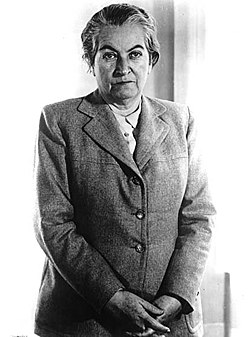

Gabriela Mistral

Gabriela Mistral, pseudonym of Lucila Godoy Alcayaga (Vicuña, April 7, 1889-New York, January 10, 1957), was a poetess, Chilean diplomat, teacher and pedagogue. For her poetic work, she received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1945. She was the first Ibero-American woman and the second Latin American person to receive a Nobel Prize.

Born into a family of modest means, Mistral worked as a teacher in various schools and became an important thinker regarding the role of public education, she came to participate in the reform of the Mexican educational system. In the 1920s, Mistral had an itinerant life serving as consul and representative in international organizations in America and Europe.

As a poet, he is one of the most important figures in Chilean and Latin American literature. His works include Desolation , Tala and Lagar.

Biography

Origin and family

Gabriela Mistral was born in Vicuña on April 7, 1889, under the name Lucila de María Godoi Alcayaga. Currently, in the street where she saw the light, the museum that bears his name. He spent his entire childhood in various locations in the Elqui Valley, in the current Coquimbo Region. Ten days later, her parents took her from Vicuña to the nearby town of La Unión (now called Pisco Elqui). Between the ages of three and nine, Ella Mistral lived in the small town of Montegrande. It would be this place that Mistral considered her hometown; the poet referred to it as her "beloved town" and it was there that she asked to be buried.

Daughter of Juan Jerónimo Godoy Villanueva, a professor and poet of Spanish descent, a native of San Félix, and Petronila Alcayaga Rojas, also of Spanish descent. Her paternal grandparents, natives of the current region of Antofagasta, were Gregorio Godoy and Isabel Villanueva; and her maternal parents, Francisco Alcayaga Barraza and Lucía Rojas Miranda, descendants of families that own land in the Elqui Valley. On her mother's side, Gabriela Mistral had an older half-sister, Emelina Molina Alcayaga, daughter of Rosendo Molina Rojas, who was her first teacher. Because of her father's, she would have had another stepbrother, named Carlos Miguel Godoy Vallejos.

Although her father left home when she was about three years old, Gabriela Mistral loved him and always defended him. She recounts that "shuffling papers", she found some "very beautiful" verses. "Those verses of my father, the first ones I read, awakened my poetic passion," she wrote.

Teacher training

In 1904, she began working as an assistant professor at the Escuela de la Compañía Baja (in La Serena) and sending contributions to the Serenense newspaper El Coquimbo. The following year, he continued writing in it and in La Voz de Elqui, by Vicuña. At the same time he befriended Bernardo Ossandón, a professor and journalist from Serenez who gave him his personal library to study and develop your literary style.

Since 1908, she was a teacher in La Cantera and later in Los Cerrillos, on the way to Ovalle. She did not study to be a teacher, since she did not have money for it. She wanted to enter a normal school from which she was excluded due to religious prejudice. In 1910, she validated her knowledge at the Normal School No. 1 in Santiago and obtained the title of "State Professor", with which she was able to teach in high school. This cost her the rivalry of her colleagues, since she received that title through validation of her knowledge and her experience, without having attended the Pedagogical Institute of the University of Chile.

Lucila Godoy Alcayaga or Gabriela Mistral arrived in Traiguén in Araucanía in October 1910, at the age of 21, to serve as a teacher at the request of the director of the Traiguén Girls' High School. In this regard, she wrote: "Fidelia Valdés put me in high school, she took me to Traiguén & # 34;. In this town she developed functions as a temporary teacher of Labor, Drawing, Hygiene and Home Economics until the first semester of the following year; however, her reception was not as expected, as her colleagues questioned her —as would happen in the other establishments where she served in Chile—, for lack of systematic studies at the Pedagogical Institute. Mistral says in a letter that she has observed the problem of distribution and trials of indigenous lands and pointed out that "they know how to love her land", she was her first contact with the Mapuches. In Traiguén she began the eleven-year journey dedicated to Chilean education in Antofagasta, Los Andes, Punta Arenas, Temuco and Santiago.

Travel and stay in Mexico

Contracted by the government of Mexico, at the request of the Minister of Education José Vasconcelos, who had unleashed a kind of general mobilization in favor of rural education in the country. Gabriela Mistral traveled to Mexico in June 1922; She worked for the Mexican government in the conformation of its new educational system, a model that is maintained almost in its essence, since only reforms have been made.

The moment she touches Mexican soil, our teacher is constantly impressed by the range of motion she is suddenly immersed in. She, who comes from a country of slow social change, suddenly finds herself at the epicenter of a huge tornado. The reform of the peasant school touched Lucila's intimate fibers: the rural, the peasant, the popular, reading as a preferential medium, the creation of libraries. That is to say, just the reverse of the pedagogy, gray and vilified from her own homeland.

