Eva Peron

Eva María Duarte (Junín or rural area of Los Toldos, May 7, 1919-Buenos Aires, July 26, 1952), also called María Eva Duarte de Perón and better known as Eva Perón or mononymously as Evita, was an Argentine politician and actress, first lady of the Argentine Nation during the presidency of Juan Domingo Perón between 1946 and 1952 and president of the Feminine Peronist Party and the Eva Perón Foundation. She was officially and posthumously declared "Spiritual Head of the Nation" in 1952.

Of humble origins, he migrated to the city of Buenos Aires at the age of fifteen, where he dedicated himself to acting, achieving renown in the theater, radio theater and cinema. In 1943 she was one of the founders of the Argentine Radial Association (ARA), a union of which she was elected president.

In 1944, she met Juan Domingo Perón, then Secretary of Labor and Welfare of the dictatorship later known as the Revolution of 1943, in an act related to helping the victims of the 1944 San Juan earthquake. Already married to Perón actively participated in his electoral campaign in 1946, being the first Argentine politician to do so. In 1947 she promoted and obtained the sanction of the Women's Suffrage Law, after which she sought legal equality for spouses and the homeland. shared authority through article 39 of the Constitution of 1949.

In 1948 he founded the Eva Perón Foundation, through which he built hospitals, asylums, schools, promoted social tourism by creating vacation camps, spread sports among children through championships that spanned the entire country, granted scholarships for students, aid for housing and promoted women in various facets, thus adopting an active position in the struggles for social and labor rights, constituting the direct link between Juan Domingo Perón and the unions. In 1949 she founded the Feminine Peronist Party. In 1951, due to the first presidential elections with universal suffrage, the labor movement proposed Evita as Perón's running mate, as a candidate for vice president. However, she resigned from the candidacy on August 31, on the day known as "Resignation Day", due to pressure from groups opposed to the government, internal struggles within Peronism and cervical cancer that had been diagnosed since 1950, which had worsened.

She died of cervical cancer on July 26, 1952, at the age of 33. After his death, he received official honors, being veiled in the National Congress and in the General Confederation of Labor (CGT), in a massive event never seen before in the country. His body was embalmed and located in the CGT, but the The civic-military dictatorship calling itself the "Revolución Libertadora" kidnapped and desecrated his corpse in 1955, hiding it for sixteen years. At present, her remains are found in the Recoleta cemetery, in the city of Buenos Aires.

He wrote two books: The reason for my life (1951) and My message (1952). She received numerous honors, including the title of Spiritual Head of the Nation, the Grand Order of Isabella the Catholic in Spain from Francisco Franco, the distinction of Woman of the Bicentennial, the Great Cross of Honor from the Argentine Red Cross, the First Category Recognition Distinction from the CGT, the Great Medal for Peronist Loyalty in Extraordinary Degree and the Collar of the Order of the Liberator General Saint Martín, highest Argentine distinction. She has also produced numerous films, musicals, plays, novels and musical compositions about Eva Duarte.

Biography

Birth

According to act no. 728 of the Junín Civil Registry, a girl named Eva María Duarte was born there on May 7, 1922. However, there is unanimity among the researchers to maintain that this act is false and that it was made at the request of Eva Perón herself in 1945, when she was in Junín to marry the then colonel Juan Domingo Perón.

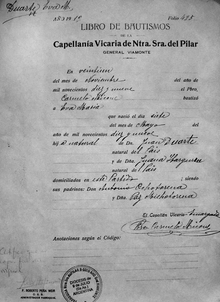

In 1970, the researchers Borroni and Vacca verified that Evita's birth certificate had been falsified and it was then necessary to establish the date and place in which she was actually born. For this, the most important document was the act of baptism, which is registered in page 495 of the Book of Baptisms corresponding to the year 1919 of the Vicarious Chaplaincy of Nuestra Señora del Pilar, carried out on November 21, 1919, where the baptism of a girl named Eva María Duarte, born on May 7, 1919, "natural daughter" by Juan Duarte and Juana Ibarguren.

Today it is practically unanimously accepted that Evita was really born three years before what the state documentation indicates, on May 7, 1919.

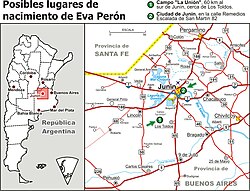

Regarding the place of birth, there are two possibilities that historians have:

- Birth in the city of Junin. Some historians and the most recent research, supported by official documents (part of birth, marriage record and civic notebook), in various testimonies of witnesses and in the sayings of the Evita and his sisters, argue that he was born in the city of Junin because, due to problems with pregnancy, his mother had to move to that city to receive better attention. At the time of the birth of Evita it was customary for women with problem pregnancies in the area of influence of Junin to move there in search of better medical care, which is still so in many cases today. According to this hypothesis, sustained mainly by the Juninian historians Roberto Dimarco and Héctor Daniel Vargas, Eva would have been born in a house located in the current street Remedios Escalada de San Martín n.o 82 (at that time the street was called José C. Paz) being assisted by a university obstetrician named Rosa Stuani. At a short time they would have moved to the domicile located in Calle San Martín n.o 70 (now called Lebensohn), until the mother completely rebuked.

- Birth in the rural area of the General Viamonte party. Other historians argue that he was born in the estancia La Unión, owned by his father, where his family lived at least from 1908 to 1926. The Union was in the party of General Viamonte, exactly in front of Ignacio Coliqueo's awning shop that originated the settlement, in the area known for that reason as "La Tribu", about 20 km from the town of Los Toldos, which was a small city of 3000 inhabitants and 60 km from Junín. Borroni and Vacca collected testimonies in the area of Los Toldos that indicated that Juana Rawson of Guayquil would have been the Mapuche midwife who attended the mother in childbirth, the latter that had already sustained David Viñas in 1965.

Her family

Eva was the daughter of Juan Duarte and Juana Ibarguren.

Juan Duarte (1858-1926), known as the Basque by locals, was a rancher and important conservative politician from Chivilcoy, a town near Los Toldos. Some scholars consider that he was a descendant of Basque-French immigrants with the surname D'Huarte, Uhart, or Douart. In the first decade of the XX century, Juan Duarte was one of the beneficiaries of the fraudulent maneuvers that the government began to implement to to take the land from the Mapuche community of Coliqueo in Los Toldos, appropriating the ranch where Eva was born.

Juana Ibarguren (1894-1971) was the daughter of the cart driver Joaquín Ibarguren and the Creole puester Petrona Núñez. Apparently, she had little relationship with the town, located 20 km away, and therefore little is known about her, but due to the proximity of her house to the Coliqueo toldería, she had close contact with the Mapuche community of Los Toldos. During the births of her children, she was assisted by an indigenous midwife named Juana Rawson from Guayquil.

Juan Duarte, Eva's father, maintained two families, one legitimate in Chivilcoy, with his legal wife Adela D'Huart (-1919) or Estela Grisolía and several children; and another considered "illegitimate", in Los Awnings, with Juana Ibarguren. It was a widespread custom in the countryside, for upper-class men, before the 1940s, which is still common in some rural areas of the country. Together they had five children:

- White (1908-2005).

- Elisa (1910-1967).

- Juan Ramón (1914-1953).

- Erminda Luján (1916-2012).

- Eva Maria (1919-1952).

Eva lived in the countryside until 1926, when her father died and the family was left completely unprotected, having to leave the ranch where they lived. These circumstances of her childhood, in the conditions of discrimination in her early years of the 20th century, marked her deeply.

At that time, Argentine law established a series of infamous qualifications for people if their parents had not contracted a legal marriage, generically called “illegitimate children” or “natural children”. One of those qualifications was that of "adulterous son", a circumstance that the law ordered to be recorded in the birth certificate of the children. That was the case of Evita. Once in government, Peronism in general and Evita in particular promoted anti-discrimination laws to equalize women with men and children with each other, regardless of the nature of the relationships between their parents, projects that were strongly resisted by the opposition, the Church and the Armed Forces. Finally in 1954, two years after her death, the Peronist Party, on the initiative of the deputies Juana Larrauri and Delia Parodi, he managed to sanction a law eliminating discrimination, such as "natural" children, "adulterines", "sacrilegious", "manceres", etc., although maintaining the difference between marital and extramarital children. Juan Domingo Perón himself had been registered as "natural son".

