Existentialism

Existentialism is a philosophical current and, later, a literary vanguard oriented around human existence itself through the analysis of the human condition, freedom, individual responsibility, emotions, as well as the meaning of life. He maintains that existence precedes essence and that reality is prior to thought and will to intelligence. He argues that the starting point of philosophical thought must be the individual and phenomenological subjective experiences, as well as the "angst” or the existential anguish generated by the apparent absurdity of the world. On this basis, existentialists argue that the combination of moral thought and scientific thought are insufficient to understand human existence, therefore an additional set of categories is necessary, governed by the norm of authenticity. A primary virtue in existentialist thought is authenticity. Existentialism would influence many disciplines outside of philosophy, including theology, theater, art, literature, and psychology, Kierkegaard (founder of this current) and Nietzsche laid the foundations of existentialist philosophy.

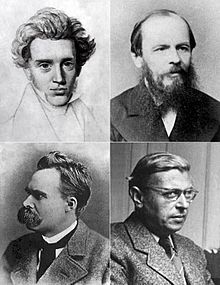

It is not a homogeneous or unified philosophical school, nor is it a systematized one, and its followers are characterized mainly by their reactions against traditional philosophy. Three types of existentialist philosophical "schools" are considered:

- Christian Existentialism: Blaise Pascal and Fiódor Dostoyevski as “precursors” and Søren Kierkegaard, León Chestov and Gabriel Marcel as “existenceists”.

- Agnostic Existentialism: Karl Jaspers and Albert Camus.

- Existentialism atheist: Friedrich Nietzsche, Martin Heidegger, Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir.

In literature, the realist writer Dostoevsky (considered a forerunner of the movement), Hermann Hesse, Franz Kafka, Rainer Maria Rilke, Dino Buzzati, Thomas Mann, Cèline, Stanisław Lem, Albert Camus and the literature of the absurd and Emil Cioran. In literature in the Spanish language, Miguel de Unamuno (adhered to Christian existentialism), Juan Carlos Onetti and Ernesto Sabato stood out with their novel El túnel, which was admired by Mann and Camus.

Existentialism originated in the 19th century and lasted until approximately the second half of the 20th century.

Concept

There was never a general agreement on the definition of existentialism. The term is often seen as a historical convenience that was invented to describe many philosophers, in retrospect, long after they had died. In fact, although existentialism is generally considered to have originated with the work of Kierkegaard, it was Jean-Paul Sartre who was the first prominent philosopher to adopt the term to describe his own philosophy. Sartre proposes the idea that "all existentialists have in common the fundamental doctrine that existence precedes essence",, which means that the most important consideration for the person is the fact of being a conscious being that acts independently and responsibly: “the existence”, instead of being labeled with roles, stereotypes, definitions or other preconceived categories that fit the individual, “the essence”. The actual life of the person is (what constitutes) what might be called the "true essence" of him rather than being there attributed to an arbitrary essence that others use to define it.

According to the philosopher Steven Crowell, defining existentialism has been relatively difficult, and he argues that it is best understood as a general approach used to reject certain systematic philosophies, rather than as a systematic philosophy itself.

One of its fundamental postulates is that in the human being "existence precedes essence" (Sartre), that is, that there is no human nature that determines individuals, but rather their actions determine who they are. they are, as well as the meaning of their lives. Existentialism defends that the individual is free and totally responsible for his acts. This encourages in the human being the creation of an ethic of individual responsibility, separated from any external belief system.

In general terms, existentialism seeks an ethic that overcomes moralisms and prejudices; This, to the neophyte observer, may find it contradictory, since the ethics sought by existentialism is a universal ethics and valid for all human beings, which often does not coincide with the postulates of the various particular morals of each of the pre-existing cultures.

History

Some consider that existentialism per se spans the entire history of humanity (for example, in the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh one finds approaches full of anguish, hope, mourning, melancholy, longing for eternity, which later existentialism will always reiterate), since its themes are the capitals of each human being and of all humanity as a whole.

Existentialism has its antecedents in the 19th century in the thought of Søren Kierkegaard and Friedrich Nietzsche. Also, although less directly, in the pessimism of Arthur Schopenhauer, as well as in the novels of Fyodor Dostoyevski. In the XX century, among the most representative philosophers of existentialism are Lev Shestov, Martin Heidegger, Karl Jaspers, Jean-Paul Sartre, Miguel de Unamuno, Simone de Beauvoir, Gabriel Marcel and Albert Camus.