Mistral knew the importance of the mission entrusted to him; that is, he was able to foresee the characteristics of that “crusade”. It was an innovation that could well be called a reform and in many ways a revolution. His initial task was simple: to get to Mexico to make Chilean literature known; Soon after, Vasconcelos asks her to prepare a reading book for women and enrolls her in rural and indigenous teaching jobs, where the importance of reading both in its silent mode in the library and in its collective mode in the village are outstanding contributions introduced by Mistral. In both cases it is a festival, similar to that of the theater and religious festivals. His life moves between the Indian towns and the high levels of the intelligentsia and the government. Mistral feels much better with the former. The distance and the new job are polishing his point of view.

Records from both hers and other sources indicate that Gabriela Mistral put her entire body and soul into this task. The radical change of scenery and her activity allowed her to distance herself from the small pedagogical world that had surrounded her for so many years. Behind her were the disputes over her titles and her pettiness and envy. She felt in her own and was rediscovered with the meaning of her life.

Now, this innovative educational reform had nothing to do with what in the Chile of his time received a similar name. Much less has this crusade to do with the pedagogical experiments that the New School is carrying out in Europe and the United States. However, we find realities that are close to it. Mistral lives this period with an intensity unmatched in his entire life. As never before, her task is diverse and challenging, but it is up to what she knows how to do. So that a feeling of accomplishment and fullness will accompany you in these two years. In a way, there will be a reunion with pedagogy, that authentic one with children. Her participation in the educational crusade will be important, but not decisive for her achievement. This will already be underway when she arrives and although her contributions will lead to the book Readings for women , commissioned by Vasconcelos, her task in the missions will be integrated as support for a movement that already Has a life of its own.

Mexico was his first port of call to travel throughout the American continent. From this, he was also a sympathizer of the Latin American movement and thought of the region as a great country, about which he writes his poem Cordillera (1957, in Recados, contando a Chile ).

Return to Chile

In 1925, when she returned to Chile, she was appointed Chilean delegate to the Institute for Intellectual Cooperation of the League of Nations. In the same year, she, together with Víctor Andrés Belaúnde, founded the Institute for the Collection of Ibero-American Classics, which was in charge of disseminating the traditions of the French texts of the most representative books in Latin America.

In Chile, she worked in schools as a teacher of topics such as geography and later reached administrative positions and even the position of director of the Liceo number 6 in Santiago. Already immersed in the world of teaching, she published multiple articles that were disseminated in America and Europe in which her pedagogical philosophy was reflected. Gabriela Mistral was influenced by thinkers like Rodó and Tagore, she believed in outdoor education, in the importance of creating a community among students, mothers, and community workers; she was interested in both child and adult development; she advocated a balance between European and American culture; she promoted the use of the arts in the classroom; and she promoted a religious concept of education as a way to get closer to God. In 1926 she wrote the manuscript "The Image of Christ at School" published by El Mercurio, and even wrote prayers for students to recite before starting the school day.

In December 1927, he wrote an article from Paris advocating for the rights of the child, which would be the following:

- Right to full health, vigor and joy

- Right to professions and professions

- Right to the best of tradition, to the flower of tradition, which in Western peoples is, in my opinion, Christianity

- Right of the child to maternal education

- Right to liberty, the right of the child to free and equal institutions.

- Right of the South American child to be born under decorous laws

- Right to secondary education and other than higher education.

The conception he had about education was fundamental in his writing. As stated by Santiago Sevilla-Vallejo, "She identifies with the woman who cares for children in a maternal and educational sense, where she stressed that, above the formal value of school education, is the sense of trust and humanity that the teacher instills in his students"

Beginnings

The writings written a month before Lucila Godoy arrived in Traiguén in October 1910, are press articles in which she advocated compulsory primary education, with strong criticism of the political world of those years; the social question marked the concern of the intellectuals of the time, in addition to the high expenses incurred for the works and activities of the celebration of the Centennial of Chile; an important sector of the lower town was going through socioeconomic problems and the young Lucila Godoy was no stranger to these problems.

The newspaper El Colono of Traiguén on November 1 published the poem "Sadness", summarizing the feeling of rejection and, in turn, the sentimental tragedy of her frustrated relationship with Romelio Ureta, who he had committed suicide the previous year. In addition, he writes the poem "Rhymes", dated in that city on October 24, 1910, where he expresses sadness at the loss and the impossibility of a farewell. These verses are different from those published with the same title a year earlier.

The same year, Mistral began writing his famous Sonnets of Death. “I was unaware in those years (1910-1911) what the French call the metier de côté, that is, the lateral trade; but one fine day he jumped from myself, because I began to write bad prose, and even lousy, jumping, almost immediately, from it to poetry, which, by paternal blood, was not foreign juice to my body. In the discovery of the second trade the party of my life had begun”. In this period of reflection in Traiguén he opted for poetry as one of his greatest personal achievements.

On December 12, 1914, he won first prize in the Juegos Florales literature contest, organized by the FECh in Santiago, for his Sonnets of Death.

Since then, she has used the literary pseudonym «Gabriela Mistral» in almost all her writings, in homage to two of her favorite poets, the Italian Gabriele D'Annunzio and the Occitan Frédéric Mistral. In 1917, Julio Molina Núñez and Juan Agustín Araya published one of the most important poetic anthologies of Chile, Selva lírica, where Lucila Godoy already appears as one of the great Chilean poets. This post is one of the last in which she uses her real name.

