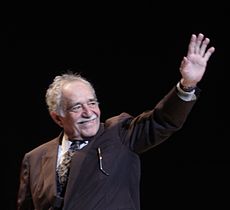

Gabriel Garcia Marquez

Gabriel José de la Concordia García Márquez (Aracataca, 6 March 1927-Mexico City, 17 April 2014) (![]() listen) was a Colombian writer and journalist. Recognized mainly by his novels and stories, he also wrote non-fiction narratives, speeches, storytellings, film reviews and memories. He was known as Gaboand familiarly and by his friends as Gabito. In 1982 he received the Nobel Prize in Literature "for his novels and short stories, in which the fantastic and the real are combined in a world richly composed of imagination, which reflects the life and conflicts of a continent".

listen) was a Colombian writer and journalist. Recognized mainly by his novels and stories, he also wrote non-fiction narratives, speeches, storytellings, film reviews and memories. He was known as Gaboand familiarly and by his friends as Gabito. In 1982 he received the Nobel Prize in Literature "for his novels and short stories, in which the fantastic and the real are combined in a world richly composed of imagination, which reflects the life and conflicts of a continent".

Along with Julio Cortázar, Mario Vargas Llosa and Carlos Fuentes, he is one of the central exponents of the Latin American boom. He is also considered one of the main authors of magical realism, and his best-known work, the novel One Hundred Years of Solitude, is considered one of the most representative of this literary current, and it is even considered that for the success of the novel is that the term is applied to the literature that emerged from 1960 in Latin America. In 2007 the Royal Spanish Academy and the Association of Spanish Language Academies published a popular commemorative edition of this work, for consider it part of the great Hispanic classics of all time.

Biography

Childhood

The son of Eligio García and Luisa Santiaga Márquez Iguarán, he was born in Aracataca, department of Magdalena, Colombia, «on Sunday, March 6, 1927 at nine in the morning...», as the writer himself refers to in his memoirs. When her parents fell in love, Luisa's father, Colonel Nicolás Ricardo Márquez Mejía, opposed that relationship, since Gabriel Eligio, a telegraph operator, was not the man he considered most suitable for his daughter, being the son of a single mother, belonging to the Colombian Conservative Party and being a confessed womanizer.

Intent on separating them, Luisa was sent out of the city, but Gabriel Eligio wooed her with violin serenades, love poems, countless letters, and frequent telegraphic messages. Finally, the family capitulated and Luisa obtained permission to marry Gabriel Eligio, which happened on June 11, 1927 in Santa Marta. The story and tragicomedy of that procession would later inspire her son to write the novel Love in the Time of Cholera.

Shortly after Gabriel's birth, his father became a pharmacist and, in January 1928, moved with Luisa to Barranquilla, leaving Gabriel in Aracataca in the care of his maternal grandparents. Since he lived with them during the first years of his life, he received a strong influence from Colonel Nicolás Márquez, who as a young man killed Medardo Pacheco in a duel and had, in addition to the three official children, another nine with different mothers. The colonel was a Liberal veteran of the Thousand Days War, highly respected by his supporters and known for his refusal to remain silent about the massacre of the banana plantations, an event in which hundreds of people died at the hands of the Colombian Armed Forces during a strike by the banana workers, a fact that García Márquez would capture in his work.

The colonel, whom Gabriel called Papalelo, describing him as his "umbilical cord with history and reality", was also an excellent storyteller and taught him, for example, to frequently consult the dictionary, took him to the circus every year and was the first to introduce his grandson to the "miracle" of ice, which was housed in the United Fruit Company store. He frequently said: "You don't know what a dead man weighs," thus referring to the fact that there was no greater burden than having killed a man, a lesson that García Márquez would later incorporate into his novels.

His grandmother, Tranquilina Iguarán Cotes, was of Galician origin, as stated by Gabo himself on different occasions, whom García Márquez calls grandmother Mina and describes as "an imaginative and superstitious woman" who filled the house with stories of ghosts, premonitions, omens and signs, was as influential on García Márquez as her husband and is even pointed out by the writer as his first and main literary influence, since he was inspired by the original way in which she treated the extraordinary as something perfectly He was a natural when telling stories, and no matter how fantastic or improbable his tales were, he always told them as if they were an irrefutable truth. The writer himself would have stated in an interview in 1983 to the Spanish newspaper El País that:

My interest arose in deciphering its descent, and seeking its own I found mine in the frenetic greens of May to the sea and the fierce rains and the eternal winds of the fields of Galicia. Only then did I understand where the grandmother had brought forth that credulity that allowed her to live in a supernatural world where everything was possible, where rational explanations were completely invalid.

In addition to her style, Grandma Mina also inspired the character of Úrsula Iguarán that, some thirty years later, her grandson would use in One Hundred Years of Solitude, his most popular novel.

His grandfather died in 1936, when Gabriel was eight years old. Due to his grandmother's blindness, he went to live with his parents in Sucre, a town located in the department of the same name in Sucre, where his father worked as a pharmacist.

According to his son Rodrigo, Gabriel had lost vision in the center of his left eye since childhood, when he looked directly at an eclipse.

His childhood is recounted in his memoirs Living to tell it. life and forty since the first publication of One Hundred Years of Solitude.

Education and adulthood

Shortly after arriving in Sucre, it was decided that Gabriel should begin his formal education and he was sent to a boarding school in Barranquilla, a port at the mouth of the Magdalena River. There he acquired a reputation as a shy boy who wrote humorous poems and drew comic strips. Serious and not given to athletic activities, he was nicknamed El Viejo by his classmates.

García Márquez attended the first grades of secondary school at the San José Jesuit school (today the San José Institute) since 1940, where he published his first poems in the school magazine Juventud. Later, thanks to a scholarship granted by the Government, Gabriel was sent to study in Bogotá, from where he was relocated to the Zipaquirá National High School, a city located one hour from the capital, where he will complete his secondary studies.

During his time at the Bogotá house of studies, García Márquez excelled in various sports, becoming captain of the Zipaquirá National High School team in three disciplines: soccer, baseball and athletics.

