Formicidae

The ants (Formicidae) are a family of eusocial insects that, like wasps and bees, belong to the order Hymenoptera. Ants evolved from wasp-like ancestors in the mid-Cretaceous period, between 110 and 130 million years ago, diversifying after the spread of flowering plants across the world. They are one of the most successful zoological groups, with some fourteen thousand described species, although it is estimated that there may be more than twenty-two thousand. They are easily identified by their angled antennae and three-sectioned build with a narrow waist. The branch of entomology that studies them is called myrmecology.

They form colonies or anthills of a size that ranges from a few dozen predatory individuals that live in small natural cavities, to highly organized colonies that can occupy large territories made up of millions of individuals. These large colonies consist mostly of sterile wingless females that form castes of 'workers', 'soldiers' and other specialized groups. Ant colonies also have a few fertile males and one or more fertile females called "queens." These colonies are described as superorganisms, since the ants appear to act as a single entity, working collectively in support of the colony.

They have colonized almost every land area on the planet; the only places without indigenous ants are Antarctica and some remote or inhospitable islands. Ants thrive in most of these ecosystems and are estimated to form 15-25% of the biomass of terrestrial animals. There are an estimated one thousand trillion (1015) to ten one thousand trillion (1016) ants living on Earth. Their success in so many settings is considered to be due to their social organization and ability to modify habitats, their use of resources, and their defensive capabilities. Their long coevolution with other species has led them to develop mimetic, commensal, parasitic, and mutualistic relationships.

Their societies are characterized by the division of labor, communication between individuals, and the ability to solve complex problems. These parallels with human societies have long been a source of inspiration and the subject of numerous studies.

Many human cultures use them as food, medicine, and as an object of rituals. Some species are highly valued in their role as biological control agents. However, their ability to exploit resources brings ants into conflict with humans, as they can damage crops and invade buildings.

Some species, such as fire ants (genus Solenopsis), are considered invasive species, as they have established themselves in new areas where they have been introduced by chance.

Etymology

In Spanish, the word «ant» derives from the Latin formīca, which has the same meaning. It has the same origin as the corresponding words in other Romance languages, such as formiga (Portuguese, Catalan and Galician), fourmi (French) and formica (Italian). The family name, Formicidae, is also derived from the Latin formīca.

Taxonomy and evolution

| Aculeata |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The family Formicidae belongs to the order Hymenoptera, which also includes symphytes, wasps, and bees. The ants evolved from a lineage within the Aculate Hymenoptera, and a 2013 study suggests that they are a sister group to Apoidea. In 1966, E. O. Wilson and colleagues identified the fossil remains of an ant (Sphecomyrma) who lived in the Cretaceous period. The specimen, trapped in amber, dated to over 92 million years ago, had characteristics of both ants and wasps, but not found in modern ants. Sphecomyrma was probably a genus surface forager, while Haidomyrmex and Haidomyrmodes, related genera in the subfamily Sphecomyrminae, are considered active arboreal predators.

Following the expansion of flowering plants about 100 million years ago, they diversified and assumed a dominant ecological position about 60 million years ago. Some studies suggest, based on groups such as the Leptanillinae and Martialinae, which diversified from primitive ants that were likely to be predatory underground dwellers.

During the Cretaceous period, a few primitive ant species had a wide distribution on the supercontinent Laurasia (the Northern Hemisphere). They were sparse compared to other insects, making up about 1% of the insect population. Ants became dominant following adaptive radiation in the early Paleogene. During the Oligocene and Miocene they already represented 20-40% of all insects found in the main fossil beds. Of the species that lived in the Eocene, about one genus in ten survives today. The genera surviving today comprise 56% of the genera found in Baltic amber fossils (early Oligocene) and 92% of the genera in Dominican amber fossils (apparently early Miocene).

Termites, although they are also known as "white ants", are not really ants, as they belong to the order Isoptera and are therefore more closely related to cockroaches and mantises than to ants. The fact that ants and termites are both eusocial was motivated by a process of evolutionary convergence. Velveteen ants look like large ants, but are actually wingless female wasps.

Distribution and diversity

| Region | Number of species |

|---|---|

| Neotropic | 2162 |

| Neártico | 580 |

| Europe | 180 |

| Africa | 2500 |

| Asia | 2080 |

| Melanesia | 275 |

| Australia | 985 |

| Polynesia | 42 |

They inhabit all continents except Antarctica and a few large islands, such as Greenland, Iceland, and parts of Polynesia. The Hawaiian Islands also lack native ant species. They occupy a wide variety of ecological niches and are capable of exploiting a wide range of food resources acting as direct or indirect herbivores, predators and scavengers. Most species are generalist omnivores, but some are specialized feeders.

It is estimated that there are between one thousand billion (1015) and ten thousand billion (1016) ants living on Earth. Their ecological dominance can be measured by their biomass: estimates made in different environments indicate that they represent on average 15-20% of the total biomass of terrestrial animals, which rises to almost 25% in the tropics. According to these estimates, the biomass of all existing ants in the world would be similar to the total biomass of all human beings.

Its size ranges from 0.75 to 52 mm. The extinct Titanomyrma giganteum is the largest known giant ant, even larger than those of the genus < i>Dorylus, the largest currently extant giant ants, about 5 cm long, living in East and Central Africa; the fossil record indicates that males were about 3 cm long, but queens were as long as 6 cm, with a wingspan of about 15 cm.

Their color also varies; most are red or black, green is less common, and some tropical species have a metallic hue. Currently, some 14,000 species have been described, although it is estimated that there may be more than 22,000, with the greatest diversity located in the tropical zone. Taxonomic studies continue to develop their classification and systematics, and the databases Online ant species databases, including AntBase and Hymenoptera Name Server, help keep track of known and more recently described species. The relative ease with which The fact that ants can be collected and studied in different ecosystems has made them very useful as an indicator species in biodiversity studies.