She held the position of inspector at the Liceo de Señoritas de La Serena. In addition, as a prominent educator, she visited Mexico, the United States, and Europe, studying the schools and educational methods of these countries. She was visiting professor at the universities of Barnard, Middlebury and Puerto Rico.

After having lived in Antofagasta in the north of Chile, she worked in Punta Arenas in the extreme south of Chile, where she directed her first high school: Gabriela Mistral had a mission in Punta Arenas: she was sent to one of the southernmost cities of Chile with a specific task, "the Chileanization of a territory where foreigners were overabundant"... The assignment had been made by the Minister of Justice and Public Instruction of the government of Juan Luis Sanfuentes, namely Pedro Aguirre Cerda and for that purpose she had received the position of director of the Sara Brown Girls' High School. Despite having a fundamental role in the Chileanization of the local population, she also lamented the extermination of the Selknam at the same time. The governor of the Magallanes territory, General Luis Alberto Contreras y Sotomayor, transferred her to said southern city to take charge of the Girls' High School No. 1. Her attachment to Punta Arenas was also due to her relationship with Laura Rodig, who lived in that city.

He couldn't stand the polar climate. For this reason, he requested a transfer, and in 1920 he moved to Temuco, from where he left en route to Santiago the following year. During her stay in Araucanía, as director of the Temuco Girls' High School, she met Neftalí Reyes (Pablo Neruda), who recalls that "she made me read the first great names of Russian literature that had such an influence on me." ».

He aspired to a new challenge after having directed two poor quality high schools. She applied for and won the prestigious position of director of Liceo No. 6 in Santiago, but her teachers did not receive her well, reproaching her for her lack of professional studies.

Desolation, considered his first masterpiece, appeared in New York in 1922, published by the Instituto de Las Españas, at the initiative of its director, Federico de Onís. Most of the poems that make up this book he had written ten years ago while he lived in the town of Coquimbito.

On June 23, 1922, in the company of Laura Rodig, she set sail for Mexico on the steamer Orcoma, invited by the then Minister of Education, José Vasconcelos. She stayed there for almost two years, working with the most prominent intellectuals in the Spanish-speaking world.

In 1923, a statue was inaugurated in Mexico and her book Reading for Women was published; the second edition of Desolación appeared in Chile (with a circulation of 20,000 copies) and the anthology Las mejores poesías appeared in Spain, with a prologue by Manuel de Montoliú.

After a tour of the United States and Europe, she returned to Chile, where the political situation was so tense that she was forced to leave again, this time to serve in the old continent as secretary of one of the sections of the League of Nations in 1926; the same year she held the secretariat of the Institute for International Cooperation, of the League of Nations, in Geneva. In December 1925, the Chilean consul general in Sweden, Ambrosio Merino Carvallo, proposed to the government the candidacy of Mistral for the 1926 Nobel Prize in Literature; she would finally get the award 19 years later.

In 1924, he published Tenderness in Madrid, a book in which he practiced an innovative «school poetry», renewing the traditional genres of children's poetry (for example, lullabies, rondas, and lullabies) from an austere and highly refined poetics. Petronila Alcayaga, her mother, died in 1929, for which she dedicated the first part of her book Tala to him.

His life was, from then on, a continuation of the tireless wandering he knew in Chile, without a fixed position in which to use his talent. He preferred, then, to live between America and Europe. Thus, he traveled to Puerto Rico in 1931, as part of a tour of the Caribbean and South America. On this tour, she was named "Benemérita of the National Sovereignty Defense Army" in Nicaragua by General Augusto Sandino, to whom she had given her support in numerous writings. In addition, she gave speeches at the University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras, in Santo Domingo, in Cuba, and in all the other countries of Central America.

Starting in 1933, and for twenty years, he worked as his country's consul in cities in Europe and America. His poetry has been translated into English, French, Italian, German, and Swedish, and has been highly influential in the work of many Latin Americans, such as Pablo Neruda and Octavio Paz.

Nobel Prize

The news that he had won the Nobel was received in 1945 in Petrópolis, the Brazilian city where he had served as consul since 1941 and where in 1943, at the age of 18, Yin Yin (Juan Miguel Godoy Mendoza, his nephew according to official documentation, but that he told Doris Dana, already greatly diminished in her final days, that he was her blood son, whom, with her friend and confidant Palma Guillén, "she had adopted" and with the one who lived at least since he was four years old).

The motivation for giving him this distinction was "his lyrical work, which, inspired by powerful emotions, has made his name a symbol of the idealistic aspirations of the entire Latin American world." He received the Nobel Prize, awarded by the Swedish Academy, on December 10, 1945, in a speech in which he stated: «For a fortune that surpasses me, I am at this moment the direct voice of the poets of my race and the indirect one of the very noble Spanish and Portuguese languages. Both are happy to have been invited to live together in Nordic life, all of it assisted by its ancient folklore and poetry".

At the end of that year he returned to the United States for the fourth time, then as consul in Los Angeles and, with the prize money, bought a house in Santa Barbara. There, the following year, he wrote much of by Lagar I, in many of whose poems the traces of the Second World War can be seen, which would be published in Chile in 1954.

In 1946, he met Doris Dana, an American writer with whom he established a controversial relationship and from whom he would not part until his death.

In New York

Gabriela Mistral was appointed consul in New York in 1953, a position for which she was able to be together with the American writer and graduate Doris Dana, who would later be Mistral's official receiver, spokesperson and executor.

