First punic war

The First Punic War (264-241 BC) was the first of three wars fought between Carthage and Rome, the two major powers in the western Mediterranean at the turn of the century III a. C. The war lasted 23 years, making it the longest continuous conflict and the largest naval war in antiquity between the two powers that fought for supremacy. The wars were fought mainly on the Mediterranean island of Sicily and its surrounding waters, and also in North Africa. After immense material and human losses on both sides, the Carthaginians lost the war.

The war began in 264 B.C. C. when the Romans seized Messina, in Sicily. The Romans then pressured Syracuse, the island's only significant independent power, into allying with them and besieged Carthage's main base, Agrigento. A large Carthaginian army attempted to lift the siege in 262 BC. C., but suffered a serious defeat in the homonymous battle. The Romans then built an army to challenge the Carthaginians, and using novel tactics, inflicted several setbacks on them. They took a Carthaginian base in Corsica, but the Carthaginians repulsed the subsequent attack on Sardinia, in which the Romans also lost the Corsican base.

Building on their naval victories, the Romans dispatched a fleet to invade North Africa, which the Carthaginians tried to intercept. However, they suffered a new setback in the Battle of Cape Ecnomo, in what was possibly the largest naval battle in history by the number of combatants. The Roman invasion went well to start and in 255 B.C. C. the Carthaginians asked for peace, but the conditions demanded by the enemy were so harsh that they chose to continue fighting and defeated the invaders. The Romans sent a fleet to evacuate their survivors and were opposed by the Carthaginians at the Battle of Cape Hermeus, where they suffered another heavy defeat. A storm destroyed the Roman fleet as it returned to Italy; the squadron lost most of its ships and over a hundred thousand men.

The war continued, with neither side able to gain a decisive advantage. The Carthaginians attacked and recaptured Agrigento in 255 BC. C., but they believed that they could not control the city, so they razed it and abandoned it. The Romans quickly rebuilt their fleet, adding 220 new ships, and conquered Panormo—present-day Palermo—in 254 BC. C., but the following year, they lost one hundred and fifty ships to a storm. The Carthaginians tried to recapture Panormo in 251 BC. C., but they lost the battle that was fought next to the walls. Slowly, in 249 B.C. C., the Romans occupied most of Sicily and besieged the last two Carthaginian fortresses, at the western end of the island. They also attacked the enemy fleet by surprise, but were defeated in the battle of Drépano. This Carthaginian victory was followed by that of the Phintias, a battle in which the Romans lost most of their remaining warships. After several years of stalemate, the Romans rebuilt their fleet again in 243 BC. C. and effectively blocked the Carthaginian garrisons. Carthage assembled a fleet with which to help them, which ended up being destroyed in the Battle of the Aegadian Islands in 241 BC. C., which forced the isolated Carthaginian troops in Sicily to negotiate peace.

Finally a treaty was agreed whereby Carthage paid large indemnities and Rome annexed Sicily as a province. From then on, the Roman Republic was the main military power in the western Mediterranean and, increasingly, in the Mediterranean region as a whole. The immense effort of building a thousand galleys during the war laid the foundation for Rome's maritime dominance for six hundred years. The end of the war sparked a major but unsuccessful revolt within Carthage. The unresolved strategic competition between Rome and Carthage led to the outbreak of the Second Punic War in 218 BC. c.

Fonts

The term Punic comes from the Latin word Punicus (or Poenicus), whose meaning is “Carthaginian”, and is a reference to the Phoenician ancestry of the Carthaginians. The primary source for almost all aspects of the First Punic War is the historian Polybius (c. 200-c. 118 BCE), a Greek sent to Rome in 167 BCE. as a hostage His works include a now-lost manual on military tactics, but he is known today for The Histories, written sometime after 146 BC. C., or about a century after the end of the war. Polybius's work is widely considered to be objective and neutral between Carthaginian and Roman points of view.