Childhood in Los Toldos

On January 8, 1926, his father died in a car accident in Chivilcoy. The entire family traveled to that city to attend the wake, but the other family forbade their entry in the midst of a great scandal. Thanks to the mediation of a brother-in-law of his father, who was mayor of Chivilcoy at the time, they were able to accompany the procession to the cemetery and attend the burial.

For Evita, the event had a deep emotional significance, experienced as a sum of injustices. At only six years old, she had had little contact with her father. This sequence of events is of great importance in Andrew Lloyd Webber's musical and the film made based on it.

She herself will allude to it in The reason for my life:

To explain my life today, that is to say what I do, according to what my soul feels, I had to go and seek, in my first years, the first feelings... I have found in my heart a fundamental feeling that dominates from there, in total form, my spirit and my life: that feeling is my indignation against injustice. Since I remember every injustice makes me hurt my soul like I get something stuck in it. From every age I keep the memory of some injustice that led me to tear myself intimately.Eva Perón

With the death of her father, Eva's family was financially unprotected. Juana Ibarguren and the children were forced to stop living on Juan Duarte's ranch and move to Los Toldos, living in a small two-room house located on the outskirts of town, at 1021 Francia Street (currently a museum), where he began to work as a seamstress to support her children.

Los Toldos was originally a Mapuche toldería ―hence its name―; that is, an indigenous people. There was the Mapuche community of Coliqueo, installed after the battle of Pavón (1861), by the legendary lonco and colonel of the Argentine Army Ignacio Coliqueo (1786-1871), who came from southern Chile. Between 1905 and 1936 a series of legal tricks were developed there aimed at excluding the Mapuche people from land ownership. Little by little, the indigenous were being displaced as owners by non-indigenous ranchers. Juan Duarte was one of them and for that reason the ranch where Eva was born was precisely in front of the Coliqueo toldería.

During his childhood (1919-1930), Los Toldos was a small rural town in the Pampas, linked to agricultural and livestock activities, specifically wheat, corn and cattle. The social structure was controlled by the rancher, owner of large tracts of land, who established servile relationships with field laborers and tenants. The basic type of worker in that area was the gaucho.

The death of the father jeopardized the financial situation of the family. The following year she Eva she entered primary school, which she attended with difficulties, having to repeat the second grade in 1929, when she was ten years old. Her sisters have told that she was already showing her taste for dramatic declamation and her skills as a juggler. Because of the shape of her face, she would receive the nickname Chola , by which almost everyone called her then, as well as Negrita , which she would keep for the rest of her life. she.

The writer Aurora Venturini, who worked as a psychologist at the Eva Perón Foundation, shared in an interview the following memory about Eva's childhood that her mother told her:

I was told by Dona Juana, her mom, who ran away from school and was going to spend the afternoons with the Indians who were left in Los Toldos, organized quermeses and rifas, danced folklore with them.

Adolescence in Junín

In 1930, his mother decided to move the family to the city of Junín. Eva was eleven years old at the time. There they began to prosper based on the work of Juana Ibarguren, and her children Elisa, Blanca and Juan. Erminda entered the National College and Eva in third grade, at School No. 1 "Catalina Larralt de Estrugamou", from which she graduated with her complete primary education in 1934, when she was fifteen years old.

The first house in which they settled still exists and was located on Roque Vázquez street (later renamed Lebensohn) 86. As the family's economic situation improved due to the work of the older children, especially the After Juan as a salesman for the Guereño toiletries company, the Duartes first moved (in 1932) to a larger house at 200 Lavalle, where Juana organized a homely dining room for lunch, then (in 1933) they moved to Winter 90 and finally (in 1934) to Arias 171..

Eva's artistic vocation flourished in Junín. At school, where he had no major difficulties except for mathematics, he openly stood out for the passion he showed for declamation, acting and participation in whatever show was organized at school, at the National College, at the town's cinema or in radio auditions.

Her music teacher, Délfida Noemí Ruíz de Gentile, remembers:

Eva liked to recite, me to sing. At that time, Don Primo Arini had a music house and, as there was no radio in the village, he placed a speaker at the door in front of his business. Once a week, from 19 to 20 hours, he invited to parade local values to encourage the program Select time. Eva recited poems.

It was there that he participated for the first time in a play, a student performance called Arriba estudiantes. She also acted in another play, Short Circuit, in order to raise funds for a school library. In Junín, Eva used a microphone for the first time and heard her voice coming out of loudspeakers.

At this time he also showed his leadership skills, leading one of the groups in his grade. On July 3, 1933, the day of the death of former President Hipólito Yrigoyen, overthrown three years earlier by a coup, Eva was the only one in her class to go to school with a black bow over her overalls.

At that time, she dreamed of being an actress and migrating to the city of Buenos Aires. Her teacher Palmira Repetti remembers:

A 14-year-old girl, restless, resolute, intelligent, I had for a student there for 1933. He didn't like math. But there was no one better than her when it was about intervening at school parties. She was famous for being an excellent partner. She was a great dreamer. He had artistic intuition. When the school ended, he came to tell me his projects. He told me he wanted to be an actress and he would have to leave Junín. At that time it was not very common for a provincial girl to decide to go to conquer the capital. But I took her very seriously, thinking she'd be fine. My security was, without a doubt, a contagion of his enthusiasm. I understood over the years that Eva's security was natural. He emanated from each of his acts. I remember she leaned on literature and declamation. I ran out of class how many times I could recite in front of the students of other grades. With her cute ways she bought the teachers and got permission to act in front of other boys.

According to historian Lucía Gálvez, in 1934, Eva and a friend suffered a sexual assault by two young men who invited them to travel to Mar del Plata in their car. Gálvez affirms that when they left Junín they tried to rape them, without success, but they left them naked on the outskirts of the city. A truck driver took them back to their homes. The fact—if true—would have had a profound influence on her life.

The writer Norberto Galasso confers credibility to a fact mentioned by Jorge Coscia and Abel Posse, according to those who also in 1934, Eva had the first loving experience of her. Posse details the relationship, stating that it was a young anarchist unionist named Damián Gómez, a railway worker, who shortly after starting the relationship, was arrested and sent to Buenos Aires, where he died victim of police torture, without Eva allowed to visit him in jail. Galasso also relates this version to the underlying motivation that led her to travel to Buenos Aires, as well as an enigmatic reference that she makes in a letter sent to Perón on July 9, 1947 ("I swear it is an infamy; my past It belongs to me, that's why at the time of my death you should know, it's all a lie») and the famous secret mentioned by her confessor, Father Benítez.

Even without finishing elementary school, Eva had to return from Buenos Aires when she couldn't find a job. She then finished primary school, she spent Christmas and New Year's holidays with her family, and on January 2, 1935, when she was only fifteen years old, she permanently migrated to the capital.

In a fragment of La Razón de mi vida, she tells what her feelings were at that moment:

In the place where I spent my childhood the poor were many more than the rich, but I tried to convince myself that there should be other places in my country and the world where things happen otherwise and were rather backwards. For example, the great cities were wonderful places where there was nothing but wealth; and all that I heard told people confirmed that belief of mine. They spoke of the great city as a wonderful paradise where everything was beautiful and extraordinary and even seemed to me to understand, what they said, that even people were there "more people" than those of my people.Eva Perón

The film Evita and some biographies have spread the version that she traveled by train to Buenos Aires with the famous tango singer Agustín Magaldi, after he gave a presentation in Junín. However, this hypothesis has been completely ruled out, after the investigations of Noemí Castiñeiras and Roberto Dimarco -the latter the main historian of Junín-, who verified the non-existence of records on any action by Magaldi in Junín, in 1934. One of her sisters, in addition to her, told that Eva traveled to Buenos Aires accompanied by her mother, who stayed with her until she got a job.

