Galician

Galician Galician (galego in Galician) is a Romance language of the Galician-Portuguese subgroup spoken mainly in the autonomous community of Galicia, Spain. It is closely related to Portuguese, with which it formed a linguistic unit (Galaico-Portuguese) during the Middle Ages.

Different varieties of Galician are also spoken in the areas bordering Galicia: the Eo-Navia region, in western Asturias, and in the western El Bierzo and Sanabria regions, northwest of Castilla y León.

Some linguists also consider as part of the Galician language the speech of the three towns in the Jálama Valley, in the extreme northwest of Extremadura, locally called fala or with a local name for each town.

Historical, social and cultural aspects

Geographic distribution

Galicia

Galician is spoken throughout the autonomous community of Galicia, where it is the proper and co-official language along with Spanish. There are several dialect variants within the territory.

Castile and Leon

Galician is spoken in the northwestern areas of Castilla y León that border Galicia. Speakers are found in the western part of the El Bierzo region in the province of León, decreasing in number and relevance the further east, as well as in the province of Zamora, in the western part of the Sanabria region, known as Las Portholes.

In El Bierzo, Galician is spoken in 23 municipalities, specifically in Balboa, Barjas, Borrenes, Cacabelos, Candín, Carucedo, Carracedelo, Corullón, Oencia, Puente de Domingo Flórez, Sobrado, Toral de los Vados, Trabadelo, Vega de Valcarce and Villafranca del Bierzo, and in part of those of Arganza, Benuza, Camponaraya, Fabero, Peranzanes, Ponferrada, Priaranza del Bierzo and Vega de Espinareda.

In the area of Las Portillas, Galician is spoken in 5 municipalities: Hermisende, Lubián, Pías and Porto, and also in the district of Calabor, in the municipality of Pedralba de la Pradería.

Its regulated teaching is allowed in El Bierzo, according to an agreement between the Education Department of the Galician Government and the Education Department of Castilla y León. 844 students study it in nine municipalities of Berciano, taught by 47 teachers. In addition, in the Statute of Autonomy of Castilla y León, in its 5th article, it is indicated: "The Galician language and the linguistic modalities will enjoy respect and protection in the places where they are habitually used".

Asturias

There is a markedly political controversy about the identity of the Galician language spoken in the neighboring councils of the Principality of Asturias belonging to the Eo-Navia region, that is, whether it should be included within the Galician dialect varieties oriental (Real Academia Galega, Instituto Galego da Lingua, Promotora Española de Lingüística (PROEL), which include Eonaviego within the eastern block of Galician under the name of Galician-Asturian) or instead be considered a language with its own entity within the Asturian-Leonese group as postulated by the Academy of Asturian Language.

Eonaviego is spoken in 19 councils, in all of Boal, Castropol, Coaña, El Franco, Grandas de Salime, Ibias, Illano, Pesoz, San Martín de Oscos, Santa Eulalia de Oscos, San Tirso de Abres, Tapia de Casariego, Taramundi, Vegadeo and Villanueva de Oscos, as well as in the western zone of the councils of Allande, Degaña, Navia and Villayón.

Extremadura

In three municipalities of Cáceres, on the border with Portugal, in the Jálama Valley (Valverde del Fresno, Eljas and San Martín de Trevejo) Fala is spoken, a language on which there is no agreement as to whether it is a third branch of Galician- Portuguese from the Iberian Peninsula, an old Portuguese from the Beiras with a Leonese and Castilian superstrata or a Galician with a Leonese and Castilian superstrata, some historians affirming that it comes from the Galicians participating in the Reconquest who settled in those areas. While the Galician Nationalist Bloc (BNG) proposed to introduce the teaching of Galician in this region, the Junta de Extremadura flatly rejected the proposal.

Other territories

A 2003 linguistic survey in Catalonia by its autonomous government revealed Galician speakers in the region. Population extrapolation placed 61,400 Catalan inhabitants who considered Galician as their first language, 21,000 who considered it their own language, and 11,300 who considered it their habitual language.

