Francisco Morazan

José Francisco Morazán Quesada (Tegucigalpa, October 3, 1792 – San José, Costa Rica, September 15, 1842) was a Honduran soldier and politician who ruled the Federal Republic of Central America during the turbulent period from 1830 to 1839.

He rose to fame after his victory at the Battle of La Trinidad on November 11, 1827. From then until his defeat in Guatemala in 1840, Morazán dominated the political and military scene of Central America.

In the political arena, Francisco Morazán was recognized by members of his party as a great thinker and visionary. According to liberal writers like Federico Hernández de León Lorenzo Montúfar and Ramón Rosa Morazán he tried to transform Central America into a great and progressive nation; while conservative writers like Manuel Coronado Aguilar accuse him of trying to impose himself by force for personal reasons; finally, socialist writers like Severo Martínez Peláez suggest that the liberals led by Morazán were the criollo landowners who had been exploited by the criollos. Guatemalans and the regular clergy during the colony and, with Morazán at the head, intended to seize power in the region for themselves. Morazán's management as president of the Federal Republic promulgated liberal reforms, which were aimed at removing power to the main members of the conservative party: the criollos who resided in Nueva Guatemala de la Asunción and the regular orders of the Catholic Church. The reforms included: education, freedom of the press and religion among others. He further limited the power of the secular clergy of the Catholic Church by abolishing the tithe by the government and separating church and state.

With these reforms, Morazán made powerful enemies, and his term in office was marked by bitter infighting between liberals and conservatives. However, through his military capacity, Morazán remained firmly in power until 1837, when the Federal Republic irrevocably fractured. This was exploited by the regular orders of the Church and the Guatemalan conservative leaders, who united under the leadership of the Guatemalan General Rafael Carrera, and, in order not to allow the liberal criollos to take away their privileges, ended up dividing the Central America in five states.

Biography

Early Years and Education

José Francisco Morazán Quesada was born on October 3, 1792 in Tegucigalpa, then part of the Intendancy of Comayagua, Captaincy General of Guatemala, during the last years of Spanish rule. His parents were José Eusebio Morazán Alemán and Guadalupe Quesada Borjas, both members of an upper-class Creole family dedicated to commerce and agriculture. His grandparents were: Juan Bautista Morazán, a Corsican emigrant, and María Gertrudis Alemán. Thirteen days after his birth, Morazán was baptized in the church of San Miguel Arcángel, by Father Juan Francisco Márquez.

| 4. Juan Bautista Morazzani (Italian) | ||||||||||||||||

| 2. José Eusebio Morazán German (1761-?) | ||||||||||||||||

| 10. Francisco Antonio Alemán | ||||||||||||||||

| 5. Maria Gertrudis German | ||||||||||||||||

| 11. Agueda Alemán | ||||||||||||||||

| 1. José Francisco Morazán Quesada | ||||||||||||||||

| 6. John the Baptist of Quesada | ||||||||||||||||

| 3. Guadalupe Quesada Borjas | ||||||||||||||||

| 7. María Borjas Alvarenga | ||||||||||||||||

Francisco Morazán was for the most part a self-taught man. In 1804, his parents took advantage of the opening of a Catholic school in the town of San Francisco where they sent the young José Francisco, although the length of time he remained in that place is unknown. According to the Honduran historian and liberal intellectual Ramón Rosa, Morazán «had the misfortune of being born [...] in that sad time of isolation and total darkness in which Honduras lacked schools. [...] Morazán, then, had to learn his first letters, reading, writing, the elementary rules of Arithmetic in private schools of terrible organization and sustained with a kind of contribution that parents prepared ». The teachings he received were through Fray Santiago Gabrielino, appointed religious instructor to the Guatemalan priest José Antonio Murga.

In 1808, José Francisco moved with his family to Morocelí, El Paraíso (The Paradise). There he worked on the land inherited by Don Eusebio Morazán. In addition, he had the opportunity to work as an employee of the mayor's office. In 1813 the family moved to Tegucigalpa. Once there, Mr. Eusebio placed his son under the tutorship of León Vásquez, who taught her civil law, criminal proceedings, and notaries. At the same time, he had the opportunity to learn to read French in the library of his uncle-in-law, Dionisio de Herrera, which allowed him to become familiar with the works of Montesquieu, the social contract of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the French Revolution, history of Europe, as well as biographies of Greek and Roman leaders. This dedication and spirit of improvement led José Francisco from time to time to stand out in his hometown, where he came to represent the interests of some people before the colonial court.

On August 7, 1820, Narciso Mallol would have Licenciado Dionisio de Herrera as secretary of the Mayor of Tegucigalpa, and a year later he would have the services of the young Francisco Morazán who would act as secretary of the city council and later as defender ex officio in civil and criminal proceedings.

Marriage and Family

Francisco Morazán married María Josefa Lastiri in the Cathedral of Comayagua on December 30, 1825. From this marriage he was born in San Salvador,

Adela Morazán Lastiri in 1838: Morazán's only daughter. María Josefa belonged to one of the richest families in the province of Honduras. Her father was the Spanish merchant Juan Miguel Lastiri, who played an important role in the commercial development of Tegucigalpa. Her mother was Margarita Lozano, a member of a powerful Creole family in the city. María Josefa was a widow who had first married the landowner Esteban Travieso, with whom she had 4 children. On her death, Lastiri inherited a fortune. María Josefa's inheritance and the new circle of powerful and influential friends, who came out of this marriage, greatly helped to boost Morazán's own businesses, and consequently his political projects.

