Ensanche District

The Ensanche (officially in Catalan Eixample) is the name given to the second district of the city of Barcelona, which occupies the central part of the city, in a wide area of 7.46 km² that was designed by Ildefonso Cerdá.

It is the most populous district in Barcelona in absolute terms (262,485 inhabitants) and the second in relative terms (35,586 inhabitants/km²).

The Ensanche district is where you can find some of Barcelona's best-known streets and squares, such as Paseo de Gracia, Rambla de Cataluña, Plaza de Cataluña, Avenida Diagonal, Aragón street, the Gran Vía de las Cortes Catalanas, Balmes street, the San Antonio roundabout, the San Pedro roundabout, the San Juan promenade, the Sagrada Familia square, the Gaudí square, and at its ends, the the Glorias Catalanas and the Francesc Macià square.

Furthermore, in the Ensanche there are numerous points of tourist and citizen interest such as the Basilica of the Sagrada Familia, Casa Milà, Casa Batlló, the National Theater of Catalonia, the Barcelona Auditorium, the Monumental bullring, the Casa de les Punxes, as well as numerous cinemas, theaters, restaurants, hotels and other places of leisure, such as parks.

Neighborhoods

- The Right of the Ensanche

- The Ancient Left of the Ensanche

- The New Left of the Ensanche

- Strong Pio

- Sagrada Familia

- San Antonio

During the first half of the 19th century, at the height of the Industrial Revolution, the cities that until then continued to have a medieval urbanism, many of them surrounded by walls, collapsed due to the installation of newly born industries and the demographic expansion.

The city of Barcelona, like many other European cities, is no stranger to this situation; but in his case, the walls themselves, the political situation and the fact that all the land outside the wall was considered a military zone, prevent new industries from being able to settle in its surroundings due to the prohibition to build in that large space flat, having exclusively agricultural use by the payeses (peasants) of Barcelona and nearby towns.

Demographic expansion and industries moved to areas that at the time were independent municipalities, today neighborhoods of the city, such as: Sants, Sarriá, Gracia, San Andrés or San Martín. The need to communicate with these populations gives rise to a series of roads that today continue to form part of the urban fabric. Among them, the current Paseo de Gracia is clearly recognizable, which connects Barcelona with Gracia and which during that time constituted not only a means of communication, but also a true meeting place, walk and recreation, creating gardens and areas on the sides of the road. used by the inhabitants of Barcelona as well as by those of Gracia, coming to exist a regular line of passenger transport in horse carriages, precursor of the current bus lines.

The exponential increase of the population in the intramural space was a health risk. The density reduced the urban space without air circulation, due to the fact that the surfaces of the properties were increasing.

The pressing need for expansion and the existence of a short period of progressive government, between 1854 and 1856, gave rise to the demolition of the walls, thus leaving open the path that would lead to present-day Barcelona.

Expansion projects

In 1855 the Barcelona City Council, despite not having directly intervened in it, initially considered the expansion project designed by the road, canal and port engineer Ildefonso Cerdá. The plan defines a garden city with large open spaces, the buildings, with only three floors, are very distant from each other, separated by wide streets and there is no differentiation between social classes as all the streets are the same. This combination of circumstances caused the bourgeoisie of the time to consider his proposal as a waste of land, and there was a clear conflict of interest between the parties. The protests of this bourgeoisie and its undoubted political influence make the city council backtrack and reject the initially approved plan.

Given the real need to develop a project that would allow the expansion of the city, in 1859 the city council called for a competition for urban projects in which the project by the architect Rovira i Trias was the winner. The project is, naturally, more in line with the claims of the bourgeoisie than Cerdá's plan: the streets are only 12 m wide, the possibility of exceeding the heights proposed by Cerdá is being considered, there is a clear separation of social classes and the buildings have a higher density.

Following the approval of the Rovira i Trias project in 1860, the central government of Madrid imposed a few months later, by Royal Decree, the plan of Ildefonso Cerdá, beginning its execution almost immediately, not without the protests of the people of Barcelona. However, and perhaps as a result of strong pressure, Cerdá himself in 1863 slightly altered his plan to increase the buildable area.

Despite the fact that for several decades there was resentment on the part of the Barcelona people and that the final result that we know today of the Ensanche de Barcelona has undergone many modifications to the one initially proposed by Cerdá, it is commonly accepted today that the plan imposed by decree was more rational and innovative than the competition-winning design, and has become an internationally recognizable and influential urban form.