Carthaginian written records were destroyed along with their capital, Carthage, in 146 B.C. Thus Polybius's account of the First Punic War is based on various Greek and Latin sources, now lost. Polybius was an analytical historian and whenever possible personally interviewed the participants in the events he wrote about.. Only the first book of the forty that comprises The Histories deals with the First Punic War. The accuracy of his account has been much debated over the past hundred and fifty years, but the modern consensus is accepting it largely at face value, and details of the war in modern sources are based almost entirely on interpretations of Polybius's account. Modern historian Andrew Curry considers "Polybius turns out to be quite reliable".; while Dexter Hoyos describes him as "a remarkably well-informed, hard-working and perceptive historian". Other later histories of the war exist, but in fragmentary or abridged form. Modern historians they usually take into account the fragmentary writings of various Roman analysts, especially Tito Livio —who was based on Polybius—; the Sicilian Greek Diodorus Siculus; and later Greek writers Appian and Cassius Dio. Classicist Adrian Goldsworthy states that "Polybius's account is usually preferred when it differs from any of our other accounts." Other sources include inscriptions, terrestrial archaeological evidence, and empirical evidence from reconstructions. such as the Olympias trireme.

Since 2010, archaeologists have found nineteen bronze rams from warships in the sea off the west coast of Sicily, a mix of Roman and Carthaginian, ten bronze helmets and hundreds of amphorae. The spurs have since been recovered, seven of the hulls and six of the amphorae intact, along with a large number of fragments. The spurs are believed to have been attached to a sunken warship when it sank to the seabed. The archaeologists involved claimed that the location of the artifacts discovered so far supports Polybius's account of where the Battle of the Aegadian Islands took place. Based on the dimensions of the recovered spurs, archaeologists who have studied them believe that they all came from of triremes, contrary to what Polybius says that all the warships involved were quinqueremes. However, they believe that the numerous identified amphorae confirm the accuracy of other aspects of Polybius's account of this battle: "It is the sought-after convergence of the archaeological and historical records."

Situation

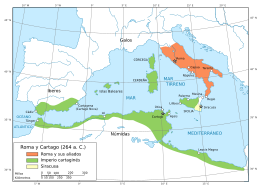

The Roman Republic was hostilely expanding in southern mainland Italy for a century before the First Punic War. It conquered mainland Italy south of the Arno River in 272 BC. When the southern Greek cities—Magna Graecia—submitted at the end of the Pyrrhic War. During this period, Carthage, with its capital in what is now Tunis, came to dominate southern Spain, much of the coastal regions of North Africa, the Balearic Islands, Corsica, Sardinia and the western half of Sicily, territories integrated into a military and commercial empire. From 480 BC. C., Carthage had waged a series of wars of uncertain outcome against the Greek city states of Sicily, led by Syracuse. By 264 B.C. C. Carthage and Rome were the pre-eminent powers in the western Mediterranean. The two states had several times affirmed their mutual friendship in official alliances: in 509 B.C. C., 348 B.C. C. and around 279 B.C. C. Relations between them were good and they had strong commercial ties. During the Pyrrhic War of 280-275 B.C. C., against a king of Epirus who fought alternately against Rome in Italy and Carthage in Sicily, the latter providing resources to the Romans and on at least one occasion used its navy to transport a Roman contingent.

In 289 B.C. In BC, a group of Italian mercenaries known as the Mamertines, previously hired by Syracuse, occupied the city of Mesana—present-day Messina—in the far northeast of Sicily. Under pressure from Syracuse, the Mamertines appealed to both Rome and Carthage for help in 265 B.C. The Carthaginians acted first, urging Hiero II, King of Syracuse, to take no further action and to convince the Mamertines to accept a Carthaginian garrison. According to Polybius, considerable debate ensued in Rome over whether to accept the request. help from the Mamertines. As the Carthaginians had already garrisoned Mizana, acceptance could easily lead to war with Carthage. The Romans had previously shown no interest in Sicily and did not wish to come to the aid of soldiers who had unjustly seized a city from its rightful possessors. However, many of them saw strategic and monetary advantages in gaining a foothold in Sicily. The deadlocked Roman Senate, possibly at the behest of Appius Claudius Caudex, took the matter to the popular assembly in 264 BC. C. Cáudex encouraged a vote in favor of the action and offered the prospect of abundant booty; the popular assembly decided to accept the request of the Mamertines; Cáudex was appointed head of a military expedition, with orders to go to Sicily and place a Roman garrison in Mizana.

