Expressionism

Expressionism was a cultural movement that emerged in Germany at the beginning of the 20th century, which was reflected in a large number of fields: plastic arts, architecture, literature, music, cinema, theater, dance, photography etc Its first manifestation was in the field of painting, coinciding in time with the appearance of French Fauvism, a fact that made both artistic movements the first exponents of the so-called "historical avant-garde". More than a style with its own common characteristics, it was a heterogeneous movement, an attitude and a way of understanding art that brought together artists of very different tendencies, as well as of different training and intellectual levels. Emerged as a reaction to impressionism, as opposed to naturalism and the positivist nature of this movement at the end of the 19th century, the expressionists defended a more personal and intuitive art, where the interior vision of the artist —the “expression”— predominated as opposed to the embodiment of reality—the “impression”—

Expressionism is usually understood as the distortion of reality to express nature and the human being in a more subjective way, giving primacy to the expression of feelings rather than to the objective description of reality. Understood in this way, expressionism can be extrapolated to any era and geographical space. Thus, the work of various authors such as Matthias Grünewald, Pieter Brueghel the Elder, El Greco or Francisco de Goya has often been described as expressionist. Some historians, to distinguish it, write "expressionism" -in lower case- as a generic term and "Expressionism" -in capital letters- for the German movement.

With its violent colors and its themes of loneliness and misery, Expressionism reflected the bitterness that pervaded artistic and intellectual circles in pre-war Germany, as well as in the First World War (1914-1918) and the period of between the wars (1918-1939). That bitterness provoked a vehement desire to change life, to seek new dimensions to the imagination and to renew artistic languages. Expressionism defended individual freedom, the primacy of subjective expression, irrationalism, passion, and forbidden themes –the morbid, demonic, sexual, fantastic or perverted–. He tried to reflect a subjective vision, an emotional distortion of reality, through the expressive nature of plastic media, which gained metaphysical significance, opening the senses to the inner world. Understood as a genuine expression of the German soul, its existentialist character, its metaphysical longing and the tragic vision of the human being in the world made it a reflection of an existential conception released to the world of the spirit and to the concern for life and death, a conception that is usually described as "Nordic" for being associated with the temperament that is topically identified with the stereotype of northern European countries. A faithful reflection of the historical circumstances in which it developed, expressionism revealed the pessimistic side of life, the existential anguish of the individual, who in modern, industrialized society, is alienated, isolated. Thus, by distorting reality, they intended to impact the viewer, reach their most emotional and inner side.

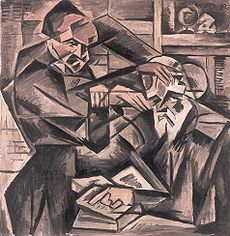

Expressionism was not a homogeneous movement, but one of great stylistic diversity: there is a modernist expressionism (Munch), Fauvist (Rouault), cubist and futurist (Die Brücke), surrealist (Klee), abstract (Kandinsky), etc. Although its greatest diffusion center was in Germany, it is also perceived in other European artists (Modigliani, Chagall, Soutine, Permeke) and Americans (Orozco, Rivera, Siqueiros, Portinari). In Germany it was organized mainly around two groups: Die Brücke (founded in 1905), and Der Blaue Reiter (founded in 1911), although there were some artists not affiliated with no group. After the First World War, the so-called New Objectivity appeared, which, although it arose as a rejection of expressionist individualism, defending a more social nature of art, its formal distortion and its intense color make them direct heirs of the first expressionist generation.

Definition

The transition from the 19th century to the XX brought with it numerous political, social and cultural changes. On the one hand, the political and economic rise of the bourgeoisie, which lived in the last decades of the XIX century (the Belle Époque) a moment of great splendor, reflected in modernism, an artistic movement at the service of luxury and ostentation displayed by the new ruling class. However, the revolutionary processes carried out since the French Revolution (the last, in 1871, the failed Paris Commune) and the fear that they would be repeated led the political classes to make a series of concessions, such as labor reforms, insurance social and compulsory basic education. Thus, the decrease in illiteracy led to an increase in the media and a greater diffusion of cultural phenomena, which acquired greater scope and greater speed of diffusion, emerging "mass culture".

On the other hand, technical advances, especially in the field of art, the appearance of photography and cinema, led the artist to consider the function of his work, which no longer consisted of imitating reality, since new techniques made it more objective, easy and reproducible. Likewise, the new scientific theories led artists to question the objectivity of the world we perceive: Einstein's theory of relativity, Freud's psychoanalysis and Bergson's subjectivity of time caused the artist to move further and further away from reality.. Thus, the search for new artistic languages and new forms of expression led to the appearance of avant-garde movements, which implied a new relationship between the artist and the viewer: avant-garde artists sought to integrate art with life, with society, make his work is an expression of the collective unconscious of the society he represents. At the same time, the interaction with the viewer causes them to become involved in the perception and understanding of the work, as well as in its dissemination and commodification, a factor that will lead to a greater rise in art galleries and museums.

Expressionism is part of the so-called “historical avant-garde”, that is, those produced from the first years of the XX century, in the pre-World War I environment, until the end of World War II (1945). This denomination also includes Fauvism, Cubism, Futurism, Constructivism, Neoplasticism, Dadaism, Surrealism, etc. The avant-garde is closely linked to the concept of modernity, characterized by the end of determinism and the supremacy of religion, replaced by reason and science, objectivism and individualism, trust in technology and progress, in their own capabilities of the human being. Thus, the artists intend to put themselves at the forefront of social progress, express through their work the evolution of the contemporary human being.

The term «expressionisme» was used for the first time by the French painter Julien-Auguste Hervé, who used the word “expressionisme” to designate a series of paintings presented at the Salon des Indépendants in Paris in 1901, as opposed to impressionism. The German term «Expressionismus» was adapted directly from French –since the expression in German is 'Ausdruck'–, being used for the first time in the catalog of the XXII Exhibition of the Berlin Secession in 1911, which included works by both German and French artists. In literature, it was applied for the first time in 1911 by the critic Kurt Hiller. Later, the term expressionism was spread by the writer Herwarth Walden, editor of the magazine Der Sturm (The Storm), which became the main center of dissemination of German expressionism. Walden initially applied the term to all the avant-garde movements that emerged between 1910 and 1920. Instead, the application of the term expressionism exclusively linked to German avant-garde art was the idea of Paul Fechter in his book Der Expressionismus (1914)., who following Worringer's theories related the new artistic manifestations as an expression of the German collective soul.

Expressionism arose as a reaction to impressionism: just as the impressionists captured on canvas an “impression” of the surrounding world, a simple reflection of the senses, the expressionists sought to reflect their inner world, an “expression” of their own feelings. Thus, the expressionists used line and color in a temperamental and emotional way, with a strong symbolic content. This reaction to impressionism marked a strong break with the art produced by the preceding generation, making expressionism synonymous with modern art during the early years of the century XX. Expressionism represented a new concept of art, understood as a way of capturing existence, of translucent in images the substratum that underlies apparent reality, of reflecting the immutable and eternal nature of the human being and nature. Thus, expressionism was the starting point of a process of transmutation of reality that crystallized in abstract expressionism and informalism. The expressionists used art as a way of reflecting their feelings, their state of mind, generally prone to melancholy, to evocation, to a neo-romantic decadence. Thus, art was a cathartic experience, where the spiritual outbursts, the vital anguish of the artist, were purified.

In the genesis of expressionism, a fundamental factor was the rejection of positivism, scientific progress, the belief in the unlimited possibilities of the human being based on science and technology. Instead, a new climate of pessimism, skepticism, discontent, criticism, and loss of values began to be generated. A crisis in human development was looming, which was effectively confirmed with the outbreak of the First World War. Also noteworthy in Germany was the rejection of the imperialist regime of Wilhelm II by an intellectual minority, drowned out by the pan-German militarism of the kaiser. These factors fostered a breeding ground in which expressionism gradually developed, whose first manifestations occurred in the field of literature: Frank Wedekind denounced bourgeois morality in his works, against which he opposed the passionate freedom of instincts.; Georg Trakl escaped from reality by taking refuge in a spiritual world created by the artist; Heinrich Mann was the one who most directly denounced the Wilhelmine society.