Galician communities in Latin America continue to speak the language, especially in Buenos Aires (Argentina), Caracas (Venezuela), Montevideo (Uruguay), Havana (Cuba) and Mexico City. In the rest of Europe they keep it rather precariously, and in Brazil it subsists with adaptations and twists from Brazilian Portuguese.

Regarding the number of speakers, Galician ranks 146th in the world list, which includes more than 6,700 languages.

History

Galician, like all Romance languages, comes from the Vulgar Latin spoken in the ancient Roman province of Gallaecia, which included the territory of present-day Galicia, the north of present-day Portugal, Asturias, the present-day province of León and part of Zamora.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the different variants of Latin were consolidated. One of them was the medieval Galician or Galician-Portuguese.

The oldest surviving document written in Galician produced in Galicia is the Pact of Irmãos (1173-1175), which precedes the charter of Castro Caldelas ("Foro do bo burgo do Castro Caldelas") of 1228, which until recently it was the oldest known. It is the one granted by King Alfonso IX in April of that year to the town of Orensa. The oldest Latin-Galician-Portuguese document was found in Portugal, and is a donation to the church of Sozello, which is in the National Archive of Torre do Tombo, and is dated around the year 870 AD. c.

During the Middle Ages, Galician-Portuguese was, along with Occitan, the habitual language of troubadour poetic creation throughout the Iberian Peninsula (see Galician-Portuguese lyric). The King of Castile Alfonso X the Wise wrote his Cantigas de Santa María in Galician-Portuguese.

Starting in the 12th century, when the County of Portugal became independent from the Kingdom of León, medieval Galician began to diverge into two modern languages: current Galician and Portuguese. Both were fully consolidated around the XIV century.

The Castilian pre-eminence, which occurred after the influence of the Castilian nobility over the Galician nobility at the end of the Middle Ages, in practice led to the abandonment of this language in the public sphere (diglossia). The influence of Spanish, as well as the isolation (which to a large extent contributed to maintaining terms that in Portuguese came to be classified as archaisms), caused Galician to distance itself from Portuguese, the official language of the kingdom of Portugal, which also had a major overseas expansion. In Galicia, this period, which lasted until the end of the XIX century, is known as the dark centuries (dark centuries)

At the end of the XIX century, the literary movement known as Rexurdimento took place, with the which, thanks to authors such as Rosalía de Castro, Curros Enríquez, Valentín Lamas Carvajal or Eduardo Pondal, Galician became a literary language, although almost exclusively used in poetry. At the beginning of the XX century, it began to be used in rallies by Galician parties. In 1906 the Royal Galician Academy was founded, an institution in charge of the protection and dissemination of the language. In the 1936 Statute of Autonomy, Galician is recognized as a co-official language, along with Spanish. However, after the Civil War a period of linguistic repression followed, which meant that during the forties almost all Galician literature was written from exile.[citation required] However, an important change took place during the 1970s, and since 1978 Galician has been recognized as official in Galicia by the Spanish Constitution and by the Statute of Autonomy of 1981.

Currently, the use of Galician over Spanish is the majority in rural areas, and its use is less in large cities, due to the influence of Spanish. Even so, according to the most recent study on the language customs of the Galician population, around eighty percent of the population uses it, and according to a 2001 census, 91.04% of the population can speak Galician. Although it is the most widely spoken language among those of the historical Spanish nationalities, it enjoys less social recognition than, for example, Catalan, which also it has suffered repressive centralist policies during the Franco regime,[citation required] probably because since the end of the Middle Ages it was identified by the Galicians themselves as the language of the peasants and the lower layers of society. It must also be taken into account that Galicia received few immigrants, unlike other areas of Spain with their own language (such as Catalonia, the Valencian Community, the Balearic Islands and the Basque Country) that received many immigrants from Spanish-speaking regions, which have notably influenced the respective linguistic maps. In practice, a large part of Galician speakers speak a poorly maintained variety of Galician, which introduces numerous lexical, phonetic and prosodic Spanish expressions, although it maintains a clearly Galician essence and constructions, although in urban environments an authentic mix of Spanish and Galician called traditionally castrapo.

