Euro

The euro (EUR or €) is the currency used by the institutions of the European Union (EU), as well as the currency official eurozone, made up of 20 of the 27 EU member states: Germany, Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Croatia, Estonia, Finland, France, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands and Portugal. In addition, 4 European micro-States have agreements with the European Union for the use of the euro as currency: Andorra, Vatican City, Monaco and San Marino. On the other hand, the euro was adopted unilaterally by Montenegro and Kosovo.

Some 340 million citizens live in the 20 eurozone countries. In addition, more than 240 million people around the world use currencies pegged to the euro, including more than 190 million Africans.[ citation needed] The euro is the second most traded reserve currency in the world, after the US dollar.

The name "euro" was officially adopted on December 16, 1995 in Madrid. The euro was introduced to world financial markets as a currency of account on January 1, 1999, replacing the former European Currency Unit (ECU) in a ratio of 1:1.

The coins and banknotes entered into circulation on January 1, 2002 in the 12 States of the European Union that adopted the euro that year: Germany, Austria, Belgium, Spain, Finland, France, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Portugal. In addition, the European microstates of Vatican City, Monaco and San Marino, which had agreements with countries of the European Union, and Andorra unofficially also adopted the euro that year. In 2011, Andorra signed a monetary agreement with the European Union, which entered into force on April 1, 2012, which meant the official adoption of the euro by Andorra.

On January 1, 2007, Slovenia joined the Eurozone. Malta and Cyprus joined on January 1, 2008, and Slovakia on January 1, 2009. Estonia joined on January 1, 2008. 2011, being the first country that had been part of the USSR to become a member of the eurozone. Latvia joined on January 1, 2014 and Lithuania joined on January 1, 2015. Finally, Croatia adopted the euro on January 1, 2023, being the last country to adopt the common European currency.

Seven countries of the European Union have not adopted the euro yet: Bulgaria, Denmark, Hungary, Poland, the Czech Republic, Romania and Sweden. Neither did the United Kingdom during its years of membership in the Union.

Features

The euro is divided into one hundred cents. Although "cent" —plural "cents", in both cases without a full stop or tilde— is the official name for the division of the euro in all languages, in the language usual, however, it is translated by the equivalent in each language (in Spanish centimo, in Greek λεπτό, in Italian centésimo, in French < i>centime, etc.) and is pluralized according to the habitual use of the language.

Euro banknotes —of 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200 and 500 euros— are identical for all countries. The euro coins —of 1, 2, 5, 10, 20 and 50 cents and 1 and 2 euros— have the same obverse in all countries, but different reverses depending on the country of minting. However, all euro coins from any country can be used in all eurozone countries.

The design on the common side of the coins is the work of Luc Luycx of the Royal Belgian Mint. The coins, regardless of their national reverse, are valid in any country in the euro zone.

As of 2004, a European Union directive allows the minting of a commemorative two-euro coin every year —two coins a year since 2013— in each country in the euro zone. These issues, the production of which is determined by the normal minting of coins in each country, retain the common obverse of the Eurozone and the reverse shows the commemorative motif. These joint commemorative coins are in addition to those that can be issued by each state.

The main motifs of the first series of euro banknotes are: doors and windows, which symbolize the open spirit of the European Union; the elimination of borders and integration is represented by bridges on the reverse of the banknote. In addition, the general theme of the series is "Ages and Styles", featuring a specific architectural style on each banknote.

The design of the banknotes is by Robert Kalina of the Oesterreichische Nationalbank (OeNB - Austrian National Bank).

The euro is the successor to the ECU or European Currency Unit (in English: European Currency Unit). At the Madrid meeting on December 16, 1995, German Chancellor Helmut Kohl pointed out that it sounded the same to him as Ein Kuh, which in German could be understood as "a cow". For this reason it was determined that the single community currency was called Euro, having a 1:1 parity with the ECU.

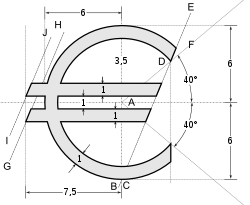

The euro symbol (€), developed by the European Commission, is inspired by the letter epsilon (ε) of the Greek alphabet. This symbol was chosen as a reference to the initial of Europe, E. The two parallel lines refer to stability within the euro area.