After graduating in 1947, García Márquez stayed in Bogotá to study Law at the National University of Colombia, where he devoted himself to reading. The Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka “in the false translation of Jorge Luis Borges” was a work that particularly inspired him. He was excited by the idea of writing, not traditional literature, but in a style similar to his grandmother's stories, in which "extraordinary events and anomalies are inserted as if they were simply an aspect of everyday life." His desire to be a writer grew. Shortly after, he published his first short story, La tercera resignación, which appeared on September 13, 1947 in the edition of the newspaper El Espectador.

Although her passion was writing, she pursued a law degree in 1948 to please her parents. After the so-called Bogotazo in 1948, some bloody riots that broke out on April 9 due to the assassination of popular leader Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, the university closed indefinitely and his pension was burned down. García Márquez transferred to the University of Cartagena and began working as a reporter for El Universal. In 1950, he gave up becoming a lawyer to focus on journalism and moved back to Barranquilla to work as a columnist and reporter for the newspaper El Heraldo. Although García Márquez never finished his higher education, some universities, such as Columbia University in New York, have awarded him an honorary doctorate of letters.

Marriage and Family

During his childhood, when he was visiting his parents in Sucre, he met Mercedes Barcha, also the daughter of an apothecary, at a student dance and immediately decided that he had to marry her when he finished his studies. Indeed, García Márquez married in March 1958 in the church of Nuestra Señora del Perpetuo Socorro in Barranquilla with Mercedes "to whom he had proposed marriage since he was thirteen years old".

Mercedes is described by one of the writer's biographers as "a tall, pretty woman with shoulder-length brown hair, the granddaughter of an Egyptian immigrant, apparently manifested in high cheekbones and large, piercing brown eyes." And García Márquez has referred to Mercedes constantly and with proud affection; when he spoke of her friendship with Fidel Castro, for example, he observed, "Fidel trusts Mercedes even more than he trusts me."

In 1959 they had their first son, Rodrigo, who became a filmmaker, and in 1961 they settled in New York, where he worked as a correspondent for Prensa Latina. After receiving threats and criticism from the CIA and Cuban dissidents, who did not share the content of his reports, he decided to move to Mexico and they settled in the capital. Three years later, their second son was born, Gonzalo, currently a graphic designer in the Mexican capital.

Although García Márquez had residences in Paris, Bogotá and Cartagena de Indias, he lived most of the time in his house in Mexico City, where he established his residence in the early 1960s and where he wrote One Hundred years of solitude at number 19 La Palma street in the San Ángel neighborhood.

Fame

García Márquez's worldwide notoriety began when One Hundred Years of Solitude was published in June 1967 and sold 8,000 copies in one week. From then on, success was assured and the novel sold a new edition every week, going on to sell half a million copies in three years. It was translated into more than twenty-five languages and won six international awards. Success had finally arrived and the writer was 40 years old when the world learned his name. From the fan correspondence, awards, interviews and appearances it was obvious that his life had changed. In 1969, the novel won the Chianciano Appreciate in Italy and was named the "Best Foreign Book" in France.

In 1970, it was published in English and was chosen as one of the 12 best books of the year in the United States. Two years later he was awarded the Rómulo Gallegos Prize and the Neustadt Prize and in 1971, Mario Vargas Llosa published a book about his life and work, entitled García Márquez: history of a deicide . To contradict all this display, García Márquez simply returned to writing. Determined to write about a dictator, he moved with his family to Barcelona (Spain) spending his last years under the regime of Francisco Franco.

The popularity of his writing also led to friendships with powerful leaders, including former Cuban President Fidel Castro, a friendship that has been explored in Gabo and Fidel: Portrait of a Friendship. In an interview with Claudia Dreifus in 1982, she says that her relationship with Castro is fundamentally based on literature: "Ours is an intellectual friendship. It may not be widely known that Fidel is a cultured man. When we're together, we talk a lot about literature."

Some have criticized García Márquez for this relationship; the Cuban writer Reinaldo Arenas, in his 1992 memoirs Before Night Falls, points out that García Márquez was with Castro, in 1980 in a speech in which the latter accused the recently murdered refugees at the embassy of Peru of being "rabble". Arenas bitterly remembers the writer's colleagues honoring Castro with "hypocritical applause" for this.

Also due to his fame and his views on US imperialism, he was labeled a subversive and for many years was denied a US visa by immigration authorities. However, after Bill Clinton was Elected president of the United States, he finally lifted his travel ban to his country and stated that One Hundred Years of Solitude "is his favorite novel".

In 1981, the year he was awarded the French Legion of Honor, he returned to Colombia from a visit with Castro, only to find himself in trouble once more. The government of liberal Julio César Turbay Ayala accused him of financing the M-19 guerrilla group. Fleeing from Colombia, he requested asylum in Mexico, where until his death he will continue to maintain a home.

From 1986 to 1988, García Márquez lived and worked in Mexico City, Havana, and Cartagena de Indias. In 1987, there was a celebration in America and Europe of the twentieth anniversary of the first edition of One Hundred Years of Solitude. He had not only written books, he had also ended up writing his first play, Love Rant Against a Seated Man. In 1988 the film A very old man with enormous wings was released, directed by Fernando Birri, an adaptation of the short story of the same name.

In 1995, the Caro y Cuervo Institute published in two volumes the Critical Repertoire on Gabriel García Márquez.

In 1996 García Márquez published Noticia de un kidnapping, where he combined the testimonial orientation of journalism and his own narrative style. This story represents the immense wave of violence and kidnappings that Colombia continued to face.

In 1999, American Jon Lee Anderson published a revealing book about García Márquez, for which he had the opportunity to spend several months with the writer and his wife in their home in Bogotá.

Illness and death

In 1999 he was diagnosed with lymphatic cancer. In this regard, the writer declared in an interview in 2000 to El Tiempo de Bogotá:

A few years ago I was subjected to a three-month treatment against a lymphoma, and today I am surprised by the enormous lottery that has been that stumble in my life. For the fear of not having time to finish the three volumes of my memories and two short stories books, I reduced to a minimum the relationships with my friends, unconnected the phone, canceled the travels and all kinds of pending and future commitments, and locked myself to write every day without interruption from 8am to 2pm. During that time, without any medicines of any kind, my relationships with the doctors were reduced to annual controls and a simple diet so as not to pass on weight. In the meantime, I returned to journalism, returned to my favorite vice of music and I got up to date on my backward readings.