Out of their marriage, Francisco Morazán fathered a son, Francisco Morazán Moncada, who was born on October 4, 1827 from the general's relationship with Francisca de Moncada, daughter of a well-known Nicaraguan politician named Liberato Moncada. Francisco Morazán Jr. lived in the house of the Morazán-Lastiri couple, and accompanied his father in Guatemala, El Salvador, Panama, Peru and finally in Costa Rica. After the death of his father, Francisco Morazán Moncada settled in Chinandega (Nicaragua), where he dedicated himself to agriculture. He died in 1904, at 77 years of age. General Morazán also had an adoptive son named José Antonio Ruiz. He was the legitimate son of Eusebio Ruiz and the Guatemalan lady Rita Zelayandía, who handed over her son to General Morazán, when the boy was only 14 years old. José Antonio accompanied his adoptive father in various military actions and became a brigadier general. He died in Tegucigalpa in 1883.

Beginnings of his political and military career

The Captaincy General of Guatemala gained independence from Spain in 1821. It was then that Francisco Morazán began to take an active part in politics. He worked in the Tegucigalpa city hall, where he served as secretary to Mayor Narciso Mallol and as public defender in civil and criminal court cases, among other things. This allowed Morazán to acquire a great knowledge of the structure and functioning of the public administration of the province. This also allowed him to come into close contact with the problems of colonial society.

On November 28, 1821, a note from General Agustín de Iturbide arrived in Guatemala suggesting that the Kingdom of Guatemala, and the Viceroyalty of Mexico, form a great empire under the Plan of Iguala and the Treaties of Córdoba. The Advisory Provisional Board stated that this was not an immediate order to make such a determination, but rather an option; so it was necessary to explore the will and listen to the opinion of the people of Central America. With this idea, open town hall meetings were held in different parts of the Kingdom, since the new form of government had to be decided by the congress that would meet in 1822.

The question of the annexation to Mexico caused divisions within each of the provinces since some cities were in favor of it and others were against it. In Honduras, for example, Comayagua - through its governor José Tinoco de Contreras - declared itself in favor of annexation; but Tegucigalpa, the second most important city in the province, was opposed to the idea of it. This caused Tinoco to take repressive actions against the authorities of that city. Faced with this situation, an army of volunteers was organized in Tegucigalpa in order to counteract Tinoco's aggressiveness and defend his independence. It was during these events that Francisco Morazán enlisted as a volunteer, at the service of the Tegucigalpa authorities. He was designated as captain of one of the companies, by decision of the official leaders who organized the militias. Thus began Morazán's military life and his fight against conservative interests.

Tegucigalpa, however, could not maintain its opposition, and was forced to recognize its annexation to Mexico on August 22, 1822. Agustín de Iturbide's annexation to the Mexican Empire did not last long, because he abdicated on March 19 of 1823, and the 1st. On July of that same year, Central America proclaimed its final independence, and became the United Provinces of Central America. Subsequently, on September 25, 1824, Francisco Morazán was appointed secretary general of the government of his uncle by marriage and first head of state of Honduras, Dionisio Herrera, and signed the first constitution of that country. Then, on April 6, 1826, he was named president of the Representative Council.

Background of the Federal Republic

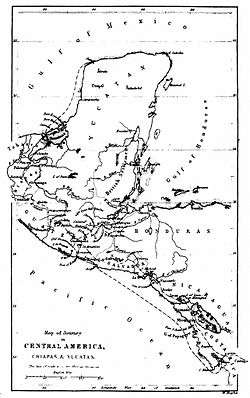

After the independence of Central America from Spain in 1821, and its subsequent absolute emancipation on July 1, 1823, the Central American nation was finally free and independent. This new nation was renamed the United Provinces of Central America, and was made up of the states of Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica. The following year, the Constituent Congress met in Guatemala City with the objective of deciding what would be the system of government through which the destinies of the young nation would be governed. Two different proposals were presented at the discussion table:

- Liberals bet for a federalist government, influenced by the United States Constitution (from 1787) and Cadiz (from 1812). This type of government gave each State greater independence or autonomy to administer and to create its own laws and reforms, among other things; but always under the supervision of the Federal Government, guarantor of a Constitution.

- The conservatives, on the other hand, bowed down by a centralist government. Through this system, they wanted a single control and administration center. In this system, decisions and laws were adopted in the capital of the nation and apply to all other states alike.

- After discussing the two proposals, the Liberals, who were a majority, asserted this advantage and won the right to adopt the 'federalist thesis', in the face of the discontent of the conservatives.

Later, on November 22, 1824, under the motto "God, Union and Liberty", the Constitution was approved and the nation was renamed the Federal Republic of Central America. Under the new Constitution, Manuel José Arce was elected president of the Liberal Party, who promised to transform the Central American economy and society through his liberal reforms, but after a few months Arce found great opposition from the conservatives, who, due to their social influence and enormous economic power, did not allow any type of progress in their government programs. Convinced of his limitations, Arce ended up abandoning his government programs and decided to ally with the opposition party. This new position by Arce gave the conservatives almost complete control of the federal government.

In 1826, Dr. Miguel Echarri who for reasons of internal politics had been expelled from Colombia and had settled in Honduras, took the opportunity to initiate the young Francisco Morazán and Dionisio de Herrera (who served as supreme head of Honduras).

Coup d'état in Honduras of 1827

The Federal Government headed by Manuel José Arce intended to dissolve the Federal Congress, and therefore called a meeting to be held in Cojutepeque on October 10, 1826, to elect an extraordinary Congress. This unconstitutional measure was rejected by the Honduran head of state, Dionisio de Herrera.

Manuel José Arce dissolved the Congress and the Senate in October 1826 trying to establish a centralist or unitary system by allying with the conservatives, for which reason he was left without the support of his party, the liberals. As a result, there was a conflict between the Federal Government and the States, ruling against Dionisio de Herrera and Mariano Prado, head of the State of El Salvador.

Arce came into conflict with Dionisio de Herrera for which the National Assembly called for new elections in Honduras, but Herrera ignored this decree since according to the Honduran constitution his term expired until September 16, 1827. Arce decided to expel Herrera for these reasons, but under the pretext of protecting the tobacco plantations in Los Llanos (Santa Rosa de Copán), owned by the federal government. Arce commissioned Lieutenant General Justo Milla to execute the coup, who on April 9, 1827 and commanding 200 men, seized Comayagua —the state capital—, captured Herrera and sent him to a prison in Guatemala.