Every year the Día das Letras Galegas (May 17) is celebrated, dedicated to a writer in this language chosen by the Royal Galician Academy from among those who died more than ten years ago. This day is used by official bodies and by socio-cultural groups to preserve and promote the use and knowledge of both the Galician language and literature.

Use of Galician

Galicia

Galician is still the majority language in Galicia, however there is a tendency for Spanish to gain ground in daily use. According to the IGE, Galician is spoken more in towns with less than 10,000 inhabitants and is spoken plus Spanish in large and medium-sized cities. In cities with more than 50,000 inhabitants, those who are monolingual in Spanish are the majority group. In La Coruña, Vigo, Santiago and Pontevedra, the majority group is monolingual in Spanish.

Galician as the habitual language is less frequent the younger the speaker. In 2018, 44.1% of children between the ages of 5 and 14 always spoke Spanish. 48.4% of people over 65 years of age always spoke Galician.

| Use of Galician and Spanish in Galicia (2003-2018) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | 2008 | 2013 | 2018 | |||||

| Always speak in Galician | 42.9 per cent | 1.112.670 | 29.9 per cent | 779.297 | 30.8% | 789.157 | 30.3% | 778.670 |

| Speak more in Galician than in Spanish | 18.2 per cent | 471.781 | 26.4 per cent | 687.618 | 20,0% | 513.325 | 21.6% | 553.338 |

| Speak more in Spanish than in Galician | 18.7 per cent | 484.881 | 22.5 per cent | 583.880 | 22,0% | 563.135 | 23.1 per cent | 593.997 |

| Always speak in Spanish | 19.6 per cent | 506.322 | 20,0% | 521.606 | 25.9 per cent | 664.052 | 24.2% | 621.474 |

Varieties

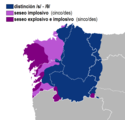

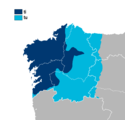

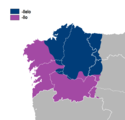

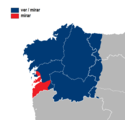

According to the dialectological separation of Galicia used by organizations such as the Royal Galician Academy (RAG) and the Instituto da Lingua Galega (ILG), there are three recognized linguistic blocks, each with its own peculiarities. The western block covers the Rías Bajas and reaches the area of Santiago de Compostela. The central one occupies the vast majority of Galician territory, while the eastern one includes the easternmost areas of Galicia and the border territories of Asturias [citation required], León and Zamora. These blocks are characterized by the way of constructing the plural of the words ending in -n, being the isoglosses that delimit them cans/cas (western and central blocks, respectively) and cas/cais (central and eastern blocks, also respectively).

The Portuguese philologist Cintra, who studied the Galician dialects as belonging to the Galician-Portuguese diasystem and whose works are considered a reference in Portugal, preferred to separate the Galician territory into two areas: the western one, which presents gheada (aspiration of the phoneme / g/ becoming an aspirated /h/ similar to that of English) and the oriental, which does not present this phenomenon.

There is a very conservative eastern area that suppresses the "n" more radically ("úa" for "unha", "razois" for Western "razons" or "razós" from the center). There is also a North to South evolution in the use of the Portuguese/Asturleonese imperative <-ái> by central Galician <-ade> and the Galician-Asturian <aide> ("calái", "probáino" for "calade"/"calaide" and "probádeo"/ " Probáidelo".In Eastern Galician the Asturian diminutive <-in>, which becomes <-ía>("rapacín" and "pequenín", occurs more frequently than in feminine are "rapacía" and "pequenía") by deletion of <n>.The correspondence with Leonese can be noted in the lexicon ("naide" for &# 34;none", e.g.) as a consequence of the anticipation of the epentic yod typical of the Galician-Portuguese languages, palatalization of the initial <l> ("llobo", by " 34;wolf"). This influence is not surprising, since it also occurs in the opposite direction: Galician features in western Leonese.

