First crusade

The First Crusade began the complex historical phenomenon of military campaigns, armed pilgrimages and the establishment of Christian kingdoms, whose objective was to regain control of the lands lost to the Muslim advance. This prolonged hiatus from the Middle Ages convulsed the region between the XI and XIII and is known by historiography as the crusades.

The first military campaign, encouraged by Pope Alexander II, considered by some to be the first crusade (1063) or, at least, the most obvious antecedent of what the crusade was later.

Taking advantage of the call for help from the Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos, confronted with the Seljuk Turks, Pope Urban II preached in 1095 in the different Christian countries of Western Europe the conquest of the so-called Holy Land. The failed attempt by Peter the Hermit was followed by the mobilization of an organized army, inspired by the ideal of holy war and led by nobles mainly from the Kingdom of France and the Holy Roman Empire, which was nourished by its advance of knights, soldiers and a large population, until it became a phenomenon of massive migration. The crusaders penetrated the so-called Sultanate of Rüm and advancing towards the south, they seized various cities and rejected the forces sent against them by the governors divided in their internal disputes, until entering the territories of the Fatimid dynasty, they conquered the July 15, 1099 the city of Jerusalem, forming the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

The first crusade supposed politically the constitution of the Latin States of the East and the recovery for the Byzantine Empire of some territories, at the same time that it meant a turning point in the history of the relations between the societies of the Mediterranean area, marked by a period of expansion of the power of the western world and by the use of religious fervor for warfare. They also made it possible to increase the prestige of the papacy and the resurgence, after the fall of the Roman Empire, of international trade and the increase in exchanges that favored the economic and cultural revitalization of the medieval world.

Historical background

The origins of the crusades in general, especially the first crusade, stem from the earliest events of the Middle Ages. The consolidation of the feudal system in Western Europe after the fall of the Carolingian Empire, combined with the relative stability of the European borders after the Christianization of the Vikings and Magyars, had led to the birth of a new class of alpha warriors (the feudal cavalry) that they were in continuous internal struggles, provoked by the structural violence inherent in the economic, social and political system itself.

On the other hand, in the early 8th century century, the Umayyad caliphate had managed to conquer Egypt very quickly and Syria from the Christian Byzantine Empire, as well as North Africa. The conquests had extended to the Iberian Peninsula, ending the Visigothic kingdom. From the same century VIII this expansion was stopped in the West, with the battles of Covadonga (722) and Poitiers (732), and the establishment of the Christian kingdoms of the north of the peninsula and of the Carolingian Empire, in what represented the first efforts of the Christian leaders to capture territories lost to the Muslim rulers, and which would be expressed ideologically from the Asturian chronicle corpus. -Leonese in what was later called the Spanish Reconquest. From the XII century it had common factors with the Eastern crusades (papal bulls, military orders, presence of European crusaders).

The most visible trigger that contributed to the change in the Western attitude towards Muslims from the East occurred in the year 1009, when the Fatimid caliph al-Hakim bi-Amrillah ordered the destruction of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

Other Muslim kingdoms that emerged after the collapse of the Umayyads, such as the Aghlabid dynasty, had invaded Italy in the 9th century. The state that arose in that region, weakened by internal dynastic strife, became easy prey for the Normans who captured Sicily in 1091. Pisa, Genoa, and the Kingdom of Aragon began fighting Muslim kingdoms for control. of the Mediterranean Sea, examples of which we can find in the Mahdia campaign and in the battles that took place in Majorca and Sardinia.

The idea of holy war against Muslims finally caught on and was attractive to both the religious and secular powers of Europe's Middle Ages, as well as the general public. In part, this situation was favored by the military successes of the European kingdoms in the Mediterranean. At the same time, a new political concept emerged that encompassed Christianity as a whole, which meant the union of the different Christian kingdoms for the first time and under the spiritual guidance of the papacy and the creation of a Christian army to fight against the Muslims.. Many of the Islamic lands had previously been Christian, and especially those that had formed part of the Roman Empire both in the East and in the West: Syria, Egypt, the rest of North Africa, Hispania, Cyprus and Judea. Finally, the city of Jerusalem, along with the other lands that surrounded it, including the places where Christ had lived and died, were especially sacred to Christians.

In any case, it is important to clarify that the first crusade was not the first case of holy war between Christians and Muslims inspired by the papacy. Already during the papacy of Alexander II, he preached the war against the Muslim infidel on two occasions. The first occasion was during the war of the Normans in their conquest of Sicily, in 1061, and the second case was framed within the wars of the Spanish Reconquest, in the Crusade of Barbastro in 1064. In both cases the Pope offered the Indulgence Christians to participate.

In 1074, Pope Gregory VII called on the milites Christi ("soldiers of Christ") to come to the aid of the Byzantine Empire. He had suffered a heavy defeat at the Battle of Manzikert (1071) at the hands of the Seljuk Turks, which opened the gates of Anatolia to the Turks, who established several sultanates on the peninsula. The conquest of Anatolia had closed the land routes to pilgrims heading to Jerusalem. Their call, though largely ignored and even met with considerable opposition, along with the large number of pilgrims traveling to the Holy Land during the 11th century , served to focus much of the Western attention on events in the East. Some monks such as Peter of Amiens the Hermit or Walter the Indigent, who dedicated themselves to preaching Muslim abuses in front of pilgrims traveling to Jerusalem and other holy places in the East further fueled the fire of the Crusades.

Alexius Komnenos, who had previously employed Norman mercenaries and other Western countries, wrote a letter to Pope Urban II, requesting his support and sending new mercenaries to fight for Byzantium against the Turks.

Finally, it would be Urban II himself who spread the first idea of a crusade to capture the Holy Land among the public. After his famous speech at the Council of Clermont (1095), in which he preached the first crusade, the nobles and clergy present began to shout the famous words, Deus vult! (Latin for "! God wants it!").

Urban II's preaching caused an outburst of religious fervor both in the common people and in the small nobility (not so in the kings, who did not participate in this first expedition).

