Flemish

The flamenco is a Spanish musical genre that developed in Andalusia, especially in the areas of Cádiz and its ports, San Fernando, Jerez de la Frontera, Seville and the towns of its province such as Lebrija and Utrera, Huelva, Granada and Córdoba as well as in some areas of the Region of Murcia, Castilla la Mancha and Extremadura. Its main facets are singing, playing, and dancing, also having its own traditions and rules. As we know it today, flamenco dates from the 18th century, and there is controversy about its origin, since although there are different opinions and aspects, none of them has been historically proven. Although the RAE dictionary associates it with Andalusian popular culture and the notable presence of the gypsy people in that, the fusion of the different cultures that coincided in Andalusia at the time is more than perceptible. Although it is true that the gypsies arrived in Spain in the s. XV and despite vital restrictions and antigypsyism they managed to settle in Andalusia around the s. XVI-XVII, when flamenco began. Surely the cultural baggage that the gypsy people brought along from their pilgrimage to India converged with the native Andalusian sounds, giving rise to flamenco.

Of all the hypotheses about its origin, the most widespread thesis is the one that exposes the diverse origin from the Castilian sung ballads to the music of the Moors or the Sephardic. The cultural miscegenation that occurred in Andalusia at that time (natives, Muslims, Castilians) led to its creation. In fact, its germ already existed in the region of Andalusia long before the gypsies arrived, also taking into account that there were gypsies in other regions of Spain and Europe, but flamenco was only cultivated by those who were in Andalusia.

In November 2010, Unesco declared it Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity at the initiative of the autonomous communities of Andalusia, Extremadura and Murcia. It is also Andalusian Ethnological Intangible Cultural Heritage and is registered in the General Inventory of Movable Property of the Region of Murcia established by the General Directorate of Fine Arts and Cultural Property.

Its popularity in Latin America has been such that in Argentina, Costa Rica, Cuba, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico, Panama, Puerto Rico and Venezuela, various groups and academies have emerged. Its wide dissemination and study in Chile it has even allowed the appearance of well-known national figures, such as guitarists Carlos Ledermann and Carlos Pacheco Torres, who teaches Flamenco Guitar at the Rafael Orozco Superior Conservatory of Music in Córdoba. In Japan it is so popular that it is He says that there are more flamenco academies in that country than in Spain.

Etymology

The word flamenco, referring to the artistic genre known by that name, dates back to the mid-19th century. There is no certainty of its etymology, so several hypotheses have been raised:

- Because Gypsies are also known as Flemish: in 1881 Demofilo, in the first study on flamenco, argued that this genre should its name to the fact that its main growers, gypsies, were frequently known in Andalusia under that denomination. In 1841 George Borrow in his book Los Zíncali: The Gypsies of Spain He had already collected this popular denomination, which reinforces Demofilo's argument.

Gypsies or Egyptians is the name given in Spain both in the past and in the present to which we call in English gypsies, although they are also known as "new bottles", "germanos" and "flamencos"; [...] The name "flamencos", with which to present are known in different parts of Spain,[... ]

It is not certain why gypsies were called "flamenco", however, there are numerous reports that point to a slang origin, placing the term "flamenco" within the lexicon of the germanía. This theory holds that "flamenco" it derivates from flamancy, a word that comes from "flame" and that in germanía it refers to the fiery temperament of the gypsies. In the same sense, the dictionary of the Royal Spanish Academy says that "flamenco" colloquially means "cool or insolent", an example of which is the phrase "ponarse flamenco". In a similar meaning, the term "flamenco" is used as a synonym for "knife" and of "brawl" or "algazara" by Juan Ignacio González del Castillo, in his farce The braggart soldier (ca. 1785). However, Serafín Estébanez Calderón, who in his Escenas andaluzas (1847) provided the first descriptions of flamenco situations, did not use that name to describe them.

- By parallel with the ditch bird of the same name: some hypotheses relate the origin of the name of the flamenco genre to the birds of the same name. One of them says that flamenco receives that denomination because the appearance and body language of its interpreters remind them of such birds. Marius Schneider, instead, defends that the origin of the term may be in the name of these birds, but not in their likeness with the style of the dancers but in that the mode of me, which is the predominant in the flamenco repertoire, is related in medieval symbolology, among other animals, with flamenco.

- Because its origin is in Flandersanother number of hypotheses link the origin of the term with Flanders. According to Felipe Pedrell, flamenco arrived in Spain from those lands in the time of Carlos V, hence his name. Some add that in the dances that were organized to welcome the monarch he boasted with the scream of Dance to flamenco! However, the term "flamenco" linked to music and dance arose in the mid-19th century, several centuries after that fact.

