Exodus

The Exodus is the second book of the Bible. This is a traditional text that narrates the story of the exodus in which the Israelites leave slavery in Egypt by the force of Yahveh (chapters 1-12). Describe how God sends the ten plagues of Egypt so that Pharaoh will free the Israelites. The Israelites then travel with the prophet Moses to Mount Sinai (chapters 13-18), where Yahweh promises them the land of Canaan (the Promised Land) in exchange for his allegiance. There, they enter into a Mosaic covenant with Yahveh, and the drafting of the Ten Commandments and other legal norms (chaps. 19-24). The instructions for building the Tabernacle, the means by which he will come from heaven and dwell with them and lead them in a holy war to possess the land, and then give them peace (chs. 25-31). The episode of the golden calf, where the law is given for the second time (chaps. 32-34). And finally, more about the construction of the tabernacle, the priest's clothing and other ritual objects (chapters 35-40).

In Judaism, the book of Exodus is part of the canon, being contained in the Torah and forming one of the five books of the Pentateuch, which make up the first part of the Hebrew Bible. In Christianity, the book of Exodus it is also part of the canon and is found in the Old Testament.

Exodus was traditionally attributed to Moses himself, but modern scholars view its final composition as a product of the Babylonian exile (6th century BCE), based on earlier written and oral traditions. The consensus among scholars holds that the Exodus as it appears in the Bible is legendary and does not accurately describe historical events, although a simple majority maintains the existence of a historical core that gave substance to the later biblical tradition.

Name

Exodus comes from the Latin exŏdus, and this from the Greek ἔξοδος, exodos, which means 'exit'.

In Judaism, the traditional text is known in Hebrew as Shemot (שׁמות), a term whose literal meaning is 'names'.

It is in the Septuagint that it is titled Exodus. When the translation into Latin was carried out, said name was adopted, which was then expressed as exŏdus. The different spelling transformations, necessary according to each language, gave rise, in Spanish, to the term "Éxodo".

Purpose

The main purpose of Exodus is to keep alive in the memory of the Hebrew people the founding story of this group as a nation, after leaving Egypt, once free and heading towards the Promised Land, the Israelite people became aware of their ethnic, philosophical, religious and national unity for the first time, given that the Book of Exodus refers to the slavery of the Hebrews in Egypt and the epic that led to their liberation from such a condition, making them a free group, with its own national identity and in turn provided with Law. Significant, in this context was what Moses said to the Israelite people:

« Be mindful of this day, in which ye came out of Egypt, out of the house of bondage, for Yahweh has brought you out of here with a strong hand; therefore ye shall not eat leudate. You leave today in the month of Abib. [...] You'll do this celebration this month. Seven days you will eat unleavened bread, and the seventh day will be a feast for Yahweh. For the seven days the unleavened bread shall be eaten, and no leaven shall be seen with thee, nor leaven. And thou shalt tell thy son in that day, saying, This is done for what the LORD did to me when he brought me out of Egypt. And it shall be to thee as a sign upon thy hand, and as a memorial before thine eyes, that the law of the LORD may be in thine mouth: for Yahweh brought thee out of Egypt with a strong hand. Therefore, you will keep this rite in its time of year in year ». Exodus 13:3-10.

Based on the aforementioned biblical passage, the people of Israel have considered —and still consider— their obligation to narrate the story of the Exodus throughout each paschal celebration. This takes place every Pesach Seder, when the people of Israel reads and remembers the contents that are expressed in the Paschal Haggadah.

The Book of Exodus also establishes the bases of the liturgy and worship of the people of Israel; the book in question is in turn dominated in its entirety by the figure of the patriarch Moses, who served as leader, conductor and legislator of the people of Israel.

The Book of Exodus is not exclusively narrative, but also contains laws, hymns, and prayers.

Structure

"The story begins with a people enslaved in the midst of Egyptian idolatry and ends with a redeemed people dwelling in the presence of God".