While Milla was busy consolidating power in Comayagua, Morazán escaped from federal troops. He left the besieged capital in the company of Colonels Remigio Díaz and José Antonio Márquez, with the purpose of obtaining reinforcements in Tegucigalpa. His plan was to return and liberate the state capital. Upon his return from Tegucigalpa, he and his 300-man army stationed themselves at the La Maradiaga ranch, where they engaged Milla's forces on April 29, 1827. Following the battle, Milla seized power in Honduras (August 10). May) and Morazán fled to Choluteca. Later he traveled to Ojojona, where he met his family in June. There he was imprisoned for 23 days and transferred to Tegucigalpa by order of Commander Ramón de Anguiano.

He left on bail and went to La Unión (El Salvador) in June 1827, with the intention of emigrating to Mexico. In this town, he met Mariano Vidaurre, a special envoy from El Salvador to Nicaragua. Vidaurre convinced Morazán that, in that country, he could find the military support he needed to expel Milla from Honduran territory. Francisco Morazán traveled to the city of León (Nicaragua) on September 15, where he met with the commander of arms of the State of Nicaragua, Colonel José Anacleto Ordóñez known as Cleto Ordóñez. For Morazán, the meeting paid off, as the Nicaraguan leader provided him with weapons and a contingent of 135 men. These militiamen were joined by Salvadoran troops led by Colonel José Zepeda, and some columns of Honduran volunteers in Choluteca (Honduras).

Provisional Head of State of Honduras

Morazán headed with his troops towards southern Honduras, arriving in Choluteca in October 1827. When Justo Milla discovered Morazán's presence, he quickly moved with his troops to Tegucigalpa, where he established his headquarters. For his part, Morazán went to Sabanagrande. At 9 in the morning on November 11, Morazán and his men faced the army of Colonel Justo Milla, in the memorable Battle of La Trinidad. After five hours of heavy fighting, Milla's federal troops were crushed by Morazán's men, Milla and some of his officers survived and fled the battlefield. Following this victory, Morazán marched to Comayagua where he made his triumphal entry on November 26. The next day he convened the Representative Council, which appointed him provisionally head of state, and appointed Diego Vigil as deputy head.

He sent pacification columns to the north coast and border towns, and put down an uprising in Opoteca. On June 28, 1828, he deposited the headquarters of the State in Vigil, to participate in the Central American civil war.

Central American Civil War

After his victory at 'La Trinidad,' Morazán emerged as the leader of the liberal movement and became recognized for his military skills throughout Central America. For these reasons, he received calls for help from liberals in El Salvador. As in Honduras, Salvadorans opposed the new congressmen and other government officials elected by the decree issued on October 10, 1826. Salvadorans demanded the reinstatement of former political leaders, but President Manuel Arce argued that this measure was necessary to restore constitutional order.

In March 1827 the government of El Salvador responded with military force. Salvadoran troops marched towards Guatemala with the intention of taking the capital of the Republic and removing the president from his chair. But President Arce himself took command of his federal troops and defeated the Salvadorans at dawn on March 23 in Arrazola. The Salvadoran division was dispersed and the leaders fled. The camp was littered with corpses, prisoners, weapons, ammunition and luggage. After these events, President Arce ordered 2,000 federal troops under the command of General Manuel de Arzú to occupy El Salvador. This event marked the beginning of the civil war.

Meanwhile in Honduras, Francisco Morazán accepted the challenge proposed by the Salvadorans. He handed over command to Diego Vigil as the new Honduran head of state and went to Texiguat, where he prepared and organized his troops for the Salvadoran military campaign. In June 1828, Morazán headed for El Salvador with a force of 1,400 men. This group of militants was made up of small groups of Hondurans, Nicaraguans, and Salvadorans who brought their own tools of war. They also had the support of the Indians who served as infantry. Some volunteers followed their liberal convictions, others worked for a political leader, others simply hoped to get something in return for their efforts after the war was over.

While the Salvadoran army engaged federal forces in San Salvador, Morazán positioned himself in the eastern part of the state. On July 6, Morazán defeated Colonel Vicente Domínguez's troops at the El Gualcho hacienda. In his memoirs, Morazán describes the battle as follows:

At 12 p.m. I started my march with this object, but the rain did not allow me to double the day, and I was forced to wait, in the Treasury of Gualcho, to improve the time... At three o'clock in the morning, that the water ceased, I put two hunter companies in the height that dominates the hacienda, to the left... At five I knew the position that this (the enemy) occupied. I couldn't go back in these circumstances... It was no longer possible to continue the march, without grave danger, by an immense plain and by the very presence of the opposites. Less could defend me at the hacienda, placed under a height of more than 200 feet that in the form of a semi-circle dominates the main building, cut by the opposite end with an inaccessible river that serves as a pit. It was, therefore, necessary to accept the battle with all the advantages that the enemy had attained... I made the hunters advance over the enemy to stop their movement, because, knowing the criticalness of my position, I was marching on them in step of attack. In the meantime, the force went up a narrow and slope, and the fire broke in half a shot of a rifle, which then became general. But 175 bison soldiers made repeated attacks of all the bulk of the enemy impotent for a quarter of an hour... The enthusiasm that produced in all the soldiers the heroism of these brave Hondurans exceeded the number of opposites. When the action became general on both sides, it was forced to reverse our right wing. And occupied the light artillery that supported it; but the reserve, working then on that side, re-established our line, recovered the artillery and decided the action, rolling part of the center and all the left flank, which dragged, in their escape, the rest of the enemy, then dispersed in the plain... The auxiliary Salvadorans, who shortened their march to the noise of the action, with the desire to take it, arrived in time to pursue the dispersed...