East at the end of the 11th century

To the east, Western Christendom's closest neighbor was Eastern Christendom: the Byzantine Empire, a Christian empire that since the Eastern Schism of 1054 had explicitly severed its ties with the pope of Rome, whose authority ceased to exist. recognized (in fact, it had never been accepted more than as that of a primum inter pares alongside the patriarchs). Subtle dogmatic differences (the Filioque clause and the Eucharist acimita or procimita) made it possible to define the opposition between the Western Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church. The latest military defeats of the Byzantine Empire against its neighbors had caused deep instability that would only be resolved with the rise to power of General Alexios I Komnenos as basileus (emperor). Under his reign, the empire was confined to Europe and the west coast of Anatolia and faced many enemies, with the Normans to the west and the Seljuks to the east. Further east, Anatolia, Syria, Palestine, and Egypt were under Muslim control, though to some extent culturally fragmented at the time of the First Crusade. This fact contributed to the success of this campaign.

Anatolia and Syria were under the rule of the Sunni Seljuks, who had once formed a large empire but were now divided into smaller states. Sultan Alp Arslan had defeated the Byzantine Empire at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, and had succeeded in incorporating much of Anatolia into the empire, however the empire split after his death the following year. Malik Shah I succeeded Alp Arslan and would continue to reign until 1092, when the Seljuk empire faced internal rebellion. In the Sultanate of Rüm, in Anatolia, Malik Shah I would be succeeded by Kilij Arslan I, and in Syria by his brother Tutush I, who died in 1095. The latter's sons, Radwan and Duqaq, inherited Aleppo and Damascus, respectively, further dividing Syria between different emirs facing each other and also facing Kerbogha, the atabeg of Mosul. All these states were more concerned with maintaining their own territories and controlling those of their neighbors than with cooperating among themselves to deal with the cross threat.

In other parts of what was nominally Seljuk territory, the Artuchid dynasty had also consolidated. In particular, this new dynasty ruled northwestern Syria and northern Mesopotamia, and also controlled Jerusalem until 1098. East of Anatolia and north of Syria a new state was founded, ruled by what would become known as the dynasty of the Danishmends for having been founded by a Seljuk mercenary known as Danishmend. The Crusaders did not come into any significant contact with these groups until after the Crusade. Finally, one must also take into account the Nizaris, who by then were beginning to have some relevance in Syrian affairs.

While the region of Palestine was under Persian rule and during the early Islamic era, Christian pilgrims were generally treated fairly. One of the earliest Islamic rulers, Caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab, allowed Christians to perform all their rituals except for any type of celebration in public. However, at the turn of the century XI, the Fatimid caliph al-Hakim bi-Amrillah began to persecute Christians in Palestine, a persecution that would lead, in 1009, to the destruction of the most sacred temple for they, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Later he softened the measures against the Christians and, instead of persecuting them, he created a tax for all the pilgrims of that confession who wanted to enter Jerusalem. However, the worst was yet to come: a group of Muslim Turks, the Seljuks, very powerful, aggressive and fundamentalist in terms of the interpretation and compliance with the precepts of Islam, began their rise to power. The Seljuks saw Christian pilgrims as contaminants of the faith, so they decided to put an end to them. At that time, barbaric stories began to emerge about the treatment of pilgrims, which were passed from mouth to mouth to Western Christianity. These stories, however, instead of deterring pilgrims, made the journey to the Holy Land take on a much more sacred aura than it had before.

Egypt and much of southern Palestine were under the control of the Fatimid Caliphate, of Arab origin and the Shiite branch of Islam. His empire had been significantly smaller since the arrival of the Seljuks, and Alexios I even advised the Crusaders to work together with the Fatimids to confront their common enemy, the Seljuks. At that time, the Fatimid Caliphate was ruled by Caliph al-Musta'li (although real power rested in the hands of the vizier al-Afdal Shahanshah), and after losing the city of Jerusalem to the Seljuks in 1076, the they had recovered from the Artuchids in 1098, when the Crusaders were already on the march. The Fatimids, at first, did not consider the crusaders as a threat, since they thought they had been sent by the Byzantines, and that they would be content with the capture of Syria, and leave Palestine alone. They did not send an army against the crusaders until they reached Jerusalem.

Convocation and beginning of the first crusade. The poor man's crusade

Council of Clermont

In March 1095, Alexios I Komnenos sent messengers to the Council of Piacenza to ask Pope Urban II for help against the Turks. The emperor's request met with a favorable response from Urban, who hoped to repair the Schism of East and West, which occurred forty years earlier, and to reunite the Church under the papacy as "chief bishop and prelate throughout the world" (according to his words in Clermont), by helping the Eastern churches in a time of need.

The Council of Piacenza, which allowed the establishment of papal authority in Italy in a period of crisis, was attended by some 3,000 clergy and approximately 30,000 laymen, as well as Byzantine ambassadors who implored all "Christendom's help against non-believers". Having secured his authority in Italy, the pope was free to concentrate on preparing for the crusade that the eastern ambassadors had requested. Urbano also knew that Italy was not going to be the land that "woke up to an explosion of religious enthusiasm" at the calls of a pope who, moreover, had a disputed title. His intentions to persuade "many to promise, by oath, to help the emperor as faithfully as possible and as far as they could against the pagans" did not reach many.

The invitation to a massive crusade against the Turks would arrive in the form of French and English embassies to the courts of the most important medieval kingdoms: France, England, the Holy Empire and Hungary, which could not have enlisted in the first crusades for the mourning that was observed after the death of King Saint Ladislaus I of Hungary (1046-1095), which would last for about three years. Pope Urban II eventually considered Ladislaus I as a suitable candidate to command the first crusade, since he the Hungarian king was widely known for his chivalrous bearing and his fights against the Cuman invaders; however, he died a few months before, while he was carrying out a military campaign against the kingdom of Bohemia in 1095.

The formal announcement would be at the Council of Clermont, which met in the heart of France on November 27, 1095; Pope Urban delivered an inspiring sermon in front of a large audience of French nobles and clergy. He appealed to his audience to wrest control of Jerusalem from the hands of the Muslims and, to emphasize his appeal, he explained that France was overpopulated, and that the land of Canaan was at their disposal overflowing with milk and of honey. He spoke of the problems of violence among nobles and that the solution was to turn to offer the sword in the service of God: "Make thieves knights". He spoke of both earthly and spiritual rewards, offering forgiveness from sins to all those who died in the divine mission. Urbano made this promise invested with the spiritual legitimacy that his papal office gave him, and the crowd let themselves be carried away in religious frenzy and enthusiasm for the mission, interrupting his speech with shouts of Deus vult! ("God wills it!") which was to become the motto of the first crusade.