The war began when the Romans landed on Sicily in 264 BC. The Carthaginian naval advantage was not enough to prevent the Roman crossing through the Strait of Messina. Two legions commanded by Caudex marched to Mesana, where the Mamertines had driven out the Carthaginian garrison of Hannon—unrelated to Hannon the Great—and suffered a joint Carthaginian and Syracusan siege. The sources are unclear as to why, but first the Syracusans and then the Carthaginians withdrew from the site. The Romans marched south and, in turn, besieged Syracuse, but soon withdrew, lacking sufficient forces and secure supply lines, prerequisites for surrendering the city. The experience of the Carthaginians over the previous two centuries of war in Sicily indicated that it was not possible to fight a decisive battle: the armies were exhausted due to heavy losses and enormous expenses; this made the Carthaginian leaders hope that this war would follow a similar course to the previous ones they had fought on the island. Meanwhile, their overwhelming maritime superiority would allow the war to be fought far from the core of the Punic Empire, which could continue to prosper despite the strife. This allowed the Carthaginians to raise and pay for an army that would operate in the open against the Romans, while that its heavily defensed cities could be supplied by sea and serve as a defensive base from which to operate.

Armies

Adult male Roman citizens were chosen for military service; the majority served as infantry, while the wealthier minority contributed the cavalry contingent. Traditionally, the Romans recruited two legions, each of 4,200 foot and 300 cavalry. A small part of the infantry was made up of skirmishers armed with javelins. The rest were equipped as heavy infantry, with armor, a large shield and short sword. The infantrymen were divided into three ranks, of which the first rank also carried two javelins, while the soldiers of the second and third carried a spear instead. Both legionary subunits and individual legionnaires fought in a relatively open order. Typically, an army was formed by combining a Roman legion with another of similar size and equipment provided by the Latin allies.

Carthaginian citizens only served in the military if there was a direct threat to the city. In most circumstances, the Carthaginian army was drawn from foreigners, many from North Africa, who provided various specialized troops, including: infantry organized in close formation, equipped with large shields, helmets, short swords and long spears, and skirmishers. light infantry armed with javelins; shock cavalry also fighting in close formation—also known as "heavy cavalry"—carrying lances; and light cavalry skirmishers who hurled javelins from afar and avoided close combat. Both Spain and Gaul provided veteran infantry: unarmed troops who charged fiercely, though they had a reputation for surrendering if combat dragged on. part of the Carthaginian infantry fought in a compact formation known as a phalanx, usually of two or three lines. Specialized slingers were recruited from the Balearic Islands. The Carthaginians also used war elephants; North Africa was then inhabited by African forest elephants. It is unclear from the sources whether they carried turrets to transport warriors.

Navy

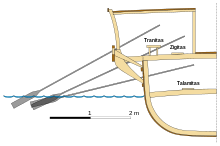

Quinqueremes, five-oared ships as the name suggests, were the main ships of the Roman and Carthaginian fleets during the Punic Wars. So ubiquitous was this type of ship that Polybius uses it as an abbreviation for "warship". » in general. A quinquereme carried a crew of three hundred men: two hundred and eighty oarsmen and twenty crew and deck officers. It also normally carried a complement of forty marines – usually soldiers assigned to the ship – which increased to one hundred twenty if battle was thought to be imminent.

Getting the oarsmen to row as a unit, let alone perform more complex battle maneuvers, required long and arduous training. At least half of the oarsmen needed to have had some experience for the ship to handle effectively. As a result, the Romans were initially at a disadvantage to the more experienced Carthaginians at sea. To counteract this, the Romans introduced the corvus, a bridge 1.2 meters wide and 11 meters long, with a heavy spike at the bottom, which was designed to pierce and anchor into the deck of enemy ship. It allowed legionnaires acting as marines to board enemy ships and seize them, rather than employing the earlier traditional tactic of ramming them with the bow ram.

All warships were equipped with battering rams, a triple set of bronze sheets two feet wide and up to five hundred pounds in weight that were placed on the waterline. In the century before the Punic Wars, boarding had become increasingly common and ramming had diminished, as the larger and heavier vessels adopted in this period lacked the necessary speed and maneuverability for ramming, while their construction more robust reduced the effect of the ram even in case of direct impact. The Roman adoption of the corvus was a consequence of this trend and made up for its initial disadvantage in navigation. The additional weight at the bow compromised both the ship's maneuverability and seaworthiness, and in rough seas the corvus became useless.