Examples of isoglosses of the Galician language

Dissemination of Galician

Throughout history there have been different groups or associations that have promoted the spread of the Galician language. Some of these representatives are, for example, the Grupo Nós or the Irmandades da Fala. At present and with the advancement of new technologies, online initiatives have emerged such as the web somoscultura.gal or podgalego.agora.gal

Regulatory function

According to the Statute of Autonomy of Galicia, the autonomous community has exclusive powers in the promotion and teaching of Galician (article 27). Such competencies were developed through the Decree for the Standardization of the Galician Language (Decree 173/1982, of November 17) and the Law of Linguistic Normalization (Law 3/1983, of June 15).

In the first, it is provided that the «Normas ortográficas e morpholóxicas do Idioma Galego» (NOMIGa), prepared jointly in 1982 by the Royal Galician Academy (RAG) and the Instituto da Lingua Galega (ILG), were approved as the "basic norm for the orthographic and morphological unity of the Galician Language" (article 1). Also that both entities could, by joint agreement, "provide to the Junta de Galicia as many improvements as they deem appropriate to incorporate into the basic standards". In the second, it is specified (in the Additional Provision) that "in matters relating to the regulations, updating and correct use of the Galician language, what is established by the Royal Galician Academy will be considered as an authoritative criterion".

Reintegrationism

Different cultural entities defend Galician as a diatopic variety of the Galician-Portuguese-African-Brazilian linguistic diasystem, known worldwide as Portuguese, and promote a regulation called "reintegrationist" consisting of the acceptance of a Galician orthography very similar to the Portuguese one. According to the reintegrationists, the difference between the different varieties of the diasystem is comparable to the difference between the different varieties of Spanish. They have also been compared, for almost a century by Johán Vicente Viqueira (in 1919) and reiterated by Ricardo Carvalho Calero in 1981, with the relationship between flamenco and Dutch.

These entities include the Associação de Amizade Galiza-Portugal (AAG-P), the Associaçom Galega da Língua (AGAL) and the Movimento Defesa da Língua (MDL). They propose different, although complementary, strategies to achieve what they consider to be "full normalisation" from Galician, in accordance with what Castelao already defined in Sempre en Galiza: “there will be a day when Galicians and Portuguese will speak and sing in the same language”.

The reintegrationists consider that the NOMIGa consecrate the Castilianization of Galician with the adoption of letters and digraphs, such as Ñ and LL (the fricative palatal value attributed to the letter X is also dependent on the uses of G+e, i and J of Spanish), in the use of suffixes, such as -ble, -ción, -ería (for those considered autochthonous -vel, -çom, -aria) and in the "normativized" on the Castilian pattern.

The Academia Galega da Língua Portuguesa, AGLP (2008), was recently created and received in the Portuguese Parliament.[citation required] Several Galician cultural entities have collaborated in creating a vocabulary presented by the AGLP as a contribution to the Galician lexicon that has been included in the Orthographic Vocabulary of the Portuguese Language (VOLP) and in the dictionary of the Lisbon Academy of Sciences [citation required ] following the policy of the current Spelling Agreement that unifies and aims to bring together all the richness of the varieties of Portuguese at a global level.

Debate between autonomists and reintegrationists

The Galician language is torn between the reintegrationist position ("Galician is a covariety of Portuguese") and the autonomist position ("Galician is an autonomous language of Portuguese"). The reintegration theses have their origin both in native Galician bibliography and in Portuguese philological work, such as the dialectal classification of Portuguese made by the Portuguese romanist Luís Filipe Lindley Cintra. Supporters of the first position call the second, in Galician, "isolationists", while the supporters of the second call the first "lusistas" (despite the different nuances that this word has for reintegrationists, see: Reintegrationism).