The appearance of expressionism in a country like Germany was not a random event, but is explained by the deep study devoted to art during the century XIX by German philosophers, artists and theorists, from romanticism and the multiple contributions to the field of aesthetics by characters such as Wagner and Nietzsche, to cultural aesthetics and the work of authors such as Konrad Fiedler (To judge works of visual art, 1876), Theodor Lipps (Aesthetics, 1903-1906) and Wilhelm Worringer (Abstraction and Empathy, 1908). This theoretical current left a deep mark on German artists of the late XIX and early 20th centuries, focused above all on the the artist's need to express himself (the "inner Drang" or inner need, a principle that Kandinski later assumed), as well as the confirmation of a break between the artist and the outside world, the environment that surrounds him, a fact that makes him a introverted and alienated from society. It was also influenced by the change produced in the cultural environment of the time, which moved away from the classical Greco-Roman taste to admire popular, primitive and exotic art -especially from Africa, Oceania and the Far East-, as well as medieval art and the work of artists such as Grünewald, Brueghel and El Greco.

In Germany, expressionism was more of a theoretical concept, an ideological proposal, than a collective artistic program, although a common stylistic stamp is appreciated among all its members. Faced with the prevailing academicism in the official art centers, the expressionists grouped around various centers for the diffusion of the new art, especially in cities such as Berlin, Cologne, Munich, Hannover and Dresden. Likewise, its diffusion work through publications, galleries and exhibitions helped to spread the new style throughout Germany and, later, throughout Europe. It was a heterogeneous movement that, apart from the diversity of its manifestations, carried out in different languages and artistic mediums, presented numerous differences and even contradictions within it, with great stylistic and thematic divergence between the various groups that emerged over time, and even among the artists that made them up. Even the chronological and geographical limits of this current are imprecise: although the first expressionist generation (Die Brücke, Der Blaue Reiter) was the most emblematic, the New Objectivity and the Exportation of the movement to other countries supposed its continuity in time at least until the Second World War; Geographically, although the nerve center of this style was located in Germany, it soon spread to other European countries and even to the American continent.

After the First World War, expressionism passed in Germany from painting to cinema and theater, which used the expressionist style in their sets, but in a purely aesthetic way, devoid of its original meaning, subjectivity and heartbreak typical of expressionist painters, who paradoxically became cursed artists. With the advent of Nazism, expressionism was considered "degenerate art" (Entartete Kunst), relating it to communism and calling it immoral and subversive, while they considered that their ugliness and artistic inferiority were a sign of the decadence of modern art (decadentism, for its part, had been an artistic movement that had some development). In 1937 an exhibition was organized at the Hofgarten in Munich with the title precisely Degenerate Art, with the aim of insulting it and showing the public the low quality of the art produced in the Weimar Republic. For this purpose, some 16,500 works from various museums were confiscated, not only by German artists, but also by foreign artists such as Gauguin, Van Gogh, Munch, Matisse, Picasso, Braque, Chagall, etc. Most of these works were later sold to gallery owners and dealers, most notably at a large auction held in Lucerne in 1939, although some 5,000 of these works were directly destroyed in March 1939, causing considerable damage to German art.

After the Second World War, expressionism disappeared as a style, although it exerted a powerful influence on many artistic currents of the second half of the century, such as American abstract expressionism (Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning), informalism (Jean Fautrier, Jean Dubuffet), the CoBrA group (Karel Appel, Asger Jorn, Corneille, Pierre Alechinsky) and German neo-expressionism –directly heir to the artists of Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter , which is evident in his name–, and individual artists such as Francis Bacon, Antonio Saura, Bernard Buffet, Nicolas de Staël, Horst Antes, etc.

Origins and influences

Although the art movement that developed in Germany at the turn of the 20th century is primarily known as Expressionism, many art historians and critics art also use this term in a more generic way to describe the style of a great variety of artists throughout history. Understood as the distortion of reality to seek a more emotional and subjective expression of nature and the human being, expressionism can therefore be extrapolated to any time and geographical space. Thus, the work of various authors such as Hieronymus Bosch, Matthias Grünewald, Quentin Metsys, Pieter Brueghel the Elder, El Greco, Francisco de Goya, Honoré Daumier, etc. has often been described as expressionist.

The roots of Expressionism lie in styles such as Symbolism and Post-Impressionism, as well as in the Nabis and artists such as Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, and Vincent Van Gogh. Likewise, they have points of contact with Neo-Impressionism and Fauvism due to their experimentation with color. The Expressionists received numerous influences: first of all, that of medieval art, especially German Gothic. With a religious sign and a transcendent character, medieval art placed emphasis on expression, not on forms: the figures had little corporeality, losing interest in reality, proportions, perspective. Instead, he accentuated the expression, especially in the look: the characters were symbolized rather than represented. Thus, the expressionists were inspired by the main artists of the German Gothic, developed through two fundamental schools: the international style (late 14th century-first half of the 15th century), represented by Conrad Soest and Stefan Lochner; and the Flemish style (second half of the 15th century century), developed by Konrad Witz, Martin Schongauer and Hans Holbein the Elder. They were also inspired by German Gothic sculpture, which stood out for its great expressiveness, with names like Veit Stoss and Tilman Riemenschneider. Another point of reference was Matthias Grünewald, a late-medieval painter who, although he knew the innovations of the Renaissance, continued in a personal line, characterized by emotional intensity, an expressive formal distortion and intense incandescent colouring, as in his masterpiece, the Isenheim Altarpiece.

Another of the referents of expressionist art was primitive art, especially that of Africa and Oceania, spread since the end of the XIX century by ethnographic museums. The artistic vanguards found in primitive art greater freedom of expression, originality, new forms and materials, a new conception of volume and color, as well as a greater significance of the object, since in these cultures they were not simple works of art, but that they had a religious, magical, totemic, votive, sumptuary purpose, etc. They are objects that express a direct communication with nature, as well as with spiritual forces, with cults and rituals, without any type of mediation or interpretation.

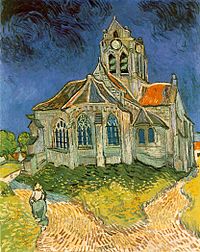

But his greatest inspiration came from Post-Impressionism, especially from the work of three artists: Paul Cézanne, who began a process of defragmenting reality into geometric shapes that led to Cubism, reducing shapes to cylinders, cones, and spheres, and dissolving the volume from the most essential points of the composition. He placed the color in layers, overlapping some colors with others, without the need for lines, working with spots. He did not use perspective, but the superimposition of warm and cold tones gave a sensation of depth. In second place, Paul Gauguin, who contributed a new conception between the pictorial plane and the depth of the painting, through flat and arbitrary colors, which have a symbolic and decorative value, with scenes that are difficult to classify, located between reality and a world dreamy and magical. His stay in Tahiti caused his work to drift towards a certain primitivism, influenced by oceanic art, reflecting the artist's inner world instead of imitating reality. Lastly, Vincent Van Gogh produced his work according to criteria of emotional exaltation, characterized by the lack of perspective, the instability of objects and colors, which border on arbitrariness, without imitating reality, but rather coming from within the artist. Due to his fragile mental health, his works reflect his depressive and tortured state of mind, which is reflected in works of sinuous brushstrokes and violent colors.

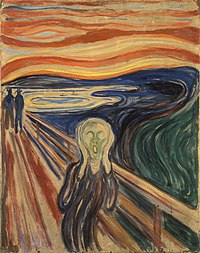

Ultimately, it is worth noting the influence of two artists that the expressionists considered as immediate precedents: the Norwegian Edvard Munch, influenced in his beginnings by impressionism and symbolism, soon drifted towards a personal style that would be a faithful reflection of his interior obsessive and tortured, with scenes of an oppressive and enigmatic environment –focused on sex, illness and death–, characterized by the sinuosity of the composition and a strong and arbitrary colouring. Munch's anguished and desperate images –as in The Scream (1893), a paradigm of loneliness and isolation– were one of the main starting points of Expressionism. Equally influential was the work of Belgian James Ensor, who collected the great artistic tradition of his country -especially Brueghel-, with a preference for popular themes, translating it into enigmatic and irreverent scenes, of an absurd and burlesque nature, with an acid and corrosive sense of humor, focused on figures of bums, drunks, skeletons, masks and carnival scenes. Thus, The Entry of Christ into Brussels represents the Passion of Jesus in the middle of a carnival parade, a work that caused a great scandal at the time.