Morphology

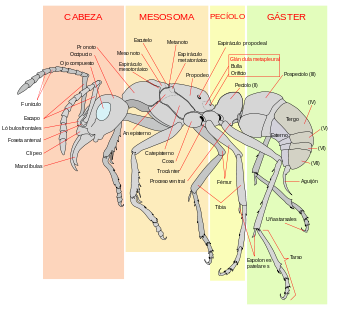

They have different morphological characteristics from other insects, such as elbow-shaped antennae, metapleural glands, and a strong constriction of their second abdominal segment into a node-shaped petiole. The head, mesosoma (the thorax plus the first abdominal segment, fused to it) and metasoma or gaster (the abdomen minus the abdominal segments of the petiole) are its three clearly differentiated body segments. The petiole forms a narrow waist between its mesosoma and the gaster. The petiole may be formed by one or two nodes (only the second, or the second and third abdominal segments).

Like other insects, ants have an exoskeleton, an outer covering that serves as a protective shell around the body and as an anchorage point for muscles, in contrast to the endoskeleton of humans and other vertebrates. Insects don't have lungs; oxygen and other gases such as carbon dioxide pass through the exoskeleton through tiny valves called spiracles. Insects also lack closed blood vessels (open circulatory system); instead, they have a long, thin, perforated tube (called the "dorsal aorta"), which runs through the upper part of the body and functions as the heart, pumping hemolymph to the head, thus governing the circulation of internal fluids.. The nervous system consists of a ventral nerve cord that runs the length of the body, with several ganglia and branches that reach the ends of the appendages.

An ant's head contains many sensory organs. Like most insects, they have compound eyes made up of numerous tiny lenses joined together. Their eyes are good at detecting movement, but they don't offer great resolution. They also have three small ocelli (simple eyes) on the top of their heads, which detect light level and light polarization. Compared to vertebrates, most have poor or mediocre vision, and some subterranean species are completely blind. However, other species, such as the Australian bulldog ant, have exceptional eyesight. They also have two antennae on their heads, organs with which they can detect chemical substances, air currents, and vibrations, and in turn serve to transmit and receive signals by touch. They have two strong jaws, which they use to transport food, manipulate objects, build nests, and to defend themselves. Some species have an intraoral chamber, a kind of small pocket that stores food, to later pass it on to other ants or larvae.

Its six legs are attached to the mesosoma (thorax). Hooked claws at the end of each leg, as well as pads between the claws, allow these animals to climb and cling to even surfaces as smooth as glass. Only male, queen, and reproductive ants have wings; queens lose them after the nuptial flight, leaving visible markings that are a distinctive feature of queens. However, in some species the queens and males are also wingless.

The metasoma (abdomen) of ants houses important internal organs, including those of the reproductive, respiratory (trachea), and excretory systems. The workers of many species have the ovipositor modified into a stinger which they use to subdue prey and defend their nests.

Polymorphism

In the colonies of some species there are physical castes (with workers of different classes according to size, called minor, medium and major workers), the larger ones tend to help the soldiers by being "hunters" as in the bulldog ant. They are sometimes called "soldier" ants because their more powerful jaws make them more effective in combat. In some species, medium-sized ants do not exist, and there is a large difference between smaller and larger ones. Weaver ants (genus Oecophylla), for example, have a marked bimodal distribution and other species are monomorphic, meaning all members are similar or the same in morphology and have no soldiers. Other species show continuous variation in size of the workers The smallest workers of the species Pheidologeton diversus have a dry weight 500 times less than their larger counterparts.

Workers cannot mate; however, due to the haplodiploid sex determination system of ants, workers of certain species can lay unfertilized eggs that result in fully fertile haploid males. The role of the workers can change with age and, in some species such as the so-called honey ants (genus Myrmecocystus), a certain number of young workers are fed until their gaster swells disproportionately and they serve as authentic living deposits of food. Initially it was believed that this polymorphism in the morphology and behavior of the workers was determined by environmental factors, such as nutrition or the action of hormones, which led to different types of development; however, genetic differences between worker castes have been detected in species of the genus Acromyrmex. These polymorphisms are caused by relatively small genetic changes; differences in a single Solenopsis invicta gene can determine whether the colony will have one or more queens. The Australian species Myrmecia pilosula has a single pair of chromosomes (males, in their haploid condition, they only have one chromosome); this represents the lowest known chromosome number in the animal world, making them an interesting subject of study in the genetics and developmental biology of social insects.

Development and reproduction

The life of an ant begins from an egg; if it is fertilized, a female (diploid) will be born; if not, a male (haploid). This type of reproduction, characteristic of Hymenoptera, is called haplodiploidy.

Ants are holometabolous insects, that is, they develop by complete metamorphosis, characteristic of more developed insects, in which they go through larval stages and a pupal stage before transforming into an imago. The larva remains practically immobile and is fed and cared for by the workers. The larvae are supplied with food by trophalaxis, a process by which an ant regurgitates liquid food stored in its crop. Adults also share in this way the food stored within what we can call the "social stomach." Larvae may also receive solid food, such as trophic (unfertilized) eggs, pieces of prey, seeds brought by foraging workers, or, in the case of some species, may even be transported directly to captured prey.

The larvae undergo a series of moults and reach the pupal stage. The pupa has free limbs, not attached to the body as in butterfly chrysalis. In some species the differentiation between queens and workers (both are female), and between the different castes of workers, is influenced by the diet the queens receive. larvae. Genetic influences and polyphenism by developmental environment are complex and caste determination remains the subject of research. Winged males emerge from pupae along with fertile, winged females, although some species, such as army ants They have wingless queens. Larvae and pupae have to remain at a relatively constant temperature to ensure proper development, so they are often moved from one brood chamber to another within the colony.