Surely, for this reason, the linguistic debate has been vitiated by the political and ideological background that each of these proposals seem to represent. On the one hand, reintegrationism has been identified with Galician nationalism ("arredismo", in Galician)[cita required] or even with territorial reunification with Portugal (although this idea does not seem to underlie the reintegrationist positions in any case)[citation required]. On the other hand, the reintegrationists label the autonomists as "Spanishists" and they denounce that basically they want the disappearance of Galician in favor of Spanish, by bringing it closer to Spanish in spelling, lexicon, phonetics, syntax and morphology. It is a debate that has been classified as internal to the language, but in which there is evidence of a role of proximity or distance from Spanish and the role that both languages should play in society. This has kept the debate locked in irreconcilable positions for a long time.

Both the reintegrationist regulations and the autonomist regulations have political connotations in Galicia, with some defenders of reintegrationism being people linked to Galician nationalism, and some of the defenders of autonomy being people linked to the right, although there are reintegrationists who insistently demand that his position is not related to any political option, and there are Galicians who claim to be "Lusistas" like Adolfo Domínguez, without renouncing the Spanish language.

Nor did the division of the reintegration movement [citation required] contribute to resolving the debate. While the autonomists maintained a single regulation with slight dissensions (thanks above all to the support that being the official regulation supposes), the reintegrationists were divided into two groups that defended two similar regulations but different in terms of their degree of "approximation&# 3. 4; to portuguese. Among them, the one known in its day as the "minimum standard", supported until the 1990s by the BNG, was the most used. This proposal has already been partly accepted as a preferred model within the RAG standard since 2003 when the proximity of a possible government of the BNG-PSdG Board (2005-2009) became evident [citation required]. There has also been the position of the lusistas, who defend the direct use of the orthographic agreement of the Portuguese language to write Galician, since they consider Galician and Portuguese different local varieties of the same language.[quote required].

With regard to universities and research centers in Portugal, the Galician dialects are studied as part of Portuguese, without this having any political connotation.

Last Moves

On July 12, 2003, the Royal Galician Academy approved a modification of the NOMIGa. The modification proposal was preceded by an intense effort aimed at achieving a regulatory consensus sponsored by the Galician Socio-Pedagoxical Association, which resulted in a proposal approved by the Instituto da Lingua Galega and by the Galician Philology departments of the three Galician universities., and supported by a significant number of entities and groups.

The new rules, known as the "concord rules" They were not, however, supported by the reintegrationist and lusista associations, since they considered that the modifications had little scope and marginalized the reintegrationist proposals and they were not even contacted by said officialdom for any consensual proposal.

Some of the modifications introduced are the following:

- The written representation of the so-called "second form" of the article is disregarded; thus, it is advised to write: "change as cousas" instead of the previously recommended "change-the cousas".[chuckles]required]

- It is recommended to write all together words such as: "souls", "love", "devading" or "accused" (which were previously written separately).

- It is recommended to use the '-aria' endings (as in "concellaria") and the 'ao' contraction (instead of 'o')[chuckles]required], although the -ble ("impossible") is still recommended against -bel ("impossible")[chuckles]required]. The use of interrogation and exclamation signs is also recommended as a preferred at the end of the sentence.

- New words are included with the termination '-zo' or '-za' (which were previously written only with '-cio', '-cia'), such as "spazo", "servo", "difference" or "sentenza". In this way, the denomination Galiza is recognized as traditional and literary, and is accepted by the new regulations.

- In general, the letter 'c' disappears from the consonant groups '-ct-' and '-cc-' if they are preceded by the vowels 'i' or 'u'. For example: "dicionary" or "diddo".

- The use of "athe" is supported (=until, preposition, which replaces in many cases the previous ataplace, and deicaTime, "poren" (=yet), "studant" (=studentor the relative article "cuxo" (=whose), previously not admitted. The letter 'q' is called "which" instead of "cu".

Movements in reintegrationism The different gradations of approximation to Portuguese now seem to accept the 1990 Orthographic Agreement as a referential element, since both the AGLP Academy directly advocates its use and the AGAL association has recently (2017) adapted its orthographic proposal to said agreement (Modern Galician Orthography)..