- For being the music of the "fellah min gueir ard", the landless Moorish peasants: according to the notary and political Blas Infante, the term "flamenco" comes from the Andalusian expression fellah min gueir ard (فلاح من زير أرض), which means "landless peasant". According to him, many Moors were integrated into the Gypsy communities, with which they shared their ethnic minority outside the dominant culture. Infante assumes that in that breeding ground the flamenco song should emerge, as a manifestation of the pain that the people felt for the annihilation of their culture. However, Blas Infante does not provide any historical source of documentary evidence that aligns this hypothesis and, taking into account the fierce defense that he made throughout his life of an agrarian reform in Andalusia, that pales the mere situation of the Andalusian laborer of his time, this interpretation seems more ideological and political than historical or musicological. However, Father García Barriuso also considers that the origin of the Flemish word could be in the Arabic expression used in Morocco. fellah-manguwhich means "the songs of the peasants". Luis Antonio de Vega also provides the expressions felahikum and felah-enkumThey have the same meaning.

Cante jondo

According to the dictionary of the RAE, the "cante jondo" is "the most genuine Andalusian cante, with deep sentiment". This dictionary includes the phrases "cante jondo" or "cante hondo", which confirms that the term "jondo" It is nothing more than the Andalusian dialectal form of the word "hondo", with its characteristic aspiration of the h coming from the initial f. However, Máximo José Kahn came to maintain that the term "jondo" comes from the Hebrew locution "jom-tob" or "yom-tob", an ending of some synagogal songs. According to García Matos and Hipólito Rossy, not all flamenco cante is cante jondo. Manuel de Falla considered cante jondo to be ancient cante, while flamenco cante was modern.

Distinction between flamenco and Andalusian folklore

The flamenco style took shape during the 19th century, on the basis of the traditional music and dance of Andalusia, whose origins are ancient and diverse. However, flamenco is not the folklore of Andalusia (made up of seguiriyas, sevillanas, fandangos, verdiales, trovos, the chacarrá, the vito...), but an artistic genre that is fundamentally scenic.

At no time in its history has flamenco gone from being a music performed by minorities, with greater or lesser diffusion. The emergence of professional singers and the transformation of popular songs by gypsies made their style move away considerably from traditional tunes.

Even so, flamenco is considered a first-rate tourist attraction for Andalusia, both as a show and as an art to be studied, even as a doctorate, university expert or subject for a university diploma. Prizes are also awarded for the research in flamenco.

History

It is believed that the flamenco genre arose at the end of the 18th century in cities and agricultural towns of Lower Andalusia, highlighting Jerez de la Frontera as the first written vestige of this art, although there are practically no data regarding those dates and the manifestations from this period are more typical of the bolero school than of flamenco. There are hypotheses that point to the influence on flamenco of types of dance from the Indian subcontinent —place of origin of the gypsy people— as is the case of the kathak dance. The documentary Gurumbé, songs from your black memory, shows the African influence in the rhythms and choreography of flamenco.

Casticism

In 1783 Carlos III promulgated a pragmatic that regulated the social situation of the gypsies. This was a momentous event in the history of Spanish gypsies who, after centuries of marginalization and persecution, saw their legal situation improve substantially.

After the Spanish War of Independence (1808-1812), a feeling of racial pride developed in the Spanish conscience, which contrasted the French-style enlightened man with the telluric force of the majo, the archetype of individualism, grace and traditionalism. In this environment, the cañí fashion triumphed, since traditionalism sees in the gypsy an ideal model of that individualism. The emergence of the bullfighting schools in Ronda and Seville, the rise of banditry and the fascination for everything Andalusian manifested by European romantic travelers, were shaping Andalusian costumbrismo, which triumphed in the Madrid court.

At this time there is evidence of disagreements over the introduction of innovations in art.

The singing cafés

Singing cafés were nightclubs where spectators could drink drinks while enjoying musical performances. In them, all kinds of excesses frequently took place, which is why the majority of the population lived with their backs to them.[citation required]

According to the cantaor Fernando el de Triana published in his memoirs, in 1842 there was already a café cantante in Seville, which was reopened in 1847 under the name Los Lombardos, like Verdi's opera. However, at that time the different songs and interpreters were quite disconnected from each other. In 1881 Silverio Franconetti, a singer with an extensive repertoire and great artistic gifts, opened the first flamenco café cantante in Seville. In Silverio's café, the cantaores were in a very competitive environment, as Silverio himself liked to challenge the best cantaores who passed through his café in public.