Architecture

Expressionist architecture developed primarily in Germany, the Netherlands, Austria, Czechoslovakia, and Denmark. It was characterized by the use of new materials, sometimes caused by the use of biomorphic forms or by the expansion of possibilities offered by the mass production of construction materials such as brick, steel or glass. Many Expressionist architects fought in World War I, and their experience, combined with the political and social changes brought about by the German Revolution of 1918, led to utopian perspectives and a romantic socialist program. Expressionist architecture was influenced by modernism, especially from the work of architects such as Henry van de Velde, Joseph Maria Olbrich and Antoni Gaudí. Strongly experimental and utopian in nature, the achievements of the expressionists stand out for their monumentality, the use of brick and the subjective composition, which gives their works a certain air of eccentricity.

A theoretical contribution to expressionist architecture was the essay Glass Architecture (1914) by Paul Scheerbart, in which he attacked functionalism for its lack of artisticity and defended the replacement of brick by glass. Thus, for example, we can see the Glass Pavilion at the 1914 Cologne Exhibition, by Bruno Taut, an author who also put his ideas into writing (Alpine Architecture, 1919). Expressionist architecture developed in various groups, such as the Deutscher Werkbund, Arbeitsrat für Kunst, Der Ring and Neues Bauen, linked to the latter to the New Objectivity; It is also worth noting the Amsterdam School. The main expressionist architects were: Bruno Taut, Walter Gropius, Erich Mendelsohn, Hans Poelzig, Hermann Finsterlin, Fritz Höger, Hans Scharoun and Rudolf Steiner.

German Werkbund

The Deutscher Werkbund (German Federation of Labor) was the first architectural movement related to expressionism produced in Germany. Founded in Munich on October 9, 1907 by Hermann Muthesius, Friedrich Naumann and Karl Schmidt, it later incorporated figures such as Walter Gropius, Bruno Taut, Hans Poelzig, Peter Behrens, Theodor Fischer, Josef Hoffmann, Wilhelm Kreis, Adelbert Niemeyer, Richard Riemerschmid and Bruno Paul. Heir to the Jugendstil and the Viennese Sezession, and inspired by the Arts and Crafts movement, its objective was the integration of architecture, industry and crafts through professional work, education and advertising, as well as introducing architectural design into modernity and giving it an industrial character. The main characteristics of the movement were the use of new materials such as glass and steel, the importance of industrial design and decorative functionalism.

The Deutscher Werkbund organized various conferences that were later published in the form of yearbooks, such as Art in Industry and Commerce (1913) and Transportation (1914). Likewise, in 1914 they held an exhibition in Cologne that achieved great success and international diffusion, highlighting the glass and steel pavilion designed by Bruno Taut. The success of the exhibition led to a boom in the movement, which grew from 491 members in 1908 to 3,000 in 1929. During World War I it nearly disappeared, but it reemerged in 1919 after a convention in Stuttgart, where it was elected President Hans Poelzig –replaced in 1921 by Riemerschmidt–. During those years several controversies arose as to whether industrial or artistic design should take precedence, leading to various dissensions within the group.

In the 1920s the movement drifted from expressionism and crafts to functionalism and industry, incorporating new members such as Lilly Reich (first woman on the board) and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. A new magazine, Die Form (1922-1934), who spread the new ideas of the group, focused on the social aspect of architecture and urban development. In 1927 they held a new exhibition in Stuttgart, building a large housing colony, the Weissenhofsiedlung, designed by Mies van der Rohe and buildings built by Gropius, Behrens, Poelzig, Taut, etc., together with architects from outside Germany such as Jacobus Johannes Pieter Oud, Le Corbusier and Victor Bourgeois. This exhibition was one of the starting points of the new architectural style that was beginning to emerge, known as the international style or rationalism. The Deutscher Werkbund dissolved in 1934 mainly due to the economic crisis and Nazism. His spirit greatly influenced the Bauhaus, and inspired the founding of similar organizations in other countries, such as Switzerland, Austria, Sweden and Great Britain.

Amsterdam School

Parallel to the German Deutscher Werkbund, between 1915 and 1930 a notable expressionist architectural school developed in Amsterdam (Netherlands). Influenced by modernism (mainly Henry van de Velde and Antoni Gaudí) and by Hendrik Petrus Berlage, they were inspired by natural forms, with imaginatively designed buildings where the use of brick and concrete predominates. Its main members were Michel de Klerk, Piet Kramer and Johan van der Mey, who worked together countless times, contributing greatly to the urban development of Amsterdam, with an organic style inspired by traditional Dutch architecture, highlighting the undulating surfaces. His main works were the Scheepvaarthuis (Van der Mey, 1911-1916) and the Eigen Haard Estate (De Klerk, 1913-1920).

Arbeitsrat für Kunst

The Arbeitsrat für Kunst (Council of Art Workers) was founded in 1918 in Berlin by the architect Bruno Taut and the critic Adolf Behne. Emerged after the end of the First World War, its objective was the creation of a group of artists that could influence the new German government, with a view to the regeneration of national architecture, with a clear utopian component. His works stand out for the use of glass and steel, as well as for the imaginative forms charged with intense mysticism. They immediately attracted members from the Deutscher Werkbund, such as Walter Gropius, Erich Mendelsohn, Otto Bartning and Ludwig Hilberseimer, and they had the collaboration of other artists, such as the painters Lyonel Feininger, Erich Heckel, Karl Schmidt- Rottluff, Emil Nolde and Max Pechstein, and the sculptors Georg Kolbe, Rudolf Belling and Gerhard Marcks. This variety is explained because the aspirations of the group were more political than artistic, trying to influence the decisions of the new government regarding art and architecture. However, after the events of January 1919 related to the Spartacist League, the group renounced its political purposes, dedicating itself to organizing exhibitions. Taut resigned as president, being replaced by Gropius, although they were finally dissolved on May 30, 1921.

The Ring

The Der Ring (The Circle) group was founded in Berlin in 1923 by Bruno Taut, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Peter Behrens, Erich Mendelsohn, Otto Bartning, Hugo Häring and several other architects, to which Walter Gropius, Ludwig Hilberseimer, Hans Scharoun, Ernst May, Hans and Wassili Luckhardt, Adolf Meyer, Martin Wagner, etc., were soon added. His goal was, as in previous movements, to renew the architecture of his time, placing special emphasis on social and urban aspects, as well as research into new materials and construction techniques. Between 1926 and 1930 they carried out notable work in the construction of social housing in Berlin, with houses that stand out for their use of natural light and their location in green areas, highlighting the Hufeisensiedlung (Colonia de la Herradura, 1925-1930), by Taut and Wagner. Der Ring disappeared in 1933 after the rise of Nazism.

Neues Bauen

Neues Bauen (New Construction) was the name given in architecture to the New Objectivity, a direct reaction to the stylistic excesses of Expressionist architecture and the change in the national mood, in in which the social component predominated over the individual. Architects such as Bruno Taut, Erich Mendelsohn and Hans Poelzig turned to the simple, functional and practical approach of the New Objectivity. The Neues Bauen flourished in the short period between the adoption of the Dawes plan and the rise of Nazism, encompassing public exhibitions such as the Weißenhofsiedlung, extensive urban planning and public promotion projects of Taut and Ernst May, and the influential experiments of the Bauhaus.

Sculpture

Expressionist sculpture did not have a common stylistic stamp, being the individual product of various artists who reflected in their work either the theme or the formal distortion of expressionism. Three names stand out in particular:

- Ernst Barlach: inspired by Russian popular art – after a trip to the Slavic country in 1906– and the German medieval sculpture, as well as in Brueghel and El Bosco, his works have a certain caricaturesque air, working much on the volume, depth and articulation of the movement. He developed two main themes: the popular (daily used, peasant scenes) and – especially after the war – fear, anguish, terror. It did not imitate reality, but created a new reality, playing with broken lines and angles, with anatomies separated from naturalism, tending to geometry. He worked preferably in wood and plaster, which sometimes later passed to bronze. Among his works are: The fugitive (1920-1925), The avenger (1922), Death in life (1926), The flautist (1928), The drinker (1933), Old cold (1939), etc.