In the same interview, García Márquez refers to the poem entitled La marioneta, which was attributed to him by the Peruvian newspaper La República as a farewell for his imminent death, denying such information. He denied being the author of the poem and clarified that "the true author is a young Mexican ventriloquist who wrote it for his doll," referring to the Mexican Johnny Welch.

In 2002, his biographer Gerald Martin flew to Mexico City to speak with García Márquez. His wife, Mercedes, had the flu and the writer had to visit Martin at his hotel. As he said, Gabriel García Márquez no longer had the appearance of the typical cancer survivor. Still thin and with short hair, he completed Live to Tell It that year.

At the beginning of July 2012, due to comments from his brother Jaime, it was rumored that the writer suffered from senile dementia, but a video in which he celebrated his birthday in March 2012 served to deny the rumor.

In April 2014, he was admitted to the National Institute of Medical Sciences and Nutrition, in Mexico City, due to a relapse due to lymphatic cancer that was diagnosed in 1999. The cancer had affected a lung, lymph nodes, and liver. García Márquez died on April 17, 2014. Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos noted that the writer was "the Colombian who, in the entire history of our country, has carried the name of the homeland further and higher.", decreeing three days of national mourning for his death. His ashes rest in the cloister of La Merced in Cartagena de Indias, where they were transferred on May 22, 2016.

Literary career

Journalist

García Márquez began his career as a journalist while studying law at university. In 1948 and 1949 he wrote for the Cartagena newspaper El Universal. From 1950 to 1952, he wrote a "whimsical" column under the pseudonym "Septimus" for the local newspaper El Heraldo de Barranquilla. García Márquez took note of his time in El Heraldo . During this time he became an active member of the informal group of writers and journalists known as the Barranquilla Group, an association that was a great motivation and inspiration for his literary career. He worked with figures such as José Félix Fuenmayor, Ramón Vinyes, Alfonso Fuenmayor, Álvaro Cepeda Samudio, Germán Vargas, Alejandro Obregón, Orlando Rivera "Figurita" and Julio Mario Santo Domingo, among others. García Márquez would use, for example, Ramón Vinyes, who would be represented as a "Catalan wise man", owner of a bookstore in One Hundred Years of Solitude.

At this time, García Márquez read the works of writers such as Virginia Woolf and William Faulkner, who influenced his narrative techniques, historical themes, and use of provincial locations. The Barranquilla environment provided García Márquez with a world-class literary education and a unique perspective on Caribbean culture. Regarding his journalism career, Gabriel García Márquez has mentioned that it served as a tool for him to "not lose touch with reality" .

At the request of Álvaro Mutis in 1954, García Márquez returned to Bogotá to work at El Espectador as a reporter and film critic. A year later, García Márquez published in the same newspaper Relato de un náufrago, a series of fourteen chronicles about the shipwreck of the destroyer A. R. C. Caldas, based on interviews with Luis Alejandro Velasco, a young sailor who survived the shipwreck.

The publication of the articles led to a nationwide public controversy when the last writing revealed the hidden story, as it discredited the official version of events that had attributed the cause of the shipwreck to a storm. As a consequence of this controversy, García Márquez was sent to Paris to be a foreign correspondent for El Espectador. He wrote about his experiences in El Independiente , a newspaper that briefly replaced El Espectador , during the military government of General Gustavo Rojas Pinilla and was later closed by the Colombian authorities. Shortly after, after the triumph of the Cuban revolution in 1960, García Márquez traveled to Havana, where he worked at the press agency created by the Cuban government Prensa Latina and became friends with Ernesto Guevara.

In 1974, García Márquez, together with leftist intellectuals and journalists, founded Alternativa, which lasted until 1980 and marked a milestone in the history of opposition journalism in Colombia. For the first issue, García Márquez wrote an exclusive article on the bombing of the La Moneda Palace during the 1973 Chilean Coup, which guaranteed a sell-out. He would then be the only one who would sign the articles.

In 1994, together with his brother Jaime García Márquez and Jaime Abello Banfi, Gabriel García Márquez created the Fundación Nuevo Periodismo Iberoamericano (FNPI), which aims to help young journalists learn from teachers like Alma Guillermoprieto and Jon Lee Anderson, and stimulate new ways of doing journalism. The entity's headquarters are in Cartagena de Indias and García Márquez was the president until his death.In his honor, the FNPI created the Gabriel García Márquez Journalism Award, which has been awarded since 2013 to the best of Ibero-American journalism.

First and main publications

Her first story, La tercera resignación, was published in 1947 in the newspaper El Espectador. A year later, he began his journalism job for the same newspaper. His first works were all short stories published in the same newspaper from 1947 to 1952. During these years he published a total of fifteen short stories.

Gabriel García Márquez wanted to be a journalist and write novels; he also wanted to create a more just society. For La hojarasca, his first novel, it took him several years to find a publisher. It was finally published in 1955, and although the reviews were excellent, most of the edition remained in storage and the author received "not one penny in royalties" from anyone. García Márquez points out that "of everything he had written, La hojarasca was his favorite because they considered it the most sincere and spontaneous."

Gabriel García Márquez took eighteen months to write One Hundred Years of Solitude. On Tuesday, May 30, 1967, the first edition of the novel went on sale in Buenos Aires. Three decades later it had been translated into 37 languages and sold 25 million copies worldwide. «It was a real bombshell, which exploded from the first day. The book was released to bookstores without any kind of advertising campaign, the novel sold out its first edition of 8,000 copies in two weeks and soon turned the title and its magical realism into a mirror of the Latin American soul." One Hundred Years of Solitude has influenced nearly every major novelist throughout the world. The novel chronicles the Buendía family in the town of Macondo, which was founded by José Arcadio Buendía. It can be considered a work of magical realism.

Love in the Time of Cholera was first published in 1985. It is based on the stories of two couples. The story of the young couple formed by Fermina Daza and Florentino Ariza is inspired by the love story of García Márquez's parents. However, as García Márquez explains in an interview: «The only difference is that my parents got married. And as soon as they were married, they were no longer interesting as literary figures." The love of the elderly is based on a story he read in a newspaper about the death of two Americans, almost eighty years old, who met every year in Acapulco. They were on a boat and one day they were killed by the boatman with his oars. García Márquez notes: “Through her death, the story of their secret romance became known. I was fascinated with her. They were each married to someone else."