Urban's sermon is among the most important speeches in European history. There are five versions of his speech in different writings, but it is difficult to know exactly his true words, since all those writings come from times when Jerusalem had already been captured. For this reason, it is not possible to clearly distinguish between the true events and those that were recreated in light of the successful outcome of the crusade. In any case, what is clear is that the response to the speech was much broader than expected. During the years 1095 and 1096, Urban spread the message throughout France, while urging his bishops and legates to spread his words to every other corner of France, as well as Germany and Italy. Urban tried to forbid certain people (including women, monks, and the sick) from joining the crusade, but he found this impossible.

To understand the success of the summons to the first crusade, one must also take into account the situation in which the members of the European nobility found themselves at that time. Their lifestyle, continually making war against each other, and confronting more or less habitually with various ecclesiastical institutions (with which, on the other hand, they were closely linked, given the common privileged condition of both estates and the family identity between high clergy and nobility), posed a very serious spiritual threat to them, since they all saw themselves, to a greater or lesser extent, involved in behaviors that the Church described as sins punishable by the eternal punishment of hell, and which sometimes entailed the most immediate and visible earthly punishment. of excommunication, equivalent to civil death. The crusade meant for them a way of salvation through an activity that they knew and mastered: war. In this sense, the historian Pierre Tucoo-Chala writes the following:

That some lords have had the thought of at the same time ensuring salvation in the beyond and obtaining in these distant lands a luck more enviable than they had before leaving is evidence. It was certainly not the case of the Viscount of Bearn. (...) It is likely that your deep faith has been comforted by the occasion that was finally presented for the first time to the thousand (caballeros) to put his lifestyle at the service of his religious convictions.(...) The ecclesiastics had no strong enough words to condemn the life practiced by these warriors. For them thousand, militia, implied malitia(...)

In the middle of the 15th century, the powerful (powerful) have become owners of castles specializing in the fight on horseback and seek to secure the necessary income to devote themselves only to the art of war. To do this, they oppress their peasants and cover the property of the clergy, which denounces their uncontrolled violence. To try to limit it, the Church had developed the Peace of God and then the Truce of God. (...) Despite these initiatives the clergy still manifested a great distrust towards their lifestyle.Pierre Tucoo-Chala

In the end, most of those who answered his call were not knights, but peasants with no wealth and little military training. On the other hand, it was in this audience that a message that not only offered redemption from their sins, but also provided them with a way to escape a life full of privations, in what would end up being an explosion of faith that was not easily manageable for the aristocracy.

As a result of this explosion of faith, many abandoned their possessions and set out for the East. To the nobles, the Church promised that their property would be respected until their return, although, in order to arm an army, many of the powerful crusaders (so called because of the cross that was woven into their garments) actually had to liquidate their property and prepare for a journey of no return. Many humble people, on the other hand, just set out, taking their families and all their meager possessions with them. These were the first to leave.

The Crusade of the Poor

The summons

Simultaneously with Urban II, several preachers, including Peter the Hermit, managed to inflame a large crowd of humble people, "among them peasants and artisans, as well as serfs" who, although Pope Urban had planned the departure of the crusade for August 15, 1096 coinciding with the festivity of the Assumption of Mary, it was launched before said date forming a disorganized and poorly supplied army made up of peasants and small nobles, under the direction of Pedro the Hermit, with the intention of conquering Jerusalem on his own.

Led by the preachers, the response of the population exceeded all expectations: although Urban had counted on the adherence to the crusade of a few thousand knights, he found a true migration of about forty thousand crusaders, although said numbers were made up for the most part of inexperienced soldiers, women and children.

The passage through the Kingdom of Hungary

Without any kind of military discipline, and when they found themselves in what to the crusaders probably seemed like a strange land (Eastern Europe), they soon found themselves in trouble, still in Christian territory. The main problem was that of supplies, as well as a large number of unscrupulous people who saw in the crusade an opportunity to plunder other territories. In this way, the Crusader armies committed numerous robberies and massacres in mid-1096 when they entered the Kingdom of Hungary.

Firstly, in March 1096, the French knights of Valter Gauthier entered, who lashed the Zimony region, and were quickly repelled by the forces of King Coloman of Hungary (nephew of the late Saint Ladislaus I of Hungary, who had accepted the call to the crusades before he died in June 1095). Hungary mourned Saint Ladislaus for three years; this, in addition to the weak initial position of the newly crowned King Coloman, was what prevented the Hungarian kingdom from joining the first crusades (it was in the fifth crusade that Andrew II of Hungary would lead the largest army in the history of the crusaders). After the ravages of Gauthier's French knights, the army of Pedro de Amiens would enter, which would be escorted through the kingdom by Coloman's Hungarian forces. However, after the crusaders from Amiens attacked the escorting soldiers and killed nearly 4,000 Hungarians, King Coloman maintained a hostile position against the crusaders crossing the kingdom towards Constantinople.

On the other hand, considering the situation, the Hungarian king Coloman allowed entry to the crusader armies of Volkmar and Gottschalk, whom he eventually also had to face and defeat near Nitra and Zimony, since just like the other previous groups they wreaked untold havoc and murder in Hungary. Next, the Hungarians stopped the forces of Count Emiko near the city of Mosony, and shortly after, the Hungarian king forced Godfrey of Bouillón to sign a treaty in the abbey of Pannonhalma, where the crusaders agreed to pass through the territory. Hungarian with a good behavior. After this, the forces left the Hungarian territories escorted by the armies of Coloman and continued towards Constantinople.

Arrival in Asia Minor

On the difficult journey some 10,000 people died, about a quarter of Peter's initial troops, although the rest reached Constantinople in August in relatively good condition. Once there, tensions arose again due to cultural and religious differences and a reluctance to distribute provisions among such a large number of people. To further complicate matters, Peter's followers joined other crusaders from France and Italy. Finally, the emperor Alexios Komnenos decided to quickly embark the thirty thousand crusaders to cross the Bosphorus, getting rid of that problem as soon as possible.

After crossing into Asia Minor, the crusaders began to argue among themselves and the army split into two separate parties. From there, the crowd plunged deep into Turkish territory, scoring an initial victory, but completely neglecting the rear. The military experience of the Turks was too much for the inexperienced Crusader army, with no practical knowledge of the art of war. Eventually, they were easily massacred and enslaved shortly after entering Seljuk territory. Peter the Hermit managed to return to Byzantium and join the princes' crusade. Another army of Bohemians and Saxons failed to break through Hungary before disbanding.

