Estonia

Estonia, officially the Republic of Estonia (Estonian: Eesti Vabariik), is one of twenty-seven sovereign states that form the European Union, being the smallest of the three Baltic countries. It borders Latvia to the south, Russia to the east, the Gulf of Finland to the north, and the Baltic Sea to the west.

The territory of Estonia comprises a continental region and a set of 2,222 islands and islets within the Baltic Sea, covering a total of 45,228 km². It is politically divided into 15 counties, and the country's capital is its largest city, Tallinn. With a population of 1.3 million, Estonia is one of the least populated countries within the European Union.

The Estonian people are ethnically and linguistically sister to the Finns and have historical and cultural ties to the Nordic countries as well as the other two Baltic countries. Despite this, the Nordic countries have not yet recognized their affiliation to this group, although they are in negotiations to join the Nordic Council, in which the Baltic republics are officially observers.

Estonia adopted the euro on January 1, 2011, replacing the Estonian kroon.

History

Prehistory and Antiquity

The earliest settlement in Estonia appears to date back to the melting of the last ice age approximately 13,000 years ago. The oldest known settlement is the settlement of Pulli, on the banks of the Pärnu River, near the present-day city of Sindi, in southern Estonia. According to radiocarbon tests, it dates to 11,000 years ago, at the beginning of the 11th millennium BCE. c.

Remains of stone and bone utensils belonging to hunting and fishing communities have been found near the town of Kunda in northern Estonia, dating back to 6500 BC. C. The Kunda culture belongs to the Mesolithic period and also extends to northern Latvia and southern Finland.

Estonia was populated by peoples of the Finno-Ugric group since prehistoric times; the date is unknown although it is assumed that these groups would have been present at least in the first millennium BC. C. The end of the Bronze Age and the beginning of the Iron Age was a period marked by great cultural changes. The most significant was the emergence of agriculture, which has continued to form the basis of the Estonian economy and culture. Agriculture expanded between the 5th and 1st centuries B.C. C. and the population grew. Cultural influences from the Roman Empire also reached Estonia in this period, which is known as the Roman Iron Age.

During the Iron Age, there were attacks from Baltic tribes, who entered the country both by land and by sea. There are several Scandinavian sagas referring to these campaigns against Estonia. Estonian pirates also made similar raids, for example taking part in the looting and burning of the Swedish city of Sigtuna in 1187.

Middle Ages

At the beginning of the 13th century Estonia was divided into eight large counties: Saaremaa, Läänemaa, Rävala, Harju, Viru, Järva, Sakala, Ugandi and other smaller counties. Through a meeting of representatives from several counties, a State was established in which a pagan religion centered on the Tharapita deity was professed. In the course of that century, Germans and Danes brought the country under their influence. The military order of the Livonian Brothers of the Sword conquered southern Estonia, introducing Christianity.

In 1227 Denmark took possession of the north, which it would hold until 1346. Merchants from the Hanseatic League monopolized the trade in Estonian ports. In 1343, the population of the north and the island of Saaremaa rose up against the Germans in the St. George's Night Rising, which was suppressed and the rebel 'king' of Saaremaa, Vesse, was hanged in 1344. After the treaty from Marienburg (1347), Estonia is bought for 19,000 silver marks by the Teutonic Knights. Subsequently, Russian invasion attempts followed in 1481 and 1558.

The Teutonic Order, by embracing the Protestant Reformation in 1524, introduced Lutheranism to Estonia. The country will remain in the hands of the Teutonic Knights, although it formally belongs to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania until 1561, the year in which Sweden takes over the country, although respecting the existence of the German feudal landowners.

Modern Age

In 1561, the district of Reval (present-day Tallinn) voluntarily placed itself under Swedish protection, and as a result of the Livonian War (1558-1582), northern Estonia is under Swedish rule, while the south passes to Poland for a brief period in the 1580s. In 1625, the entire territory came under the Swedish kingdom. Estonia was administratively divided between the provinces of Estonia in the north and Livonia, which also included southern Estonia and northern Latvia, a division that lasted until the beginning of the century XX.

In 1631, the Swedish king Gustav II Adolf forced the nobility to grant greater rights to the peasantry, although serfdom continued to exist. The following year a printing press was opened and the university was founded in the city of Dorpat (present-day Tartu); this period is known in Estonian history as 'the good old Swedish days'.

After the Great Northern War (1700-1721), the Swedish empire lost Estonia to the Russians (in 1710 de facto, and in 1721 through the Treaty of Nystad). However, the upper class and upper-middle class will remain primarily of Baltic-German origin. The war decimated the Estonian population, which would quickly recover. And although the rights of peasants were initially weakened, serfdom was abolished in 1816 in the Estonian province and in 1818 in Livonia.

19th century

As a result of the abolition of serfdom and progressive access to education for the native Estonian-speaking population, XIX a strong nationalist movement, which manifests itself initially at the cultural level, in which Estonian literature, theater and music develops, contributing to the formation of Estonian national identity. Among the leaders of the movement stood out Johann Voldemar Jannsen. Some important achievements of this movement will be the publication of the national epic, Kalevipoeg, in 1862, and the organization of the first national song festival in 1869. The University of Tartu was the main focus of these movements.

In response to the period of Russification, ushered in by the Russian Empire in 1890, Estonian nationalism took on more political overtones, with intellectuals calling first for greater autonomy and later for independence from the Russian Empire.

Independence and World War II

In 1904, Estonian nationalists took over Tallinn, displacing the German-born rulers. After the fall of Tsar Nicholas II of Russia, in March 1917, a demonstration of 40,000 Estonians in Petrograd forced the Provisional Government to grant them autonomy. In November 1917, in the election for a Constituent Assembly, the Estonian Bolsheviks only obtained 35.5% of the vote, so they proceeded to seize power by force. On February 24, 1918, Estonia declared its independence. independence from Russia and installed a provisional government, but the Germans occupied Tallinn and the Estonian government was forced into exile.