The ideology of the Cerdá Plan

In “Statistical Monography of the Working Class”, Cerdá writes about his concern about the growth in the density of industries and the population. These studies lead him to carry out a comparative study with other important cities of the time, such as Boston, Turin, St. Petersburg and Buenos Aires, published in the Atlas of Theory where he seeks to study the methods used to apply them in his expansion project.

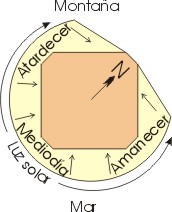

Cerdá proposes in his project an “unlimited widening”, developing the entire plain to its natural limits: Collserola to the north, the Besós river to the east, Montjuic to the west and the Mediterranean Sea to the south. He chooses for his project a hypodamic or checkerboard plan, which had already been used in colonial cities such as Filadelfia and Buenos Aires, being the most efficient option for the intense exploitation of the land, also granting an equitable value to the space.

He also understands that there are two fundamental behaviors in the life of the human being, moving and resting. The new city is based on two elements, those that favor movement, which are the roads, and the spaces designed for quiet and rest, the inter-roads.

The intersections became over time the strongest image of Barcelona. The 45° chamfers respond to the need to respond, not only to conditions of greater visibility and lighting, but also to different traffic situations, both vehicular and pedestrian.

The generous proportion between the amount of built-up land comes from the rules of the 1859 contest that establish that the built-up space be the same as that used for gardens. In the original plans, Cerdá designed the buildings around the perimeter of the block, freeing up the interior of the block. Said interior space should be used as a garden to favor ventilation and allow a greater degree of lighting. In this way, the Eixample buildings have a main façade facing the street and another facing the lungs of the block.

Geometry of the Ensanche

The large extension of land that corresponds to the Ensanche de Cerdá, from Montjuic to the Besós river and from the limits of the medieval city to the old neighboring towns, is conceived as a regular grid formed by the longitudinal axes of its streets, separated from each other by a distance of 133.3 m, the regularity of this grid is undisturbed along the entire urban layout and is justified, once again, in terms of equality, not only between social classes, but also in the comfort of the transit of people and vehicles, since in this way, whether traveling on a road or on its crossroads, the crossings between them are at the same distance, and since there are no roads that are more comfortable than others Home values will tend to equalize.

As far as orientation is concerned, some of the tracks run parallel to the sea, and the others perpendicular. This means that the orientation of the vertices of the squares coincide with the cardinal points and therefore all their sides have direct sunlight throughout the day, denoting once again the importance that the designer attaches to the solar phenomenon.

The streets generally have a width of 20 m, of which currently the central 10 m are intended for roads and 5 m on each side for sidewalks, however, and due to various needs, he designed some wider roads, without disturbing the regular grid of 133.3 m, but to achieve this, it adequately reduced the dimensions of the blocks affected by the widening of the tracks, so we can talk about the Gran Vía de las Cortes Catalanas under which the metro runs and the train, Calle de Aragón through which the railway passed for many years in the open air until it was finally buried, Calle Urgel and others.

Special mention should be made of the design of Paseo de Gracia and Rambla de Cataluña, where in order to respect the old Camino de Gracia and the natural slope of the waters, hence the name of Rambla, only two consecutive routes of special width where, in reality, based on the grid of 133.3 m, there should be three lanes. In addition, Paseo de Gracia, due to respecting the old layout, is not exactly parallel to the rest of the streets, which means that the existing blocks between the two mentioned roads, although they are square and with chamfers, present irregularities that give them the shape of trapezoids..

To all this we must add the presence of some special streets that do not follow the reticular layout but cross it diagonally, such as Diagonal avenue itself, Meridiana avenue, Pedro IV street, and others that were traced respecting the existence of old communication routes with neighboring towns.

Geometry of apples

The dimensions of the blocks are given by the aforementioned distances between the longitudinal axes of the streets and the width of these roads, so that when establishing a standard width of the roads at 20 m, the blocks are made up of quadrilaterals of 113.3 m, their vertices truncated in the form of a chamfer of 15 m, which gives a block area of 1.24 ha, contrary to the popular belief that blocks have an area of exactly 1 hectare.