Buenos Aires: career as an actress and unionism

Eva arrived in Buenos Aires on January 3, 1935, at the age of 15. It was part of a great internal migratory process that began after the economic crisis of 1929. This great migration, in Argentine history, had as protagonists the so-called black heads, a derogatory and racist term, used by the middle and upper classes of Buenos Aires to refer to those non-European migrants, different from those that had characterized immigration in Argentina until then. The great internal migration of the 1930s and 1940s and the so-called little black heads constituted the workforce required for industrial development in Argentina, and were the social base of Peronism from 1943.

Shortly after arriving, she obtained a job to act in a secondary role in Eva Franco's theater company, one of the main ones of the time. On March 28, 1935, she made her professional debut in the play La señora de los Pérez, at the Comedia theater. The following day the newspaper Crítica made the first known public comment about her:

Very correct in his brief interventions, Eva Duarte.

For the next few years, he traveled a path of want and humiliation, living in cheap boarding houses, and acting intermittently in plays. Her main company was her brother Juan Duarte, Juancito, five years her senior, the "man" of the family, with whom she always maintained a close relationship and who had also migrated to the capital a few months before. that Eva did it.

In 1936 she was hired by the Compañía Argentina de Comedias Cómicas, led by Pepita Muñoz, José Franco and Eloy Álvarez, for a four-month tour of Rosario, Mendoza and Córdoba. During that tour, Eva appears briefly mentioned in a chronicle of the Rosario newspaper La Capital on May 29, 1936, commenting on the premiere of the play Doña María del Buen Aire by Bayón Herrera, a comedy about the first foundation of Buenos Aires:

The show Oscar Soldatti, Jacinto Aicardi, Alberto Rella, Fina Bustamante and Eva Duarte were rightly completed.

On Sunday, July 26, the same newspaper La Capital published its first known public photo, with the following caption:

Eva Duarte, young actress who has managed to stand out during the season that ends today in the Odeon.

In these first years of sacrifices, she established a close friendship with two other new actresses like her at the time, Anita Jordán and Josefina Bustamante, who she maintained for the rest of her life.

In mid-June 1935 they made their debut with Cada hogar un mundo, by Goycoechea and Cordone, and then they worked on The deadly kiss. From Rosario they traveled to Mendoza. The pace of work was exhausting, on August 2 he went on stage in four performances. They continued the tour in Córdoba and in September they returned to Rosario, to leave again for Córdoba and on the weekend of September 26 they gave four performances in Paraná.

Pierina Dealessi, an actress and major theater manager who hired Eva in 1937, recalled:

I met Eva Duarte in 1937. She showed up timidly: she wanted to dedicate herself to the theatre. I saw a little something so delicate that I told José Gomez, representative of the company where I was a businessman, to give him a location in the cast. It was such an ethereal thing, which I asked, "Young lady, right?" His affirmative response sounded very low, shyly. We were doing the play. A Russian boyI tried it and it seemed good. In his first performances he said small parliaments, but he never did bowls. At the scene, which represented a boîte, Eve had to appear with other girls, well dressed. His figure was beautiful. The girl got along with everybody. I was taking mate with her mates. I prepared it in my chamber. She lived in pensions, was very poor, very humble. He came to the theater early, talked to everyone, laughed, bought biscuits. I saw her so thin, so weak that she said, "You have to take care of yourself, eat a lot, take a lot of mate that makes you very well!" And I put milk on the mat.

Slowly Eva was achieving a certain recognition, participating first in movies as a second line actress, also as a model, appearing on the cover of some entertainment magazines, but above all she began a successful career as a radio announcer and actress. In August 1937 she got her first role. The play, which was broadcast on Belgrano radio, was called White Gold and was set in the daily life of cotton workers in the Gran Chaco.

The prominent actor Marcos Zucker, Eva's co-worker when they were just starting out, remembered those years as follows:

I met Eva Duarte in 1938, at the Liceo Theatre, while working in the play The Grotto of Fortune. The company was Pierina Dealessi and Gregorio Cicarelli, Ernesto Saracino and others acted. She was the same age as me. She was a girl who wanted to stand out, nice, nice and very good friend of all, especially mine, because then, when she had a chance to radioteatro in The Jasmines of the 1980sShe called me to work with her. Since the time I met her at the theatre, and now that she was radio, there was a transformation in Eva. His artistic anxieties were already calmed, he was more applauded, with less tension. On the radio was a young damite, head of company. His auditions had a lot of audience, they were doing great. I was already beginning to have popularity as an actress. Despite everything that is said over there, the Galans had little deal, inside the theater, with the girls. However, I was very close to her and I keep very good memories of that period of our lives. We were both in the same one because we just started and needed to get out, get on our way.

In April 1938, at the age of 19, Eva managed to lead the cast of the recently created Air Theater Company, together with Pascual Pelliciotta, another actor who, like her, had worked for years in supporting roles. The first radio drama that the company put on the air was Los jasmines del eighty, by Héctor P. Blomberg, on radio Miter, from Monday to Friday. Shortly before, in March of that same year, the Argentine Association of Actors had approved her request, receiving her card the following year that accredited her as affiliate no. 639/0.

Simultaneously, he began to act more assiduously in films, such as Seconds Outside! (1937), The Charge of the Brave, The Unhappiest of the Town , with Luis Sandrini, and A Bride in Trouble, in 1941. In that year she made the definitive leap to economic stability when she was hired by the Candilejas Company, sponsored by the Jabón company Radical, which broadcast a series of radio dramas every morning on the El Mundo radio station.

In September 1943, she was hired for five years to perform daily at night, a radio drama called Great Women of All Times, in which the lives of famous women were dramatized. It was broadcast on Belgrano radio and became extremely popular. Francisco Muñoz Azpiri, her librettist, would be the one who years later would write her first political speeches. Radio Belgrano, at that time, was directed by Jaime Yankelevich, who played a fundamental role in the creation of Argentine television a few years later.

Between radio drama and movies, Eva finally achieved a stable and comfortable financial situation. In this way, in 1942 he was able to leave the pensions and buy his own apartment, in front of the Belgrano radio studios, located in the exclusive neighborhood of Recoleta, at Calle Posadas 1567, the same one where three years later he began to live with Juan Perón..

On August 3, 1943, she was one of the founders and first president of the Argentine Radio Association (ARA), the first union of radio workers.

Peronism

In the early days of 1944 Eva met Juan Perón. At that time Argentina was going through a crucial moment of economic, social and political transformations.

The political and social situation in 1944

Economically, the country in previous years had completely changed its productive structure due to a great development of the industry. In 1943, industrial production had surpassed agricultural production for the first time.

Socially, the country was experiencing a large internal migration, from the countryside to the city, driven by industrial development. This led to a broad process of urbanization and a notable change in the population in the big cities, especially Buenos Aires due to the irruption of a new type of non-European worker. They were derogatorily called little black heads by the middle and upper classes, because they usually had darker hair, skin, and eyes than some European immigrants. The great internal migration was also characterized by the presence of a large number of women seeking to enter the new salaried labor market that industrialization was creating.

Politically, the country was experiencing a deep crisis of the traditional political parties that had validated a corrupt and openly fraudulent system based on clientelism. That period is known in Argentine history as the Infamous Decade (1930-1943) and was led by a conservative alliance known as La Concordancia. Faced with the corruption of the conservative government, on June 4, 1943, there was a coup d'état known as the Revolution of '43.