Like all other currencies, euro is a common name and must be written in lower case. Its plural is euros. The international code for the euro is EUR and it has been registered with the International Organization for Standardization (ISO); It is used for business, commercial and financial purposes.

There is no official symbol for the cent, although the usual translation and abbreviations for each language are often used. In Spanish, we use cént. (plural: cts.) as a reminiscence of the peseta cent. In Ireland, the ¢ symbol is sometimes used in shops.

| 5 euros | 10 euros | 20 euros | 50 euros | 100 euros | 200 euros | 500 euros |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classic | Romanesque | Gothic | Renaissance | Baroque | Modernist | Contemporary |

| 5 euros | 10 euros | 20 euros | 50 euros | 100 euros | 200 euros |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classic | Romanesque | Gothic | Renaissance | Baroque | Modernist |

History

The Treaty on European Union, which entered into force in 1993, provides for the creation of an Economic and Monetary Union with the introduction of a single currency. The countries that meet a series of conditions would be part of it; would be introduced gradually. The originally scheduled date was delayed. Finally, the member states of the European Union agreed on December 15, 1995 in Madrid to create a common European currency –under the name euro– with a date of entry into circulation in January 2002..

The first step in the introduction of the new currency was officially taken on January 1, 1999, when the currencies of the eleven countries of the Union that took advantage of the single currency plan ceased to exist as independent systems, the so-called euro zone: Austria, Belgium, Spain, Finland, France, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Portugal and other countries outside the European Union such as Vatican City, Monaco and San Marino that they adopted the currency through agreements that they maintained with countries of the European Union (France in the case of Monaco, and Italy in the cases of Vatican City and San Marino) on behalf of the latter. These agreements have been renegotiated with the European Union. On January 1, 2001, Greece joined. However, due to the manufacturing period required for the new banknotes and coins, the old national currencies, despite having lost their official listing on the foreign exchange market, remained as a means of payment until January 1, 2002, when they were replaced by euro banknotes and coins. Both the coins and the banknotes had a period of coexistence with the previous national currencies until they were totally withdrawn from circulation. This period of coexistence had different calendars in the countries that adopted the euro.

Denmark and Sweden have not adopted the single currency. Denmark rejected the euro in a referendum held on September 28, 2000, with a turnout of 86% and where 53.1 percent of voters demonstrated against the adoption of the euro. The Swedish referendum on September 14, 2003, days after the assassination of minister Anna Lindh, the driving force behind the adoption of the euro, resulted in just over 56 percent of the electorate voting against it. The issue is thus postponed for at least five years, after which the referendum may be repeated.

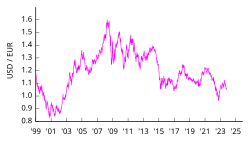

On January 1, 2002, the first day of circulation of the new European currency, 1 euro was exchanged for 0.9038 United States dollars (USD).

In July 2002, the euro surpassed parity with the dollar in the foreign exchange market for the first time since February 2000, and it has remained so.

On July 15, 2008, the euro reached its maximum value so far, exchanging 1 euro for 1.5990 dollars.

Since 2002, there have been three enlargements of the European Union, in which a total of thirteen countries have joined (ten countries in May 2004, two in January 2007 and one in July 2013). To date (2022), seven of those countries have adopted the euro as their currency.

On July 11, 2006, the Ministers of Economy and Finance of the European Union (ECOFIN) ratified the entry of Slovenia into the euro zone effective January 1, 2007.

On July 10, 2007, the finance ministers of the European Union gave their final approval to the incorporation of Malta and Cyprus to the euro zone as of January 1, 2008.

On July 8, 2008, the European Union's Ministers of Economy and Finance approved Slovakia's entry into the euro zone effective January 1, 2009.

On July 13, 2010, the European Union's finance ministers approved Estonia's entry into the euro zone effective January 1, 2011.