Sicily 264-256 BC. c

Much of the war was fought in Sicily or in nearby waters. Far from the coast, its broken terrain made it difficult for large armies to maneuver and favored defense over offense. Land operations were largely limited to raids, sieges, and harassment; in twenty-three years of war in Sicily there were only two large-scale pitched battles: that of Agrigento in 262 B.C. C. and that of Palermo in 250 BC. Garrisoning and land blockades were more common operations for both armies than open field battles.

Since ancient times, the Romans appointed two military chiefs, the consuls, each year to each command an army. At two of the year 263 a. He dispatched them to Sicily at the head of forty thousand soldiers. Syracuse suffered a new siege and, as he did not expect to receive any Carthaginian help, he hastened to make peace with the Romans: he became a Roman ally, paid an indemnity of one hundred talents of silver and, perhaps most importantly, he agreed to help supply the Roman army in Sicily. After Syracuse's defection, several small Carthaginian dependencies fell into Roman hands. The Carthaginians made Agrigento, a port city in the middle of the southern coast of Sicily, its strategic center, for which the Romans marched on it in 262 BC. and besieged it. The besiegers had an insufficient supply system, partly because Carthaginian naval supremacy prevented them from sending supplies by sea, and also because they were not used to feeding an army of forty thousand men. Most of the army spread out over a wide area when harvest time came, both to participate in this work and to gather food. The Carthaginians, commanded by Aníbal Gisco, attacked them with force, took them by surprise and penetrated their camp, but the Romans gathered and defeated them. After this combat, both sides became more cautious.

Meanwhile, Carthage recruited an army whose command he handed over to Hanno, son of Hannibal, made up of fifty thousand infantry, six thousand cavalry and sixty elephants, made up partly of Ligurian, Celtic and Iberian mercenaries, which was assembled in Africa and it was sent to Sicily. Hanno marched to the aid of Agrigento five months after the siege began. When he arrived, he simply camped on high ground, engaged in unrelated skirmishes, and devoted himself to training his army; after two months, in the spring of 261 BC. C., he finally attacked, but was defeated and suffered heavy losses at the Battle of Agrigento. The Romans, under both consuls, Lucius Postumius Megelus and Quintus Mamilius Vitulus, pursued him and seized the elephants and Carthaginian supplies. That night the Carthaginian garrison escaped while the Romans were distracted, and the next day the latter took over the city and its inhabitants; they sold twenty-five thousand of them into slavery.

After this Roman triumph, the war fizzled out for several years: both sides won minor victories, but both lacked a clear war objective. In part this was because the Romans poured much of their resources into an ultimately unsuccessful campaign against Corsica and Sardinia, and then the equally barren expedition to Africa. After taking Agrigento, they moved west to lay siege to Mytistratus for seven months., without success. In 259 B.C. C. they headed for Thermae (present-day Termini Imerese) on the north coast, but, as a result of a dispute with the allies, they and the Romans camped separately. Hamilcar took advantage of it to launch a counterattack that surprised one of the two groups of enemies when he was preparing to break camp; the Carthaginian onslaught inflicted between four and six thousand dead on the Romans. Hamilcar went on to take Enna, in central Sicily, and Camarina, in the south-east, dangerously close to Syracuse, and seemed close to taking all of Sicily. The following year, the Romans retook Enna and eventually conquered Mytistratus.; then they moved to Panormo -the modern Palermo-, but they had to withdraw, although they took Hipana and in 258 a. C. recaptured Camarina after a long siege. During the following years, small raids, skirmishes and the occasional change of sides of one of the smaller cities continued in Sicily.

Rome builds a fleet

The war in Sicily reached a stalemate as the Carthaginians concentrated on defending their cities and towns; these were mostly on the coast and could therefore be supplied and reinforced without the Romans being able to use their army to intercept them. The focus of the war shifted to the sea, where the Romans had little experience; on the few occasions when they had previously felt the need for a naval presence, they had usually relied on small squadrons provided by their Latin or Greek allies. In 260 BC. In BC, the Romans set out to build a fleet and used a wrecked Carthaginian quinquereme as a model for their ships. As novice shipbuilders, the Romans built copies that were heavier than Carthaginian vessels and therefore slower and more efficient. less manoeuvrable.

