Galician-Portuguese subgroup

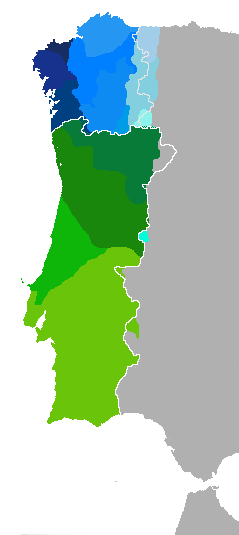

The Gallaic-Portuguese languages form a linguistic subgroup within the Western Ibero-Romance group, which includes the following languages:

- Gallego (Spain)

- Eonaviego (Spain)

- Portuguese (Portugal)

- Judeoportugués (†) (International)

- Fala (Spain) (No official)

Old Galician-Portuguese was the origin of this subgroup.

Characteristics and origin of these languages

Kurt Baldinger perfectly describes the character of this subgroup when he points out that the Galician-Portuguese languages show the typical conservative and revolutionary double aspect of a marginal area. Along with profoundly revolutionary traits, such as the loss of intervocalic -n- (or nasalization), the loss of -L-, the shift from the groups pl-, cl-, fl- to ch, conservative traits oppose - especially of a lexical- and syntactic type.

The conservative features of the Galician-Portuguese languages are justified by the form and origin of the romanization process of the northwest of the peninsula, undoubtedly coming from the South and specifically from Baetica, (the earliest romanized region of the peninsula). It is thus justified that in the Galician-Portuguese, as in the rest of the Ibero-Western languages, words considered as archaisms are preserved already in the Italic Latin of the 1st century, (prior to the romanization of the peninsular Northwest), thus the conservation of cuius, cuia, cuium that already in Cicero is an archaism, the conservation of 'fabulari' in front of 'parlare', (cast. to speak, port. to falar., etc.), 'quaerere' versus 'volere', 'percuntari' versus 'questionare', campsare, etc. As Griera pointed out in 1922, since ancient times the theory of the two directions in the Romanization of the Iberian Peninsula had been revealed, which is confirmed by the division of the peninsular into two provinces, citerior and ulterior, representative of the centers of power of the empire located in Betica and Tarragona. Certainly the areas of influence do not correspond to the linguistic groups studied, but it must be borne in mind that the incorporation of the northern territories into Romanity was after said division. For Wilhelm Meyer Lübke, these two centers of romanization present great contrasts of a cultural, linguistic, etc. type. Betica, with its flourishing civic culture and its active cultural life, is opposed by the decidedly military and vulgar character of Tarragona. The conservative character of the South would surely respond to this cultural and social differentiation, which would explain the also conservative character of Portuguese: conservation of the final -U, of the groups AI, AU, MB, of the distinction between the vowels o and e closed and open, but also the more open character to the innovations of the Northwest.

On the contrary, innovative features, such as the loss of -n- and -l- (and in a somewhat broader field also the palatization of the groups pl-, cl-, fl-), were initially produced, only, in the NW corner of the peninsula -it is missing in the Mozarabic documents and in the place names of the center and south-, being carried by the Reconquista towards the South. It must be taken into account that the province of Gallaecia, created in 216 by Caracalla, included most of the current provinces of León and Asturias, maintaining a certain autonomy during the period of the Germanic invasions. The Roman provincial configuration explains many of the characteristics of the languages of the NW peninsula, not only in the Galician-Portuguese sphere but also in Leonese and western Asturian. This territory is also identified with the pre-Roman social organization system identified by the inverted C sign, which is so frequent in the epigraphy of the northwestern quadrant of the peninsula. Archaeologists have tried to relate this symbol to a mode of social organization that would link the various towns within a specific territorial framework, as opposed to other types of supra-familial organizations evidenced in epigraphy under the more common terms gens, gentilites and genitives in the plural. in the center of the peninsula.

Regarding the -n- caediza, various investigations have confirmed this North-South influence of the Reconquest. Thus, Herculano de Carvalho, has argued this trend in the field of objects of practical use, referring to two types of threshing floor that had been taken, with the Reconquest, to the South, together with all their own terminology: malho - mangual - moual, as names of the instrument, pírtigo and mangoeira - moueira as the name of the two main pieces of the threshing floor (mango and mallet). In his book, which follows the line of research by Worter und Sachen, "for the first time in Portugal a methodical study of Portuguese is found —here restricted to debulha terminology— following the advance of northern Portuguese to the south during the reconquest in all its phases, taking into consideration two centers, which will be formed in the course of history, for their regions”. Be that as it may, it is this feature, the treatment of nasality, that will contribute the most to unite all these languages in a specific group differentiated from the rest of the other peninsular languages".