However, existentialism gets its name in the 20th century and, particularly, after the terribly traumatic experiences he lived through humanity during World War I and World War II. During these two conflicts (which could be described on the one hand as extreme cases of the stupidity that humanity can have and on the other - agreeing with Hannah Arendt - as the ways in which human violence reaches its apogee with the trivialization of wrong) the thinkers arose who later asked themselves: What meaning does life have?, for or why does being exist? And is there total freedom?

Development in the 20th century

Existentialism was born as a reaction against the prevailing philosophical traditions, such as rationalism or empiricism, which seek to discover a legitimate order within the structure of the observable world, where the universal meaning of things can be obtained. Between the 1940s and 1950s, French existentialists such as Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, and Simone de Beauvoir released academic or fictional writings that popularized existential themes such as freedom, nothingness, the absurd, among others. Walter Kaufmann described existentialism as "the refusal to belong to any school of thought, the repudiation of adherence to any body of beliefs, and especially the systematic ones, and a marked dissatisfaction with traditional philosophy, which he dismisses as superficial, academic, and remote." of the life".

Existentialism has been attributed an experiential character, linked to dilemmas, havoc, contradictions and human stupidity. This philosophical current discusses and proposes solutions to the problems more properly inherent to the human condition, such as the absurdity of living, the significance and insignificance of being, the dilemma in wars, the eternal theme of time, freedom, whether physical or metaphysics, the god-man relationship, atheism, the nature of man, life and death. Existentialism seeks to reveal what surrounds humanity, making a detailed description of the material and abstract environment in which the (existing) individual develops, so that he or she obtains an understanding of their own and can give meaning or find a justification for their existence. This philosophy, despite the attacks coming more intensely from the Christian religiosity of the XX century, seeks a justification for the existence human.

Existentialism, according to Jean-Paul Sartre, says that in human nature existence precedes essence (which for some is an attack on religious dogmas), thought initiated by Aristotle, specified by Hegel (Phenomenology of Spirit: «If it is true that the embryo is in itself a human being, it is not, however, for itself; for itself the A human being is only human in terms of cultivated reason that has made itself what it is in itself»). In this and only in this resides his (& # 39; reality & # 39;), and continued in Sartre, who indicates that human beings first exist and then acquire essence; that is to say, we only exist and, while we live, we are learning from other humans who have invented abstract things; from God to the existence of a previous human essence, the human being, Sartre understands, is freed as soon as it is freely realized and that is his essence, his essence starts from himself for-himself .

Three schools of existentialism

In terms of the existence and importance of God, there are three schools of existentialist thought: atheistic existentialism (represented by Sartre), Christian existentialism (Kierkegaard, Dostoevsky, Unamuno or Gabriel Marcel) and agnostic (Camus). The latter proposes that the existence or non-existence of God is an irrelevant question for human existence: God may or may not exist. The problem, just by having a firm idea, does not solve the metaphysical problems of man.

Heidegger expressly distances himself from Sartre in his Letter on Humanism. Buytendijk, a psychologist close to Heidegger, admits to being an existentialist. Merleau-Ponty is a great representative of the current, although maintaining more links with Husserl's phenomenology. Martin Buber, for his part, represents a current of Jewish existentialism heavily influenced by Hasidism. While Gabriel Marcel and Jacques Maritain can be classified into a "Christian existentialism" not so much of a Kierkegaardian line but rather a Jasperian/Mounierist one (philosophy of existence and personalism).

Thinkers (list according to alphabetical order)

Dostoyevsky

One of the important antecedents of existentialism is the Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky. In many of his so-called “novels of ideas”, Dostoyevsky presents us with images of people in extreme situations, in a world devoid of values and in which these people have to decide how to act without any guide other than their own conscience. Perhaps one of his most emblematic works in this sense are the Memories of the Underground . There, Dostoyevsky is skeptical about the power of reason to guide us in life, his position is one of rebellion against rationalism.

In novels such as Crime and Punishment, The Possessed, The Karamázov Brothers and The Idiot some themes come together recurring in Dostoevsky's works that include suicide, the destruction of family values, spiritual rebirth through suffering (being one of the capital points), the rejection of the West and the affirmation of Russian Orthodoxy and Tsarism.