A group of mostly socialist unions and revolutionary unionists, led by the socialist union leader Ángel Borlenghi, took the initiative to establish contacts with young officers who were sympathetic to the workers' demands, finding an echo in colonels Juan Domingo Perón and Domingo Mercante, who decided to make an alliance with the unions to promote the historical program that Argentine unionism had been proposing since 1890. Perón and Borlenghi were promoting great labor conquests (collective agreements, the Statute of the Peón de Campo, retirements, etc.) and winning consequently a popular support that allowed him to begin to occupy important positions in the government. The first position was obtained precisely by Perón, when he was appointed head of the insignificant Department of Labor. Shortly after he obtained that the department was elevated to the important hierarchy of Secretary of State.

Parallel to the progress of the social and labor conquests obtained by the union-military group led by Perón and Borlenghi, and the growing popular support for it, an opposition led by the traditional bosses, military and student groups also began to organize, with open support from the United States embassy, which was gaining support in the middle and upper class. This confrontation would initially be known as "the espadrilles against the books."

Meeting with Juan Domingo Perón

The myth locates the first meeting of Eva (24 years old) with Perón (48 years old and widower since 1938) on January 22, 1944, in an act held at the Luna Park stadium by the Secretary of Labor y Previsión. This act would have been carried out in order to honor the actresses who had raised the most funds in the solidarity collection with the victims of the earthquake that devastated the city of San Juan. Based on Perón's initiatives, generated a great mobilization of solidarity with the people of San Juan, not only from state contributions but also from resources obtained throughout the country by people from various sectors. A week after the earthquake, on January 22, at the Luna Park stadium in the City of Buenos Aires, Perón promoted a massive act in solidarity with the victims of the earthquake and there was a public meeting with Evita, who was summoned by the Secretary of Trabajo y Previsión had participated together with several artists to help the victims. Perón himself later acknowledged to the journalist Tomás Eloy Martínez that Eva had been "the most active" within that group of artists, and that she immediately caught his attention.

That day, prominent figures from Argentine society of the time were at Luna Park, such as the presenter and conductor Roberto Galán, who was the presenter of the event. At one point during the night, Evita approached him and said: "Galancito, please tell me that I want to recite a poem", and that's how she took her to Perón and introduced them.

This is how Perón remembered it:

- Eva came into my life as fate. It was a tragic earthquake that shook the province of San Juan, in the mountain range, and almost entirely destroyed the city, which made me find my wife. At that time I was Minister of Labour and Social Welfare. The tragedy of Saint John was a national calamity (...). To help the population, I mobilized the entire country; I called men and women so that all of them will lay hands on those poor people in that remote province. (...). Among the many that in those days passed through my office, there was a young lady of a fragile but resolute voice, with blonde hair and long falling behind her back, eyes on as well as fever. He called himself Eva Duarte, a theatre and radio actress and wanted to go to the relief work for the unhappy population of San Juan at all costs..

In February, Perón and Eva were already living together and he moved into an apartment next to hers on Posadas street. Meanwhile, Eva continued to develop her artistic career. That year she worked on three daily radio programs: Towards a better future (10:30), where she disseminated the social and labor achievements achieved by the Secretary of Labor; the radio drama Tempestad (18:00) and Queen of Kings (20:30). She also acted in the movie La cavalgata del circo , with Hugo del Carril and Libertad Lamarque.

The '45

The year 1945 was key to Argentine history. The confrontation sharpened between Peronism and anti-Peronism. Throughout the year until the events of October, the anti-Peronist movement would become increasingly stronger, organizing around the United States ambassador Spruille Braden and the business chambers.

Evita, for her part, continued working in radio and film. In April she began filming in Córdoba for La pródiga , a film directed by Mario Soficci, in which she had landed her first leading role. Filming ended in September, and while it was still in the post-production process, the coup d'état broke out that caused Perón's forced resignation, his subsequent arrest and the famous worker mobilization of October 17, which obtained his release and led to the regime. to call elections. In these circumstances and the electoral campaign already launched, Perón asked the San Miguel studios to postpone the premiere until after the elections, although it was not released later either and would only be publicly exhibited on August 16, 1984. That film was his last artistic work, for which he maintained a special affection, to the point of seeing it several times at his home, until the last days of his life. Father Hernán Benítez, her confessor for several years before, recounted that Eva qualified her own artistic performance by saying: «In the cinema, bad; in the theater, mediocre; on the radio, passable. Benítez also thought that Evita was excessively hard on herself, "but not very far from the truth".

On the night of October 8, there was a coup led by General Ávalos, who immediately demanded and obtained Perón's resignation the next day. For a week the anti-Peronist groups had control of the country, but they did not decide to take power. Perón and Eva remained together, going around various houses, including that of Elisa Duarte, Eva's second sister, until October 12 when Perón was arrested in the apartment on Posadas street and confined in the Independencia, which set sail for Martín García Island.

That same day he wrote a letter to his friend Colonel Mercante in which he mentioned Eva Duarte, calling her Evita:

I take care of Evita, because the poor girl has her broken nerves and I care about her health. As soon as I get the retirement, I get married and go to hell.Juan D. Perón

On October 14, he wrote Eva a letter from Martín García in which he told her, among other things:

... Today I wrote to Farrell asking him to speed up my retirement, as soon as we get out we get married and go anywhere to live quietly... What do you say about Farrell and Ávalos? Two scoundrels with the friend. That's life... Tell Mercante to talk to Farrell to see if they leave me alone and we go to Chubut both of us... I will try to go to Buenos Aires by any means, so you can wait quietly and take great care of your health. If the retreat comes out, we'll get married the next day and if it doesn't come out, I'll fix things differently, but we'll settle this situation of helplessness that you have now... What I've done is justified in the face of history and I know that time will give me the reason. I'll start writing a book about this and publish it as soon as possible, then we'll see who's right...

By then it seemed that Perón had been definitively displaced from political activity and that, in the best of cases, he would retire with Eva, to live in Patagonia. However, as of October 15, the unions began to mobilize to demand his freedom, until the great demonstration on October 17, which ended with his release, provoked the recovery of the positions in the government that the military alliance had. union and paved the way for victory in the presidential elections.

The traditional version assigned Eva Perón a decisive role in the mobilization of the workers who occupied Plaza de Mayo but historians currently agree[citation required] that her intervention in those days it was very limited, if it had any. At the time, she still lacked a political identity, union contacts, and firm support in Perón's inner circle. Historical testimonies are abundant in pointing out that the movement that freed Perón was organized directly by the unions throughout the country and the CGT. However, the versions about the true authors of the mobilization are multiple and varied. The meat union leader Cipriano Reyes maintained that he did October 17, in a book titled precisely I did October 17. The historian Lucía Gálvez, for her part, has maintained that the true author of October 17 was an almost unknown woman, Isabel Ernst, secretary and lover of Domingo Mercante, who, taking advantage of her daily dealings with CGT activists and union leaders, mobilized them to trigger the protest.

The journalist Héctor Daniel Vargas has affirmed that Eva Duarte was in Junín, probably at her mother's house, and mentions as proof a power of attorney signed by her that same day, in that city. She apparently could have arrived in Buenos Aires that same afternoon.

As Perón had said in his letters, a few days later, on October 22, he married Eva in Junín. The event occurred at the Ordiales notary, which operated in a house that still exists on the corner of Arias and Quintana, in the center of the city.

The desk used to prepare the civil marriage certificate is currently on display at the Junín Historical Museum. A month and a half later, on December 10, they celebrated the Catholic marriage in the church of San Francisco —an order highly appreciated by Eva—, located at 12th and 68th street in the city of La Plata, with Domingo Mercante and Juana officiating as godparents. Ibarguren, Eva's mother.

Political career

Eva's participation in the electoral campaign

Eva openly began her political career accompanying Perón, as his wife, in the electoral campaign with a view to the presidential elections of February 24, 1946.

Eva's participation in Perón's campaign was a novelty in Argentine political history. At that time, women lacked political rights (except in San Juan) and the wives of the candidates had a very restricted and basically apolitical public presence. Since the beginning of the century, groups of feminists, including people such as Alicia Moreau de Justo, Julieta Lanteri, and Elvira Rawson de Dellepiane, had unsuccessfully demanded the recognition of political rights for women. In general, the dominant macho culture considered it a lack of femininity for a woman to comment on politics.

