Four noble truths

The four noble truths are considered the central foundation of the Buddha's teachings. Its fundamental importance is reflected in the fact that it is present in all or almost all Buddhist traditions or schools from the first schools of early Buddhism to the present day. The different versions that can be found of the four noble truths generally follow the same content and form, suggesting that they all come from the same original source of teachings. Most scholars of the various Buddhist sources (in Pali, Sanskrit, Chinese, and Tibetan) agree in the general opinion that a Pali-language record could more likely be the original source of this teaching.

Due to the complexity and length of the topic of the four noble truths, it is difficult to express in a few words what the topic of this teaching is. Each author, scholar, and commentator expounds it from various points of view that may be equally valid. Venerable Ajahn Sumedho summarizes the theme of the four noble truths as follows: "that the unhappiness of humanity can be overcome by spiritual means."

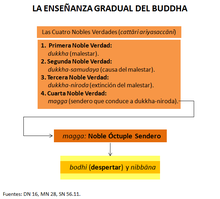

In summary, the four noble truths are: (1) the truth of discomfort, (2) the truth of the cause of discomfort, (3) the truth of the cessation or extinction of the cause of discomfort, and (4) the truth of the path that leads to the extinction of discomfort. In the Pali texts the key word is dukkha, a general term for “discomfort”, being the antonym of sukha (well-being). In the various translations, the word dukkha is translated by a variety of similar terms: pain, suffering, grief, grief, anguish, stress, dissatisfaction, discontent, etc., while sukha i> is translated as happiness, bliss, pleasure, joy.

Different Buddhist traditions give a central place to the four noble truths in the sense that they represent the enlightenment itself or Awakening (bodhi) of Gotama Buddha, the initiator or founder of Buddhism. As Jean Boisselier sums it up, the knowledge of the four noble truths is what made Prince Siddhartha Gautama the Buddha, the Awakened:

“From this moment [the third watch on the night of his enlightenment, the Buddha] possesses the Four Noble Truths ―truth about pain, truth about the origin of pain, truth about the cessation of pain, truth about the eightfold path (whose eight branches symbolize the attainment of the eight perfections) that leads to the cessation of pain―, and by that fact he becomes a Buddha."

Origin of the four noble truths

According to the oldest records of Buddhist scriptures, the four noble truths are mentioned and explained in a variety of sutta (discourses). For example, in the Páli Canon, the four noble truths are mentioned and/or explained in discourses number 16 of the Digha Nikaya, number 28 of the Majjhima Nikaya and number 56.11 of the Samyutta Nikaya. However, there seems to be general agreement that the Samyutta Nikaya discourse number 56.11 records the first time the Buddha expounded the teaching of the four noble truths.

This speech is known as the First Benares Sermon, being delivered, according to the Páli Canon, in the city of Varanasi (in Páli), present-day Benares. This sermon is also called "the setting in motion of the wheel of the law", an expression that appears both in the Lalitavistara and in the commentaries in the Pali language. Sermon or discourse number 56.11 of the Samyutta Nikaya is actually titled in Pali Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta, which literally translates to Setting In Motion (pavattana) Discourse (sutta). ) of the Wheel (cakka) of the Dhamma. who practiced certain meditative exercises before the attainment of enlightenment. This is referred to in the expression “the Exalted One addressed the group of five monks” that is read at the beginning of the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta.

The name of the four noble truths in the Pali language (cattári ariyasaccáni) suggests that the four truths are noble because they belong to or are known to the Noble Subjects (ariya), those who have achieved any of the four levels of Awakening. The adjective sacca, which is usually translated as “true”, also means “real”, suggesting that the four truths are not categorical philosophical statements of the Buddha in the sense that they alone are the truth., or only they are true, but that they are the reality, the real or true experience, of the Noble Subjects.

The Four Noble Truths in the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta

In the Pali language texts, the four noble truths are as follows. It is important to highlight that the Buddha explains each one of them in more detail and length in other discourses of the Canon and that, in addition, the contents of each one of them are understood within the general framework of the Buddhist theory of rebirth (bhava) and kamma (karma in Sanskrit).

1- The truth of dukkha: Discomfort in all its forms (pain, suffering, grief, grief, anguish, stress) is inherent to existence in the world, that is, in any of the 31 planes of existence of samsára:

This, O monks, is the Noble Truth of Suffering. Birth is suffering, old age is suffering, disease is suffering, death is suffering. Pity, regret, pain, distress, tribulation are suffering. Associating with the undesirable is suffering, separating from the desirable is suffering, not getting what one desires is suffering. In one word, the five aggregates of attachment to existence are suffering.