After the defeat of Germany in World War I and the remnant of the United Baltic Duchy, the Estonian War of Independence began. In February 1919, the Estonians defeated the Red Army and in November of the same year the German mercenary troops, installing the Provisional Government of the Republic of Estonia. On February 2, 1920, the young Russian SFSR recognized the military defeat and independence of the country by the Treaty of Tartu. A year later, Estonia entered the League of Nations. In the 1930s Estonia went from a parliamentary democracy to a quasi-dictatorial regime in 1933. The Riigikogu (Estonian Parliament) was dissolved in 1934, and in 1937 it was transformed into a presidential-parliamentary system, whereby the country was governed by decrees by Konstantin Päts, president since 1938.

The secret Additional Protocol to the Soviet-German Pact, signed on August 23, 1939 by Foreign Ministers Molotov and Ribbentrop, established that Estonia and its two Baltic neighbors, Latvia and Lithuania (in addition to Finland), would remain in the area of soviet influence. At the same time, Tallinn signed a mutual assistance treaty with Moscow that included the installation of Soviet naval bases and the presence of 25,000 Red Army soldiers on Estonian territory.

In June 1940, after giving an ultimatum and demanding the entry of troops into Estonian territory, due to the alleged disappearance of soldiers, Stalin deposed the Tallinn government and replaced it with members of the Estonian Communist Party, who He assumed power after elections held in the midst of the occupation, without democratic guarantees, since only candidacies related to the communists were allowed. The new government adopted the name of the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic and was incorporated into the USSR.

The United States, the United Kingdom and other Western countries considered this annexation an illegal act (following the Stimson doctrine), so they continued to maintain diplomatic relations with the representatives of the Estonian government in exile, and did not recognize the Estonian SSR as part of the Soviet Union. This fact was used as a basis for the subsequent claims of independence in the last years of the USSR.

When Operation Barbarossa against the USSR began, about 34,000 Estonian youths enlisted in the Red Army. Less than 30% of them survived the war. Hundreds of political prisoners, who the Soviet authorities were unable to evacuate due to the collapse of the railway system, were executed.

Between 1941 and 1944, Estonia was occupied by Nazi Germany. Most Estonians saw the Germans as liberators who would take them out of Soviet hands. When everything was forged and the war ended, the Germans would restore their independence, thus granting them this degree of autonomy lost and taken away by the Soviets. The Baltic States were for the time being incorporated into the German province of Ostland and ruled directly by Berlin, changing the local currency and introducing the German mark for the time being for greater economic sustainability in times of war.

Many Estonians volunteered in Finland, forming the 200 AKA Finnish Army Infantry Regiment (Estonian: soomepoisid, 'the boys from Finland') in the fight that the Finns and Germans they held against the Soviets. In 1944 Finland withdrew from the war and the soldiers of the 200 Regiment returned to Estonia to continue the fight, many of whom enlisted for the German armed forces (including the Waffen-SS). After the Battle of Narva, Soviet forces reoccupied Estonia in the fall of 1944. Faced with the imminent occupation, 10,000 Estonians decided to flee together with the Germans to Finland and Sweden. Given Estonia's help to the Nazi regime in the fight against the Soviets in the Baltic region, this has been controversially denounced by the Simon Wiesenthal Center, which has accused Estonia of not openly condemning the Nazi regime, of not collaborating in the persecution of Germans and to defend Nazism as a liberator trying to minimize Nazi atrocities. Also from Estonia, this complaint was responded to by answering that they collaborated with Nazism and together with Finnish troops to try to prevent the Soviets from invading and occupying their respective nations.

Many expert historiologists believe that the events that occurred during the Second World War in Estonia have always been misrepresented and very partial in many current media when it comes to telling what really happened. Always putting Estonia under suspicion of alleged German collaboration, whose interests were none other than the liberation of her own state.

Soviet period

The Soviet regime implemented industrialization and forced collectivization of the countryside. The German minority was expelled, as was the Swedish. Some 80,000 Estonians immigrated to the West and around 20,000 were deported between the years 1945 and 1946.

Russian colonization, coupled with the demographic ravages of war, altered the traditional ethnic composition of the population. The third wave of mass deportations took place in 1949, when an estimated 40,000 more Estonians were sent to Siberia, mostly farmers resisting the forced collectivization imposed by the authorities. Half of those deported died, while the other half could not return until the 1960s. This situation gave rise to the formation of a guerrilla group in the 1950s against the Soviet authorities in Estonia, the "forest brothers", made up of mainly by Estonian and Finnish veterans, as well as some civilians.

Another aspect of Soviet rule was militarization. Most of the coast and all the islands were declared 'border areas', and access by non-residents was made conditional on obtaining a safe-conduct. An important military installation was the city of Paldiski, which in 1962 became a training center for nuclear submarines for the Soviet Navy. With its two land-based nuclear reactors, and its 16,000 people employed, it was the largest facility of its kind in the entire Soviet Union. The Russification of Estonia also developed: during the 45 years of occupation, approximately half a million Russian-speakers were transferred to Estonia by the administration to implement industrialization and militarization. In this context, during the 1980 Moscow Olympic Games, there were protests in the city of Tallinn (where the regattas took place) against the immigration policy of the Soviet Union.

Economically, Soviet domination had a negative impact on Estonia's economic growth, being almost zero compared to other neighboring economies, such as Finland or Sweden, with which Estonia was on a par before the start of the World War II.

Under Perestroika, nationalist demonstrations multiplied from 1986, promoted by the group for the defense of human rights Charter 1987. The Estonian Popular Front, created on October 1, 1988, channeled nationalist aspirations and triumphed in the elections for the Congress of People's Deputies of the Soviet Union (March 26, 1989), and Estonian replaced Russian as the official language.

In August 1989, some two million Estonians, Latvians and Lithuanians formed, in the largest demonstration of the Singing Revolution, a human chain of more than 560 km, from Tallinn to Vilnius, to demand the independence of the Baltic States. Moscow accepted the economic autonomy of the republic on November 27.

