Francisco de Zurbaran

Francisco de Zurbarán (Fuente de Cantos, Badajoz, November 7, 1598 – Madrid, August 27, 1664) was a painter of the Spanish Golden Age.

A contemporary and friend of Velázquez, Zurbarán excelled in religious painting, in which his art reveals great visual power and deep mysticism. He was a representative artist of the counter-reformation. Influenced early on by Caravaggio, his style evolved to approximate the Italian Mannerist masters. The representations of him move away from the realism of Velázquez and his compositions are characterized by chiaroscuro modeling with more acid tones.

Biography

Training and first jobs

Francisco de Zurbarán was born on November 7, 1598 in Fuente de Cantos (Badajoz). His parents were Luis de Zurbarán, a merchant of Basque origin established in Fuente de Cantos since 1582, and Isabel Márquez, who had married in the town of Monesterio on January 10, 1588. It is not known why the painter sometimes signed as Francisco de Zurbarán Salazar. Two other important painters of the Golden Age would be born shortly after: Velázquez (1599-1660) and Alonso Cano (1601-1667).

On January 15, 1614, he entered the workshop of the painter Pedro Díaz de Villanueva, in Seville, where he was able to meet Alonso Cano in 1616. His apprenticeship ended in 1617, the year in which he married María Páez, in Llerena, where he settled. Three children were born from this marriage, all baptized in Llerena: María (baptism: February 22, 1618), Isabel Paula (baptism: July 13, 1623). and Juan de Zurbarán (baptized July 19, 1920) who was a gifted painter, who died very young.

His first known canvas is the Virgin of the Clouds (ca.1619-1620) perhaps made for an altarpiece in a church in his hometown. After his first wife died in 1623-1624, he contracted a second marriage in 1625 with Beatriz de Morales —from Llerena and also a widow— with whom he had no children, and who would die on May 28, 1639, in Seville.

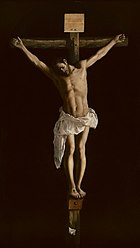

On January 17, 1626, as a resident of Llerena, he signed his first contract for a religious order —the Convent of San Pablo el Real (Seville)— for twenty-one paintings, for a total of 4,000 reales. As a complement to this ensemble, he painted the impressive Crucified—signed and dated 1627—origin of his fame in Seville. Zurbarán represented an almost naked body, with perfect anatomy, little bloody, calm after the sacrifice, dramatized by the violent lighting coming from the right. His serenely beautiful head, tilted to his right, and the perizome—bulging in folds of dazzling white—avoid the monotonous symmetry of Pacheco's Crucified .

The moving canvas San Serapio —signed and dated 1628— was commissioned by religious Mercedarians who, in addition to the three traditional vows, pronounced a vow of "redemption or blood," giving up their lives in exchange for the ransom of the captives. Zurbarán avoided the bloody details of the torture to which Saint Serapio was subjected due to this vow, preferring to hide the saint's body under a beautiful Mercedarian habit and scapular.

Perhaps this San Serapio was the origin of the notable contract that Zurbarán obtained on August 29, 1628. Even as a resident of Llerena, he undertook to make —in one year— twenty-two paintings about life of San Pedro Nolasco, for the Convent of La Merced (Seville), charging for it 1500 ducats plus the materials. With his officers, he moved from Llerena to Seville to carry out said work.

The set of paintings for the Colegio de San Buenaventura (Seville) dates from 1628-1629. Between June 21 and 27, 1629, the Seville municipal council expressed its desire for Zurbarán to settle in this city.

Culmination period, first trip to Madrid and return to Seville

On September 19, 1629, Zurbarán lived with his family in Seville, at nº.27 Callejón del Alcázar. Recently installed, he receives a commission for the Convent of the Trinity. Calling himself "master painter of the city of Seville", Zurbarán aroused the jealousy of painters such as Alonso Cano. On May 25, 1630, he refused to pass the exam that union members who worked in Seville had to take, alleging that this city had declared him a "distinguished man."

On June 8, 1630, the Municipal Council of Seville commissioned an Immaculate Conception for a hall of the Town Hall. The Vision of San Alonso Rodríguez dates from 1630, and on January 21, 1631 he contracted, for the Colegio de Santo Tomás, the Apotheosis of Santo Tomás de Aquino, the largest canvas of the pictorial corpus of he. On December 29, 1632, he rented a house on Calle Ancha, from the Church of San Vicente (Seville).

From this stage —considered the richest and most personal— there are some two hundred paintings, many of them signed, which indicates that Zurbarán was proud of them. The painter gradually improves the grouping of the figures in the composition, where the landscape and the architectural elements have more or less interest, depending on their relative function. In the works that require it, the background is practically golden, to signify a celestial scene.

On June 12, 1634 —in Madrid— he charged 200 ducats on account of 144,309 reales and 26 maravedis, for the twelve paintings he was to paint from the Series of the Labors of Hercules in the Salón de Reinos, in the Buen Retiro Palace. On August 9 and October 6, he collects separate items for the same concept. On November 13, he declared that he had received the amount stipulated for ten paintings of The Labors of Heracles, and for two of the Defense of Cádiz against the English. The paintings representing Hercules are not the best of the painter's corpus, since the hero had to be represented half-naked, and Zurbarán did not master anatomy.

This trip to Madrid was decisive for his pictorial evolution, due to his meeting with Diego Velázquez, and the vision of the works of the Italian and Flemish painters who worked at the court. From then on, the tenebrism and caravagism of his beginnings softened, his cloudscapes became lighter and the tones less contrasted.