On June 30, 2011, Andorra, which has been using the euro de facto since its creation, signed a monetary agreement with the European Union that allows it to use the euro officially as well as to coin its own euro coins. This agreement entered into force on April 1, 2012. The scheduled date for Andorra to start minting its own euro coins was July 1, 2013. However, in October 2012, the delay of the issuance of euros until 2014 was announced. Finally, said issue took place in December 2014.

Finland and the Netherlands have withdrawn the 1 and 2 cent coins from circulation, as they cost more to manufacture than their face value. To do this, they have implemented a system whereby prices are not changed, but once at the checkout they are rounded up to 0 and 5 cents. Despite this, in these countries, the 1 and 2 cent coins are still legal tender and are issued for collection sets.

In May 2013, the European Commission raised the possibility of withdrawing the 1 and 2 euro cent coins from circulation because the production costs exceed their value and have caused accumulated losses of 1.4 billion euros from 2002 to the eurozone. These costs would advise, according to Brussels, to stop minting 1 and 2 cent coins. However, the Community Executive warned that this could cause a "negative reaction" among citizens due to the rounding of prices that it would cause. In addition to their withdrawal from circulation, the Commission suggested three other possible scenarios for the future of the 1 and 2 cent coins: keep the current situation, continue minting them but at a lower cost and stop issuing them but allow them to continue to be used.

On July 9, 2013, the European Union's finance ministers approved Latvia's entry into the euro zone on January 1, 2014.

On July 23, 2014, the Council of the European Union approved Lithuania's entry into the Eurozone on January 1, 2015.

On May 4, 2016, the governing council of the European Central Bank decided that the 500 euro banknote would cease to be produced at the end of 2018, excluding it from the new "Europa" banknote series, but that it is still a legal form of payment. This was due to concerns that this note could facilitate illegal activities.

On July 12, 2022, the Council of the European Union authorized Croatia to adopt the euro on January 1, 2023.

Usage

The euro is used in the 20 countries of the European Union that have adopted it (Germany, Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Croatia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Estonia, Finland, France, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands and Portugal). This group of countries is called the eurozone (or euro zone). It should be borne in mind that the French overseas departments of French Guiana, Guadeloupe, Martinique, Mayotte and Réunion as well as the French overseas community of Saint Martin belong to the European Union and use the euro as their currency.

The French overseas communities of Saint Barthélemy and Saint Pierre and Miquelon, as well as the French Southern and Antarctic Lands and Clipperton Island (the latter two uninhabited), do not belong to the European Union but also use the euro as their currency.

The European microstates of Andorra, Vatican City, Monaco and San Marino use the euro and mint their own currencies under agreements signed with members of the European Union (France in the case of Monaco, and Italy in the case of Vatican City and San Marino) as the latter. These agreements were renegotiated with the European Union, so that on January 1, 2010 the new agreement entered into force with Vatican City, on December 1, 2011 with Monaco and on August 1, 2012 with San Marino. As for Andorra, it signed a monetary agreement with the EU on June 30, 2011, which entered into force on April 1, 2012, but did not mint euros until December 2014.

Montenegro and Kosovo also use the euro, without entering into any legal agreement with the European Union, replacing the deutsche mark they previously used.

The sovereign bases of Akrotiri and Dhekelia, a British territory on the island of Cyprus, had the Cypriot pound as their official currency before Cyprus' entry into the eurozone in 2008, the date on which these bases became the first territory British to adopt the euro.

Finally, note that in border areas with the euro area, as well as in tourist areas of many European countries that do not belong to the euro area, the euro is usually accepted in shops and even on public transport. It is also accepted in numerous countries around the world in a similar way to the US dollar.

Currencies linked to the euro

There are two currencies linked to the euro through the European exchange rate mechanism. They are the following:

- Bulgaria has the Bulgarian leva tied to the euro with a exchange rate of 1,95583 Bulgarian leva = 1 euro and a fluctuation band of ± 15%.

- Denmark has the Danish crown tied to the euro with a exchange rate of 7,46038 Danish kronor = 1 euro and a fluctuation band of ± 2.25 %.