The fashion for cafés cantantes allowed the emergence of the professional singer and served as a melting pot where flamenco art was configured. In them, non-gypsies learned the songs of the gypsies, while the latter reinterpreted Andalusian folk songs in their own style, expanding the repertoire. Likewise, the taste of the public contributed to shaping the flamenco genre, unifying its technique and its theme.

The anti-flamenco movement of the generation of '98

Flamenco, defined by the Royal Spanish Academy as the "love for flamenco art and customs", is a conceptual catchall where flamenco singing and love of bullfighting fit, among other elements Spanish castizos. These customs were strongly attacked by the generation of '98, all of its members being "anti-flamenquistas", with the exception of the Machado brothers, since Manuel and Antonio, being from Seville and sons of the folklorist Demófilo, had a more complex vision. of the matter.

The greatest standard bearer of anti-flamencoism was the Madrid writer Eugenio Noel, who, in his youth, had been a militant casticista. Noel attributed to flamenco and bullfighting the origin of Spain's ills. In his opinion, the absence of these cultural manifestations in modern European states seemed to translate into greater economic and social development. These considerations led to the establishment of an insurmountable rift for decades between flamenco and the majority of the intelligentsia.

Flemish opera

Between 1920 and 1955 flamenco shows began to be held in bullrings and theaters, under the name of "Opera flamenca". This denomination was an economic strategy of the promoters, since the opera only paid 3% while the variety shows paid 10%. At this time, flamenco shows spread throughout Spain and in the main cities of the world. The great social and commercial success achieved by flamenco at this time eliminated some of the oldest and most sober styles from the stage, in favor of lighter airs, such as cantiñas, cantes de ida y vuelta and, above all, fandangos., of which many personal versions were created. Purist critics attacked this lightening of the cantes, as well as the use of falsetto and the vulgar bagpiper style.

In the line of purism, the poet Federico García Lorca and the composer Manuel de Falla had the idea of calling a cante jondo contest in Granada in 1922. Both artists conceived flamenco as folklore, not as a scenic artistic genre; For this reason, they were concerned, because they believed that the massive triumph of flamenco would end its purest and deepest roots. To remedy this, they organized a cante jondo contest in which only amateurs could participate and which excluded festive songs (such as cantiñas), which Falla and Lorca did not consider jondo, but rather flamenco. The jury was chaired by Antonio Chacón, who at that time was a leading figure in cante. The winners were "El Tenazas", a retired professional singer from Morón de la Frontera, and Manuel Ortega, an eight-year-old boy from Seville who would go down in flamenco history as Manolo Caracol. The contest was a failure due to the scant echo it had and because Lorca and Falla failed to understand the professional nature that flamenco already had at that time, striving in vain to seek a purity that never existed in an art that was characterized by the mixture and the personal innovation of its creators. Aside from that failure, with the generation of '27, whose most eminent members were Andalusian and therefore familiar with the genre first-hand, the recognition of flamenco by intellectuals began.

At that time there are already flamenco recordings related to Christmas, which can be divided into two groups: the traditional flamenco carol and flamenco songs that adapt their lyrics to Christmas themes. These songs have been maintained to this day, being Spatially representative, the Zambomba Jerezana, declared an Asset of Intangible Cultural Interest by the Junta de Andalucía in December 2015.

During the Spanish Civil War, a large number of cantaores went into exile or died defending the Republic and the harassment to which they were being subjected by the National Band: Corruco de Algeciras, Chaconcito, El Carbonerillo, El Chato De Las Ventas, Vallejito, Rita la Cantaora, Angelillo, Manuel González López (better known as El Guerrita are some of them. In the postwar period and the first years of Francoism, the world of flamenco was looked at with suspicion, since the authorities were not clear that this genre contributed to the national conscience.However, the regime soon ended up adopting flamenco as one of the Spanish cultural manifestations par excellence.Cantaores who have survived the war go from stars to almost pariahs, singing for the senoritos in the private rooms of the brothels in the center of Seville, where they have to adapt to the whims of aristocrats, soldiers and businessmen who have become rich.

In short, the period of the Flamenco Opera was a time open to creativity and which definitely shaped the majority of the flamenco repertoire. It was the Golden Age of this genre, with figures such as Antonio Chacón, Manuel Vallejo, Manuel Torre, La Niña de los Peines, Pepe Marchena and Manolo Caracol.

