Esperanto

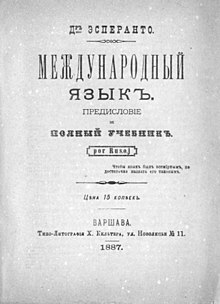

Esperanto (originally Lingvo Internacia, international language) is the most widespread and widely spoken international planned language in the world. The name comes from the pseudonym that L. L. Zamenhof, a Polish ophthalmologist, used to publish the basics of the language in 1887. Zamenhof's intention was to create a language that was easy to learn and neutral, more suitable for international communication. As stated in the Boulogne Declaration, the objective of Esperanto is not to replace national languages, but to be an international alternative that is quick to learn.

It is a language with a community of more than 100,000 - 2,000,000 speakers of all levels throughout the world, according to estimates from the end of the century combined with the most recent ones. Of these, about 1,000 are native speakers of Esperanto. In Poland, Esperanto is on the list of intangible cultural heritage. As a language, it enjoys some international recognition, for example two UNESCO resolutions o the support of personalities from public life.

Currently, Esperanto is a daily language that is used in travel, correspondence, social networks, chats, international meetings and cultural exchanges, business, projects, associations, congresses, scientific debates, in the creation of both original and translated, in theater and film, music, in print and online news, as well as radio and sometimes television.

Esperanto's vocabulary comes mainly from Western European languages, while its syntax and morphology show strong Slavic influences. Morphemes are invariable and the speaker can combine them in an almost unlimited way to create a great variety of words; For this reason, Esperanto has much in common with isolating languages, such as Chinese, while the internal structure of the words is reminiscent of binding languages such as Japanese, Swahili or Turkish.

The alphabet is phonetic. Complying then with the "one letter, one phoneme" rule, Esperanto is written with a modified version of the Latin alphabet, which, like most Latin alphabets, includes diacritics. In this case there are six: ĉ, ĝ, ĥ, ĵ, ŝ and ŭ; that is, c, g, h, j, s circumflex, and u short. The alphabet does not include the letters q, w, x, y, which only occur in foreign proper names (not assimilated).

Esperanto is an artificial language, with no native speakers in its origin, created explicitly in order to overcome the limits of communication between people around the world who speak different languages. The attempt to create a universal language that unites us has not yet achieved its goal, given the low percentage of speakers today, but if we take into account that it was born in 1887 and is now a community of more than 100,000 - 2 000,000 speakers of all levels spread all over the world, its growth was enormous.

Introduction

Esperanto is an international auxiliary language, a second language of communication after the native language of the speaker. The vocabulary comes mainly from Western European languages, while its syntax and morphology show Slavic influences and great similarities with isolating and agglutinative languages such as Chinese or Japanese, respectively. Esperanto grammar is summarized in 16 grammar rules and the alphabet is completely phonetic. Regular endings added to the stem allow you to systematically create words by combining roots, prefixes, and suffixes. For example, nouns are always formed with -o (suno, sol) and adjectives with -a (suna, sun). The agglutinating and isolating nature of Esperanto implies that starting from a very small number of morphemes (467 morphemes cover 95% of spoken Esperanto), all possible concepts can be expressed and vocabulary learning is accelerated. The frequent idiomatic expressions in natural languages and almost non-existent in Esperanto also accelerate their acquisition.

This type of characteristics of flexibility, simplicity and clarity are behind the propaedeutic value theory of Esperanto. For this reason, some polyglots and teachers who speak this language point to Esperanto as the best first second language to achieve better results in the following ones and use it in school programs or in their recommendations. Furthermore, mastering Esperanto does not imply knowing the ethnic culture of all their speakers, so Esperanto speakers clarify their own cultural details more frequently, instead of assuming such knowledge as often occurs in natural languages.

Due to the historical periods favorable to ideas of rapprochement of peoples, and thanks to its characteristics, Esperanto experienced a very high diffusion in its beginnings, becoming known as "the Latin of the workers". However, the times of world wars, totalitarian dictatorships and political repression slowed down its expansion. In April 1922, despite favorable reports from the League of Nations for incorporating Esperanto into the working languages, the French delegate Gabriel Hanotaux was the only one to veto Esperanto as a working language in the League of Nations, considering that it There was already a lingua franca: French. It is difficult to estimate the number of Esperanto speakers today because it is a second language and without a nation. Since the end of the last century, the most general estimate is two million speakers worldwide.

Esperanto has a presence on the Internet where a search for the word «esperanto» yields a result of more than 153 million pages. There are hundreds of specialized or general-themed organizations that use this language as a working language. The Universal Esperanto Association has thousands of members in 120 countries, official relations with the UN, UNESCO and the International Organization for Standardization, and organizes the Universala Kongreso (Universal Esperanto Congress) alternating continents annually.

History

Development

Esperanto was developed in the late 1870s and early 1880s by the Polish ophthalmologist Dr. Luis Lázaro Zamenhof. After ten years of work, Zamenhof spent translating literature into the language as well as writing original prose and verse, the first Esperanto grammar was published in Warsaw in July 1887. The number of speakers grew rapidly over the following decades, initially in the Russian Empire and Central and Eastern Europe, then in Western Europe, America, China and Japan. In the early years of the movement, Esperantists only maintained contact by correspondence, until the first Universal Esperanto Congress was held in the French city of Boulogne-sur-Mer in 1905. Since then, world congresses have been organized in the five continents year after year except during the two World Wars.

Initial Expansion

The number of speakers grew rapidly in the first decades, especially in Europe, then in America, China and Japan. Many of the first speakers migrated from another planned language, Volapük, which Zamenhof himself had learned.

In 1888, the journalist Leopold Einstein founded the first Esperanto group in Nuremberg (Germany); a year later, in 1889, the same journalist founded the first gazette in Esperanto: La Esperantisto. Authors such as Zamenhof, Antoni Grabowski, Solovjev, Devjatin or Leo Tolstoy published their writings there. After the collaboration of Tolstoy, who was one of the greatest defenders of Esperanto, the tsarist censorship decided to prohibit the entry of copies of the magazine into the Russian Empire.

At the end of the century, the Moresnet condominium established Esperanto as its official language, thus becoming the first country in the world to do so. This was mainly because he wanted to demonstrate the internationality and neutrality of the state. His song was called Amikejo (& # 34; place of friendship & # 34;). However, due to the German invasions in Belgium, Moresnet was dissolved in 1920, so since then there have been no countries with Esperanto as an official language.

The Esperanto movement grew steadily, attracting people from all social classes and all ideologies, although probably with a somewhat larger proportion of members of the advanced petty bourgeoisie. It soon took root in France, especially in the city of Céret and later in Spain, particularly in the city of Valencia.

In 1898, the former president of the First Spanish Republic, Francisco Pi y Margall, made Esperanto known in Madrid through a press article published in the republican newspaper El nuevo régime. After After the foundation of the first Esperanto circles, Esperanto courses and contact with similar groups in other countries, the Esperanto movement in Spain felt empowered to create the first state-wide group with the aim of spreading the international language. The Spanish Society for the Propaganda of Esperanto was founded in 1903. That same year the Valencian Esperanto Association was created.

Barcelona soon became an Esperanto center thanks to the work of the writer Frederic Pujulà, considered the introducer and greatest disseminator of Esperanto in Catalonia, who widely disseminated it through the modernist magazine Juventud, with collaborations in The Voice of Catalonia and with the publication of a large number of didactic works, such as grammars, courses and vocabularies.