1. Oppression in Egypt 1,1-11,10

- Slavery in Egypt 1,1-22

- Preparation of Liberator 2,1-4,31

- Fight against the oppressor 5.1-11.10

2. Liberator of Egypt 12,1-14,31

- Blood Redemption 12.1-51

- Institution of the Passover 12.1-28

- The tenth plague, the death of the firstborn 12,29-51

- Redemption by powerful divine help 13,1-14,31

- Consecration of the firstborn 13,1-16

- Red Sea Cross 13,17- 14,31

3. Education of the redeemed in the desert 15,1-18,27

- Successful song of the redeemed 15.1-21

- Rescues tested 15,22-17,16

- bitter test 15,22-27

- Hunger 16.1-36

- Sed 17,1-7

- Conflict 17.8-16

- Government of the redeemed 18.1-27

4. “Consecration of the Redeemed on Sinai” 19,1-34-35

- Acceptance of Law 19.1-31.18

- Directives given to Moses 19.1-25

- Commandments of a moral character 20.1-26

- Social ordinances 21,1-24,11

- Rules of religious character 24,12-31-18

- Infraction of Law 32.1-14

- The golden calf 32.1-14

- Breaking tables 32,15-35

- Restoration of Law 33.1-34.35

- Vision renewed 33,1-34,35

- The second tables 34.1-35

5. The worship of the redeemed in the tabernacle, priesthood and ritual 38,1-40,38

- Offers and workers for the tabernacle 35,1-40,38

- Construction of the tabernacle and appointment of participants 36.1-39.43

- He erects the tabernacle and descends the divine glory 40:1-38

Summary

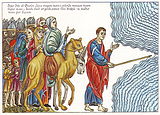

Jacob's sons join their brother Joseph in Egypt with their families, where their people begin to grow in number. Four hundred years later, the new Pharaoh of Egypt, who does not remember how Joseph had saved Egypt from famine, fears that the Israelites may become a fifth column. He forces them into slavery and orders all newborn children to be thrown into the Nile, to reduce the population. A Levite woman (Jochabed, according to other sources) saves the baby from her by setting it adrift on the Nile River in a reed ark. Pharaoh's daughter finds the boy, names him Moses, and out of sympathy for the Hebrew boy, she raises him as her own. Aware of his origins, an adult Moses kills an Egyptian overseer who beats a Hebrew slave and flees to Midian to escape punishment. There he marries Zipporah, daughter of a Midianite priest Jethro, and suddenly meets God in a burning bush. Moses asks God for his name, to which God answers "I am who I am", the book's explanation of the origin of the name Yahweh, as God is known from then on. God tells Moses to return to Egypt and lead the Hebrews to Canaan, the land promised to Abraham in the Book of Genesis. On the return trip to Egypt, God tries to kill Moses for not having circumcised his son, but Zipporah saves his life.

Moses reunites with his brother Aaron and, back in Egypt, summons the Israelite elders, preparing them to go into the desert to worship God at a spring festival. Pharaoh refuses to release the Israelites from their work for the festival, so God curses the Egyptians with ten terrible plagues, including a river of blood, a plague of frogs, and thick darkness. Moses is commanded by God to set the first month of Aviv at the head of the Hebrew calendar, and commands the Israelites to take a lamb on the 10th of the month, slaughter the lamb on the 14th, smear its blood on their mezuzahs and lintels., and celebrate Easter that night, during the full moon. The tenth plague arrives that night, causing the death of all the Egyptian firstborn, and prompting Pharaoh to order a final pursuit of the Israelites across the Red Sea as they escape from Egypt. God assists the Israelite exodus by parting the sea and allowing the Israelites to pass through, before drowning Pharaoh's forces.

Because life in the desert is arduous, the Israelites complain and long for Egypt, but God miraculously provides them with manna to eat and water to drink. The Israelites arrive at the mountain of God, where Moses' father-in-law, Jethro, visits Moses; at his suggestion, Moses appoints judges over Israel. God asks them if they agree to be his people. They accept. The people gather at the foot of the mountain, and with thunder and lightning, fire and clouds of smoke, the sound of trumpets and the shaking of the mountain, God appears on top, and the people see the cloud and hear the voice (or possibly the sound) of God. God tells Moses to go up the mountain. God pronounces the Ten Commandments in full view of all Israel. Moses goes up the mountain into the presence of God, who pronounces the Covenant Code of ritual and civil law and promises them Canaan if they obey. Moses comes down from the mountain and writes God's words, and the people agree to keep them. God calls Moses up the mountain again, where he remains for forty days and nights, at the end of which he returns carrying the set of stone tablets.

