoman accused the government of using the crackdown to discourage everyone from renting a hall for the meeting, saying the election commission had rejected a proposal that the meeting be held in separate smaller venues at the same time instead of in a single room.

In March 2010, Kasparov signed the Russian opposition's open letter 'Putin must go', being one of the main authors of this political campaign.

On August 20, 2012, Kasparov was arrested while protesting outside the Pussy Riot trial in Moscow on the pretext of biting a police officer. The arrest caused consternation in several human rights organizations and some countries in the West. Kasparov was finally released hours later and on August 25 he was found not guilty of the charges for which he was arrested.

Since June 2013, Garri Kasparov has not returned to Russia, he spends every summer in Makarska, near Split, and understands Croatian well, so he applied for citizenship in Croatia (a country belonging to the European Union), which he obtained in 2014.

In 2015, Kasparov published his book Winter Is Coming: Why Vladimir Putin and the Enemies of the Free World Must Be Stopped. Kasparov continues to criticize Putin's government and to be active in the political sphere.

Kasparov supports recognition of the Armenian genocide.

In 2022, he criticized the PCE seal of 2022 for considering it a shame, and wondering on Twitter if the next thing would be to "put a swastika on it".

Achievements in chess rankings

Kasparov's records in elite chess are:

- Kaspárov maintains the record of being number 1 in the world for the longest period.

- Kaspárov had the largest ELO in the world continuously from 1986 to 2005. The only exception is that Vladimir Krámnik equaled him in January 1996. He was briefly expelled from the list after his break with the FIDE in 1993, but during that time he led the list of the rival PCA. At the time of its withdrawal, it remained number 1 in the world, with a score of 2812. Its classification has fallen to the list of inactives since January 2006.

- According to the alternative calculations of Chessmetrics, Kaspárov was the world's most scored player continuously from February 1985 to October 2004. It also maintains the highest average score of all time in a period of 2 (2877) to 20 (2856) years and is second behind Bobby Fischer (2881 vs 2879) in a period of one year.

- In January 1990, Kaspárov managed to overcome the 2800-point barrier, breaking Bobby Fischer's old 2785-point record. On the July 1999 list of the FIDE Kaspárov reached the record of 2851 points of ELO, the highest score never achieved until the Norwegian Magnus Carlsen beats it in 2012 to impose a new record of 2872 in February 2013.

Olympics and other major team tournaments

Kasparov played a total of eight chess Olympiads. He represented the USSR four times and Russia four times after the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991. In his Olympic debut in 1980, he became the youngest player to represent either the Soviet Union or Russia at the age of 17. at that level, a record that was broken by Vladimir Kramnik in 1992. In 82 games, he has scored (+50 =29 -3), with 78.7% and won a total of 19 medals, including the gold medal in all eight competitions he played. At the 1994 Moscow Olympics, he played a significant organizational role, helping to launch the event shortly after Thessaloniki canceled its host bid just weeks before the scheduled dates.

Kasparov's detailed records at the Olympics are:

- The Valet (1980), 2nd reserve of the USSR, 9.5/12 (+8 =3 -1), gold by equipment, bronze by boards.

- Lucerne (1982), 2.o board of the USSR, 8.5/11 (+6 =5 -0), gold by equipment, bronze by boards.

- Dubai (1986), 1.♪ board of the USSR, 8.5/11 (+7 =3 -1), gold by equipment, gold by boards, gold by performance.

- Thessaloniki (1988), 1.♪ board of the USSR, 8.5/10 (+7 =3 -0), gold by equipment, gold by boards, gold by performance.

- Manila (1992), 1.♪ Russian board, 8.5/10 (+7 =3 -0), gold by equipment, gold by board, silver by performance.

- Moscow (1994), 1.♪ Russian board, 6.5/10 (+4 =5 -1), gold by equipment.

- Yerevan (1996), 1.♪ Russian board, 7/9 (+5 =4 -0), gold by equipment, gold by boards, silver by performance.

- Bled (2002), 1.♪ Russia board, 7.5/9 (+6 =3 -0), gold by equipment, gold by boards.

Kasparov made his international debut for the USSR at the age of 16 at the 1980 European Team Chess Championship and played for Russia in 1992. He won a total of five medals. The detailed results of it are:

- Skara (1980), 2nd reserve of the USSR, 5.5/6 (+5 = 1 -0), gold by equipment, gold by boards.

- Debrecen (1992), 1.♪ Russian board, 6/8 (+4 =4 -0), gold by equipment, gold by board, silver by performance.

Kasparov also represented the USSR once at the Youth Olympiad, but detailed data is incomplete on:

- Graz (1981), Table 1 of the USSR, 9/10 (+8 =2 -0), gold by equipment.

Other records

Kasparov holds the record for most consecutive professional tournament wins, finishing first or tied for first in 15 individual tournaments from 1981 to 1990. The streak was snapped by Vasili Ivanchuk at Linares in 1991, where Kasparov finished 2nd. º, half a point below him. The details of his record are:

- Biskek (1981), USSR Championship, 12.5/17, 1.o empatado.

- Bugojno (1982), 9.5/13, 1.o.

- Moscow (1982), Interzonal, 10/13, 1.o.

- Nikšić (1983), 11/14, 1.o.

- Brussels OHRA (1986), 7.5/10, 1.o.

- Brussels (1987), 8.5/11, 1.o empatado.

- Amsterdam Optiebeurs (1988), 9/12, 1.o.

- Belfort (Copa del Mundo) (1988), 11.5/15, 1.o.

- Moscow (1988), USSR Championship, 11.5/17, 1.o empatado.

- Reikiavik (1988), 11/17, 1.o.

- Barcelona (Copa del Mundo) (1989), 11/16, 1.o empatado.

- Skelleftea (Copa del Mundo) (1989), 9.5/15, 1.o empatado.

- Tilburg (1989), 12/14, 1.o.

- Belgrade (Investbank) (1989), 9.5/11, 1.o.

- Linares (1990), 8/11, 1.o.

In addition to his results, Kasparov has won the Chess Oscar 11 times, being the biggest winner of this award. He has also held first place in the FIDE world rankings on 23 occasions.

Books and other writings

Kasparov has written several chess books. He published a somewhat controversial autobiography when he was just 20 years old. Originally titled Son of Change, it was later renamed Reto Sin Límites (Desafío Sin Límites in the Spanish edition, Ediciones Cúbicas, 1990). This book was subsequently updated several times after he became a World Champion. Its content is mainly literary, with a small chess component in terms of uncommented games. He published a collection of annotated games in the 1980s: Gari Kasparov: Life, Games, Career and this book has also been updated several times in subsequent editions. He commented on his own games intensively for the Chess Informant Yugoslav series and for other chess publications. In 1982, he co-authored Batsford Chess Openings with British Grandmaster Raymond Keene and this book was a huge bestseller. It was updated into a second edition in 1989. He also co-authored two opening books with his coach Aleksandr Nikitin in the 1980s for the British publication Batsford, on the Classical Variations of the Caro-Kann Defense and on the Scheveningen Variation of the Defense. Sicilian. Kasparov has also contributed extensively to the five-volume opening series Encyclopedia of Chess Openings.

In 2007, he wrote How Life Imitates Chess, an examination of the parallels between decision-making in chess and the world of business. In 2008 Kasparov published a comprehensive obituary for Bobby Fischer:

They often ask me if I have met or faced Bobby Fischer. The answer is no, I never had that chance. But even though he saw me as a member of the evil chess organization that he felt had stolen and deceived him, I'm sorry I never had the opportunity to thank him personally for what he did for our sport.

He is a senior advisor to Everyman Chess Book Publishing.

My Great Predecessors Series

In 2003, the first of his five-volume work Gari Kasparov in My Great Predecessors was published. Dealing with world champions Wilhelm Steinitz, Emanuel Lasker, José Raúl Capablanca and Alexander Alekhine and some of their strong contemporaries, this volume has received high praise from some critics (including Nigel Short), though it was criticized by others for historical inaccuracies. and analysis of games copied directly from unattributed sources. Through suggestions on the book's website, many of these defects were corrected in subsequent editions and translations. Despite this, the first volume won the British Chess Federation Book of the Year Award in 2003. Volume two, covering Max Euwe, Mikhail Botvinnik, Vasili Smyslov and Mikhail Tal, appeared in late 2003. volume three, covering Tigrán Petrosyan and Boris Spaski, appeared in early 2004. In December 2004, Kasparov released volume four, covering Samuel Reshevsky, Miguel Najdorf and Bent Larsen (none of these were World Champions), but it was mainly focused on Bobby Fischer. The fifth volume was dedicated to the chess careers of the World Champion Anatoli Kárpov and his challenger Víktor Korchnói and was published in March 2006.

Modern Chess Series

After the publication of the series My Great Predecessors, Garri Kasparov started a new series entitled On Modern Chess, which will consist of five books. The first book in this series is entitled Revolution in the 70s (published in March 2007) and is dedicated to highlighting the great importance of opening preparation in the new era pioneered by Fischer and Karpov. The second book in the series is titled Kasparov vs Karpov 1975-1985 (published in September 2008) and covers extensively the world championship matches held in 1984 and 1985, analyzing the games in depth., as well as giving his vision on the non-chess aspects that surrounded the match.

Kasparov against computers

Deep Thought, 1989

Kasparov easily defeated the Deep Thought computer 2-0 in a two-game match in 1989 (Hsu, 2002, pp. 105-16).

Deep Blue, 1996

In February 1996, in Philadelphia, the IBM chess computer Deep Blue defeated Kasparov in a game using conventional time controls, in the first game of the match. But Kasparov recovered well, posting three wins and two draws to easily win the match. Kasparov had demonstrated a control of strategy far beyond the crushing brute-force tactics of the machine. Deep Blue could calculate 200 million positions per second, but lacked the sensitivity to grasp the subtlety of positional play, the hallmark of true mastery.

Deeper Blue, 1997

In May 1997, an updated version of Deep Blue known unofficially as "Deeper Blue", defeated Kasparov 3½-2½ in a well publicized six-way match. games. The match was tied after five games, but Kasparov was beaten in Game 6. This was the first time a computer had beaten the world champion in competition. A documentary was made about this famous encounter entitled Game Over: Kasparov and the Machine. However, it should be noted that in game 6, Kasparov made a blunder early in the game. Kasparov cites exhaustion and discontent with the behavior of the IBM team as the main reason.

Kasparov claimed that several factors had weighed against him in this encounter. In particular, he was denied access to recent Deep Blue games, in contrast to the computer team that could study hundreds of Kasparov's games.

After the loss, Kasparov said he sometimes saw deep intelligence and creativity in the machine's movements, suggesting that during the second game, human players intervened, contravening the rules. IBM denied that they were cheating, saying that the only human intervention occurred between games. The rules provided by the developers to modify the program between games, an option they said they used to shore up weaknesses in the computer game that appeared during the course of the game. Kasparov requested copies of the machine's logs, but IBM denied them, although the company later posted the logs on the Internet. Kasparov requested a rematch, but IBM refused and retired Deep Blue.

Kasparov maintains that he had been told the match was going to be a scientific project, but it was soon discovered that IBM only wanted to defeat him.

Deep Junior, 2003

In January 2003, he participated in a six-game match with classical time controls for a million dollar prize that was dubbed by FIDE the "Men's World Championship. vs. Machine", against Deep Junior. The computer engine evaluated three million positions per second. After one victory each and three draws, everything was left for the final game. The final game of the match was televised on ESPN2 and was viewed by an estimated 200-300 million people. After reaching a decent position Kasparov offered a draw, which was soon accepted by the Deep Junior team. When asked about the offer of a draw, Kasparov said that he was afraid of making a big mistake.Originally it was planned as an annual tournament, but the meeting was not repeated.

X3D Fritz, 2003

In November 2003, he played a four-game game against the computer program X3D Fritz (said to have an estimated ELO rating of 2807), using a virtual board, 3D glasses, and a speech recognition system. After two draws and one win each, the X3D Man Machine match ended in a draw. Kasparov was paid $175,000 for the result and took home a gold trophy. Kasparov continued to lament the fatal mistake in game two that cost him a crucial point. He felt that he had outplayed the machine and played well. "I just made a mistake but unfortunately that mistake made me lose the game".

International Chess Federation in 2014

The president of the International Chess Federation since 1995 is the Russian millionaire Kirsán Iliumzhinov. Gari Kasparov is presented as a candidate for the presidency of FIDE, for which he began a campaign in the 178 member countries of FIDE, the elections were held on August 11, 2014. The Russian Kirsán Iliumzhinov, who has been in the FIDE for many years position, he was declared the winner by 110 votes to 61, in an election held on the sidelines of the 2014 Chess Olympiad in Norway. The news caused discontent among many chess fans. After the result was announced, Kasparov declared that it was a very sad day for him, in addition to spreading via Twitter that he and his team would never stop working for the good of chess.

Other data

- in 1993, he was advisor and manmark of chess videogame Kasparov's Gambit of Electronic Arts.

- has been recognized as the inventor of advanced Chess in 1998, a new form of chess in which a human and a computer play together.

- has two European patents: EP1112765A4: METHOD TO JUGATE A THING AND SYSTEM TO REALIZE 1998 and EP0871132A1: METHOD OF JUGAR TO A THING OF LOTERY AND SYSTEM ADOPTED 1995

- is a follower of the New Chronology of Anatoli Fomenko.

- coauthor of the game design Kasparov Chesmate, a chess computer program.

- is chairman of the International Council of the New York-based Human Rights Foundation.

- won the daily prize Brand brand Marca Leyenda in 1997.

Books

- The Test of Time (Russian Chess) (1986, Pergamon Pr)

- Match for the World Chess Championship: Moscow, 1985 (1986, Everyman Chess)

- Change child: an autobiography (1987, Hutchinson)

- London-Lening Championship Parts (1987, Everyman Chess)

- Unlimited challenge (1990, Grove Pr)

- Challenge without limits (1990, Civic Editions) - Spanish edition.

- Sicily Scheveningen (1991, B.T. Batsford Ltd)

- Lady's Indian Defense: Kaspárov System (1991, B.T. Batsford Ltd)

- Kaspárov v. Kárpov, 1990 (1991, Everyman Chess)

- Kaspárov on the Indian king (1993, B.T. Batsford Ltd)

- The chess challenge of Garry Kaspárov (1996, Everyman Chess)

- Chess lessons (1997, Everyman Chess)

- Kasparov Against the World: The Story of the Greatest Online Challenge (2000, Kasparov Chess Online)

- My great predecessors, part I (2003, Everyman Chess)

- My great predecessors, Part II (2003, Everyman Chess)

- Check it out!: My first chess book (2004, Everyman Mindsports)

- My great predecessors, part III (2004, Everyman Chess)

- My great predecessors, Part IV (2004, Everyman Chess)

- My great predecessors, part V (2006, Everyman Chess)

- How life imitates chess (2007, William Heinemann Ltd.)

- Garry Kaspárov in modern chess, part 1: Revolution in the 1970s(2007, Everyman Chess)

- Garry Kaspárov in modern chess, part 2, Kaspárov against Kárpov 1975–1985(2008, Everyman Chess)

- Garry Kaspárov in modern chess, part 3, Kaspárov against Kárpov 1986–1987(2009, Everyman Chess)

- Garry Kaspárov in modern chess, part 4, Kaspárov against Kárpov 1988–2009(2010, Everyman Chess)

- Garry Kaspárov against Garry Kaspárov part 1 (2011, Everyman Chess)

- The Blueprint: Reviving Innovation, Rediscovering Risk, and Rescuing the Free Market (2013, W. W. Norton & Co)

Contenido relacionado

Andres Nin

Diego Rodriguez (mathematician)

Santiago de Chile