In the early years of the movement, Esperantists only maintained contact through correspondence. In 1905, however, the First World Esperanto Congress took place in the French city of Boulogne-sur-Mer, with 688 participants from thirty countries and which consolidated the foundations of the Esperanto community. In this congress the Declaration of Boulogne was accepted, a basic constitutional document in which the causes and objectives of the Esperanto movement are defined and where the Fundamento de Esperanto was officially established as an essential and unalterable regulation of the language.. Since then, every year, except during periods of war, international congresses have been held on the five continents, apart from many other meetings and activities.

In 1908 a serious crisis arose within the Esperanto movement that threatened to destroy the language: the schism of the Ido. This schism was caused by a group of "reformist" Esperanto speakers, led by Louis Couturat, who presented a new language project considered by them to be a reformed Esperanto, and which in turn left the door open for new reforms. The pressure exerted by the idistas, however, led Zamenhof to propose several French-style reforms for Esperanto to the readers of La Esperantisto, such as eliminating diacritics, suppressing the accusative etc 60% of the magazine's subscribers rejected the reforms, as they understood that they would destroy the confidence of speakers in the stability of the language they had learned and started using. The idistas hindered the progress of Esperanto for two decades. Despite this, however, there was a notable advance of the Esperanto movement at the international level.

In 1909 the V Universal Congress of Esperanto was held in Barcelona, which led to the arrival in this city (and in the city of Valencia, where some activities were also carried out) of several thousand people from many countries, not only Europeans, and represented the main impetus to the Esperanto movement. During the celebration the International Catholic Esperanto Union was founded. Frederic Pujulà presided over the Congress and the Spanish King Alfonso XIII was the honorary president, who appointed Zamenhof Commander of the Order of Isabel la Católica. The same year, in Cheste (Hoya de Buñol), a resident of the town, Francisco Máñez, introduced Esperanto and managed to spread it. Cheste thus became one of the places in the world with the highest rates of population speaking or understanding Esperanto.

Esperanto in the political conflicts of the 20th century

Some regimes have persecuted and banned Esperanto during the 20th century for associating it with political activities. During the first third of the XX century, Esperanto was widely used and disseminated by the labor movement in Europe. In Germany it was known as the "Latin of the workers".

The X Universal Esperanto Congress, held in Paris in 1914, brought together almost 4,000 people. All this progress, however, came to an abrupt halt in 1914 with the start of the First World War. Another setback was the death of Zamenhof in 1917.

In 1922, the Third Assembly of the League of Nations accepted a report on Esperanto as an international auxiliary language, in which it is recognized as a "living language that is easy to learn". The French delegate Gabriel Hanotaux was the only one to veto Esperanto as a working language, considering it a threat to French, the international language of the time.

In the newborn Union of Soviet Socialist Republics there was a notable growth of Esperantism that was welcomed and promoted by the Soviet government, and in 1921 the Sennacieca Asocio Tutmonda (tr. approx. World National Association) was created, a A world labor organization of a socialist nature that established its base in Paris, opposed the nominal neutrality of mainstream Esperantism, which it described as "bourgeois", and proposed to use Esperanto as a revolutionary tool. However, Stalin reversed this policy in 1937. He accused Esperanto of being a "language of spies" and Esperanto speakers were shot in the Soviet Union.The ban on the use of Esperanto was in effect until the end of 1956.

In Spain, the movement of modern schools at the dawn of the XX century, to some extent culturally associated with anarcho-syndicalism Iberian, actively promoted the use of the language in its schools and cultural centers. Decades later, during the Spanish Civil War, the politicization of the Esperanto movement increased, being particularly linked to the anti-Franco resistance and the extreme left; used by anarcho-syndicalists, socialists, communists, Catalanists and also by a part of the Catholic right. With the International Brigades came some Esperanto-speakers from Eastern countries who established eventual contacts with Spaniards from the Republican zone. Parties and unions, such as the Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista (POUM), the PSUC or the National Labor Confederation, published bulletins and communiqués in Esperanto and offered courses at their premises. The Generalitat of Catalonia at the time used Esperanto extensively in its Propaganda Commission and in its press releases. In the Valencian region, the radio was also used as a means of propaganda. Two stations broadcast in Esperanto, one under the responsibility of the Socialist Party and the other of the Communist Party. The language also played an important role in the preparation of a massive prisoner escape that took place in the military prison of the Fort of S. Cristóbal (Navarra). In 1939, with the Francoist victory, the language was frowned upon by some authorities for having been promoted in previous decades as a political cause of Spanish far-left movements, but it was never officially banned and was tolerated. In the 1950s, earlier groups were reborn and new ones with greater political neutrality were founded. Esperanto acquired a new prestige in the face of a society tired of hatred and wars: if the Universal Esperanto Association throughout Europe had provided great services to prisoners of war on both sides, in the Spanish State the work of Esperantos in the shelter for children from families on both sides who suffered the consequences of the conflict.

The Second World War cut short the expansion of the Esperanto movement on a global scale once again. As a potential vehicle for international understanding, Esperanto aroused the suspicions of some totalitarian governments. The situation was especially harsh in Nazi Germany, the Japanese Empire, and the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin (as mentioned above). In Germany there was the additional motivation that Zamenhof was Jewish. In his book Mein Kampf, Hitler mentions Esperanto as a language that could be used for world domination by an international Jewish conspiracy. As a result of this animosity, Esperanto were persecuted during the Holocaust.

U.S. Senator Joseph McCarthy, known for his anti-communism, considered knowledge of Esperanto "almost synonymous" with sympathy for communism.

The United States Army decided to use it in a military training program during the 1950s and 1960s, at the height of the Cold War. The program, called The aggressor (in English, The aggressor ), consisted of forming two combatant sides, one would be the American and the other would be the enemy. In order to give realism to the maneuvers, the enemy side would use Esperanto to communicate verbally and in written documents, such as identifications. The army produced a field manual entitled "Esperanto, the language of the aggressor" (in English: Esperanto, the aggressor language) in which he described Esperanto as "a living and current international means of oral and written communication" which included a grammar of the language, vocabulary and phrases for everyday use.

International recognitions

Esperanto has no official status in any country, but it is part of elective curricula in many countries, especially China and Hungary. Numerous personalities such as former presidents of nations or organizations, ambassadors, mayors, councilors, etc. show their support for Esperanto during the celebrations of national or world congresses.

In the early 20th century there were plans to establish the first Esperanto state in the neutral territory of Moresnet, and in the In the short-lived artificial island-state of Isla de las Rosas, Esperanto was used as the official language in 1968. In China, during the Xinhai revolution of 1911, there were groups that considered making Esperanto the official language, but this move was rejected as untenable as proposed.

The Universal Esperanto Association has official relations with the United Nations Organization and UNESCO.

Relationship with other social movements

The creator of the foundations of Esperanto linked the language with a sense of solidarity among human beings across ethnic, linguistic and state barriers. Generally, this feeling is shared by a large part of the speakers, and is known by the expression internal ideo (internal idea), without this implying that it is a closed ideology. Zamenhof himself later created a more explicit doctrine that he called homaranismo ("humanity"), however, another current of Esperantists preferred a strict ideological neutrality. In the first Universal Congress of Esperanto this plurality was recognized, and the Esperantist was defined as one who uses the language, regardless of their motives.

Different social currents have used Esperanto as a means of expression, propaganda, or as a complement to their own ideals. There are associations that bring together members of the main religions, and also political and ideological currents. For much of its history, it highlighted the importance of the use of Esperanto by the socialist labor movement linked to proletarian internationalism, which created its own associations, and even its own ideology, sennacismo (anationalism). Non-socialist branches of the workers' and peasants' movement, as well as internationalist-conscious groups, also advocated Esperanto in the early 20th century, but perhaps with less intensity and less historical-ideological repercussion.