The Romans built 120 warships and sent them to Sicily in 260 BC. C. for their crews to carry out basic training. One of the consuls of the year, Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio Asina, sailed with the first 17 ships to reach the Lipari Islands, a little off the northeast coast of Sicily, in an attempt to seize the islands' main port, Lipara. The Carthaginian fleet was commanded by Aníbal Gisco, the general who had commanded the Agrigento garrison, and was based in Palermo, about 100 kilometers from Lipara. When Hannibal heard about the movement of the Romans, he sent 20 ships under the command of Boodes towards the town, they arrived at night and trapped the Romans in the port. Boodes's ships attacked and Scipio's inexperienced men offered little resistance, resulting in them panicking and fleeing inland whereupon they took the consul himself prisoner and captured all the Roman ships, most with little damage. A little later, Hannibal was scouting with 50 Carthaginian ships when he came across the entire Roman fleet. He escaped, but lost most of his ships, it was after this skirmish that the Romans installed the corvus on his ships.

Scipio's fellow consul, Gaius Duilius, placed the Roman army units under subordinates, took command of the fleet, and sailed quickly, seeking battle. The two fleets met off the coast of Milazzo at the Battle of Milas, Hannibal had 130 ships, and historian John Lazenby estimates that Duilio had roughly the same number. The Carthaginians anticipated victory, due to the superior experience of their forces. crews, and their fastest and most maneuverable galleys, broke formation to rapidly close with the Romans. The first 30 Carthaginian ships came under the grip of the corvus and were successfully boarded by the Romans, including the Hannibal's ship, although he escaped in a skiff. Seeing this, the remaining Carthaginians spread wide open and tried to beat the Romans from the sides or rear, but the Romans counter-attacked successfully and captured another 20 Carthaginian vessels. The surviving Carthaginians broke up the action and, being faster than the Romans, they were able to escape. Duilius set sail to relieve the Roman city of Segesta, which had been under siege.

From the beginning of 262 B.C. In BC, Carthaginian ships had raided the Italian coast from their bases in Sardinia and Corsica. The year after Milas, 259 BC. C., the consul Lucio Cornelio Escipión led part of the fleet against Aléria in Corsica and captured it. He then attacked Olbia in Sardinia, but they repulsed the attack, causing him to lose Aléria.In 258 BC. In C. C., a stronger Roman fleet engaged a smaller Carthaginian fleet at the Battle of Sulci off the town of Sulci in western Sardinia and inflicted a heavy defeat. The soldiers of the Carthaginian commander Aníbal Gisco, who abandoned them and fled to Sulci, later captured him and was crucified. Despite this victory, the Romans, who were attempting to support simultaneous offensives against Sardinia and Sicily, were unable to exploit it, and the attack on Carthaginian-controlled Sardinia petered out.

In 257 B.C. BCE, the Roman fleet was anchored off Tyndaris, in north-eastern Sicily, when the Carthaginian fleet, unaware of their presence, sailed in open formation. The Roman commander, Cayo Atilio Régulo Serrano, ordered an immediate attack, so the battle of Tíndaris began. This led to the Roman fleet in turn going to sea in disorder. The Carthaginians responded quickly; they rammed and sank nine of the ten main Roman ships. When the main Roman force went into action, they sank eight Carthaginian ships and captured ten. The Carthaginians withdrew, again faster than the Romans and therefore able to escape without further loss. The Romans then stormed both Lipari and Malta.