Independence

A convention of Estonian representatives approved in February 1990 the Declaration of Independence based on the Treaty of Tartu. The FPE and other nationalist groups won a large majority in parliament in the May 1990 elections. The moderate nationalist leader Edgar Savisaar presided over the first elected government since 1940. On 8 May the name "Republic of Estonia" is re-adopted. and the restoration of independence is proclaimed, postponed and declared illegal by Moscow, but ratified in a referendum in March 1991. After the events of August 1991 in the Soviet Union, the parliament proclaimed independence again on August 20 under the threat of Soviet tanks. Independence was first recognized by Iceland and soon followed by the countries of the European Community and the United States. It was accepted by the Soviet Union on September 6, 1991. Estonia joined the UN and the CSCE and established the crown as the monetary unit.

In January 1992, Savisaar and his government resigned amid mounting criticism of his economic policy. Parliament then appointed former Transport Minister Tiit Vahi as the new president. Estonia had to ration food and fuel consumption as Russia applied restrictions and raised the price of its products.

On June 20, 1992, a referendum ratified the Fundamental Law (based on the 1938 law). In September the Riigikogu (Estonian Parliament) was elected. On October 5, Lennart Meri was elected President of Estonia at the head of a coalition. Two days later the new Constitution entered into force.

In June 1993, a serious conflict occurred when a rigorous nationalist statute was approved, which restricted the civil rights of the Russian minority (30% of the total). Russia reacted by cutting off oil supplies, and Parliament amended the most controversial articles (July 8). Russian troops finished evacuating the country on August 31, 1994.

The coalition that had led Estonia since it left the former Soviet Union was defeated in elections in March 1995. The new prime minister, Tiit Vahi, sparked controversy over the number of ex-communists in his government. In October his cabinet had to resign due to accusations of corruption against the interior minister. A new government was formed with members of the Reform Party (PR).

Mart Laar was appointed prime minister in March 1999. After the problems with the Russian minority were overcome, Estonia and Russia signed a bilateral trade and economic cooperation agreement in April 2001. Alleging treason by the PR by granting this party the mayoralty of Tallinn to the opposition, Laar resigned from his post in January 2002. During his tenure, Estonia, in addition to being the former Soviet republic with the most solid economy, began negotiations to join the European Union.

In 2003, a plebiscite was held in which 66.9% of voters declared themselves in favor of joining the European Union.

The presidents of Estonia and Cyprus signed two cooperation agreements in January 2004, one on education and culture, and the other to combat organized crime. This was interpreted by international analysts as a new era in Estonian relations with the Mediterranean countries. Estonia joined NATO on March 29, 2004, and on May 1, 2004, it joined nine other countries as a full member of the European Union, bringing the total number of members of the Union to 25.

Following a confidence vote against the justice minister, due to questions about his handling of the anti-corruption program, Prime Minister Parts resigned in March 2005. In April, Andrus Ansip of the center-right Estonian Reform Party was appointed prime minister.

On May 9, 2006, Europe Day, the Estonian Parliament ratified the European Constitutional Treaty by a vote of 73 to 1. Thus, the country became the fifteenth member state to ratify the European Constitution. A week later, Estonia voluntarily withdrew from its 2007 Eurozone entry race due to high levels of inflation. Estonia adopted the euro on January 1, 2011.

Government and politics

Estonia is governed by the republican system of government, with a president elected for five years by the unicameral parliament. The government or executive power is exercised by the prime minister, appointed by the president, along with 14 other portfolio ministers.

The Legislative Power is exercised by the Riigikogu or State Assembly, made up of 101 members elected on the basis of the proportional system. Deputies are elected for a period of four years. For its part, the Judiciary is made up of courts of first and second instance, above which is the Riigikohus or National Court, with 19 life members elected by Parliament at the proposal of the President.

Estonia has become one of the first countries with electronic voting, both for presidential and parliamentary elections.

Law

The Constitution of Estonia is the fundamental law, establishing the constitutional order based on five principles: human dignity, democracy, rule of law, social status and Estonian identity. Estonia has a legal system of law based on the Germanic legal model. The judicial system has a three-tier structure. The first instance is the county courts, which handle all criminal and civil cases, and the administrative courts, which hear complaints about the government and local officials, and other public disputes. The second instance is the district courts, which handle appeals against first instance decisions.

The Supreme Court is the court of cassation, and also conducts constitutional review, it is composed of 19 members. The judiciary is independent, judges are appointed for life, and can only be removed upon conviction by a court for a criminal act. The Estonian judicial system has been rated as one of the most efficient in the European Union by the EU Justice Scoreboard.

Human Rights

In terms of human rights, regarding membership of the seven bodies of the International Bill of Human Rights, which include the Human Rights Committee (HRC), Estonia has signed or ratified:

Foreign Relations

Estonia was a member of the League of Nations from September 22, 1921, and became a member of the United Nations on September 17, 1991. Since the restoration of independence, Estonia has maintained close relations with the countries Western countries, and is a member of NATO since March 29, 2004, as well as of the European Union since May 1, 2004. In 2007, Estonia joined the Schengen Area, and in 2011 to the Eurozone. The European Union Agency for Large-Scale Computing Systems is based in Tallinn, which started operating at the end of 2012. Estonia held the Presidency of the Council of the European Union in the second half of 2017.

Since the early 1990s, Estonia has been involved in active trilateral Baltic States cooperation with Latvia and Lithuania, and Nordic-Baltic cooperation with the Nordic countries. The Baltic Council is the joint forum of the inter-parliamentary Baltic Assembly and the intergovernmental Baltic Council of Ministers. Estonia has established a close relationship with the Nordic countries, especially Finland and Sweden, and is a member of the Nordic-Baltic Eight (NB-8) uniting the Nordic and Baltic countries. Joint Nordic-Baltic projects include the Nordplus education program and mobility programs for business and industry and for public administration. The Nordic Council of Ministers has an office in Tallinn with branches in Tartu and Narva. The Baltic States are members of the Nordic Investment Bank, the Nordic Battlegroup of the European Union, and in 2011 were invited to cooperate with NORDEFCO in certain activities.

The start of the attempt to redefine Estonia as "Nordic" was seen in December 1999, when the then Estonian Foreign Minister (and President of Estonia from 2006 to 2016), Toomas Hendrik Ilves, gave a speech titled "Estonia as a Nordic Country" before the Swedish Institute of International Affairs, whose possible political calculation was a desire to distinguish Estonia from its slower-progressing neighbors to the south, which might have postponed Estonia's early participation in the enlargement of the European Union. Andres Kasekamp argued in 2005 that the relevance of identity debates in the Baltics diminished with their joint entry into the EU and NATO, but predicted that, in the future, the appeal of Nordic identity in the Baltics will increase and, finally, five Nordic countries plus three Baltics will become a single unit.