God gives Moses instructions for the construction of the tabernacle so that God can permanently dwell among his chosen people, along with instructions for the priestly garments, the altar and its accessories, procedures for the ordination of priests, and daily offerings of sacrifice. Aaron becomes the first hereditary priest. God gives Moses the two stone tablets containing the words of the ten commandments, written with the "finger of God."

While Moses is with God, Aaron throws down a golden calf, which the people worship. God informs Moses of his apostasy and threatens to kill them all, but relents when Moses pleads for them. Moses comes down from the mountain, breaks the stone tablets in a rage, and orders the Levites to slaughter the faithless Israelites. God commands Moses to build two new tablets. Moses ascends the mountain again, where God dictates the Ten Commandments to write on the tablets.

Moses descends from the mountain with a changed face; from then on he must hide his face with a veil. Moses gathers the Hebrews and repeats to them the commandments that he has received from God, which are to keep the Sabbath and build the Tabernacle. The Israelites do as they are told. From that moment God lives in the Tabernacle and orders the travels of the Hebrews.

Theme

| Chapter | Items | |

| 1-2 | Slavery | |

| 14 | Persecution | |

| 8-9-10-11 | “The Judgments of God” | |

| 4- | Fe | |

| 6-16-17-23(v20)-33-34 | “Promises of God” | |

| 12-20 to 25-35 | “Mandatos of God” | |

| 34(v27). | “Communion with God” | |

| 3(v5) and 36(v8) | Holy Place |

Symbols

| Chapter | Symbol | |

| 1(v14). | Bar | |

| 14 | Blue | |

| 9(v32). | Trigo | |

| 30(v17)- | Bronze | |

| 12(v7). | Blood | |

| 16(v13). | Mana | |

| 34(v27). | Gold | |

| 25(v10). | Ark | |

| 26(v32). | Acacia Wood | |

| 36(v8). | Tabernacle | |

| 34(v1). | Stone Tables |

Authorship

Mosaic authorship. Traditionally, both Jews and Christians ascribe the book of Exodus, as well as all the other books of the Pentateuch, to Moses.

Documentary hypothesis. According to the so-called documentary hypothesis, the main authors of this work would have been the groups of the Yavist, Elohist, Priestly and Deuteronomist tradition. The documentary hypothesis estimates that the poetic Song of the Sea and the Code of the Pact (written in prose) are originally independent works by authors but somehow associated with the aforementioned groups. In this hypothesis, the Elohists are identified as the only ones responsible for the episode of the golden calf, and the priestly tradition is the author of the instructions for creating the tabernacle, the clothing and ritual objects, as well as the description of their creation. Three traditional authors or teams of writers are in turn also authors of each one of the parts of the law code, the Elohist tradition, of the Covenant; the priestly, of the ethical decalogue; and the yavista, from the decalogue of rituals. The documentary hypothesis holds that the other parts of the book of Exodus emerged from intermingled versions of the Yawist, Elohist, and priestly tradition. The reconstruction of the stories in those sources, applying this hypothesis, tends to identify differences and variations between different narrative segments.

Historicity

The traditional story presented in the book of Exodus is known to Jews to this day in terms of paschal legend, during the Jewish Passover celebration the Haggadah (הגדה "story") of Pesach is read. For many it is a historical fact that they commemorate.

Even so, the possible historicity of the event has given rise to different speculative theories. One of them, for example, maintains that the Hebrews would not have been released but would have been expelled from Egypt. According to this theory, the issue in question would be linked to the expulsion of the Hyksos, an event described in Egyptian literature.

The situation is further complicated by the fact that the Hebrew tradition was initially and for several centuries an oral tradition, of which at the moment only written documents dating from the century are known VIII a. c.

There is also the so-called “two exodus hypothesis”. In the absence of archaeological evidence on the exodus of the Israelites, some researchers suppose that the Hebrew tradition could be based on fragments or remains of real events and raise the possibility that more than one expulsion of Semitic groups from Egypt in the direction of Canaan.

There are those who in turn suppose that the exodus could have taken place in the time of Amenhotep IV, who is also known as “Akhenaten”. Among them stands out Sigmund Freud, who expresses this conviction in his work Moses and Monotheism (1934-1939). Freud argues that the monotheistic connection between Akhenaten and Moses is suggestive and could well constitute a solution. for the enigma that emanates from the book of Exodus.