The language is also actively promoted, at least in Brazil, by followers of spiritualism. The Brazilian Spiritist Federation publishes courses and translations of basic books on Spiritism and encourages its followers to become Esperantists.

Esperanto today

Currently, Esperanto is a fully developed language, which evolves with its speakers under the recommendations of the Esperanto Academy and the basis of the Esperanto Foundation. Its community has thousands of speakers worldwide and a wealth of linguistic resources. Among the most internationally known Esperantophones are the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences Reinhard Selten, the world chess champion Zsuzsa Polgár and Tivadar Soros, father of financier George Soros.

The celebration of the 150th anniversary of the birth of Dr. Zamenhof (1859-1917), the initiator of Esperanto, began with a symposium at the UNESCO headquarters in December 2008, culminating in a Universal Esperanto Congress in his hometown of Białystok and ended with a symposium in New York attended by diplomats to the United Nations.

The Universal Esperanto Association (UEA) maintains official relations with UNESCO, the United Nations, UNICEF, the Council of Europe, the Organization of American States and the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). In 2009 she was presented to the Nobel Peace Prize, among others by the Polish Parliament. The Mongolian Esperanto Society has become the 70th national association of the UEA. National Esperanto associations function in around twenty African countries.

Many universities include Esperanto in their Linguistics courses and others offer it as a separate subject. Worthy of mention is the University of Poznan (Poland), with studies in Interlinguistics and Esperantology at the Adam Mickiewicz University.

The Bibliographic Yearbook of the North American Association of Modern Languages registers more than 300 scientific publications on Esperanto each year. The library of the International Esperanto Museum in Vienna (part of the Austrian National Library) has more than 35,000 copies in this language. Other large libraries, with more than 20,000 items each, include the Hodler Library at UAE headquarters in Rotterdam, the British Esperanto Association Library in Stoke-on-Trent, the German Esperanto Collection in Aalen, and the library of the Japanese Esperanto Institute in Tokyo.

With the popularization and expansion of new technologies, Esperanto has gained a new propelling force and thanks to this one can speak of a renaissance of the language. On the Internet you can access thousands of web pages in Esperanto, courses, forums, chat rooms, blogs, discussion groups, channels and videos, press, etc. As of September 2017, Duolingo, the popular website and application, has more than one million students of Esperanto in its English version and close to two hundred thousand in Spanish. In 2011 Muzaiko emerged, the first 24-hour radio station that broadcasts over the Internet. A significant piece of information on the situation of Esperanto is the number of articles in this language: Wikipedia, Wikipedia in Esperanto, has more than 242,000 articles in October 2017. In February 2012, Google Translator added Esperanto to its list of languages.

The language

Linguistic classification

As a constructed language, Esperanto is not genealogically related to the language of any ethnic group.

It could be described as «a language whose lexicon is eminently Latin and Germanic. From a morphological point of view, it is predominantly agglutinative, to the point of having a somewhat isolating character". Phonology, grammar, vocabulary and semantics are essentially based on Indo-European languages of Europe. The pragmatic aspects, among others, were not defined in the original Zamenhof documents.

Typologically speaking, Esperanto is a prepositional language and its most commonly used order by omission is subject verb object and «adjective - noun», although technically any order is possible, thanks to the morphemes that indicate the grammatical function of each word. New words can be created by using affixes and grouping of roots into a single word.

Spelling

The Esperanto alphabet is phonetic and is written with a modified version of the Latin alphabet. Like most Latin alphabets, diacritics are included, in this case 6: ĉ, ĝ, ĥ, ĵ, ŝ and ŭ (i.e. c, g, h, j, s circumflex, and short u). The alphabet does not include the letters q, w, x, y, except in non-assimilated foreign names. Therefore, this phonetic alphabet facilitates the use and rapid acquisition of both heard and written words, also by Asian speakers.

The 28 letters of the alphabet are:

a b c č d e f g ğ h k i j k k l m n o p r s zh t u ŭ v zAll letters are pronounced similar to their lowercase equivalents in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), with the exception of c and accented letters:

| Letra | Pronunciation |

|---|---|

| c | [ ] ] |

| č | [ ] ] |

| ğ | [ ] ] |

| [ x ] | |

| [ laughter ] | |

| . | [ laughter ] |

| ŭ | [ w ] |

There are two ASCII-compatible writing conventions currently in use but becoming rarer. These conventions substitute digraphs for accented letters. The h-system (“H convention”) (ch, gh, hh, jh, sh, u) is based on the digraphs “ch” and “sh” of the English, while the more common x (cx, gx, hx, jx, sx, ux) convention is useful for computer alphabetical ordering (cx comes after after cu, sx after sv, etc.).

Esperanto has been an easy language for Morse code communications since the 1920s. All Esperanto characters have Morse code equivalents.

Sample Sentences

Useful Esperanto words and phrases along with AFI transcriptions:

Vocabulary

Vocabulary has borrowings from many languages. Certain words, due to their international character, have their origin in non-Indo-European languages, such as Japanese. However, most of the vocabulary of Esperanto comes from the Romance languages (mainly Latin, Italian and French), German and English.

Criteria for the choice of vocabulary

The days of the week are borrowed from French (dimanĉo, lundo, mardo,...), many names of body parts from Latin and Greek (hepato, okulo, brako, koro, reindeer,...), the German time units (jaro, monato, tago,...), the names of animals and plants mainly in the names Latin scientists.

The meaning of many words can be inferred from their similarity to other languages:

- abdiki (“abdicate”), as in English, Latin, Italian and Spanish.

- abyss (“bachiller”), as in German and Russian.

- ablative (“ablative”), as in Latin, English, Italian and Spanish, but it is also recognized by Germans in grammar.

- funeral (“libra”), as in Polish, Russian, Yiddish and German.

- . (“cuerda”), as in German, Russian, Polish, Romanian and Czech.

In addition, Zamenhof carefully created a small base of root words and affixes with which to form an unlimited number of words. Thanks to this, it is possible to acquire a high communicative level having learned a relatively small number of words (between 500 and 1200 morphemes).

Phonology

Esperanto has five vowels and twenty-three consonants, two of which are semi-vowels. It has no tone. As in Nahuatl, the tonic stress always falls on the penultimate syllable, unless the final vowel o (or the a of the article) is elided, which commonly occurs in poetry or song. For example, familio («family») is [fa.mi.ˈli.o], but famili' is [fa.mi.ˈli].

Consonants

| Bilabial | Labio-dental | Alveolar | Post-alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Gloss | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ||||||||||||

| Occlusive | p | b | t | d | k | |||||||||

| Africada | ||||||||||||||

| Fridge | f | v | s | z | MIN | ♫ | x | h | ||||||

| Vibrante | r | |||||||||||||

| Approximately | l | j | ||||||||||||

Vowels

Esperanto uses the five vowels of Spanish, Latin or Swahili. No distinction is made in the length of the vowels and no differences are recognized between nasalized and oral vowels.

Previous Poster Closed i u Media e or Open a

There are six decreasing diphthongs: uj, oj, ej, aj, aŭ, eŭ ( /ui̯, oi̯, ei̯, ai̯, au̯, eu̯/).

With only five vowels, it tolerates a high degree of vowel variation that many other languages don't, and is helpful for beginners from a variety of backgrounds. For example, /e/ goes from the [e] (French é) to [ɛ] (French è). These differences almost always depend on the native language of the speaker. A glottal stop may optionally be used between adjacent vowels, especially if the vowels are the same, as in heroo (hero) and praavo (great-grandfather). Native speakers of languages whose phonotactics avoid hiatuses may prefer to use stop in such cases, thus avoiding pronouncing unwanted diphthongs.