This statement does not deny the happiness or bliss (sukha) that are possible in existence: it only points out in detail where dukkha lies in mundane existence. The first four processes are frequently mentioned by the Buddha in other texts as a general description of mundane existence: being born, growing old, getting sick, dying. The following three situations have to do with the mental poisons of desire (lobha) and hate (dosa) and the expectations that the unawakened mind builds from them.: being attached to what is despised or hated, being separated from what is appreciated or loved, not getting what we want. The expression "five clinging aggregates" refers to the notion pañcakkhanda, also translated as five clinging aggregates and five existence aggregates, refers in the Buddha's philosophy to the five sets of psycho-physical processes. physiques that constitute what we call a human being. The dukkha characteristic is also inherent in these five aggregates.

2 - The truth of the cause (samudaya) of dukkha: The key word in the second truth is the term tanhá, which is usually translated as desire but also means thirst, lust, and attachment. The Buddha also mentions here three specific types of tanhá:

This, O monks, is the Noble Truth of the Origin of Suffering. It is this desire that generates new existence, that associated with pleasure and passion is delighted here and there. That is, sexual desire, desire for existence and desire for non-existence.

Sexual desire or thirst is kama-tanhá (do not confuse kama, sexuality, with kamma, intentional action): it is the desire or lust associated with the six “objects” of the senses (vision, hearing, smell, taste, touch, and intellect). The desire or thirst for existence is bhava-tanhá: it is the desire to be born and reborn, to be this or that, to live or exist on a certain plane of existence. And the desire for non-existence is vibhava-tanhá: it is the desire for the annihilation of the being and the present existence of the being, the desire to end this or that, to end existence. Sexual desire and the desire for existence lead to clinging, to attachment. The desire for non-existence does not lead to attachment but it does lead to a destructive attitude towards life, which, according to the Buddha, also produces more rebirth (bhava) and more discomfort (dukkha ) for being in the future.

3 - The truth of the extinction (nirodha) of dukkha: By determining the cause of the discomfort of existence, we can exterminate that cause, whereupon its effect ceases. If the cause of dukkha is tanhá, then the extinction of dukkha logically comes with the extinction of tanhá:

This, O monks, is the Noble Truth of the Suffering Cessation. It is the total extinction and cessation of that same desire, its abandonment, its discard, liberation, not dependence.

The extinction of desire comes with a long and delicate process of study, contemplation, reality assessment, reflection and meditation. For this the Buddha taught a large number of ethical practices and mental and spiritual exercises to achieve the proper and correct extinction of tanhá. However, the key word behind the third noble truth is not so much extinction as nibbána (nirvana in Sanskrit): the supreme state of total and final extinction of the three poisons mental (greed, hate, and ignorance). Nibbána, which means “extinguished fire”, is not the extinction of the being or non-existence: it is a state of supreme liberation where the being is no longer reborn again in samsára. Everything in samsára is perishable (anicca) and causes discomfort (dukkha), but beyond samsára (“the Other Shore”, as the Buddha calls it) there is the state of nibbána, which is non-perishable and the cause of supreme bliss. This truth indeed contains the most important point of all the Buddha's teaching, since nibbána is the object and end of all this Teaching and Discipline. The Supreme (nibbána) is in fact what gives meaning and purpose to the entire philosophy and religion of the Buddha, the fourth noble truth being nothing more than the training that leads to it.

4 - The truth of the path (magga) that leads to the extinction of dukkha: The last noble truth summarizes the training program that the Buddha taught to achieve the extinction of dukkha and attain the state of nibbána:

This, O monks, is the Noble Truth of the Path leading to the Cessation of Suffering. Simply this Noble Path Oil; that is, Recto Understanding, Recto Thought, Recto Language, Recta Acción, Recta Vida, Recto Esfuerzo, Recta Atención y Recta Concentración.

This is the famous Eightfold Path, as it is made up of eight factors. The Páli adjective sammá that precedes each of the factors has several translations, all valid: straight, correct, perfect, harmonious, beautiful. The adjective sammá means something complete, perfect, beautiful, without fault, without breaks. This suggests that the Buddha saw the eight factors of the path not as a categorical moral statement of the type "this is right and everything else is wrong" but as an exposition of those behaviors, conducts and states of mind that are beautiful, harmonious, complete, perfect. in themselves. However, it is also true that the eight factors are correct in the sense that they correct what is deviant, what is unskillful, what is obscure or crooked.

Traditionally the eight factors of the noble path are divided into three main sections:

- Wisdom or discernment (handkerchief): Right understanding (samma-ditthi), Correct Aspiration (samma-sankappa).