Eva was the first wife of an Argentine presidential candidate to be present during his electoral campaign and accompany him on his tours. Perón had been proposing since July 1945 that women's right to vote should be recognized, but a few months later the National Assembly of Women chaired by Victoria Ocampo and other conservative sectors opposed a dictatorship granting women the vote on the grounds that that they were in favor of "women's suffrage, but sanctioned by a Congress elected in honest elections" and the project finally failed to prevail.

On February 8, 1946, a few days before the end of the campaign, the Centro Universitario Argentino, the Cruzada de la Mujer Argentina, and the General Student Secretariat organized an act at the Luna Park stadium to express the support of women for the candidacy of Juan Domingo Perón. Because Juan Domingo Perón could not attend because he was exhausted, it was announced that Eva María Duarte de Perón would replace him in speaking. It was the first time that Evita would speak at a political event. However, the opportunity was frustrated because the public angrily demanded the presence of Juan Domingo Perón and prevented him from giving his speech.

During the election campaign, it was already clear at that time that her intention was to play an autonomous political role, even if political activities were prohibited for women. This vision that she herself had of her role in Peronism was clearly expressed in her first speech on her radio, delivered on January 27, 1947 and addressed "to the Argentine woman":

You yourselves, spontaneously, with that warm tenderness that distinguishes the comrades from the same struggle, have given me a name of struggle: Avoid. I prefer to be only "Avoid" to be the wife of the president, if that "Avoid" is pronounced to remedy something, in any home of my homeland.Eva Perón, Message to the Argentinean woman

On February 24, 1946, the elections were held, with the Perón-Quijano formula triumphing with 54% of the votes.

European tour

In 1947 Evita opens the doors of Argentina to Europe: officially invited by the Spanish Government, she begins a tour that takes her through that country, Italy, France, Switzerland, Portugal, Monaco, Brazil and Uruguay. On June 5 a popular farewell rally was held in Plaza Italia-On the 6th, in the afternoon, thousands of people gathered at the El Palomar military aerodrome where their flight would depart. The vice president, ministers, some governors and members of the diplomatic corps also attended.

Perón, Evita and other Peronist leaders thought of an international tour for 1947, unprecedented at that time for a woman, that could place her in the political foreground.

The tour lasted 64 days, leaving on June 6 and returning on August 23, 1947. During it he visited Spain (18 days), Italy and the Vatican (20 days), Portugal (3 days), France (12 days), Switzerland (6 days), Brazil (3 days) and Uruguay (2 days). Her official intention was to act as a goodwill ambassador and learn about the social assistance systems installed in Europe with the obvious intention of encouraging her to return to take charge of a new system of social works. In her procession traveled the Jesuit father Hernán Benítez, by whom she allowed herself to be advised, and who would have influence, upon her return, in the creation of the Eva Perón Foundation.

The press of the time baptized the tour with the name of "Gira del Arco Iris", as a result of an image used by Evita in one of her speeches in Spain, intended to deny the version of a supposed intention of her trip, to establish a warmongering axis between Buenos Aires and Madrid:

Women of Spain, I have not come to form axis but to tend a rainbow of peace with all peoples, as corresponds to the spirit of women.Eva Perón

The flight's first stop was in Natal, Brazil, and then there would be others in Villa Cisneros, in the Spanish Sahara, and in the Canary Islands, from where they would go to Madrid. Evita arrived at the Madrid airport at sunset from Dakhla (then Villa Cisneros) in the current Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic, Spain, it was the first stopover, there Francisco Franco expressed the public recognition of all of Spain, conferring his highest decoration: the Great Cross of Isabel la Católica, which was imposed on him by Franco in a brilliant ceremony. He was in Villa Cisneros, Madrid, Toledo, Granada, Seville, Santiago de Compostela, Pontevedra, Zaragoza and Barcelona. Upon arrival at Barajas and throughout the entire trip to the center of Madrid, a crowd made him the object of enthusiastic cheers, something that It was repeated the following day when he spoke to the Spanish people from the balcony of the royal Palacio de Oriente. In mid-1947, the Spanish were entitled to a daily ration of bread of between one hundred and one hundred and fifty grams. Six months later, with Eva back in her country, that daily quota had doubled thanks to Argentine help. He also managed to get Franco to condone the death sentence handed down to the communist guerrilla Juana Doña Jiménez. Do this and make a colony or an orphanage?", and he advised Franco to transform it into a huge and comfortable asylum for orphaned children because of the civil war. In the following days, she would annoy the Generalissimo by asking for the release of political prisoners, she would criticize in her speeches & # 34; the fratricidal struggles & # 34;. She visited the Naval and Military School of Marín, she went to Pontevedra and Vigo, where she told a large number of people who cheered her: & # 34; In Argentina we work so that there are less rich and less poor. You do the same". She read a message from Perón to the Catalan workers and retired, for a short rest, to the Pedralba Palace. On June 25 she arrived in Barcelona, where she would depart from Spain, where no less than ten thousand people went to the airport.In Paris she Evita attended the signing of the Franco-Argentine Trade Agreement, for the provision of food for the country Gallic.

In France, magazines like Paris Match" or "Time" they dedicated several numbers to their tour.

On several occasions, Eva expressed her displeasure about the way workers and humble people were treated in Spain, as well as the lack of democracy and the existence of political prisoners. She maintained a strained relationship with Franco's wife, Carmen Polo, due to her insistence on showing him the historic Madrid of the Habsburgs and the Bourbons instead of the public hospitals and working class neighborhoods or "shanty towns". During her stay in Spain, she received a letter from the little son of the communist militant Juana Doña, asking her to intercede with Franco for her mother who was sentenced to death in those days. At the child's request, Evita managed and obtained the commutation of the sentence.

Back in Argentina, he would say:

Franco’s wife did not like the workers, and every time she could label them as “reds” because they had participated in the civil war. I stood up a couple of times until I could no longer, and I told her that her husband was not a ruler by the people's votes but by imposing a victory.

Despite these comments that seem to position the first lady of Argentina as a person with great sympathy for the communists, Eva came to make strong criticisms of the left, mainly in 1948, when she said that the socialists "they did nothing for the workers and there were only 4 fossils".

As for Portugal, he did not have a “too favorable” impression and thought that António de Oliveira Salazar exercised an implacable dictatorship while the people found themselves in misery. There he visited the Encarnación neighborhood and the FNAT headquarters and had lunch in Guincho with King Humberto II of Italy, exiled in Portugal.

The trip continued through Italy, where he had lunch with the Minister of Foreign Affairs, visited childcare centers. There he writes in the local newspapers, alternating dinners with the highest representatives of the government or civil society and meetings with workers.

In Vatican City, she was received by Pope Pius XII, who presented her with the gold rosary and the pontifical medal that she carried in her hands at the time of her death, after holding a 15-minute meeting alone. No direct testimony has remained of what the Pope and Eva discussed there, with the exception of a brief later comment by Perón on what his wife had told him. The Buenos Aires newspaper La Razón covered the news as follows:

The Pope then invited her to sit next to her desk and began the audience. Not a single word has been officially made known of the conversation held by the Supreme Pontiff and the lady of Perón, but a member of the papal house indicated that Pius XII gave the lady of Perón her personal thanks for the help that Argentina has provided to the European nations scourged by the war, and for the collaboration that Argentina has provided in the relief work of the Pontifical Commission. After 27 minutes, the Supreme Pontiff pressed a small white button on his desk. A bell ringed in the antechamber and the audience came to an end. Pius XII gave the lady of Perón a rosary with a gold medal commemorating her pontificate.

In Italy, she received news of the explosion of the Panigaglia ship in the port of Civitavecchia, near Rome. Evita soon took an interest in the victims of the accident, and ordered the Argentine ambassador in Italy to send a telegram with her condolences to the families and to make a donation to the families of the victims. During her tour of Rome, she would take advantage of her free time to visit museums and art galleries.