Latest works

In 2003, García Márquez published the memoir Vivir para contarla, the first of three volumes of his memoirs, which the writer had announced as:

It begins with the life of my maternal grandparents and the love of my father and my mother in the early century, and ends in 1955 when I published my first book, The leafletuntil travelling to Europe as correspondent The Spectator. The second volume will continue until the publication Hundred years of solitudeMore than twenty years later. The third will have a different format, and it will only be the memories of my personal relationships with six or seven presidents of different countries.

The novel Memory of my sad whores appeared in 2004 and is a love story that follows the romance of a ninety-year-old man and his pubescent concubine. This book caused controversy in Iran, where it was banned after 5,000 copies were printed and sold. In Mexico, an NGO threatened to sue the writer for advocating child prostitution.

Style

Although there are certain aspects that readers can almost always expect to find in García Márquez's work, such as humor, there is no clear, predetermined, template style. In an interview with Marlise Simons, García Márquez noted:

In each book I try to take a different path [...]. One doesn't choose the style. You can investigate and try to discover what is the best style for a theme. But the style is determined by the subject, by the mood of the moment. If you try to use something that is not convenient, it will hardly work. So the critics build theories around this and see things that I had not seen. I respond only to our lifestyle, the life of the Caribbean.

García Márquez is also known for leaving out seemingly important details and events in such a way that the reader is forced to play a more participative role in the unfolding story. For example, in The colonel has no one to write to him the main characters are not given names. This practice is influenced by Greek tragedies, such as Antigone and Oedipus the King, in which important events occur outside of the performance and are left to the audience's imagination.

Most Important Issues

Loneliness

The theme of loneliness runs through a large part of García Márquez's works. Pelayo observes that «Love in the Times of Cholera, like all the works of Gabriel García Márquez, explores the loneliness of the person and of the human species... a portrait through the loneliness of love and to be in love".

Plinio Apuleyo Mendoza asked him: «If loneliness is the theme of all your books, where should we look for the roots of this excess? In his childhood perhaps? ». García Márquez replied: «I think it is a problem that everyone has. Every person has their own way and the means of expressing it. Feeling permeates the work of so many writers, though some of them may express the unconscious."

In his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, The loneliness of Latin America, he refers to this issue of loneliness related to Latin America: «The interpretation of our reality with foreign schemes only contributes to make ourselves more and more unknown, less and less free, more and more lonely."

Macondo

Another important theme in García Márquez's work is the invention of the village he calls Macondo. He uses his hometown of Aracataca as a geographical reference to create this imaginary city, but the representation of the town is not limited to this specific area. García Márquez shares: "Macondo is not so much a place as a state of mind."

This fictional town has become notoriously well known in the literary world and "its geography and inhabitants are constantly invoked by professors, politicians and agents" [...] making it "hard to believe that it is a pure invention". In La Hojarasca, García Márquez describes the reality of the "banana boom" in Macondo, which includes an apparent period of "great wealth" during the presence of US companies, and a period of depression with the exit of US companies related to bananas. In addition, One Hundred Years of Solitude takes place in Macondo and tells the complete story of this fictional city from its founding to its disappearance with the last Buendia.

In his autobiography, García Márquez explains his fascination with the word and the concept of Macondo when he describes a trip he took with his mother back to Aracataca:

The train stopped at a station that had no city, and a while later passed the only banana plantation (plátano) along the route that had its name written at the door: Macondo. This word has attracted my attention from the first trips I had made with my grandfather, but I have only discovered as an adult that I liked his poetic resonance. I've never heard of it, and I don't even wonder what it means... it happened to me when I read in an encyclopedia that's a tropical ceiba tree."

According to some scholars, Macondo—the city founded by José Arcadio Buendía in One Hundred Years of Solitude—only exists as a result of language. The creation of Macondo is totally conditioned to the existence of the written word. In the word —as an instrument of communication— reality is manifested, and allows man to achieve a union with circumstances independent of his immediate environment.

Violence and culture

In several of García Márquez's works, including The Colonel Has No One to Write to Him, La mala hora, and La hojarasca, there are subtle references to "La Violencia," a civil war between conservatives and liberals that lasted until the 1960s, causing the deaths of several hundred thousand Colombians. They are references to unfair situations that various characters experience, such as curfew or press censorship. La mala hora, which is not one of García Márquez's most famous novels, stands out for its representation of violence with a fragmented image of the social disintegration it causes. It can be said that in these works "violence becomes a story, through the apparent uselessness (or use) of so many episodes of blood and death".

However, although García Márquez describes the corrupt nature and injustices of that time of violence in Colombia, he refuses to use his work as a platform for political propaganda. "For him, the duty of the revolutionary writer is to write well, and the ideal is a novel that moves the reader for its political and social content, and at the same time for its power to penetrate reality and expose its other face."

In the works of García Márquez one can also find an "obsession with capturing Latin American cultural identity and particularizing the features of the Caribbean world". Likewise, he tries to deconstruct the established social norms in this part of the world. As an example, the character of Meme in One Hundred Years of Solitude can be seen as a tool to criticize the conventions and prejudices of society. In this case, she does not conform to the conventional law that "young women must arrive virgins at marriage" because she has had an illicit relationship with Mauricio Babilonia. Another example of this criticism of social norms can be seen through the love relationship between Petra Cotes and Aureliano Segundo. At the end of the play—when the protagonists are old—they fall more deeply in love than before. Thus, García Márquez is criticizing the image shown by society that "old people cannot love".

Literary Influences

In his youth, by associating with the Barranquilla group, Gabriel García Márquez began to read the work of Ernest Hemingway, James Joyce, Virginia Woolf and, most importantly, William Faulkner from whom he received a transcendental influence explicitly recognized by himself when in his Nobel Prize reception speech he mentions: "my teacher William Faulkner". Faulkner-like elements appear such as deliberate ambiguity and an early depiction of loneliness.

He also undertook a study of the classical works, finding enormous inspiration in the work of Sophocles' Oedipus the King of whom, on many occasions, Gabriel García Márquez has expressed his admiration for his tragedies and uses a quote from Antígona at the beginning of her work La hojarasca whose structure has also been said to be influenced by Antigone's moral dilemma.