Kierkegaard

The most important antecedent of existentialism was the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855). Kierkegaard is considered by many to be the first existentialist philosopher in the history of philosophy. In fact, he invented the term "existentialist" (although he seems not to have used it to refer to himself). There are three features that make us consider him an existentialist philosopher: 1) his moral individualism; 2) his moral subjectivism; 3) the idea of his anguish.

Contrary to the philosophical tradition, which maintains that the highest ethical good is the same for all, Kierkegaard affirmed that the highest good for the individual is to find his own vocation. He said: "I must find a truth that is true for me... the idea that I can live or die for." The idea behind it is that one should choose their own path without the help of universal or objective norms or criteria. This position has been called moral individualism. Contrary to the traditional position that moral judgment involves (or should involve) an objective standard of rightness or wrongness, Kierkegaard argues that no objective or rational basis can be found in moral decisions. The only basis of a meaningful philosophy is the "existing individual" ("situated," we might add); philosophy has nothing to do with an impartial (objective) contemplation of the world or deciphering the “truth”. For him, truth and experience are linked and the idea that philosophy is a kind of exact and pure science must be abandoned.

Later, existentialists would follow Kierkegaard in emphasizing the importance of individual action in deciding matters of morality and truth. Personal experience and acting on your own convictions is essential to get to the truth. The understanding that the agent involved has of a situation is superior to that of a disinterested observer. Existentialists will emphasize the subjective perspective (which allows us to call them, in a sense, subjectivists). This makes them unsystematic philosophers. They oppose the existence of rational, objective and universally valid principles (such as those proposed by Kant). In a sense, existentialists, beginning with Kierkegaard, are "irrationalists": not because they deny the role of rational thought, but because they believe that the most important things in life are not accessible to reason or science.

Martin Heidegger

The German Heidegger rejected that his thought was classified as existentialist. The mistake would come, according to scholars, from the reading and interpretation of the philosopher's first great treatise, Being and Time. In truth, there it is stated that the objective of the work is the search for the «meaning of being» —forgotten by philosophy from its beginnings—, already from the first paragraphs, which properly would not allow us to understand the work —as expressed by the author—as "existentialist"; but Heidegger, after this kind of programmatic announcement, understands that it is prior to the sought ontology or elucidation of being, a "fundamental ontology" and by consecrating himself to it with a phenomenological method, he dedicates himself to a detailed and exclusive descriptive analysis of human existence or Dasein, with a depth and originality unprecedented in history. Western thought, following the phenomenological method of his teacher Edmund Husserl. Subsequently, the rest of his work, which will follow the first mentioned treatise, published in 1927, will deal with other issues in which the theme & # 34; existential & # 34; . This apparent break with the guiding thread of his first thought will be a hiatus in his discourse that the philosopher will never accept as such... But many critics will call it: the second Heidegger and he gives as any philosophical response final (literally) "the silence".

The main characteristic of existentialism is the attention it pays to the concrete, individual and unique existence of man, therefore, in the rejection of mere abstract and universal speculation. The central theme of his reflection is precisely the existence of the human being, in terms of being outside (namely, in the world), of experience, and especially of pathos or in any case the temper of spirit. In Heidegger's expression: «the-being-in-the-world».

Heidegger, in effect, is characterized, according to some, by his firm pessimism: he considers the human being as project (thrown) into the world; Dasein finds itself thrown into an existence that has been imposed on it, abandoned to the anguish that reveals its worldliness, the fact that it can be in the world and that, consequently, it must die. Sartre, following Heidegger, is also far from being characterized by an optimistic style and discourse; he posits, like Heidegger, a human being not just as a project , but as a project : a project in situation. However, these positions do not necessarily have to be understood as pessimistic. For Sartre, the anguish of a conscious soul for finding itself condemned to be free means having, at every moment of life, the absolute responsibility of renewing itself, and Gabriel Marcel starts from this point to support an optimistic perspective, which leads him to overcome any opposition. between man and God, in contradiction with Sartre's atheistic conception.

Marcel

In his first book, Journal Metaphysique, Gabriel Marcel advocated a philosophy of the concrete that recognized that the incarnation of the subject in a body and the historical situation of the individual essentially condition "what is in reality". Marcel is, like Maritain, one of the "French Christian existentialists."