Cerdà justified the chamfer of the vertices of the blocks from the point of view of the visibility that this gives to road traffic and in a vision of the future in which he was only wrong in the term used to define the vehicle, spoke of the particular locomotives that one day would run through the streets and the need to create a larger space at each intersection to favor the stop of these locomotives.

Within the space of each block, Cerdá conceived two basic shapes to situate the buildings, one presented two parallel blocks located on opposite sides, leaving a large rectangular space inside for a garden and the other presented two blocks joined in "L" shaped located on two contiguous sides of the block, leaving a large square space on the rest, also used as a garden.

The succession of blocks of the first type resulted in a large longitudinal garden that crossed the streets and the grouping of 4 blocks of the second type, conveniently arranged, formed a large built-up square crossed by two perpendicular streets and with its four linked gardens in one.

Evolution of apples

In this state of the project, and taking into account the difficulties it had in terms of the opposition to it by the people of Barcelona, it didn't take long for speculative activities and arguments to appear that tried to get more built space, the first of theirs was that if the streets were 20 m wide, the width of the buildings could well be increased to that same distance, the central zone of the blocks was later occupied with lower buildings, destined in most cases to workshops and small family industries, thus disappearing most of the central gardens, so that as a last resort to increase the built land, the two lateral ones already built were joined with buildings that joined them, completely closing the blocks.

It seemed that the speculative process was going to end here, but a new argument was added to it. If the streets were 20 m wide, there would be no problem in the buildings having a height of 20 m instead of the projected 16 m, since even with this height, with the sun at 45º, it would illuminate any building in its entirety without that no neighboring building would shade it, this argument together with the construction of lower ceilings resulted in gaining two stories in height.

Finally, taking into account a part of the previous theory. If one more floor is built on top of the current building, but with the façade removed towards the interior of the building as much as the height of this floor, it would be possible to increase the built space without the shadow of the building affecting the neighboring buildings when the sun is at 45ª, thus creating the attic floor and by the same theory the upper attic was built, withdrawing the façade as much to the rear.

The current Ensanche

Despite everything or thanks to it, since Cerdá conceived a utopian city, the current Ensanche is fully valid, after 150 years. At the beginning of the 21st century, the Eixample continues to be the heart of Barcelona today, and its construction continues, since although the central part represented by the district of the same name presents the typical physiognomy of the initial design, evolution remained stagnant for many years. from the Cerdà grid towards the Besós river, the district of San Martín de Provensals, whose lands were part of the expansion project, was occupied by industries that due to their characteristics could not be located in the central part, the need for spaces larger than the of a block prevented opening many of the streets projected like this for decades.

The changes in this city from the Cerdà Plan, not only produced changes in the physical space of the city, but also modified its morphology, facades, and society itself. The urban form that it adopted allowed for different urban functions, and also to adapt to new programs of use and forms in architecture according to the superblocks of the district of the expansion.

The last major push for the expansion occurred in 1986, when Barcelona was named the venue for the 1992 Olympic Games, and the Vila Olímpica del Poblenou was built respecting the layout of the expansion. This allowed the Ensanche and Avenida Diagonal to reach the sea after more than a century. The large industries moved out of Barcelona, leaving many of the factory chimneys as an ornamental testimony of the industrial activity in this area. All of this currently makes it possible to open roads and develop new areas, which in some cases are being built surrounded by landscaped areas, very similar to the original designs.

The Ensanche Derecho (from Balmes street to the right) is where the wealthiest people in this district are [citation required]. After Paseo San Juan, it drops in value again.[citation required] The four most expensive streets are:[citation required ] Paseo de Gracia (currently the second most expensive street in Europe[citation required]), Avenida Diagonal (Barcelona's most important street [citation required]), the Rambla de Cataluña and Balmes street. It must be emphasized that the streets near Paseo de Gracia have a very high price. Near this street live people from the haute bourgeoisie[citation required] (at least that was before) as well as people with very high purchasing power[ citation required] who likes to be close to the center and enjoy its privileges (good communications: subways, buses, train station...). In general, the northern part of Ensanche Derecho is the most valued[citation required] although it must be taken into account that Plaza de Cataluña is well known and, therefore, consequently, of high cost.[citation required] There are also areas for the upper-middle class[citation required] at the ends of the neighborhood (areas that are not so considered[citation required] although they also enjoy prestige[citation required]).

Contenido relacionado

Malt

Province of Santa Cruz de Tenerife

San Salvador