The birth of flamencology

As of the 1950s, abundant anthropological and musicological studies on flamenco began to be published. In 1954 Hispavox published the first Antología del Cante Flamenco, a sound recording that was a great shock in its time, dominated by orchestrated singing and, consequently, mystified. In 1955 the Argentine intellectual Anselmo González Climent published an essay called Flamencología , whose title he baptized the "set of knowledge, techniques, etc., on flamenco singing and dancing";. This book dignified the study of flamenco by applying the academic methodology typical of musicology and served as the basis for subsequent studies on this genre.

As a consequence, in 1956 the 1st National Contest of Cante Jondo de Córdoba was organized and in 1958 the first Chair of Flamencology was founded in Jerez de la Frontera, the oldest academic institution dedicated to the study, research, conservation, promotion and defense of flamenco art. Likewise, in 1963 the Cordovan poet Ricardo Molina and the Sevillian singer Antonio Mairena published alalimón Mundo y Formas del Cante Flamenco, which became an obligatory reference work. Using simple language, the book describes the variety of palos and styles, and narrates the history of cante, defending that flamenco was the exclusive work of gypsies, who kept it private until they made it their profession. The book also differentiates between cante grande (merely gypsy) and cante chico (a flamenco style of Andalusian and colonial folkloric tunes). Therefore, the work of Molina y Mairena introduced the "gypsy thesis" and "neojondism" as lines of research.

For a long time, the Mairenista postulates were considered practically unquestionable, until they found an answer in other authors who elaborated the "Andalusian thesis," which defended that flamenco was a genuinely Andalusian product, since it had developed entirely in this region and because its basic styles were derived from Andalusian folklore. They also maintained that the Andalusian gypsies had contributed decisively to their formation, highlighting the exceptionality of flamenco among gypsy music and dances from other parts of Spain and Europe. The unification of the gypsy and Andalusian theses has ended up being the most accepted today. In summary, between the years 1950 and 1970, flamenco went from being a mere spectacle to also becoming an object of study.

Flamenco protests during the Franco regime

Flamenco became one of the symbols of Spanish national identity during the Franco regime, since the regime knew how to appropriate a folklore traditionally associated with Andalusia to promote national unity and attract tourism, constituting what was called national-flamencoism. Hence, flamenco had been seen for a long time as a reactionary or retrograde element. In the mid-60s and up until the transition, singers who opposed the regime began to appear with the use of protest lyrics. Among these we can count: José Menese and the lyricist Francisco Moreno Galván, Enrique Morente, Manuel Gerena, El Lebrijano, El Cabrero, Lole y Manuel, el Piki or Luis Marín, among many others.

In contrast to this conservatism with which it is associated during the Franco regime, flamenco suffered the influence of the wave of activism that also agitated the university against the repression of the regime when the university students came into contact with this art in the recitals that They were held, for example, at the Colegio Mayor de San Juan Evangelista: “flamenco fans and professionals got involved in performances of a manifestly political nature. It was a kind of flamenco protest loaded with contestation, which meant censorship and repression for the flamenco activists”.

As the political transition elapsed, the demands were deflating as flamenco was inserted into the flows of globalized art. At the same time, this art was institutionalized to the point that in 2007 the Junta de Andalucía attributed itself "exclusive competence in matters of knowledge, conservation, research, training, promotion and dissemination".

Flamenco fusion

In the 1970s, Spain was breathing an air of social and political change, and Spanish society was already heavily influenced by various musical styles from the rest of Europe and the United States. There were also numerous singers who had grown up listening to Antonio Mairena, Pepe Marchena and Manolo Caracol. The combination of both factors led to a revolutionary period called Fusión Flamenca.

Singer Rocío Jurado internationalized flamenco in the early 1970s, replacing the bata de cola with evening dresses. Her facet in the & # 34; Fandangos de Huelva & # 34; and in Alegrías she was internationally recognized for her perfect voice range in these genres. She used to be accompanied at her concerts by guitarists Enrique de Melchor and Tomatito, not only nationally but in countries like Colombia, Venezuela and Puerto Rico.

The musical representative José Antonio Pulpón was a decisive figure in that merger, as he urged the singer Agujetas to collaborate with the Sevillian Andalusian rock group Smash, the most revolutionary couple since Antonio Chacón and Ramón Montoya, initiating a new path for the Flemish. It also fostered the artistic union between the virtuous guitarist from Algeciras Paco de Lucía and the long-standing island singer Camarón de la Isla, who gave flamenco a creative boost that would mean its definitive break with Mairena's conservatism. When both artists began their solo careers, Camarón became a legendary singer for his art and personality, with a legion of followers, while Paco de Lucía reconfigured the entire musical world of flamenco, opening up to new influences, such as Brazilian music., Arabic and jazz and introducing new musical instruments such as the Peruvian cajón, the transverse flute, etc.