A new worker spends the first few days of her adult life caring for the queen and young. She is later promoted to tasks of digging and maintaining the anthill and, later, to defend the anthill and gather food. These changes can be quite sudden, and define what are called temporary castes. One possible explanation for this sequence is the numerous casualties that occur during harvesting, making it an acceptable risk only for older ants, which would likely soon die of natural causes.

Most species have a system in which only the queen and fertile females are able to mate. Contrary to popular belief, some anthills have multiple queens, while others may exist without queens. In queenless colonies, there are workers with the ability to reproduce; such workers are called gamergates, and queenless colonies are known as gamergate colonies. Most queens are the only females that are fertile.

Winged males may also mate with queens from other colonies; when introduced to a foreign colony, the male is attacked by the workers, but then releases a mating pheromone and, recognized as a friend, will be brought before the queen to mate. Males may also patrol the nest and fight against others by attacking them with its jaws, piercing their exoskeleton and then marking them with a pheromone; the marked male is then identified as an invader by worker ants and killed.

Most species of ants are univoltine, producing a new generation each year. During the mating period, which varies depending on the species, the winged males and females emerge (usually the males do so before than females) in the so-called nuptial flight. Males use visual cues to search for a common mating site where other males converge; then they secrete pheromones so that the females come. Females of some species mate with a single male, but in others they may mate with as many as ten or more different males, storing the sperm in their spermatheca. Females that have mated then search for a suitable location to start a new colony; there they tear off their wings and begin to lay eggs and take care of them. Females store sperm obtained during their nuptial flight to selectively fertilize future eggs. The first workers to be born are weak and smaller than those that are born later, but they begin to serve the colony immediately; they expand the anthill, look for food and take care of the other eggs. In most species, this is how colonies are formed. In species with multiple queens, one queen may leave the nest, along with some workers, to found a new colony elsewhere.

A great variety of reproductive strategies have been described in different species of ants. Females of some species are known to have the ability to reproduce asexually by thelithoky parthenogenesis, and one species, Mycocepurus smithii, is composed entirely of females.

Ant colonies can be long-lived. Queens can live up to thirty years, while workers live between one and three. Males, however, are more short-lived, only living a few weeks. Queen ants are estimated to live up to a hundred times longer than solitary insects of a similar size.

They remain active throughout the year in the tropics, but in colder regions they survive the winter in a state of dormancy or inactivity. The forms of inactivity are varied and some species from temperate zones have larvae that enter a state of inactivity (diapause), while others, it is only the adults that spend the winter in a state of reduced activity.

Behavior and ecology

Communication

Ants communicate with each other using pheromones. These chemical signals are more highly developed in Ants than in other Hymenoptera groups. Like other insects, ants perceive odors with their long, thin mobile antennae, which also provide information about the direction and intensity of the odors. Since most live on land, they use the soil surface to leave pheromone trails that other ants can follow. In species that forage in groups, a forager who finds food leaves a trail when he returns to the nest; the others follow this trail, and then reinforce it when they return to the colony with food. When the food source is exhausted they no longer leave the trail, and the pheromones slowly dissipate. This behavior helps them adapt to changes in their environment. For example, when an established path to a food source is blocked by an obstacle, foragers abandon it to explore new routes. If an ant is successful, it leaves a new trail during its return to mark the shortest route. The best routes are followed by more ants, reinforcing the trail and gradually finding the best path.

Ants use pheromones not only to leave trails, but also as an alarm signal in case of a threat. For example, a crushed ant releases a specific pheromone that sends those in the vicinity into a frenzy attack, and is capable of attracting more ants from other places. Some species even use "propaganda pheromones" to confuse enemy species into fighting each other. Pheromones are produced by a wide variety of structures, including Dufour's gland, venom glands and hindgut glands, pygidium, the rectum, the sternum and the hind tibia. Pheromones can also be exchanged when mixed with food and are transferred by trophalaxis, an action that allows information to be transmitted within the colony. This also allows them to determine which group of work (for example, collecting or maintaining the anthill) belongs to the other members of the colony. In species with castes of queens, the workers begin to raise new queens in the colony when the dominant queen stops producing a specific pheromone.

Some ants produce sounds by stridulation (rubbing two parts of the body together), using the gaster segments and mandibles. The sounds can be used to communicate with members of the colony or with other species.

Defense

Ants attack and defend themselves by biting and, in many species, by stinging (only a few species have actual stingers), often by injecting or spraying chemicals such as formic acid. Native to Central and South America, Paraponera clavata is considered to have the most painful sting of any insect, although it is generally not fatal to humans, and receives the highest score in the < i>Schmidt Sting Pain Index. The sting of the species Myrmecia pilosula can be lethal, but an antiserum has been developed. Ants of the genus Solenopsis are unique in having a venom sac containing piperidine alkaloids. Their bites are painful and can be dangerous to hypersensitive individuals.

Ants of the genus Odontomachus are equipped with jaws called "trap-jaws", which close faster than any other predatory appendage in the animal kingdom. A study on the species Odontomachus bauri recorded speeds of between 126 and 230 km/h, with jaws closing in 130 microseconds on average. It was also found that these ants used their jaws as a catapult to expel intruders or to launch themselves backwards to avoid a threat. Before striking, the ant opens its jaws wide and they are locked in that position by an internal mechanism.. The energy is stored in a thick group of muscles and is released explosively by the stimulation of sensory hairs inside. The jaws also allow for slow, precise movements when performing other tasks such as caring for larvae. Trap-jaws are also found in the genera Anochetus, Orectognathus, and Strumigenys, as well as in some members of the tribe Dacetini, in what is an example of convergent evolution.