Persecution of the Jews

The First Crusade was the spark that started a tradition of organized violence against the Jewish people in Europe. Although antisemitism had existed in Europe for centuries, the first crusade marked the first instance of mass and organized violence against Jewish communities. In Germany, certain leaders interpreted that this fight against the infidel should be carried out not only against the Muslims located in the Holy Land, but also against the Jews who lived in their own lands.

The sermons preaching the crusade inspired even greater anti-Semitism. According to some preachers, Jews and Muslims were enemies of Christ, and it was the duty of Christianity to deal with these enemies or convert them to the Christian faith. The general public understood that the "confrontation" referred to by the preachers was synonymous with fighting to the death or killing them. The Christian conquest of Jerusalem and the establishment of a Christian empire would supposedly instigate the "End Times," during which the Jews were supposed to convert to Christianity. On the other hand, in some places in France and Germany the Jews were considered guilty of the crucifixion of Jesus, and they were a much more visible and close group than the Muslims. Many people wondered why they had to travel thousands of kilometers to fight the infidels if there were already non-believers close to their homes.

Setting out in the early summer of 1096, a German army of some ten thousand crusaders and led by the nobles Gottschalk, Volkmar, and Emicho headed north along the Rhine, away from Jerusalem, to begin a series of pogroms that some historians have come to call "the first holocaust".

The crusaders traveled north through the Rhine Valley in search of the Jewish communities better known as Cologne, before heading south. Jewish communities were given the choice to convert or be massacred. Many refused to convert, and as news of the massacres spread, there were some cases of mass suicide.

This interpretation of the crusade as a war against all kinds of infidels, however, was not universal, and there is evidence that Jews found refuge in some Christian sanctuaries. One such case was that of the Archbishop of Cologne, who strove to protect the city's Jews from the massacre carried out by the population itself. In any event, thousands of Jews were murdered despite attempts by some ecclesiastical and secular authorities to protect them.

All these massacres were justified through the argument that Pope Urban's speeches had promised divine reward to those who killed infidels, no matter what kind of non-Christians they were. In that sense, the appeal was not addressed exclusively to the holy war against Muslims. Although the papacy abhorred and preached against these local actions against Jews and Muslims, these acts were repeated in all subsequent Crusader movements.

The First Crusade

Crusade of the Barons

The failure of the crusade of the poor would only be the preamble to what is usually identified as the first crusade, which is also known as the crusade of the barons or crusade of the princes. Much more organized than the previous one, the barons' crusade was made up of members of the feudal nobility and they were divided into four main groups according to their origin that used different routes to reach Constantinople.

- The first group, composed of gentlemen of Lorenese and Flemish origin, was commanded by Godofredo of Bouillón along with his brothers Balduino and Eustaquio and went to Constantinople through Germany and Hungary.

- The second group was composed of northern Norman knights commanded by Hugo de Vermandois, brother of King Philip I of France and who carried the papal standard, Stephen II of Blois, brother of King William II of England, Count Roberto II of Flanders and Robert II of Normandy and went to Constantinople by sea from Bari.

- The third group was composed by the southern Norman knights on whose front was Bohemundo de Tarento along with his nephew Tancredo who, after meeting with the northern Normans, left for Constantinople.

- The fourth group was composed of western knights led by Raimundo de Tolosa and accompanied by Ademar de Le Puy, pontifical legacy and spiritual leader of the expedition. This contingent went to Constantinople through Slovenia and Dalmatia.

In total, the Crusader army numbered between thirty and thirty-five thousand Crusaders, including about five thousand cavalry. Raymond of Toulouse was the leader of the largest contingent, made up of about eight thousand five hundred infantry and twelve hundred cavalry.

March on Jerusalem

After the successful convocation of the pope and the avalanche of participants, it was not possible to propose a unitary expedition, so different expeditions left Europe that would come together by different routes in Constantinople between November 1096 and May 1097. Accompanying Among the Christian knights there were many poor men (pauperes) who could only afford to buy the most basic clothes and, perhaps, some old weapons. Peter the Hermit, who had joined the princes' crusade in Constantinople, was held responsible for caring for these people, who were allowed to organize themselves into small groups, possibly like-minded military companies, often led by some impoverished gentleman.

The various groups of crusaders arrived in Constantinople with few provisions, hoping to receive help from Alexios I. Alexios, for his part, found himself in a difficult situation. After the dubious experience lived with the previous crusade of the poor, and taking into account that the Norman Bohemond of Taranto was an old enemy of his, he did not know to what extent he could trust the alleged Christian allies from the West. On the other hand, Alexios still had hopes of getting control of this group of crusaders, and it seems that he even contemplated the possibility of using them as agents of the Byzantine Empire to recover lost lands. Given the situation, Alexios reached an agreement with the Crusaders: in exchange for food and supplies, Alexios demanded that the Crusaders swear allegiance to him, and that they promise to return to the Byzantine Empire all the land they recovered from the Turks. The crusaders, without food or water, had no choice but to agree to take the oath, though not before a series of commitments had been made by all parties, and after military conflict had nearly broken out in the city itself in combat. open with the akritai of the emperor.

Only Prince Raymond evaded the oath, offering Alexios to lead the crusade himself. Alejo rejected the offer, although the two characters became allies due to the mistrust they both had in Bohemond.

Alexius reached an agreement with the Crusaders to send a military contingent under the command of General Tatikios (of Turkish origin, curiously) to accompany the Crusaders throughout Asia Minor. His first target would be Nicaea, a former city of the Byzantine Empire that was now the capital of the Sultanate of Rüm, ruled at the time by Kilij Arslan I. At the time, Arslan was engaged in a military campaign against the Danishmends in central Anatolia, and he had left both his treasure and his family behind, underestimating the military capabilities of the Crusaders. The city suffered a long siege that had little to no avail, as the Crusaders were unable to blockade the lake on which the city stood., and through this he could receive provisions. When Kilij Arslan received news of the siege he hastened back to his capital, and attacked the Crusader army on May 23 of that year. However, this time the Turks were defeated, although both sides suffered heavy losses, Seeing that he would not be able to liberate the city, he advised the garrison to surrender if the situation became untenable. Alejos, fearing that the crusaders would sack the city and destroy its wealth, made a secret surrender agreement with the city, and prepared to take it by night. On June 19, 1097, the Crusaders awoke to notice Byzantine banners flying from the city walls.