In 1954, she was received with honors at the invitation of the Chilean government headed by Carlos Ibáñez del Campo. On that occasion she was accompanied by Doris Dana, whom the national press identified as "Mistral's secretary”, and that he set foot on Chilean soil for the first and last time.

In Santiago, which had declared a public holiday, the authorities of the capital were waiting for her, while her open-top car was escorted by patrols of carabineros followed by huasos on horseback and prominent schoolchildren from different schools carrying flags. On her way, she passed through a triumphal arch made with fresh flowers in the Alameda with Spain ― " The good sower sows singing ", read on it―; people threw flowers at her. In the afternoon, she was received at La Moneda by President Ibáñez and the next day, she was honored with the title of Doctor Honoris Causa from the University of Chile.

She returned to the United States, a "country with no name," according to her, for whom New York was too cold; he would have preferred to live in Florida or New Orleans (he had sold his property in California), and he told Doris so, to whom he proposed to buy a house in their names in one of those places, but in the end he ended up settling in Long Island, in the Doris Dana family mansion and settled on the outskirts of the megalopolis: "But if you don't want to leave your house, buy me, I repeat, a heater and we'll stay here", he told her. wrote in 1954.

Doris Dana at that time, aware that Mistral's existence was finite, began a meticulous record of every conversation she had with the poet. In addition, she accumulated 250 letters and thousands of literary essays, which constitute the most important Mistralian legacy and which was donated by her niece Doris Atkinson after her death in November 2006.

Death

Mistral had diabetes and heart problems; he had cerebral atherosclerosis, which caused him orientation problems. After having suffered a hemorrhage in his house and following the recommendation of his doctor, Martin Goldfarb, he was admitted to Hempstead General Hospital in New York on December 29, 1956 due to pancreatic cancer; he received extreme unction on January 2, 1957 and two days later he fell into a coma, while on the 8th he received the papal blessing from the priest Renato Poblete. He died at 5:18 on January 10, 1957, at 67 years old; his body was transferred the same day to the Frank Campbell Funeral Home in New York, at the intersection of 81st Street and Madison Avenue, to be embalmed.

On January 12, a requiem mass was held at St. Patrick's Cathedral in New York, presided over by Cardinal Francis Spellman, Archbishop of New York, while the ceremony was officiated by Chilean priest Renato Poblete. The ceremony was attended by around 500 people, including members of the Latin American embassies to the United Nations and members of the Chilean consular corps.

In his will, he stipulated that the money produced from the sale of his books in South America should go to the poor children of Montegrande, where he spent his best childhood years, and that from sales in other parts of the world to Doris Dana and Palma Guillén, who renounced that inheritance for the benefit of poor children in Chile. This request by the poet had not been possible due to Decree 2160, which diverted funds to publishers and intellectuals. This decree was repealed and the income from her work reaches the children of Montegrande in the Elqui Valley.

His remains arrived in Chile on January 18, 1957, aboard a Chilean Air Force plane that landed at Los Cerrillos aerodrome, and were laid to rest at the Central House of the University of Chile where They remained until January 21, the date on which she was buried in the General Cemetery of Santiago.

On March 23, 1960, they were definitively transferred to Montegrande, as was their wish. At 8:00 a.m., the plane that took his remains to the La Florida Aerodrome in La Serena took off from Los Cerrillos Airport, arriving in that city at 10:30 a.m. and from there he was transferred to Vicuña. In the Plaza de Armas, said city, a burning chapel was installed with the body of Mistral from 12:35 p.m. and a response was made. Later the coffin was taken to Montegrande and at 4:45 p.m. she got it on April 7, 1991, on what would have been her 102nd birthday, Fraile Hill was renamed Gabriela Mistral.

Doris Dana remained as executor of Mistral's work and avoided sending it to Chile until the poet was recognized as befitting her worldwide stature. She was even extended an invitation by the government of President Ricardo Lagos, which she declined. Doris Dana's niece, Doris Atkinson, donated Mistral's literary legacy to the Chilean government ―more than 40,000 documents, kept in the archives of the National Library of Chile, including the 250 letters chosen by Zegers for publication―.

Posthumous tributes and legacy

The poet and scholar of her work, Jaime Quezada, has published a series of posthumous books with writings by the Nobel laureate: Escritos políticos (1994), Complete Poems (2001), Bless my language be (2002) and Reunited Prose (2002).

The Organization of American States instituted in 1979 the Inter-American Prize for Culture "Gabriela Mistral", "with the purpose of recognizing those who have contributed to the identification and enrichment of the culture of the Americas and its regions or cultural individualities, either for the expression of its values or for the assimilation and incorporation into it of universal values of culture". It was first awarded in 1984 and last in 2000. In addition, there are a number of other awards and competitions they bear his name.

A private university founded in 1981, one of the first in Chile, also bears her name: the Gabriela Mistral University. In 1977, the Chilean government instituted the Gabriela Mistral Order of Educational and Cultural Merit in her honor.

On November 15, 2005, he received a tribute in the Santiago Metro commemorating the sixty years since he received the Nobel Prize. A boa train upholstered with photographs of the poet was dedicated to her.

Almost all major cities in Chile have a street, square or avenue named after her with her literary name.