Other international organizations to which Estonia belongs are the OECD, the OSCE, the WTO, the IMF, the Council of the Baltic Sea States, and on June 7, 2019 it was elected a non-permanent member of the Security Council of Estonia the United Nations for a term beginning on January 1, 2020.

Relations with Russia remain generally cool, although there is some practical cooperation.

In 2022, Russian planes were subject to an airspace ban as a penalty for invading Ukraine. This move was also made by several other nations.

Defense

The Estonian Defense Forces are made up of land, naval and air forces. Current national military service is compulsory for able-bodied males between the ages of 18 and 28, with conscripts serving 8- or 11-month shifts, depending on their education and the position they are provided by the Defense Forces. The size of the Forces Estonian Defense Force in peacetime is about 6,000 people, half of whom are conscripts. The planned size of the Defense Forces in wartime is 60,000 people, including 21,000 people in the high readiness reserve. Since 2015 the Estonian defense budget has been above 2% of GDP, meeting its NATO defense spending obligation.

The Estonian Defense League is a voluntary national defense organization under the direction of the Ministry of Defence. It is organized on the basis of military principles, has its own military equipment, and offers its members various types of military training, including in guerrilla tactics. The Defense League has 16,000 members and another 10,000 volunteers in its affiliated organizations.

Estonia cooperates with Latvia and Lithuania in several trilateral defense cooperation initiatives in the Baltic. As part of the Baltic Air Surveillance Network (BALTNET), the three countries manage the Baltic airspace control center, the Baltic Battalion (BALTBAT) has participated in the NATO Response Force, and in Tartu is located a joint military educational institution, the Baltic Defense College.

Estonia joined NATO in 2004. The NATO Cooperative Cyber Defense Center of Excellence was established in Tallinn in 2008. In response to Russian military operations in Ukraine, since 2017 the Forward Presence battalion battlegroup of NATO is based at the Tapa Army Base. Also part of the NATO Baltic Air Police deployment has been based at Ämari Air Base since 2014. In the European Union, Estonia participates in the Nordic Battlegroup and Permanent Structured Cooperation.

Since 1995, Estonia has participated in numerous international security and peacekeeping missions, including: Afghanistan, Iraq, Lebanon, Kosovo and Mali. The maximum strength of the Estonian deployment in Afghanistan was 289 soldiers in 2009. 11 Estonian soldiers have been killed in missions in Afghanistan and Iraq.

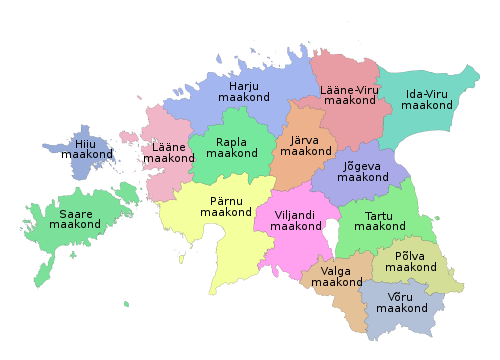

Political-administrative organization

The country is divided into 15 counties (Estonian: maakond, pl. maakonnad).

Geography

Estonia's territory includes a small piece of land on the southern shore of the Gulf of Finland and more than 1,500 islands in the Baltic Sea, including Saaremaa and Hiiumaa, located off the Gulf of Riga. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland and to the west by the Baltic Sea. To the east, Lake Peipus and the Narva River make up most of the border with Russia; to the south it borders Latvia, whose border is not based on any notable geographical feature.

It is larger than many European countries, such as Denmark or Switzerland. Its area is 45,228 km², similar, for example, to that of the Netherlands. Oil shale and limestone deposits, as well as forests that cover 47% of the territory, play a key role in the economy of the resource-poor country. Within continental Estonia there are also two distinct units: an area made up of low plains, located in the western half of continental Estonia and in the coastal strip of the Gulf of Finland, and another, somewhat higher, located in the eastern half. The Estonian coastline is very indented and its length is 3,794 km, of which 1,242 km are on the mainland and 2,540 km are divided between the islands. The coastline has numerous bays, straits and inlets and is mainly low-lying, except for the North Estonian cliffs and West Estonian cliffs on the northern coast of Saaremaa and Muhu islands.

Estonia is a very flat country with abundant wetlands. Its maximum height is Suur Munamagi, barely 318 m. Two large lakes stand out from its geography: Vorts and Peipus —the fourth largest in Europe. The climate is continental-humid, with mild summers and cold winters. The influence of the Baltic moderates the temperature and brings a lot of humidity. The island of Ruhnu in the center of the Gulf of Riga is the only island that does not lie within the coastal zone close to Estonia. It is situated 70 km southeast of Kuressaare. It has an area of 11.9 km². Its maximum altitude reaches it with the Haubjerre hill 29 meters above sea level. The coastline lacks the characteristic articulation of the rest of the Estonian islands. The islands occupy 9.2% of Estonia's land area and are characterized by being predominantly flat and forested. The largest islands are located in the western waters, within what is known as the Estonian archipelago.

Hydrography

Estonian hydrography is determined by climate and soil type. The continental Atlantic-type climate favors the rivers maintaining a rainfall feeding regime with a maximum volume in spring and a slightly smaller one in autumn.

Because the Estonian elevations are in the eastern half of the country and run from north to south, the rivers are divided into those running east-west, West Estonian River Basin, and those running West-East, Eastern Estonian River Basin. In the extreme southeast, the Koiva basin, which covers a small area, does not follow either of the two previous ones, but rather its rivers flow to the south. The heights of Pandivere constitute a veritable river source from where the main Estonian rivers flow.

Running from south to north, Estonia's main river basins are in the west, Parnu, Matsalu and Harju. And in the east, those of the Võrtsjärv, Peipus and Viru lakes.

- Pärnu watershed, its main river is the Pärnu and its tributary of this the Navesti, which flows into the Gulf of Riga.