In an interview with Juan Gustavo Cobo Borda in 1981, García Márquez confessed that the iconoclastic poetic movement called "Stone and Heaven" (1939) was fundamental for him, stating that:

The truth is that if it had not been for "Piedra and Heaven", I am not very sure that I became a writer. Thanks to this heresy I was able to leave behind an arched rhetoric, so typically Colombian... I believe that the historical importance of "Piedra and Heaven" is very great and not sufficiently recognized... There I learned not only a system of metaphor, but what is more decisive, an enthusiasm and a novelty for poetry that I yearn for every day and that produces an immense nostalgia.

Magical realism

As an author of fiction, García Márquez is always associated with magical realism. In fact, he is considered, together with the Guatemalan Miguel Ángel Asturias, a central figure in this genre. Magical realism is used to describe elements that have, as is the case in the works of this author, the juxtaposition of fantasy and myth with daily and ordinary activities.

Realism is an important theme in all of García Márquez's works. He said that his first works (with the exception of La hojarasca), such as The colonel has no one to write to him, La mala hora and Big Mama's Funerals reflect the reality of life in Colombia and this theme determines the rational structure of the books. He says: "I do not regret having written them, but they belong to a type of premeditated literature that offers a vision of reality that is too static and exclusive."

In his other works he has experimented more with less traditional approaches to reality, so that "the most terrible, the most unusual is said with an impassive expression". A commonly cited example is a character's spiritual and physical ascension into heaven while hanging his clothes to dry, in One Hundred Years of Solitude. The style of these works is inscribed in the concept of the "marvellous real" described by the Cuban writer Alejo Carpentier and has been labeled magical realism.

Literary critic Michael Bell proposes an alternative interpretation for García Márquez's style, as the category of magical realism has been criticized for being dichotomizing and exoticizing: "What is really at stake is a psychological flexibility that is capable of sentimentally inhabiting the daytime world while remaining open to the incitements of those domains that modern culture has, by its own internal logic, necessarily marginalized or repressed". García Márquez and his friend Plinio Apuleyo Mendoza discuss his work in a similar way, «The treatment of reality in your books...has received a name, magical realism. I have the impression that your European readers tend to notice the magic of the things you tell, but they don't see the reality that inspires them. Probably because their rationalism prevents them from seeing that reality does not end in the price of tomatoes or eggs."

García Márquez creates a world so similar to everyday life but at the same time totally different from it. Technically, he is a realist in presenting the true and the unreal. Somehow he deftly deals with a reality in which the boundaries between the true and the fantastic fade very naturally.

García Márquez considers that imagination is nothing more than an instrument for the elaboration of reality and that a novel is the encrypted representation of reality and to the question of whether everything he writes has a real basis, he has answered:

There is no line in my novels that is not based on reality.

Awards, recognitions and tributes

- Nobel Prize. García Márquez received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1982, according to the laudatory of the Swedish Academy, "for his novels and short stories, in which the fantastic and the real are combined in a quiet world of rich imagination, reflecting the life and conflicts of a continent".

His acceptance speech was titled The loneliness of Latin America. He was the first Colombian and the fourth Latin American to win a Nobel Prize in Literature, after which he declared: «I have the impression that when giving me the prize they have taken into account the literature of the subcontinent and they have awarded me as a form of award. of the entirety of this literature.

García Márquez has received many other awards, distinctions and tributes for his works, such as those mentioned below:

- First Prize in the contest of the Association of Writers and Artists, for his story One day after Saturday (1955).

- ESSO Novel Award for Bad time (1961).

- Doctor Honoris causa of Columbia University in New York (1971).

- Neustadt International Prize for Literature (1972).

- Premio Rómulo Gallegos Hundred years of solitude (1972).

- Jorge Dimitrov Prize for Peace (1979).

- Medal of the Legion of Honour of France in Paris (1981).

- Aguila Azteca decoration in Mexico (1982).

- Forty-year Award for the Journalists Circle of Bogotá (1985).

- Honorary member of the Instituto Caro y Cuervo in Bogotá (1993).

- Museum: On March 25, 2010, the Colombian government finished rebuilding the house in which García Márquez was born in Aracataca, because he had been demolished forty years ago, and inaugurated in it a museum dedicated to his memory with more than fourteen environments that recreate the spaces in which his childhood passed.

- In the East of Los Angeles (California), in the municipality of Las Rozas de Madrid and in Zaragoza (Spain) there are streets that bear their name.

- In Bogota, Mexico's Economic Culture Fund built a cultural centre named after it, opened on January 30, 2008.[6]

- In 2015, the Bank of the Republic of Colombia announced a new series of bills where its image will appear, more precisely in the $50.000 pesos ticket that will start its circulation in 2016.

| Predecessor: Elias Canetti | Nobel Prize in Literature 1982 | Successor: William Golding |

Legacy and criticism

García Márquez is an important part of the Latin American literary boom. His works have received numerous critical studies, some extensive and significant, that examine the subject matter and its political and historical content. Other studies focus on the mythical content, the characterizations of the characters, the social environment, the mythical structure or the symbolic representations in his most notable works.

While García Márquez's works attract a number of critics, many scholars praise his style and creativity. For example, Pablo Neruda wrote of One Hundred Years of Solitude that "it is the greatest revelation in the Spanish language since Cervantes's Don Quixote".

Some critics argue that García Márquez lacks adequate experience in the literary arena and that he only writes from his personal experiences and imagination. In this way, they say that his works should not be significant. In response to this, García Márquez has mentioned that he agrees that sometimes his inspiration does not come from books, but from music. However, according to Carlos Fuentes, García Márquez has achieved one of the greatest characteristics of modern fiction.

This is the liberation of time, through the liberation of an instant from the moment that allows the human person to recreate himself and his time. Despite everything, no one can deny that García Márquez has helped to rejuvenate, reformulate and recontextualize literature and criticism in Colombia and the rest of Latin America. To the east of the Atlántico Cervantes, to the west García Márquez, two bastions captured the deep reality of their moment and left an enchanted vision of a world undreamed of, on the surface of the earth.

Rejection from The New Yorker magazine.

Gabriel García Márquez rose to international fame after publishing One Hundred Years of Solitude at the end of the 1960s. In the 1970s he focused on one of his major projects, the magazine Alternativa, which until its closure in 1980 marked a milestone in the history of Colombian opposition journalism. At that time, Gabo was already a well-known and famous writer, but (small) failures were part of his life, like any other. In 1981, he sent one of his writings to The New Yorker, but the American magazine refused to publish it, according to a letter now on display at the Harry Ransom Center, a library and museum at the University of Texas at Austin.