- Wilhelm Lehmbruck: educated in Paris, his work has a marked classicist character, although deformed and stylized, and with a strong introspective and emotional burden. During his formation in Düsseldorf he evolved from a naturalism of sentimental cutting, through a baroque dramatism with Rodin's influence, to a realism influenced by Meunier. In 1910 he settled in Paris, where he accused the influence of Maillol. Finally, after a trip to Italy in 1912, a greater geometry and stylization of the anatomy began, with a certain medieval influence on the lengthening of its figures (Ripped woman1911; Young stand1913).

- Käthe Kollwitz: wife of a doctor in a poor neighborhood in Berlin, knew closely the human misery, which marked her deeply. Socialist and feminist, his work has a marked component of social vindication, with sculptures, lithographs and etchings that stand out for its crudeness: The revolt of the weavers (1907-1908), The War of the Peasants (1902-1908), Tribute to Karl Liebknecht (1919-1920).

The members of Die Brücke (Kirchner, Heckel, Schmidt-Rottluff) also practiced sculpture, since their experimentation with woodcuts allowed them to easily move on to wood carving, a material they found very suitable for his intimate expression of reality, since the roughness and irregular appearance of this material, its raw and unfinished appearance, even primitive, were the perfect expression of his concept of the human being and nature. The influence of African and Oceanic art is perceived in these works, whose simplicity and totemic aspect were praised, which transcends art to be the object of transcendental communication.

In the 1920s, sculpture drifted towards abstraction, following the course of Lehmbruck's latest works, with marked geometric stylization tending towards abstraction. Thus, the work of sculptors such as Rudolf Belling, Oskar Schlemmer and Otto Freundlich was characterized by the abandonment of figuration in favor of a formal and thematic liberation of sculpture. However, a certain classicism lasted, influenced by Maillol, in the work of Georg Kolbe, dedicated especially to the nude, with dynamic figures, in rhythmic movements close to ballet, with a vital, happy and healthy attitude that was well received by the Nazis.. His most famous work was La Mañana, exhibited in the German Pavilion built by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe for the 1929 Barcelona International Exposition. Gerhard Marcks produced an equally figurative work, but more static and of more expressive and complex theme, with archaic-looking figures, inspired by medieval carvings. Ewald Mataré devoted himself mainly to animals, in almost abstract forms, following the path begun by Marc in Der Blaue Reiter. Other expressionist sculptors included Bernhard Hoetger, Ernst Oldenburg and Renée Sintenis, while outside of Germany include Antoine Bourdelle from France, Jacob Epstein from Britain, Ivan Meštrović from Croatia, Victorio Macho from Spain, Lambertus Zijl from the Netherlands, August Zamoyski from Poland and Wäinö Aaltonen from Finland.

Painting

Painting developed mainly around two artistic groups: Die Brücke, founded in Dresden in 1905, and Der Blaue Reiter, founded in Munich in 1911. In After the war, the New Objectivity movement emerged as a counterweight to Expressionist individualism, defending a more socially committed attitude, although technically and formally it was a movement that inherited Expressionism. The most characteristic elements of expressionist works of art are colour, dynamism and feeling. The fundamental thing for the painters of the beginning of the century was not to reflect the world in a realistic and faithful way –just the opposite of the Impressionists– but, above all, to express their inner world. The primary objective of the expressionists was to convey their deepest emotions and feelings.

In Germany, the first expressionism was heir to the post-romantic idealism of Arnold Böcklin and Hans von Marées, focusing mainly on the meaning of the work, and giving greater relevance to drawing as opposed to brushstrokes, as well as composition and structure of the painting. Likewise, the influence of foreign artists such as Munch, Gauguin, Cézanne and Van Gogh was paramount, reflected in various exhibitions organized in Berlin (1903), Munich (1904) and Dresden (1905).

Expressionism stood out for the large number of artistic groups that arose within it, as well as for the multitude of exhibitions held throughout Germany between 1910 and 1920: in 1911 the New Secession was founded in Berlin, a split of the Berlin Secession founded in 1898 and chaired by Max Liebermann. Its first president was Max Pechstein, and it included Emil Nolde and Christian Rohlfs. Later, in 1913, the Free Secession arose, an ephemeral movement that was eclipsed by the Herbstsalon (Autumn Salon) of 1913, promoted by Herwarth Walden, where together with the main German expressionists, various cubist and futurist artists exhibited, highlighting Chagall, Léger, Delaunay, Mondrian, Archipenko, Hans Arp, Max Ernst, etc. However, despite its artistic quality, the exhibition was an economic failure, so the initiative was not repeated.

Expressionism had a notable presence, in addition to Berlin, Munich and Dresden, in the Rhineland region, where Macke, Campendonk and Morgner came from, as well as other artists such as Heinrich Nauen, Franz Henseler, Paul Adolf Seehaus, etc.. In 1902, the philanthropist Karl Ernst Osthaus created the Folkwang (People's Hall) in Hagen, with the aim of promoting modern art, acquiring numerous works by expressionist artists as well as Gauguin, Van Gogh, Cézanne, Matisse, Munch, etc. Likewise, in Düsseldorf a group of young artists founded the Sonderbund Westdeutscher Kunstfreunde und Künstler (Special League of West German art enthusiasts and artists), which held various exhibitions from 1909 to 1911, moving in 1912 to Cologne, where, despite the success after this last exhibition, the league was dissolved.

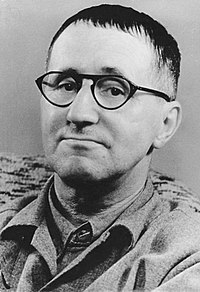

In the postwar period, the Novembergruppe (November Group, due to the German revolution of November 1918) arose, founded in Berlin on December 3, 1918 by Max Pechstein and César Klein, with the aim of reorganizing German art after the war. Its members included painters and sculptors such as Wassily Kandinski, Paul Klee, Lyonel Feininger, Heinrich Campendonk, Otto Freundlich and Käthe Kollwitz; architects like Walter Gropius, Erich Mendelsohn, and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe; composers like Alban Berg and Kurt Weill; and the playwright Bertolt Brecht. More than a group with a common stylistic seal, it was an association of artists with the aim of exhibiting together, which they did until they dissolved with the arrival of Nazism.

Die Brucke

Die Brücke (The Bridge) was founded on June 7, 1905 in Dresden by four architecture students from the Dresden Higher Technical School: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Fritz Bleyl, Erich Heckel and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. The name was devised by Schmidt-Rottluff, symbolizing through a bridge his claim to lay the foundations for future art. Possibly the inspiration came from a phrase from Nietzsche's Thus Spoke Zarathustra: "The greatness of man is that he is a bridge and not an end." In 1906 Emil Nolde and Max Pechstein joined the group., as well as the Swiss Cuno Amiet and the Dutch Lambertus Zijl; in 1907, the Finn Akseli Gallen-Kallela; in 1908, Franz Nölken and the Dutch Kees Van Dongen; and, in 1910, Otto Mueller and the Czech Bohumil Kubišta. Bleyl separated from the group in 1907, moving to Silesia, where he taught at the School of Civil Engineering, abandoning painting. In its beginnings, the members of Die Brücke worked in a small workshop located at 65 Berliner Straße in Dresden, acquired by Heckel in 1906, which they themselves decorated and furnished following the guidelines of the group.

The group Die Brücke sought to connect with the general public, involving them in the group's activities. They devised the figure of the “passive member”, who, through an annual subscription of twelve marks, periodically received a newsletter with the activities of the group, as well as various engravings (the “Brücke-Mappen”). Over time the number of passive members rose to sixty-eight. In 1906 they published a manifesto, Programm, where Kirchner expressed his desire to summon the youth for a social art project that would transform the future. They tried to influence society through art, considering themselves revolutionary prophets who would manage to change the society of their time. The intention of the group was to attract any revolutionary element that wanted to join; This is how they expressed it in a letter addressed to Nolde. His greatest interest was to destroy the old conventions, just as was being done in France. According to Kirchner, there could be no rules and inspiration had to flow freely and give immediate expression to the artist's emotional pressures. The burden of social criticism that they imprinted on his work earned them attacks from conservative critics who accused them of being a danger to German youth.