On August 19, 1636, endowed with the title of "King's Painter", he returned to Llerena, to carry out works in the church of Nuestra Señora de la Granada, worth 3,150 ducats, helped by Jerónimo Velázquez, whom He granted a power of attorney —May 4, 1641— to collect what was owed for these works. In 1637 he charged for some paintings in the sacristy of the Church of San Juan Bautista (Marchena). On March 4, he appraised the painting of two pulpits in Seville, and on May 26, he contracted the painting of six paintings for the Convento de la Encarnación in Arcos de la Frontera, which he received on August 27, 1638. With Alonso Cano and Francisco de Arce, he appears as guarantor of José de Arce for an altarpiece in the Cartuja de Jerez.

In 1638, his daughter María married the Valencian José Gassó on March 5, and on July 17 Zurbarán received 914 reales for the decoration of the ship "El Santo Rey San Fernando", a gift from the city of Seville Felipe IV for the Retiro Park. In 1638-1639 he commissioned the works for the Cartuja de Jerez de la Frontera. On March 3, 1639, he commissioned the series of paintings for the Monastery of Guadalupe, charging amounts in 1640, 1643, 1646 and 1647 for these canvases and other works. On August 18, 1641, his son Juan —21 years old— married Mariana de Quadros in Seville.

Period 1641-1658

The fall of the Count-Duke of Olivares —1643— and various political adversities aggravated the decline of the Hispanic monarchy, with negative effects in Seville, which contributed to worsen those of the great plague of 1649. The consequent economic debacle of the city, it is worth adding a change of taste regarding Art, to which Zurbarán could not adapt, being surpassed by new artists, especially Murillo and Herrera el Mozo.

Some two hundred canvases survive from this period, generally of medium size, of acceptable quality. They show little will to renew, and few are signed and dated. If it is admitted that Zurbarán signed —sometimes dated— those of which he was proud, surely a large part of the two hundred canvases are basically the work of the workshop. Topics covered include: the Crucified One, Founding Saints, and the Virgin and Child. Many of their Immaculate and Vírgenes mártires are from this period, and curious subjects also appear, such as Jacob and his twelve sons or The Infants of Lara. Only at the end of this stage did he hire a monastic complex equivalent to those of the previous phases: that of the Cartuja Monastery.

After Isabel Márquez died, Zurbarán married his third nuptials in Seville —February 7, 1644— with Leonor de Tordera, with whom he had six children, baptized in Seville: Micaela-Francisca on May 24, 1645, José Antonio on May 2, April 1646, Juana Micaela on February 9, 1648, María on April 9, 1650, Eusebio on November 8, 1653 and Agustina Florencia on November 2, 1655.

In 1644 he finished the altarpiece for the chapel of Los Remedios, in Zafra, and commissioned two paintings for the Rosario brotherhood, in Carmona. On May 25, 1644 he leased a house on Borceguinería street, and in 1645 he lived in a house in Los Alcázares Viejos, which on May 31, 1652 he transferred for 22,000 reales. On June 8, 1649, his son Juan —a notable painter— died due to a great plague in Seville.

On 4 January 1652, enter the Costume of the Holy Charity. In 1655, the prior of the Monastery of the Carthusian commissioned the three large canvases for the sacristy of the monastery. In 1656, Zurbarán and his family appeared on the street of the Abades n or.1, house 267. In November-December 1656, the painter and his wife were sued for debts and in 1658 they resided on Calle Abades, house 262, Seville.

Second trip to Madrid

In May 1658, Zurbarán traveled again to Madrid, continuing his family in Seville. On December 23, he testified in favor of Diego Velázquez, in the investigation on him for his admission into the Order of Santiago. His friend Diego Velázquez died on August 6, 1660.

In a document dated June 10, 1659, it is stated that Zurbarán and his wife resided in Madrid, Calle de las Carretas, parish of Santa Cruz. The works carried out at this time are relatively few, but those that are signed abound. Zurbarán renewed both his repertoire and his technique, since the monastic clients were replaced by individuals who requested other themes, represented with a different sensibility. The painter uses subtle shading, firm but delicate modeling, and refined lighting that highlights the beautiful polychromy of objects and figures. His last known work —dated 1662— is Virgin with Child and Saint John (Bilbao Museum of Fine Arts).

On August 27, 1664, Francisco de Zurbarán died in Madrid. The discovery in the Old General Archive of Protocols of Madrid of the inventory of his assets —drafted in 1665— shows that he lived in an acceptable level of well-being. He was buried in the Copacabana convent, destroyed in the XIX as a result of the confiscation of Mendizábal, losing the remains of the painter.

Museum House

His birthplace in Fuente de Cantos has been rehabilitated and has the most modern technologies to take visitors back to the time of the great painter from Extremadura. A museum that belongs to the network of Identity Museums of Extremadura.

Historical, religious and artistic context

In 1600 there were thirty-seven convents in Seville. Over the next twenty-five years another fifteen were founded. The convents were the great patrons of the painters, very demanding in terms of the composition and quality of the works: so much so that Zurbarán, by means of a contract, promised to accept the return of all those paintings that were not to the liking of the religious.

The religious men and women were very sensitive to the aesthetic dimension of the representations, and they were convinced that beauty was more stimulating for the elevation of the soul than mediocrity. These abbots and abbesses were, normally, cultivated, erudite, refined people, with a very sure criterion in front of works of art.

In churches there was always an altarpiece depicting scenes from the life of Christ. In addition, during the 17th century, the sacristies -places where priestly vestments are changed- were increasingly decorated richly. Likewise, paintings were placed in the cloister, in the refectory, in the cells (many of these medieval works were destroyed). In the libraries and chapter rooms, you could find pictures of the founder of the Order and its most important personalities.

These demands were typical of all convents. The second-order paintings could be made in series, but the recognized masters renewed themselves, deepened their art and received many more commissions.