Other prominent performers in this process of formal renewal of flamenco were Juan Peña El Lebrijano, who paired flamenco with Andalusian music, and Enrique Morente, who throughout his long artistic career has oscillated between the purism of his early recordings and mixing with rock, or Remedios Amaya from Triana, cultivator of a unique style of tangos from Extremadura, and whose purity in her singing makes her part of this select group of established artists.

In 2011 this style became known in India thanks to María del Mar Fernández, who acts in the video clip for the presentation of the film You only live once, titled Señorita. The film was seen by more than 73 million viewers.

The new flamenco

In the 1980s a new generation of flamenco artists emerged who have already been influenced by Camarón, Paco de Lucía, Morente, etc. These artists had a greater interest in popular urban music that in those years was renewing the Spanish music scene, it was the time of the Madrid Movida. Notable among them are Pata Negra, who fused flamenco with blues and rock, Ketama, or La Barbería del Sur, which is pop and Cuban-inspired, and Ray Heredia, creator of his own musical universe where flamenco occupies a central place.

At the end of that decade and throughout the following decade, the Nuevos Medios record company released many musicians under the Nuevo flamenco label, abusing the label "flamenco" for strictly commercial purposes. Thus, this denomination has brought together very different musicians, both orchestrated flamenco performers, as well as rock, pop or Cuban music musicians whose only connection with flamenco is the resemblance of their vocal technique to that of the cantaores, their family origins or his gypsy origin; Examples of these cases can be Rosario Flores, daughter of Lola Flores, or the renowned singer Malú, niece of Paco de Lucía and daughter of Pepe de Lucía, who despite sympathizing with flamenco and keeping it in her discography has continued with her personal style. and has remained in the music industry on its own merits. For the rest, they depart from any classical flamenco structure, having disappeared all traces of the compass, tonal modes and the melodic structures of the styles.

However, the fact that many of the interpreters of this new music are also well-known singers, in the case of José Mercé, El Cigala and others, has led to labeling everything they interpret as flamenco, even though the genre of their songs quite different from classical flamenco. On the other hand, other contemporary artists, such as the groups O'Funkillo and Ojos de Brujo, following the path of Diego Carrasco, use non-flamenco musical styles, but respecting the compass or metric structure of certain traditional styles. There are also encyclopedic singers such as Arcángel, Miguel Poveda, Mayte Martín, Guillermo Cano, Matías López El Mati, Marina Heredia, Estrella Morente or Manuel Lombo who, without renouncing the artistic and economic benefits of fusion and new flamenco, maintain in their interpretations a greater weight of flamenco conceived in the most classical sense of the term, which means a significant return to the origins.

The involvement of the Spanish public authorities in promoting flamenco is growing every day. In this sense, there is the Andalusian Agency for the Development of Flamenco, dependent on the Ministry of Culture of the Junta de Andalucía and currently the City of Flamenco is being built in Jerez de la Frontera, which will house the National Center for Flamenco Art, dependent on the Ministry of Culture and which will aim to channel and organize initiatives on this art. Likewise, the Andalusian autonomous community is studying to incorporate it into its mandatory training plans.

Another aspect to highlight is the gradual incorporation of women into the flamenco world. After a time when great female voices were only allowed to sing in private, a new generation of artists is emerging who, supported by other "weighty" they are winning the stages.

Sing

According to the Royal Spanish Academy, it is called "cante" to the "action or effect of singing any Andalusian song", defining "flamenco singing" like "the agitated Andalusian song" and cante jondo as "the most genuine Andalusian song, with deep feeling". The flamenco singer is called cantaor instead of singer, with the loss of that of intervocalic characteristic of the Andalusian dialect.

The most important award in flamenco singing is probably the Golden Key of Singing, which has been awarded five times to: El Nitri, Manuel Vallejo, Antonio Mairena, Camarón de la Isla and Fosforito.

Touch

The posture and technique of flamenco guitarists, called tocaores, differ from those used by classical guitar players. While the classical guitarist leans the guitar on his left leg, the flamenco guitarist usually crosses his legs and rests it on the one that is higher, placing the neck in an almost horizontal position with respect to the ground. Modern guitarists tend to use classical guitars, although there is a specific instrument for this genre called the flamenco guitar. This is less heavy, and its body is narrower than that of the classical guitar, so its sound is lower and does not overshadow the singer. In general, it is usually made of cypress wood, with a cedar handle and a spruce top. The cypress gives it a bright sound that is very suitable for the characteristics of flamenco. In the past, the palo santo from Rio or India was also used, being the first one of the highest quality, but it is currently in disuse due to its scarcity. The palo santo gave the guitars a breadth of sound especially suitable for solo playing. Currently, the most widely used headstock is metal, since the wooden one poses tuning problems.