Invasion of Africa

2: Roman victory in Aspis. (256 BC)

3: The Romans capture Tunisia. (256 BC)

4: Jantype part of Carthage with a great army. (255 BC)

5: The Romans are defeated in the battle of Tunisia. (255 BC)

6: The Romans retire to Aspis and leave Africa. (255 BC)

Their naval victories at Milas and Sulci, and their frustration at the stalemate in Sicily, led the Romans to adopt a sea-based strategy and develop a plan to invade the Carthaginian heartland in North Africa and threaten Carthage — near Tunis. Both sides decided to establish naval supremacy and invested large amounts of money and manpower to maintain and increase the size of their navies. The Roman fleet of 330 warships and an unknown number of transports set sail from Ostia, the port of Rome, in early 256 B.C. C., commanded by the consuls of the year, Marco Atilio Regulo and Lucio Manlio Vulson Longo. The Romans planned to cross the Mediterranean Sea and invade what is now Tunisia, shortly before the battle, they embarked approximately 26,000 legionaries of the forces Romans in Sicily.

The Carthaginians knew the intentions of the Romans and assembled all their 350 warships under the command of Hanno the Great and Hamilcar, off the southern coast of Sicily to intercept them. With a combined total of around 680 warships carrying up to 290,000 crew members and marines, the ensuing Battle of Cape Ecnomo was arguably the largest naval battle in history by the number of combatants involved. After the battle, the Carthaginians seized the initiative in the hope that their naval skills, superior to those of the Romans, would benefit them in battle. After a day of protracted and confused fighting, the Carthaginians were ultimately defeated, in which 30 ships were sunk and the Romans captured 64, although 24 of their ships were also sunk.

After the victory, the Roman army, commanded by Marcus Attilius Regulus, landed in Africa near Aspis—present-day Kélibia—on the Cape Bon peninsula and began to devastate the Carthaginian camp. After a brief siege, Aspis was captured. Most of the Roman ships returned to Sicily, leaving Regulus with 15,000 infantry and 500 cavalry to continue the war in Africa; Regulus besieged the city of Addis. The Carthaginians recalled Hamilcar from Sicily with 5,000 infantry and 500 cavalry and put him in command, along with Hasdrubal and a third general named Bostar, of an army about the same size as the Roman force, which was strong in cavalry and elephants. The Carthaginians established a camp on a hill near Addis, and the Romans carried out a night march and launched a surprise dawn attack on them from two directions. After confused fighting, the Carthaginians broke up and fled, although their losses are unknown, their elephants and cavalry escaping with few casualties.

The Romans went on and captured Tunis, just 10 miles from Carthage. From Tunis the Romans raided and devastated the immediate area around Carthage. Desperate, the Carthaginians sued for peace, but Regulus offered such harsh terms that the Carthaginians decided to continue fighting. They handed over the training of their army to the Spartan mercenary commander Xantipo. C., Jantipo led an army of 12,000 infantry, 4,000 horsemen, and 100 elephants against the Romans and defeated them at the Battle of Tunis. Approximately 2,000 Romans withdrew to Aspis, though 500 were captured, including Regulus, and the rest were killed. Xanthippus, fearful of the envy of the Carthaginian generals he had outmaneuvered, accepted his pay and returned to Greece. The Romans sent a fleet to evacuate their survivors, but a Carthaginian fleet intercepted them off Cape Bon—in the north-east. of present-day Tunis—and at the Battle of Cape Hermaeum the Carthaginians suffered a fierce battle, losing 114 captured ships. A storm devastated the Roman fleet as it returned to Italy, with 384 ships sunk out of a total of 464 and 100,000 men lost, mostly non-Roman Latin allies. It is possible that the presence of the corvus made Roman ships unusually unseaworthy and there is no record of their being used after this disaster.

Sicily 255-248 BC. c

Having lost most of his fleet in the storm of 255 B.C. C., the Romans quickly rebuilt it and added 220 new ships. In 254 B.C. The Carthaginians attacked and captured Agrigento, but with little hope of controlling the city, they burned it, razed its walls, and left. Meanwhile, the Romans launched an offensive into Sicily. His entire fleet, commanded by both consuls, attacked Panormo earlier in the year, surrounding and blockading the city and installing siege weapons. These breached the walls which the Romans stormed, capturing the outer city and giving no quarter, prompting the city center to quickly surrender. The 14,000 people who could afford it paid their own ransom and sold the remaining 13,000 into slavery. Much of the western interior of Sicily fell into Roman hands: Ietas, Solunte, Petra and Tindaris came to terms.