On the other hand, the currencies of other countries and territories that were linked to the European currencies that disappeared when the euro was created, became linked to it. They are the following:

- Bosnia and Herzegovina: the convertible framework was linked to the German framework. Currently, it has a fixed exchange rate of 1,95583 convertible frameworks = 1 euro.

- Cape Verde: the Cape Verdean shield was linked to the Portuguese shield. Currently, it has a fixed exchange rate of 110,265 Cape Verdean shields = 1 euro.

- Comoros: the Comorian franc was linked to the French franc. Currently, it has a fixed exchange rate of 491,96775 Comorian francs = 1 euro.

- Central African Economic and Monetary Community (Cameroon, Chad, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, the Central African Republic and the Republic of the Congo): the Central African CFA franc was linked to the French franc. Currently, it has a fixed exchange rate of 655,957 CFA francs in Central Africa = 1 euro.

- North Macedonia: the Macedonian denar was linked to the German frame. Currently, it is linked to the euro.

- West African Economic and Monetary Union (Benin, Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Niger, Senegal and Togo): the West African CFA franc was linked to the French franc. Currently, it has a fixed exchange rate of 655,957 CFA francs in West Africa = 1 euro.

- The French overseas communities of French Polynesia and Wallis and Futuna as well as the special collectivity of New Caledonia: the CFP franc was linked to the French franc. Currently, it has a fixed exchange rate of 119,3317 CFP = 1 euro.

In addition, the currency of Sao Tome and Principe (the Sao Tome dobra) is linked to the euro following an agreement signed with Portugal in 2009 and entered into force on January 1, 2010. It has a fixed exchange rate of 24,500 dobras santotomenses = 1 euro.

Therefore, within the European Union two countries have currencies linked to the euro through the European exchange rate mechanism (Bulgaria and Denmark); while outside the European Union a total of 22 countries and territories have currencies linked to the euro: 14 countries in continental Africa (Cameroon, Chad, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, the Central African Republic, the Republic of the Congo, Benin, Burkina Faso, Costa of Ivory, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Niger, Senegal and Togo), 3 countries in insular Africa (Cape Verde, Comoros and Sao Tome and Principe), 2 countries in the Balkans (Bosnia-Herzegovina and North Macedonia) and 3 territories Pacific French (New Caledonia, French Polynesia and Wallis and Futuna).

Belarus and Morocco have their respective currencies (the Belarusian ruble and the Moroccan dirham) pegged to a basket of currencies made up of the euro and other currencies. On the other hand, in Zimbabwe, the euro is used along with other currencies since the disappearance of the Zimbabwean dollar.

In addition, different countries (such as Switzerland or the Czech Republic) have had or have the euro as a reference in establishing their monetary policies, which leads their central banks to intervene in the markets currency.

Members of the EU outside the eurozone

Denmark negotiated a series of exit clauses from the Treaty on European Union after it was rejected in a referendum held in 1992. Thus, Denmark obtained exceptions in four areas (joint defense, common currency, judicial cooperation and European citizenship). Finally, the modified treaty was accepted in another referendum held in 1993. On September 28, 2000, a referendum on the adoption of the euro was held in Denmark, resulting in 53.2% against joining the single currency. In 2015, a referendum on the abolition of the four exit clauses discussed again resulted in a "no".

Sweden has no formal exit from the monetary union (the third stage of EMU) and therefore should, at least in theory, adopt the euro at some point. On September 14, 2003, a referendum was held on the adoption of the euro, but the initiative was rejected with 56% of the vote. The Swedish government often argues that it is possible not to adopt the euro even if there is an obligation to do so because one of the requirements to be part of the eurozone is to have previously belonged to the ERM for two years. By simply choosing to opt out of such a mechanism, the Swedish government has an informal clause on the adoption of the euro.

The 10 members that joined the European Union in 2004 are also required, by the treaties that allowed them to enter, to end up adopting the euro in the future.[citation required] Slovenia, Cyprus, Malta, Slovakia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Croatia have already adopted it. Some dates were established in which these states had to complete the third stage of the Economic and Monetary Union of the European Union: 2007 for Slovenia, Estonia and Lithuania; 2008 for Cyprus, Latvia and Malta; 2009 for Slovakia; and 2010 or later for Hungary, Poland and the Czech Republic. The reality is being different: as already indicated, in 2007 only Slovenia adopted the euro; in 2008 Cyprus and Malta adopted it; in 2009, Slovakia; in 2011, Estonia; in 2014, Latvia; in 2015, Lithuania and in 2023, Croatia.