Grammar

Words in Esperanto are formed or derived by combining roots and affixes. This process is quite regular, in such a way that words can be created while speaking, achieving the perfect understanding of the interlocutor. Compound words are formed in the order "modifier at the beginning, root at the end."

Different parts of speech are marked with their own suffixes: all common nouns end in -o, all adjectives end in -a, all adverbs derivatives end in -e and all verbs end in one of six verb tense and mood suffixes.

Plural nouns end in -oj, while direct objects end in -on. The plural direct object ends in -ojn. Adjectives are concordant to their noun; the respective endings are -aj for plural, -an, for direct object, and -ajn for direct object plural.

|

|

The six verb inflections are three tenses and three modes. Present tense -as, future tense -os, past tense -is, infinitive mood -i, mood jussive (imperative-subjunctive) -u, and conditional mood -us. There is no inflection indicating person or number. For example: kanti, to sing; my kantas, I sing; my kantis, I sang; mi kantos, I will sing; mi kantu, (that) sing; my kantus, I would sing.

|

|

Word order is comparatively free: adjectives can come before or after nouns, and subjects, verbs, and objects (marked with the -n suffix) can be placed in any order. However, the article, demonstratives, and prepositions always come before the noun. Similarly, the negative ne (not) and conjunctions such as kaj (and) and ke (that) must precede the phrase or clause. that they introduce In copulative clauses, word order is just as important as in Spanish: "un león es un animal" versus "un animal es un león."

The 16 rules of Esperanto

The 16 rules are a synthesis of the Esperanta gramatiko, which appeared in the Unua Libro (First Book) and are collected in the Fundamentals of Esperanto. This is by no means a complete grammar, although some enthusiastic Esperantists are inaccurate in their reporting. However, it is true that it illustrates in a simple and quick way the main characteristics of the language for connoisseurs of European grammatical terminology and such a level of synthesis may seem unthinkable in natural languages. The most complete grammar in Esperanto consists of 696 pages in format PDF and explains the language in detail for speakers of any language background.

Correlatives

In Esperanto, correlatives are a series of special words that express a simple idea (a lot, a little, some, that, this, all...) through words composed of two particles, so there are gestures to understand and memorize them. These particles combine to form a solid idea in the form of words in a completely regular way. This method of generating correlatives composed of particles is based, distantly, on the Russian language. The correlatives have their own grammar, since they have their own endings and rules, which are integrated in a totally regular way in the rules applicable to words with lexeme.

Fin Home | - Yeah. quality | - Yeah. cause | -Am time | - Hey. place | - the mode | - membership | - object | - quantity | - Wow. person |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| či- Everything. | čia every, all | . for all reasons | čiam always. | čie everywhere | čiel Anyway | čies of all | čio Everything. | čiom Everything. | čiu each, all |

| i- Some | ia Some | ial for any cause | iam ♪ | ie somewhere | iel somehow | I am. of someone | io Something. | iom something, a little. | iu Someone |

| ki- Question | Kia how (adjective) | kial Why? | kiam when | kie where | kiel how (adverb) | kies of whom | kio What? | kiom How much? | kiu who |

| Neni... Nothing. | nenia No. | nenial for no reason | neniam Never. | Baby. nowhere | neniel in no way | Nenies of nobody | Nenio Nothing. | Neniom Nothing. | neniu Nobody. |

| You... That's it. | Tia like that. | Tial That's why | tiam then. | tender There, there. | ♪ so. | ties of that | Uncle That's it. | tiom so much. | ♪ That's it. |

The correlative endings do not always agree with the stem endings. It is important to clarify that the correlatives that end with -u express people but are also used to express specific things (they express individuality). It is not the same to say “everything” (Ĉio) without being able to add nouns afterwards, than to say “everything” (Ĉiu) if you can add the noun (Ĉi u homo = every person). Those ending with -u are nouns when used alone, and adjectives when they accompany a noun. For example, in the sentence Ĉiuj diris... ("Everyone said..."), the word Ĉiu is used as a noun, but in Ĉiuj homoj diris... ("all the people said...") the same word is used as an adjective describing the word homo ("person"). Those ending with -o are always nouns. Those ending with -a are always common adjectives, while those ending with -es are possessive adjectives. Those ending with -am, -om, -el and -al are adverbs of time, quantity, manner and reason, respectively.

The correlatives that begin with k- can be used as interrogative words, but also as relatives, which are words that refer to what has already been said: «That is the house where I live” (You are the dome kie mi vivas). In the previous example, the word "where" is not used as an interrogative, but as an adverbial relative of "the house". The interrogative and relative correlatives work in the same way in Esperanto, as in Spanish. Relatives join two sentences into one, and that is why these sentences tend to have two or more conjugated verbs.

Esperanto uses two particles that modify correlatives: ĉi, which expresses closeness, and ajn, which expresses indifference. Both can be at the beginning or at the end of the correlative —or sometimes normal word— that they modify.

- Tie (here, there) → tender či (here)

- Tiam (at that time) → Či tiam (at this time)

- Tiu (that one, that one) → Či ♪ (here)

- Čio (all) → Či Čio (all this)

- iu (something) → iu ajn (anything)

- io (something) → ajn io (anything)

Braille

It is the version of Braille in Esperanto. The alphabet is based on the basic Braille alphabet, extending it for those letters with the circumflex accent.

Sign Language

Signuno is the Esperanto version of sign language.

Official language

Esperanto has not been a secondary official language of any recognized country, but it entered the educational system of several countries such as Hungary and China.

The Chinese government has used Esperanto since 2001 for daily news on china.org.cn. China also uses Esperanto on China Radio International and for the Internet magazine El Popola Ĉinio.

The United States Army has published military phrasebooks in Esperanto, which were used from the 1950s to the 1970s in war games by simulated enemy forces. A field reference manual, FM 30-101-1 of February 1962, contained the grammar, English-Esperanto-English dictionary, and common phrases.

Esperanto is the working language of several international non-profit organizations, such as Sennacieca Asocio Tutmonda, a left-wing cultural association that had 724 members in more than 85 countries in 2006. There is also Education@Internet, which has developed from an organization in Esperanto; most of the others are Esperanto-specific organizations. The largest of these, the Universal Esperanto Association, has an official consultative relationship with the United Nations and UNESCO, which recognized Esperanto as a medium for international understanding in 1954. The World Esperanto Association collaborated in 2017 with UNESCO to deliver an Esperanto translation of his magazine The UNESCO Courier (Unesko Kuriero, in Esperanto).

Esperanto is also the first language of teaching and administration of the San Marino International Academy of Sciences.[citation needed]

The League of Nations tried to promote the teaching of Esperanto in member countries, but the resolutions were rejected mainly by French delegates who did not believe it was necessary.

In the summer of 1924, the American Radio Relay League adopted Esperanto as its official international auxiliary language and hoped that the language would be used by radio amateurs in international communications, but its actual use for radio communications was negligible.

All personal documents sold by the World Service Authority, including the World Passport, are written in Esperanto, along with English, French, Spanish, Russian, Arabic and Chinese.

Although no State uses Esperanto as an official language, there have been several attempts throughout history:

- Moresnet Neutral (1908 - 1919)

- Republic of the Island of the Roses (1968 - 1969)

- Republic of Molossia

- Hutt River Principality

- Herzberg am Harz (since 2006).

