Gabriel Miro

Gabriel Miró Ferrer (Alicante, July 28, 1879-Madrid, May 27, 1930) was a Spanish writer, usually framed in the so-called generation of 14 or Noucentisme.

Biography

Born in 1879 in Alicante, he was the second son of Encarnación Ferrer and Juan Miró, a Public Works engineer. He studied between 1887 and 1892 together with his brother Juan de él as a boarding student of the Jesuits of the Colegio de Santo Domingo in Orihuela, where he was awarded his first literary prize with a school writing project titled A field day ; there he fell ill with rheumatism in his left knee, perhaps due to hypochondria, and spent a long time in the school infirmary. His delicate state of health prompted his parents to transfer him to the Alicante Institute, and later he went with his family to Ciudad Real, as reflected in his novel Child and Adult ; there he finished high school. In October 1895 he began to study Law at the University of Valencia and at the University of Granada, where he graduated in 1900. Failing in two calls for competitive examinations for the Judiciary, he held modest positions in the Alicante City Council and in its Provincial Council, while living in the secluded neighborhood of Benalúa. In 1908 he won the first prize for a novel organized by El Cuento Semanal, and thus quickly acquired great fame as a storyteller and stylist: that same year several writers paid tribute to him, including Valle Inclán, Pío Baroja and Felipe Trigo; Also in that year his father died. He collaborates with many Spanish and American newspapers and magazines, including Heraldo, Los Lunes de El Imparcial, ABC and El Sol of Madrid, and Caras y Caretas and La Nación of Buenos Aires.

In 1911 he was appointed chronicler of the province of Alicante as well as press officer for the mayor Federico Soto Mollá. Since 1914 he was employed by the Barcelona Provincial Council, where he moved to live. There he directed a Sacred Encyclopedia for the Catalan publishing house Vecchi & amp; Ramos, a project that was not completed but which satisfied him intimately, and between 1914 and 1920 he collaborated in the Barcelona press: Diario de Barcelona , La Vanguardia and Advertising . He also met the editor of many of his novels, Domenech, in the Catalan metropolis. He moved to Madrid when he was appointed in 1920 as an official of the Ministry of Public Instruction and there he remained for the last ten years of his life; in 1921 he was Secretary of the national competitions of that same ministry. In 1925 he won the Mariano de Cavia Award for his article & # 34; Huerto de cruces & # 34; and in 1927 he was nominated for the Royal Spanish Academy, but was not elected, perhaps because of the scandal caused by his novel El obispo leproso, considered anticlerical.[citation required]

His style, very elaborate, is enamelled with traditional words, archaisms and synesthesias. Among his friends, one can mention Óscar Esplá, Emilio Varela and "Azorín", also from Alicante. As well as the Catalan composer Enrique Granados.

Work

Most critics consider that Gabriel Miró's stage of literary maturity began with Las cherries from the cemetery (1910), whose plot develops the tragic love of the hypersensitive young man Félix Valdivia by an older woman (Beatriz) and presents —in an atmosphere of voluptuousness and lyrical intimacy— the themes of eroticism, illness and death.

In 1915 he published El abuelo del rey, a novel that tells the story of three generations in a small Levantine town, to present, not without irony, the struggle between tradition and progress and the environmental pressure; but, above all, we find ourselves with a meditation on time.

One year later Figures of the Lord's Passion (1916-17) appeared, made up of a series of prints about the last days of Christ's life. Also from 1917 is the Libro de Sigüenza, with which Miró began his autobiographical works, focusing on the character of Sigüenza, not only the author's heteronym or alter ego, but his own lyrically fixed self., which gives unity to the scenes in succession that make up the book. El humo dormido (1919), on the theme of time, and Años y leguas (1928), again with the character of Sigüenza as the protagonist, have a similar character. and drive shaft.

In 1921 a book of prints appeared, The angel, the mill, the lighthouse snail, and the novel Our father Saint Daniel, which forms a unit along with El obispo leproso (1926). Both take place in the Levantine city of Oleza, a transcript of Orihuela, in the last third of the 19th century. The city, sunk in lethargy, is seen as a microcosm of mysticism and sensuality, in which the characters are torn between their natural inclinations and the social repression, intolerance and religious obscurantism to which they are subjected.

Ricardo Gullón has described Miró's stories as lyrical novels. They are, therefore, works more attentive to the expression of feelings and sensations than to telling events, in which the following predominate:

- The technique of fragmentation,

- The use of ellipsis and

- The structure of the story in scattered scenes, coupled with reflection and remembrance.