Gabriel Marcel distinguished what he called "primary reflection", which has to do with objects and abstractions. This reflection reaches its highest form in science and technology. For Marcel the "secondary reflection" -used by him as a method- deals with those aspects of human existence, such as the body and the situation of each person, in which one participates in such a complete way that the individual cannot be abstracted from them. Likewise, the secondary reflection contemplates the mysteries and provides a kind of truth (philosophical, moral and religious) that cannot be verified through scientific procedures, but that is confirmed while illuminating the life of each one. Marcel, unlike other existentialists, emphasized participation in a community rather than denouncing human ontological isolation. He expressed these ideas not only in his books, but also in his plays, which presented complex situations where people were trapped and driven towards loneliness and despair, or established a satisfying relationship with other people and with others. God.

As for the family, Marcel, after reflecting on his experience of his mother's early death, affirmed that the family institution was a kind of symbol of a personal reality "much richer and deeper where reciprocal love and mutual donation is the basis or foundation" (It is evident that the theory of mutual gift in the thought of Gabriel Marcel was inspired by the anthropological theory of the same name proposed by Marcel Mauss). In this world, the child sees a haven of happy memories where he returns whenever necessary. In the case of those who died, he simultaneously noted their distance (they are gone) and their closeness (nostalgia).

As mentioned, his texts reflect both his studies of philosophers and currents of thought, —written in the form of a diary— as well as his personal experiences. Thus the second part of the "Metaphysics Journal" it deals with his experience of war and evokes his idea of the transcendence of embodied existence through his own phenomenological analysis.

This methodology was further developed when he opposed the «phenomenology of having» to the «phenomenology of being» that puts him at the gates of metaphysics.

When Marcel was a defender of the rebellious coup leaders (Francoists) against the Republic during the Spanish civil war, it was that the anarchist Albert Camus argued with him in several public letters where he denounced the ethical contradictions of his humanist philosophical reflection. Although attached to existentialism, Gabriel Marcel is considered one of the least existentialist thinkers.

Ortega y Gasset

José Ortega y Gasset, builds his own theory which he will call ratiovitalism, which is opposed to anti-rationalist existentialism. His thinking is considered by many to be different from and even opposed to existentialism, especially to the pessimist. Influenced, like his fellow student Heidegger, by Husserl, who was a teacher of both, he summarized his philosophy in the thesis I am I and my circumstance ; He considered that life is the radical reality, the relationship between the self and the circumstances, the environment in which everything is present, it is experiencing reality, a set of experiences (in German Erlebnisse), in which each one relates to the world; intuition is the experience in which the evidence is present and it is on the evidence that our knowledge rests. "Life is an activity that runs forward, and the present or the past is discovered later, in relation to that future. Life is futurization, it is what is not yet”. Ortega y Gasset is, together with Miguel de Unamuno, the greatest exponent of existentialism in the Spanish language of the XX century. Ortega y Gasset's theories at a certain moment become parallel to existentialism itself, for example when he considers a pantonomy of the Universe.

Jean-Paul Sartre

Sartre's detractors described him as "a nineteenth-century philosopher" to which Sartre replied (late 1970s) "it is true, because what is now is not true philosophy", on the other hand Sartre defined his existentialism concretely as a humanism refuting those who accused him of being a nihilist.

It is practically impossible to summarize Sartrean existentialism in a few lines because it is related to other isms of his time and of all time.

During Sartre's life, he was especially attacked by those who reviled him as an atheist and a materialist who wanted to present Sartre as an "amoral", however of all existentialist thinkers he is perhaps the most moralistic or, rather, the most ethical.

In the first Sartre, as in the first Heidegger, the human being is a being for nothing, and for this reason with an absurd existence that must live in the moment, but very soon he makes a Copernican inversion in relation to the criteria that until then he used philosophy: in things the essence does not even precede existence, the "essence of an object is its very existence" On the other hand, in the human being, existence precedes the essence, it will be the self of each human with its transcendences that will give meaning to human existence, on the other hand, it rejects in Being and nothingness Heidegger's nihilism: nothing is something "unrealizable": it is the destruction of what is already given to create new realities, before this each human being has an existential commitment with the neighbor and, although it seems contradictory and even aporetic, the existential commitment must achieve the freedom of each and every human being, otherwise human existence is meaningless; In one of his apothegms he says with an apparent paradox that & # 34; one is never freer than when one is deprived of liberty & # 34; because -if you are aware (if you are not alienated) of the situation- it is when you are aware of the -always with apparent paradox- necessity (or ἀνάγκη) of freedom, human beings understand Sartre are a being in situation still in a Conditioned Society and art however its destiny is "of gods" (that is, to be free; Sartre's phrase should not be taken literally as a metaphysical postulate), another of Sartre's famous apothegms is: "[human beings] are condemned to freedom"; the ups and downs of Sartriism are interesting as they contain implicit antinomies: the essence of the human being is freedom but (this can be seen in the Merleau-Ponty-Sartre Polemic) "hell is the gaze of the other" because when the other looks at each other who is not him (to put it more simply: when a person observes or considers another) he objectifies him, objects to him and tends to make him an object.