On the other hand, there are many other hypotheses about the subject, some contemplate migratory waves that could have given rise to not only one but several exoduses. Be that as it may, the "two exodus hypothesis" perhaps responds better than others to what happened in historical terms by suggesting different remains collected by the Hebrew oral tradition that, over time, were intermingled and finally merged, giving place to the narrative of the book of Exodus.

Exodus as a literary legend

In The Unearthed Bible, Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman argue that the Hebrew exodus did not exist. In 2006, Finkelstein asserted, "There was no exodus," arguing that under the microscope of archaeological investigations there is no evidence of the exodus; that decades of searches in Kadesh (Barnea) did not yield any absolute results, to which is added the complete non-existence of Egyptian evidence —which, according to him, were fabricated by “excellent chroniclers”—, and above all —Finkelstein maintains— because the archeology systematically contradicts the Bible on this issue, there is evidence that in Canaan, (the Promised Land), there were already proto-Israeli settlements long before the possible dates of the Exodus from Egypt. In other words, Finkelstein proposes that there was no conquest led by the Israelite warrior Joshua, but that Canaan was peacefully invaded several centuries before Joshua by proto-Hebrew foreign nomads at the time of the decline of the Canaanite city-states.

Exodus as a historical fact

Different points of view have been raised regarding the historicity of the Exodus considering the lack of records, archaeological evidence and many other factors. Different criticisms and speculative theories that differ from the original biblical account also originated. One of the theories that were raised had to do with the tremendous Egyptian military presence that followed the coastal route of the Mediterranean to Canaan. This theory was discarded because it did not agree with what was reported in the Bible, since in the text it was indicates that the Hebrews did not follow the Mediterranean route, lest they back down when they saw the army (Exodus 13:17-18).

Another criticism that is often made is the lack of Egyptian records about the event, although it is possible that the Egyptians had a written document about it; the British Egyptologist Kenneth Kitchen stated before this fact that the huge papyrus archives that were stored in ancient Egypt are missing:

In the fan of the Nile delta, filled with water, there is no papyrus that survives (tell or not the fugitive Hebrews)... In other words, since the official files of the s. XIII B.C. from cities located in the eastern part of the Nile delta have been lost to one hundred percent, we cannot expect them to contain mentions of the Hebrews or of any other people.Kenneth Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament

Dating

Data provided by the Biblical story

According to the biblical book of Genesis, the family of the patriarch Jacob left the valley of Beersheba in Canaan (Gen 46,5) and under the protection of Joseph, son of the Hebrew patriarch Jacob and prime minister in Egypt, the Hebrews They settled in the valley of Goshen, in the region called Rameses (Gen 47,6), and there they multiplied. Joseph died at the age of one hundred and ten years (Gen,50,26), the slavery of the Hebrews in the Old Egypt began some time later, more in a still undetermined period.

The Egyptian city from which the Israelites leave in Exodus is also called Rameses, and according to Biblical tradition, there were about 600,000 males (not counting women, children and the elderly, nor non-Hebrews). who accompanied them). Rameses could be the current Qantir in Lower Egypt, in the land of Gosen, where Jacob's family came to live under the protection of Joseph and where the Hebrews multiplied in those times (Gen, 47,1). From Sukkot, the Hebrews and those who accompanied them went out to Etam, at the entrance to the desert (Exodus, 13,20) and went to camp at Pi-hahirot, "between Migdol and the Sea of reeds (Yam Zuf, Red Sea) towards Baal-Zephon".

In Genesis 15,13 there is a story in which God tells Abraham that his descendants will dwell in a foreign land, and that a foreign nation would afflict them, this for a period of 400 years. According to the wording of this passage, such 400 years can refer both to the experience of being an outsider and to the period of slavery that began long after the death of Joseph in Egypt. In Exodus 12,40 it is indicated that the exact 430 years of the "dwelling of the children of Israel in Egypt" the same day that the Hebrew people were freed through Moses.