A species of Malayan ant of the superspecies Camponotus cylindricus has enlarged mandibular glands that extend into its gaster. When disturbed, the workers rupture the gaster membrane, causing a burst of secretions containing acetophenones and other chemicals that immobilize small attacking insects. Because of this action, the worker dies. Suicidal defense of workers has also been recorded in the Brazilian ant Forelius pusillus where a small group of ants leave the safety of the nest after sealing the outside entrance. every afternoon.

In addition to fending off predators, they have to protect their colonies from pathogens. Some worker ants are in charge of the hygiene of the colony, and their activities include removing the corpses of dead companions (necrophoresis). In the species Atta mexicana, oleic acid has been identified as the compound released by dead ants that causes this necrophoric behavior, while Linepithema humile workers react to the absence of characteristic chemical compounds (dolichodial and iridomyrmecin) present on the cuticle of their living nest mates. In ants, different castes have different response thresholds to particular odors, which could be due to a different number and distribution of odor-receptor neurons in the antennae. Sensitivity to oleic acid released from carcasses is caste-specific: Mexican Atta soldiers are not sensitive to kill signals, i.e. oleic acid, but do respond to alarm pheromones.

The elaborate architecture of the anthill protects them from natural threats such as flooding and overheating. A very curious case is that of the workers of Cataulacus muticus, an arboreal species that lives in trunk holes, which fight flooding by drinking water inside the nest and expelling it outside. The small Camponotus anderseni, which builds its nests in mangrove tree cavities, has adapted to a remarkable way to tidal flooding; they block the entrance to the nest with the head of a soldier and prevent the entry of water, and in the absence of fresh air and the increase of CO2 in the nest, they can survive underwater by switching to anaerobic respiration.

Learning

Many animals can learn behaviors by imitation, but ants may be the only group other than mammals where interactive learning has been observed. An experienced forager of Temnothorax albipennis leads an inexperienced companion to a newly discovered food source through the extremely slow process of so-called "tandem recruitment". The "student" ant gains knowledge from her "tutor." Both the tutor and student recognize how their partner's progress is progressing, causing the tutor to slow down when the student falls behind, and speed up when the student gets too close.

Controlled experiments with colonies of Cerapachys biroi suggest that individuals can choose their role in the anthill based on their previous experience. An entire generation of identical workers was divided into two groups in which success in foraging was controlled. One group was continually rewarded with prey, while the other was always made to fail. As a result, the successful group members intensified their foraging activity while the unsuccessful group left the nest less and less. A month later, the successful collectors were continuing their role, while the rest had switched to specializing in brood care.

Colony Building

Many species build complex anthills, but others are nomadic and do not create permanent structures. They can build colonies underground or build them in trees and other natural or man-made structures. These nests can be found underground, under rocks or logs, inside logs, hollow stems, or even acorns. The materials they use to build the nest generally include soil and plant matter. They choose carefully where to build the colony; Temnothorax albipennis avoid places with dead ants, as this may indicate the presence of parasites or disease. At the first sign of a threat, they quickly abandon established colonies.

The legionary ants of South America and the traveling ants of Africa (genus Dorylus) do not build permanent anthills, but alternate nomadism with stages in which the workers form a temporary nest. The workers use their own bodies to hold on to each other, thus creating the nest structure to protect the queen and larvae, and later dismantle it when they continue on their journey.

Weaver ant workers build nests in trees by attaching leaves together; first they hold them by means of "bridges" of workers and then cause the larvae to produce silk while moving them along the edges of the leaves. Similar construction methods have been observed in some Polyrhachis species.

Food

Most ants are direct or indirect generalist predators, scavengers, or herbivores, but some species have evolved toward specializing in ways of obtaining food.

Leaf-cutter ants (Atta and Acromyrmex) feed exclusively on a fungus that only grows within their colonies. They continually collect leaves which they then take back to the colony, cut into small pieces and put in fungal gardens. The workers specialize in tasks according to their size; the largest ones cut stems, the medium ones chew the leaves and the smallest ones take care of the fungi. These ants are sensitive enough to recognize the fungal reaction to different types of vegetables, apparently by detecting chemical signals from the fungus. If a certain type of leaf is toxic to the fungus, the colony will not pick any more. The ants feed on structures produced by the fungi called gongylidia. Symbiotic bacteria on the outer surface of the ants produce antibiotics that kill bacteria that could harm the fungus.

In the species Leptanilla swani (subfamily Leptanillinae) the larva feeds its own hemolymph to the queen through specialized glands located in its prothorax and the third abdominal segment. This behavior is similar to that of < i>Adetomyrma venatrix (not related to the above), a rare and primitive species endemic to Madagascar, known as the vampire ant or Dracula ant, because instead of the larvae regurgitating food as is usual in the In most species, workers and queens bite and pierce the skin of larvae to feed on their body fluids. This surprising way of feeding does not cause the death of the larva, which is why it is called "non-destructive cannibalism".

Dream

In a US study conducted jointly by the University of South Florida and the University of Texas at Arlington, sleep patterns were investigated in fire ants. Because this species typically lives underground, the researchers hoped that its sleep patterns would not be influenced by the sun.

According to the study, the queens of fire ants sleep on average 90 times a day for about 6 minutes each time, which is equivalent to about 9 hours of sleep a day, while the workers of the species have about 250 naps of about a minute (about 4 hours and 50 minutes a day); they do this so that 80% of the workers are awake at any one time to protect and serve the colony. The research team also concluded that there was evidence to suggest that queen ants dream when they are in deep sleep.

This resting division may help explain why fire ant queens live for six years (in some species as long as 45 years), while fire ant workers normally live for six months..