Morazán kept fighting around San Miguel, defeating every platoon sent by General Arzú from San Salvador. This motivated Arzú to leave Colonel Montúfar in charge of San Salvador and take care of Morazán personally. When the liberal leader became aware of Arzú's movements, he left for Honduras to recruit more troops, joining the Écija Militia. On September 20, General Arzú was near the Lempa River with 500 men in search of Morazán, when he learned that his forces had capitulated in Mejicanos and San Salvador.

Meanwhile, Morazán left for El Salvador with an army of 600 men, and stationed himself in Goascorán on October 2, 1828. General Arzú feigning illness returned to Guatemala, leaving his troops under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Antonio from Aycinena. The colonel and his troops were marching towards Honduran territory, when they were intercepted by Morazán's men in San Antonio. On October 9, Aycinena was forced to surrender. With the capitulation of San Antonio, El Salvador was finally free of federal troops. On October 23, General Morazán made his triumphal entry into the Plaza de San Salvador. He returned to Honduras with news of an uprising in Olancho, where he addressed a proclamation to its inhabitants on November 22, 1828. He then marched on Ahuachapán, to organize the army with a view to the liberation of Guatemalan territory and to restore constitutional order..

Battles and dictatorship in Guatemala

On January 1, 1829, Morazán set up a barracks in Ahuachapán and did everything possible to organize a large army, which he called the Allied Army Protector of the Law. He asked the government of El Salvador to provide him with 4,000 men, but he had to settle for 2,000. When he was in a position to act in January 1829, he sent a division under Colonel Juan Prem to enter Guatemalan territory and take control of Chiquimula. The order was carried out by Prem despite the resistance offered by the enemy. Shortly thereafter, Morazán moved the Écija militia near Guatemala City under the command of Colonel Gutiérrez to force the enemy out of their trenches and cause his troops to desert. Meanwhile, Colonel Domínguez, who had left Guatemala City with six hundred infantry to attack Prem, learned of the small force Gutiérrez counted. Domínguez changed his plans and Gutiérrez went after him. This opportunity was seized by Prem who moved from Zacapa and attacked Domínguez's forces, defeating them on January 15, 1829. After these events, Morazán ordered Prem to continue his march with the 1,400 men under his command and occupy the post of San José, near the capital.

Meanwhile, the people of Antigua Guatemala organized against the Guatemalan government and placed the department of Sacatepéquez under the protection of General Morazán. This hastened Morazán's invasion of Guatemala, who stationed his men in the town of Pínula, near the capital city. Military operations in the capital began with small skirmishes in front of the government fortifications. On February 15, one of Morazán's largest divisions, under the command of Cayetano de la Cerda, was defeated at Mixco by federal troops.

Because of this defeat, Morazán lifted the siege of the city and concentrated his forces in Antigua. A division of federal troops had followed him from the capital under the command of Colonel Pacheco, in the direction of Sumpango and El Tejar with the purpose of attacking him in Antigua. But Pacheco extended his forces, leaving some of them in Sumpango. When he arrived at San Miguelito on March 6, with a smaller army, he was defeated by General Morazán. This incident once again raised the morale of Morazán's men. After the victory at San Miguelito, Morazán's army, made up of militiamen from Écija, increased with the union of Guatemalan volunteers in their ranks. On March 15, Morazán and his army were on their way to occupy their previous positions, he was intercepted by the federal troops of Colonel Prado at the Las Charcas ranch. Morazán, with a superior position, crushed Prado's army. The battlefield was left littered with corpses, prisoners and weapons. Subsequently, Morazán with the Écija militia moved to recover his old positions in Pínula and Aceytuno, and again lay siege to Guatemala City.

General Verveer, Minister Plenipotentiary of the King of the Netherlands before the Central American Federation, tried to mediate between the State Government and Morazán, but they could not reach an agreement. Military operations continued with great success for the allied army. On April 12, the Guatemalan head of state, Mariano de Aycinena y Piñol, leader of the powerful Aycinena Clan, capitulated and the following day the Central Plaza was occupied by Morazán's troops. Immediately after, President Arce, Mariano Aycinena, Mariano Beltranena, and all the officials who had played a role in the war were sent to prison. After these events, General Morazán expelled the most important ecclesiastics and all members of the Aycinena Clan -that is, members of the conservative party- and led the country dictatorially, until Senator Juan Barrundia took office on 25 June 1829.

Second term in Honduras

On March 5, 1829, Morazán and Diego Vigil were appointed head and deputy head of state by the Honduran Legislative Assembly. That same month, on the recommendation of the government, Morazán bought and transferred from Guatemala the first printing press in Honduras, installed in the San Francisco Barracks under the direction of the Nicaraguan Cayetano Castro. This was released with a proclamation to the department of Olancho by Morazán, to prevent them from turning against him, dated December 4, 1829, the same in which he assumed the position of head of state after his return. to Honduras. On December 24, he left the government in the hands of Juan Ángel Arias to undertake the pacification of Olancho, which ended with the signing of an agreement on January 21, 1830, where the people of Olancho promised to obey the Government of Honduras.

On February 19, he defeated an insurrection in Opoteca and resumed leadership of state on April 22. During this term he founded the first official newspaper of Honduras, La Gaceta del Gobierno .In June he won the elections for President of the Federal Republic of Central America; same month that he sent Dionisio de Herrera to pacify Nicaragua. Morazán resigned as the head of Honduras on July 28, which was assumed the following day by the deputy head of state, Diego Vigil.

Presidency of the Federation

Period 1830-1834

Francisco Morazán won the popular vote in the 1830 presidential election, in which he was opposed by the moderate José Cecilio del Valle. The new president took office on September 16 of the same year. In his inaugural address, he stated:

"The sovereign people send me to the most dangerous of their destiny. I must obey and fulfill the solemn oath I have just given. I offer to uphold the Federal Constitution that I have defended as a soldier and a citizen. »Francisco Morazán

With Francisco Morazán as president and his support for the governors, the liberals had consolidated power. In this way, the new president and his allies found themselves in an excellent position to implement his reforms, which were inspired by the philosophy of the Enlightenment. Through these, the president would try to dismantle in Central America what he considered to be archaic institutions inherited from the colonial era since they had only contributed to the region's backwardness. According to traveler John Lloyd Stephens, General Morazán wanted his people to have a society based on universal education, religious freedom, and social and political equality.