In his last years (and in this we can speak of a second Sartre) after he attempted an existential psychoanalysis that denied the Freudian unconscious for being of "German irrationalist stamp" and instead of the unconscious trying to impose the notion of bad faith before which each human being had to assume his existential commitment, Sartre himself realized it, and recognized it in Sartre for himself and in the Existentialism is a humanism that had erred by flatly rejecting the unconscious (which Nietzsche called Das Es [Lo id] and Freud as Schopenhauer Das Unbewußt), this reconsideration made Sartre say: «As Lacan would say, the human is comic» (note that here Sartre uses the Lacanian symbol for the split subject or cleaved subject not only with Lacanian usage but probably also with irony when suggesting that the human being is dominated by money) in this way, without denying the existential commitment in pursuit of human freedom, is that Sartre admitted as an epilogue to his work that not everything depends on the conscious will of each subject, although he maintained that the human effort in pursuit of freedom is anyway possible.

For decades (from the end of the 1940s to the beginning of the 1980s) for “public opinion” existentialism was presented almost exclusively as Sartriism.

Shestov

Lev Isaákovich Shestov, (Лев Исаа́кович Шесто́в) -in Spanish he is known as León Chestov (Kiev 1866-Paris 1938), He was a Russian existentialist philosopher.

Born Lev Isaakovich Schwarzmann and of a Jewish family, Shestov is considered the greatest exponent of existentialism in Russia. He studied in Moscow and then lived in Saint Petersburg until the Russian Revolution, after which he went into exile in France until his death.

His philosophy has been inspired by Friedrich Nietzsche in regard to anarchism, but was also influenced by the religious significance of Søren Kierkegaard and Blaise Pascal. These influences led him to investigate Western philosophical history in critical approaches to the confrontations between Faith and Reason (Jerusalem-Athens relationship) with the greatest exponents of philosophy and literature, in order to conclude that the first has primacy over the second. regarding the solution of the transcendental problems of man.

This approach consists of a critique of both secular and religious rationalism, of which he argues that reason and knowledge are proud and a consequence of original sin in antiquity that instead of liberating, oppresses; so Chestov's existentialism is spiritual rather than anthropocentric and subjective.

Shestov was at the center of philosophical debate since his arrival in France around 1920 and held conversations with some of the most important European philosophers of the time such as Edmund Husserl, Martin Buber (with whom he discussed after a conversation about Hitler), Karl Jaspers (with whom he maintains a controversy around Nietzsche) or Martin Heidegger, a philosopher he meets in 1928 at Husserl's house and who was invited to the Sorbonne to give a conference through Shestov, as we can read in the correspondence that both kept. Shestov tried to make Heidegger known in France, as he had done with the teacher Husserl before. It was Shestov who wrote about him for the first time for the French public and who invited him to give lectures in France. Shestov met Heidegger through Edmund Husserl who recommended that he read it (Shestov had not yet read it, like Kierkegaard). According to Husserl, Shestov had to read Kierkegaard and Heidegger, because for him one was nothing more than the continuation of the philosophy of the other. All these testimonies have come down to us, above all, as a result of the only disciple that Shestov had, Benjamin Fondane and his book Rencontres avec Léon Chestov. In addition, Shestov's relationship with Husserl and Heidegger is important because he went to As a result of a conversation between the first two, Heidegger came up with the ideas to write his famous text What is metaphysics?, strongly inspired by the ideas he heard in that conversation. What happened in their meetings can be read in more detail in the biography of Lev Shestov that was published in the 1990s in France by his daughter.