The artists of Die Brücke were influenced by the Arts and Crafts movement, as well as Jugendstil and Nabis, and artists such as Van Gogh, Gauguin and Munch. They were also inspired by German Gothic and African art, especially after Kirchner's studies of Dürer's woodcuts and of African art in the Dresden Ethnological Museum. They were also interested in Russian literature, especially Dostoyevsky. In 1908, after a Matisse exhibition in Berlin, they also expressed their admiration for the Fauves, with whom they shared the simplicity of the composition, the mannerism of the forms and the intense contrast of colours. Both started from post-impressionism, rejecting imitation and emphasizing the autonomy of color. However, the thematic contents vary: the expressionists were more distressing, marginal, unpleasant, and emphasized sex more than the fauves. They rejected academicism and alluded to the "maximum freedom of expression." More than their own stylistic program, their link was the rejection of realism and impressionism, and their search for an artistic project that involved art with life, for which they experimented with various artistic techniques such as murals, xylography and cabinetmaking, apart from painting and sculpture.

Die Brücke gave special importance to graphic works: their main means of expression was xylography, a technique that allowed them to express their conception of art in a direct way, leaving an unfinished, rough, wild, close to the primitivism that they admired so much. These wood engravings present irregular surfaces, which they do not hide and take advantage of in an expressive way, applying color spots and highlighting the sinuosity of the forms. They also used lithography, aquatint and etching, which tend to have a reduced chromaticism and stylistic simplification. Die Brücke defended the direct and instinctive expression of the artist's creative impulse, without norms or rules, rejecting totally any type of academic regulation. As Kirchner said: "the painter transforms his conception of his experience into a work of art."

The members of Die Brücke were interested in a type of theme centered on life and nature, reflected spontaneously and instinctively, so their main themes are the nude –whether indoors or exterior–, as well as circus and music-hall scenes, where they find the maximum intensity they can extract from life. This theme was synthesized in works about bathers that its members produced preferably between 1909 and 1911 during their stays in the lakes Close to Dresden: Alsen, Dangast, Nidden, Fehmarn, Hiddensee, Moritzburg, etc. They are works where they express openly naturism, an almost pantheistic feeling of communion with nature, while technically they refine their palette, in a process of subjective deformation of shape and color, which acquires a symbolic meaning.

In 1911 most of the artists in the group settled in Berlin, beginning their solo careers. In the German capital they received the influence of cubism and futurism, evident in the schematization of forms and in the use of colder tones from then on. Its palette became darker and its theme more desolate, melancholic, pessimistic, losing the common stylistic stamp they had in Dresden to run increasingly divergent paths, each beginning their personal journey. One of the largest exhibitions where the members participated of Die Brücke was the Sonderbund in Cologne in 1912, where Kirchner and Heckel were also commissioned to decorate a chapel, which was a great success. Even so, in 1913 the group formally dissolved, due to the rejection that Kirchner's publication of the history of the group (Chronicle of the Die Brücke Art Society) provoked in his colleagues, where he gave himself a special relevance that was not accepted by the rest of the members.

The main members of the group were:

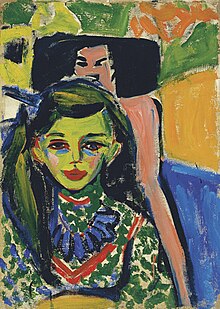

- Ernst Ludwig Kirchner: a great sketch artist – his father was a drawing teacher – from his visit to a Durer xilography exhibition in 1898 he began to make wood engravings, material in which he also made African influence sizes, with an irregular finish, without polishing, highlighting the sexual components. He used primary colors, such as the fauvists, with a certain influence of Matisse, but with broken, violent lines – unlike the rounded Matisse – in closed, sharp angles. The figures are stylized, with an elongation of Gothic influence. Since his transfer to Berlin in 1910 he made more schematic compositions, with cutting lines and unfinished areas, and some formal distortion. Progressively his brushstroke became more nervous, aggressive, with superimposed lines, more geometric composition, with angular shapes inspired by cubist decomposition. Since 1914 he began to suffer from mental disorders and, during the war, he suffered respiratory disease, factors that influenced his work. In 1937 his works were confiscated by the Nazis, killing himself the following year.

- Erich Heckel: his work was nourished by Van Gogh's direct influence, which he met in 1905 at the Arnold Gallery of Dresden. Between 1906 and 1907 he made a series of paintings of vangoghiana composition, of short brushstrokes and intense colors –predominantly yellow–, with dense pasta. Later he evolved into more expressionist themes, such as sex, loneliness, incommunicado, etc. He also worked with wood, in linear works, without perspective, with Gothic and Cubist influence. He was one of the most linked expressionists to the German Romantic current, which is reflected in his utopian view of the marginal classes, for which he expresses a feeling of solidarity and vindication. Since 1909 he made a series of trips all over Europe that brought him into contact with both ancient art and the new avant-garde, especially fauvism and cubism, of which he adopts the spatial organization and the intense and subjective colouring. In his works he tends to neglect the figurative and descriptive aspect of his compositions to highlight the emotional and symbolic content, with dense brushstrokes that make the color occupy all the space, without giving importance to drawing or composition.

- Karl Schmidt-Rottluff: in its beginnings he practiced macropuntillism, to pass to an expressionism of schematic figures and cutting faces, of loose brushstroke and intense colors. He received some influence from Picasso in his blue phase, as well as Munch and African art and, since 1911, Cubism, palpable in the simplification of the forms he applied to his works since. Given a great master's degree for the watercolor, he knew how to double the colors very well and distribute the light, while in painting he applied dense and thick brushstrokes with a clear precedent in Van Gogh. He also made wood carvings, sometimes polychrome, with African influence – elongated faces, almond eyes.

- Emil Nolde: linked to Die Brücke During 1906-1907, he worked solo, dissatisfied with tendencies – he was not considered an expressionist, but a “German artist”. Dedicated in principle to landscape painting, floral and animal themes, he felt predilection by Rembrandt and Goya. At the beginning of the century he used the divisional technique, with very thick filling and short brushstrokes, and with strong chromatic discharge, of post-printing influence. During your stay Die Brücke He abandoned the process of imitation of reality, denoting in his work an inner concern, a vital tension, a crispation that is reflected in the inner pulse of the work. Then began the religious themes, focusing on the Passion of Christ, with the influence of Grünewald, Brueghel and El Bosco, with disfigured faces, a deep feeling of anguish and a great exaltation of color (Last dinner1909; Pentecost1909; Santa María Egipcíaca1912).

- Otto Mueller: a great admirer of Egyptian art, performed works on landscapes and nude with schematic and angulous forms where the influence of Cézanne and Picasso is perceived. His nudes tend to be in natural landscapes, showing the influence of Gauguin's exotic nature. Its drawing is clean and fluid, away from the rough and gestual style of the other expressionists, with a composition of flat surfaces and soft curved lines, creating an atmosphere of idyllic ensuing. Its thin and slender figures are inspired by Cranach, whose Venus He had a reproduction in his study. They are naked of great simplicity and naturality, without traits of provocation or sensuality, expressing an ideal perfection, the nostalgia of a lost paradise, in which the human being lived in communion with nature.

- Max Pechstein: from academic background, studied Fine Arts in Dresden. On a trip to Italy in 1907 he was enthusiastic about Etruscan art and mosaics of Rávena, while in his next stay in Paris he came into contact with Fauvism. In 1910 he was a founder with Nolde and Georg Tappert of the New Berlin Secession, of which he was his first president. In 1914 he made a trip through Oceania, receiving as many other artists of the time the influence of primitive and exotic art. His works tend to be solitary landscapes and agress, usually from Nidden, a population of the Baltic coast that was his place of summer.

Der Blaue Reiter

Der Blaue Reiter ("The Blue Rider") arose in Munich in 1911, bringing together Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, August Macke, Paul Klee, Gabriele Münter, Alfred Kubin, Alexej von Jawlensky, Lyonel Feininger, Heinrich Campendonk and Marianne von Werefkin. The name of the group was chosen by Marc and Kandinski having coffee on a terrace, after a conversation where they agreed on their taste for horses and the color blue, although it is noteworthy that Kandinski already painted a painting with the title The Blue Rider in 1903 (E.G. Bührle Collection, Zürich). Again, more than a common stylistic stamp, they shared a certain vision of art, in which the creative freedom of the artist and the personal and subjective expression of his ideas prevailed. plays. Der Blaue Reiter was neither a school nor a movement, but a group of artists with similar concerns, centered on a concept of art not as imitation, but as an expression of the artist's interior.