In 253 B.C. C., the Romans again shifted their focus to Africa and carried out several raids. They lost another 150 ships, out of a fleet of 220, in a storm returning from attacking the North African coast east of Carthage, but ended up rebuilding it again. The following year, the Romans turned their attention to northwestern Sicily, for so they sent a naval expedition to Lilibea. Along the way, the Romans took and burned the Carthaginian cities of Selinunte and Heraclea Minoa, but were unable to seize Lilibea. In 252 B.C. They captured Thermae and Lipara, which had been cut off by the fall of Panormo, but avoided battle in 252 and 251 BC. C., according to Polybius because they feared the war elephants that the Carthaginians had sent to Sicily.

In the late summer of 251 B.C. When learning that a consul had left Sicily to spend the winter with half the Roman army, the Carthaginian commander Hasdrubal, who had faced Regulus in Africa, advanced on Panormo and devastated the fields. The Roman army, which had dispersed to gather the harvest, withdrew to Panormo. Hasdrubal boldly advanced most of his army, including the elephants, towards the city walls. The Roman commander Lucius Caecilius Metellus sent skirmishers to harass the Carthaginians, keeping them constantly supplied with javelins which they obtained from the city's supplies. The ground was covered with excavations, made during the Roman siege, which made it difficult for the elephants to advance. Wounded by javelins and unable to defend themselves, the elephants fled through the Carthaginian infantry. Metellus timely moved a large force to the left flank of the Carthaginians, and charged their disorderly opponents, causing them to flee; Metellus captured ten elephants, but did not allow the enemy to be pursued. Contemporary accounts report no losses for either side, and later claims of between twenty thousand and thirty thousand Carthaginian casualties are considered unlikely by modern historians.

Builded by their victory at Panormo, a large army commanded by the consuls of the year, Publius Claudius Pulcher and Lucius Junius Pulo, moved against Lilibea, the main Carthaginian base in Sicily, and besieged the city, as well as his fleet of 200 newly rebuilt ships blockaded the port. At the beginning of the blockade, fifty Carthaginian quinqueremes assembled off the Aegadian islands, which lie 15–40 km west of Sicily. Once there was a strong westerly wind, they sailed towards Lilibea before the Romans could react and landed reinforcements and a large amount of supplies, and because they came out at night, they were able to evade them and rescue the Carthaginian cavalry. The Romans sealed the land access to Lilibea with camps and walls of earth and wood, although they also made repeated attempts to block the entrance to the port with a strong wooden barricade, due to the prevailing sea conditions they were unsuccessful. kept supplied by blockade runners, light and maneuverable quinqueremes with highly trained crews and experienced pilots.

Pulcher decided to attack the Carthaginian fleet, which was in the port of the nearby city of Drépano —present-day Trapani—, they set sail at night to carry out a surprise attack, but they dispersed in the dark. The Carthaginian commander Aderbal was able to get his fleet to sea before they were trapped and counterattacked at the Battle of Drepano. The Romans got bogged down against the shore and, after a hard day's fighting, were largely defeated by the more maneuverable Carthaginian ships with their better-trained crews, and consequently became the greatest naval victory of the war by part of Carthage. Carthage turned to the maritime offensive, causing it to inflict another heavy naval defeat at the Battle of Phintias and nearly wipe the Romans out of the sea. It would be seven years before Rome again attempted to field a fleet substantial, while Carthage put most of her ships in reserve to save money and free up manpower.

Conclusion

About 248 B.C. In BC, the Carthaginians held only two cities in Sicily: Lilibea and Drepano, which were well fortified and located on the western coast, where they could be supplied and reinforced without the Romans being able to use their superior army to interfere. When Hamilcar Barca He took command of the Carthaginians in Sicily in 247 BC. C. he only received a small army and the fleet gradually withdrew. Hostilities between Roman and Carthaginian forces were reduced to small-scale land operations, which suited Carthaginian strategy. Hamilcar employed combined arms tactics in a Fabian strategy from his base on Eryx, north of Drepano. This guerrilla warfare kept the Roman legions immobilized and preserved Carthage's foothold in Sicily.

After more than 20 years of war, both states were financially and demographically depleted. Evidence of Carthage's financial situation includes its request for a loan of 2,000 talents from Ptolemaic Egypt, although it was turned down. Rome it was also close to bankruptcy, and the number of adult male citizens, who provided the manpower for the navy and legions, had declined by 17 percent since the start of the war. Goldsworthy describes the manpower losses Romana as "dreadful".