- Matsalu watershed, its main river is the Kasari which flows into the sea of Väinameri.

- Watershed in Harju, its main rivers are the Javala and the Pirita that lead to the Gulf of Finland.

- Viru’s watershed, its main river is the Narva that flows into the Gulf of Finland.

- Peipus watershed, its main river is the Ema

- Watershed of the Võrtsjärv, its main river is the Väike Ema or Väike Emajõgi.

A defining characteristic of Estonian hydrography is the abundance of lakes, most of which are located in the south-east of the country. The number of lakes is greater than 1,400 if natural lakes and swamps are counted, and they account for 4.6% of Estonian territory. Most of them are small and have a surface area of less than 100 km², which only two lakes exceed, Lake Peipus, to the east, with 3,555 km², shared with Russia, and Lake Võrtsjärv or Võrtsjärv in the center, which with a surface area of At 270 km² it is the second largest lake in the country and the largest within national borders.

Climate

Estonia is located in the northern part of the temperate zone and in the transition zone between the Atlantic and continental climates, so both the influence of the Atlantic Ocean and that of the Eurasian continent interact to modify the climate. The warm current of the North Atlantic, which affects the Nordic countries, also influences Estonia.

In addition, at a more local level, the influence of the Baltic Sea causes significant differences between the coastal climate and the inland climate. Estonia has a temperate climate, with the four seasons of the year well differentiated and with the same duration. The average annual temperature in Estonia varies between 4.3 °C and 6.5 °C. The factors that most influence the local temperature, apart from latitude, are the distance to the sea and the relief. The temperature between the coast and the interior differs slightly in summer and more markedly in winter; Thus we have that in July, the warmest month of the year, the average temperature varies from 16.3 °C in the Baltic islands to 17.1 °C on the mainland, and in February, the coldest month in the islands. Baltic temperatures reach -3.5 °C on average, and -7.6 °C on the continent.

- Maximum temperature: 35.6 °C, Võru 11 August 1992.

- Minimum temperature: -43.5 °C, Jõgeva 17 January 1940.

Average rainfall is 568 millimeters per year; the greatest precipitations are the falls at the end of summer, lowering in autumn and winter. The areas that register the greatest amount of precipitation are the eastern highlands that are further from the coast. The maximum rainfall recorded in 24 hours was 148mm, the monthly maximum 351mm and the annual maximum 1157mm.

Economy

Given the negative economic growth of the first years of independence, caused in part by the difficulties of the transition to a market economy system, Estonia has bet on the liberalization of the economy: it stimulated foreign investment, privatizations and more cooperation with Finland. More than half of its foreign trade is with the European Union, which it joined in May 2004. Estonia's main exports are machinery, electronics, wood and textiles, Estonia is one of the largest exporters of wooden houses.

The privatization of companies is almost complete, only the port and the main power plants remain in the hands of the government. Estonia is mainly influenced by what happens in Germany, Finland and Sweden, its main trading partners.

Since 1996, the government has made a firm commitment to information technology, launching the Tiigrihüpe project to computerize schools and improve the population's access to technology. Estonia is at the forefront of Europe in Internet and mobile phone penetration, and the ICT sector today has great relevance in the country's GDP. However, its proximity to Russia and its constant friction due to problems with the population of Russian origin (25% of the total) make its geopolitical situation unstable and risky and discourage many investments. The small size of the country and its population hinder ventures that need more qualified human resources and many technology companies must migrate to other countries in search of them.

Tourism and transit trade also make important contributions to the economy. Finland and Sweden are among Estonia's most important partners in trade, investment and tourism. Estonia continues to be what the IMF describes as "exceptional among transition economies", watched over by a bilateral commission that ensures stable and strong growth, international payments, monetary stability and economic transparency. Estonia's stock market system is managed through OMHEX, the Baltic giant that controls the Tallinn and Helsinki stock exchanges, and Nokia, which have also jointly operated computer security since May 2001. In recent years, the Estonian economy has enjoyed a of the highest growth rates in the European Union.

Demographics

The Estonian Statistics Office estimated the country's population to be 1,329,000 in 2020. Of this group, 84.1% have Estonian nationality, 8.6% have another nationality (mostly, Russian citizenship) and 7.3% do not have defined citizenship. Life expectancy is 80 years and the national average age is 42 years, with negative natural growth (-1.5%) and a low birth rate (1.6 children per woman). After the fall of the Soviet Union, the country lost almost 15% of its population. Subsequently, it continued to decrease until 1,294,455 in December 2011, even lower than in the 1960s.

The population density (28 inhab./km²) is the lowest of the three Baltic republics. Approximately one third of the population lives in the metropolitan area of Tallinn, the capital of the country.

After the restoration of independence in 1991, the population has decreased due to the emigration of many citizens who came from other Soviet republics. Since the 2010s the figures have stabilized and have even recorded a slight upturn; Despite the negative natural growth, it has been motivated by the permanence of the Estonian natives and by the arrival of immigrants from the European Union.

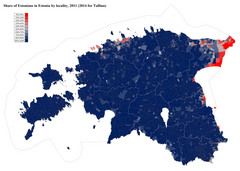

Ethnic composition

Citizens of Estonian origin make up 68.4% (909,552 inhabitants), while citizens of Russian origin make up 24.7% (327,802 inhabitants). The rest of the population is made up of minority groups of Ukrainians (1.9%), Belarusians (0.8%), Finns (0.6%) and other nationalities (3.6%). The population of Estonian origin predominates in the country as a whole, but that of Russian origin it accounts for a third of the total in Tallinn and is the majority in Ida-Viru County, on the north-eastern edge of the border with Russia.

Estonian society has traditionally been homogeneous; until the end of the 19th century Estonians accounted for 90% of the census and there was a significant minority of Baltic Germans (5%) and Russians (3%). After the German elite was replaced in the 1920s, the Russians became the main minority. Russian influence grew with the occupation of the USSR in 1940 and the constitution of the Estonian SSR, which led to the arrival of immigrants from other Soviet republics. During Stalinism there were also deportations of native Estonians. Although the Estonian population remained stable, with more total inhabitants it went from 88% of the census in 1934 to 61.5% in 1989. Since 1991 many citizens of Russian origin have left the country, but at a slower rate than in neighboring Latvia.