In Galatians 3,17 the author of the epistle points out that the Law came into existence 430 years after God made a covenant with Abraham and his descendants, which seems to imply a point of view in which the 430 years include Abraham's dwelling in Canaan. This view existed in the I century d. C. the Septuagint translated this passage, “But the dwelling of the children of Israel that they (the Alexandrian codex, 5th c. AD, adds "and their fathers dwelt") in the land of Egypt and in the land of Canaan was four hundred and thirty years long. The Samaritan Pentateuch also says, "in the land of Canaan and in the land of Egypt." Similarly, Josephus wrote in Jewish Antiquities, Book II, chapter 15, para. 2, "They came out of Egypt in the month of Xantichus (the Macedonian month that Josephus equated with the month of Nisan),... four hundred and thirty years after the arrival of our ancestor Abram in Canaan." (Complete works of Flavio Josefo, by L. Farré, 1961, volume 1, p. 168.) Thus, according to this opinion present in the century I the 430 years are counted from the time Abraham crossed the Euphrates on his way to Canaan until the time the Israelites left Egypt.

Later in the Bible it is explained that Solomon's Temple was built around 480 years after the departure from Egypt (1Kings 6:1).

Hypotheses based on Egyptian history

The dating of the chronological composition of the book of Exodus is difficult and, to reach a reasonable certainty, it is necessary to relate the events in it with the history of Ancient Egypt.

There have been many attempts to adjust the dates of the events in this book to make them more accurate according to the Gregorian calendar. These attempts rarely take into account the following considerations,

- the intricate chronological relations corresponding to the Hebrew calendar, which is luni-solar and possesses its own criteria, which in fact are neither necessarily coincidental nor easily adaptable to those solars that govern both the Egyptian and the Gregorian;

- the name or identity of the pharaoh of that time, given that in the Book of Exodus it is called merely "faraon";

- the dates of non-biblical descriptions of the different seminal peoples who may have left Egypt;

- or the date that archaeologists and historians establish for the destruction of Jericho.

But, in general, one tends to assume that a correct identification of the Pharaoh mentioned in Exodus would be the key to establishing the proper chronology for Exodus. Some, however, question the archaeological evidence supporting the date of the Exodus and the date of the conquest of Canaan, but the earliest known settlements of Israelites do not appear until 1230 B.C. C., long after the walls of Jericho were destroyed, in addition to the lack of evidence of an Exodus of such magnitude, and the absence of evidence of a settlement in the Sinai or Arabian desert. There is also no evidence of the military conquest of Canaan.

Yet various pharaohs and dynasties have been proposed for the Exodus, covering such possibilities up to two centuries apart,

- Amosis I (1550-1525 BC), falling into the centuryXVIa. C. and has the support of the semitic in times of the hicsos coinciding with the period of the expulsion of the Hicsos, although this contradicts some key aspects narrated in the Bible. This link between the Israelites and the Hicsos was already proposed by Flavio Josefo in the centuryId. C.

- Tutmosis I (death without male offspring in 1492 B.C.), Tutmosis III or Amenhotep II of the 18th Dynasty - 15th century B.C. It has also been considered that century by authors such as Hans Goedicke, egyptologist at Johns Hopkins University, who believes that the plagues of Egypt may have coincided with the eruption of the island of Tera (Santorini) in 1477 a. C.

- Ramses II or Merenptah of the 19th Dynasty—1279-1213 B.C.— There are those who believe this hypothesis is consistent with recent archaeological discoveries in Tell el-Daba and Jericho. This hypothesis is based mainly on the name of the storage city that the Israelites were forced to build, one of which was called Ramses, and together with Pitom are located in the times of Ramses II. The city or town in which the Israelites lived in the Nile delta is also called Ramess, (Exodus 12,37, “The children of Israel from Ramess to Succoth, about six hundred thousand footmen, without counting the children...” Numbers 33,3, “Of Ramesses came out in the first month, 15 days of the first month...” Numbers 33,5, “Then the children of Israel of Ramess went out and camped in Succoth.”

If the latter hypothesis is accepted, the initial oppressive pharaoh would have been Seti I, whose rule took place between 1294 and 1279 BC. C., and the Exodus would have developed during the reign of Ramses II (who ruled Egypt between 1279 and 1213 BC), considering in terms of research the year 1250 BC. C.