Not only were they forbidden to sack the city, but the crusaders were forbidden to enter the city except in small groups, which caused great unrest in the crusader army, and added to the already existing tension between Christians eastern and western. Finally, the crusaders set off in the direction of Jerusalem. Stephen of Blois wrote to his wife, Adela, estimating a journey of five more weeks to reach the holy city. In fact, that journey would take them two years.

The Crusaders, still accompanied by some Byzantine troops commanded by Tatikios, marched towards Dorilea, where Bohemond suffered a surprise attack from Kilij Arslan, in the Battle of Dorilea; On July 1 of that year, Godfrey was able to break through the enemy lines and, with the help of legate Ademar's troops (who attacked the Turks from the rear) defeated the Turks and sacked their camp. Kilij Arslan fought in retreat, and the Crusaders marched almost unopposed across Asia Minor as far as Antioch, save for a battle in September in which they also defeated the Turks. Along the way, the Crusaders were able to capture several cities, including Sozopolis, Konya, and Kayseri, though most of these cities were lost to the Turks again in 1101.

Overall, the march across Asia was very difficult for the Crusader army. It was midsummer, and the Crusaders had very little water and food, so many men and animals died on the march. As in Europe, Christians in Asia sometimes gave them food or money, but more often than not, the Crusaders looted and plundered if the opportunity presented itself. For their part, the different leaders of the crusade continued to dispute the absolute leadership of it, although none was powerful enough to take command, although Ademar de Le Puy was always recognized as a spiritual leader. After crossing the Cilician Gates, Baldwin separated from the rest of the crusaders, and headed towards the Armenian lands around the Euphrates. He arrived in the city of Edessa (today Urfa, in Turkey), which was in the hands of Armenian Christians, and was adopted as heir by King Thoros of Edessa, an Armenian belonging to the Orthodox Church of Greece and not in favor of their subjects because of their religion. Thoros was assassinated, and Baldwin became the new ruler, creating the County of Edessa, which in turn would be the first of the Crusader states.

Siege of Antioch

The Crusader army, meanwhile, marched towards Antioch, a city located halfway between Constantinople and Jerusalem and also of great religious value for Christianity. On October 20, 1097, the Crusaders besieged the city, beginning a siege that would last almost eight months. During this time, the Christians had to undergo terrible hardships, and were forced to face two major armies supporting the Crusaders. besieged sent by Damascus and Aleppo. Antioch was such a large city that the Crusaders did not have enough troops to completely encircle it, so they were able to maintain a certain level of supplies throughout that time. On the other hand, as the siege lengthened, it became increasingly clear that Bohemond intended to conquer the city in order to remain as governor.

Yaghi-Siyan, the governor of Antioch, could only count on his own personal army to defend himself. To prepare for the siege, he exiled many of the Christians belonging to the Greek and Armenian Orthodox Church, whom he considered unreliable. He also imprisoned Juan de Oxite, patriarch of Antioch of the Greek Orthodox Church, and turned St. Peter's Cathedral into a stable. The Syrian Orthodox Christians were generally respected, since Yaghi-Siyan considered them more loyal to him than the others since they were also enemies of the Greeks and the Armenians. Yaghi-Siyan and his son Shams ad-Dawla requested help from Duqaq (governor of Damascus). Meanwhile he was launching attacks on the Christian camp and harassing the foraging parties of the invading army.

Yaghi-Siyan knew from his informants that there were divisions among the Christians because both Raymond IV of Toulouse and Bohemond of Taranto wanted the city for themselves. On one occasion, while Bohemond was searching for food, Raymond attacked the city alone, but was repelled by Yaghi-Siyan's troops. On December 30, the expected reinforcements from Duqaq arrived, but were defeated by Bohemond's supply party, so they withdrew to Homs.

Yaghi-Siyan then went to Radwan (governor of Aleppo) for help. However, in February of that year, the army sent by Radwan was also defeated and Yaghi-Siyan took advantage of the invading army's temporary march to make a sortie against his camp, but he too had to withdraw when the crusaders returned victorious. In March, Yaghi-Siyan managed to ambush a party of crusaders bringing wood and other materials from the port of San Simeon. News reached the Crusader camp that Raymond and Bohemond had died in that battle, and there was great confusion that Yaghi-Siyan took advantage of to attack the army commanded by Godfrey of Bouillon. However, Yaghi-Siyan was again repelled when Bohemond and Raymond returned to camp.

This time the governor went to Kerbogha, atabeg of Mosul, for help. The crusaders knew they had to take the city before Kerbogha's reinforcements arrived, and Bohemond secretly negotiated with one of Yaghi-Siyan's guards, an Armenian named Firuz, who agreed to betray the city. On June 2, 1098, the Crusaders entered the city, killing almost all of its inhabitants before Kerbogha could come to their aid. The garrison withdrew into the citadel. Only a few days later the Muslim army of 200,000 fighters arrived, which began a new siege, this time with the Christians (only about 20,000 people including non-combatants) inside the city. Just then, a monk named Pedro Bartolomé claimed to have discovered the Holy Lance in the city and, although some were skeptical about the finding, the event was considered a miracle that foreshadowed victory over the infidels.

On June 28, the Crusaders defeated Kerbogha in a pitched battle, a victory partly attributed to the fact that Kerbogha was unable to organize the various factions that made up his army. As the Crusaders marched against the Muslims, the Fatimid section deserted the Turkish contingent, fearing that Kerbogha would become too powerful if he defeated the Crusaders. On the other hand, and according to the Christian legend associated with the discovery of the Holy Lance, an army of Christian saints would have come to the aid of the crusaders in battle, tearing Kerbogha's army to pieces.

Bohemond of Taranto, after the withdrawal of the Byzantine armies that had accompanied them on the expedition, alleged desertion on their part, and argued that said desertion invalidated all the oaths they had taken against Alexios I. Bohemond, thanks to the breaking of the oath, he retained the city for himself, although not all the crusaders agreed, and especially Raymond of Toulouse. The discussions between the leaders meant a new delay in the march of the crusade, which remained stagnant throughout the rest of the year. On the other hand, the taking of Antioch implied the birth of the second Crusader State.

Meanwhile, an outbreak of a plague (possibly typhus) broke out on the scene, killing many of the crusaders, including the papal legate Ademar de Le Puy. The soldiers had fewer and fewer horses, and the Muslim peasants refused to provide them with food. In December of that year, the city of Ma'arrat al-Numan was captured after a siege in which, in addition to ending with the murder of the entire population, there were cases of cannibalism among the crusaders.