Autonomism, reintegrationism and Lusism in Galician society

The influence of the Spanish language on Galician has caused its regulations to establish standards that are slightly distanced from spoken Galician. For example, some of the reintegrationist proposals (such as the suffixes -vel, -çom, -aria) and autonomists (such as the suffixes -bel, -za, -aria).

A part of Galician society perceives Galician and Portuguese as different languages and another part perceives Galician and Portuguese as dialects of the same language. The intelligibility between both languages is 85% (estimated by R. A. Hall, Jr., 1989). This perception also has geographical-dialectal influences, being mainly in the people of Pontevedra and the south of Ourense, where they are perceived as dialects of the same language.

The three linguistic currents have their respective weak points. The «autonomist proposal» adopts a large part of the solutions of the spelling of Spanish, which in many cases makes it impossible to represent the phonemes that do not exist in Spanish in writing. The "reintegrationist proposal" is unknown by Galician society, which in some cases causes the erroneous association of this regulation with Lusism or with the phonetics of Portuguese, the existing phonetic differences being evident. In the "Lusian proposal", some of the orthographic solutions shared with Portuguese are not necessary in Galician, since Galician does not use some Portuguese phonemes and does not need to represent them in writing. Regarding these last two positions, there are no official statistics on which to base oneself to determine their degree of implantation in society.

All the regulations preserve graphic signs that lack phonetic meaning, for example the official regulations preserve graphic signs, some of them inherited from the Castilian orthography, such as (b/v, c/z, c/qu to designate the same phoneme or mute h).

However, with respect to the international orthographic agreement, it has also been mentioned that given the inherent conventionality of any graphic standard, attempts have even been made to demonstrate that the unified spelling of current Portuguese is actually closer or more adequate to represent the Galician variety of the language than for any other of the standard varieties of Portuguese (Brazil, Portugal, etc.)

Media in Galician

The main media outlets that use Galician are:

- Corporación Radio e Televisión de Galicia (CRTVG): public media, founded in 1984 and managed by the Junta de Galicia.

- Public television: TVG.

- The public radio of Galicia: Radio Galega.

- Online newspapers We are Galiza, Galicia Confidencial, Public Praza and Diario Liberdade.

- On paper, today, We are Galiza has a printed weekly publication and Novas da Galiza edit a monthly newspaper.

On January 2, 2020, the newspaper Nós Diario was born, which is published from Tuesday to Saturday, with delivery of Sermos magazine on Saturdays together with the newspaper.

Linguistic description

Phonology

- Vocals

The Galician language has seven vowels in tonic position (unlike Portuguese, whose vowel system includes twelve phonemes), with the exception of the Ancarese area that presents nasal vocalism, which means twelve vowels (just like Portuguese). The vowels are /i/, /e/, /ɛ/, /a/, /ɔ/, /o/, /o/. The difference between /e/ and /ɛ/, and between /ɔ/ and /o/ resides in the degree of opening: /ɛ/ and /ɔ/ are more open than /e/ and /either/. This vowel system is the same as Vulgar Latin.

The vowel system is reduced to five vowels in postonic syllables, and only three in unstressed final position: [ ɪ ʊ ɐ ] (which can instead be transcribed as [e̝, o̝, a̝]). In some cases, the vowels of the final unstressed set appear in other positions, as for example in the word thermonuclear [ˌtɛɾmʊnukleˈaɾ], because the prefix thermo- is pronounced [ˈtɛɾmʊ].

Unstressed close mid vowels and open mid vowels (/e ~ ɛ / and / o ~ ɔ /) can occur in a complementary distribution (for example, ovella [oˈβeʎɐ] 'sheep' / omit [ɔmiˈtiɾ] 'omit' and little [peˈkenʊ] 'little' / issue [ɛmiˈtiɾ] 'cast'), with some minimal pairs such as botar [boˈtaɾ] 'throw' vs. 'throw' botar [bɔˈtaɾ] 'jump'. In pretonic syllables, close/open mid vowels are preserved in derived and compound words (e.g. corda [ˈkɔɾðɐ] 'cord' → cordeiro [ kɔɾˈðejɾʊ] 'rope maker', contrasting with cordeiro [koɾˈðejɾʊ] 'lamb').