Zurbarán and America

Seville, was «Puerto y Puerta de las Indias», the great Spanish port for trade with the Kingdoms of the Indies. The galleons arrived in Seville loaded with gold and set sail with Spanish products, including works of art, generally considered mere merchandise. Perhaps Zurbarán came into contact with the American market —ca.1635— with the canvas Pentecostés (Museo de Cádiz) from the Consulate of Shippers to the Indies, but the first known documents in this regard date from 1638, showing that he had already been negotiating with America for some time. On January 16 of this year, he deferred part of the payment of his daughter María's dowry until the arrival of the galleons, and on April 10 he granted a power of attorney to collect what is owed in Lima.

From the year 1647 there are three documents referring to Lima: on May 22 he collected 2000 pesos from the abbess of the convento de la Encarnación, to paint "ten scenes from the life of the Virgin, plus twenty-four standing virgins". On May 25, he received 1,000 pesos for paintings that were to be sold there. On September 23 and November 3, he granted a power of attorney to collect twelve paintings with "Roman Caesars on horseback." On February 27, 1649, a receipt is signed in Buenos Aires for a batch of fifteen virgin martyrs, fifteen kings and illustrious men, twenty-four saints and patriarchs, and nine "countries of Flanders", from Zurbarán's workshop, to be sold in the city. As of this date, only two documents are known linking him to America: the powers signed —already in Madrid— in 1660 and 1662, to collect that shipment to Buenos Aires.

Of the seven documents preserved, naming the city, Lima was four and none of the cities of the Viceroyalty of New Spain, but it must be considered that one was the place where the canvases were sent, and another where the in the end they were sold. Interesting facts are that only one contract —that of the nuns of La Encarnación, in Lima— was not instance of a party, like those signed for the communities of Spain, and that Zurbarán's trade with America was increased in the years 1640-1650, when its Andalusian clientele dwindled.

An exceptional example of his production for America is the series about Jacob and his twelve sons currently in Auckland Castle, which is supposed to have missed its destination due to a pirate attack.

The pictorial work of Zurbarán

Charges from religious orders

Order of Mercy

The Mercedarian order, founded by Saint Pedro Nolasco in 1218, was later influenced by the Discalced Carmelites, forming —in 1603— the order of the Descalced Mercedarios, for whom Zurbarán worked in two convents in Seville:

La Merced Convent (Seville)

Deep Room

The moving San Serapio —signed and dated 1628— (Wadsworth Atheneum) was perhaps the proof of ability that the friars of this convent needed to entrust to Zurbarán the considerable collection on the life of Pedro Nolasco in the cloister of the boxwoods.

Cloister of the boxwoods

Nolasco was canonized in 1628, the year in which Zurbarán received the commission for twenty-two canvases for the boxwood cloister, which allowed him to move his residence from Llerena to Seville. Of this set —which perhaps was not completed— ten works have been preserved. It seems that Zurbarán only took part in a few canvases, making use of collaborators and basing himself on prints by Jusepe Martínez. Six paintings by Zurbarán are preserved: Departure of Saint Peter Nolasco for Barcelona (Franz Mayer Museum), Appearance of the Virgin to Saint Peter Nolasco (private collection), Vision of Saint Peter Nolasco and Appearance of Saint Peter to Saint Peter Nolasco (both in the Prado Museum), the Discovery of the Virgin of Puig (Cincinnati Museum of Art) and The Surrender of Seville (collection of the Duke of Westminster). The Nativity of San Pedro Nolasco (Museo de Bellas Artes de Bordeaux), also belonging to this series, is of doubtful attribution, with the remaining canvases, preserved in Seville Cathedral, being attributed to Francisco Reina.

Library

Zurbarán painted a series of portraits of theologians and preachers of the Mercedarian order for the convent library, four of which are in the San Fernando Royal Academy of Fine Arts. Another canvas with similar characteristics (sacristy of the church of Santa Bárbara in Madrid) may come from the same set.

Convent of San José de la Merced Descalza (Seville)

For this convent —now disappeared— Zurbarán made ca. 1636 various canvases. The original location of some is unknown, due to the reforms carried out, the Napoleonic looting and the dispersion due to the confiscation. On opposite sides of the transept of the convent church were San Lorenzo (Hermitage Museum) and San Antonio Abad (private collection). They have also reached our days: Saint Joseph with the Child Jesus (Church of Saint Medardo, Paris), Saint Apollonia (Louvre Museum), Saint Lucia (Chartres, Musée des Beaux-Arts), Burial of Saint Catherine (Old Art Gallery in Munich) and The Eternal Father (Museum of Fine Arts in Seville).

Dominican Order

Santo Tomás College (Seville)

Like other orders of the 17th century, the Dominicans founded a college next to the convent. For the altarpiece of the main altar of the conventual church, Zurbarán painted in 1631 his magnificent canvas Apotheosis of Santo Tomás de Aquino (Museo de Bellas Artes de Sevilla), sometimes considered his masterpiece. It is known that he also painted a series of six half-length saints for the predella of the altarpiece, from which perhaps come a Saint Peter the Martyr and a Dominican Friar Reading, both today in private collections. A Saint Andrew (Budapest Museum of Fine Arts) and The Archangel Gabriel (Fabre Museum) surely come from the Flemish Chapel. There are two versions of Fray Diego de Deza, perhaps coming from this school, one from the prior's cell and the other from the library.

Convent of San Pablo el Real (Seville)

In 1626, those responsible for this convent commissioned twenty-one paintings from Zurbarán, fourteen of them on the life of Saint Dominic, four on the doctors of the Latin Church, and three more, corresponding to Domingo de Guzmán, Tomás de Aquino and Saint Buenaventura.. Currently, the series on Saint Dominic seems to have disappeared, and of the group of ecclesiastical doctors only three survive: San Gregorio, San Ambrosio and San Jeronimo, all three in the Museum of Fine Arts in Seville.