In 1831, Morazán and Governor Mariano Gálvez turned Guatemala into a political laboratory. The construction of schools and roads was supervised, free trade policies were enacted; foreign capital and immigrants were invited; marriage, secular divorce, and free speech were allowed; public lands were made available for cochineal expansion; the Church of the State was separated; tithes were abolished; freedom of religion was proclaimed; ecclesiastical property was confiscated, religious orders were suppressed, and the control it had over education was withdrawn from the Catholic Church, among other policies.

With the implementation of these revolutionary measures, Morazán became -according to the writer Adalberto Santana- the first president of Latin America who applied a liberal thought to his administration. This dealt a hard blow to the Creoles of the City of Guatemala, but the most important thing was the stripping of the regular clergy of their privileges and the reduction of their power.

According to writer Maria Wilhelmine Williams: "The immediate reasons for the different enactments varied. Some laws were designed to protect the status of the clergy... Others were aimed at helping to recover the public treasury, and, at the same time, sweeping away aristocratic privilege; while other legislation ―especially the latest ones― was enacted to punish opposition to previous events and intrigues against the government", when Francisco Morazán came to power.

At that time, Morazán ordered the arrest and expulsion of Archbishop Ramón Casaus y Torres, effective on the night of July 10, 1829, as well as 289 friars, members of the Dominican, Franciscan and Recoleta orders, since they were on suspicion of opposing independence. Casaus y Torres traveled from Guatemala to Omoa guarded by General Nicolás Raoul and on the back of a mule, where members of the Betlemita and Mercedaria orders were waiting for him in two sailboats for their transfer to Havana, who were not captured or reprimanded for not participating in policy. For his part, Casaus y Torres rendered accounts to the King of Spain about his political conduct in Central America, as if the Archbishop of Guatemala had been a position of the Spanish Crown and not of the Holy See. Consequently, King Ferdinand VII granted him a pension of 3,000 pesos, and soon after he was named Archbishop of Havana until 1845.

During the civil war, religious leaders had used their influence against General Morazán and the liberal party. They had also been opposed to the reforms, particularly those to do with universal education, which the Liberals were determined to implement at any cost.

In March 1832, another conflict broke out in El Salvador. The head of state José María Cornejo had rebelled against some federal decrees, forcing President Morazán to act immediately. As commander-in-chief, he led the federal troops that marched to El Salvador where they defeated the army of Chief Cornejo on March 14, 1832. On the 28th of the same month, Morazán had occupied San Salvador. From then on, rumors began about the need to reform the Constitution.

Period 1835-1839

In 1834, at the request of Governor Mariano Gálvez, General Morazán moved the capital of the Federal Republic to Sonsonate and later to San Salvador. The same year, the first four years of Francisco Morazán's presidency had ended. According to the constitution of 1824, new elections had to be held in order to choose the next president.

Moderate conservative José Cecilio del Valle ran as the opposition candidate for incumbent President Francisco Morazán. For this reason, the general handed over the presidency to Gregorio Salazar, so that the Federal Congress could verify the impartiality of the election.

When all the votes were counted, José Cecilio del Valle defeated Francisco Morazán. The results of the federal elections demonstrated strong popular opposition to the liberal reforms. Valle, however, died before taking office. Most historians agree that if Valle had not died, he could have created a conciliation government between the opposition forces (liberals and conservatives). Due to these facts, on June 2, the Federal Congress called a new election which was won by Francisco Morazán. On February 14, 1835, he was sworn in as president for a second term in Guatemala City.

End of the Federation

In February 1837, a series of dramatic events occurred in Central America, igniting a revolution that culminated in the end of the Federation. A cholera epidemic hit the state of Guatemala, leaving approximately 1,000 dead and 3,000 infected with the bacteria. The epidemic hit the poor and indigenous people especially hard in the highlands of the state and spread rapidly. The government of Mariano Gálvez, hoping to alleviate the situation, sent available doctors, nurses, and medical students and the medicines for distribution; but these measures were of little help, for the Indians continued to die.

At the time cholera broke out, the indigenous people of the Mita district, influenced by their priests, were furious at the (incomprehensible to them) trial by jury system that Chief Gálvez had introduced. The church he saw all this as an opportunity to strike a blow against the liberal government of Gálvez, as the local priests spread the rumor that the government had poisoned the rivers and streams with the purpose of annihilating the indigenous population. As proof of this, they showed to the Indians a recent grant of territory in Verapaz that had been made to a British colonization company.

The riotous Indians repudiated their alleged murderers. With cholera spreading, they took up arms, killed white people and liberals, burned their houses, and prepared to face the Gálvez government who sent an army to try to stop the revolt. But the army's measures were so repressive that they made things worse. In June, Santa Rosa de Mita rose up in arms and a new caudillo named Rafael Carrera y Turcios emerged from the town of Mataquescuintla. The young Carrera was illiterate, but astute and charismatic. He had also been a hog farmer who had become a highwayman, but whom the rebels wanted as their leader.

The priests announced to the natives that Carrera was their protective angel, who had descended from heaven to take vengeance on heretics, liberals, and foreigners and to restore their ancient rule. They devised various tricks to make the Indians believe this illusion, which were announced as miracles. Among them, a letter was thrown from the roof of one of the churches, in the middle of a vast congregation of indigenous people. This letter supposedly came from the Virgin Mary, who commissioned Carrera to lead a revolt against the government.

Under cries of "Long live religion!" and "Death to foreigners!" Carrera and his forces launched a war against the government. Encouraged by these events, the conservatives joined the revolt. Meanwhile, the government of Mariano Gálvez requested military aid from General Morazán.