Orientation

Harvester ants travel distances of up to 200 meters from their nest, and find their way back, even in the dark, thanks to the scent trails they leave behind. In hot, arid regions, ants that come out during the day are in danger of dying from drying out, so the ability to find their way back more quickly reduces this risk. Thus, diurnal ants from desert areas of the genus Cataglyphis, such as Cataglyphis bicolor, which inhabits the Sahara desert, orient themselves by remembering the direction and distance they have covered. To measure the distance traveled, they use a kind of internal pedometer that keeps track of the steps taken, and also evaluates the movement of objects in their visual field, and for the direction they take the position of the Sun as a reference; they integrate this information to find the shortest possible return route to the nest. Like all ants, they also make use of visual cues when available, and use other tactile and olfactory cues to orient themselves. Some species are capable of using the Earth's magnetic field for orientation. Their compound eyes have specialized cells that detect polarized light from the Sun, which they use to determine direction; these polarization detectors are sensitive to the ultraviolet region of the light spectrum. In some ant species soldier, a group of foragers that breaks away from the main column can rotate until the first ant in the line joins the last and form a circle; in this way the workers continue to spin indefinitely until they die of exhaustion.

Locomotion

The workers do not have wings and the fertile females lose them after the nuptial flight to found their own colony. Therefore, unlike their vespid ancestors, most ants get around on foot. Some species are capable of jumping; for example, Harpegnathos saltator is capable of jumping by synchronizing the action of its pairs of hind and middle legs. There are also other species, such as Cephalotes atratus, called ants "gliders" (this is usually a common trait in most tree ants). Ants with this ability are able to control the direction of their descent as they fall.

Some species can form chains to pass over bodies of water, slip underground, or through gaps in vegetation. Others even go so far as to create floating rafts that allow them to survive floods. These rafts may play an important role in allowing ants to colonize islands. Polyrhachis sokolova, a species of ant found in Australian mangroves, can swim and live in underwater colonies. Since they do not have gills, these ants breathe thanks to air pockets trapped in submerged anthills.

Cooperation and competition

Not all formicids form the same type of society. Bulldog ants or Australian giant ants (genus Myrmecia) are some of the largest and most basal (primitive) ants. Like virtually all ants, they are eusocial, but their social behavior is underdeveloped compared to other species. Each individual hunts alone, using its large eyes instead of its chemical senses to find its prey.

Some species (such as Tetramorium caespitum) attack and capture neighboring ant colonies. Others are less expansionist, but just as aggressive; they invade colonies to steal eggs or larvae, which they then eat or raise as slave workers. Among those that carry out raids, there are some very specialized ones, such as Amazon ants (Polyergus), which are unable to feed themselves and need captured workers to survive. The enslaved species Temnothorax have developed an opposite strategy, and manage to destroy up to two thirds of the female pupae of the slave species Protomognathus americanus, although they spare the males (which they do not participate in raiding raids as adults).

Ants identify their colony mates by their odor, which comes from the hydrocarbon secretions that coat their exoskeleton. If an ant is separated from its original colony, it ends up losing the scent of its colony. Any ant that enters an anthill without having a matching scent will be attacked.

Some parasitic species enter host ant colonies and establish themselves as social parasites; Species such as Strumigenys xenos are totally dependent and have no workers, instead feeding on food collected by their hosts Strumigenys perplexa. This form of parasitism can be observed in many genera of formicids, but the parasitic ant is usually a closely related species to its host. Parasites use a variety of methods to enter the host's nest. A parasitic queen can enter the host nest before the first larvae hatch, thus becoming established before colony scent develops. Other species use pheromones to confuse or trick hosts into bringing the parasitic queen into the nest. Some simply force their way in.

A conflict between the sexes of the same species can be observed in some species of ants in which the fertile individuals apparently fight to produce offspring that are as closely related to them as possible. The most extreme form involves the production of cloned offspring. The extreme of sexual conflict is observed in Wasmannia auropunctata, where queens produce only diploid clonal daughters by thelithoky parthenogenesis, and only males, also clonal, are produced by a process in which males are produced. Males remove the maternal contribution from the diploid egg, resulting in offspring with a nuclear genome identical to that of the parent male.

Hygiene

In a paper by Tomer J. Czaczkes, a biologist at the University of Regensburg, black garden ants (Lasius niger) were found to build latrines in their anthills. It is not clear why, but it is believed that it may be due to the newly hatched ants going to the toilet and taking a kind of bath to quickly acquire the smell of the colony.

Relationship with other organisms

Ants have symbiotic relationships with a wide variety of species, including other ants, insects, plants, and fungi. They are the prey of many animals and even some fungi. Some species of arthropods spend part of their lives in anthills, either feeding on the ants, their larvae, their eggs, and their food reserves, or hiding from predators. These occupants can closely resemble ants in appearance. The nature of this ant mimicry (termed "myrmecomorphy") varies, and in some cases includes Batesian mimicry, in which mimicry reduces the risk of predation. Others show Wasmanian mimicry, a type of mimicry seen only in tenants.

Aphids and other insects secrete a sweet liquid called honeydew when they feed on sap. The sugars in honeydew are a high-energy food source, foraged by many species of formicids. In some cases, aphids secrete honeydew in response to being tapped with their antennae. The ants, in turn, keep their predators at bay and move the aphids from one feeding area to another. When migrating to a new area, many colonies take the aphids with them to ensure a continuous supply of honeydew. Ants also keep mealybugs to collect their honeydew. These mealybugs can become a serious pest of pineapples if there are ants willing to protect them from their natural enemies.