People without citizenship

The figure of "indefinite citizenship" (Estonian: kodakondsuseta isik) applies to emigrants from the Soviet Union and their descendants who have not obtained another nationality after the dissolution of the USSR For legal purposes they do not have the citizenship of any country, but they are not considered stateless either. In 2020 there were 69,993 people (approximately 7% of the population) under this legal figure, which came to represent more than 10% of the total in the 1990s and has been reduced thanks to the new naturalization policies.

After independence in 1991, the new state considered "Estonian of origin" only those born before June 17, 1940 (if they could prove it) and their descendants, since the invasion of Estonia took place on that date. Soviet Union. Estonians with indefinite citizenship have been entitled since 1996 to a gray "foreigner's passport" (välismaalase pass) that allows them to travel through the Schengen area and Russia without a visa, up to a maximum of 90 days in a period of six months. However, their civil rights are limited compared to the Estonian population and they can only vote in municipal elections.

'Indefinite citizens' can obtain Estonian citizenship if they have permanently resided in Estonia for five years and pass tests on the country's language, culture and history. Following the recommendations of the Human Rights Committee, the descendants of these persons who were born in Estonia after July 1, 1990 are entitled to a simplified process. Estonia does not recognize under any circumstances dual nationality.

The Republic of Latvia has a similar legal figure, "non-citizens", but its naturalization process is more restricted than Estonian.

Languages

The only official language in the Republic of Estonia is the Estonian language, which belongs to the Balto-Finnic branch of the Finno-Ugric language family. Estonian has many similarities with Finnish, incorporates loanwords from Germanic languages, and is one of the few languages in Europe without Indo-European origins. The traditional languages of southern Estonia, such as Võro or Seto, are officially defined as "regional forms of the Estonian language" and not as their own language. All other languages are considered "foreign languages" and are not protected. To obtain citizenship, as well as certain jobs in the public administration, it is necessary to demonstrate proficiency in Estonian in a state exam.

The official status of Estonian is recognized both in the Estonian Constitution and in the Language Law, which contemplates its status as the only lingua franca in public administration (national and local), in the judicial system and in security forces of the State. The public use of Estonian is regulated through a language policy protected by the Estonian Language Council. In the case of the Russophone minority, the Constitution provides that cities "with more than 50% of inhabitants belonging to a national minority" can use their language internally and in response communication, but any public communication in a foreign language must be translated into Estonian.

Estonia's education system is generally taught in Estonian, but there are schools geared towards the Russian-speaking minority where Russian is the vehicular language in primary education and Estonian is the second language. to a language immersion model where 60% of classes are taught in Estonian and 40% are in Russian.

Religion

The majority of the Estonian population does not profess any organized religion. According to the 2011 census, 54.14% of Estonians do not identify with any religion and 16.55% have no declared faith; 28% are Christians and the remaining 1.3% follow other denominations. Furthermore, only 16% of the population claims to believe in God. The irreligious tendency is more pronounced in the population of Estonian origin than in that of Russian origin. Article 40 of the Estonian Constitution guarantees the separation of church and state, as well as freedom of worship, and there is no official religion.

Estonia was one of the last areas of Europe to be Christianised, following the Baltic Crusade campaign of the Catholic Church in the 18th century xii. During the Protestant Reformation the region assumed Lutheranism, which for a time was the predominant denomination: when Estonian independence occurred in 1918, more than 80% of Estonians identified with the Lutheran church. The Soviet occupation led to a disincentive and even persecution of organized religions, and the number of faithful has continued to fall after the restoration of independence. The current 28% of Christians is distributed as follows: 17% Orthodox (mostly Estonians of Russian), 9% Lutheran and 0.5% Catholic.

There are two minority neopagan movements of Estonian origin, focused on the cult of nature: the maausk and the taara.

According to the Dentsu Communication Institute Inc, Estonia is one of the least religious countries in the world, with 75.7% of the population declaring themselves irreligious. The 2005 Eurobarometer survey revealed that only 16% of Estonians profess a belief in a god, the lowest belief in any country studied. A 2009 Gallup poll found similar results, with only 16% of Estonians Estonians describing religion as "important" in their daily life, making Estonia the most irreligious of the surveyed nations.

New surveys on religiosity in the European Union conducted in 2012 by Eurobarometer revealed that Christianity is the most important religion in Estonia, accounting for 45% of Estonians. The Eastern Orthodox are the most important Christian group in Estonia, with 17% of Estonian citizens, while Protestants represent 6% and other Christians 22%. Non-believers/agnostics represent 22%, atheists 15% and the undeclared 15%.

The Pew Research Center most recently found that in 2015, 51% of Estonia's population declared themselves Christian, 45% religiously unaffiliated - a category that includes atheists, agnostics and those who describe their religion as "nothing in particular," while 2% belonged to other religions. Christians were split between 25% Eastern Orthodox, 20% Lutheran, 5% Other Christian, and 1 % Roman Catholic. While the religiously unaffiliated were split between 9% as atheists, 1% as agnostics, and 35% as nothing in particular.

Most populated municipalities

Culture

The only official language in Estonia is Estonian. However, around a quarter to a third of the Estonian population is Russian-speaking. The non-recognition of their Russian tradition generates constant cultural friction with the population of that ethnic group, which in turn affects relations with Russia.

Literature

Estonian folklore has survived, through oral transmission, centuries of foreign domination, encompassing songs, poetry about the passing of the seasons, peasant labor, family life, love and myths. Runic songs are the earliest transmitted, dating back to the I century BCE. C. The first writings in the Estonian language are catechisms; for the Catholic of Johannes Kievel the date 1517 has been assumed; a Lutheran one dates from 1535. After World War II, Estonian literature was divided in two for almost half a century. A number of important writers spent the war years in Estonia and fled in 1944 to Germany (Visnapuu) or Sweden, either directly or through Finland (Suits, Under, Gailit, Kangro, Mälk, Ristikivi). Many of those who remained and did not bow to Soviet ideology either died in Siberia (Talvik and Hugo Raudsepp) or suffered a combination of repression, publication ban and internal exile (Tuglas, Alver, Masing).