The lesser knights grew impatient, threatening to continue on to Jerusalem, leaving their leaders and their infighting behind. Finally, early in 1099, the march on the Holy City was renewed, leaving Bohemond behind as the new prince of Antioch.

Siege and conquest of Jerusalem

From Antioch the crusaders marched on Jerusalem. The city at that time was disputed between the Fatimids of Egypt and the Turks of Syria. Along the way, they conquered several Arab places (including the future Krak des Chevaliers castle, which was abandoned), and signed agreements with others, eager to maintain their independence and make it easier for the Crusaders to attack the Turks. As they headed south along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea, the crusaders did not encounter much resistance, as the local leaders preferred to make peace agreements with them and supply them without escalating to armed conflict.

Jerusalem, meanwhile, had changed hands several times, in recent times and since 1098 had been in the hands of the Fatimids of Egypt. The Crusaders arrived before the city walls in June 1099 and, just as they did Antioch, deployed their troops to subject it to a long siege, during which the Crusaders also suffered heavy casualties due to lack of security. food and water around Jerusalem. By the time the Crusader army reached Jerusalem, only 12,000 men remained of the initial army, including 1,500 cavalrymen. Faced with what seemed like an impossible task, the Crusaders carried out several attacks against the city walls, but all were repelled. Accounts from the time indicate that the morale of the army was improved when a priest named Pedro Desiderio claimed to have had a divine vision in which he was instructed to march barefoot in procession around the city walls, after which the The city would fall in nine days, following the Biblical example of the fall of Jericho. On July 8, the Crusaders held that procession.

The city would finally fall into Christian hands on July 15, 1099, thanks to unexpected help. Genoese troops led by Guillermo Embriaco had headed for the Holy Land on a private expedition. They were going first to Ashkelon, but were forced by a Fatimid army from Egypt to march inland towards Jerusalem, a city that was then besieged by the Crusaders. The Genoese had previously dismantled the ships in which they had sailed to the Holy Land, and used that wood to build siege towers. These towers were sent towards the city walls on the night of July 14 to the surprise and concern of the defending garrison. On the morning of the 15th, Godfrey's tower reached its section of the walls near the northeast corner of the city and, according to the Gesta, two knights from Tournai named Letaldo and Engelberto were the first to access the city, followed by Godofredo, his brother Eustaquio, Tancredo and his men. Raymond's tower was blocked by a ditch, but since the Crusaders had already entered the other way, the guards surrendered to Raymond.

Throughout that same afternoon, night and morning of the following day, the crusaders unleashed a terrible slaughter of men, women and children, Muslims, Jews and even the few Eastern Christians who had remained in the city. Although many Muslims sought refuge in the Al-Aqsa Mosque and Jews in their synagogues near the Wailing Wall, few crusaders took pity on the lives of the inhabitants. According to the anonymous work Gesta Francorum, "... the carnage was so great that our men walked with blood up to their ankles..." Other stories that speak of blood reaching the height of the reins of the horses are reminiscent of passages from the Apocalypse (14:20).

Two thousand Jews were locked in the main synagogue, which was set on fire. One of the men who participated in that butchery, Raymond of Aguilers, canon of Puy, left a description for posterity that speaks for itself:

Wonderful shows cheered our sight. Some of us, the most pious, cut off the heads of the Muslims; others made them targets of their arrows; others went further and dragged them to the bonfires. In the streets and squares of Jerusalem there were only a lot of heads, hands and feet. So much blood was poured out in the mosque built on the temple of Solomon that the bodies floated in it and in many places the blood reached us to the knee. When there were no more Muslims to kill, the army chiefs went to the church of the Holy Sepulchre for the thanksgiving ceremony.

Tancredo, for his part, claimed control of the Jerusalem temple and offered protection to some of the Muslims who had taken refuge there with the help of Sigismund Gozzer, a Tridentine in charge of the Lombard crusade. However, they were unable to prevent his death at the hands of his fellow crusaders.

Actually, if you'd been there, you'd have seen our feet colored to the ankles with the blood of the massacre. But what else can I tell you? None were left alive; there was no mercy on women or children.Fulquerio de Chartres.

Some crusader chiefs, such as Gastón de Béarn, tried to protect the civilians sheltering in the Temple by giving them their banners, but to no avail, because the next day a group of exalted knights murdered them too. Only a part of the garrison was saved, protected by the oath of Raymond of Toulouse.

On the other hand, the Gesta Francorum establishes that some people managed to escape the capture of Jerusalem alive. Its author wrote: "When the heathen had been defeated, our men captured many, both women and men, and either put them to death or held them captive." they were sent out of the city because of the stench, since the whole city was full of corpses; and therefore the living Saracens dragged the dead to the exits of the walls and placed them on pyres, as if they were houses. No one ever saw or heard of such a massacre of heathens, for the funeral pyres stood like pyramids, and no one knows their number except God himself."

End of the crusade

First, the Crusaders offered Raymond of Toulouse the title of King of Jerusalem, but he declined. It was then offered to Godfrey of Bouillon, who agreed to rule the city, but refused to be crowned king, saying he would not wear a "crown of gold" in the place where Christ had worn "a crown of thorns". instead, he took the title of Advocatus Sancti Sepulchri ("protector of the Holy Sepulchre") or, simply, that of "prince". In the last action of the crusade he led an army that defeated an invading Fatimid army at the Battle of Ashkelon. Godfrey died in July 1100 and was succeeded by his brother, then Baldwin of Edessa, who would accept the title of King of Jerusalem and would be crowned under the name of Baldwin I of Jerusalem.

With this conquest the first crusade ended, the only one that was successful. After the capture of Jerusalem, many Crusaders returned to their places of origin, although others stayed to defend the newly conquered lands. Among them, Raymond of Tolosa, upset at not being the king of Jerusalem, became independent and headed for Tripoli (in present-day Lebanon), where he founded the county of the same name.

The expeditions of 1101 and the establishment of a new kingdom

Having captured Jerusalem and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the crusading oath had been fulfilled. However, there were many knights who had returned home before reaching Jerusalem, as well as many others who had not made it to Europe. When news of the crusade's success arrived, these men were ridiculed by their families and threatened with excommunication by the clergy. On the other hand, many other crusaders who had remained in the crusade until its end also returned to their homes, so that, according to Fulcherio de Chartres, in the year 1100 there were only a few hundred knights left in the new kingdom.