By the time Morazán arrived in Guatemala City, Gálvez had already left the head of state. The group in power granted him full powers to face Rafael Carrera, they also offered him the lifetime presidency, but Morazán rejected this offer, because it was against his liberal principles. Morazán then called on Carrera to lay down his arms, but the rebel leader opposed it. Carrera was defeated and persecuted by Morazán on several occasions, thus managing to pacify the state. But the general was never able to apprehend the indigenous leader, as he simply withdrew into the mountains and returned to occupy key positions as soon as Morazán's troops left the state of Guatemala.

By 1838 Morazán presided over a dying federation. Congress tried to revive the Federal Government by giving it control of its customs revenue. But Honduras, Nicaragua and Costa Rica opposed it and used this excuse to leave the Union. The Federation was dead. On February 1, 1839, Morazán had finished his second term as constitutional president, Congress had dissolved, and there was no legal basis for naming his successor. In the end, ignorance, the power of the Church, the bitter internal struggles between conservatives and liberals, and the search for personal glory, were the main reasons for the dissolution of the Federation.

Head of State of El Salvador

After his second term as president of the Federal Republic ended, Morazán was left without political or military power. On July 13, 1839, however, the general was elected head of state of El Salvador. When Rafael Carrera and the Guatemalan conservatives realized the new role he was playing, they decided to declare war on El Salvador. The general had become the very personification of the Federation, he was the body and soul of the Constitution of 1824, and eliminating him meant ending any ideas or hopes that had remained for the Federation.

For that reason, his enemies did not want him to be in command of that nation, or of any other Central American state, and they promised to defeat him. On July 24, 1839, Nicaragua and Guatemala entered into an alliance treaty against the Morazán government in El Salvador. Later, on August 24 of the same year, the Guatemalan leader Rafael Carrera y Turcios would call Salvadorans to a popular insurrection against his president. These calls provoked some uprisings, which were put down without much effort by the government.

Unsuccessful internally, the general's enemies formed an army made up of Honduran and Nicaraguan troops. On September 18, 1839, Morazán was in El Salvador to prevent the advance of the hosts of Francisco Ferrera, but a mutiny occurred in San Salvador and the plaza was controlled by Pedro León Velásquez; The rebels sent a message to the general in which they threatened to kill his wife, his son Francisco and the newborn Adela if he did not capitulate, but Morazán responded with these memorable words:

The hostages that my enemies have are sacred to me and speak very high to my heart, but I am the Head of State and I must attack passing over the bodies of my children; but I will not survive so terrible misfortune.

However, Morazán managed to retake San Salvador, while León Velásquez surrendered himself unconditionally and desisted from the threats against the general's family, who also spared his life.

On September 25, Morazán triumphed in the Battle of San Pedro Perulapán, in which he only needed 600 Salvadorans to defeat the more than 2,000 men commanded by Generals Francisco Ferrera, Nicolás de Espinosa and Manuel Quijano y García. After the defeat, the humiliated generals and their troops fled to neighboring states, leaving behind more than three hundred dead.

On March 18, 1840, Morazán made one last attempt to restore the Union. He gathered some 1,300 men and marched with them to Guatemala. Once positioned, Morazán marched from the south, attacking Carrera's men located in the capital. But Carrera had set him up, for he had drawn most of his own force out of the capital, leaving only a small, highly visible garrison inside. In this way Morazán and his men finished off the bait, but then they found themselves assaulted from all directions by Carrera's forces of about 5,000 men. It was a battle notorious for its savagery and revealed the ruthless side of Carrera, whose men chanted "Salve Regina" and shouted "Long live Carrera!" and "Death to Morazán!"

The next morning, Morazán was running low on ammunition. He then ordered increased fire from three corners of the plaza, in order to attract attention, while he and some of his officers barely escaped with their lives to El Salvador. Carrera's victory was decisive.On April 4, 1840, before a meeting of notables, Morazán declared his resignation and his resolution to leave the country, since he did not want to cause more problems for the Salvadoran people.

Exile to Peru

On April 8, 1840, General Francisco Morazán went into exile. He left from the port of La Libertad (El Salvador), aboard the schooner Izalco accompanied by 30 of his closest friends and war veterans. Upon arriving in Puerto Caldera (Costa Rica) he requested asylum for 23 of his officers, which was granted. Seven of them continued their trip to South America in his company. Morazán arrived in Chiriquí, and then went to David, Panama, where his family was waiting for him. While in this town, Morazán was informed by his friends about the terrible persecutions suffered by his supporters at the hands of Rafael Carrera and other Central American liberal leaders.

Outraged by these events and by the chain of insults and slander against him by some members of the press, Morazán wrote and published his famous David's Manifesto dated July 16, 1841. In this manifesto, Morazán attacks the serviles whom he accuses of being "petty men" and abusers of the most sacred rights of the people. He also reminds them that they opposed the independence of Central America, and sacrificed freedom by joining Iturbide's empire. Therefore, he lets them know that Central America is not their homeland, but the homeland of those who "made the cry of independence resound throughout the Kingdom of Guatemala... and they felt electrified with the sacred fire of freedom."

Morazán was still in David when he received calls from his liberal colleagues in Costa Rica. Braulio Carrillo, governor of that state, had restricted individual liberties, limited freedom of the press, and had repealed the Political Constitution of 1825, which was replaced by a new constitutional charter, called the "Bases and Guarantees Law," which declared, in its articles 1 and 2, that the head of state of Costa Rica was "elected by the people" (article 1) and that he was "immovable" (article 2), which his enemies turned into "for life", calling him then "dictator" over and over again. On the other hand, Carrillo had also declared Costa Rica a free and independent state. Despite these facts, Morazán wanted to stay away from the political affairs of Central America, and continued his trip to Peru. Once in Lima, he received an invitation from Marshal Agustín Gamarra to command a Peruvian division, at a time when his country was at war with Chile. However Morazán refused, because he found that this war was very confusing. For more than twelve years, the dissensions between the Republics of Peru and Bolivia -in which the States of Chile and Colombia were involved- gave rise to a series of wars with reciprocal successes and failures, which caused disastrous stages of chaos between all parties that were belligerent.