The first author of the 19th century, Kristjan Jaak Peterson (1801-1822), was a student at the University of Tartu /dorpat. Despite being considered the father of modern Estonian poetry, he never saw his poems printed in his lifetime, although three of his poems were printed in German in 1823. The poems were published 100 years after his death. One of the projects Peterson completed in his lifetime was the German translation of Kristfrid Ganander's Mythologia Fennica ('Mythology of Finland'), a dictionary of mythology, the Swedish original of which had been published in 1789. Ganander's dictionary translation had many readers in Estonia and abroad, becoming an important source of inspiration and national ideology of early Estonian literature. His influence extended even into the early XX century.

Franz Kafka's impact on Estonian literature would influence the works of Arvo Valton (1935), with the novel Rataste vahel (In Filming, 1966); Enn Vetemaa (1936) and Mati Unt (1943), author of Võlg (Guilt, 1964), published in Canada in 1966, Hüvasti, kollane kass (Goodbye, cat yellow, 1963) and the drama Phaeton, päikese poeg (Phaethon, son of the sun, 1968). Less important were Uno Laht (1924) and Ellen Niit (1928).

Modern Estonian literature began to develop in the early XIX century with the poetry of Kristjan Jaak Peterson. The national epic poem Kalevipoeg ('Son of Kalev'), which was written by Friedrich Reinhold Kreutzwald in the middle of that century inspired by the Finnish epic poem Kalevala, collects tales, legends and sung verses. Lyrics experienced a boom at this time with poets such as: Lydia Koidula who published in 1867 The Emajõgi Nightingale; Johannes Barbarus, author of The Man and the Sphinx.

In the early 20th century, Estonian writers adopt French and Scandinavian models. Multifaceted authors include: Juhan Liiv, who published Collected Works in 1904; August Kitzberg, who wrote the drama The God of the Stock Market (1915); August Jakobson, the drama Fight Without a Front Line (1947); Friedebert Tuglas, the stories Division of lands (1906).

In the early period of independence, the writer Anton Hansen Tammsaare wrote the work Truth and Justice in 1926 and Põrgupõhja's New Vanapagan in 1939. Other prominent novelists included Oskar Luts, with his novel In the Shadow of the Golden Leaves (1933) and Mait Metsanurk, the novel Red Wind (1928). In poetry, Juhan Sütiste stands out, writing Sea and Forest (1937); Karl E. Sööt, from The sickle of the moon (1937); Anna Haava, and Hers Hers I Sing an Estonian Song (1935); Jaan Kärner, with the book of poetry A man at the crossroads (1932).

During the Soviet period, we find the poets Mart Raud, from New Bridges (1945); Vaarandi, from The dreamer in his window (1959), and Uno Laht, from With you, Homeland! (1953). Also noteworthy during this period were authors such as Johannes Semper, with the poems The sun in the sewer (1930); Erni Krusten, with his novel Diary of a Young Gardener (1941); Aadu Hint, with the novel Windy Shore (1951); Egon Rannet, the drama The devil in the flock (1949); Ralf Parve (1919), the poems In the combat post (1950) and Juhan Smuul, the poetic images For the apple trees to blossom (1951); Hans Leberecht, from Koordi Lights (1948), national prize for novels; Rudolf Sirge, with a War Story On the Watch of the New Day (1947); Eduard Männik, with the novel The struggle drags on (1950).

In recent years, the poet Jaan Kross, who was regularly mentioned as a candidate for the Nobel Prize in literature, has stood out. Upon his return from the labor camps and internal exile in Russia between 1946 and 1954 as a political prisoner, Kross renewed the Estonian poetry. Kross began writing prose in the mid-1960s. Jaan Kaplinski has become the most central and most productive modernist author of Estonian poetry. He has written essays, plays and has translated. He has taught in Vancouver, Calgary, Ljubljana, Trieste, Taipei, Stockholm, Bologna, Cologne, London, and Edinburgh. He has been a writer in residence at Aberystwyth University in Wales.

Music

Estonian musical tradition was first recorded in the text Gesta Danorum, written by Saxo Grammaticus in the 18th century XII, which quoted some of Estonian folk songs. The traditional instruments of the country are the bagpipe (torupill in its Estonian variant), the violin and the zither (talharpa and kannel).

Songwriting in Estonian is related to the country's national awakening (Ärkamisaeg) and has been an important part of its history, including the Singing Revolution. In 1869 the first edition of the Estonian Estonian Music Festival (Laulupidu), considered the largest choral event in the world. It was promoted by Johann Voldemar Jannsen, author among others of the national anthem, and its greatest peculiarity is that only songs in the Estonian language can be performed. Estonian. Currently held every five years; the 2014 festival brought together more than 42,000 singers. Since 2008 it has been considered a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO.

Estonian professional composers include Rudolf Tobias, Miina Härma, Artur Kapp, Eduard Tubin, Heino Eller and Gustav Ernesaks. Some of the most internationally renowned musicians of the XX century have been Arvo Pärt, forerunner of sacred minimalism, and the baritone Georg Ots.

As far as popular music is concerned, Estonia was proclaimed the winner of the 2001 Eurovision Song Contest with the song "Everybody", performed by Tanel Padar and Dave Benton, so public television was able to organize the 2002 Festival in Tallinn. Other performers who have gained international fame are Kerli Kõiv and the band Vanilla Ninja.

Telecommunications

According to research carried out by the World Economic Forum on the use of information technology in 104 countries (Global Report on Information Technology 2004-2005: Use of Information and Communication Technology in the World,), Estonia is ranked 25th in terms of infotechnology usage index, being the best ranked country in Eastern Europe.

Mobile telephony

The territory of Estonia is fully covered by digital mobile phone networks. The mobile phone has become a new way of making payments. Several Estonian banks offer the possibility of making payments via mobile phone. It is possible to pay this way in more than 1,000 establishments: hotels, beauty salons, shops, taxis or food companies, distinguished by a blue and yellow sticker with the legend Maksa mobiiliga ('Pay with the mobile'), indicating that it is possible to make purchases in this way.