Unlike what happens in Portuguese, nasality is not a pertinent feature in Galician vocalism, despite being present in the voiced velar nasal consonant /ŋ/ that interferes with phonation, both in the middle of words (funme, cansei) as at the end of words (heart, truck)

Galician admits 16 diphthongs or combinations of two vowels in the same syllable. These diphthongs are decreasing when the first vowel has a greater degree of opening than the second, and increasing when the reverse occurs.

The decreasing diphthongs of Galician are the following:

- /ai/ (e.g. "laborais")

- /au/ (e.g. "cause")

- /ei/ (e.g. "conselleiro")

- /eu/ (e.g. "defendeu")

- /iu/ (e.g. "viviu")

- /oi/ (e.g. "scooting")

- /ou/ (e.g. "Ourense")

- /ui/ (e.g. "puido")

The growing diphthongs are:

- /ia/ (e.g. "dian")

- /ie/ (e.g. "science")

- /io/ (e.g. "cemiterior")

- /iu/ (e.g. "triomph")

- /ua/ (e.g. "lingua")

- /ue/ (e.g. "frequency")

- /ui/ (e.g. "linguist")

- (e.g. "residue")

There is a marked tendency in speech to separate the vowels of these unions, even when Galician speakers express themselves in Spanish. Thus, for most Galicians, "piano" is a trisyllabic word, and "series" has esdrújula accentuation

Table of classification of Galician vowels:

| Open | Open media | Half closed | Closed | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palatal | - | / | /e/ | /i/ |

| Central | /a/ | - | - | - |

| Velar | - | /// | /o/ | /u/ |

- Consonants

The existing consonants in Galician are:

- b, c, d, f, g, h, l, m, n, ñ, p, q, r, s, t, v, x, z.

Although in dictionaries you can also find the letters j, k, w, y; These are not specific to the language and are only used in foreign words accepted by the regulations. There are also these digraphs: rr, ch, ll, nh, gu, qu; with different sounds to each of the letters separately.

There is also the digraph gh that corresponds to the voiceless fricative pharyngeal phoneme, but its use is exclusive to the oral language of the western variants and it only appears in the written language to transcribe a message orally. Thus, in various areas of Galicia, phenomena called gheada and lisp appear, which in themselves are not errors, but rather the RAG allows them, thus claiming a greater richness in Galician speech.

Classification chart of Galician consonants:

| Occlusive | Fridge | Africa | Lateral | Vibrante | Nasal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sordo | Sonoro | Sordo | Sonoro | Sordo | Sonoro | Sonoro | Simple Sonoro | Multiple Sonoro | Sonoro | |

| Bilabial | /p/ | /b/ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | /m/ |

| Labiodental | - | - | /f/ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Dental | /t/ | /d/ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Interdental | - | - | /θ/ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Alveolar | - | - | /s/ | - | - | - | /l/ | / | /r/ | /n/ |

| Palatal | - | - | / | - | /// | - | /// | - | - | /// |

| Velar | /k/ | /g/ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | /EUR/ |

Comparison with Portuguese

| Gallego (RAG) | Gallego (AGAL) | Portuguese | Portuguese Brazilian | Castellano |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bo day / Bos days | Bom Dia | Bom Dia / Bons dias | Bom Dia | Good morning |