After visiting Portugal, she headed for France, where she was affected by the publication in France Dimanche magazine of a photo of her as a model, posing for a soap ad, appearing alongside to another photo, this time of Perón posing with a Mapuche woman. She anyway she presided over the signing of a commercial treaty for the purchase of wheat, she received the Legion of Honor, and she met with the president of the National Assembly, the socialist Édouard Herriot, among other politicians. The Jesuit Benítez took her to Notre Dame to speak with the apostolic nuncio in Paris, Monsignor Ángelo Giuseppe Roncalli, future Pope John XXIII, who gave her the following recommendation:

If you are really going to do so, I recommend two things: that you completely dispense with all bureaucratic trash, and that you consecrate yourself without limits to your task.

The priest Benítez affirmed that Roncalli was impressed by the figure of Evita bowing her head in front of the altar of the Virgin while the Argentine National Anthem was being played, and that she said: "The Empress Eugenia de Montijo has returned!"

The tour continued through Switzerland, where he met with political leaders. He ultimately ruled out visiting Britain because the royal family was in Scotland, and before returning he visited Brazil and Uruguay. The finishing touch of the tour was, on his return, his presence at the Inter-American Conference for the Maintenance of Continental Peace and Security, which was held in Rio de Janeiro on August 20, 1947, which concluded with the signing of the Treaty Inter-American Reciprocal Assistance (TIAR).

Women's Rights

In Argentine history there is unanimous recognition of the fact that Evita carried out a decisive task for the recognition of equal political and civil rights between men and women. During her European tour she clearly stated her point of view on this issue:

This century will not go to history with the name of "the century of atomic disintegration" but with another much more significant name: "the century of victorious feminism".Eva Perón

Eva Perón was a close friend of María Cristina Vilanova de Árbenz, first lady of Guatemala, who was also a very influential woman in the revolutionary government of Jacobo Árbenz.

Women's Suffrage

During the campaign for the 1946 elections, the Peronist coalition included in its platforms the recognition of women's suffrage. Perón from his position as Vice President, tried to sanction the law of women's suffrage. However, the resistance in the Armed Forces in the government, as well as from the opposition, which alleged electoral intentions, frustrated the attempt. After the 1946 elections, Evita began to openly campaign for the female vote, through rallies of women and radio speeches, at the same time that his influence within Peronism grew. Later, she Evita created a party of women leaders, with grassroots units, something that did not exist anywhere else in the world. She said that women not only have to vote, but they have to vote for women: that is why at that time there were women in Deputies and Senators, who increased in subsequent elections. Argentina was very advanced.On February 27, 1946, three days after the elections, twenty-six-year-old Evita gave her first political speech in an act organized to thank women for their support of Perón's candidacy.. On that occasion, she Evita demanded equal rights for men and women and in particular women's suffrage:

The Argentine woman has exceeded the period of civil guardianship. Women must assert their action, women must vote. The woman, moral resort of her home, must occupy the place in the social gear complex of the people. It calls for a new need to organize in more widespread and remorseful groups. In sum, it demands the transformation of the concept of women, which has been sacrificially increasing the number of their duties without asking for the minimum of their rights.Eva Perón

The bill was presented immediately after the new constitutional government took office, on May 1, 1946. The opposition of conservative prejudices was evident. Evita constantly pressured parliamentarians to approve it, even causing protests from the latter for her meddling.

Despite the fact that it was a very brief text in three articles, which practically could not give rise to discussions, the Senate only gave half approval to the project on August 21, 1946, and it was necessary to wait more than a year for the Chamber of Deputies sanctioned on September 9, 1947 —unanimously— Law 13,010, establishing equal political rights between men and women and universal suffrage in Argentina.

To celebrate the law that recognized the political rights of women, the CGT called an event in the Plaza de Mayo on September 23, in which Eva, the former union leader and Interior Minister Ángel Borlenghi and Perón spoke, in that order. During the ceremony, the president signed the decree promulgating the law on the balcony and handed it over to Eva, who immediately afterwards gave her speech addressed to the "women of my country", which began with the following paragraphs:

Women of my homeland, I receive at this moment from the hands of the Government of the Nation, the law that enshrines our civic rights, and I receive it before you with the certainty that I do it in the name and representation of all the Argentine women, feeling joyfully that they shake my hands to the contact of the laurel that proclaims victory. Here are my sisters summed up in the clenched letter of few articles a long history of struggles, stumblings and hopes, therefore there are in it crisps of indignation, shadows of occasional threats, but also joyful awakening of triumphal auroras, and this last thing that translates the victory of the woman over the incomprehensions, the denials and the vested interests of the castes repudiated by our national awakening, the sanitation, has only been possibleEva Perón

The Women's Peronist Party

In 1949 Eva Perón sought to increase the political influence of women by founding the Feminine Peronist Party (PPF), on July 26 at the Cervantes National Theater in the City of Buenos Aires. The PPF was led exclusively by women, was fully autonomous within the movement, and it was organized from basic female units that were opened in the neighborhoods, towns and unions channeling the direct militancy of women.

On November 11, 1951, general elections were held. Evita she voted in the hospital where she was hospitalized, due to the advanced state of the cancer that would end her life the following year. For the first time, Argentine women were able to vote and be voted for. 64% of women voted for Peronism, a percentage slightly higher than that of men, who voted 63% for Perón's re-election. Likewise, the Feminine Peronist Party managed to elect 23 deputies, three delegates from national territories and 6 senators ―the only women present in the National Congress―, and 80 provincial legislators.

Legal equality in marriage and parental authority

The political equality of men and women was complemented by Eva's drive for the constitutional reform of 1949 that established the legal equality of spouses and shared parental authority guaranteed by article 37 (II.1), as well as the rights of the child and the elderly, the latter proposed by Eva Perón herself.

The military coup of 1955 abolished the Constitution, and with it the guarantee of legal equality between men and women in marriage and against parental authority, reappearing the priority of men over women. The 1957 constitutional reform did not reincorporate this constitutional guarantee either, and Argentine women remained legally discriminated against until the shared parental authority law was enacted in 1985, during the Alfonsín government.

Evita also proposed recognizing the economic value of the work of maintaining homes and raising children, carried out mainly by women, through some remuneration method that should be studied.

Relationship with workers and unions

Eva Perón established a strong relationship, close and at the same time complex, with the workers and the unions in particular, which characterized her.

In 1947, Perón ordered the dissolution of the three parties that supported him, the Labor Party, the Independent Party and the Unión Cívica Radical Junta Renovadora, to create the Peronist Party. From that moment on, the unions were recognized as the "backbone" of the Peronist movement, which in practice meant that the Peronist Party took the form of a quasi-labor party. With the creation of the Feminine Peronist Party, the Peronist movement was organized into three autonomous branches: the political branch, the union branch, and the women's branch.

In this scheme of heterogeneous and often conflicting powers that came together in Peronism, understood as a movement encompassing multiple classes and sectors, Eva Perón occupied a role of direct and privileged link between Perón and the unions, which allowed the latter to consolidate a position of power, albeit shared.

For this reason, it was the union movement that promoted Eva Perón's candidacy for vice president in 1951, a candidacy that was highly resisted, even within the Peronist Party, by sectors that wanted to prevent the union sector from advancing.

Evita had a highly combative vision of the struggle for social rights and thought that "the oligarchy", "dehumanized capitalism" and "imperialism" would even act violently to annul them. Evita's speech openly tended to vindicate the rights values and interests of workers and women.

The close relationship between Evita and trade unionism was evidenced in the donation that the Eva Perón Foundation made to the CGT of the building where it installed its headquarters ―adjacent to the new headquarters of the foundation― and by the decision to establish it after her death, that his embalmed corpse would remain in the workers union until the monument dedicated to his memory was built.