The main guitar makers were Antonio de Torres Jurado (Almería, 1817-1892) considered the father of the guitar, Manuel Ramírez de Galarreta, the Great Ramírez (Madrid, 1864-1920), and his disciples Santos Hernández (Madrid, 1873 -1943), who built several guitars for maestro Sabicas, Domingo Esteso and Modesto Borreguero. Also noteworthy are the Conde brothers, Faustino (1913-1988), Mariano (1916-1989) and Julio (1918-1996), nephews of Domingo Esteso, whose sons and heirs continue the saga.

Tocaores use the alzapúa, picado, strumming and tremolo techniques, among others. One of the first toques that is considered flamenco, such as the "rondeña", was the first recorded composition for solo guitar, by Julián Arcas (María, Almería, 1832 - Antequera, Málaga, 1882) in Barcelona in the year 1860. The strumming can be done with 5, 4 or 3 fingers, the latter invented by Sabicas. The use of the thumb is also characteristic in flamenco playing. Guitarists rest their thumb on the soundboard of the guitar and their index and middle fingers on the string above the one they are playing, thus achieving greater power and sound than the classical guitarist. The middle finger is also supported on the guitar pickguard to achieve more precision and strength when plucking the string. Likewise, the use of the beater as a percussion element gives great strength to the flamenco guitar interpretation. It is called "falseta" to the melodic phrase or flourish that is inserted between the chord successions intended to accompany the copla. There is also talk of playing or accompanying above (using the fingering of the E major chord) and through the middle (A major), regardless of whether or not it has been transported with the capo.

The accompaniment and solo playing of flamenco guitarists is based on both the modal and tonal harmonic systems, although most often it is a combination of both. Some flamenco songs are interpreted "a dry stick" (a cappella), without guitar accompaniment.

Depending on the type of interpretation, we speak of:

- Airy touch: vivacious, rhythmic and bright, almost metallic sound.

- Gypsy or flamenco touch: hondo and with pinch, preferably use the boards and setbacks.

- Toque pastueño: slow and quiet.

- Sober knock: without ornaments or superfluous alards.

- Virtuous touch: with exceptional mastery of the technique, you run the risk of falling into a demeasured effect.

- Short score: poor in technical and expressive resources.

- Cold touch: devoid of mushroom and pinch.

Dance

Flamenco dance can accompany different styles. Its performance is similar to a moderate physical exercise, and has proven effects on physical and emotional health (called "flamencotherapy").

The regulated teaching of flamenco in educational centers

In Spain, regulated flamenco studies are officially taught in various music conservatories, dance conservatories and music schools in various autonomous communities.

Music conservatories

Flamenco guitar studies in official educational centers began in Spain in 1988 at the hands of the great soloist and teacher from Granada, Manuel Cano Tamayo, who obtained a position as emeritus professor at the Rafael Orozco Superior Conservatory of Music in Córdoba.

There are conservatories specialized in flamenco throughout the country, although mainly in the region of Andalusia, such as the aforementioned Conservatory of Córdoba, the Conservatory of Music of Murcia or the Escola Superior de Música de Catalunya, among others. Outside of Spain, a unique case is the Rotterdam Conservatory, in the Netherlands, which offers regulated flamenco guitar studies under the direction of maestro Paco Peña since 1985, a few years before they existed in Spain.

University

In 2018 the first Interuniversity Master's Degree in Research and Analysis of Flamenco began, after previous attempts at the "Doctoral Program for an Approach to Flamenco", taught by various universities such as Huelva, Seville, Cádiz and Córdoba, among other.

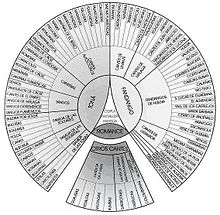

Sticks

The palo is known as "each of the traditional varieties of flamenco singing". Each palo has its own name, unique musical characteristics called "keys" or "modes", a certain harmonic progression and some rhythmic schemes called "compás". The styles can be classified according to several criteria: according to their compass, their jondura, their serious or festive character, their geographical origin, etc.

The styles are divided according to their rhythmic aspect as follows:

- Binario/Cuaternario: Tanguillos, Colombianas, Rumba, Tangos, Tientos, etc.

- Ternario: Sevillanas, Campanilleros, Fandangos libre, de Huelva, etc.

- Amalgam I: Joys, Soleá, Soleá for bulerías, etc.

- Amalgam II: Guajira, Peteneras, Bulerias, etc.