Roger Angell, one of the editors of The New Yorker, explains in a 1982 letter why the text would not be published: "The story has the usual brilliance of his writing, but in our way To think about, his resolution does not make the reader accept his bold and beautiful conception." In 1982, just a few months later, Gabo was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Political activity

Militancy and ideology

In 1983, when Gabriel García Márquez was asked: «Are you a communist?» the writer replied, “Of course not. I am not and never have been. Nor have I been part of any political party." García Márquez told his friend Plinio Apuleyo Mendoza: "I want the world to be socialist and I believe that sooner or later it will be." According to Ángel Esteban and Stéphanie Panichelli, "Gabo understands by socialism a system of progress, freedom and relative equality" where knowledge is, in addition to a right, a left (there is a play on words that both authors use to title the chapter of their book: "If knowing is not a right, surely it will be a left"). García Márquez traveled to many socialist countries such as Poland, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, the Soviet Union, Hungary, and later wrote some articles, showing his "disagreement with what was happening there". In 1971, in an interview for the magazine "Libre" (which he sponsored) he declared: "I continue to believe that socialism is a real possibility, that it is the good solution for Latin America, and that we must have a more active militancy."

In 1959, García Márquez was a correspondent in Bogotá for the Prensa Latina press agency created by the Cuban government after the beginning of the Cuban revolution to report on events in Cuba. There “he had to report objectively on the Colombian reality and at the same time disseminate news about Cuba and his job consisted of writing and sending news to Havana. It was the first time that García Márquez did truly political journalism." Later, in 1960, he founded with his friend Plinio Apuleyo Mendoza a political magazine, Acción Liberal , which went bankrupt after publishing three issues..

Friendship with Fidel Castro

Gabriel García Márquez met Fidel Castro in January 1959 but their friendship was formed later, when García Márquez was working with Prensa Latina, living in Havana and they saw each other again several times. After meeting Castro, «Gabo was convinced that the Cuban leader was different from the caudillos, heroes, dictators or scoundrels that had swarmed through the history of Latin America since the 19th century, and he sensed that only through him would this revolution, still young, it could reap fruits in the rest of the American countries".

According to Panichelli and Esteban, "exercising power is one of the most comforting pleasures that man can feel", and they think that this is the case with García Márquez "until a mature age". For this reason, the friendship between García Márquez and Castro has been questioned and whether it is a result of García Márquez's admiration for power.

Jorge Ricardo Masetti, an Argentine ex-guerrilla and journalist, thinks that Gabriel García Márquez "is a man who likes to be in the kitchen of power".

In the opinion of César Leante, García Márquez has something of an obsession with the Latin American caudillos. He also says that «García Márquez's unconditional support for Fidel Castro falls largely within the psychoanalytic field [...] which is the admiration that the Patriarch's breeder has felt, always and disproportionately, for the Latin American caudillos that emerged from the montoneras. For example, Colonel Aureliano Buendía, but above all the unnamed Caribbean dictator who, like Fidel Castro, grows old in power». Leante says that García Márquez "is considered in Cuba as a kind of minister of culture, head of cinematography and ambassador plenipotentiary, not from the Ministry of Foreign Relations, but directly from Castro, who employs him for delicate and confidential missions that he does not entrust to his diplomacy".

Juan Luis Cebrián has called Gabriel García Márquez "a political messenger", due to his articles.

According to the British Gerald Martin, who published the first authorized biography of the novelist in 2008, García Márquez feels an "enormous fascination with power." He points out that "He has always wanted to be a witness to power and it is fair to say that this fascination is not free, but pursues certain objectives" and mentions that many consider his proximity to Cuban leader Fidel Castro excessive. Martin recalls that he was also related with Felipe González (former president of the Spanish Government) or with Bill Clinton (former president of the United States) but "everyone only looks at his relationship with Castro".

On the other hand, the diplomat, journalist, biographer and friend of the Nobel Prize, Plinio Apuleyo Mendoza points out that «He is a friend of Castro, but I don't think he is a supporter of the system, because we visited the communist world and we were very disappointed».

Mediations and political support

García Márquez participated as a mediator in the peace talks between the National Liberation Army (ELN) and the Colombian government that took place in Cuba and between the government of Belisario Betancourt and the group Movimiento 19 de abril (M-19); He also participated in the peace process between the Andrés Pastrana government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) guerrilla, which nevertheless failed.

In 2006, García Márquez joined the list of prominent Latin American figures such as Pablo Armando Fernández, Ernesto Sabato, Mario Benedetti, Eduardo Galeano, Thiago de Mello, Frei Betto, Carlos Monsiváis, Pablo Milanés, Ana Lydia Vega, Mayra Montero and Luis Rafael Sánchez who support the independence of Puerto Rico, through their adherence to the "Proclamation of Panama" unanimously approved at the Latin American and Caribbean Congress for the Independence of Puerto Rico, held in Panama in November 2006.

Politics in his work

Politics play an important role in the works of García Márquez, in which he uses representations of various types of societies with different political forms to present their opinions and beliefs with concrete examples, even if they are fictional examples. This diversity of ways in which García Márquez represents political power is a sample of the importance of politics in his works. A conclusion that can be derived from his works is that "politics can extend beyond or beyond the proper institutions of political power."

For example, in his work One Hundred Years of Solitude we have the representation of a place «where there is not yet a consolidated political power and there is, therefore, no law in the sense of a voted precept by Congress and sanctioned by the president, which regulates the relations between men, between them and the public power and the constitution and operation of this power".In contrast, the representation of the political system in The Autumn of the Patriarch is that of a dictatorship, in which the leader is grotesque, corrupt and bloodthirsty and with such great power that he ever asked what time it is and they had answered what you ordered, my general.

One of García Márquez's first novels, La mala hora, may be a reference to the dictatorship of Gustavo Rojas Pinilla and depicts political tension and oppression in a rural town, whose inhabitants aspire to to liberty and justice but without success in achieving either.