Union action

Eva carried out intense union work from the Secretariat of Labor and Welfare (STYP) ―transformed into a Ministry in 1949― managing all kinds of initiatives and claims, organizing new unions, participating in collective negotiations, attending assemblies in the factories, or simply receiving donations from the unions for their "crusade", which became more and more numerous. Every Wednesday, Evita accompanied the CGT delegation that met with the president. Marysa Navarro says that Evita's union work was decisive for the "Peronization of the unions".

For the first half of 1948, Evita was already recognized by the union leaders as a decisive manager of the labor conquests and of the power achieved by the labor movement within the government, a circumstance that explains her appearance that year, along with Perón, in the two main workers' mobilizations, the one on May 1 and the one on October 17.

International action

The Peronist government was the first in Latin America to establish a bilateral trade agreement with Israel. Parallel to the state action, the Eva Perón Foundation sent clothes and medicines – which arrived by boat at the port of Haifa – to alleviate the suffering of the thousands of Jewish migrants arriving in Israel. When in April 1951 the Israeli minister Golda Meir visited Argentina, she personally thanked Evita for the donations. She was accompanied to the interview by the then Plenipotentiary Minister of the Israeli Embassy in Buenos Aires, Jacobo Tsur. On this occasion, Evita told Mrs. Meir: "The rebirth of Israel is an extraordinary event for humanity, and all of us Peronists look at ourselves in that marvelous mirror, because we repudiate what they did to the Jews in Europe and we also admire the way they knew how to overcome the tragedy in a short time”.

Golda Meir responded to Evita: “We have been persecuted and driven from everywhere. We value how in Argentina, today, we are treated as equals, without any type of discrimination”. On Sunday, April 8, 1951, a crowd of Jews filled Luna Park to listen to Meir and, on that stage, she once again praised the Justicialist government.

Perón and Evita's position against Judeophobia was clear, participating in the inauguration of the brand new headquarters of the Argentine Israelite Organization (OIA), in August 1949. During the harsh winter of 1950 he would send coats, shoes and food for the poor children of Washington. In 2002, the Argentine ambassador in Washington, Diego Guelar, asked that the city of Washington recognize Evita's concern for the poor children of the District and that she name a public space after her. The donation on behalf of Eva Perón and her Social Aid Foundation had been carefully arranged with the Rev. Ralph Faywatters, who headed the Children's Aid Society, a charitable organization that protected black children in Washington. Also on the same days, France received a similar donation, which was shared among the poor children of Montmartre.

The Eva Perón Foundation and social assistance

The activity for which Evita stood out during the Peronist government was social aid aimed at addressing poverty and other social situations of helplessness. Traditionally in Buenos Aires this activity was in the hands of the Sociedad de Beneficencia de la Capital Federal, an old quasi-state association created by Bernardino Rivadavia at the beginning of the century XIX directed by a select group of women from the upper class. As early as the 1930s it began to become apparent that the Welfare Society and similar institutions in other parts of the country, as well as welfare, had become obsolete and unsuitable for urban industrial society. Starting in 1943, charitable organizations began to be reorganized and on September 6, 1946, the capital entity was intervened. Peronism completely reorganized the action of the State in matters of social assistance. Part of this task was developed through the successful public health plan carried out by the Minister of Health Ramón Carrillo; part was developed from the new social welfare institutions such as the generalization of retirement and pensions; and part was developed by the National Directorate of Social Assistance created in September 1948, that in time would come to be organized as a ministry, under various names, such as "Social Welfare" or "Social Development." In this context, the Eva Perón Foundation (FEP) appeared, with the aim of institutionally organizing the social action that Eva had been carrying out in the Ministry of Labor and Welfare (STYP), a task that the press called her "Social Aid Crusade", and union donations that had begun to multiply.

On July 8, 1948, the Eva Perón Foundation was created, chaired by Evita, which developed a gigantic social task that reached practically all children, the elderly, single mothers, and women who were the only breadwinner for the family, belonging to the most deprived strata of the population. Eva explained in La raison de mi vida what her focus was on social action, giving priority to the personalization and inclusive dignity of vulnerable sectors:

Many works have been built with rich criteria and the rich, when he thinks for the poor, thinks of the poor. Others have been made on the basis of state; and the State only builds bureaucratically, i.e., with coldness in which the great absentee is love.Eva Perón

The Foundation carried out a wide spectrum of social activities, from the construction of hospitals, schools, transit and nursing homes, vacation camps, popular grocery stores, to granting scholarships for students, aid to build low-income housing, a agrarian plan to support small rural producers, massive deliveries of sewing machines and promotion of women in various facets. He built the modern workers' housing in Ciudad Evita, twelve advanced polyclinics throughout the country, where care was completely free, and he directed the School of Nursing. The Foundation annually held the famous Evita National Games, in which hundreds of thousands of children and young people from humble sectors participated, which, while promoting sport, also allowed for massive medical check-ups. The Foundation also delivered en masse, each year's end, cider and sweet bread to the most deprived families, the latter being highly criticized by anti-Peronist opponents. The Foundation employed 14,000 people, including 850 nurses who were one of its main emblems. Evita also personally attended to each letter and each complaint.13,402 women obtained employment thanks to the Foundation, between 1948 and 1950, and 8,726 boys were admitted for their care in schools or institutions of the Foundation between 1948 and 1950. The Foundation also provided assistance to other countries, among others, to Croatia, Egypt, Spain, France, Israel, Uruguay, Paraguay, Bolivia, Honduras, Japan and Chile.

Eva's main collaborators in the FEP were the prestigious surgeon Ricardo Finochietto, Father Hernán Benítez who installed his parish in the working-class neighborhood of Saavedra built by the Foundation, Atilio Renzi, Alfredo Alonso and Ramón Cereijo.

The Foundation's funds came from various sources: taxes from lotteries, casinos and races (Laws 13941 and 14044), personal donations, quotas established in collective agreements, contribution of 2% of the Christmas bonus (Law 13992), quotas established in collective agreements, etc. A total of 2,350 elderly people were able to be admitted to the homes for the elderly that the Foundation built. On October 17, 1949, the first of them was inaugurated in Burzaco and, until 1950, another four were opened. There they were fed and cared for by nurses and nuns. A total of 60,180 people were cared for a year after the first Transit Home was set up. Three were built, with a total of 1,150 beds. The objective was to remedy the housing shortage, giving a momentary protection.

The State not only contributed funds, but also real estate, personnel and means of transportation. The opposition reproached him that despite the fact that the contributions, some of them compulsory, came from everyone, the work was carried out in the name of Eva Peron.

The Foundation also made solidarity aid for various countries such as the United States, Israel, Peru, Ecuador and Colombia. In 1951, Golda Meir, then Israeli Minister of Labor and one of the few women in the world who had achieved a prominent political position in a democracy, traveled to Argentina to meet with Eva Perón and thank her for the donations to Israel in the first moments. of its creation.

The Eva Perón Foundation operated in various buildings and warehouses, while Evita set up her office in an office located on the first floor of the Ministry of Communications, now the Kirchner Cultural Center where the room is kept as a museum. At the end of 1950, the National Congress donated land to the FEP on Paseo Colón at 800, next to the new CGT building, where the headquarters began to be built, a large neoclassical building with large allegorical statues of Leone Tommasi in her top. The destruction of documentation by the Revolución Libertadora has made it impossible to know exactly when Eva Perón began working in the new building, but there is a coincidence that it was for a very short time. In 1955 the building would be assaulted by the coup groups, destroying the documentation and the statues of Tommasi; shortly after it was handed over to the University of Buenos Aires, which installed the Faculty of Engineering there. In 2011 the building was declared a national historic monument by Law 26714.