Calculating the date of the beginning of the Exodus

The Bible does not mention the pharaoh of the Exodus by name, nor does it give an exact date to the Exodus. In 1Kings 6: 1 it is read that King Solomon began to build the temple in Jerusalem in the fourth year of his reign, «480 years after the children of Israel left Of Egipt". The fall of Jerusalem to the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II occurred in approximately 586 B.C. The period of the kings of Israel and Judah is difficult to determine, but from the parallel account of the First and Second Book of Kings it appears that 390 years elapsed until the death of King Solomon; and an additional 37 years spanned by Solomon's rule (including the fourth year of his rule), would give the date 1013 B.C. C. for the construction of the first Temple of Jerusalem, from which it can be deduced that 480 years before would imply that the date of the Exodus would have been in the year 1493 a. C. (or 1513 B.C., if the fall of Jerusalem is dated to 607 B.C., taking literally the 70-year duration of the Babylonian exile and desolation of the country mentioned in 2 Chronicles 36,21; Jeremiah 25,11; 29,10; Zechariah 7,5 and Daniel 9,2).

However, considering the complicated chronology of the kings of Judah and Israel, Enciclopedia Judaica Castellana states that,

For the absolute fixation of the dates is available the solar eclipse of the eponymous Isid-Seti-Igbi, which occurred on 13 June 809 BC, that is 91 years after the battle of Cancor, in Ajab life, and 78 years after the shipment, by Yehu, of tributes to Salmanasar III of Nineveh. The eponymous tablets and the Babylonian chronicle place the fall of Samaria in January of 721 BC. The two eclipses of the 7th year of Changes (523-522 B.C.) set the date of the advent of Nebuchadnezzar in May or June of the 605 B.C., and that of the release of Joachim by Evilmerodac, son of that, on the 25th or 27th of adar, that is Sunday, February 29th or Tuesday, March 2, 561 B.

It follows that the fourth year of Solomon's reign should have been 967 B.C. C. Therefore, the date of Exodus was 1447 B.C. C. (967 + 480), when Thutmosis III or Amenhotep II ruled, although at the moment any type of document or archaeological remains that confirms such an event is unknown.

From the level of belief, Orthodox Judaism, for its part, locates the beginning of the Exodus of the people of Israel on Nisan 15, 2448, a date that corresponds in the Gregorian calendar to the year 1313 BC. C.

Since the Bible indicates that the Hebrews left the city called Rameses for Sukkot, cities that are dated to the 13th century a. C.., during the period in which Ramses II ruled Egypt, in the field of research the year 1250 B.C. is considered H.W.F. Saggs observes in his academic writings that,

The mention of the city of Ramess in Exodus 1:11 as a place of storage, built in part by the Israeli slaves, actually offers a chronological indication, since [today] it is known that Ramses II built a city, Per-Ramsés [i.e., Pi-Ramsés], which corresponds to the name provided by the Bible. This tends to place slavery [of the Hebrews] in Egypt and its departure from that country in the 13th century BC.

Route undertaken, according to the biblical story

The biblical account states that, after crossing the Red Sea, the Hebrews entered the desert of Shur or Etam, and three days later they reached Mara. In this place, the unity of the Hebrew people began to suffer and there were those who murmured and, despite the facts they had seen from God, they opposed Moses (Exodus, 15,24).

From Mara they moved to Elim, an oasis of twelve water sources, from this place they entered the desert of Sin in the direction of Mount Sinai bordering the Red Sea; Two months had already passed since the departure from Egypt. Here the event of the manna provided by God is verified.

Already in the desert of Sin, the congregation moved from locations such as Dofca and Alús. In Rephidim ―near Mount Horeb, in the desert of Paran, a place without water― they fought for the first time as a people against the Amalekites, defeating them (Exodus, 17,13). At this place, Moses struck a rock with his staff and made drinkable water gush out.

From Rephidim, the Hebrew people entered the Sinai desert and camped at the end of the Mount Sinai or Mount Horeb 90 days after leaving Egypt. In this place, Moses was able to see Yahweh, who gave him the Ten Commandments. He also constituted the priesthood of Aaron (or Levitical priesthood), the first civil and religious laws in the Jewish people, additionally the first Tabernacle, the Ark of the Covenant, was built. (Exodus, 25,10). In this place they remained two years and two months. Upon leaving Sinai, the people of Israel were governed in all legal, civil, moral and religious aspects (Exodus, 10,11).