Another of the features of the Galician-Portuguese languages is the tendency towards the sonority of the stops, remember that the languages of the Celtic-Atlantic group do not know many of the voiceless stops. This feature is common to all of western Romania up to the Spezia Rimini line, and as is known gave rise to the voicing of the voiceless intervocalics cipolla>cebolla, Lepere>Liebre, according to spellings preserved since the 16th century II, voicing that is prior to the fall of the internal postonic vowel. In the Galician or Portuguese languages we find a manifestation of this superstratum in the velarization of the clustered interior consonants salto>souto, altarium>outeiro, agru>eiro>flagrare, fructum>fruito, flagrare>cheirar, etc.

First documents of the Galician-Portuguese subgroup

Although the first texts in the Galician-Portuguese language are relatively late compared to Spanish, being the first documented from the XII century, the essential phonetic particularities of these languages predate the X century, the loss of -N- is documented directly from the IX [850 mendiz 194, 882 elemosias, 959 moimenta, 968 Coinbrie, etc.] 195, and the loss of -L - from the X century [919 Froiai, Froiaz; 959 Floiaz, 983 Froia; Vasconcelos, Lições, p. 291, citation: 995 Fiiz < HAPPY, Fafia > FÁFILA] 196. The oldest literary document known today is the satirical song Ora faz ost'o senhor de Navarra by Joam Soares Paiva, written around the year 1200. From the beginning of the century XIII date the first non-literary documents in Galician, testament of Elvira Sánchiz, (1191), Noticia de Torto (1211), the Testament of Afonso III of Portugal (1214) and Fuero de Castro Caldelas (1228).

Comparison chart

The following is a comparative table of the languages of the Galician-Portuguese family with reference to Latin and its translation into Spanish.

| Latin (ac.) | Gallego-portugués | Portuguese | Gallego | Eonaviego | Xalima candle | Portuguese Judeo | Castellano |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| altu(m) | outo | High | High | High | Altu | (...) | High |

| arbor(em) | arvo | arvore | arbore | tree (old tree) | Tree | arvo | tree |

| asciata(m) | aixada | enxada | aixada | eixada | Essada | (...) | road |

| auru(m) | Ouro | Ouro | Ouro | Ouro | Ouro | gold/oyro | Gold |

| quattuor(rum) | quatro | quatro | Catro | Four | Cuatru | kuatro | Four |

| brácchiu(m) | braço | braço | arm | arm | arm | braço | arm |

| clu(m) | ceo | ceu | ceo | cêlo | ceu | ceo | Heaven |

| cláve(m) | chave | chave | chave | chave | chavi | zhave | Key |

| dinner (m) | c/ | ceia | cea | aunt | cea | çea | Dinner |

| calu (m) | Dig. | Dig. | Horse | horse/horse | Wow. | kabalo | Horse |

| digit(m) | finger | finger | finger | dido | deo | finger | finger |

| dubitā(m) | dubious/sweet | life | dúbida | (ant. tb dolda) | dúbida | divide | doubt |

| duo/duas | dous/duas | dois/duas | dous/dúas | dous/dúas | dois /dúas | dous /dúas | Two. |

| . hómine(m) | home | homem | home | Hòme | home | home | man |

| (m) | livro | livro | book | book/llibro | book | book | book |

| lūna(m) | ♪ | lua | Crane | toll | lua | luah | Moon |

| lana(m) | lãa | lã | ♪ | (ant. lã/llã) | Lan | laah | wool |

| mānu(m) | mão | mão | man | Mao | man | manym | hand |

| multu(m) | ♪ | ♪ | Moito | ♪ | mutu | Very. | a lot. |

| fundamentalu(m) | enteiro | inteiro | enteiro | enteiro | enteiro | enteyro | whole |

| nickname(m) | noite | noite | noite | noite | noiti | No. | night |

| péctu(m) | Peito | Peito | Peito | Peito | peitu | Peyto | chest |

| planu (m) | chão | chão | chan | Bye. | chau | zhao | llano |

| plenu (m) | Cheese | Cheio | Czech | chen/chío | cheu | zheo | full |

| quī / quem | quem | quem | What? | what? | What? | ken | who |

| sucu(m) | çume | sumo | zume | zume | Sumi | çumo | juice |

| tabula (m) | taboa | tábua | Taboa | job | Taboa | taboah | Table |

| pair(m) | wall | wall | wall | wall | paréi | wall | wall |

| ūna(m) | ignora | Uma | unha | Crane | üa | üah | One |

| cerasium | sore | eyebrow | cereixa | cereixa | zereija | (...) | Cherry |

| vétulu(m) | hair | velho | hair | vèyo | hair | velyo | Old man |

| vicinnus(m) | ♪ | vizinho | Veciño | vecín/vecío | vizinho | I do. | neighbor |

| Latin | Gallego-portugués | Portuguese | Gallego | Eonaviego | Xalima candle | Portuguese Judeo | Castellano |