Sacristy

As a complement to the series of twenty-one paintings, Zurbarán painted in 1627, for the sacristy, the impressive Crucified, signed and dated, which earned him great prestige among almost all the religious orders of Seville.

Church of Santa María Magdalena (Seville)

In this church —belonging to the convent of Saint Paul— Saint Dominic in Soriano and the miraculous healing of Blessed Reginald of Orleans are preserved, which perhaps were part of the cycle on Saint Dominic.

Porta Coeli Convent (Seville)

For the church of this convent —destroyed in the XIX century— Zurbarán produced two canvases, between 1638 and 1640: a San Luis Beltrán and a Blessed Enrique Susón, both currently in the Museum of Fine Arts in Seville.

Trinitarian Order

The Trinitarians had the Convent of the Trinity in Seville, for which Zurbarán undertook —in 1629— to paint several works, charging 130 ducats, which is very little and explains the broad participation of the workshop. The following works come from this convent:

Altarpiece of Saint Joseph

The canvases from this altarpiece, of poor quality, are the work of the workshop. They are Jesus Among the Doctors (Seville Museum of Fine Arts) and Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple (El Escorial Monastery)

Sanctum

The magnificent Blessing Child Jesus (Pushkin Museum) comes from the door of the tabernacle, a safe work by Zurbarán and one of his few panel paintings.

Franciscan Order

The Franciscan order, founded by Saint Francis of Assisi in 1209, is divided into three branches: Friars Minor, Friars Minor Conventual, and Friars Minor Capuchin. Zurbarán worked for two of these three Franciscan branches.

Convent of the Capuchins (Seville)

Zurbarán painted two versions of the Crucified One for this convent, one ca. 1625-1630, and another ca. 1640. Both are currently in the Museum of Fine Arts in Seville.

San Buenaventura College (Seville)

The convent of the younger brothers was one of the most important in Seville and its college was the Spanish center for theological studies of this order. In 1629, Zurbarán and Francisco Herrera el Viejo began a pictorial cycle on the life of Buenaventura de Fidanza for the church of the convent. Francisco Herrera made four canvases —on the gospel wall— representing the youth and vocation of Saint Buenaventura, while Zurbarán made another four —on the epistle wall— representing the maturity and death of said saint. The works carried out by Zurbarán are: Saint Buenaventura reveals the crucifix to Saint Thomas Aquinas (destroyed in Berlin in 1945). Exhibition of the body of Saint Bonaventure and Saint Bonaventure at the Council of Lyon (both in the Louvre Museum) and Saint Bonaventure in prayer (Old Master Paintings Gallery)

Order of Carmelites

The order of Our Lady of Mount Carmel arose in the 12th century when a group of hermits, inspired by the prophet Elijah, withdrew to Mount Carmel, where they followed the Rule of Saint Albert. Considering its origin in the Holy Land, it is understood that the Carmelite monks commissioned the painter to represent certain saints rather typical of Eastern Christianity.

Carmelite Church of San Alberto (Seville)

The Church of San Alberto had seven side chapels, each with an altarpiece. Zurbarán was commissioned —ca. 1630-1635—of the decoration of the last chapel on the epistle side, of which Saint Peter Thomas and Saint Cyril of Constantinople have been preserved, both now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, San Blas. (National Museum of Art, Bucharest) and Saint Francis of Assisi (Saint Louis Museum of Art). Two paintings dedicated to Saint Peter and Saint Paul have disappeared.

Order of Carthusians

Cartuja de Santa María de la Defensión (Jerez de la Frontera)

The charterhouse of Jerez de la Frontera, founded in 1476, owes its name to a miraculous apparition of the Virgin in 1370 in which Mary would have revealed the place where the Castilians had fallen into an ambush set up by the Moors, thus freeing them from certain death and defeat.

Central altarpiece

Zurbarán painted eleven paintings for the altarpiece of the high altar, commissioned in 1636 and completed between 1639 and 1640. In the central compartment was the Apotheosis of Saint Bruno (Cádiz Museum). On the predella were San Juan Bautista and San Lorenzo currently in the Museum of Cádiz, where there were also four small canvases whose location in the altarpiece is doubtful. The rest are outside of Spain, four of them in the Grenoble Museum: The Annunciation, Circumcision of Jesus, Adoration of the Shepherds, and Adoration of the Magi, and The Battle of Jerez in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Access to the tabernacle

In the charterhouses, the tabernacle is located in a chapel behind the main altar, which is accessed by a corridor. For this access, Zurbarán produced ten paintings: two Ángeles turiferarios and eight Carthusian Saints. These works are painted on panel, an unusual fact in Zurbarán, and are in the Museum of Cádiz except for the one of a Carthusian, currently missing.

Choir of lay brothers

Two important canvases come from this choir: Virgin of the Rosary with two Carthusians (National Museum of Poznań) and —probably— Immaculate Conception with Saint Joachim and Saint Anne (National Gallery of Scotland)

Charterhouse of Santa María de las Cuevas (Seville)

For the new sacristy —which still exists— of this convent, Zurbarán made three canvases: Saint Hugo in the Carthusian refectory, Saint Bruno's visit to Pope Urban II, and the Virgin of the Carthusians. Its date of realization is doubtful: according to some authors it is ca. 1655, and according to others it is ca. 1630-1635. A version of Rest on the Flight into Egypt (currently destroyed) and the Child with the Thorn in the Museum of Fine Arts in Seville also seem to come from this charterhouse.