Works

Novels

- The leaflet (1955)

- The colonel has no one to write (1961)

- Bad time (1962)

- Hundred years of solitude (1967)

- The Fall of the Patriarch (1975)

- Chronicle of an announced death (1981)

- Love in the times of wrath (1985)

- The general in his maze (1989)

- Of love and other demons (1994)

- Memory of my sad sluts (2004)

Stories

- The Funerals of Big Mom (1962)

- The unbelievable and sad story of the Eréndira Candida and her desailing grandmother (1972)

- Blue dog eyes (1972, compilation of his first stories)

- Twelve pilgrim tales (1992)

Non-fiction narrative

- Report of a shipwreck (1970)

- The Adventure of Miguel Littín clandestine in Chile (1986)

- News of a kidnapping (1996)

Journalism

- When I was happy and undocumented (1973)

- Chile, the coup and the gringos (1974)

- Chronicles and reports (1976)

- Traveling through socialist countries (1978). It was republished by Penguin Random House in 2015 under the title Travel to Eastern Europe.

- militant journalism (1978)

- Journalistic work 1. Costume Texts (1948-1952) (1981)

- Journalistic work 2. Between cachacos (1954-1955) (1982)

- Journalistic work 3. Europe and America (1955-1960) (1983)

- The loneliness of Latin America. Writings on Art and Literature 1948-1984 (1990)

- First reports (1990)

- Journalistic work 5. Press releases (1961-1984) (1991). The first edition included notes from 1980 to 1984; the 1999 edition was added a note from 1961, a note from 1966, three from 1977 and one from 1979.

- Journalistic work 4. For free (1974-1995) (1999)

- Unfinished lover and other press texts (2000). Selection of notes published in the journal Change.

- Gabo journalist (2013). Panoramic of his journalistic work craved and commented by several of his colleagues.

- Gabo. The nostalgia of bitter almonds (2014). Notes and answers to readers published in the journal Change.

- Gabo answers (2015). Answers to the readers of the magazine Change.

- The scandal of the century (2018). Edition and selection of Christopher Pera and prologue of Jon Lee Anderson.

Memories

- Living to tell (2002)

Theater

- Diamond of love against a man sitting (1994)

Speech

- Our First Nobel Prize (1983)

- The Loneliness of Latin America / Brindis for Poetry (1983)

- The Cataclysm of Damocles (1986)

- A manual to be a child (1995)

- For a country within reach of children (1996)

- A hundred years of solitude and a tribute (2007), with Carlos Fuentes.

- I don't come to say a speech. (2010)

Cinema

- Viva Sandino (1982). Guion. Also published as The assault (1983) and Kidnapping (1984).

- How to tell a story (1995). Workshop.

- I rent to dream (1995). Workshop.

- The blessed mania of counting (1998). Workshop.

Interviews

- García Márquez talks about García Márquez in 33 major reports (1979). Compilation and prologue of Alfonso Rentería Mantilla

- The smell of guava (1982). With Plinio Apuleyo Mendoza.

- Protagonists of Hispanic American Literature (1985). With Emmanuel Carballo.

- Texts annexed to Gabriel García Márquez. The spell haunted (2005). With Yves Billon and Mauricio Martínez Cavard. Full version of the interview presented in the documentary The spell haunted (1998).

- To keep the wind from taking them (2011). Collection and prologue by Fernando Jaramillo

- Treatments and portraits (2013). With Silvia Lemus. Transcription of the television interview that Lemus conducted to García Márquez in Cartagena in 1992.

Dialogue

- The novel in Latin America. Dialogue (1968). With Mario Vargas Llosa. Transcription of the lecture held by both writers at the National University of Engineering, in Lima, on 5 and 7 September 1967. There are Peruvian editions of 1968, 1991, 2003, 2013 and 2017. Alfaguara launched the book in 2021 under the name Two loneliness. A dialogue on the novel in Latin America.

Books about García Márquez

Biographies

- Garcia Marquez. The journey to the seed (1997) of Dasso Saldívar. Alphaguara.

- Gabriel García Márquez. A life (Gabriel García Márquez. A Life, 2008), by Gerald Martin. Spanish translation: Debate, 2009.

- Gabriel García Márquez. Life, Magic and Work of a Global Writer (2021), by Alvaro Santana Acuña. El Equilibrista/Fundación para las Letras Mexicanas.

Testimonials

- «The Lost Case», in The flame and the ice (1984), Plinio Apuleyo Mendoza. Text also published as low book titles Those times with Gabo (2000) and, expanded with letters, Gabo. Letters and memories (2013).

- Los García Márquez (1996) by Silvia Galvis.

- Solitude and company. A vocal portrait of Gabriel García Márquez (2014), by Silvana Paternostro.

- Gabo and mercede. A goodbye (2021), by Rodrigo García.

- Gabo + 8 (2021), by Guillermo Angulo.

Essays

- «Gabriel García Márquez o la cord», en Ours (1966) by Luis Harss.

- García Márquez: History of a Deicide (1971), by Mario Vargas Llosa.

- After the keys of Melquíades (2001), by Eligio García Márquez.

- Gabo and Fidel. The landscape of a friendship (2004) by Angel Esteban and Stéphanie Panichelli.

Comics

- García Márquez for beginners (2007), by Mariana Solanet (text) and Héctor Luis Bergandi (ilustrations).

On screen

García Márquez professed a particular interest in film and television, participating as a screenwriter, patron and allowing his work to be adapted. Already in his youth in Barranquilla, together with the painter Enrique Grau, the writer Álvaro Cepeda Samudio and the photographer Nereo López, he participated in the making of the surrealist short film La langosta azul (1954).

Later, in the fifties, he studied film at the Centro Sperimentale Di Cinematografia in Rome, having as classmates the Argentine Fernando Birri and the Cuban Julio García Espinosa, who would later be considered founders of the so-called Fundación del Nuevo Latin American cinema. These three personalities have repeatedly declared the impact that watching the film Miracle in Milan by Vittorio de Sica had on them, as well as witnessing the birth of Italian neorealism, a trend that made them envision the possibility of make films in Latin America following the same techniques. It should be noted that this stay in Rome served for the writer to learn several of the ins and outs of filmmaking, as long as he shared long hours of work on the moviola alongside screenwriter Cesare Zavattini. This individual sharpened in García Márquez a cinematographic precision when it came to narrating with images, which he would later use as part of his work in Mexico City. García Márquez has chaired the New Latin American Cinema Foundation since 1986, which is based in Havana.