In Peru, Morazán was fortunate to find good friends with whom he shared the same ideals. Among these were Generals José Rufino Echenique and Pedro Pablo Bermúdez. Around 1841, the British began to intervene in the Mosquitia territory, located between Honduras and Nicaragua. This event prompted Morazán to put an end to his self-imposed exile in Peru, and he decided that it was time to return to Central America because he considered it a "duty" and an "irresistible national sentiment" not only for him, but for everyone." those who have a heart for their homeland." With the financial backing of General Pedro Bermúdez, he left El Callao at the end of December 1841 aboard the ship El Cruzador. On that trip he was accompanied by General José Trinidad Cabañas, José Miguel Saravia, and five other officers. He and his companions made stops in Guayaquil, Ecuador and Chiriquí, Panama, where he had the opportunity to meet his family once more before returning to Central America.

Supreme Chief of Costa Rica

Defeated by General Carrera, Morazán left El Salvador and took refuge in the Panamanian town of David (Chiriquí), which at that time was part of Colombia. Based there, Morazán conceived, at the suggestion of Carrillo's enemies, the idea of invading Costa Rica. The opposition to Carrillo was really a minority, but his strength lay in the request for foreign aid that they made. Costa Rica, although he was not particularly interested in it, served him for his expansionist purposes in the rest of Central America, in addition to being able to provide him with men, weapons, and money, since returning to Central America and facing Carrera again was one of his goals. objectives.

On April 7 and without any setbacks, Morazán's fleet, which was made up of five ships, disembarked in the port of Caldera, Costa Rica, but its march did not begin until the 9th of the same month. "Carrillo issued a decree in which he ordered the entire army to gather for the defense of the State against the foreign enemy", his defense plan contemplated a group of men in charge of the Salvadoran Vicente Villaseñor, who with his betrayal, would truncate said project of defending. «Carrillo did not want bloodshed, so he thought of talking to Morazán (...) Carrillo failed to invite him to Morazán. The invading general had already arranged an interview and not precisely with the Costa Rican president, but with Villaseñor, who would hand over the forces that had been placed at his command», thus he and Vicente Villaseñor signed the Pact of El Jocote. The agreement provided for the integration of a single military body, the convocation of a National Constituent Assembly, the expulsion of Braulio Carrillo and other members of his administration, and the installation of a provisional government under the command of Francisco Morazán. «Carrillo read the treacherous pact carefully. He knew that he could face Morazán's forces, but also that a wave of blood would be unleashed. If Morazán and Villaseñor didn't care about that, it worried him deeply. He thought that if he was the person under discussion, he would step aside, leave the country, sacrifice his work (...) Carrillo agreed to approve the pact, subject to some modifications ». On April 13, 1842, Morazán's forces entered the city of San José, "an hour later Carrillo began his exile" to El Salvador.

Morazán's first act was to open the doors of the State to Costa Rican and Central American political refugees. In addition, the new ruler dedicated himself to repealing some of the laws issued in Carrillo's time and devoted himself to other reforms. He likewise convened a Constituent Assembly which appointed him supreme head of the State of Costa Rica.

Upon his arrival at Puerto Caldera, «Morazán brought with him a document known as the Caldera Proclamation; in this he offered to the Costa Ricans to restore freedom to Costa Rica and proclaimed war against Carrillo, whom he called a tyrant, despot, ignorant and bloodthirsty", qualifications that "Morazán forgot that he was no less deserving of these epithets, as he did not The people to whom he promised to restore freedom were slow to experience it painfully." By September 1842, Morazán had already lost most of the initial support that had brought him to power in Costa Rica. His presence in Costa Rica had aroused great fear in the rest of the Central American states: Guatemala declared Costa Rica an enemy country; El Salvador broke relations, and Honduras and Nicaragua ignored the Morazán government. The four states were organized in the so-called "Confederation of Guatemala", a military union against Costa Rica in which they agreed to "help each other and make common cause in case the independence of all and any of them was attacked". To this was also added that on July 29, 1842, Morazán, in a long manifesto, communicated to the Costa Ricans his intention to remake the Central American Union by force of arms.

Death

On September 11, 1842, a popular movement against the Morazán government broke out in Alajuela. Four hundred men headed by the Portuguese Antonio Pinto Soares. Given these facts, Morazán and his men managed to repel the attacks and retreated to the headquarters. From there they faced the insurgents who, according to the historian Montúfar, numbered a thousand men.

The fighting continued fierce and tenacious. As the conflict was unfavorable to the besieged, Chaplain José Castro proposed a capitulation to Morazán guaranteeing his life, but he refused. After 88 hours of fighting, Morazán and his closest collaborators decided to break the siege. General José Trinidad Cabañas with 30 men made possible the withdrawal of Morazán and the officers close to him towards Cartago.

Nevertheless, the insurrection had spread to that place and Morazán had to request help from his supposed friend Pedro Mayorga, however, he betrayed him and gave Morazán's enemies facilities to capture him along with generals Vicente Villaseñor, Saravia and other officers. General Villaseñor tried to commit suicide with a dagger and was seriously injured. He fell to the ground covered in blood but survived. General Saravia died after suffering a terrible convulsion.

Subsequently, a "mock trial" was carried out, in which Morazán and Villaseñor were sentenced to death by the self-constituted new authorities. According to historian William Wells: "The junta that issued this barbaric resolution was composed of Antonio Pinto (made commander general at that time), Father Blanco, the infamous doctor Castillo, and two Spaniards named Benavidez and Farrufo."

After these events, the condemned were transferred to the firing squad located in the central square of the city. Before the act of execution was carried out, Morazán dictated his will to his son Francisco his. In this, the general stipulated that his death was a "murder" and also declared: "I have no enemies, nor do I carry the slightest grudge against my murderers, I forgive them and wish them the greatest possible good." Later they offered him a chair and rejected it. To General Villaseñor, who was sitting unconscious and under the effect of a sedative,[citation needed] Morazán said: "Dear friend, posterity will do us justice" and he crossed himself.