The news of the recapture of Jerusalem had spread like wildfire in Europe and crowds of people wanted to make a pilgrimage where Jesus Christ had died. Well, in the fall of 1100, a multitude of monks, workers, artisans, women, children, as well as criminals set out on a pilgrimage to the holy land (at least that was the initial idea) from Lombardy under the command of Archbishop Anselmo of Milan. When this peculiar retinue arrived in Constantinople early in the year 1101, the Emperor courteously received it and arranged for it to be transported by sea to Anatolia. The Lombards reluctantly accepted Raymond IV of Toulouse as head of the expedition who happened to be at the emperor's court discussing further conquests for Christianity, although there were some who accused him of following the emperor's orders. The expedition arrived at Nicomedia, when they settled and later continued their advance they were accompanied by some troops under the command of the Duke of Normandy Esteban de Blois.

Later, a meeting was called where they would really decide what direction the expedition would take. There were some who wanted to follow a direct route to Jerusalem while avoiding the enemy forces as much as possible. Which, taking into account the category of the members, seemed the most prudent in addition to being the original plan. However, the contingent decided to go to free Bohemond, prince of Antioch who was a prisoner in northern Anatolia. Near the city of Amasya, the expedition faced a contingent of Turkish clans, which resulted in the defeat of the Christians. Some people managed to escape, but most died or were captured and later enslaved. Most of Raymond of Tolosa's entourage managed to flee and take refuge in Constantinople. After this unfortunate event for the Christians, the crusaders accused the emperor of conspiring together with the Turks for the defeat suffered, without evidence, on the other hand, the emperor of Byzantium did not take this news well, as a consequence of the diplomatic relations between the West and Constantinople deteriorated further.

Participants in the First Crusade

Armed pilgrimage

Although it is called the first crusade, none of those who participated in it actually saw themselves as a "crusader," which is a term coined after the fact. The reference to the Crusaders appeared in the early 13th century, more than 100 years after the First Crusade. Nor did the crusaders see themselves as the first, since they did not know that there would be crusades after their own. In reality, they saw themselves as mere pilgrims (peregrinatores) on a journey (iter), with the particularity that they were armed, and it is in this condition, that of participants in an armed pilgrimage, referred to in contemporary accounts.

Pilgrimage participants were required to swear an oath before the Church to complete the journey, and faced excommunication if they failed, giving the crusade official status. Crusaders were required to swear that their journey would not be complete until they had set foot inside the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem. On the other hand, and since the pilgrimages were events open to anyone who wanted to participate in them, not entirely desirable candidates for a military expedition could also join. Women, old and sick, despite the fact that they were discouraged from participating, could join without anyone being able to forbid them.

Popularity of the crusade

The first crusade attracted the greatest number of peasants, which meant that what began as a minor call for military assistance turned into a major population migration. The call to go to the crusade was very popular, among other things, because it was able to merge the figures of the medieval warrior and the pilgrim into one. Like a holy warrior in a holy war, the participant in the crusade carried his weapon to fight for the Church, obtaining in return all the spiritual benefits such as indulgence or martyrdom if the participant died in battle.

Like a pilgrim on his pilgrimage, a crusader would have the right to receive hospitality and personal protection from the Church, protection that included both person and property. The benefits of the indulgence had a double source, both participating as holy warriors of the Church and pilgrims, so it would be granted to them whether they died in battle or survived the crusade. On the other hand, it was not an indulgence in the medieval sense, since the indulgences of that time were the object of sale, but rather it was based more on a system of voluntary self-imposed penance to achieve absolution. This crucial difference is what separates the medieval indulgence from the original idea of the crusade.

Finally, there were participants who were forced by their feudal lord. The poorer classes looked to the local nobility for guidance, and that made it so that a powerful enough aristocrat could motivate others to join the cause as well. The connection with a wealthy leader allowed the average peasant to be able to contribute to the crusade under a certain protection on the trip, unlike those who came at his expense. There were also family obligations, which caused some soldiers to come to support a relative who had also sworn to participate in the crusade. All of these factors motivated different people for different reasons to join the crusade.

Some nobles, such as certain kings and some of their heirs, were prohibited from participating because of their dynastic position.

Spiritual and Earthly Rewards

The call for the crusade came at a time when, after a series of years of good harvests, the population of Western Europe had increased, thereby increasing the size of Christendom's armies. This allowed to assume a series of campaigns such as the Reconquest and the Crusade. In addition, the lure of starting a new life in a richer and more prosperous Orient encouraged many people to leave their lands. Population expansion meant diminishing opportunities for enrichment in Europe, and the potential spiritual, political, and financial rewards of the crusade tempted many participants.

The traditional view of the crusaders' motives for participating in the expedition explains that most of the participants were young sons of nobles who had no possibility of inheriting land due to the practice of primogeniture and primogeniture, and dispossessed nobles who They left in search of a new life in the rich Orient. Rumors about treasures discovered in Muslim lands in Al-Andalus were very attractive, and made people consider that if there were such treasures in Spain, there should be many more in Jerusalem. In any case, and while these reasons were real to a certain extent, they were not the only motivation for most. On the contrary, more recent scholarship suggests that although Pope Urban promised the crusaders both spiritual and material gains, the crusaders' primary goal was more spiritual than material.

In that sense, the studies carried out by Jonathan Riley-Smith show that the crusade was an immensely expensive campaign, one that was only within the reach of those knights who already had considerable wealth, such as Hugh I of Vermandois or Robert II of Normandy, who were related to the French and English royal families, or Raymond IV of Toulouse, who ruled much of southern France. Even in these cases, these knights had to sell much of their land to relatives or the Church before they could participate in the crusade, and their relatives also often had to contribute part of the money necessary for the campaign. Riley-Smith therefore claims that there is no actual evidence to support the assumption that the crusade was an opportunity for young sons to seek wealth that would, in turn, make them no longer a burden on their families.

As an example of spiritual motivation above the earthly, Godofredo de Bouillon and his brother Balduino settled a series of disputes with the Church, bequeathing their land to the local clergy. The documents that record these transactions were written by the clerics, and not by the knights, and seem to idealize these nobles and present them as pious men who only sought to fulfill a pilgrimage vow.

On the other hand, poorer knights (minores) could only consider going on the crusade if they hoped to survive on alms, or if they were able to enter the service of a wealthy nobleman. This last case was, for example, that of Tancredo de Galilea, who agreed to serve under the orders of his uncle Bohemond. Later crusades would be organized by kings or emperors, and would be financed by special taxes.