In December 2007, much of the material retained in the United States by its first executor, Doris Dana, arrived in Chile. He was received by the Chilean Minister of Culture Paulina Urrutia, together with Doris Atkinson, the new executor. The compilation, transcription and classification has been done by the Chilean humanist Luis Vargas Saavedra who, at the same time, has prepared an edition of the work called Almácigo.

On October 19, 2009, the Diego Portales building was renamed the Gabriela Mistral Cultural Center. The President of the Republic, Michelle Bachelet, enacted Law 20386, published on October 27, 2009, which changed the name of the building to the Gabriela Mistral Cultural Center, "with the purpose of perpetuating her memory and honoring her name and her contribution to the conformation of the cultural heritage of Chile and of Latin American letters".

In 2015, the University of Chile inaugurated the Gabriela Mistral Museum Room, in the Central House of this institution that highlights three milestones in its relationship with the University: The recognition of its quality as a professor in 1923; the creation of the Doctor Honoris Causa degree for her in 1954 (she was the first to receive it); and the wake of her remains in her Hall of Honor in 1957. The room exhibits audiovisual material, paintings, first editions of her works and photos of her.

The Gabriela Mistral Regional Library of La Serena was inaugurated on March 5, 2018 by President Michelle Bachelet, who stressed that it "is harmoniously related to the Casa de Las Palmeras& #34;, a place that the poet bought in 1925 "dreaming of reproducing the Mexican model of rural schools and which today is a fundamental landmark of the Mistral route"».

Numismatics

The image of Mistral has appeared on the 5,000 Chilean peso bill since July 1981. In September 2009, a new bill of the same value was put into circulation with a retouched image of Mistral.

Personal relationships

Gabriela Mistral kept her personal life strictly confidential, which has caused much discussion regarding her personal and sentimental relationships. Mistral remained single throughout her life, a rare occurrence for a woman in her time, so much of her relationships have been interpreted through her literary work or her epistles.

At the age of 15, she had a platonic love affair with Alfredo Videla Pineda, a wealthy man more than 20 years her senior, with whom she corresponded for almost a year and a half.

In 1906, while she was working as a teacher at La Cantera, she met Romelio Ureta, a railway official for whom Gabriela felt great affection. Many scholars of the poet's life have considered Ureta as "the great love" of her life. The relationship had a tragic end when Ureta committed suicide in November 1909. Mistral wrote Sonnets of Death inspired by her feelings after Ureta's death. These verses catapulted her to a national level, after winning the Floral Games of 1914. Although for a time Ureta's death was interpreted as caused by the relationship with Mistral, she herself dismissed it and considered it nothing more than "novelry". Ureta would have committed suicide when he was cornered, after taking money from the railway box where he worked in order to help a friend and not being able to return it.

The Floral Games also served for Gabriela to establish a relationship with the writer Manuel Magallanes Moure, who was sworn in the event. Impressed with Mistral's talent, Magallanes began to send her letters and the epistolary relationship between them became one with deeper feelings. Mistral eliminated a large part of the letters, considering that they could eventually be considered a kind of adultery (since Magallanes was married), but some copies that he kept reflect Mistral's forbidden love for the writer, rejecting his insinuations to set up a meeting..

I love you, Manuel. All my life is concentrated in this thought and in this desire: the kiss I can give and receive from you. And perhaps - surely - I can't give it to you or receive it...! At this moment I feel your affection with such a great intensity that I feel incapable of the sacrifice of having you next to me and not kissing you... I'm dying of love in front of a man who can't caress me...Gabriela Mistral

The letters also reflected Mistral's low self-esteem, considering herself ugly, misshapen, and complicated. "I was born bad, hard of character, enormously selfish and life exacerbated those vices and made me 10 times harsh and cruel." The epistolary relationship lasted almost seven years; Only in 1921 did they meet physically in Santiago, at which point the charm broke and the relationship cooled. The two kept in touch as friends until 1923, when Mistral went abroad. In his farewell letter, Mistral confronted him: "You couldn't love me, my old age, my ugliness... Your pride, very visible, took you away from me."

In 1925, Juan Miguel Godoy, his nephew (son of Carlos, his brother on his father's side) was born. Mistral, who was residing in France at the time, received custody of his nephew and raised him as his own son alongside his Mexican secretary, Palma Guillén. Better known as Yin Yin, he was one of the most influential figures in Mistral's life. His life, however, came to an abrupt end after moving from Europe to Petrópolis, Brazil. Yin Yin could never get used to his new surroundings and was bullied by his classmates. In 1943, he committed suicide at the age of 18 after ingesting arsenic, which was a hard blow for Gabriela Mistral and began one of the darkest times in her life.

Gabriela Mistral and Doris Dana

One of the most controversial issues regarding Mistral, both while she lived and after her death, was associated with her possible lesbianism. In her intimate diaries written between 1945 and 1946, and published in 2002, she rejected her comments about her eventual lesbianism and indicates that it would have been one of the reasons why she moved away from Chile during her last years.

From Chile, not to say. If I've even been hanged by that silly lesbianism, and I'm injured by a captery I can't say. Have you seen such falsehood? [...] There is no desire to return to places in the world where a police novel is made with its own affairs. I am not a reject; neither is an extraordinary thing. I am a woman like any other ChileanGabriela Mistral (ca. 1945), in Blessed be my tongue (edited in 2002).