Evolution of Esperanto

From 1887 until today, Esperanto has had a slow but continuous evolution and without presenting radical changes. These changes (sometimes barely noticed, sometimes bitterly disputed) encompass, apart from general vocabulary growth, the following trends:

- Preference for short formation of some words, such as spontana instead of spontanea.

- Enrichment in vocabulary nuances, for example in Blek (producing animal sounds) added a list of verbs for specific species.

- Evolution of semantic differences, e.g.: plağo: coastline to take bath and sun, often transformed by men for this goal; strando: more original, natural and «save» coastline.

- Use of k (in some cases h) instead of the oldest., mainly after r.

- Use of - Yeah. instead of -Uh! in country names, e.g.: Francio instead of Francujo (France).

- More frequent adverbialization, e.g.: Lastatempe instead of in the Tempo Lasta.

- Preference to avoid forming complex words.

Esperanto in education

A relatively few schools officially teach Esperanto in Bulgaria, China, and Hungary. Most Esperanto-speakers continue to learn the language self-taught, either through apps like Duolingo, learning portals like Lernu!, electronic or printed books, or by correspondence, adapted to email and taught by groups of volunteer teachers. Various educators estimate that Esperanto can be learned in anywhere from a quarter to a twentieth of the time required to learn other languages, depending on the level set and the languages of the speaker. Some argue, however, that this is applies only to native speakers of western languages.

Claude Piron, a psychologist at the University of Geneva and a United Nations Chinese-English-Russian-Spanish-French translator, claims that it is easier to think clearly in Esperanto than in many national languages (see Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis for more details on this theory) because "Esperanto relies exclusively on innate reflexes [and] differs from other languages in that you can always rely on the natural tendency to generalize patterns. [...] The same neuropsychological law —called by Jean Piaget generalizing assimilation— applies to both word formation and grammar».

Propaedeutic value of Esperanto

Several experiments show that studying Esperanto prior to studying another foreign language makes learning the other language faster and easier. This is probably because learning foreign languages becomes less difficult when you are already bilingual. In addition, the use of a grammatically simple and culturally flexible auxiliary language lessens the shock of learning a first foreign language. In one study, a group of European schoolchildren who studied Esperanto for one year and then French for another three years were shown to have significantly greater proficiency in French than a group who studied only French for four years. Similar results have been obtained when the second language was Japanese, or when the course was shortened to two years, of which six months were spent learning Esperanto.

Accreditation

The Universal Esperanto Association (UEA), in collaboration with the Center for Advanced Language Learning of Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE ITK for its acronym in Hungarian) in Budapest, has developed exams that They certify levels B1, B2 and C1, according to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages.

ELTE ITK is a member of the Association of European Language Examiners (ALTE) and was already conducting bilingual Hungarian-Esperanto exams before standardization to certify framework levels common European reference for languages, because in Hungary, Esperanto is included and is treated like any other foreign language in the university education system. The exams can be taken in any country and ELTE ITK delivers an accrediting diploma, although it warns that exams passed outside of Hungary will not have the same legal value within the state university.

This new monolingual exam system was presented at the end of 2008 and the exams have been held since 2009. Since 2009, large international meetings of Esperanto speakers have been used to organize exams, if there is a group of at least one of the three levels.

Criticism and modifications to Esperanto

Although the evolution that Esperanto has undergone since its publication has been relatively low, several reform projects have appeared, beginning with Zamenhof's proposals of 1894 (see reformed Esperanto). Zamenhof himself ended up rejecting these proposals when he verified by vote that the majority of the speaking community accepted the language as it was. He then left the evolution of this living language in the hands of the use of its speakers. So far, reform proposals, whether within the Esperanto framework or in the form of new Esperanto-based or non-Esperanto languages, have not been accepted by the speaking community for various reasons; although there is still controversy in certain sectors of the community, as to whether it is necessary to reform it or not, and even if it is possible in a language so widespread that it has long ceased to be a mere project with bases. The ido, proposed in 1907 by Louis Couturat, the representative to defend Esperanto, was the only initiative that achieved a significant number of followers. It meant a schism in the Esperanto community and a blow to the expansion of Esperanto, since the creation of two movements affected the expansion of both. Since the death of Louis Couturat, the main defender of the idist, he gradually lost idists, until a very small number of them remained.

Esperanto was conceived from the beginning as a language of international communication, more precisely as a second universal language. Since its publication, the debate has been constant as to whether humanity will be more and more capable of accepting this challenge and achieving the objective, and even if it would mean a positive advance for international communication, compared to the results of natural languages, in the economic, diplomatic, scientific, labor, etc.

Since Esperanto is a constructed language, it has met with much criticism regarding nuances and details that are ignored or underappreciated in ethnic languages used for international communication. The same arguments change with the passage of time or according to the language learned from the detractor. Some examples of the most common observations:

- Literary vocabulary is too extensive. Instead of deriving new words from existing roots, many authors adopt, especially for poetry, a lot of new roots in the language, closer to the lexicon of Western languages.

- Esperanto has not yet reached the expectations of its creator to become a second universal language spoken in mass. Although many Esperanto advocates give importance to the success achieved, according to the complicated 1999 estimates, the overwhelming proportion of the world's population and Esperanto speakers would be undeniable; of 1:3500 (a Esperanto speaker every three thousand five hundred people) as the most optimistic figure, and 1:43 000 as a more pessimistic figure, although with the emergence of the internet and the difficulty of censusing their speakers these estimates. It is also true that 96% of the world does not have English as a native language and it might seem unlikely — in addition to costly — for that 96%, to achieve a high level of English in 25% of the world before another change in the bridge language. The popular and innovative always begins as a minority. Like the French, the bridge ethnic languages are replaced by others.

- His vocabulary is based on international words and therefore on the great European languages that conquered the world, so in this aspect it would not be fully universal. A more universal vocabulary would be totally invented or would come from all or the great languages of the moment (subject to the change of time and loss of universality). Among others, Asian aspirants to learn Esperanto are slightly disadvantaged regarding native European languages with a certain strategic advantage. However, it is not surprising that Asians interviewed who learned both English and Esperanto prefer to learn the latter unanimously. The current solution to adopt ethnic languages and the need to memorize 467 morphomas to understand 95% of the Esperanto could detract from this criticism, not from other auxiliary languages but from international ethnic languages.

- Esperanto does not correspond to any native culture. The culture in Esperanto is that of its speakers that nurture it with its culture, in much western, Slavic and Asian. Although it has led to extensive international literature, the Esperanto does not therefore encapsulate a specific culture.

- It may be sexist that about 30 roots for humans are inherently masculine (e.g.: sinjor'o = sir) and their female equivalents are formed by adding a suffix (sinjor'in'o = ma'am), as happens in many unplanned languages (gallo gall'ina). However, those who stool sexist often ignore that "first" or "wife" are etymologically formed by the opposite process (kuzino kuzo) or that the word "malina" (other than woman, male) is common in the form of congresses. Note that the roots of the words of this language are mostly neutral (e.g.: tablo = table; vendist = seller/a; koko = gallinaceae) and the use of suffix in changes in frequency and context according to the speaker and his native influences. In addition, its use is much more frequent than that of the prefix masculinizer vir- or its adjective (vira = varonil). There are male roots and some ten is female (e.g.: damo = lady). This criticism, because of its more subjective character than objective, depends on the point of view of the speaker or detractor himself, since some people think that the Esperanto gives preference to the female sex, because it does not assign a suffix to the male (then the use of "malina"). Others believe that it gives preference to the neutral gender, since most of the roots refer to things, and in general, in the case of animals it is necessary to add a prefix to indicate the male gender. There is, however, an unofficial suffix for the male sex: -ičo. This suffix has not been officially accepted, nor do we find its particularly widespread use (the current majority use proposal would suppose that patro or sinjoro They will stop indicating sex suddenly, while all feminine roots would be preserved. Officially exists and used prefix Ge- to refer to the two genres, instead of using only the male, the neutral (whose plural does not necessarily imply the presence of the two sexes), or add the female, as is done, for example, in Spanish. Jorge Camacho Cordón, a Esperanto writer, has tried to address this problem, in the form of i.later derived in rhyme with an asexual pronoun other than the official ği for objects and, with less use, people without clear sex. Proposals for evolution and not reform are the use of new neutral roots of unrepresented languages that would leave the most frequent roots with sex inherent in oblivion.