Myrmecophilous caterpillars of the family Lycaenidae are herded by ants, which take them to feed during the day and protect them inside the anthill at night. Caterpillars have a gland that secretes honeydew when they are massaged. Some caterpillars emit vibrations and sounds that are perceived by the ants. Other caterpillars have gone from myrmecophilous to myrmecophagous: they emit a pheromone that makes the ants act as if the caterpillar were one of their own larvae, so the ants carry it to the nest., where the caterpillar devours its larvae.

Mushroom-growing ants (tribe Attini) cultivate certain species of fungi of the genera Leucoagaricus or Leucocoprinus of the family Agaricaceae. In this mutualism between ants and fungi, each species depends on the other to survive. The ant Allomerus decemarticulatus has developed a three-way association with the plant host Hirtella physophora (Chrysobalanaceae) and a sticky fungus that serves to trap their insect prey.

Army ants (popularly known as "marabunta") are nomadic and famous for their raids or "raids", in which huge numbers of foragers simultaneously invade certain areas attacking their prey en masse. "Armies" of no fewer than 1,500,000 of these ants destroy nearly all animal life in their path. Dorylus spp., known locally as Siafu, attack everything in their path, including humans.

The ants Myrmelachista schumanni create the so-called “devil's gardens” by killing the surrounding plants by injecting them with formic acid, leaving only the trees where they make their nests (Duroia hirsuta). This allows the trees to multiply and provides more places for ants to nest in the trunks of Duroia. Although some ants obtain nectar from the flowers, pollination by these insects is rare. Some plants have special extrafloral nectar-exuding structures that provide food for ants, which in turn protect the plant from herbivorous insects. Central American species such as the ergot (Acacia cornigera) have hollow spines that harbor colonies of biting ants (Pseudomyrmex ferruginea) that defend the tree from insects, browsing mammals and epiphytic vines. Studies based on isotopic labeling suggest that plants also obtain nitrogen from symbiotic ants. In return, the ants obtain food from small globules (Belt bodies) rich in lipids and proteins. Another example of this type of ectosymbiosis is that of the trees of the genus Macaranga, which have stems adapted to house colonies of Crematogaster ants.

Many tropical tree species have seeds that are dispersed by ants. Seed dispersal by ants (called myrmecochory) is widespread and recent studies estimate that nearly 9% of all plant species have this type of association with ants. Some plants in fire-prone grasslands are especially dependent on ants for survival and spread, as they transport their seeds safely underground. Many of the seeds dispersed by ants have special external structures, eleosomes, which are used as food by ants. Convergence, possibly a form of mimicry, can be observed in stick insect eggs. These eggs have an edible structure similar to the eleosoma, so the ants take them to the anthills (which helps their dispersal and protection), where they hatch and leave the nest.

Most ants are predatory, feeding on and obtaining food from various social insects, including other ants. Some species specialize in feeding on termites (Megaponera and Termitopone) while other species, such as those in the subfamily Cerapachyinae, feed on other ants. Some termites, such as Nasutitermes corniger, form associations with certain ant species to keep other predatory ant species away. The tropical wasp Mischocyttarus drewseni covers the entrance to its nest with a repellent chemical ants. Many tropical wasps are believed to build their nests in trees and cover them to protect themselves from ants. Stingless bees (Trigona and Melipona) use chemical defenses against ants.

Old World flies of the genus Bengalia (family Calliphorids) are ant predators and kleptoparasites, stealing prey or young from the jaws of adult ants. Females without The wings and legs of the Malayan humpback fly Vestigipoda myrmolarvoidea live in the nests of ants of the genus Aenictus, and are cared for by them.

Fungi of the genera Cordyceps and Ophiocordyceps infect ants, causing them to climb up plants and sink their mandibles into plant tissue. The fungus kills the ant, grows on its corpse, and produces a fruiting body. The fungus appears to alter the behavior of the ants to facilitate the dispersal of their spores in a suitable microhabitat for the fungus. Strepsipteran parasites also manipulate their behavior by making them climb up grass stalks, helping the parasite find a mate. A nematode (Myrmeconema neotropicum) that infects ants of the species Cephalotes atratus causes the black gasters of the workers to turn red, and modifies the behavior of the ant causing it to carry very high Birds confuse these conspicuous red gasters with ripe fruits, such as that of the weeping red, and eat them. Bird droppings are collected by other ants, which carry the young as food, contributing to the spread of the nematode.

South American poison dart frogs of the genus Dendrobates feed primarily on ants, and the toxins they secrete through their skin may originate from these insects. Some antbirds and nuthatches follow ants warriors such as Eciton burchellii to feed on insects that are exposed by their massive incursions; for a time this behavior was considered mutualistic, but more recent studies show that it is actually kleptoparasitism, since the birds steal the prey and the ants not only do not benefit, but are harmed. Some birds have a peculiar behavior called "ant bathing" (anting in English). They perch on anthills, or take them to put on their wings and feathers; it is possible that they do it to eliminate ectoparasites, but it is a behavior about which not much is known yet.

Anteaters, pangolins, and several Australian marsupial species have special adaptations for living on a diet of ants. These adaptations include long, sticky tongues for catching them and strong claws for tearing through anthills. Brown bears (Ursus arctos) have been shown to feed on ants, with approximately 12%, 16%, and 4% of their fecal volume in spring, summer, and fall, respectively, is made up of ants.

Relationship with humans

Ants play multiple ecological roles that are beneficial to humans, such as removing pests and aerating soil. The use of weaver ants in citrus cultivation in southern China is considered to be one of the oldest known applications of biological control. On the other hand, ants can become a problem when they invade buildings, or cause economic losses in agricultural activities.

In some parts of the world (mainly Africa and South America), large ants, especially army ants, are used as sutures. To do this, they press the edges of the wound against each other while applying the ants; they bite down hard with their jaws and at that moment the body is severed, leaving only the head and jaw to keep the wound closed.