- Amalgam III: Cabals, Sigaiya, Liviana, etc.

History

The fandango, which in the 17th century was the most widespread song and dance throughout Spain, over time ended up generating local and regional variants, especially in the province of Huelva, where there are more than forty different styles. In Alta Andalucía and neighboring areas, the fandangos were accompanied with the bandola, an instrument with which they accompanied themselves following a regular beat that allowed dancing and from whose name the "abandolao" style derives. This is how the fandangos from Lucena, the drones from Puente Genil, the malagueñas primitivas, the rondeñas, the jaberas, the jabegotes, the verdiales, the chacarrá, the granaína, the taranto and the taranta arose. Due to the expansion of the sevillanas in Baja Andalucía, the fandango gradually lost its role as a support for the dance, which allowed the singer to show off and be more free, generating a multitude of personally created fandangos in the 20th century. Likewise, thousands of Andalusian peasants, especially from the provinces of Eastern Andalusia, emigrated to the Murcian mining sites, where the tarantos and tarantas evolved. The Taranta de Linares, evolved into the Minera de la Unión, the Cartagena and the Levantica. In the days of the cafés cantantes, some of these songs were separated from the dance and acquired a free rhythm, which allowed the performers to show off. The great promoter of this process was Antonio Chacón, who developed precious versions of malagueñas, granaínas and mining songs.

The stylization of romance and string sheets gave rise to the corrido. The extraction of the romances of cuartetas or three significant verses gave rise to the primitive tonás, the caña and the polo, which share metrics and melody, but differ in their execution. The guitar accompaniment gave them a beat that made them danceable. It is believed that their origin was in Ronda, a city in Alta Andalucía close to Baja Andalucía and closely related to it, and that from there they arrived in the Sevillian suburb of Triana, with a great tradition of corridos, where they were transformed into the soleá. From the festive interpretation of corridos and soleares, the jaleos arose in Triana, which traveled to Extremadura and which in Jerez and Utrera led to the bulería, from where they spread throughout Lower Andalusia, generating local variants.

In the great Andalusian ports of Cádiz, Málaga and Seville, tangos and tientos were developed, which have a great influence from black American music. Also in Cádiz the group of cantiñas was generated whose central palo is joy.

Some popular Andalusian tunes, such as the pregones, the lullabies and peasant threshing songs, have the same metrics as the flamenco seguidillas. From them the liviana and the serrana could arise, which is a virtuoso and melismatic interpretation of the liviana; in fact, they are traditionally performed together. This group of styles also belongs to the alboreá and the old playa, which was impregnated with the melody of the tonás, giving rise to the seguidillas, which included guitar accompaniment.

Classification

Alphabetic

Dawn | joys | bambera | Bandola | bulerías | Cabales | bell ringers | canteen | Cane | snails | Jailer | Cartagena | puff | Colombian | Andalusian couplet | Corrios | Debla | Fantasy | Fandango | fandanguillo | Farruca | galleys | garrotin | granaine | Guajira | Jabegote | Jabera | Flamenco jack | Light | Malaga | Marian | Piledriver | Mean | Half Grenaina | Milonga | mining | Mirabras | Murcian | lullaby | Petenera | Pole | Romance | Pilgrimages | Rondena | Rumba | Bolt | Seguiriya or Siguiriya | mountain ranges | Sevillian | soleá | tango | tanguillo | Taranta or Taranto | tientos | Tona | Thresher | Verdiales | Vidalita | Zambra | stomping | Zorongo

According to the metric of music

Palos can be divided into five groups from the point of view of metrics, depending on their time signature:

- Metric of 12 times (amalgamation of 6/8 and 3/4) That in turn they divide into those who use the:

- soleá compas: soleá, soleá por bulerías, bulerías, bulerías por soleá, joys, rod, pole, mirabrás, caracoles, romera, cantiñas, bambera, alboreá, romance, zapateado catalán.

- Compás de seguiriya: followiyas, horsemen, light, sawn, toná-liviana.

- And in the guajira and the petenera, they use the so-called amalgam in a simple way.

- Binaria and Quaternary Metric: taranta or taranto, tientos, mariana, dance, tangos, zambra, farruca, garrotín, rumba, danzón, colombiano, milonga.

- Alternative metric: fandango de Huelva, fandango malagueño, sevillanas, verdiales.

- Polyrrhythmic metric: tanguillo and zapateado.

- Free metric (ad líbitum): toná, debla, martinete, carcelerate, camper songs, saeta, malagueña, granaine, media granaine, rondeña, cantes de las minas (minera, taranta, cartagenera, levantica, murciana).