Jerónimo Monastery of Guadalupe

According to legend, a shepherd found a statue of the Virgin next to the Guadalupe River, hidden by the Visigothic Christians to avoid its desecration. Considering that the invocation of this image had led to his victory in the battle of Salado, Alfonso XI of Castile ordered the construction of a sanctuary in the place of discovery. In 1389, King Juan I of Castilla ordered its expansion and its delivery to the order of San Jerónimo. Commissioned by those responsible for the Zurbarán monastery, he painted eleven paintings —between 1639 and 1645— that make up his only complete pictorial series conserved in situ. There is also another set in the laymen's choir, considered the work of his workshop.

Sacristy

In the sacristy are paintings related to Hieronymite monks. The first —Misa del padre Cabañuelas— was possibly a test of ability, since it is signed and dated 1638. The others —some dated 1639— are considered to have been made between this date and 1645, and are: Fray Diego de Orgaz chasing away temptations; Fray Andrés de Salmerón comforted by Christ; Fray Gonzalo de Illescas, Fray Fernando Yáñez refusing the archiepiscopal mortarboard of Toledo; The vision of Fray Pedro de Salamanca; Fray Martín de Vizcaya distributing alms and Farewell to Father Juan de Carrión.

Chapel of Saint Jerome

In the adjacent chapel of Saint Jerome there are three canvases alluding to the life of this saint. In the attic is The Apotheosis of San Jerónimo, also called "the Pearl of Zurbarán". On the right side are The Temptations of Saint Jerome and, on the left, Saint Jerome scourged by angels. All three works are dateable ca. 1640-1643

Choir of lay brothers

The works in this choir—dating ca. 1658 and 1660—are generally considered the work of a workshop. However, after a restoration in 1965-1966, San Nicolás de Bari and the Imposition of the Chasuble on Saint Ildefonso have revealed to be of high quality, and modern criticism attributes them to the late period of Zurbarán himself.

The royal commissions

In 1634, Zurbarán was in Madrid and was invited by the king to decorate the Salón de Reinos of the new royal palace of Buen Retiro, together with other painters —including Velázquez—. Of the twelve military victories of the kingdom, he painted one; The Defense of Cádiz against the English (Museo del Prado). He also illustrated ten episodes from the life of Hercules (Museo del Prado), mythical ancestor of the Spanish branch of the Habsburgs. These paintings, painted to the greatest glory of Felipe IV and Olivares, certainly do not constitute the best of his work, since the hero had to be represented half-naked, and Zurbarán did not master anatomy, due to the majority of his religious production..

Individual commissions

Leaving aside the representations of the Virgin martyrs, which will be discussed later, it is necessary to note that the works intended for individuals are more repetitive than the works intended for convents. Jonathan Brown writes, somewhat ironically, that, on account of his name, "the artist's studio was a kind of office for devout paintings ". (Catalogue of the 1988 exhibition of the Grand Palace, p.36).

The Marian theology of Seville: The Immaculate Conceptions of Zurbarán

The Immaculate Conception was the favorite subject of the Sevillians of that time. There was still discussion about this Marian dogma. The debate centered on whether the Virgin Mary had been conceived without original sin weighing on her, or had been conceived like all human beings, marked, from conception, with original sin, and would have been purified by God when He was still in his mother's womb. The doctrine of the Immaculate Conception was opposed to the doctrine of sanctification. There was discussion on this point in the streets of Seville, and a riot almost broke out when a Dominican preached the doctrine of sanctification. The Spanish sovereigns asked the Pope to take sides in favor of the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception. Zurbarán's works, such as the Immaculate Conception of Barcelona (1632) illustrate this position, which was not a dogma of faith for Catholics until the 19th century.

Torment and modesty: The Saints of Zurbarán

In opposition to the Rhenish painters, who maintained that the sight of blood was necessary for the exaltation of the soul, Zurbarán did not take pleasure in the display of wounds and treated the torments associated with them with great modesty. He considered that it was not necessary to stimulate the murky sadistic passions of the viewer. Trying to harmoniously combine his pictorial investigations and his spiritual meditations, Zurbarán devoted himself to this theme of the virgin martyrs so appreciated in Seville at the beginning of the century. Zurbarán's saints are not the means to represent the instruments of torture through conventional and bland poses. Quite the contrary: the expression of his virgins denotes, only, the suffering that must be felt in those terrible moments.

Without a doubt, there has never been a desire to represent, in the plastic arts, the psychic suffering of women who were, really, as martyred as men. The few exceptions that can be found in medieval statuary represent, rather, the symbol of the sinful woman (lust punished with hell, for example). Perhaps the artist yielded to the wishes of the women: to be represented with a careful image, since, at that time, they could not take care of themselves

Santa Águeda

After the Council of Trent, Cardinal Paleotti commissioned painters to paint seven saints, including Saint Agatha. Roman laws forbade killing young virgins; A Sicilian prefect, unable to seduce or violate the miraculously protected virginity of Saint Agatha, made him cut off her breasts and imprisoned her. Saint Peter appeared to the young woman and healed her wounds.

Due to the nature of her torture, this saint only appears, in the background, in three paintings from the Golden Age. But both the Order of Mercy and the hospital convents wanted to have an image of her: Santa Águeda, patron saint of the nurses, pious helper of lactation, the one who could ensure the subsistence of the weakest and the poorest.

Paul Valéry felt great admiration for this Saint Águeda exhibited in the Fabre Museum (Montpellier) which probably came from the Merced Calzada convent. Plump, like the Madonnas of the French XVI century, the young woman presents her breasts placed on a tray, without any ostentation, showing them with a simple and dignified gesture. With a lot of contrast and without modeling, the work may belong to Zurbarán's tenebrist period.