It is known that many Mexican cinematographic works of the 1960s were written by García Márquez, who, like many intellectuals of the time, signed the scripts with a pseudonym. In any case, El gallo de oro (1964), by Roberto Gavaldón, and Tiempo de morir (1966), by Arturo Ripstein, are memorable. The first, based on the homonymous short story by Juan Rulfo, co-written with the author himself and fellow Mexican writer Carlos Fuentes, starred Ignacio López Tarso, Narciso Busquets and Lucha Villa, and was photographed by the famous Gabriel Figueroa. The second, a western initially filmed by Ripstein, had its sequel almost twenty years later under the tutelage of Jorge Alí Triana.

In addition to the three films mentioned, between 1965 and 1985, García Márquez participated directly as a screenwriter in the following films: In this town there are no thieves (1965), by Alberto Isaac; Dangerous Game (segment "HO") (1966), by Luis Alcoriza and Arturo Ripstein; Patsy, my love (1968), by Manuel Michel; Presagio (1974), by Luis Alcoriza; La viuda de Montiel (1979), by Miguel Littín; María de mi corazón (1979), by Jaime Humberto Hermosillo; The Year of the Plague (1979), by Felipe Cazals (adaptation of Daniel Defoe's book The Plague Diary), and Eréndira (1983), by Ruy Guerra.

In 1975 R.T.I. Televisión de Colombia produces the television series La mala hora directed by Bernardo Romero Pereiro, based on the homonymous novel by García Márquez and broadcast in 1977.

In 1986, together with his two classmates from the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografía, and supported by the Committee of Latin American Filmmakers, he founded the San Antonio de Los Baños International Film and Television School in Cuba, an institution to which he will dedicate time and money from his own pocket to support and finance the film career of young people from Latin America, the Caribbean, Asia and Africa. As of the following year, in said center he will dedicate himself to giving the workshop "How to tell a story", the result of which come innumerable audiovisual projects, in addition to several books on dramaturgy.

In 1987, Francesco Rosi directed the adaptation of Chronicle of a Death Foretold, starring Rupert Everett, Ornella Muti, Gian Maria Volonté, Irene Papas, Lucía Bosé and Anthony Delon.

In 1988 the following were produced and exhibited: A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings, by Fernando Birri, with Daisy Granados, Asdrúbal Meléndez and Luis Ramírez; Miracle in Rome, by Lisandro Duque Naranjo, with Frank Ramírez and Amalia Duque García; Fable of the Beautiful Palomera, by Ruy Guerra, with Claudia Ohana and Ney Latorraca, and Letters from the Park, by Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, with Ivón López, Víctor Laplace, Miguel Paneque and Mirta Ibarra.

In 1990, García Márquez traveled to Japan, stopping in New York to meet the contemporary director whose scripts he most admires: Woody Allen. The reason for his trip to the eastern country is to meet Akira Kurosawa, at that time filming Akira Kurosawa's Dreams, interested in bringing the story of The Patriarch's Autumn to the big screen. , set in medieval Japan. Kurosawa's idea was totalizing, embedding the entire novel on celluloid regardless of the footage; unfortunately, for this idea there was no possibility of financing, and the project remained at that.

In 1991, Colombian television produced María, the novel by Jorge Isaacs, adapted by García Márquez along with Lisandro Duque Naranjo and Manuel Arias.

In 1996 Edipo Alcalde was presented, an adaptation of Oedipus the King by Sophocles made by García Márquez and Estela Malagón, directed by Jorge Alí Triana, and starring Jorge Perugorría, Angela Molina and Paco Rabal.

In 1999, Arturo Ripstein films There's No One to Write to The Colonel, starring Fernando Luján, Marisa Paredes, Salma Hayek and Rafael Inclán.

In 2001 The Invisible Children by Lisandro Duque Naranjo appeared.

In 2006 Love in the Time of Cholera was filmed, with a script by South African Ronald Harwood and directed by British director Mike Newell. Filmed in Cartagena de Indias, the characters are played by Javier Bardem, Giovanna Mezzogiorno, John Leguizamo, Catalina Sandino and Benjamin Bratt.

In March 2010, and within the framework of the Cartagena International Film Festival, the film version of Del amor y otros demonios was released, a co-production between Colombia and Costa Rica directed by the Costa Rican Hilda Gentleman.

Memory of my sad whores, a co-production between Denmark and Mexico, directed by the Danish Henning Carlsen and with the film adaptation by the French Jean-Claude Carrière was to be filmed in 2009 at the state of Puebla, but it was suspended due to financing problems, apparently due to a controversy motivated by the issue due to the threat of a lawsuit from an NGO describing the novel and the script as an apology for child prostitution and pedophilia. Finally, the film was secretly filmed in the city of San Francisco de Campeche (Mexico) in 2011, starring Emilio Echevarría and released in 2012.

At the theater

García Márquez made little direct inroads into theater, as only the monologue Diatribe of love against a seated man is known, staged for the first time in 1988 in Buenos Aires and re-released in 1994 at the Teatro Nacional de Bogota.

His work in the theater has mostly been adaptations of his novels. In 1991, Juan Carlos Moyano adapted and directed a street theater and public square show called Memoria y olvido de Úrsula Iguarán, based on the novel One Hundred Years of Solitude, which presented at the 1991 Manizales International Theater Festival and at the 1992 Ibero-American Theater Festival in Bogotá. In 2000, Jorge Alí Triana premiered the theatrical version of Chronicle of a Death Foretold, adaptation of the homonymous novel, with great national and international success.

Equally, the work of García Márquez has been adapted to the genre of opera:

- Florence in the Amazon (1991), opera with a libretto by Marcela Fuentes-Berain placed in a music metro by Daniel Catán based on motives of the novel Love in the times of wrath.

- Eréndira (1992), opera with music by Violeta Dinescu based on the story The unbelievable and sad story of the Eréndira Candida and her desailing grandmother.

- Love and other demons (2008), opera with a libretto by Kornél Hamvai placed in music subway by Péter Eötvös, based on the novel Of love and other demons.

García Márquez in fiction

- In the novel Cartagena (2015), by Claudia Amengual, García Márquez appears as a character in his last years of life.

- The teacher and the Nobel (2015), novel by Beatriz Parga, recreates the relationship between a five-year-old García Márquez and her teacher, Rosa Fergusson.

Contenido relacionado

The Godfather (film)

Julio Cortazar

Maria Teresa Leon