According to the metric of the couplets

Based on the metric of the couplets, the styles can be divided into three large groups, those that use:

- The romance: three or four verses of eight syllables, with rhyme preferably sounded in the pair verses.

- La followed: flanges of three or four alternate verses of five and seven syllables, with rhyme in the short verses.

- The fandango: five verses of seven or eight syllables, rimando the pairs and the odds separately. At the time of execution one of the verses is repeated.

According to their musical origin

The songs that derive from:

- Romances and followers are: run, toná, seguiriya, saeta, martinete, carcelerate, debla, light and horse riding.

- Fandangos are: fandangos, malagueña, verdiales, jabera, rondeña, granain, media granain, bandolá, jabegote, minera, murciana, cartagenera and taranta.

- Coplas y canciones Andaluzas del siglo XVIIIare: tangos, tientos, tanguillos, cane and pole.

- Cantes camperos Andaluces are: saws, trilleras, nanas, marianas, campanilleros, cachuchas, El vito y las sevillanas corraleras.

- Dance singers are: soleá, bulerías, petenera, alboreá y todas las cantiñas (alegrías, mirabrás, caracoles y romeras).

- American Black Songs are: Colombian, rumba, guajira, milonga. Some authors consider that fandango, tanguillos, bulerías and la seguiriya also have African origin.

- Not Andalusian Spanish folklore are: farruca, garrotín and jota flamenca.

According to geographical origin

Based on their geographical origin, they can be divided into:

- Cantes de Cádiz y los Puertos;

- Cantes de Málaga;

- Cantes de Levante;

- Round-trip glasses.

According to the musical texture

The songs "a dry stick" (a capella, without guitar accompaniment) are the jailers, the debla, the martinete, the pregones, the saeta, the tonás and the trilleras. The rest are usually accompanied by guitar.

Most basic flamenco styles

Cantinas

It constitutes the flamenco style that most accurately expresses the feeling of the Cádiz environment.

Bulerías

It stands out for being a party style, with a fast and redoubled rhythm and that lends itself more than others to ruckus and clapping. This is usually the dance with which the flamenco revelry ends, where the dancers, usually one by one, form a semicircle, go out to the center to dance a part of the musical piece.

Fandangos

Since the beginning of the 19th century, flamenco adopted features of the Andalusian fandangos, thus giving rise to the so-called “flamenco fandangos” in 3/4 time, which are considered today as one of the fundamental styles of flamenco. Within the immense variety of existing fandangos, the natural fandangos and the Huelva fandangos stand out.

Tangos

Tangos are considered one of the basic styles of flamenco, and there are several modalities.

Songs from the Levante

Group of songs of great influence in malagueñas and granaínas, and among which are songs typical of Murcia.

Lexicon

Okay

Adolfo Salazar states that the expressive voice ole, with which Andalusian cantaores and bailaores animate, can come from the Hebrew verb oleh meaning "pull up," making it clear that the whirling dervishes of Tunisia also dance around to repeated "ole" or "joleh". The use of the word "arza", which is the Andalusian dialectal way of pronouncing the imperative voice "alza", seems to point in this same direction. with the characteristic Andalusian equalization of the implosive /l/ and /r/. The indiscriminate use of the words "arza" and "ole" when it comes to jalear flamenco cantaores and bailaores, so they could be interpreted as synonymous voices. But the most evidence of the origin of this word may be from caló: Olá, which means Come on. Likewise, in Andalusia, hunting hunting is known as jaleo, that is, the action of hunting, which is to "scare away game with voices, shots, blows or noise, so that it gets up".

Apart from the origin and meaning of the expression "ole", there is a type of Andalusian popular song named for the characteristic repetition of said word. Falla was inspired by this type of song in some passages from the second act of his opera La vida breve.

Goblin

According to the RAE dictionary (1956!) the "goblin" in Andalusia it is a "mysterious and ineffable charm", a charisma that the gypsies call duende. defining it with the following words of Goethe: "Mysterious power that everyone feels and that no philosopher explains". In the flamenco imaginary, the duende goes beyond technique and inspiration, in the words of Lorca "To look for the duende there is no map or exercise". When a flamenco artist experiences the arrival of this mysterious charm, the expressions "tener duende" or sing, play or dance "with duende".

Along with those mentioned above, there are many other words and expressions characteristic of the flamenco genre, such as "cuadro flamenco","tablao flamenco", "juerga flamenca&# 34;, "tercio", "aflamencar", "aflamencamiento", "flamencología"...

Contenido relacionado

Herod I the Great

Dec. 24

Gules