From Sinai they left for the desert of Paran and lived in Kibrot-hataava (Exodus, 11,35) to move to Hazerot, in the middle of the desert. From this place, Moses assigned twelve spies to reconnoitre the land of Canaan (Exodus, 13) from Mount Negev (in the desert of the same name). Meanwhile, the congregation advanced to Ritma and from there to Rimón-Peres.

The recognized land of Canaan was inhabited by Jebusites, Anakites, Amalekites, Amorites, and Canaanites.

The information obtained in forty days was poorly received by the congregation, since ten of the twelve spies incited murmurings against their leaders, which caused a disastrous rebellion among the people against Yahweh because they thought that God was putting them to death before people apparently more powerful than the Israelites themselves (Numbers 14) and many fought to return to Egypt.

Yahweh cursed the ten spies, who died of the plague (Numbers, 14,36) and also condemned the people of Israel to be lost for forty years in the Negev desert. Only Caleb and Joshua were authorized to leave the desert and enter Canaan (Numbers 14,30). Israel tries to rebel against the condemnation in the desert but they are defeated by the Amorites led by the king of Edom and they are forced to remain between Kadesh, the desert of Moab and the Negev and they remain there for almost 40 years. Aaron dies on Mount Hor (Numbers, 20,22-29).

When the 40 years were up, and the entire adult generation had died, the next generation was finally able to enter Canaan with Joshua as their leader (Deuteronomy, 2,14 -24). Yahweh did not authorize Moses to enter Canaan and only allowed him to observe the land of inheritance from Mount Pisgah or Nebo (Deuteronomy, 3,27 and Deuteronomy, 32, 48-52) to die in this same place and be buried in Moab.

Religious meaning

Judaism

The departure from Egypt and the revelation on Mount Sinai are two foundational events in the history of the people of Israel. Significantly, both are narrated in the Biblical book of Exodus. According to Judaism, the miracle of the liberation of the Hebrew people demonstrates and confirms the people of Israel as the people chosen by Yahveh and said liberation is in turn decisive in the establishment of the Yahwist liturgy.

Christianity

For Christians, the celebration of the first Easter paves the way for the Christian resurrection. The formation of the People of God is the antecedent of the Church as an assembly and gathering of the faithful through the liturgy.

The New Testament reinterprets many of the events of Exodus, Paul of Tarsus insists on this in a special way (1st Corinthians, 10,2-4), and then he compares the passage of the Red Sea with baptism and the Eucharist (1st Corinthians, 79,8). In the Gospel of John the messiah Jesus Christ is compared to Moses, and Christ opposes manna to the “bread of life”. On more than one occasion, the parallelism of the structure of Exodus with this gospel has been noted, especially in the first chapters.

Finally, in the Epistle to the Hebrews death is conceived as the exodus of life to the Promised Land of Heaven, the Christian priesthood as the Hebrew, the sacrifice of Christ as that of the Sinai and the old alliance as the new, is sacramented with the blood of Jesus.

The book of Exodus in the collective imagination

Contenido relacionado

Selknam

Jesus company

Pella (Greece)

![Hebreos en esclavitud en Egipto. Hagadá Barcelona, arte sefardí, 1350, fol. 30v. Inscripción en hebreo: "Esclavos fuimos de Faraón en Egipto."[35]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1a/Barcelona_Haggadah_30v.jpg/121px-Barcelona_Haggadah_30v.jpg)

![Los hebreos recogiendo el maná en el desierto. Boceto de Tiépolo, 1740.[36]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/30/Giovanni_Battista_Tiepolo_-_Los_hebreos_recogiendo_el_man%C3%A1_en_el_desierto_%28boceto%29_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg/116px-Giovanni_Battista_Tiepolo_-_Los_hebreos_recogiendo_el_man%C3%A1_en_el_desierto_%28boceto%29_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

![La adoración del becerro de oro. Óleo de Poussin, 1634.[37]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/16/Nicolas_Poussin_-_The_Adoration_of_the_Golden_Calf_-_WGA18293.jpg/160px-Nicolas_Poussin_-_The_Adoration_of_the_Golden_Calf_-_WGA18293.jpg)