Some species of the Ponerinae family have a highly toxic and potentially dangerous venom that may require medical attention. These species include Paraponera clavata (bullet ant or tocandira) and Dinoponera spp. (false tocandira) from South America, as well as Myrmecia from Australia.

In South Africa they are used to help harvest rooibos (Aspalathus linearis), shrubs that have small seeds used to make herbal infusions. The plant disperses its seeds widely, making manual collection difficult. The ants collect these and other seeds and store them in the anthill, from where humans can collect them all together. Up to 200 grams of seeds can be obtained from each anthill.

Although most species survive attempts by humans to eradicate them, a few are threatened. They are mostly island species that have developed specialized characteristics, such as the endangered Aneuretus simoni from Sri Lanka and Adetomyrma venatrix from Madagascar.

I eat food

Ants and their larvae are eaten in different parts of the world. The eggs of two species are the basis of the Mexican dish known as escamoles. They are considered a form of insect "caviar" and can fetch as much as $90/kg, being seasonal and hard to find. In the Colombian department of Santander, culona ants (Atta laevigata) are eaten after being roasted alive.

In parts of India and much of Burma and Thailand, a paste made from a species of weaver ant (Oecophylla smaragdina) is served as a condiment with curry. The eggs and larvae of this ant, as well as the ants themselves, are used in a Thai salad, yum (ยำ), in a dish called yum khai mod daeng (ยำไข่มดแดง) or red ant egg salad, a dish originating in Northeast Thailand. Saville-Kent, in his work Naturalist in Australia, wrote “Beauty, in the case of the weaver ant, is more than skin deep. Its attractive, almost candy-like transparency was possibly what prompted the first attempts to consume it by humans." Crushed in water, much like lemonade, "these ants produce a pleasant sour drink that is highly prized by the natives of North Queensland, and even by many European palates."

In his work First Summer in the Sierra, John Muir comments that the California Paiute ate the acid gasters of carpenter ants. Mexican Indians eat the teeming workers, or living honey stores, of the honey ant (Myrmecocystus mexicanus).

Like the Plague

Some species of ants are considered pests, and due to the adaptive nature of their colonies, eliminating them entirely is nearly impossible. Therefore, pest management focuses on controlling local populations, rather than trying to eliminate an entire colony, and most attempts at control are temporary solutions.

Among the species considered pests are Anoplolepis gracilipes, Camponotus consobrinus, Linepithema humile, Monomorium pharaonis, Myrmica rubra, Solenopsis invicta, Tapinoma sessile. Tetramorium caespitum, and the genus Camponotus. Populations are controlled by means of insecticide baits, in granulated or liquid form. The ants collect the bait as if it were food and carry it to the anthill, where the insecticide is inadvertently transmitted to other members of the colony by trophallaxis. Boric acid and borax are two common insecticides, being relatively safe for humans. Bait can be spread over a wide area to control species such as Solenopsis invicta, which occupy large areas. Colonies of this species can be destroyed if they are followed to the nest and boiling water is poured into the nest to kill the queen. This works in about 60% of cases and requires about fourteen liters of water per nest.

In the field of agricultural production, ant control is carried out mainly through three methods:

- the application of any insecticide in total coverage;

- the placement of "barrels" in the trunk, if it is control in farms that have arboreal species as the object of cultivation (e.g., in fruit farming); and

- the use of toxic baits.

The application in full coverage has low residuality and is not enough to eliminate the subterranean colonies. The use of "barriers" is difficult. It consists of the application of sticky bands of polybutane, or insecticides, to the physical barriers or to the trunk. Sticky barriers lose effectiveness over time due to dust or debris that settles on them. The most efficient barriers are plastic bands with slow-release chlorpyrifos, whose efficacy exceeds 200 days.

The use of toxic baits is efficient and inexpensive, with variable results depending on the bait in question. Some foraging ants do not accept citrus pulp and oat bran covered with brown sugar. On the other hand, the ground balanced food for dogs, and the ground of dead insects without added sugar, had a high acceptance. By adding fipronil and 1% phenoxycarb, the baits maintained their attraction and controlled ants, which ingest insecticide particles from the bait as they transported it to the colony. It is common for worker ants to exchange various substances with each other (trophallaxis) and, based on this habit, the first ones to come into contact with the insecticide contaminate others. Consequently, an insecticide will be suitable for this type of formulation when it does not kill quickly, when it is delayed acting and when it is effective at low concentrations. The death of the gardener ants causes a general disorganization of the fungus that serves as their food, enabling the growth of contaminants that lead to the death of the anthill. The bait made of citrus flour and 2% fipronil, applied in the mouth of the anthills, is also well accepted and performs good control.

Like invasive species

Among the hundred worst invasive organisms included in the Global Database of Invasive Species, compiled by the IUCN/SSC Invasive Species Specialist Group (ISSG), are five ants: Anoplolepis gracilipes, < i>Linepithema humile, Pheidole megacephala, Solenopsis invicta and Wasmannia auropunctata. Invasive ants have a major impact on ecosystems by affect their composition and their ecological interactions. For example, they vary the composition of native ants and affect their important roles as predators, scavengers, herbivores, detritus eaters, and granivores, as well as their function as a food source for a variety of specialized ant species. They also alter specialized interactions with plants in seed dispersal, pollination, protection of myrmecophilous plants, and with animals such as honeydew-producing Hemipterans. Island ecosystems are especially sensitive to invasive ants, particularly on oceanic islands where there are few ant species and the invaders find no competitors or predators. Many native invertebrates may decline or even become extinct there, lacking defensive adaptations against exotic ants.