Der Blaue Reiter was a splinter group of the Neue Künstlervereinigung München (New Association of Artists in Munich), founded in 1909, of which Kandinsky was president, and which It also included Marc, Jawlensky, Werefkin, Kubin, Klee, Münter, the brothers David and Vladimir Burliuk, Alexander Kanoldt, Adolf Erbslöh, Karl Hofer, etc. However, aesthetic differences led to the abandonment of Kandinski, Marc, Kubin and Münter, founding the new group. Der Blaue Reiter had few points in common with Die Brücke, coinciding with basically in his opposition to impressionism and positivism; However, compared to the temperamental attitude of Die Brücke, compared to its almost physiological depiction of emotion, Der Blaue Reiter had a more refined and spiritual attitude, pretending to capture the essence of reality through the purification of instincts. Thus, instead of using physical deformation, they opt for its total purification, thus reaching abstraction. His poetics was defined as a lyrical expressionism, in which the escape was not directed towards the wild world but towards the spiritual of nature and the inner world.

The members of the group showed their interest in mysticism, symbolism and the forms of art that they considered most genuine: primitive, popular, infantile and mentally ill. Der Blaue Reiter stood out for its use of watercolor, compared to the engraving used mainly by Die Brücke. It is also worth noting the importance given to music, which is usually assimilated to color, which facilitated the transition from a figurative art to a more abstract one. In the same way, in their theoretical essays they showed their predilection for the abstract form, in which that they saw a great symbolic and psychological content, a theory that Kandinski expanded on in his work Of the spiritual in art (1912), where he sought a synthesis between intelligence and emotion, defending that art communicates with our inner spirit, and that artistic works can be as expressive as music. Kandinski expresses a mystical concept of art, influenced by theosophy and oriental philosophy: art is an expression of the spirit, artistic forms being a reflection of the same. As in Plato's world of ideas, shapes and sounds connect with the spiritual world through sensitivity, through perception. For Kandinski, art is a universal language, accessible to any human being. The path of painting had to be from the heavy material reality to the abstraction of pure vision, with color as a medium, for this reason he developed a complex theory of color: in Painting as pure art (1913) maintains that painting is already a separate entity, a world in itself, a new way of being, which acts on the viewer through sight and provokes deep spiritual experiences in him.

Der Blaue Reiter organized several exhibitions: the first was at the Thannhäuser Gallery in Munich, inaugurated on December 18, 1911 under the name I Ausstellung der Redaktion des Blauen Reiter (I Exhibition of the Directors of the Blue Rider). It was the most homogeneous, since a clear mutual influence was noted between all the members of the group, later dissipated by a greater individuality of all its members. Works exhibited were Macke, Kandinski, Marc, Campendonk and Münter and, as guests, Arnold Schönberg –composer but also author of pictorial works–, Albert Bloch, David and Vladimir Burliuk, Robert Delaunay and the Customsman Rousseau. The second exhibition was held at the Hans Goltz Gallery in March 1912, dedicated to watercolors and graphic works, confronting German Expressionism with French Cubism and Russian Suprematism. The last major exhibition took place in 1913 at the Der Sturm headquarters in Berlin, in parallel to the first Autumn Salon held in Germany.

One of the greatest milestones of the group was the publication of the Almanac (May 1912), on the occasion of the exhibition organized in Cologne by the Sonderbund. They did it in collaboration with the gallery owner Heinrich von Tannhäuser and with Hugo von Tschudi, director of the Bavarian museums. Along with numerous illustrations, it included various texts by members of the group, dedicated to modern art and with numerous references to primitive and exotic art. The pictorial theory of the group was shown, focused on the importance of color and the loss of realistic composition and the imitative nature of art, in the face of greater creative freedom and a more subjective expression of reality. There was also talk of the pioneers of the movement (Van Gogh, Gauguin, Cézanne, Rousseau), which included both the members of Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter as well as Matisse, Picasso and Delaunay. Music was also included, with references to Schönberg, Webern and Berg.

Der Blaue Reiter came to an end with the First World War, in which Marc and Macke died, while Kandinsky had to return to Russia. In 1924 Kandinski and Klee, together with Lyonel Feininger and Alexej von Jawlensky, founded Die Blaue Vier (The Blue Four) within the Bauhaus, jointly exhibiting their work for a period of ten years.

The main representatives of Der Blaue Reiter were:

- Vasili Kandinski: of late vocation, studied law, economy and politics before moving to painting, after visiting an Impressionist exhibition in 1895. Established in Munich, started in the Jugendstilconjuring it with elements of Russian tradition. In 1901 he founded the group PhalanxAnd he opened his own school. During 1906-1909 he had a fauvist period, to later pass to expressionism. Since 1908 his work was losing the thematic and figurative aspect to gain in expressivity and colour, progressively beginning the path to abstraction, and since 1910 he created paintings where the importance of the work resided in form and colour, creating pictorial planes by confronting colors. Its abstraction was open, with a focus on the center, pushing with a centrifugal force, deriving the lines and stains out, with great formal and chromatic richness. Kandinski himself distinguished his work between “impressions”, a direct reflection of the outer nature (which would be his work until 1910); “improvisions”, an expression of an internal sign, of a spontaneous character and of a spiritual nature (expressionist abstraction, 1910-1921); and “compositions”, an equally internal but slowly elaborated expression (constructive abstraction, since 1921).

- Franz Marc: student of theology, during a trip to Europe between 1902 and 1906 decided to become a painter. Drawing from a great mysticism, he was considered an “expressive” painter, trying to express his “inner self”. His work was quite monothematic, mainly devoted to animals, especially horses. Nevertheless, their treatments were very varied, with very violent contrasts of color, without linear perspective. He received the influence of Degas, who also made a series on horses, as well as the ophthalm of Delaunay and the floating atmospheres of Chagall. For Marc, art was a way of grasping the essence of things, which translated into a mystical and pantheistic view of nature, which he plastered above all in animals, which for him had a symbolic meaning, representing concepts such as love or death. In their animal representations the color was equally symbolic, highlighting the blue, the most spiritual color. The figures were simple, schematic, tending to geometry after their contact with cubism. However, derained also of the animals, he began as Kandinski the way to abstraction, a career that was truncated with his death in the world contest.

- August Macke: in 1906 he visited Belgium and the Netherlands, where he received the influence of Rembrandt – played thick, contrasts accused–; in 1907, in London, he was excited by the pre-Raphaelites; likewise, in 1908 in Paris he contacted the fauvism. Since then he abandoned tradition and renewed them and coloured, working with light and warm colors. Later he received the influence of Cubism: chromatic restriction, geometric lines, schematic figures, shade-light contrasts. Finally it came to abstract art, influenced by Kandinski and Delaunay: it made a rational, geometric abstraction, with linear colour stains and compositions based on colored geometric planes. In his last works – after a trip to North Africa – he returned to strong colorism and exaggerated contrasts, with a certain surreal air. It was inspired by everyday themes, in generally urban environments, with a lyric, cheerful, serene air, with symbolic expression colors like Marc.

- Paul Klee: of musical formation, in 1898 he went to painting, denoting as Kandinski a pictorial sense of musical evanescence, tending to abstraction, and with an unirical air that would lead him to surrealism. Initiated in the Jugendstil, and with influence of Arnold Böcklin, Odilon Redon, Vincent van Gogh, James Ensor and Kubin, pretended as the latter to achieve an intermediate state between reality and ideal dreaming. Later, after a trip to Paris in 1912 where he met Picasso and Delaunay, he became more interested in colour and compositive possibilities. On a trip to Africa in 1914 with Macke he reaffirmed his vision of color as a dynamizing element of the painting, which would be the basis of his compositions, where he endures the figurative form combined with a certain abstract atmosphere, in curious combinations that would be one of his most recognizable stylistic seals. Klee recreated in his work a fantastic and ironic world, close to that of children or madmen, which will bring him to the universe of surrealists – numerous points of contact have been pointed out between his work and that of Joan Miró.