- Esperanto can be artificial in written form. This subjective observation usually occurs in detractors who already know that they are reading a text in Esperanto and that it is a language not classified as "natural" in linguistics. The reasons are often based on the diacritic characters of the Esperanto that speakers without this type of sign or who learned or prefer English qualify as rare and tormentors. Also, for QWERTY keyboards, designed for English, you need to adjust or install a new keyboard only to write Esperanto, without using the available conventions. Since 2013 all phones with Android have the pre-installed Esperanto keyboard, with an international layout that includes hidden characters to write also in other languages with Latin alphabet. The characters that are criticized were specially invented for the language. It was not strange at the time when French, and not English, was the international language of the moment. The detractors criticize these characters adding an unnecessary degree of complexity to the language, such as ŭ, which replaces the English w. They also believe that any artificial language will be deficient by definition, although the Hungarian Academy of Sciences has declared that Esperanto meets all the requirements of a living language and it is known that the languages classified as natural are inventions of a human society, in a certain artificial way.

In the Esperanto-speaking community there is a difference of opinion regarding some criticisms; while some are accepted with healthy self-criticism and debates often arise about it, others are rejected outright, and in others the community simply does not find a real basis for their application. What almost everyone does agree on is that, although Esperanto is not a perfect language —if such a thing can exist—, it is from experience much better to play the role of auxiliary international language, benefiting everyone, than any other natural and even auxiliary language (without much development and with more quantitative than qualitative differences). In addition, Esperanto would correct the global economic imbalance that unfairly benefits countries that currently export native English, as shown in the Grin Report when asked "What would be the best choice of working languages in the Union? European?".

The Esperanto community

Geography and demography

Speakers of Esperanto are more numerous in Europe and East Asia than in the Americas, Africa and Oceania. They are more concentrated in urban than rural areas. Esperanto is particularly predominant in the countries of central, northern and eastern Europe; in China, Korea, Japan and Iran in Asia; in Brazil, Argentina and Cuba in America; and in Togo and Madagascar in Africa.

An estimate of the number of Esperanto speakers made by Sidney S. Culbert, an Esperantist and retired University of Washington professor of psychology who tracked and tested Esperanto speakers in sample areas in dozens of countries over a period of Twenty years ago, he found that between one and two million people spoke Esperanto at Level 3, "professionally competent" (able to communicate moderately complete ideas without hesitation and to follow speeches, radio broadcasts, etc.). Culbert's work consisted of a list of estimates for all languages with more than one million speakers. Culbert's methods are explained in detail in the letter to David Wolff Since Culbert never published detailed information regarding countries or regions, it is quite difficult to verify the veracity of his results.

Since then the figure of two million appears in Ethnologue, also referring to Culbert's study. If this estimate is correct and it has not increased, approximately 0.03% of the world's population would speak the language. This falls well short of Zamenhof's no-timeline target for it to become a universal language spoken on a larger scale, but it represents a level of popularity never achieved by any other language built, starting with a single speaker and without the means of national languages. Ethnologue also notes that there are between 200 and 2,000 native speakers of Esperanto (denaskuloj), who have learned the language by being born into a family whose parents speak Esperanto (this usually occurs in a family consisting of father and mother without a common language, who met thanks to Esperanto, or sometimes in a family of devout Esperantists). The latest census of the Hungarian government shows a sustained growth of natives in the country, above 800 individuals.

Marcus Sikosek has questioned the 1.6 million figure as an exaggeration. Sikosek estimates that even if Esperanto speakers were evenly distributed, it could be said that with one million speakers worldwide, in the German city of Cologne there would be at least 180 people with a high level of fluency. However, Sikosek finds only 30 such speakers in that city, and similarly found lower-than-expected numbers in places that are supposed to have a higher-than-average concentration of Esperanto. He also notes that there are a total of 20,000 members in various Esperanto associations (other estimates are higher). Although there are undoubtedly Esperanto speakers who are not members of any association, Sikosek considers it unlikely that there are fifteen times as many speakers as are registered with any organization. Others think that this ratio between members of the Esperanto movement and speakers of the language is not unlikely.

Finnish linguist Jouko Lindstedt, an expert on native Esperanto speakers, presented the following scheme showing the proportion of the Esperanto community's language skills:

- 1 000 are native Esperanto speakers.

- 10 000 speak fluently.

- 100 000 can use it actively.

- 1 000 000 understand passively a large percentage.

- 10,000 000 have studied it at some point.

According to an estimate carried out in 2016 by Svend Nielsen, there would be about 63,000 Esperanto speakers in the world, distributed as follows:

| Country | Esperanto speakers |

|---|---|

| Brazil | 7 314 |

| France | 6 906 |

| United States | 5 847 |

| Germany | 3 871 |

| Russia | 298 |

| Poland | 2 215 |

| Spain | 2 198 |

| Hungary | 1 997 |

| China | 1 626 |

| United Kingdom | 1 595 |

| Italy | 1 562 |

| Netherlands | 1 442 |

| Japan | 1 439 |

| Belgium | 1 237 |

| Mexico | 1 069 |

| Canada | 1 033 |

| Iran | 968 |

| Sweden | 910 |

| Czech Republic | 800 |

| Lithuania | 748 |

| Argentina | 738 |

| Australia | 737 |

| Switzerland | 724 |

| Ukraine | 694 |

| Colombia | 616 |

| South Korea | 585 |

| Finland | 582 |

| Denmark | 554 |

| Other | 10 687 |

The countries where Esperanto speakers are most common would be the following:

| Country | Esperanto speakers per million inhabitants |

|---|---|

| Andorra | 626 |

| Lithuania | 257 |

| Hungary | 204 |

| Iceland | 204 |

| Luxembourg | 194 |

| New Caledonia | 120 |

| Belgium | 108 |

| France | 106 |

| Finland | 105 |

| Denmark | 97 |

| Sweden | 95 |

| Switzerland | 86 |

| Netherlands | 84 |

| World | 8 |

Goals of the Esperanto Movement

Zamenhof's intent was to create an easy-to-learn language to foster equal understanding among peoples and to serve as an international auxiliary language: to create a second international language without replacing the original languages of the world's various ethnicities. This goal, widely shared among Esperanto speakers in the early decades of the movement, now competes with speakers who simply enjoy the language, culture, and community as something valuable and unique to be a part of.

Speakers of Esperanto who want Esperanto to be adopted officially and worldwide are called finvenkistoj, from fina venko, meaning "final victory". Those that focus on the intrinsic value of the language are commonly called raŭmistoj, after Rauma, Finland, where the short-term improbability of fine venko was declared and the value of Esperanto culture in the Youth Congress in 1980. However, these categories are not mutually exclusive (see Finvenkismo).

The Prague Manifesto (1996) presents the vision of a large part of the Esperanto movement and its main organization, the Universal Esperanto Association (UEA).