As biological pest control

Its use by man in the biological control of pests is very old. In Yemen, ants were managed to decrease populations of date palm pests. In China since the Middle Ages, farmers have regulated citrus pests with the weaver ant Oecophylla smaragdina, and have controlled some borer lepidoptera in sugarcane plantations introducing colonies of Tetramorium guineense.

Some exotic ants, despite being classified as invasive, are used in some regions as biological pest controllers, for example, Pheidole megacephala in the control of sweet potato tetouan in Cuba, Wasmannia auropunctata in the control of cocoa pests in Gabon and Cameroon, or to repel various herbivorous arthropods with Solenopsis invicta or with Linepithema humile in the United States.

In science and technology

Myrmecologists study them in the laboratory and in their natural environment; their variable and complex social structures make these insects ideal model organisms. Ultraviolet vision in ants was discovered by Sir John Lubbock in 1881. The study of formicids has tested hypotheses in ecology and sociobiology and has been especially important in examining the claims of kin selection theories and strategies. evolutionarily stable. Their colonies can be studied by raising them or keeping them temporarily in artificial anthills, glass structures specially made for this use. Specimens can be marked with different colors for their study and monitoring.

The successful techniques used by the colonies have been studied in computer science and robotics to produce distributed, fault-tolerant systems for solving problems. This field of biomimicry has led to studies of their locomotion, with the result of search engines based on their "search for traces", fault-tolerant storage computer systems and network algorithms.

As with other animals, studies have been carried out on these insects for their application in military tactics such as swarming ('swarm'). Thus, after a series of simulation-based experiments conducted in a study of how ants deposit pheromones to coordinate their foraging and other activities, the US Department of Defense discovered that pheromone-based algorithms achieved impressive results on the control of a group of unmanned aerial vehicles in an attack on critical moving targets. Other studies on animal military strategy showed that ants differ from bees and other social insects by the use of swarming not only in the search for food or in defense of the colony, but also in territorial expansion wars against other ants. These wars are often protracted, and of an operational complexity that makes them remarkably human-like.

In culture

Ants often appear in children's fables and stories, representing hard work and cooperative effort. They are also mentioned in religious texts, such as in the Bible's Book of Proverbs, where they are used as a good example to humans for their hard work, or in the Qur'an, where an ant is said to warn others not to. return home to avoid being accidentally crushed by Solomon and his marching army. In the fable attributed to Aesop, The Grasshopper and the Ant, they are used as an example of perseverance and hard work, but in the end it has a reward.

In some parts of Africa they are considered messengers of the gods. The sting of some ant species is often said to have healing properties. It is claimed that the bite of some species of Pseudomyrmex relieves fever. In the mythology of some Amerindian peoples, such as the Hopi, they are considered the first animals. Other groups use its sting as a test of resistance in initiation rites.

The societies formed by ants have always fascinated humans, and have been written about both humorously and seriously. Mark Twain wrote about these insects in his work A Tramp Abroad (1880). Some contemporary authors have used them as an example to address the issue of the relationship between society and the individual, such as Robert Frost in his poem Departmental and T. H. White in his fantasy novel The Once and Future King; In The Life of Ants, Maurice Maeterlinck, Nobel Prize for Literature, considers that these insects are full of mysteries, but that, at the same time, they can awaken endless analogies with human behavior. The father of ethology and winner of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine Karl von Frisch in his novel Twelve little guests, through various insects, among which are ants, reflects on tiny beings through those of us who barely pay attention, except when they bite us, run around our house or devour our food. The plot of the science fiction trilogy by French entomologist and writer Bernard Werber, Ants, is divided between the world of ants and that of humans; ants and their behavior are described using current scientific knowledge about them.

In recent times, cartoon characters have been created such as The Atomic Ant and blockbuster 3D animated films with these insects as protagonists such as Antz, Bugs: A Miniature Adventure or The Ant Bully. There is also a superhero from the 1960s from Marvel Comics called Ant-Man, about which a film of the same title was released in 2015, directed by Edgar Wright, and a sequel in 2018, directed by Peyton Reed.. Renowned myrmecologist E. O. Wilson wrote a short story, Trailhead, for The New Yorker magazine in 2010, describing the life and death of a queen ant and the rise and fall of their colony, from the point of view of some ants.

Between the late 1950s and late 1970s, ant farms were popular educational toys in the United States. Later versions use clear gel instead of soil, allowing for greater visibility. In the early 1990s the video game SimAnt, which simulated an ant colony, won the 1992 CODiE Award for "Best Simulation Program"..

They are also the inspiration for many science fiction creatures, such as the Formics from Ender's Game, the insects from Space troops or the giant ants from the movie Them!. In strategy games, ant-inspired species often benefit from a higher production rate thanks to their hard-working mentality, as is the case with the klackons in the Master of Game series. Orion or the ChCh-t from Deadlock II. All of these characters tend to have a "group mind", a common misconception about ant colonies.

Additional bibliography

- Huber, Pierre (1867). History of ants. Translated by M. Fernández Llamazares. Imp. and Libr. de Gaspar and Roig, Eds.

- López-Riquelme, G. O.; Ramon, F. (2010). "The happy world of ants." TIP: journal specializing in chemical-biological sciences 13 (1): 35-48. ISSN 1405-888X.

- López-Riquelme, Germán Octavio (2008). Ants as model systems for complex behavior. Neurobiological bases of chemical communication and division of labour in ants (Ph.D.). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.3145.1689.

- Markle, Sandra (2007). Legionary ants. Animals Cartoons. Lerner Editions. ISBN 0822577305.

- Tanquary, Maurice Cole (2009). BiblioBazaar, LLC, ed. Biological and Embryological Studies on Formicidae (in English). ISBN 0559981015.

Contenido relacionado

Atacama Desert

Opégrapha

Dinochloa