Esker

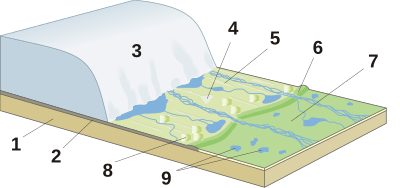

An esker is a long, narrow and sinuous ridge, composed mainly of sand and gravel, although at the end of its formation the esker is filled with sediments of all possible sizes, which makes the most homogeneous elongated mound. These ridges are deposited by rivers of meltwater that generally flow under a mass of glacial ice. As the transport capacity of water is much less than that of ice, when the glacier disappears the relief is inverted, with the old water river being the one that is highest, forming the esker itself, while the old shores of the same have been left. depressed due to the own weight and erosion of the ice that formed the old glacier.

Geology

Most eskers were formed inside ice-walled tunnels by streams that flowed into and under glaciers. They tended to form around the time of glacial maximum, when the glacier was slow. After the ice retaining walls melted, the stream deposits remained as long sinuous ridges. Water can flow uphill if it is under pressure in a closed pipe, like a natural tunnel in the ice.

Eskers can also form on top of glaciers by sediment accumulation in supraglacial channels, in crevasses, in linear zones between stagnant blocks, or in narrow inlets on the margins of glaciers. Eskers form near the terminal zone of glaciers, where the ice does not move as fast and is relatively thin.

Esker at Sims Corner Eskers and Kames National Natural Landmark, Washington, USA (Trees at the edge of the esker and the single lane road that crosses the esker on the right of the photo provide scale.)

Plastic flow and basal ice melt determine the size and shape of the subglacial tunnel. This, in turn, determines the shape, composition, and structure of an esker. Eskers can exist as a single channel or can be part of a branching system with tributary eskers. Often they are not found as continuous ridges, but have gaps separating the sinuous segments. The crests of the eskers' crests are usually not level for very long and are usually gnarled. Eskers can be broad-crested or sharp-crested with steep sides. They can reach hundreds of kilometers in length and are generally between 20 and 30 meters in height.

The trajectory of an esker is governed by the pressure of the water relative to the ice that covers it. In general, the ice pressure was at such a point that it would allow the eskers to run in the direction of glacial flow, but would force them toward the lowest possible points, such as valleys or riverbeds, that may deviate from the direct path of the river.. glacier. This process is what produces the wide eskers on which roads and highways can be built. Lower pressure, occurring in areas closer to the glacial maximum, can cause ice to melt above the flow of the stream, creating steep-walled tunnels with pronounced arches.

The concentration of debris rock in the ice and the rate at which sediment reaches the tunnel by melting and upstream transport determines the amount of sediment in an esker. The sediment generally consists of coarse-grained sand and gravel, deposited in water, although gravelly marl may be found where the rubble rock is rich in clay. This sediment is stratified and graded, and generally consists of cobble/cobble sized material with occasional boulders. Bedding can be patchy, but is almost always present, and cross-bedding is common.

There are several cases where inland dunes have developed alongside eskers after deglaciation. These dunes are often found on the leeward side of the eskers, if the esker is not oriented parallel to the prevailing winds. Examples of dunes developed into eskers can be found in both Swedish and Finnish Lapland.

Lakes can form within depressions in eskers. These lakes may lack surface inlets and outlets and have drastic fluctuations over time.

Examples of eskers

Europe

In Sweden, the Uppsalaåsen runs for 250 km and runs through the city of Uppsala. The Badelundaåsen esker runs over 300 km from Nyköping to Lake Siljan. The Pyynikki esker of Pispala in Tampere, Finland, lies on an esker between two glacially carved lakes. A similar place is Punkaharju, in the Finnish lakes.

The town of Kemnay, in Aberdeenshire, Scotland, has a 5km esker locally called the Kemb Hills. In Berwickshire, in south-east Scotland, is the Bedshiel Kaims, a 3 km long example that reaches 15 m in height and is the legacy of an ice stream in the valley of the River Tweed.

North America

The Great Esker Park stretches along the Back River in Weymouth, Massachusetts, and is home to the highest esker in North America (27m). There are over 1,000 eskers in the state of Michigan, mainly in the south central area of the Lower Peninsula. The longest esker in Michigan is the Mason esker, 35 km long, which runs south-southeast from DeWitt, through Lansing and Holt, before ending near Mason.

In the US state of Maine, cpn eskers can be up to 100 miles long.

The Thelon Esker is almost 800 km long and straddles the border between the Nunavut Territories and the Northwest Territories in Canada.

Uvayuq or Mount Pelly, in Ovayok Territorial Park, Kitikmeot Region, Nunavut, is an esker.

Sometimes roads are built along eskers to save costs. Examples are the Denali Highway in Alaska, the Trans-Taiga Highway in Quebec and the "Airline" of Maine State Route 9 between Bangor and Calais. In Adirondack State Park in upstate New York, there are numerous long eskers.

Etymology

In Spanish the term esker is sometimes used, directly brought from English. In turn, the term esker in English comes from the Irish word eiscir (Old Irish: escir), which means "ridge or elevation, especially that which separates two plains or depressed surfaces". and is used primarily to describe long sinuous ridges, now known to be deposits of fluvioglacial material. The best known example of this type of eiscir is the Eiscir Riada, which runs almost the entire width of Ireland from Dublin to Galway, a distance of 200 km, and still closely follows the main Dublin-Galway road.

The Swedish word ås, related, means "ridge".

Contenido relacionado

Aswan dam

Geology of the Falkland Islands

Popocatepetl