Similarly, the new states that have joined the European Union since 2004 are also obliged to adopt the euro in the future. Therefore, Romania and Bulgaria, which joined the European Union in 2007, will have to adopt it.[citation needed] Croatia, which joined on July 1, 2013, will did in 2023.

Potential adoptions

Former members of the EU

The United Kingdom, like Denmark, also had a clause that it was not obliged to adopt the euro. British eurosceptics believed that a single currency was merely a step towards the formation of a unified European superstate and that removing Britain's ability to determine its own interest rates would have had dramatic effects on its economy. The contrary view was that since intra-European exports accounted for 60% of total British exports, exchange rate risk would have been reduced. Gordon Brown, Chancellor of the Exchequer under Tony Blair, set out "five economic tests" that he should pass before recommending the entry of the United Kingdom into the euro; and promised to hold a public referendum to decide membership in the eurozone. In addition, the three main British political parties have promised to call a referendum before joining the euro. The coalition government elected in 2010 pledged not to join the euro during the legislature. The adoption of the single currency has always been a very complicated issue due to the significant Euroscepticism that exists in the United Kingdom, mainly in England, and in which a large part of the population has always been against the adoption of the euro. After the departure of the United Kingdom from the European Union, as a consequence of the referendum on the permanence of the United Kingdom in the European Union held in 2016, the hypothetical adoption of the euro by the United Kingdom was no longer possible.

Effects of a single currency

The introduction of a single currency for many separate states presents a number of advantages and disadvantages for the participating nations. Opinions differ on the effects of the euro thus far, as many of them will take years to understand.[citation needed]

Elimination of exchange rate risk

One of the most important benefits of the euro will be the reduction of exchange rate risks, which will make it easier to invest across borders. Changes in the relationship between currencies have typically brought risk to companies and individuals when investing or even importing or exporting outside of their own currency zone. Gains can be quickly wiped out as a result of currency rate fluctuations. Therefore most investors and importers/exporters have to either accept the risk or "hedge" by having several options available, resulting in higher costs in the financial market. Consequently, it is less attractive to invest outside the zone of the currency itself. The eurozone greatly increases the investment area without exchange rate risk. As the European economy is heavily dependent on intra-European exports, the benefits cannot be underestimated. This is particularly important for countries whose currencies have traditionally fluctuated significantly.

Elimination of conversion costs

One of the main benefits is the elimination of costs associated with banking transactions between currencies, which previously constituted an expense for both individuals and companies when they changed from one currency to another. It is difficult to quantify this cost, but some sources put it at approximately 0.5% of GDP.[citation needed]

Deeper Financial Markets

The introduction of the euro is expected to bring flexibility and liquidity to financial markets that were previously lacking. An increase in competition and the availability of financial products through the union is also expected to reduce their costs for companies and possibly also for individual consumers. The costs associated with public debt will also decrease.[citation needed]

It is also expected that the greater breadth of financial markets will lead to an increase in capitalization and stock market investment. All of this favors transnational business concentrations within the Eurozone, facilitating the emergence of larger and more competitive financial and business institutions.[citation required]

Loss of autonomous monetary policy

The creation of the single currency has meant a series of disadvantages for many countries that in the past adjusted the value of their currency to the different prevailing economic situations. Thus, the devaluation of the currency became an effective tool to stimulate the competitiveness of goods and services produced in a given country. The impossibility of carrying out these devaluations has been related to the persistence of the crisis in the countries of southern Europe, and there has also been speculation about the benefits of abandoning the euro and the recovery of the drachma, with the consequent recovery of monetary autonomy, they might have for Greece.

Starting in 2009, as a result of the international financial crisis, there was speculation about the possibility that a country could abandon the common currency. After the Greek financial crisis and the subsequent European sovereign debt crisis, such speculations increased, especially in the case of Greece.