Culture

Esperanto Literature

Esperanto is the only constructed language that has its own sufficiently developed culture, and that has created an interesting literature made up of both translated and original works. The first book where the fundamentals of the language were offered already included a translation, and a small original poem. Later, the same initiator of the language, L. L. Zamenhof, continued to publish works, both translated and original, as a conscious way of testing and developing the potential of the language. Esperanto speakers today continue to regard Zamenhof's works as models of the best classical Esperanto. Other authors of the first stage were Antoni Grabowski and Kazimierz Bein (Kabe). Henri Vallienne is considered the author of the first novels.

It is estimated that the number of books published in Esperanto is over 30,000. The main book sales service, that of the Universal Esperanto Association, has more than 4,000 titles in its catalogue. In addition, each association National and many local clubs have their own bookstores and libraries. There are magazines dedicated exclusively to literature, such as Beletra Almanako and Literatura Foiro, while general magazines, such as Monato and La Ondo de Esperanto also publish fiction texts, original and translated.

In recent years, the so-called Iberian School has taken center stage among the authors of original books, a group that includes the writers Miguel Fernández, Miguel Gutiérrez Adúriz, Jorge Camacho, Gonçalo Neves or Abel Montagut.

Libraries are available to Esperanto speakers and sometimes the general public in some of the Esperanto associations. Two of the most important are: the Butler Library of the British Esperanto Association, which in 2011 housed around 13,000 volumes, the Hector Hodler Library in Rotterdam, which in 2007 had approximately 20,000 books.

Music in Esperanto

- Along with literature, music is one of the most developed components of Esperanto culture. Music of all kinds can be found on the market, from opera as Rusalka, from Dvořák, passing through folk, to rock, hip-hop, punk, noisecore, hardcore, electronics, etc. in Esperanto.

- The main producer of music records in Esperanto is Vinilkosmo, directed by Floréal Martorell, and based in Toulouse.

- A song by the soundtrack of Final Fantasy XI, called “Memoro de la Štono” (“Memory of the Stone”) has its lyrics in Esperanto.

- There is a Kore group song (Cordially) tribute to Freddie Mercury called My brilu plu, which is a version of the Queen group's The Show Must Go On.

Esperanto radios

There are several radio stations that broadcast in Esperanto:

- Muzaiko: is a radio station that transmits fully in Esperanto 24 hours a day online

- Vatican Radio: collection of official broadcasts in Esperanto of Vatican Radio

- International Radio of China: State radio from China, which includes Esperanto among the languages of its international version.

- Radio Habana: broadcast some programs in Esperanto, now uploaded to the Internet, and can be heard in America

- Esperanta Retradio: programs recorded on all kinds of topics, and transcribed

- Pola Retradio: Polish radio in Esperanto, which has been broadcast for more than 50 years, with recorded programs that usually include some related news on the one hand with Poland and on the other with the Esperanto movement

- Radio Verda: Although it is no longer active, around 200 programs can be heard on various topics: news, curiosities, readings, etc.

- Warsaw: record on the Esperanto movement

- Kern Punkto: about science, culture and society. Abonable to receive new mail programs

- Movada Vidpunkto:

- Radio Scienca

- Kern.punkto Info

- The Esperanto Wave

- 3ZZZ

- The bona renkontiğo

- Radio Frei

- Radio Aktiva

Esperanto TV

there are very few television experiments in Esperanto

- Internacia Televido (ITV, in Spanish International Television) was a television channel through the internet broadcast in Esperanto function between 2003 and 2006

- Other similar experiences are Bildo-Televido, Kataluna InformServo Televida or Farbskatol'

- Białystok's television in Poland has a Esperanto channel, created on the occasion of the World Esperanto Congress held in that city in 2009.

Esperanto and cinema

Cinema in Esperanto has had a minor development, mainly due to the difficulties of distribution in such a dispersed community. However, Esperanto has been used on occasions, especially in cases where a special effect was wanted, or when the plot involved people related to the language. Some examples:

- In the movie The Great Dictator Charles Chaplin, the posters, posters and other ghetto decorations were not written in German, but in Esperanto.

- The film Incubus from 1966, starring William Shatner, is the only American film shot entirely in Esperanto.

- In Street Fighter: The Last Battle from 1994 you can also see posters with words in Esperanto, in Latin character typography that wants to remind Thai. You can also hear one of the characters give orders to shoot in Esperanto.

- In Blade: Trinitythe action takes place in a bilingual city, where all the English and Esperanto posters are observed; we even attend a conversation in that language between one of the protagonists and a kiosk.

- In the Spanish film The pedal car, the protagonist, Álex Angulo, interprets a Esperanto professor who frequently greets and expresses himself in that language; in a scene you can hear to dictate a story to his students in this language.

- The recent appearance of the film Gerda Malaperis, based on a homonymous novel written in Esperanto, as well as many other films and documentaries completely in this language or at least it is used in specific dialogues.

- In Gattacathe loudspeakers of the Center where the main action runs emit advertisements in Esperanto.

- In the series Red dwarfSome of the ship's signs are in Esperanto.

- In a fantastic scene of the movie Captain, the protagonist's daughters speak perfectly in Esperanto.

- There are animated shorts in Esperanto and shorts in Esperanto contests organized by the International Radio China.

Recently, an Esperanto company has been created in Brazil called Imagu Filmoj that makes movies in Esperanto. He has already recorded Gerda Malaperis and La Patro (based on a story from Japanese literature).

Dates

The main dates or events of celebration or remembrance of Esperanto are:

- 26 July: Esperanto Day (in Esperanto: Esperantogo or naskiğtago de Esperanto). The first publication of the Unua Bookthe first book to learn the language grammar

- 15 December: Zamenhof Dayalso occasionally called Book Day in Esperanto (Esperanta Librotago in that language. The birth of the Esperanto creator, L. L. Zamenhof

Symbols

- The green color as a prominent symbol of the tongue and forming part of the other symbolic elements of the language.

- The Esperanto flag (Esperanto-flago). Symbolically the green field of the flag symbolizes hope, while the white box symbolizes peace and the star represents the five continents through its 5 points

- Green StarVerda stelo). The five star tips symbolize the continents as they were traditionally counted (Europe, America, Africa, Asia and Oceania).

- Jubile symbol (jubilea symbol). The symbol was adopted by various Esperantoists who consider the Esperanto flag as a very nationalist symbol for an international language.

- I hope so.hope). It is the official anthem of the Esperantist movement and the "national hymn" of Esperantujo.

Esperanto

An Esperantista is a person who speaks or uses the international language Esperanto or who participates in Esperanto culture, or who supports or studies it in one way or another.

Esperantujo

Used by speakers of the auxiliary language for international communication Esperanto to refer to the Esperanto Community and activities related to the language.

Hopeful

It is the term used for a language derived from the Esperanto community and an artificial language for describing a language project based on or inspired by Esperanto.

Esperanto Wikipedia

Since 2001 there is an Esperanto edition on Wikipedia.

Native Esperanto Speakers

They are people who have this language as their mother tongue, that is, they have learned it as their first language or as one of their first languages in childhood.

Pasporta Servo

Pasporta Servo (passport service) is a worldwide network available to Esperanto speakers. It consists of a list with the addresses of people from different parts of the world who are willing to accept Esperanto guests.

Anationalism

Anationalism (sometimes translated as apatriotism, in the original sennaciismo in Esperanto) is an ideology developed especially within the Esperanto movement, which does not accept the existence of nations defined as such, and claims a radical cosmopolitanism.