In the most intimate sphere, there are documents that reflect a very intimate relationship with women. The most debated relationship is the one he had with Doris Dana. The two met in 1949, after communicating via letters since 1948. They remained inseparable until the poet's death in 1957. In her will, Dana was named executor and custodian of the poet's legacy for more than fifty years.

It is the young American —who was 28 years old at the time— who approaches the poet three decades older than her and already consecrated with the Nobel Prize. She writes to him at her residence in Santa Barbara, California. The excuse is the publication of a volume on Thomas Mann that includes a translation by Dana of a text by the Chilean poet. The tone is one of respect, almost veneration:

My dear Teacher:I have taken the liberty of sending you, on behalf of the New Directions Press, the copy intended for you by “The Stature of Thomas Mann”.

Had it been possible, he would have preferred, of course, to enjoy the privilege of putting this book personally into his own hands.

In a period of commercialism, a volume like this is worthy of such grace and dignity.

I write this letter to you to express, within your limits, the deep gratitude I feel for the high privilege of having translated into English your powerful and strong essay, “The other German disaster”

The correspondence between the Chilean poet and the New Yorker is compiled in the book "Niña errante". The volume alone includes about twenty letters written by Doris Dana and more than two hundred from Mistral. Both speak of an attraction at first sight. Throughout the correspondence a passionate relationship is taking shape, capable at times of obsessing the poet.

Less than a year after the correspondence began, Mistral treats her as “love”, identifying herself at times as the masculine gender. She was desperate at times because of Dana's evasive behavior, she who used to go to New York for long periods of time, the city where she was based, sometimes without leaving an address or giving notice.

On April 14, 1949, Mistral wrote to him:

Love: I told you in today's 14th letter that I've been sleeping several nights. I sleep two or three in the morning and seven. But I want to talk to you again today. (I just put a telegram on you. They didn't want to receive the payment of the answer.)I don't understand anything about what happened, my love. I just suspect that my letter about the Artassanchez has made you suffer a lot. And that or that or the plane has caused you a heart damage.

How stupid he loved you most, Doris. Forgive me, my life, forgive me! I won't do it anymore! And thou shalt keep the control of thee, and make faith in thy poor thing, which is a clumsy, vehement, and poisoned by his inferiority complex (age).

Sleep, my love, rest. I'll try to be less brutal and foolish. I owe you the washing of these flaws. I owe you happiness because I have received from you.

At the beginning of the XXI century, research began on the subject of Mistral's lesbianism and her relationship with Dana, who in his later years, he strongly denied having an intimate or sexual relationship with Mistral. American professor Licia Fiol-Matta wrote in A Queer Mother for the Nation: The State and Gabriela Mistral, that Mistral was "a closet lesbian" and that her work contrasted with "her posthumous consecration as a celibate, holy, suffering and heterosexual national icon". These assertions were criticized by the Mistralian environment, while the Gabriela Mistral Foundation denied in 2001 to the writer Juan Pablo Sutherland the inclusion of certain verses of the poet in A corazón abierto, an analysis regarding homosexuality in Chilean literature.

When Dana passed away in 2006, her correspondence with Mistral was made public thanks to permission from Doris Dana's heir, her niece Doris Atkinson. The work Wandering Girl was published in 2009 with a transcription, prologue and notes by Pedro Pablo Zegers, curator of the Writer's Archive of the National Library. In it, some letters that reflect the intimate relationship between the two women are reproduced for the first time, including passionate and spiteful passages.

Doris Dana, 31 years Mistral's junior, explicitly denied in her last interview that her relationship with the writer was romantic or erotic, describing it as a relationship between a stepmother and stepdaughter. Dana denied being a lesbian and in her opinion it is unlikely that Gabriela Mistral was a lesbian.

Since you left I don't laugh and accumulate in the blood I don't know what dense and dark matter. I can't know yet, my love, what happens to me over the sixty days of our separation.

I'm living obsession, love. (...) I didn't know how much that - what I lived - has dug in me, how far I'm burned by that puncture of fire, which hurts just like the coal burning on the palm of the hand.Gabriela Mistral a Doris Dana

As homosexuality has gained acceptance in Chile and more letters reflecting Mistral's work have been released, progress has been made in considering Mistral as a lesbian, and the impact of this on both her work and her legacy. In 2010, the documentary Locas mujeres by María Elena Wood was published, which delved into the relationship between Gabriela Mistral and Doris Dana. It has also been discovered that in 1935 she left her house in Madrid to be used in her meetings by the Sáfico Circle of Madrid, made up of the tribadist writers Victorina Durán, Rosa Chacel, Elena Fortún and Matilde Ras, among others.

In 2015, when the civil union agreement that allowed same-sex couples to be formalized before the Chilean State was promulgated for the first time, President Michelle Bachelet used some verses by Gabriela Mistral to illustrate the progress of the new law. «Our Gabriela Mistral wrote to her beloved Doris Dana: “You have to take care of this, Doris, love is a delicate thing”. And I remember it today because through this law what we do is recognize from the State the care of couples and families and give material and legal support to that relationship born in love, "said Bachelet, which surprised the Gabriela Mistral Foundation.

Awards and distinctions

- 1914: Prize for the Floral Games for "Sounds of Death" (Chile).