Saint Margaret

This painting is very different from the previous one, although the eyes and features of the face made some critics think that it was the same model that was used to paint Santa Águeda. Zurbarán represents Santa Margarita with the lines of an elegant shepherdess. The cane that she holds in her hand, which could pass for a staff if it were not finished with a hook, and the disturbing presence of a dragon, to her left, lead us to think that it is a tragedy.

"This beautiful pastor, with a very affected posture, seems to come from a theatrical scene. In fact, in many of the processions or the sacramental cars carried out during the week of the Corpus Christi, some historians make this saint appear, as well as in the comedies of the saints represented in the corralas (recinth in which comedies were represented) of Seville, and, perhaps, Zurbarán was inspired by these images. The heroines are always very young and beautiful, such as the Santa Juana de Tirso de Molina, or the Santa Margarita de Diego Jiménez de Enciso. His beauty is described as a gift from heaven, a reflection of the soul that mysteriously shines and attracts, irresistibly, all hearts." (Catalogue of the Zurbarán exhibition by Odile Delenda of 1988, p. 275).

It is comforting to see an artist from the 17th century, where some wanted to pass spirituality off as self-righteousness, that we offers this Mary of Antioch who anticipates the other shepherdesses who are, on occasion, virgin martyrs of the Bavarian baroque as can be seen, for example, in the churches of the Vierzehnhiligen —providing the treatment of the fabrics with the mime of a Memling in the work The Mystical Marriage of Saint Catherine (Memling Museum, former Saint Jean Hospital).

The master of animal and still life paintings

The term still life —or still life— is an artistic genre that represents animals, flowers and other objects —natural or man-made— either in paintings without characters, or as part of a religious painting, history, genre, or other types of compositions with characters. Zurbarán was a magnificent still life painter of both categories. Animal painting is a separate case because —since it can represent live animals— it cannot be considered a "still life".

Animal painting

The animals can be part of a composition, or they can be represented in a painting without characters. In the first case, Zurbarán produced magnificent examples such as the departure from San Pedro Nolasco to Barcelona. An example of the other case is the Agnus Dei—there are six autograph versions—where the representation of the wool achieves an almost tactile sensation, and this simple theme achieves a transcendent quality.

Still lifes without characters

The catalog raisonné of Zurbarán's works —carried out by Odile Delenda— reviews eight still lifes by Zurbarán, which make up a gallery of different shapes, sizes and materials, treated with great care. Nothing distracts the viewer's attention, since the objects are presented against a dark background, and the light highlights their curves and volumes, creating different effects depending on each material. Generally, Zurbarán values objects individually, juxtaposing them in the whole.

The five canvases: Still Life with Pots, Fruit, Gherkin, and Peppers, the Still Life with Quinces, the Basket of Apples and Peaches, Sweets on a Silver Plate, and the Cup of Water and Rose on a Silver Plate are not works completely unsure of the master, and may be fragments of larger compositions now lost.

The only signed and dated still life is the Still Life with Citrons, Oranges, and Rose (Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena), which depicts four citrons on a plate, six oranges with their leaves and flowers, a cup on a saucer metallic with a rose on the edge.

There are two magnificent, almost identical versions of the Still Life with Pots: one in the Prado Museum and the other in the MNAC in Barcelona, both donated to these museums by Francesc Cambó. The four objects are arranged on the same plane, aligned in an almost "ceremonial" manner. The cup on the left is made of golden metal, and the other three vessels are made of clay. Those at both ends rest on tin trays. The composition produces an impression of simplicity—not emptiness—asceticism without severity, rigor without rigidity.

Still life in compositions with characters

Throughout his career, Zurbarán took special care in the representation of objects, in compositions with characters. In his first Miraculous Healing of Blessed Reginald of Orleans (1626) he already painted a plate with a cup, and in his last known work —The Virgin with Child and Saint John, (1662)— he represented some fruits in a tin dish. In all of these still lifes he carefully represented — lovingly, one might say — modest objects, endowing them with a symbolic quality. Antonio Bonet emphasizes that "his still lifes have a density, a fullness so vigorous that, although they are only one of the elements of a composition, their presence is imposed in the same way as the main scene".

The sewing kits of the Virgin

The basket of linen appears constantly in Zurbarán's representations of the Virgin's childhood and youth, showing that in a certain way Salvation depended on Her. The painter based himself on sources such as the Gospel of the pseudo-Matthew, and on the recommendations of Pacheco, who comments: & # 34; Having collected her work at nightfall, the Virgin leaves her sewing in a basket, at night. feet of her & # 34;. The white clothes sewing kit is a sign of humble labor and a prefiguration of the Shroud, and can be seen in The Grenoble Annunciation, the Virgin Child in Ecstasy (Metropolitan Museum of Art), or in the three autograph versions of The House of Nazareth.

The table of the Carthusians

In the large canvas San Hugo in the refectory of the Carthusians, Zurbarán composed the largest of his still lifes. Saint Bruno and six other Carthusians are seated at an L shaped table, before which Saint Hugo is represented —on the left— and a page in the center. The L-shaped arrangement of the seated Carthusians and the hunched body of Saint Hugh avoid the sensation of rigidity, which could be derived from the composition. In front of each monk the corresponding clay bowls are arranged, with food and a few pieces of bread. Two clay jugs, an upturned bowl and some knives make up a set that could be monotonous if it weren't for the peculiar shape of the table, and because the objects have different distances in relation to the edge of the table. The two jugs are from Talavera and show the arms of Gonzalo de Mena, founder of the Monastery of La Cartuja, where this canvas comes from.