Later events

The outcome of the First Crusade had a major impact on the history of the two warring sides. The newfound stability in the west created a warrior aristocracy in search of new conquests and heritage, and the prosperity of major cities meant the economic capacity to equip expeditions. The Italian maritime city states, in particular Venice and Genoa, were also interested in expanding trade. For its part, the papacy saw the crusades as its way of imposing Catholic influence as a unifying force, turning warfare into a religious mission. This meant a new attitude towards religion that made it possible for religious discipline, previously applicable only to monks, to also extend to the battlefield, with the creation of the concept of the religious warrior and the feeling of chivalry.

Although unlikely, alliances between Muslims and Christians in the early years of the first crusade were common, as when in 1107 the city of Aleppo, which was Muslim, defeated, in cooperation with Christian Antioch, the armies of neighboring Muslim and Christian Mosul and Edessa respectively, the latter ruled by Baldwin I of Jerusalem. These alliances prove -at least at first- the multicultural relationship that both peoples had, moved by their own interests in the area.

Changes occurred in the region that in many cases did not sit well with the local population, accustomed to a treatment that, although Muslims were indifferent, their freedom of worship was respected, as long as they paid a special tribute called the jizyah, which people who did not believe in Allah such as Jews or Christians were charged. Contrary to the now Christian Roman government, it imposed itself with force on the contours, demanding an almost total submission to the Roman Catholic command now imposed, of course this generated non-conformity for not only Jewish and Muslim communities but also for non-Catholic Christian communities such as the Orthodox Church Greek, Coptic Church and adherents attached to the Syriac Orthodox Church who were even located in the region before the VII century. The latter considered the divine condition of Christ heretical, as well as the official language of their religion was ancient Syrian, differentiating itself from its Roman Catholic counterpart that used Latin.

Many of the pilgrims who settled in the vicinity of the holy land, however, during the trip and even when they were near the walls of the cities, robbers and bandits were frequent, always on the lookout for those who wanted to be defenseless. They did not have armed escorts. As a result of this situation in 1118, Hugo de Payens together with his entourage went to see King Baldwin to request his permission and some facilities so that he would approve a plan that was intended to help pilgrims heading to Jerusalem in those days. time. Thus, a military-religious order with chivalrous characteristics would be created, that of the Poor Knights of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon, which would later be called Knights Templar, which at first generated a contradiction with what religious orders had been until then. Baldwin gave them a space that would be known by Christians as the Temple of Solomon.

The first crusade succeeded in creating, in the territory of Palestine and Syria, the so-called Crusader States: the County of Edessa, the Principality of Antioch, the Kingdom of Jerusalem and the County of Tripoli. He also created allies along the Crusader route, such as the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia.

Back in Western Europe, those who had managed to survive to reach Jerusalem were greeted as heroes. Robert II of Flanders, for example, received the nickname Hierosolymitanus thanks to his achievements. Godfrey de Bouillon's life, for his part, became the subject of legends a few years after his death. However, in some cases the political situation in the places of origin was greatly affected by the absences of the crusaders. While Robert II of Normandy was away, control of England passed to his brother Henry I, and the conflict on his return led to the Battle of Tinchebray in 1106.

Meanwhile, the creation of the Crusader States was a relief for the Byzantine Empire, which it helped contain the pressure of the Seljuks, and which allowed it to recover several of its territories in Anatolia. The Empire subsequently went through, throughout the 12th century, a period of relative peace and prosperity. However, although this first crusade can be considered as a support, in dealing with the growing Seljuk threat and establishing small border kingdoms; the subsequent crusades, very ineffective against the Muslims, only managed to weaken the Byzantine Empire more and more, in whose internal affairs they intervened.

The effect on the eastern Muslim dynasties was more gradual, but important. The political instability and the division of the Great Seljuk Empire after the death of Malik Shah I prevented a coherent defense against the invasion of the Latin states. That same cooperation remained difficult for many decades, though from Egypt to Syria to Baghdad there began to be calls for the expulsion of the Crusaders. Ultimately this would culminate in Saladin's recapture of Jerusalem, after the Ayyubid dynasty had succeeded in unifying the surrounding areas.

Pope Urban II, in calling for a crusade to the Holy Land, sought to reinforce his supreme spiritual authority over Latin Christendom while expanding his area of power. He was unsuccessful in reuniting the existing schism between East and West, and inadvertently helped to solidify the schism, especially after the sack of Constantinople in the last Crusades.

Impact of the first crusade on art and literature

The success of the crusade inspired the poets of France who, in the 12th century, dedicated themselves to composing several epic songs that extolled and celebrated the achievements of Godfrey de Bouillon and the other crusaders. Some of these, such as the Song of Antioch, one of the most famous, are semi-historical, while others are completely fanciful, going so far as to describe battles with dragons or connect Godfrey's ancestors with the legend of the Knight of the Swan. In general, this group of songs is called the Cycle of the Crusades.

The crusade also inspired later artists. In 1580, Torquato Tasso wrote the epic poem Jerusalem Freed. Georg Friedrich Händel composed music based on that poem for his opera Rinaldo. For his part, Tommaso Grossi, poet of the XIX century, wrote another epic poem that would be the basis of Giuseppe Verdi's opera entitled I Lombardi alla prima crociata.

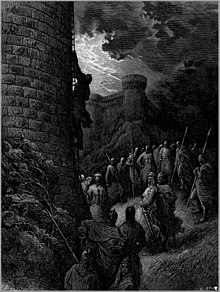

Gustave Doré, for his part, made a series of engravings based on episodes of the First Crusade.

The Crusades seen by the Arabs

The military phenomenon known as the crusades was perceived by the Muslim world as a barbaric invasion carried out by religious fanatics (called rum and frany by Muslims) with a cultural level much lower than that enjoyed in the Arab world at that time. In this sense, Amin Maalouf describes in his work The Crusades seen by the Arabs the point of view of the Muslim side, based on the testimonies of Arab historians and chroniclers of the time.

From this point of view, Amin Maalouf presents the first crusade as the beginning of two centuries of war in which the inhabitants of towns such as Jerusalem, Antioch, Tripoli or Tire suffered sieges, massacres and atrocities of all kinds, and whose This memory remained in popular Muslim culture, accentuating the cultural differences between Christian and Islamic civilizations, marking the history of the region up to the present day.

Fonts

Primary sources

Contenido relacionado

Hugo Boss AG

Gaucho

Knesset