- 1945: Nobel Prize in Literature.

- 1946: Chevalier de la Legion de Honor (France).

- 1946: Medalla Enrique José Varona (Cuba).

- 1947: Doctor "honoris causa" by Mills College of Oakland (California).

- 1950: Serra de las Américas Award.

- 1951: Doctor "honoris causa" by Columbia University (New York).

- 1951: Chilean National Literature Award.

Among the many honorary doctorates he received, those from the National University of Guatemala, from California in Los Angeles and from Florence stand out, to name a few, in addition to the one awarded to him by the University of Chile upon his return to his homeland in 1953.

Works

- Sonnets of death (1915). Santiago: Primerose.

- Desolation (1922). New York: Institute of Spain in the United States.

- Readings for women for language teaching (1923), with a prologue of Palma Guillén. Mexico: Editorial Department of the Ministry of Education of Mexico. 1.a edition in Chile, April 2018, Editorial Planeta Sostenible.

- Ternura. Children's Songs: Rounds, Earth Songs, Seasons, Religious, Other Cuna Songs (1923). Madrid: Saturnino Calleja.

- White Clouds: Poetry, and The Prayer of the Teacher (1930). Barcelona: B. Bauza.

- Tala (1938). Buenos Aires: Editorial Sur.

- Anthology (1941), selection of the author. Santiago: Editorial Zig-Zag.

- The Sonnets of Death and Other Elegious Poems (1952). Santiago: Philobiblion.

- Lagar (1954). Santiago: Pacific Editorial.

- Recados, counting on Chile (1957), selection, prologue and notes by Alfonso M. Escudero. Santiago: Pacific Editorial.

Collaborations:

- Ecos (Thursday March 23, 1905) Vicuña: La Voz del Elqui, No. 894

- Page of my soul, dedicated to my mother (Thursday, April 20, 1905) Vicuña: La Voz del Elqui, N° 902

- Of my sorrows, for my sister (Thursday, 13 July 1905) Vicuña: La Voz del Elqui, No. 925

- Black flowers, for the album of Lolo (Thursday, August 10, 1905) Vicuña: La Voz del Elqui, No. 934

- Dreaming (Sunday October 1, 1905) Vicuña: La Voz del Elqui, No. 947

- Voices (Thursday, July 9, 1905) Vicuña: La Voz del Elqui, No. 958

- Intimate letter (Thursday, November 30, 1905) Vicuña: La Voz del Elqui, No. 964

- The instruction of women (Thursday, March 8, 1906) Vicuña: La Voz del Elqui, N°988.

- At the end of life (March 11, 1906) Vicuña: La Voz del Elqui, No. 989.

- Goodbye, Laura. (Thursday, July 5, 1906) Vicuña: La Voz del Elqui, No. 1019.

- Page of an intimate book (September 2, 1906) Vicuña: La Voz del Elqui, No. 1026

- Modern philosophy (Thursday, September 13, 1906) Vicuña: La Voz del Elqui, No. 1029

- Time (September 27, 1906) Vicuña: La Voz del Elqui, No. 1031

- Saetas igneas 1 part (Thursday, 11 October 1906) Vicuña: La Voz del Elqui, No. 1034

- Saetas igneas 2nd part (Sunday October 14, 1906) Vicuña: La Voz del Elqui, No. 1035

- The homeland (Thursday, October 18, 1906) Vicuña: La Voz del Elqui, No. 1036

- Forgotten (November 1, 1906) Vicuña: La Voz del Elqui, No. 1040

- Envy (November 4, 1906) Vicuña: La Voz del Elqui, No. 1041

- Speaks the old experience (Thursday April 1, 1090) Vicuña: La Voz del Elqui, No. 1299

Posthumous editions:

- Desolation, Ternura, Tala and Lagar, compilation of Palma Guillén; Mexico DF: Porrúa, 1957.

- Reasons for San Francisco, selection and prologue of César Díaz-Muñoz Cormatches. Santiago: Editorial del Pacífico, 1965; downloadable from the Portal Memoria Chilena.

- Poem of Chile, text reviewed by Doris Dana; Editorial Pomaire, 1967; downloadable from the portal Memoria Chilena

- Complete poetrywith Esther de Cáceres prologue. Madrid: Aguilar, 1968.

- Magisterium and child, selection of proses and prologue from Roque Esteban Scarpa. Santiago: Editorial Andrés Bello, 1979; downloadable from the Portal Memoria Chilena.

- The praise of the things of the earth, selection and prologue of Roque Esteban Scarpa. Editorial Andrés Bello, 1979.

- Lagar II. Santiago: Editions of the Directorate of Libraries, Archives and Museums (National Library), 1991; downloadable from the Chilean Memory portal.

- Higher anthology, 4 tomos (1: Poetry; 2: Prose; 3: Letters; 4: Life and work), edition and general chronology of Luis Alberto Ganderats. Santiago: Lord Cochrane, 1992.

- Gabriela Mistral in 'La Voz de Elqui'. Santiago: Address of Libraries, Archives and Museums, Gabriela Mistral Museum of Vicuña, 1992; downloadable from the Chilean Memory portal.

- Gabriela Mistral in "El Coquimbo". Santiago: Library Address Archives and Museums, Gabriela Mistral Museum of Vicuña, 1994; downloadable from the Chilean Memory portal.