According to the historian Miguel Ortega, Morazán asked to command the escort, opened his black coat, uncovered his chest with both hands and with an unchanging voice ―like someone giving orders in a military parade―, he ordered: « Prepare weapons! Aim!" He then corrected the aim of one of the shooters and finally yelled: «Aim! Was...!". The last syllable was muffled by a closed discharge. Villaseñor received the impact of the bullets in the back and fell flat on his face. Among the smoke from the gunpowder, it was seen that Morazán raised his head slightly and muttered: "I'm still alive...". A second discharge ended the life of the man whom José Martí described as follows:

- "a powerful genius, a strategist, a speaker, a true statesman, perhaps the only one who has produced Central America."

In October 1842, the Central American governments, satisfied that Morazán had disappeared, resumed relations with Costa Rica.

In 1848, the government of José María Castro sent Morazán's remains to El Salvador, fulfilling one of his last wishes.

Legacy

Alta is the night and Morazán watches. Invaders filled your abode. And they broke you like dead fruit, and others sealed on your back the teeth of a blood styre, and others plundered you in the ports carrying blood on your pains. —(Pablo Neruda: General chant, XXXI).

|

Francisco Morazán became a martyr and a symbol of the Republic of Central America. He gave his life, albeit unsuccessfully, trying to preserve the union of these countries. It is also evident that his death contributed, to a certain extent, so that each of these nations are independent countries today.

His image can be found on banknotes, logos, postage stamps, institutions, cities, departments, schools and parks, among other things that preserve his legacy. El Salvador was one of the first countries to pay tribute to Morazán. On March 15, 1882, President Rafael Zaldívar unveiled a monument in his memory, located in Plaza Francisco Morazán, and, on March 14, 1887, the National Assembly of the Republic of El Salvador replaced the name of the Department of Gotera by Department of Morazán, "to perpetuate the name of the great leader of the Central American Union". President Doroteo Vasconcelos also named the village "San" Francisco Morazán in his honor. In Honduras, the name of the department from Tegucigalpa was changed to Francisco Morazán in the year 1943. In Guatemala, the Guatemalan city of Tocoy Tzimá became Morazán on November 15, 1887. In Nicaragua, Puerto Morazán was founded in 1945.

In the political arena, the idea of integration remains in the minds of many Central Americans. For example, the Central American Parliament (Parlacen) is a political institution dedicated to the integration of the countries of Central America, which represents a modern version of the historic Federal Republic of Central America, although without Costa Rica, but which includes Panama and the Dominican Republic. In the past several unsuccessful attempts have been made to re-establish the Union (1851, 1886 and 1921).

Morazán's legacy is also present in the arts. The first recorded work in El Salvador is entitled The tragedy of Morazán, written by Francisco Díaz (1812-1845), which is a dramatization of the life of the president of Central America. Likewise, in Honduras the play by Luis Andrés Zúñiga Portillo called Los conspiradores (1916) was staged, which was a historical drama that honored the virtues of Francisco Morazán. In his book Canto general, Pablo Neruda also pays homage to the "liberal caudillo" with a poem to Central America. Statues and busts of Francisco Morazán can be found in Chile, Panama, El Salvador, the United States, Spain, Honduras, Costa Rica, and Nicaragua, among others.

Acknowledgments

Portraits of Francisco Morazán

General Morazán was white, slightly sounded; of thin, tall and straight body; the set of factions constituted such a perfectly delineated physiognomy that, seeing it once, it could not be forgotten, always remembering much of the Greek type... Severely pundonorous and proving character, he never abused power for his own benefit; the outside of his family; his house, his rivet, his dress; all carried the seal of modest decency.José María Cáceres.

He was about 45 years old; five feet and ten inches tall; he was thin, with black beard and moustache and wore a sword and a military shell bent to the throat. He was without a hat and the expression of his face was soft and intelligent [...] he always led his troops; he had been in numerous battles and had often been hurt, but never defeated.John Lloyd Stephens

No frivolity was noticed in their customs, so pure, simple and arranged. He ran away from the amusements, just like to show up and look. He avoided the demonstrations of sympathy, banquets and liviandades, but he was very pleased with the treatment of enlightened men, even if they were their enemies. [...] No one feared him, for he was never seen an act of ferocity or disobedience. His greatest enemies, they put their rage in his presence, because seeing him it was impossible to hate him.Antonio Grimaldi.

Hymn to Francisco Morazán

Magical bronze rhyme that sings the wonder of your epic story on the summits my muse raises the fabulous splendor of your glory.

Let your figure light up your flame that radiate the beans of mother-of-pearl and gold solemn hymn pregone your fame lives in the air your sound name.

Echo of love in the high confines is wandering in the green pine trees weep your death the clear clarines and in your deep responsibility the seas.

In addition to arcane accents of your name, oblivion floats the ideal of the union of the winds as a pavilion to the future lying.

Whoever your figure cranks us with flowers spends your numen beating vestiges like sunshine with no fulgors on the eternal radar of the centuries.

Patria salutes the heroic hymn warrior rising from light and victory loves the sublime fulgor of his steel put on his forehead the bay of glory.

Busts, statues and monuments in the world

There are several monuments in honor of the memory of this caudillo. One of the most representative and oldest is Plaza Francisco Morazán, in the historic center of the City of San Salvador (El Salvador), where there is a bronze statue of General Francisco Morazán on a marble pedestal in where five women are found each holding the shields that in 1882, the year the plaza was inaugurated, were held by each of the five Central American republics that made up the Federal Republic of Central America. In fact, this monument is the oldest in the Salvadoran capital that is still standing. There is also a monument with his bust in Panama, Panama City, in Urraca Park located on the Cinta Costera in front of the Miramar Hotel.