The writer Aurora Venturini, who worked at the Eva Perón Foundation as a psychologist, has left her memory of Evita in this area:

The Foundation arrived at eight o'clock in the morning and went to four o'clock the next day. His legs were swollen, his shoes were pulled under the desk and he was barefoot... he had to see it closely, in his daily treatment, he could be so unbearable. When he told me or others, "I want this for tomorrow," he had to be ready because if he was not escaped from gross insults, he was releasing all his anger in which he was ahead, he jumped. It was hard to be with her in those moments. Then I understood her: she was running out of time, she was in a hurry... I remember the fly boy. I had accompanied her to a tour of the poor neighborhoods. By then, the villas were good, they could enter, there was no violence, only poverty, much poverty. We were approached by a boy who had a completely black head... they were flies. Evita didn't stop and cry, then he asked us to take him to the hospital where he was healed, but she was never impressed. Those things gave him immense anger, he went crazy.

After the military coup, the Foundation was sacked in September 1955. Once the Lonardi dictatorship was installed Marta Ezcurra of the Argentine Catholic Action ordered the immediate intervention of each of the institutes and summoned the members of the “ civil commandos” orders the immediate eviction of all the boys and girls, orders the destruction of all the bottles in the Blood Banks of the Foundation Hospitals because they contain “Peronist” blood, orders the military assault against the School of Nurses, and orders its closure definitive. It determines the confiscation of all furniture from hospitals, children's homes, schools homes and transit homes for being too luxurious and takes them to the houses of the members of the civil commandos, much of the furniture would end up in the houses of the members of the civil commands. Each Home was intervened by Civil Commandos who, in the case of the Termas de Reyes Children's Recovery Clinic, in Jujuy, went to the extreme of expelling the children to leave a hospital inaugurated there shortly after. luxury casino.

Democracy Journal

At the end of 1947, Evita managed the purchase of the newspaper Democracia, the only newspaper that had supported Perón's candidacy in the 1946 elections. The newspaper became "Evita's spokesperson", with a circulation of more than 300,000 daily issues. Since mid-1948, he published weekly on the cover, articles written by Eva Perón, on current political issues, although these participations became more spaced from 1949.

The titles of the articles published by Eva Perón in Democracia openly reflect her social and political concerns. Some of them were: "Why I am a Peronist", "Social aid, yes; alms no», «Social significance of the “shirtless”», «To forget children is to renounce the future», «The current duty of the Argentine woman», «Towards the total emancipation of the shirtless from the countryside», «My conversations with General Perón", "National meaning of October 17", "The Argentine woman supports the reform", "The people want Argentine solutions for Argentine problems".

Rights of the elderly

On August 28, 1948, Eva published her Decalogue of the Rights of the Elderly, a pioneering global initiative in the fight for the recognition of the elderly. that moment is celebrated in the country on Old Age Day on August 28. On that occasion, Evita read, at the Ministry of Labor, the declaration of the Rights of the Elderly, which she placed in the hands of President Juan Perón, requesting that it be incorporated into the legislation and institutional practice of the Nation. The decalogue established the following rights: assistance, housing, food, clothing, physical health, moral health, recreation, work, expansion, and respect.

That same year, Argentina took the decalogue to the United Nations, proposing to the General Assembly to approve a norm recognizing the human rights of the elderly. At that time, the United Nations had not yet approved the first human rights instrument, which would only be approved as a mere non-binding "declaration" in December of that year, after overcoming several inconveniences. In support of the universal recognition of the rights of the elderly, Evita published two articles in French newspapers: «The world cannot be insensitive to the fate of the elderly» in Ce Matin and «Christian emotion and justice Social” in the magazine Le Tribune des Nations.

The rights of the elderly elaborated by Evita and proposed by Argentina, were finally not included in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights nor approved as a complementary declaration. It would take 43 years for the early Argentine proposal to finally lead to the approval by the United Nations of the United Nations Principles in Favor of Older Persons, through Resolution 46/91 of the General Assembly of December 16, 1991.

In 1949 the Constituent Convention incorporated the Decalogue of the Elderly prepared by Evita and incorporated it into the new text of the Constitution as article 37, III.

Vice Presidential Candidacy

The 1951 general election was the first time that women were able to run, not just to vote but as candidates. Due to her great popularity, the General Confederation of Labor proposed Evita's candidacy for the position of Vice President of the Nation, accompanying Perón, a fact that not only implied taking a woman to the National Executive Branch, but also strengthening the union sector in the government peronist. The bold move unleashed a sharp internal struggle within Peronism and intense efforts by the power groups, in which the conservative sectors pressed hard to avoid it. Simultaneously with this process, Evita developed cervical cancer that would end her life in less than a year.

In this context, on August 22, 1951, the Cabildo Abierto del Justicialismo took place, convened by the General Confederation of Labor. The meeting was attended by millions of workers at the corner of Moreno and 9 de Julio, and was an unusual historical event. In its course, the unions asked Evita to accept the candidacy for vice president. Both Perón and Evita took the floor successively to suggest that the charges were not important and that Evita already occupied a higher place in the consideration of the population. As the words of Perón and Evita revealed the strong resistance that her candidacy aroused, the crowd began to demand that Evita accept her right there. At some point, a voice in the crowd even demanded from Perón:

At that moment there was a dialogue between the crowd and Evita, completely unusual in large events:

Text of the dialogue between Evita and the crowd at the Open Cabildo of August 22, 1951-Evita (speaking the crowd and Perón): Today, my general, in this Open Court of Justice, the people asked that I wanted to know what this is about. Here you know what this is about and you want General Perón to continue to lead the fates of the Homeland.

Avoid: This takes me by surprise. Never in my heart of humble Argentine woman I thought I could accept this position... Give me time to announce my decision to the country in chain.

People: With Evita!

Avoid: I will always do whatever the people want. But I tell you that just as five years ago I said I preferred to be Evita, before the president's wife, if that Evita was said to relieve some pain from my homeland, now I say I still prefer to be Evita. The Homeland is saved because it is governed by General Perón.

People: Answer him, answer him!

Mirror (CGT): Ma'am, the people ask you to accept your position.

Avoid: I ask the General Confederation of Labour and you, for the affection that we profess each other, for such a transcendental decision in the life of this humble woman, to give me at least four days.

People: No, no, let's stop! Let's go to the general strike!

-Avoid: Companions, compañeros... I don't give up my fighting post. I give up the honors. (chuckles). I will finally do what the people decide. (Applause and live). Do you think that if the vice president's post was a position and if I had been a solution, I wouldn't have answered since I did?

People: Accounting!

Avoid: Companions, for the affection that binds us, please do not make me do what I do not want to do. I ask you as a friend, as a companion. I'm asking you to deconcentrate. (The crowd does not retire). Companions, when did Evita disappoint you? When has Evita not done what you want? I ask you something, wait till tomorrow.

Mirror (CGT): The roommate Evita asks us two hours to wait. We're staying here. We don't move until you give us the favorable answer.

The crowd understood those words as a commitment from Eva Perón to accept the candidacy and withdrew. In fact, the “evitista” newspaper Democracia headlined the next day “They accepted!”. However, nine days later, Eva herself spoke on the radio to report that she had decided to resign from the candidacy. That date was designated by supporters of Peronism as Renunciation Day.

The reasons and pressures that led to Evita's resignation are the subject of various analyses. Among them, the deterioration of her health, which was notable at the time and which would cause her death less than a year later, turned out to be an important factor. However, this did not prevent the CGT proposal from highlighting the internal struggles in Peronism and in society, in the event that a woman supported by the unions could be elected vice president and eventually even president of the Nation. The biographer Marysa Navarro highlights the role played by gender prejudices in the resignation, which even led one of the main Argentine writers, Ezequiel Martínez Estrada, to question Perón and Evita saying: "Actually, he was the woman and she the man".

Less than a month after Evita's resignation, there was a failed civil-military coup d'état, which involved senior political and military leaders, which was defeated by the energetic reaction of the government and the rapid mobilization of the CGT, declaring the general strike. The day after the coup, Evita brought together the top union leaders and the head of the Army, to organize worker militias capable of defending democracy, in the event of a new coup.