| How are you shaking? | How are you shaking? | What's your name? | ||

| Burning/Amote | Amo-te | I love you / Amo você | I love you / I love you | |

| Desculpe | Excuse me | |||

| Grape | Obrigado | Thank you. | ||

| Benvido / Benvindo | Bem-vindo | Welcome. | ||

| Adeus | Bye. | |||

| Yeah. | Sim | Yes. | ||

| Non | Nom | Não | No. | |

| Can | Cam | Cão | Cachorro (Usa-se minus Cão) | Dog (chuckles) Can) |

| Avó /a. | Avô //хvo/ | Avô / Vô | Grandfather | |

| Xornal | Jornal | Newspaper, daily | ||

| Espello | Espelho | Mirror | ||

| Xuíz / Xuíza | Juice / Juice | Judge / Judge | ||

| Dissex | Desejo | Wish | ||

| Hoxe | Ho | Today | ||

| Pedra | Stone | |||

| Xarope | Jarabe | |||

| Faculty | Faculdade | Faculty | ||

| Difficulty | Dificuldade | Difficulty | ||

| Dereito | Direito | Law | ||

| Estranxeiro | Estrangeiro | Aliens | ||

| Onte | Ontem | Yesterday | ||

| Xogo | Jogo | Game | ||

| Xofre | Enxofre | Sulphur | ||

| Xadrez | Chess | |||

| Opportunity | Opportunity | |||

| Probabilitye | Probabilities | |||

| Gallego (RAG) | Gallego (AGAL) | Portuguese | Astur-leon | Castellano |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noo Pai you're not ceo: | We miss Pai you're not Céu: | Pai Nosso you're not Céu: | Nuesu Pai que tas nu cielu: | Our Father who art in heaven: |

| sanctified sexa or teu nome, veña a nós o teu kingdom e fágase tua vontade aquí na terra coma no ceo. | hallowed bee or Teu nome, come to Nos or Teu kingdom and be feita to Tua vontade here na terra as we Céus. | sanctified bee or Vosso nome, come to Noos or Vosso kingdom, be a feast to Vossa vontade assim na Terra as not Céu. | sanctifyu seya'l tou nome, come to nós el tou reinu, let the tua voluntá eiquí na tierra as nu cielu. | sanctified be thy Name, come unto us thy kingdom, and do thy will in the earth as in heaven. |

| Danos hoxe o noso pan de cada día; | Or we have each day's pam-no-lo hoje; | Or pão nosso de cada día dai hoje; | The nuesu bread of each day give us; | Give us our daily bread today; |

| and perdoanos as nosas ofensas as tamén we forgive noos a quen ten offended us; | and perdoa-nos as nosy offenses as também we lose noos a quem tem offended; | Perdoai-nos as nosy offenses assim as noos we lose to burn us offended; | already forgives the ufias ufias mesmo that we forgive those who ufienden us; | and forgive our trespasses as we also forgive those who trespass against us; |

| e non nos deixes fall na temptation, mais líbranos do mal. | e nom nos deixes cair na tentaçom, mas livra-nos do mal. | e não nos deixeis cair em tentação, mas livrai-nos do mal. | Now nun mos deixes fall into temptation and deliver us from evil. | do not let us fall into temptation, and deliver us from evil. |

| Amen. | Amen. | Amém. | Amen. | Amen. |

Days of the week

| Gallego (RAG) | Gallego (AGAL) | Portuguese | Castellano | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Luns | Second feira | Second-feira | Monday | ||||

| Tuesday | Terza feira | Terça-feira | Tuesday | ||||

| Mércores | Fourth/cut feira | Quarta-feira | Wednesday | ||||

| Xoves | Fifth feira | Quinta-feira | Thursday | ||||

| Venres | Sixth | Sixth-feira | Friday | ||||

| Saturday | |||||||

| Sunday | |||||||

Months of the year

| Gallego (RAG) | Gallego (AGAL) | Portuguese | Castellano | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xaneiro | Rio | January | ||||

| Febreiro | Fevereiro | February | ||||

| March | Março | March | ||||

| April | ||||||

| Maio | May | |||||

| Xuño | Junho | June | ||||

| Xullo | Julho | July | ||||

| August | ||||||

| Awesome | September | |||||

| Outubro | October | |||||

| Novel | November | |||||

| Decembro | Dezembro | December | ||||