The euro and other currencies

United States, United States dollar control zone Areas outside the U.S. U.S. dollars used Coins linked to the US dollar Coins tied to the US dollar with broadband

Euro/dollar ratio

The euro represents an alternative to the US dollar for several reasons:

- Economic reasons: the euro began to quote on 4 January 1999 at the price of 1,1789 US dollars (USD). On 27 January 2000, it lost parity with respect to that currency for the first time in its history that it again surpassed 22 February 2000. January 1, 2002, first day of circulation of the new European currency, 1 euro changed by 0.9038 dollars. On 15 July 2008, the euro reached a quote on the dollar $1.5990the maximum value of change since its introduction. On the other hand, in December 2006 it moved to the dollar as the most used currency for cash payment. That month, around 614 billion euros were circulating around the world, while the dollars totaled 588 billion in euros. In addition, it must be borne in mind that the euro is the currency of the first world economic power and that the European economy is healthier than the American economy, which makes it a safer and stronger currency than the US dollar. However, following the rejection in the referendum of France and the Netherlands to the European Constitution and the uncertainty, therefore generated with respect to the future of the Union, the euro slowed down in its boom and depreciated (although it remained higher than the dollar); the state of which it subsequently recovered. In recent years, due to the European sovereign debt crisis, there have been ups and downs in its shift over the dollar. As of 25 January 2023, the euro is listed at the price of $1,091.

- Political motives: Some states favor the use of the euro, harming the dollar, because they disagree with the policy that the United States takes on such issues as the economy or international diplomacy, and which, in many cases, does not mean having a pro-European stance, but an anti-American stance. Some examples are Cuba, Iraq or North Korea. Cuba forbade the US dollar to be used in its territory from 8 November 2004 and any dollar that enters Cuba must be changed to Cuban convertible peso, with a tax of 10%, tax that does not have the euro, or other currencies such as the Swiss franc. Regarding Iraq, before it was invaded by the United States, it changed the dollars for euros, some social sectors saw in this change one of the reasons why George W. Bush was interested in intervening in Iraq, and thus re-establishing the U.S. dollar in that Arab state and preventing the OPEC from changing to the euro, a fact that would have nefarious consequences for the U.S. economy, in addition to ending the hegemony of the dollar. In 1998, Cuba announced that it would replace the US dollar with the euro as its official currency for the purposes of international trade. North Korea, since December 2002 and Syria, since 2006, did the same. Similarly, China and Russia have transferred much of their currency reserves from the dollar to the euro.

| Current EUR exchange rate | |

|---|---|

| Google Finance Data: | AUD CAD CHF GBP HKD JPY USD |

| Yahoo data! Finance: | AUD CAD CHF GBP HKD JPY USD |

| XE.com data: | AUD CAD CHF GBP HKD JPY USD |

| OANDA.com data: | AUD CAD CHF GBP HKD JPY USD |

| fxtop.com data: | AUD CAD CHF GBP HKD JPY USD |

Controversy over hidden euro inflation

There is an interpretation of the ECB's monetary policy, according to a widespread opinion among the inhabitants of the euro zone that proposes the hypothesis that the introduction of the euro as the single currency of the European Union has caused an increase in inflation, especially in the middle and low income classes, much higher than that registered by the official inflation indices published by the member states. This perception has been the subject of some important sociological studies. According to these same studies, people began to perceive this increase shortly after the end of the period of dual circulation of the euro with national currencies, and it continues to this day.

Penetration into public opinion of this opinion

The extent of this state of opinion is evidenced by the numerous entries that can be found in the Google search engine introducing the terms «hidden inflation» + euro (36 on October 17, 2007) and «hidden inflation + euro» (229) and the equivalents in other languages such as "inflation cache" and "covert" or "hidden" inflation. (See external links). A good example of this is the number of interventions that exist in blogs on this particular topic. There are some journalistic reports that reflect this concern of some citizens of the euro zone. Many consumer associations defend this idea. An example is the spokesperson for the Spanish consumer association (UCE-UCA).