- Gabriela Mistral: Political writings, selection, prologue and notes by Jaime Quezada. Santiago: Fund for Economic Culture, 1994.

- Complete poetrywith a preliminary study and chronological references of Jaime Quezada. Santiago: Andrés Bello, 2001.

- Bless my tongue. Intimate Journal of Gabriela Mistral (1905-1956), edition of Jaime Quezada. Santiago: Planeta/Ariel, 2002; downloadable from the Portal Memoria Chilena.

- The eye crossed. Correspondence between Gabriela Mistral and the Uruguayan writers, edition, selection and notes by Silvia Guerra and Veronica Zondek. Santiago: LOM, 2005.

- Gabriela Mistral: 50 prosas en "El Mercurio": 1921-1956, prologue and notes by Floridor Pérez. Santiago: El Mercurio/Aguilar, 2005.

- Hard currency. Gabriela Mistral for herselfcompiled by Cecilia García Huidobro. Santiago: Catalonia, 2005.

- This America of ours. Correspondence 1926-1956. Gabriela Mistral and Victoria Ocampo, edition, introduction and notes by Elisabeth Horan and Doris Meyer. Buenos Aires: El Cuenco de Plata, 2007.

- Gabriela Mistral essential. Poetry, prose and correspondence, selection, prologue, chronology and notes of Floridor Pérez. Santiago: Aguilar, 2007.

- Gabriela and Mexico, selection and prologue by Pedro Pablo Zegers. Santiago: International Book Network, 2007.

- Gabriela Mistral. Personal album. Santiago: Address of Libraries, Archives and Museums; Pehuén, 2008.

- Almácigo, unpublished poems; edition of Luis Vargas Saavedra. Santiago: Universidad Católica de Chile, 2009.

- Wrong girl. Letters to Doris Dana, edition and prologue by Pedro Pablo Zegers; Lumen, Santiago, 2009.

- My dear child, edition, selection and prologue by Pedro Pablo Zegers; Dibam/Pehuén, Santiago, 2011.

- American Epistle, correspondence with José Vasconcelos and Radomiro Tomic, in addition to Ciro Alegría, Salvador Allende, Alone, Eduardo Frei Montalva, Pablo Neruda and Ezra Pound, among others; Santiago: Das Kapital Editions, 2012.

- Dance and dream. Rounds and songs of unpublished cradle of Gabriela Mistral, 13 crib songs and 18 unpublished rounds collected by Luis Vargas Saavedra, who discovered them in 2006, when Doris Atkinson invited him to know a series of unpublished manuscripts in South Hadley; Santiago: Catholic University, 2012.

- Walking is sown, unpublished prose, selection of Luis Vargas Saavedra. Santiago: Lumen, 2013.

- Poem of Chile, new version with edition, research and prologue of Diego del Pozo, which adds 59 poems to the 70s that was prepared by Doris Dana in 1967. Santiago: La Pollera, 2013.

- For future humanity, political anthology of Gabriela Mistral. Research, editing and prologue by Diego del Pozo. The book rescues unpublished political texts, as well as others that were not previously compiled, as well as speeches and interviews. Santiago: La Pollera, 2015.

- 70 years of Nobel, citizen anthology, with illustrations by Alejandra Acosta, Karina Cocq, Rodrigo Díaz, Pablo Luebert and Paloma Valdivia; National Council for Culture and Arts (CNCA), 2015 (free and legally rechargeable from CNCA).

- Tropic Sunwith illustrations by the painter Mario Murúa; Planeta Sostenible, 2016.

- Tales & Autobiographies, Unpublished texts revised and compiled by Gladys González. Valparaíso: Editions Cardo Books, 2017.

- Passion of teaching (pedagogical thought), Editorial UV, 2017.

- Manuscripts. Unpublished poetry, 29 unpublished poems revised and compiled by Verónica Jiménez. Santiago: Garceta Editions, 2018.

- Renegades, anthology of 88 poems by writer Lina Meruane, Lumen, Santiago, 2018

- Bless my tongue be: Intimate diary, compiler Jaime Quezada, Catalonia, 2019.

- All guilt is a mystery, mystical and religious anthology of Gabriela Mistral. Research, editing and prologue by Diego del Pozo. The book rescues mystical and religious texts. Santiago: La Pollera, 2020.

- The mysterious maternity of the verse: three lectures. The book collects the lectures delivered by Gabriela Mistral, Alfonsina Storni and Juana de Ibarbourou in Montevideo, in 1938. The introduction is from Lorena Garrido and the postface of Jorge Arbeleche. Santiago: Books of the Vorágine, 2022.

Setting his poems to music

- Where do we knit the round?, album by Charo Cofré, 1985.

- Beloved, hurry the step, album by Angel Parra, 1995.

- Song: The Pajita, version of Javiera Parra, album of Inti-illimani Historic, 2009. 1 album version of Inti-Illimani, 1981.

- My swallow girl.Zinatel's album.

- My swallow girl., Illapu album, 2014.

- Prayer to the Christ of Calvary, musicalized by Cristóbal Fones SJ, from the album Tejido a Tierra: Canto Creyente desde las Entrañas, 2008.

Contenido relacionado

Das Boot (film)

Martin Luis Guzman

Ruben Dario