Temporality constitutes the essential theme of the work of the author from Alicante, who incorporates the past into a continuous present, through sensations, evocation and memory. Like, before him, Azorín did. The sensory is also in Miró's literature a form of creation and knowledge, hence:

- The plastic wealth of his work,

- The use of synesthesias and sensory images,

- The surprising adjective

- The most delicious lexicon

These characteristics and themes have traditionally been used to argue that Miró was a stylist, lyricist, or prose poet. This point of view and the use of these labels, however, are not entirely correct, because they lose sight of the narrative tradition from which the author draws. Indeed, in Miró's texts there is a high degree of lyrical-stylistic treatment, which is why he was very influential in the poets of the Generation of '27 (Laín Corona 2010). However, these strategies are not at odds with the use of narrative techniques, as critics have been pointing out more and more (among others, Ian Macdonald, Márquez Villanueva or Lozano Marco, throughout the pages of the studies cited in the bibliography).. In addition, Miró is connected to the Modernism of European authors such as Virginia Woolf, James Joyce and Marcel Proust. According to the parameters of this literary trend, the lyrical and stylistic aspects are not merely decorative or poetic per se, but are incorporated into the novel with narrative functions. This is how Miró also influenced the novelists of the Generation of '27, such as Benjamín Jarnés, Juan Chabás and Carmen Conde (Laín Corona 2013), and later on Francisco Umbral, among other postwar authors (Laín Corona 2014).

Works

Some Complete Works of Gabriel Miró were published twice; in Madrid, 1931, by the "Friends of Gabriel Miró" and in Madrid, 1942, in a single volume, by Biblioteca Nueva. Recently, some Complete Works have appeared in three volumes, edition, introductory studies and bibliography by Miguel Ángel Lozano Marco, Madrid, Castro Library, José Antonio de Castro Foundation, 2006-2008. They include the first two novels and various texts that do not appear in the Biblioteca Nueva edition.

- The woman of Ojeda1901.

- Scenes yarn1903.

- From living1904.

- My friend's novel, Alicante, 1908.

- Nomad1908.

- The broken palm1909

- The holy son1909, short novel

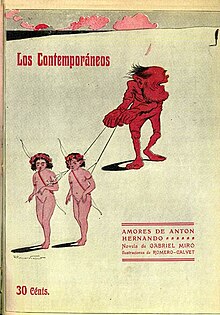

- Loves of Antón Hernando1909, short novel

- The cherries of the cemetery, 1910

- The lady, yours and the others1912, short novel

- From the provincial garden, Barcelona, 1912, stories

- The king's grandfather, Barcelona, 1915.

- Inside the fence, Barcelona, 1916.

- Figures of the Lord's Passion1916 and 1917.

- Book of Sigüenza1917.

- Smoke asleepMadrid, 1919.

- The angel, the mill and the snail of the lighthouse, Madrid, 1921.

- Our father San Daniel, Madrid, 1921.

- Boy and big, Madrid, 1922.

- The leper bishop, Madrid, 1926.

- Years and leagues, Madrid, 1928.

Posthumous editions

- Eagles, Art Editions and Bibliophilia, 1979

- Letters to Alonso Quesada, Editora Regional Canaria, 1985

- Crossing range, Barcelona, Edhasa, 1991

- Levante:Murcia, Barcelona, Lesson Circle, 1993

- Corpus, the snail of the lighthouse and other stories, Alicante, Aguaclara, 1993

- Epistolary, edition of Ian R. Macdonald and Frederic Barberà, 2009.

Author Bibliography

- Guardiola Ortiz, José, Intimate biography of Gabriel Miró. Alicante: Imprenta Guardiola, 1935.

- Ramos, Vicente, The World of Gabriel Miró. Madrid: Gredos, 1964.

- Lopez Landeira, Richard, Gabriel Miró: Trilogy of Sigüenza, Hispanófila Studies, Department of Romance Languages. University of North Carolina, 1972.

- Guillermo Laín Corona, Liberal portrait of Gabriel Miró, Seville, Renaissance, 2015.

- Guillermo Laín Corona. Gabriel Miró’s projections in the Spanish post-war narrativeWoodbridge, Tamesis, 2014.

- Guillermo Laín Corona, "Gabriel Miró and 27. Readings and influences", Revista de Literatura, 72.144 (2010), pp. 397-434. Available online: http://revistadeliteratura.revistas.csic.es/index.php/reviewdeliterature/article/view/240/255

- Guillermo Laín Corona, "Raíces picarescas de la novelística de Gabriel Miró". Speculus. Revista de Estudios Literarios, 42 (2009), s. p. Available online: http://www.ucm.es/info/specculo/numero42/picgmiro.html

- Ian R. Macdonald, Gabriel Miró: His private library and his literary backgroundLondon, Tamesis Books Limited, 1975. Also in Spanish: Gabriel Miró: His personal library and literary circumstancesCome on. Guillermo Laín Corona, Alicante, University of Alicante, 2010.

- Francisco Márquez Villanueva, ed., Harvard University Conference in Honor of Gabriel Miró (1879-1930, Harvard Studies in Romance Language: 39, Department of Romance Languages and Literatures of Harvard University, 1982.

- Francisco Márquez Villanueva, Mironian sphinx and other studies about Gabriel Miró, Alicante, Instituto de Cultura "Juan Gil-Albert", 1990.

- Miguel Angel Lozano Marco and Rosa M.a Monzó, Gabriel Miró: things intact, Canelobre, number 50, autumn 2005.

- Miguel Angel Lozano Marco, ed., New perspectives on Gabriel Miró, Alicante, Universidad de Alicante-Instituto Alicantino de Cultura "Juan Gil-Albert", 2007.

Contenido relacionado

Nahuatl poetry

Song of Roldán

Book of Esther