Eating in Emmaus

In this painting, everything is designed to draw attention to the symbolism of the Supper at Emmaus. The composition focuses on the table, which attracts the viewer's attention, contrasting with the characters located in the shadows. As usual in Zurbarán's still lifes, the objects are almost aligned. On a carefully unfolded white tablecloth, bread is represented, a varnished clay jug, two plates with food and a foreshortened knife, which accentuates the perspective. The piece of bread that Christ has just opened, an even whiter color than the tablecloth, attracts the eye. The other objects on the table acquire an intense hue, due more to the glow of the bread than to the light coming from the left.

Conclusion

His appreciation grew after his death and his popularity went beyond the borders of Spain. Napoleon's younger brother, the unpopular José Bonaparte, compassionately called the intruder king or, contemptuously, Pepe botella, sent to Paris for the Napoleon Museum, some of Zurbarán's greatest works. Many generals of the Empire, and even Marshal Soult, took several of those paintings taken from Seville after the closure of the convents:

But why will they buzz? More than the avidity of the new rich, could it be thought that “these men, in general from the people and without artistic culture, felt a spontaneous attraction towards this simple, warm and direct painting that could awaken, in some of the main admirers of Zurbarán (the Soult Marshal, General Darmagnac), some memories of his Languedocian childhood or Gascona.» (Paul Guinard, Trés

From 1835 to 1837, Luis Felipe sent Baron Isidore Taylor, Royal Commissioner of the French Theater, to Spain to gather a collection of works by Zurbarán that were scattered about. Despite his 121 paintings, Zurbarán was, however, less appreciated than Murillo. He was only judged from a romantic point of view, considering him, above all, as the Spanish Caravaggio, painter of monks. His Kneeling Saint Francis with a Skull, powerfully drew attention.

- «Moines de Zurbaran, blancs chartreux qui, dans l'ombre,

- Glissez silencieux sur les dalles des morts,

- Murmurant des Pater et des Ave Saint name,

- Quel crime expiez-vous par de si grands remords?

- Fantômes tonsurés, bourreaux à face blême,

- Pour le traiter ainsi, qu'a donc fait votre corps?»

- «Monjes de Zurbarán, white cartujos that, in the shadow,

- You pass silently on the slabs of the dead,

- Murmuring the Pater and the Birds without a name,

- What crime do you make for such great remorse?

- Phantoms tons, pale greens

- To treat it so what has your body done?"

Written by Théophile Gautier, in his selection Spain of 1845. Curiously, this Zurbarán, a gloomy painter of tormented faith, is also Élie Faure's:

"The sterility of Spain is, in the burying cloisters in which meditation is exercised with the skulls of the dead and the fur-covered books. The grey or white vestments, long and tetheric as the sweatshops. The vaults are thick, the cold slabs, the purple light. A red tapestry, or a blue sprain, animate, here or there, this aridity. The will to paint is revealed in the hard bread, the raw roots of the food taken in silence, one hand, the earthy face, everyvérica, a silvery purple tablecloth. But those spectral faces, those matt garments, that sober wood, those naked bones, those unglossed ebony crosses, those ochre books with a red strip, ordained and sad like the hours that are volatilized, lost in taciturous repeated exercises up to the last moment, take the appearance of an implacable architecture that the same faith imposes on the plastic line, prohibiting all Those who distribute or take food have the need to live on a solemnity that passes the tablecloth, the vessels, the knives and the sustenance. Those who are on the funeral bed print the life that surrounds them the stiffness of death." (Modern art, reissue of 1964, pp. 164-166).

Zurbarán became famous before he was thirty, especially after painting his cycle of La Merced Calzada, a commission that Alonso Cano, a master painter since 1626, had rejected.

Fortunately another one in the XX century about the painter from Extremadura. Forgetting the pietist aspect, exaggeratedly emphasized, Christian Zervos (1889-1970), who was director of the Cahiers d'art (Art Notebooks) and a great connoisseur of painting of his time — as well as Greek Art and Prehistoric Art—, editor of a raisonné catalog of Pablo Picasso's work, recognizes that Zurbarán must be given a preponderant place in Spanish art:

"Excepting the El Greco, and perhaps also Velázquez, who is equal, but superior, Zurbarán overcame all the other Spanish painters. In addition, his work has a lot to do with the current trends in painting. However his work is not known or appreciated in its fair measure, (...). The characteristic of Zurbarán's work is to show everything that painting can offer regarding human reality, (...). Zurbarán presents his saints and his monks in the most concise psychic life, but at the same time more tormented by the serious spiritual concerns caused by the desire to approach God. He does not express, in his paintings, any terrible feeling. Death has no frightening for him." (Citated in the 1988 Exhibition Catalogue, p. 53).

Zervos talks about the topicality of Zurbarán's painting. This is so, if one analyzes the treatment given to the clothing of Saint Andrew (Budapest), to the cloak of Saint Joseph (The walk of Saint Joseph and the Child Jesus, a masterpiece found in the church of Saint Medardo (Paris), and the habit of Blessed Saint Cyril (Boston), it is understandable that some critics speak of a "sought-for stylization, premonitory of Cubist abstraction" (1988 exhibition catalog, p. 156). And isn't the still life of the Disciples of Emmaus closer, in its rigor, to that of Cézanne's Still Life of the Casserole? (Orsay's Museum)?

Like all teachers, Zurbarán, does not give the impression that it has conformed and limited to the requirements required by the orders. Second-order artists say, loud and clear, that the genius lies in freedom of expression and that being free is not obeying anyone. Lamentable explanation of the freedom that condemns, in fact, to be the servant of his desires, of his passions and, even, of his impulses. To all this we must oppose the genius of a Zurbarán for which real freedom consists in transcending prohibitions, rules (without disdaining them), and transforming all demands on the occasion conducive to creating a masterpiece. This attitude of not enslaving itself to the rules (slavery to which the mediocre spirits adhere) is the germ of creation, which is also found in Jean Racine.