- Alexej von Jawlensky: Russian military man, left his career to dedicate himself to art, in Munich in 1896 with Marianne von Werefkin. In 1902 he traveled to Paris, working in friendship with Matisse, with whom he worked for a while and with whom he began in the colorful fauve. It was mainly dedicated to the portrait, inspired by the icons of traditional Russian art, with figures in hierarchical attitude, of great size and compositive schematization. He worked with large colored surfaces, with a violent colour, delimited by strong black strokes. During the war he took refuge in Switzerland, where he made portraits close to Cubism, with oval faces, with elongated nose and asymmetric eyes. Later, by Kandinski influence, he approached abstraction, with portraits reduced to geometric shapes, intense and warm colors.

- Lyonel Feininger: American of German origin, in 1888 he traveled to Germany to study music and later went to painting. In his beginnings he worked as a cartoonist for several newspapers. It received the influence of Delaunay's ophthaltic cubism, patented in the geometry of its urban landscapes, in a narrow and disturbing manner, similar to those of de The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari – in which decorators probably influenced–. Its characters are caricaturescos, of great size – sometimes reaching the same height of the buildings–, built by superimposing of color planes. Professor of the Bauhaus From 1919 to 1933, in 1938, because of Nazism, he returned to his native New York.

- Gabriele Münter: studied in Düsseldorf and Munich, entering the group Phalanxwhere he met Kandinski, with whom he started a relationship and spent long seasons in the town of Murnau. There he painted numerous landscapes in which he revealed a great emotivity and a great mastery of colour, with influence of Bavarian popular art, which is denoted in the simple lines, light and bright colors and a careful distribution of the masses. He received from Jawlensky the juxtaposition of bright color stains with sharp outlines, which would become his main artistic seal. Between 1915 and 1927 he stopped painting, after his break with Kandinski.

- Heinrich Campendonk: influenced by the ophthal cubism and popular and primitive art, created a type of early-pointed works, with high rigidity drawing, hierarchical figures and scissors. In his works the contrast of colors has a decisive role, with a brushstroke heir of impressionism. Later, by Marc's influence, the color gained independence from the object, charging more expressive value, and decompositioning the space in the cubist way. It exceeded the colors in transparent layers, performing free compositions where objects seem to float on the surface of the picture. Like Marc, his theme focused on an idealized concept of communion between man and nature.

- Alfred Kubin: writer, cartoonist and illustrator, his work was based on a ghostly world of monsters, morbid and mind-boggling, reflecting his obsession with death. Influenced by Max Klinger, he worked mainly as an illustrator, in black and white drawings of decadent air with reminiscences of Goya, Blake and Félicien Rops. His scenes were framed in crepuscular, ghostly environments, which also remind Odilon Redon, with a calligraphic style, sometimes praying for abstraction. His fantastic, morbid images, with references to sex and death, were precursors of surrealism. He was also a writer, whose main work, The other side (1909), he may have influenced Kafka.

- Marianne von Werefkin: belonging to a Russian aristocratic family, received classes from Ilya Repin in St.Petersburg. In 1896 he moved to Munich with Jawlensky, with whom he had initiated a relationship, dedicating himself more to the diffusion of his work than to his own. In this city he created a hall of remarkable fame as an artistic tertulia, becoming influenced by Franz Marc at the theoretical level. In 1905, after some divergences with Jawlensky, he painted again. That year he traveled to France, receiving the influence of the Nabis and the Futurists. His works are of a bright colourful, full of contrasts, with preponderance of the line in the composition, to which the color is subordinated. The theme is strongly symbolic, highlighting its enigmatic landscapes with processions of the dead.

New Sachlichkeit

The Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) group arose after the First World War as a reaction movement against Expressionism, returning to realistic figuration and the objective representation of the surrounding reality, with a marked social and protest component. Developed between 1918 and 1933, it disappeared with the advent of Nazism. The atmosphere of pessimism that the postwar period brought led to the abandonment by some artists of the more spiritual and subjective expressionism, in search of new artistic languages, for a more committed art, more realistic and objective, hard, direct, useful for the development of society, a revolutionary art in its theme, although not in its form. The artists separated from abstraction, reflecting on figurative art and rejecting any activity that did not attend to the problems of the pressing reality of the postwar period. This group was incarnated by Otto Dix, George Grosz, Max Beckmann, Conrad Felixmüller, Christian Schad, Rudolf Schlichter, Ludwig Meidner, Karl Hofer and John Heartfield.

Faced with the psychological introspection of expressionism, the individualism of Die Brücke or the spiritualism of Der Blaue Reiter, the New Objectivity proposed a return to realism and objective representation of the surrounding world, with a more social and politically committed theme. However, they did not renounce the technical and aesthetic achievements of avant-garde art, such as Fauvist and Expressionist colouring, Futurist “simultaneous vision” or the application of photomontage to verismo painting and engraving. The recovery of figuration was a common consequence in space at the end of the war: in addition to the New Objectivity, purism arose in France and metaphysical painting, the precursor of surrealism, arose in Italy. But in the New Objectivity this realism is more committed than in other countries, with works of social denunciation that seek to unmask the bourgeois society of its time, denounce the political and military establishment that has led them to the disaster of war. Although the New Objectivity opposed Expressionism for being a spiritual and individualistic style, instead it maintained its formal essence, since its grotesque character, the distortion of reality, the caricature of life, was transferred to the social issues addressed by the new postwar artists.

The New Objectivity arose as a rejection of the Novembergruppe, whose lack of social commitment they rejected. Thus, in 1921, a group of Dadaist artists –including George Grosz, Otto Dix, Rudolf Schlichter, Hanna Höch, etc.– presented themselves as “Opposition to the November Group”, writing an Open Letter to this. The term New Objectivity was coined by the critic Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub for the exhibition New Objectivity. German painting from expressionism, held in 1925 at the Kunsthalle in Mannheim. In the words of Hartlaub: "the objective is to overcome the aesthetic pettiness of the form through a new objectivity born of disgust towards the bourgeois society of exploitation".

In parallel to the New Objectivity, the so-called “magical realism” arose, a name also proposed by Hartlaub in 1922 but disseminated above all by Franz Roh in his book Post-Expressionism. Magic Realism (1925). Magical realism was located further to the right of the New Objectivity – although it was equally eliminated by the Nazis – and represented a more personal and subjective line than the group of Grosz and Dix. Faced with the violence and drama of their contemporary objectives, the magical realists produced a calmer and timeless work, more serene and evocative, transmitting a stillness that was intended to appease the spirits after the war. His style was close to that of Italian metaphysical painting, trying to capture the transcendence of objects beyond the visible world. Among its figures were Georg Schrimpf, Alexander Kanoldt, Anton Räderscheidt, Carl Grossberg and Georg Scholz.

The main exponents of the New Objectivity were:

- George Grosz: coming from Dadaism, he was interested in popular art. He showed from a young man in his work an intense dislike for life, which became after the war in indignation. In his work he analyzed the society of his time coldly and methodically, demystifying the ruling classes to show their most cruel and despotic side. He carried especially against the army, the bourgeoisie and the clergy, in series like The face of the ruling class (1921) or Ecce Homo (1927), in scenes where violence and sex predominate. His characters are often mutilated by war, murderers, suicides, rich bourgeois and pigs, prostitutes, tramps, etc., in spitting figures, silhouetted in few strokes, such as dolls. Technically, it used resources from other styles, such as the geometry space of the cubism or the capture of the movement of the futurism.

- Otto Dix: Initiated in traditional realism, with influence of Hodler, Cranach and Durer, in Dix the social, pathetic, direct and macabre theme of the New Objectivity was emphasized by the realistic and thorough representation, almost diaphanous, of its urban scenes, populated by the same kind of characters portrayed Grosz: murderers, crippled, prostitutes, bourgeois. He exposed in a cold and methodical way the horrors of war, the butchers and massacres he witnessed as a soldier: thus, in the series The War (1924), he was inspired by the work of Goya and Callot.