Organizations

There are several Esperanto organizations in the world but the most important are the Universal Esperanto Association (in Esperanto, Universala Esperanto-Asocio, UEA) and its youth branch the World Organization of Esperanto Youth (in Esperanto, Tutmonda Esperantista Junulara Organizo, TEJO).

Conferences

Universal Esperanto Congress (in Esperanto: Universala Kongreso de Esperanto) Congresses have been organized every year since 1905, except during the world wars. The Universal Esperanto Association has been organizing these meetings.

The International Congress of Young Esperantoists or Internacia Junulara Kongreso (IJK) is the official annual congress of TEJO.

Politics

Esperanto has been placed in many proposed political situations. The most popular of them is Europa-Democracia-Esperanto which aims to establish Esperanto as the official language of the European Union. The Grin Report, published in 2005 by François Grin found that the use of English as a lingua franca within the European Union costs billions a year and significantly benefits English-speaking countries. The report considered a scenario in which Esperanto would be the lingua franca, and found that it would have many advantages, particularly both economically and ideologically.

Learning on the web

There are several websites and apps for learning the language. The most important ones are:

- Duolingo

- lernu!

- jubilo.ca

- Esperanto Course for Speakers in Wikilibros

Vocabulary and practice:

- Plena Ilustrita Vortaro de Esperanto. In the internet -

- Rakontoj by Esperantujo (Small stories in Esperanto to practice)

- Vortoj: Spanish Dictionary – Esperanto (PDF)

Religion

Bible Translations

The first translation of the Bible into Esperanto was a translation of the Tanakh or Old Testament by L. L. Zamenhof. The translation was reviewed and compared with translations from other languages by a group of British clergymen and scholars before it was published by the British and Foreign Bible Society in 1910. In 1926 it was published along with a translation of the New Testament in an edition commonly called London Biblio. In the 1960s, the Internacia Asocio de Bibliistoj kaj Orientalistoj tried to organize a new version of the ecumenical Bible in Esperanto. Since then, the Dutch pastor Gerrit Berveling has translated the deuterocanonical books, as well as new translations of the Gospels, some of the epistles of the New Testament and some books of the Tanakh or Old Testament. These have been edited in several separate notebooks, or serialized in Dia Regno, but the deuterocanonical books have appeared in later editions of the Londona Biblio.

Christianity

Two Christian Esperanto organizations were formed early in the history of Esperanto:

- 1910: the International Union of Catholic Esperantists, which continues to operate today, making it one of the longest-lived Esperanto associations. Two Popes, John Paul II and Benedict XVI, have regularly used the Esperanto in multilingual blessings urbi et orbi in Easter and Christmas every year, since Easter 1994. In addition, the Vatican radio broadcasts regularly in Esperanto. In 1991, during the World Youth Day, Pope John Paul II was the first to speak publicly in Esperanto, addressing all participants.

- 1911: The International League of Christian Esperantists.

Churches that use Esperanto include:

- The Quaker Esperanto Society.

- There are cases of Christian apologists and teachers who use Esperanto as a medium. Nigerian pastor Bayo Afolaranmi is the author of the book Spirita nutraoo (spiritual food).

Chick Publications, a publisher of evangelistic-themed tracts, has published a series of Jack T. Chick comics translated into Esperanto, including Jen via tuta vivo (Here's Your Whole Life).

Islamic

Iran's Ayatollah Khomeini urged Muslims to learn Esperanto and praised its use as a means of improving understanding between peoples of different religions. After suggesting that Esperanto replace English as the international lingua franca, it began to be used in Qom seminaries. An Esperanto translation of the Qur'an was published by the state soon after. In 1981, it became less popular when it became clear that followers of the Baha'i faith took an interest in it.

Baha'iism

Bahaism, better known as the Baha'i faith, is a monotheistic religion whose adherents follow the teachings of Bahá'u'lláh, its prophet and founder, who is the Manifestation of God for the present time. Baha'ism encourages the use of an auxiliary language, without endorsing any specifically, but sees great potential in Esperanto to assume this role. It is considered, meanwhile, that any language adopted may be modified and adapted through consensus with representation of all countries. Several volumes of Baha'i scriptures have been translated into Esperanto. Lidja Zamenhof, daughter of the founder of Esperanto, was a Baha'i.

Buddhism

The Budhana Ligo Esperantista (Buddhist Esperanto League) existed from 1925 to 1986 and was refounded in 2002 in the city of Fortaleza, Brazil, during the LXXXVII Universal Congress of Esperanto. Numerous sacred Buddhist texts have been translated into Esperanto.

Oomoto

Oomoto is a Japanese religion founded in 1892 by Nao Deguchi. It is usually included within the new Japanese religious movements, organized outside of Shinto. It is partly a universalist desire, with a tendency to unify religions. A prominent role in their strategy is the use of the international language Esperanto, which is still strongly supported by followers of this group today.

Spiritism

Esperanto is actively disseminated in Brazil by followers of spiritualism. This phenomenon originated through Francisco Valdomiro Lorenz, an emigrant of Czech origin who was a pioneer of both movements in this country. The Brazilian Spiritist Federation publishes Esperanto textbooks and translations of the basic works of Spiritism, and encourages Spiritists to become Esperantists.

Because of this, in Brazil many uninformed non-Esperantists have the impression that Esperanto is a "language of spiritists"; Contrary to this, it is worth noting the difference between the relatively high number of spiritists among Brazilian Esperantists (between a quarter and a third) and the insignificant reciprocal number of Brazilian spiritists who speak Esperanto (just over 1 percent). This phenomenon does not occur in other countries.

Raelian Movement

The Raelian movement, a ufological sect founded by the Frenchman Claude Vorilhon, tried to spread its doctrines among Esperantists, and in the early eighties it published the translation of three of its leader's books into Esperanto: La libro kiu diras la veron in 1981 (The book that tells the truth), La eksterteranoj forkondukis min sur sian planedon in 1981 (Aliens took me to their planet ) and Akcepti la eksterteranojn in 1983 (Accept Aliens). Propaganda was also distributed in this language, with little real success.

Text Examples

Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Universala Deklaracio de Homaj Rajtoj, in Esperanto)

Žiuj homoj these denaske liberaj kaj egalaj laŭ dig kaj rajtoj. Ili possessed racion kaj konsciencon, kaj devus konduti unu al alia en spirito de frateco.All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and in rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience, and they must behave fraternally with each other.

The ingenious hidalgo Don Quixote de la Mancha by Miguel de Cervantes (La inĝenia hidalgo don Quixote de la Mancha, in Esperanto)

In vilağo de La Mancha, kies nomon mi ne volas memori, antaŭ nelonge vivis hidalgo el tiuj kun lanco en rako, antikva Šildo, osta čevala calj rapida levrelo.In a place of the wick, whose name I do not want to remember, there is not much time that lived a hidalgo of the lances in shipyard, ancient adarga, skinny dew and galgo corridor.

Songs on the death of his father by Jorge Manrique (Elegio je la morto de lia patro, in Esperanto)

Niaj vivaj these fluojfiniğantaj en la maro morto-svene; tien rekte kaj sen bruoj Nobelaro. senrevene. Tien rages fluoj famej kun humilaj kaj kun mezaj to the faith; tender čiuj these samaj: the subul' kun taskoj niaj

kaj la reğo.Our lives are the riversthat they will give in the sea, that is death; There go the lordships rights to end and consume; there the flowing rivers, there the other mediums and more boys; and come, they are equal those who live by their hands

And the rich.

Contenido relacionado

L.L. Zamenhof

Royal Spanish Academy

Chamorro language