But, when one has reached the top, one should not raise the question of hierarchies among the great painters. To recognize geniuses it would be necessary to believe oneself superior to them! The best thing that can be done is to meditate on the works, try to understand the problems they faced and reflect on the importance that their works may have had in the history of art. El Greco, Zurbarán, Velázquez, Murillo, are not competitors, or are in competition, each one, in their own way, has the particular criteria that each one has about art, people and things.

On this point, listen to Ives Bottineau, general inspector of the Museums of France, in charge of the National Museum of the Palace of Versailles and the Trianon:

- "Nowadays, according to a regular balance in the history of art, some commentators, at least in private, disdain Zurbarán's admirers compared to Murillo's poetic ease. But Spanish painting is so rich that the recognition given to its greatest representatives should not conform to the Mudable classification of taste and criticism; rather, follow the paths of enlightening and admirative prudence. Each of them, of the great, deserves one to murmure, in this respect, the principle of John Keats' verses in the Endimion:

- A thing of beauty is a jewel for ever:

- Its loveliness increases; it will never

- Pass into nothingness...»

- A thing of beauty is a jewel for ever:

- (The beautiful is joy forever:

- His charm grows and never returns to nothing...)

- (The beautiful is joy forever:

(Exhibition catalogue, 1988, p. 55).

Paintings

References and notes

- ↑ «Zurbarán, Francisco de - Museo Nacional del Prado». www.museodelprado.es. Consultation on 17 March 2017.

- ↑ Delenda. Francisco de Zurbarán, Catalogue Reasoned and Critical. pp. 53 and 54.

- ↑ Alcolea. Zurbarán. pp. 9 and 13.

- ↑ Delenda, Odile. Francisco de Zurbarán, Catalogue Reasoned and Criticalp. 58.

- ↑ Alcolea. Zurbarán. pp. 84-85.

- ↑ Delenda. Francisco de Zurbarán, Catalogue Reasoned and Criticalp. 66.

- ↑ Alcolea. Zurbarán. pp. 86-87.

- ↑ Alcolea. Zurbarán. pp. 102-103.

- ↑ Alcolea. Zurbarán. pp. 120-121.

- ↑ Official Museum Page

- ↑ Trying to dismember Zurbarán (comparing it with Velázquez, for example), by classifying it as a simple hagiographer to use and according to the time, would be a tremendous mistake. This is as true as the fact that the production of your workshop was not always the same. During the 1630s the costly wars, the provincial revolts and the unfortunate attempts made to try to straighten the Spanish economy impoverished Spain. The Andalusian commissions decreased and the Zurbarán workshop was dedicated to the export of its paintings to South America. Dozens and twenties were sent: The twelve sons of Jacob (where, it is not known why, they wanted to see the ancestors of the natives); The twelve Caesarsand numerous paintings of saints and founders of various orders. Customers weren't, indeed, some tins and anyway... they were far away!

- ↑ Alcolea. Zurbarán. pp. 122 and 123.

- ↑ Serrera, Juan Miguel. They'll buzz. Catalogue of the exhibition held at the Museo del Prado, May-July 1988. pp. 63-84.

- ↑ The Mail (30 March 2011): “To the rescue of the Jewish legacy of Zurbarán in England”

- ↑ El País (19 February 1995): “Zurbaran returns to Spain with his Jacob series”

- ↑ Delenda. Francisco de Zurbarán, Catalogue Reasoned and CriticalP. 100.

- ↑ Baticle. They'll buzz. Catalogue of the exhibition held at the Museo del Prado, May-July 1988. pp. 137-147.

- ↑ Baticle. They'll buzz. Catalogue of the exhibition held at the Museo del Prado, May-July 1988. pp. 147-149.

- ↑ Baticle. They'll buzz. Catalogue of the exhibition held at the Museo del Prado, May-July 1988. pp. 209-225.

- ↑ Peman. Zurbarán and other studies on painting of the XVII Spanish. pp. 41-44.

- ↑ Baticle. Catalogue of the exhibition held at the Museo del Prado, May-July 1988. p. 177-183.

- ↑ Baticle. Catalogue of the exhibition held at the Museo del Prado, May-July 1988. pp. 117-122.

- ↑ Delenda. Francisco de Zurbarán, Catalogue Reasoned and Critical. pp. 96 and 97.

- ↑ Delenda. Francisco de Zurbarán, Catalogue Reasoned and Critical.

- ↑ Delenda. Francisco de Zurbarán, Catalogue Reasoned and Critical. pp. 167 and 169.

- ↑ Delenda. Francisco de Zurbarán, Catalogue Reasoned and Critical. pp. 139 and 140.

- ↑ Peman. Zurbarán and other studies of painting of the XVII Spanish. pp. 95-118.

- ↑ Delenda. Francisco de Zurbarán, Catalogue Reasoned and Critical. pp. 415-419.

- ↑ Baticle. They'll buzz. Catalogue of the exhibition held at the Museo del Prado, May-July 1988. pp. 297-320.

- ↑ Royal Monastery of Guadalupe (ed.). «Real Monastery of Guadalupe». Consultation on 18 February 2026.

- ↑ Delenda. Francisco de Zurbarán, Catalogue Reasoned and Critical. pp. 437-458.

- ↑ Peman. Zurbarán and other studies on painting of the XVII Spanish. pp. 219-223.

- ↑ Bonet. "Zurbaran." Universal Encyclopedia. p. 271.

Contenido relacionado

Cathedral of Sevilla

Marcel Duchamp

U2