- Max Beckmann: of academic formation and beginnings close to impressionism, the horror of war led him as his companions to crudely portray the reality that enveloped him. He then coined the influence of former teachers such as Grünewald, Brueghel and El Bosco, together with new contributions such as Cubism, from which he took his concept of space, which becomes in his work an exhausting, almost claustrophobic space, where the figures have an aspect of sculptural solidity, with very narrow outlines. In his series Hell (1919) made a dramatic portrait of post-war Berlin, with scenes of great violence, with tortured characters, screaming and reverberating in pain.

- Conrad Felixmüller: fierce opponent of the war, during the contest he assumed art as a form of political commitment. Linked to the circle of Pfemfert, editor of the magazine Die Aktion, moved in the anti-militarist atmosphere of Berlin, which rejected aestheticism in art, defending a committed art and social purpose. Influenced by the colorful Die Brücke and by the cubist decomposition, he simplified the space to angular and quadrilateral forms, which he called “synthetic coating”. Its theme focused on workers and the most disadvantaged social classes, with a strong component of denunciation.

- Christian Schad: a member of the Dadaist group of Zurich (1915-1920), where he worked with photographic paper – his “schadographs”–, later dedicated himself to the portrait, in cold and dispassionate portraits, strictly objectives, almost dehumanized, studying with a sober and scientific look to the characters he portrays, who are reduced to simple objects, alone and isolated, without the ability to communicate.

- Ludwig Meidner: member of the group Die Pathetiker (The Pathetics) together with Jakob Steinhardt and Richard Janthur, his main theme was the city, the urban landscape, which showed in scenes abyss, without space, with large crowds of people and agulous buildings of precarious balance, in an oppressive, anguish atmosphere. In his series Apocalyptic landscapes (1912-1920) brought back destroyed cities, which burn or explode, in panoramic views that more coldly show the horror of war.

- Karl Hofer: initiated in a certain classicism close to Hans von Marées, studied in Rome and Paris, where he was surprised by the war and was made prisoner for three years, a fact that deeply marked the development of his work, with tormented figures, of vacillating gestures, in static attitude, framed in clear designs, of cold colors and pristine and impersonal pincelada. His figures are solitary, thoughtful, melancholic, denouncing the hypocrisy and madness of modern life (The couple1925; Men with torches1925; The black room, 1930).

Other artists

Some artists did not belong to any group, personally developing a strongly intuitive expressionism, of various tendencies and styles:

- Paula Modersohn-Becker: he studied in Bremen and Hamburg, subsequently settled in the colony of artists of Worpswede (1897), then framed in a landscape near the Barbizon School. However, his interest in Rembrandt and medieval German painters led him to the search for more expressive art. Influenced by post-impressionism, as well as by Nietzsche and Rilke, he began to use in his works colors and shapes applied symbolically. In a visit to Paris between 1900 and 1906 he received the influence of Cézanne, Gauguin and Maillol, combining in a personal way the three-dimensional forms of Cézanne and the linear designs of Gauguin, mainly in portraits and maternal scenes, as well as nudes, evocators of a new conception in the relationship of the body with nature.

- Lovis Corinth: formed in impressionism – from which he was one of the main figures in Germany together with Max Liebermann and Max Slevogt–, led to his maturity towards expressionism with a series of works of psychological introspection, with a theme focused on erotic and macabre. After a stroke he suffered in 1911 and paralyzed his right hand, he learned to paint with the left. While he continued to anchor in optical printing as a method of creating his works, he gained a growing role in expressiveness, culminating in The Red Christ (1922), religious scene of remarkable anguish close to the visions of Nolde.

- Christian Rohlfs: of academic formation, was mainly dedicated to the landscape of realistic style, until it led to expressionism almost fifty years old. The determining fact for change could be his hiring in 1901 as a school-museum teacher Folkwang from Hagen, where he was able to contact the best works of international modern art. Thus, from 1902 he began to apply the color more systematically, in the puntilistic way, with a very bright colour. He later received the influence of Van Gogh, with landscapes of rhythmic and pasture, in undulating strips, without depth. Finally, after an exhibition Die Brücke in the Folkwang In 1907, he tried new techniques, such as xilography and linoleum, with accentuated black outlines. Its theme was varied, but focused on biblical themes and Nordic mythology.

- Wilhelm Morgner: student of Georg Tappert, a painter linked to the colony of Worpswede, whose lyric landscape influenced him in the first place, later evolved into a more personal and expressive style, influenced by the morphic cubism, where the color lines are important, with pointed brushstrokes that juxtapone form something like a tap. By accentuating the color and the line dropped out of the depth, in flat compositions where the objects are placed in parallel, and the figures usually represent themselves as a profile. Since 1912, the religious theme, in almost abstract compositions, was important in his work, with simple lines drawn with colour.

The Vienna Group

In Austria, the expressionists were influenced by German (Jugendstil) and Austrian (Sezession) modernism, as well as by the symbolists Gustav Klimt and Ferdinand Hodler. Austrian expressionism stood out for the tension of the graphic composition, distorting reality subjectively, with a theme that was mainly erotic –represented by Schiele– or psychological –represented by Kokoschka–. In contrast to impressionism and the preponderant nineteenth-century academic art in the Austria at the turn of the century, young Austrian artists followed in the footsteps of Klimt in search of greater expressiveness, reflecting in their works an existential theme with a great philosophical and psychological background, focused on life and death, illness and pain, sex and love.

Its main representatives were Egon Schiele, Oskar Kokoschka, Richard Gerstl, Max Oppenheimer, Albert Paris von Gütersloh and Herbert Boeckl, as well as Alfred Kubin, a member of Der Blaue Reiter. It is worth noting mainly the work of two artists:

- Egon Schiele: disciple of Klimt, his work revolved around a theme based on sexuality, solitude and incommunicado, with a certain air of voyeurism, with very explicit works by which he was even imprisoned, accused of pornography. Dedicated mainly to drawing, he gave an essential role to the line, with which he based his compositions, with stylized figures immersed in an oppressive, tense space. He claimed a repetitive human typology, with an elongated, schematic canon, removed from naturalism, with vivid colors, exalted, highlighting the linear character, the outline.

- Oskar Kokoschka: received the influence of Van Gogh and the classic past, mainly the Baroque (Rembrandt) and the Venetian school (Tintoretto, Veronese). He was also linked to the figure of Klimt, as well as the architect Adolf Loos. However, he created his own personal, visionary and tormented style, in compositions where space gains great prominence, a dense, sinuous space, where the figures are submerged, which float in it immersed in a centrifugal current that produces a spiral movement. His theme used to be love, sexuality and death, sometimes dedicating itself to portrait and landscape. His first works had a medieval and symbolic style close to the Nabis Or Picasso's blue era. Since 1906, in which he met Van Gogh's work, he began in a type of psychological court portrait, which sought to reflect the emotional imbalance of the portrayed, with the supremacy of the line over colour. His most purely expressionist works stand out by the twisted figures, tortured expression and romantic passion, as well as The wife of the wind (1914). Since the 1920s he devoted himself more to the landscape, with a certain baroque look, lighter stroke and brighter colors.

School of Paris

The School of Paris is called a heterodox group of artists who worked in Paris in the interwar period (1905-1940), linked to various artistic styles such as post-impressionism, expressionism, cubism and surrealism. The term encompasses a wide variety of artists, both French and foreign, who resided in the French capital between the two world wars. At that time, the city of the Seine was a fertile center of artistic creation and dissemination, both because of its political, cultural and economic environment, and because it was the origin of various avant-garde movements such as Fauvism and Cubism, and the place of residence of great masters like Picasso, Braque, Matisse, Léger, etc. It was also a remarkable center for collecting and art galleries. Most of the artists lived in the Montmartre and Montparnasse neighborhoods, and were characterized by their miserable and bohemian life.

In the School of Paris there was great stylistic diversity, although most were linked to a greater or lesser extent to expressionism, although interpreted in a personal and heterodox way: artists such as Amedeo Modigliani, Chaïm Soutine, Jules Pascin and Maurice Utrillo They were known as “les maudits” (the damned), for their bohemian and tortured art, a reflection of a night owl, miserable and desperate atmosphere. On the other hand, Marc Chagall represents a more vital, dynamic and colorful expressionism, synthesizing his native Russian iconography with Fauvist color and cubist space.

The most prominent members of the school were: