Ganymede (mythology)

In Greek mythology, Ganymede (Greek Γανυμήδης Ganymêdês) was a divine hero from the Troads. Being a handsome Trojan prince, he was kidnapped by the god Zeus, who made him his lover and cupbearer to the gods.

Etymology

Regarding the etymology of his name, Robert Graves proposes the following in Greek myths: ganuesthai + medea ("rejoicing in virility »).

Myth

Family

Ganymede was the son of King Tros, who gave his name to Troy (or Laomedon, according to some versions), and a descendant of Dardanus; his mother was Callirroe, daughter of Scamander. His brothers were Ilo and Asáraco. The latter was the great-grandfather of Aeneas.

The Kidnapping of Ganymede

Ganymede was kidnapped by Zeus on Mount Ida, in Phrygia (which currently corresponds to Turkey), the place of more than one legend about the mythical history of Troy. Ganymede spent there the time of exile that many heroes underwent in their youth, tending a flock of sheep or, alternatively, the rustic or chthonic part of his upbringing, together with his friends and tutors. Zeus saw him, fell in love with him almost instantly, and sending an eagle or transforming himself into one took him to Mount Olympus.

Ascent to Olympus

On Olympus, Zeus made Ganymede his lover, bedfellow, and cupbearer to the gods, supplanting Hebe. All the gods were filled with joy to see the beauty of the young man, except Hera, the wife of Zeus, who treated him with contempt. His hatred for the boy was used by mythographers to justify his grudge against the Trojans (along with the fact that he was not awarded the beauty prize at the trial of Paris and Zeus's infidelity with the Pleiad Electra, from whose union Dardanus was born, ascendant of the Trojan kings). Later Zeus ascended Ganymede into the sky as the constellation Aquarius (the Water Bearer), which is related to that of Aquila (the Eagle).

Ganimede's father missed his son. In compensation, Zeus sent Hermes with a golden vine, the work of Hephaestus, and two horses so fast they could run on water. In addition, Hermes assured Ganymede's father that the boy was now immortal and that he would be cupbearer to the gods, a position of great distinction. The theme of the father recurs in many of the early Greek myths of love between men, suggesting that the homosexual relationships symbolized by these stories took place with the consent of the father.

Greek Interpretations

Ganymede was of Trojan rather than Greek origin, which identifies him as part of the earliest level of pre-Hellenic Aegean mythology. Plato opined in his Timaeus that the myth of Ganymede had been invented by the Cretans —Minoan Crete was a power center of pre-Hellenic culture— to justify their homosexual inclinations, which were later imported by Greece., in which the Greek authors agree. Homer is not concerned with the erotic aspect of Ganymede's abduction, but it is certainly in an erotic context that the goddess refers to the blonde Trojan beauty in the Homeric hymn to Aphrodite, mentioning Zeus's love for the boy as part of his attraction to the Trojan Anchises.

Roman interpretations

The Roman poet Ovid adds vivid details and veiled ironies directed at critics of love between men: mature guardians striving to win it back and Ganymede's dogs barking uselessly at the sky (Carmina x). In the Thebaid (i.549) of Statius a cup is described carved with an iconography of the myth of Ganymede: «Here the Phrygian hunter is carried through the air on tawny wings, the Gargara mountain range sinks as he ascends, and Troy vanishes beneath him; sad are his comrades; in vain the dogs tire their throats by barking, chase their envelope or howl at the clouds.»

Alternate version

In a possible alternative version, the Titaness Eos, goddess of the dawn and expert in male beauty, kidnapped Ganymede along with her brother Tithonus, her most remembered husband, who was granted immortality, but not eternal youth. In fact Tithonus lived forever but grew older and older, in what is a classic example of the mythological element of the trick blessing. Like Ganymede, Tithonus is placed in the lineage of the Dardanids through Tros, an eponym of Troy. Robert Graves ( The Greek Myths ) interpreted the substitution of Ganymede for Tithonus in a few references to the myth as misinterpretations of an archaic icon that would have shown the consort of the winged goddess carrying a libatory in her hand.. (Quoted in the scholium On Apollonius Rhodio iii.115; Virgil, Aeneid i.32; Hyginus, Fables 224.)

Later influence

In Ancient Rome, the passive object of a man's homosexual desire was a catamitus. The word is a corruption of the Greek ganymedes, but has no mythological connotations in Latin. When Ovid briefly outlines the myth (The Metamorphoses x.152-161), Ganymede retains the familiar Greek name for him.

In poetry, Ganymede is a symbol of the ideally beautiful youth and also of homosexual love, sometimes contrasted with Helen of Troy in the role of symbol of love for women.

The main satellite of the planet Jupiter was named Ganymede in honor of the myth of Zeus and Ganymede, since the Roman equivalent of Zeus is Jupiter.

Ganimede in art

Ancient art

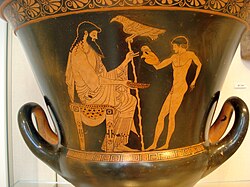

In Athens, vase painters often depicted the mythical story, which was well-suited for all-male symposia or formal banquets. The myth of Ganymede was treated in recognizable contemporary terms, illustrated with the usual behavior in homosexual courtship rituals. In a red-painted Attic krater at the Louvre, Zeus pursues Ganymede on one side, while on the other the youth flees, rolling a hoop while holding aloft a crowing rooster (presumably a courtship gift from Zeus).). In a vessel of the "Achilles pin" Ganymede also flees with a rooster. Ganymede is usually depicted as well-grown, young and muscular, yet engaging in incongruously childish activities (such as rolling a hoop down the street).

Leochares (about 350 BC), an Athenian sculptor who worked with Scopas on the Halicarnassus mausoleum, molded a bronze group of Ganymede and the eagle, an extraordinary work for its ingenious composition, which ventures boldly into the edge of what is allowed by the laws of sculpture, and also for his charming treatment of the young man flying through the air. This sculpture is apparently imitated by a well-known marble group from the Vatican, half life-size. Such gravity-defying Hellenistic feats influenced the arts of the Baroque.

One of the statues at Sperlonga depicts the abduction of Ganymede.

Renaissance and Baroque

In Shakespeare's As You Like It (1599), a comedy of misunderstandings set in the magical Forest of Arden, Celia, dressed as a shepherdess, becomes Aliena (“stranger”) and Rosalind Being "of a taller than general stature", he disguises himself as a boy, Ganymede, an image familiar to the public. Rosalinda takes advantage of her ambiguous charm to seduce Orlando, but also (unintentionally) Phoebe. In this way, by the conventions of the Elizabethan theater in its original conception, the young man who played Rosalinda dressed as a boy and was then courted by another boy who played Phoebe.

When the painter and architect Baldassarre Peruzzi included a panel of The Abduction of Ganymede on a ceiling in the Villa Farnesina in Rome (circa 1509-1514), the long blond hair and girlish pose of Ganymede makes him unidentifiable at first glance, although he holds the eagle's wing without resistance. In Correggio's (1439-1534) version in Vienna Ganymede's grip is more intimate. Rubens' version portrays a fully grown young country boy. But when Rembrandt paints the Abduction of Ganymede for a Dutch Calvinist patron in 1635, the classic erotic overtones are given a biting twist: the dark eagle carries a plump cherubic baby on its back, crying and urinating in fear (Dresden Picture Gallery). This is a pictographic formulation of the old condemnation of pedophiles who exploit young children.

The Spanish poet Juan de Arguijo wrote a poem in 1605 entitled Júpiter a Ganimedes, and Luis de Góngora uses the myth of Ganymede in Las Soledades and in his famous sonnet The sweet mouth that to taste invites....

Wilhelm Vollmer illustrated the article "Ganymede" in his Wörterbuch der Mythologie aller Völker (Stuttgart, 1874) with an engraving of a "Roman relief" showing a seated, bearded Zeus holding the cup to one side so she could embrace a naked Ganymede. However, said engraving was nothing more than a copy of the Roman fresco forged by Anton Raphael Mengs, as a joke for the 18th century art critic. Johann Winckelmann, who was getting desperate in his search for Greek and Roman homoerotic antiquities. This story is referred to very briefly by Goethe in his Italienische Reise[1].

19th century

Franz Schubert set to music in 1817 a poem by Goethe entitled Ganymed, which he published in his Opus 19, no. 3 (D. 544).

In the 19th century the bachelor Duke of Devonshire added to his sculpture gallery in Chatsworth Adamo Tadolini's neoclassical piece Ganymede and the Eagle, in which an exuberantly reclining Ganymede, embraced by one wing, is about to exchange a kiss with the eagle. The delicate cup in his hand is made of gilt bronze, lending a haunting immediacy and realism to the white marble group.

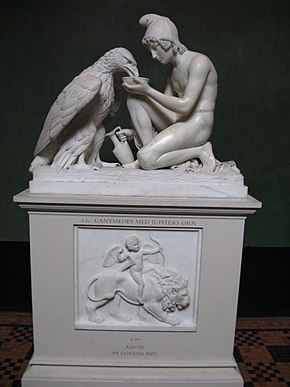

The Danish artist Bertel Thorvaldsen sculpted in 1817 a sculpture dedicated to the scene of Ganymede and the eagle.

20th century

At the beginning of the 20th century, the classic theme of the abduction of Ganymede by Zeus was put at the service of commercial enterprises. Based on an 1892 lithograph by F. Kirchbach, the Anheuser-Busch brewery launched an advertising campaign in 1904 extolling the benefits of Budweiser beer. Until the early 1990s, collectibles were released on the poster graphics.

Old fonts

- Iliad, V, 265; XX, 232.

- V: Spanish text on Wikisource; see vv. 251 - 273.

- Greek text.

- XX: Spanish text on Wikisource; see vv. 199 - 258.

- Greek text.

- V: Spanish text on Wikisource; see vv. 251 - 273.

- Little Iliad, fragment 7.

- English text in the Gutenberg Project.

- Homerical hymns (κομνοιμνοι).

- V: Aphrodite ( φροδετιν), 203 - 217.

- Spanish text, with introduction, in Scribd; the text of the hymn V, from the page. 54 electronic reproduction.

- English text in the Perseus Project; active labels can be used focus (to change the annotations in English or Greek text) and load (for simultaneous display of text and annotations or for bilingual text).

- Spanish text, with introduction, in Scribd; the text of the hymn V, from the page. 54 electronic reproduction.

- V: Aphrodite ( φροδετιν), 203 - 217.

- TEOGNIS: Elegías, II, 1.345 - 1.350.

- Italian text.

- Greek text on Wikisource.

- Italian text.

- EURÍPIDES: Ifigenia in Áulide, 1,051

- PLATION: Fedro (φαίδρος), XXXVI, 255 c.

- Italian text.

- Spanish text on Wikisource; search "[305]" for half of the page.

- Greek text on Wikisource.

- APOLONIO RODIO: Argonáuticas, III, 112 et seq.

- 115 - 118: Italian text.

- 106 et seq.: Greek text.

- 115 - 118: Italian text.

- STRABAN: Geography (Русский), XIII, 1, 11.

- Greek text on Wikisource.

- PAUSANIAS: Description of GreeceV, 24, 5; V, 26, 2 - 3.

- V, 24: French text.

- Greek text.

- V, 24, 5: English text.

- V, 24, 5: Greek text.

- V, 24: French text.

- DIODORS SYCULE: Historical LibraryIV, 75, 3.

- English text.

- Greek text on Wikisource.

- English text.

- HIGINO: Fables (Fabulae), 224 and 271.

- 224: Who among mortals were made immortal (Qui facti sunt ex mortalibus immortal).

- Italian text.

- English text on Theoi site.

- Latin text on the site of the Bibliotheca Augustana (Augsburg).

- Ed. of 1872 on the Internet Archive: Latin text in electronic facsimile.

- 271: Who were very beautiful ephebos (Qui ephebi formosissimi fuerunt).

- English text in Theoi.

- Latin text on the site of the Bibliotheca Augustana.

- Ed. of 1872 on the Internet Archive: Latin text in electronic facsimile.

- English text in Theoi.

- 224: Who among mortals were made immortal (Qui facti sunt ex mortalibus immortal).

- HIGINO: Poetry astronomy (Astronomica), II, 16 and 29.

- Italian texts.

- 16: The eagle.

- English text in Theoi.

- 29: Aquarium or The Watering.

- English text in Theoi.

- 16: The eagle.

- Italian texts.

- OVIDIO: MetamorphosisX, 155 - 161.

- Spanish text on Wikisource.

- English text, with electronic index, in the Perseus Project. Active labels can be used."focus"(to change Arthur Golding's 1567 English text or Latin text) and "load"(for comparison between English texts or for bilingual text).

- X: Latin text on Wikisource.

- English text, with electronic index, in the Perseus Project. Active labels can be used."focus"(to change Arthur Golding's 1567 English text or Latin text) and "load"(for comparison between English texts or for bilingual text).

- Spanish text on Wikisource.

- VIRGILIO: EneidaI, 28; V, 252.

- I: Spanish text on Wikisource.

- Latin text.

- V, 249 - 255: Italian text.

- V: Spanish text.

- V: Latin text.

- V: Spanish text.

- I: Spanish text on Wikisource.

- VALERIO FLACO: Argonáuticas, II, 414; V, 690.

- II: Latin text on the site The Latin Library.

- V: Latin text on the same site.

- STAGE: Tebaida1.549.

- Tebaida: Spanish text; translation of Juan de Arjona. University of Valencia.

- Latin text.

- Tebaida: Spanish text; translation of Juan de Arjona. University of Valencia.

- STAGE: Silvas, III, 4, 13.

- Latin text.

- APULEYO: The golden assVI, 15 and 24.

- VI: Spanish text in Wikisource.

- Latin text: 15; 24.

- VI: Spanish text in Wikisource.

- SAMÓSATA PLACE: Dialogues of the gods.

- PANPOLIS NOON: Dionysy.

- Suda: Ilion; Minos

Contenido relacionado

Inca mythology

Leuce

Xochitónal

Suzaku

Siegfried (character)