At the end of 243 B.C. Realizing that they would not capture Drepano and Lilibea unless they could extend their blockade to the sea, the Roman Senate decided to build a new fleet. With the state coffers depleted, the Senate borrowed from the wealthiest citizens of Rome to finance the construction of one ship each, repayable with the reparations that would be imposed on Carthage once the war was won. The result was a fleet of approximately 200 quinqueremes, built, equipped, and manned at no government expense. The Romans modeled the ships of their new fleet after a captured blockade runner with especially good qualities. By now, the Romans they had experience in shipbuilding and, with a proven model ship, produced high-quality quinqueremes. Importantly, they abandoned the corvus, which improved the speed and handling of the ships, but it forced the Romans to change their tactics; they would have to be superior sailors, rather than superior soldiers, to defeat the Carthaginians.

The Carthaginians built a larger fleet which they intended to use to bring supplies to Sicily, then embarking much of the Carthaginian army stationed there to use as marines, but the intercepted a Roman fleet under Gaius Lutatius Catullus and Quintus Valerius Falton, and in the hard-fought Battle of the Aegadian Islands, the better-trained Romans defeated the undermanned and poorly trained Carthaginian fleet. After achieving this decisive victory, the Romans The Romans continued their land operations in Sicily against Lilybaeia and Drepano. The Carthaginian Senate was reluctant to allocate the necessary resources to build and man another fleet. Instead, it ordered Hamilcar to negotiate a peace treaty with the Romans, which he left behind. in the hands of his subordinate Gisco. They signed the Treaty of Lutacio (241 BC) and ended the First Punic War: Carthage evacuated Sicily, handed over all the prisoners taken during the war and paid an indemnity of 3,200 talents. for ten years.

Consequences

The war lasted twenty-three years: it was the longest in Romano-Greek history and the greatest naval contest in the ancient world. After its conclusion, Carthage tried to avoid paying what it owed to the foreign troops that had fought on its rows. They finally rebelled; they were joined by many disgruntled local groups. The rebellion was eventually put down, albeit with great difficulty and considerable savagery. In 237 B.C. C., Carthage prepared an expedition to recover the island of Sardinia, which had previously been lost to the newly defeated rebels. Cynically, the Romans declared that they considered this an act of war, so they added in their peace terms the cession of Sardinia and Corsica and the payment of additional compensation of one thousand two hundred talents. Weakened by thirty years of war, Carthage acquiesced to avoid further conflict with Rome; the additional payment and the resignation of Sardinia and Corsica were added to the treaty as a codicil. These actions by Rome fueled resentment in Carthage, which was not resigned to accepting the role assigned to it by Rome, and are considered contributing factors to the outbreak of the second punic war.

Hamilcar Barca's leading role in defeating mutinous foreign troops and African rebels greatly increased the prestige and power of the Bárcid family. In 237 B.C. C. Hamilcar led many of his veterans in an expedition to expand the Carthaginian possessions in southern Iberia —present-day Spain. The region became over the next twenty years a semi-autonomous fiefdom of the Barcids and was the source of much of the silver used to pay the large indemnity owed to Rome.

For Rome, the end of the First Punic War marked the beginning of its expansion beyond the Italian peninsula. Sicily was the first Roman province, whose government was entrusted to an ex-praetor; it would become important to Rome as a source of grain. Sardinia and Corsica, combined, also became a Roman province and a source of grain. It was ruled by a praetor who maintained large troops for at least the next seven years to subdue the islanders. Syracuse was granted nominal independence and ally status during the lifetime of Hiero II. Thereafter, Rome was the major military power in the western Mediterranean and, increasingly, in the Mediterranean region as a whole. The Romans had built over a thousand galleys during the war, and this experience of building, manning, training, supplying, and maintaining so many ships laid the foundations of Rome's maritime dominance for six hundred years. To this, the question of which state would control the western Mediterranean remained uncertain, and the Carthaginian siege in 218 BC. C. from the Levantine city of Sagunto, protected by the Romans, triggered the Second Punic War with Rome.