Savater points out that for Shestov the human being lives in this world as a prisoner of necessity and the irremediable, subjected to injustice, the crushing of the weakest and finally the fatality of death... and who aspires to a freedom that, still unknown, is found in divinity, in the possibility of a spirituality where everything is possible. For Shestov, his intellectual rival, his & # 39; black beast & # 39; it is Spinoza and his allies Plotinus, Luther, Pascal and Dostoevsky

The way of philosophizing Shestov would have repercussions and influences on some thinkers of the XX century such as Albert Camus or Emil Cioran who recognized that Shestov had left a deep mark on him. As Sanda Stolojan relates in the preface to the anthological edition of Of Tears and Saints by Emil Cioran: In his conversations with Chestov, Benjamin Fondane quotes Chestov's words, according to which the best The way to philosophize consists in 'following one's own way alone', without using another philosopher as a guide, or, better yet, in talking about oneself. Fondane adds: 'the type of the new philosopher is the private thinker, Job sitting on a dunghill'. Cioran belongs to that breed of thinkers.

Lev Shestov influenced some 20th century thinkers who have recognized him as such, such as Sartre, Camus, Heidegger, Levinas, Bataille, Blanchot, Deleuze, Cioran, Ionesco, Jankélévitch among others.

Simone de Beauvoir

She was a French writer, teacher, and philosopher who was a human rights defender and feminist. She wrote novels, essays, biographies, and monographs on political, social, and philosophical topics. Her thought is part of the philosophical current of existentialism and her work The second sex , is considered fundamental in the history of feminism.She was a partner of the philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre.

Next Thinkers

Other prominent thinkers who can be attributed to existentialism, to a greater or lesser degree, would be: Miguel de Unamuno, Edith Stein, Nicola Abbagnano, Nikolai Berdyaev, Albert Camus, Peter Wessel Zapffe, Karl Jaspers, Max Scheler, Simone Weil, Viktor Frankl (Man's Search for Meaning), Paulo Freire and Emmanuel Mounier.

Hans Jonas affirms that the essence of existentialism is a disguised dualism; a deep separation between the world and nature, a separation that generates in man a cosmological and existential tear.

In 1980, Alfredo Rubio de Castarlenas from Barcelona proposed existential realism (22 Historias clínicas de realismo existential, Ed. Edimurtra 1980), which proposes the surprise of seeing oneself exist, when one might not have existed, if Anything prior to us that influenced our origin would have been different. His vision draws from existentialism but is not anchored in anguish, but in the & # 34; joyful despair of having been able not to be & # 34;.

Existentialism and art

Some consider that the concepts developed in existentialist philosophy have been strongly influenced by art. Novels, plays, films, stories and paintings, without necessarily being classified as existentialists, suggest being precursors of his postulates. Here are some authors and representative works:

The novels, short stories and tales of the expressionist writer Franz Kafka, such as The Trial, The Castle, The Metamorphosis; in which the protagonists face absurd, extreme situations, devoid of explanation, although there are answers, to which they never have access, in the manner of those accused by the inquisition to the accusations that originated the process.

Rainer Maria Rilke wrote poetry and novels that directly influenced the existentialists. His Letters to a Young Poet and his novel The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge influenced Sartre's Nausea , and Heidegger wrote a long essay on one of his poems. Many of the existentialist motifs are found in Malte Laurids Brigge's Notebooks: the search for an authentic existence and the confrontation with death, among others.

The work of the Portuguese writer, Fernando Pessoa, in particular: The Sailor and The Book of Restlessness.

Works by French authors such as La Nausea, by Sartre; The Plague, by Camus; Journey to the End of the Night, by Cèline; To End God's Judgment, by Antonin Artaud and the poetry and dramaturgy of Jean Genet. There is also talk of Christian existentialists such as the English novelist Graham Greene or the Spanish novelist José Luis Castillo Puche.

One of the best-known novels by Hermann Hesse: The Steppenwolf, presents a situation in which the protagonist, Harry Haller, finds himself in a profound dilemma about his identity. There are two souls living in his chest: a wolf and a man, representing virtue and humanity, in contrast to the wild satisfaction of instincts and deep misanthropy. At the beginning of the XX century, the work of the Japanese writer Ryūnosuke Akutagawa presents elements of this current.

The films of the Swedish filmmaker Ingmar Bergman, such as The Seventh Seal, Cries and Whispers and Fanny and Alexander, or those of the Russian Andrey Tarkovsky in almost all his work (for example Solaris based on the book by Stanisław Lem uses science fiction as a pretext to give rise to existentialist reflections) or in The Mirror and especially in his latest work: The Sacrifice (or Sacrifice).

Contenido relacionado

Logic

Psychology

Graphology