Arguments and associated opinions

There is also the opinion, and even a multitude of analyzes that have appeared in important meetings and academic publications, that macroeconomic indices are systematically manipulated by governments in order not to lose popularity, and this could facilitate the appearance of political cycles of budget in the euro area, or make the population accept measures that would be unpopular if their scope were known with absolute transparency. On the other, it is criticized that the "psychological effect" of the currency exchange on prices, underestimating it in such a way that the correct discrimination of the same was prevented.

Thus, since the update of salaries is carried out based on the CPI, which according to the opinion-makers is manipulated to give a lower figure than the real one, the result, according to this opinion, was a net transfer between the lower strata poor towards the richest, for which reason it is speculated that the effect was allowed to take place, or at least it is a cover-up by pressuring the media so that the issue is not discussed, or whoever does is discredited.

Financial analyst Jim Puplava, in a recent article, admits that there exists worldwide, on the part of all governments (he analyzes the United States in particular) a situation in which a "manipulation is intentionally created statistic that was intended to control the government deficit and create an illusion designed to calm the markets and distract them from a reality where inflation is growing.”

Possible amount of inflation

Regarding the perception of citizens, in the example of Spain, there is a belief that in the most basic consumption, of products with a cost of between 1 and 10 euros, the prices established after the entry into circulation of the euro rose to reach the level of 100 pesetas = 1 Euro, which represents a little more than 66% inflation. In Germany some authors approximate these figures to 50%. Actually, it is possible, according to these opinions, that inflation would rise much more, if we made a real composition of the shopping basket and current expenses in average incomes. In Italy, a special commission has been created to study the composition of prices because, according to some, goods for daily consumption should not be considered within the inflation index with the same weight as those that involve a long-term outlay term. In particular, supporters of this opinion point to the following reasons:

- Income for the purchase and acquisition of the house has risen due to an increase of more than two digits in the price of the same few quarters, and figures close to 10% most of them.

- The fuels have had a minimum rise of more than 4% per year.

- General food has risen by 100% in many basic foods in the six years following the introduction of the euro.

- Hospitality and leisure (an important chapter of family spending in Spain) has made rises of prices much higher than the above-mentioned equivalence.

- It seems that only the rise of articles related to electronics and automotive has been contained.

Consequences

As a consequence of this perception, according to those who think so, there could be a decline in the Europeanist spirit of the EU population, and perhaps be responsible for the rejection by France and the Netherlands of the European constitution in a referendum. The matter opens a debate on the transparency and legitimacy of the decisions of the European Council on macroeconomic policies and other policies, and the lack of citizen control over the organs of power of the Union. Some authors like Sandell think that the perception of the existence of hidden inflation due to the euro may be behind the refusal of Sweden and other countries to adopt the Euro as their currency.

The controversy in Italy: citizen commission

Due to the controversy over the level of inflation, a "study commission for the calculation of price indices" has been activated in Italy, made up of university professors, statisticians, representatives of social actors (unions and Confindustria) and representatives of consumer associations.

Support for Nicolas Sarkozy's thesis

The edition of the newspaper El País of August 31, 2007 includes some statements by the former president of France, Nicolas Sarkozy, at the Medef summer university (the main French employers' association, equivalent Spanish CEOE), attacking the ECB's policy with statements such as "denying the rise in prices after the entry of the euro is "laughing at people"" and "saying that the entry into force of the euro has not led to a rise in prices is laughing at the world”, at the same time that he demands “that there be a debate on the level of interest rates”.

Contrary opinions

Some analysts, such as Rickard Sandell, believe that the so-called "hidden inflation of the euro" it is a myth. Although looking at official sources, such as Eurostat, Sandell refers to the fact that not all the countries of the European Union have suffered inflation. Specifically, eight of the fifteen members of the European Union after the introduction of the euro showed a moderate decrease in inflation, and another seven a moderate increase. Such data leads to qualifying hidden inflation as a "myth".

Used bibliography

- Joseph E. Stiglitz, The euro: How the common currency threatens the future of Europe, editor 'Penguin Random House Editorial Group Spain', 2016, ISBN 8430618279 and 9788430618279 (partial text online).

Contenido relacionado

Dependent territory

Racism

Small property