- Morality or virtue (Yeah.): Speak correct (samma-vaca), Correct Action (samma-kammanta), Fashion of Correct Life (samma-ajiva).

- Concentration (samadhi): Right effort (samma-vayama), Correct Attention (samma-sati), Correct Concentration (samma-samadhi).

The Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta does not explain in detail what each of the eight factors of the noble eightfold path mean. Such a detailed explanation appears in other discourses, such as Samyutta Nikaya No. 45.8 (Maggavibhanga Sutta, Path Analysis Discourse) where the eight factors are explained. as follows:

- Perfect views: knowledge about discomfort (dukkha, kamma), knowledge about the cause of discomfort (tanha, bhava), knowledge about the extinction of discomfort (Nibbana), knowledge about the path leading to the extinction of discomfort (yesla, handkerchief, samadhi).

- Perfect intention: intention of resignation (nekkhama), intention of benevolence (metta), intention of harmlessness (karuna and ahimsa).

- Talk perfect: refrain from false speech (Musavada veramani), refrain from defamatory speech (pisunaya cowya veramani), refrain from speaking hard (pharusaya cowya veramani), refrain from idle speech (samphappalapa veramani).

- Make perfect: refrain from taking life (panatipata veramani), refrain from taking what is not given (adinnadana veramani), refrain from wrong sexual conduct (kamesu miccha-cara veramani).

- Perfect livelihoods: gains must be acquired by legal means, peacefully, honestly, without causing harm or suffering to others. Incorrect work: arms trafficking, living beings, meat production, poisons and poisoning.

- Perfect effort: prevent the emergence of unsuccessful insanity mental states, abandon insanity mental states that have already arisen, cause unsuccessful healthy mental states to emerge, maintain and perfect healthy mental states that have already arisen.

- Perfect attention: practice of the four foundations of care (Cattaro satipatthana). This is contemplation of the body, contemplation of sensations in itself, contemplation of the mind itself, and contemplation of the mental qualities in themselves.

- Perfect concentration: All four jhana, meditative absorptions, which are, the first jhana (ecstasy and pleasure born of renunciation, accompanied by directed thought and evaluation), the second jhana (ecstasy and pleasure born of concentration, unification of the free consciousness of directed thought and evaluation; internal security), the third jhana (from which the Nobles declare: “Ecuánime and attentive, has a pleasant abode”), and the fourth jhana (the purity of equanimity and attention, neither pleasure nor pain).

Other interpretations and traditions

The Four Noble Truths express the basic orientation of Buddhism that we covet and are inclined to become attached to passing states and things that are unable to satisfy us and are painful (dukkha). This eagerness keeps us in samsara, the endless cycle of repeated rebirth and death and the dukkha that this entails. There is, however, a way to end this cycle, reaching Nirvana (spirituality), where attachment ends and where rebirth and dukkha do not reappear. This can be achieved by following the Noble Eightfold Path, restricting our adherences, cultivating discipline, and practicing meditation.

In summary form, the four noble truths are dukha, samudaya (ascension or going together), nirodha (cessation) and marga, the path to cessation.

In the Sutras (Buddhism), the Buddhist religious texts, the four truths have a symbolic function, as well as a proposition. They represent the awakening and liberation of the Buddha, but they also describe methods for sensitive people to free themselves from clinging to materialism. In the writings of the Pal Canon, the four truths appear as a network of teachings, as part of the Dharma that must be learned together. They provide the conceptual basis for introducing and explaining Buddhist thought, which must be fully understood and practiced.

The function of the four noble truths and their importance developed over time, when the liberating vision (Prajñāpāramitā-sūtra) gained a prominent position in the Sutras and the four truths came to represent this liberating vision, as part of the enlightened story of Buddha.

The four truths acquired particular importance in the Theravada tradition of Buddhism, indicating that their simple knowledge is liberating in itself. They are, however, less prominent in the Mahāyāna tradition, which considers the Bodhisativa Path (great spontaneous compassion) to be the central element of its teachings and practices. The Mahāyāna tradition interprets the four truths to explain how a liberated person can still be an omnipresent operative in this world. Western scholars who explored Buddhist concepts in the 19th century, as well as Buddhist Modernism, consider the four truths to be the basic and central teachings of Buddhism.

Some contemporary teachers tend to explain the Four Noble Truths from a psychological point of view, stating that dukha means mental anguish in addition to the physical pain of life, interpreting the four truths as the path to happiness. In the contemporary Vipassana movement, this concept emerges from Theravada Buddhism, which indicates that freedom and the pursuit of happiness are the main goals, not the end of rebirth, which it is barely mentioned in their teachings.

Contenido relacionado

Paul of Tarsus

Koran

Minerva