Vehicle parking can also be paid for using your cell phone, either by making a call or sending a text message. In order for the parking attendant to know that the mobile phone has been paid for, an indicative sticker must be placed on the windshield of the car or on the window on the right.

Internet

In August 2000, the Estonian government pioneered the world by transforming its executive cabinet meetings into paperless sessions, using a system of networked databases. It is also possible to access the description of the expenses made by the State via the Internet and in real time, and citizens can make their income statement through the Internet.

During the period 2002-2004 computer and internet access courses for adults were organized all over Estonia. Vaata maailma ('A look at the world') has been an unprecedented training project completely financed by the private sector, which has served to train 102,697 people, 10% of the population Estonian adult. Studies carried out after the end of the project have shown that more than 70% of the participants have continued to use the internet after finishing the course.

All schools in Estonia are connected to the internet. Since 2003, all schools in the country have been able to use the virtual space for communication between home and school «E-escuela» (E-kool), created by the Una mirada al fundación world. The objective of the E-school is the active participation of parents in the study process of their children, making information related to studies more accessible to both parents and schoolchildren, and facilitating the work of teachers and the administration of the center. school. For example, E-escuela allows you to keep track of students' grades, as well as their absences from the study center, access the content of the classes and homework, as well as the final evaluations of the teachers about the work of the students. In June 2005 there were 78 schools in Estonia connected to the E-school (13% of the schools in the country) and every month more schools join this idea.

Media

The first audiovisual production in Estonia was a 1908 informative film dedicated to Gustav V of Sweden's official visit to Tallinn, which was later followed by documentaries directed by Johannes Pääsuke (1910s) and Theodor Luts. Radio broadcasts began in December 1926, while television began in July 1955. The Estonian government opened the media to the private market after the restoration of independence in 1991.

The Estonian Constitution recognizes and protects freedom of the press, and there is currently a wide range of radio stations, television stations and four nationwide newspapers in the country: Postimees, Õhtuleht, Eesti Päevaleht and Äripäev. Most of the media are in Estonian, although there are also publications for Russian speakers. The country ranks fourteenth in the ranking on freedom of the press prepared by Reporters Without Borders.

Eesti Rahvusringhääling (ERR) is Estonia's public broadcaster, founded in 2007 to bring together the management of public radio (Eesti Raadio) and television (Eesti Televisioon). The country's main news agency is the Baltic News Service (BNS), with coverage in all three Baltic countries.

Gastronomy

Estonian gastronomy combines elements common to the Baltic region with influences from Germany, Russia and Scandinavia. The traditional diet is made up of rye bread, pork, potatoes, preserves and dairy products; the country's climate has forced its inhabitants to rely heavily on seasonal products. Some of its most characteristic dishes are marinated eel, mulgikapsad —pork accompanied with sauerkraut—, verivorst —blood sausage—, smoked trout and mulgi pudder —Potato and barley pudding. Estonia is also one of the Eastern European countries with the highest production of alcoholic beverages.

Holidays

The calendar of holidays is fixed each year, depending on the weekly distribution. The repertoire of common festivals for all of Estonia is as follows:

| Date | Name | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1 January | New Year | |

| 24 February | Independence Day | Commemoration of the 1918 Declaration of Independence. |

| March or April | Good Friday | Christian holiday. |

| March or April | Easter Monday | Christian holiday. |

| 1 May | Feast of Work | |

| 23 June | Victoria Day | National holiday. Commemoration of the battle of Võnnu in 1919. |

| 24 June | Fiesta de San Juan | |

| 20 August | National Day of Estonia | National holiday. Commemoration of the restoration of independence in 1991. |

| Third Saturday, October | Day of Cultural Identity | National holiday. Commemoration of the ugrofine culture. |

| 25 December | Christmas | Christian holiday. Commemoration of the birth of Jesus of Nazareth. |

| 26 December | Day of St. Stephen | Christian holiday. |

| 31 December | New Year's Eve |

Sports

The Estonian Ministry of Culture states that 13% of the population is part of a sports club and more than 40% exercise regularly. The most practiced team disciplines are football and basketball, although the country has never excelled internationally in any of them. The Meistriliiga —the highest division of national soccer— was held for the first time in 1921 and was resumed after independence, while the basketball league began to be played in 1925; currently Estonia and Latvia organize a joint Division of Honor.

Driver Ott Tänak has won the 2019 World Rally Championship, while Markko Märtin came third in the 2004 edition. The country has also celebrated international triumphs in athletics, rowing, wrestling and cycling. As for winter sports, the modality where they have achieved the most victories has been cross-country skiing thanks to Andrus Veerpalu and Kristina Šmigun-Vähi, both Olympic champions.

The Estonian National Soccer Team is controlled by the Estonian Football Association and attached to UEFA and FIFA. He is currently considered a low-middle level team in Europe, since he has never qualified for the Soccer World Cup or the European Championship. The Meistriliiga is the first division and the highest level championship in Estonia. It was founded in 1991 after independence, and the two teams with the most titles and the most fans in the country are Flora Tallinn and Levadia Tallinn, with 13 and 10 titles respectively.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Estonia became a wrestling powerhouse, producing renowned fighters such as Kristjan Palusalu, Johannes Kotkas, Voldemar Väli, Georg Lurich and Georg Hackenschmidt.

Estonia competes in the Olympic Games through the Estonian Olympic Committee, founded in 1919 and whose debut took place in Antwerp 1920. The country usually achieves better results in the summer editions; the first Estonian Olympic medalists were wrestler Martin Klein and rower Mart Kuusik in 1912, while the country was still part of the Russian Empire, while the first Olympic gold was won by weightlifter Alfred Neuland in 1920. Tallinn became a sub-host sailing at the 1980 Moscow Olympics.

Contenido relacionado

Kingdom of Iberia

Watershed

Maracay

Machu Picchu base

Wadati-Benioff zone

![El 5,6 % del territorio de Estonia está cubierto de pantanos.[43]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/30/Endla_Looduskaitseala.jpg/253px-Endla_Looduskaitseala.jpg)

![La mitad del país está cubierto por bosques.[44]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/17/Tarvasj%C3%B5gi.jpg/271px-Tarvasj%C3%B5gi.jpg)