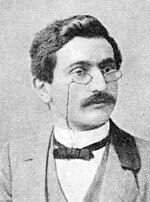

Emmanuel Lasker

Emanuel Lasker (Berlinchen, present-day Poland, December 24, 1868 - New York, January 11, 1941) was a German chess player, mathematician and philosopher, second world chess champion in 1894 to 1921.

He obtained the title at the age of 25 after defeating Wilhelm Steinitz and is the world chess champion who has held it the longest, 27 consecutive years, until in 1921 he lost the match in Havana against the great Cuban master José Raul Capablanca. He pioneered among his contemporaries in exploiting the psychological aspects of the game, skillfully taking advantage of the particular shortcomings of each of his opponents.

Biography

Youth and early career (1868-1893)

Emanuel Lasker was born on December 24, 1868 in Berlinchen (now Barlinek in Poland), a small German town near the Russo-Prussian border then belonging to Brandenburg. Coming from a humble Jewish family, his mother was named Rosalie Israelssohn and his father, Adolf Lasker, was a cantor in the local synagogue. At the age of twelve he had already given tests of talent for mathematics and was sent to a school in Berlin at care of his older brother Berthold, who taught him to play chess and took him to cafes where he soon began to earn money betting on his games.

After completing compulsory secondary school, he entered the Faculty of Mathematics at the University of Berlin in 1888 while continuing to progress in chess. He won a tournament at the Café Kaiserhof with 100% of the score and also a secondary tournament at the Sixth Congress of the German Chess Union, held in Breslau in 1889. This last triumph earned him the title of master and the possibility of being invited to international tournaments, making his debut in the one in Amsterdam in 1889 in which he was classified in second position, with 6 points from 8 games, behind Amos Burn and surpassing players of the stature of James Mason or Isidor Gunsberg. Already in this, his first important tournament, he carried out, in his game against Bauer, a combination based on the sacrifice of both bishops that would become a classic model.

On his return from Amsterdam, he defeated Curt von Bardeleben (+2 -1 =1) in a singles match and much more clearly Jacques Mieses (+5 =3). In 1890 he traveled to London, where he also defeated, among others, the English master Henry Bird. London was still renowned as the chess capital, so Lasker returned there to settle and in 1892 met Bird again, crushing him (+5 =0), as he did the illustrious Joseph Blackburne (+6 =4).

Conquest of the world championship (1894-1896)

Already thinking about the possibility of becoming world champion, he challenged one of the top contenders Siegbert Tarrasch, but he declined, answering that he had to win an important tournament first, and preferred to play a match with Mijail Chigorín who finished tied.

So, he decided to take a bold step: travel to the United States, where the champion, Wilhelm Steinitz, lived. There he played confrontations with various teachers, including against Jackson Showalter (+6 -2 =2), in addition to winning the New York tournament (1893) with 13 points out of 13 possible ahead of Albin, Showalter and a young Harry Nelson Pillsbury. Finally in August 1893 he challenged Steinitz and the champion accepted the challenge.

The match was held between March 15 and May 26, 1894 between New York, Philadelphia and Montreal and, although it was evenly matched at the beginning, Lasker's victory in a very complicated seventh game seemed to break the resistance of Steinitz, who at his advanced age had some health problems. The end result was a clear win for Lasker (+10 -5 =4).

The following year, in Hastings, the strongest tournament of the 19th century. The four main contenders for the title were present: Lasker, Steinitz, Tarrasch and Chigorín, but the victory corresponded to the new star, the American Pillsbury. Although Lasker defeated him in his own match, he was ultimately only able to finish third behind Chigorín, one point behind Pillsbury.

The rematch with Pillsbury would come in the six-round home run match-tournament held shortly after in Saint Petersburg (1895/96). Pillsbury defeated Lasker in their first two meetings and seemed destined for victory and the right to claim the title, but in their fourth meeting Lasker defeated Pillsbury with the black pieces in a sensational game that he himself came to consider the best of his career.. Finally Lasker won the tournament and Pillsbury, perhaps ill, collapsed and could only finish third. Immediately afterwards Lasker also won the Nuremberg super-tournament (1896) ahead of Géza Maróczy, Pillsbury and Tarrasch.

Shortly after, he played in Moscow (1896/97) the first rematch match in history against Steinitz, who at sixty years old was no longer in his best shape and had accumulated health problems. Lasker revalidated the title with the result of + 10 -2 =5.

World Champion (1897-1920)

Once the title was confirmed, Lasker left the competition to continue his studies in philosophy and mathematics, returning triumphantly in 1899, when he won the London tournament overwhelmingly (with 23.5 of 27, ahead of Maróczy, Pillsbury and Janowski) and then in Paris (14.5 of 16, ahead of Pillsbury, Maróczy and Marshall).

In 1899, Janowski was the first to propose a challenge to Lasker for the title of champion that did not come to fruition due to Lasker's demands both in the format of the competition and in the prize pool. At that time there were no established regulations and it was the current champion who imposed his conditions; Lasker argued that these, mainly the economic ones, should be elevated and would dignify professional chess (Steinitz himself had died in dire circumstances), although this also gave the title holder the possibility of avoiding opponents that he considered dangerous at any given time.

In these years Lasker was more dedicated to his academic studies in philosophy and mathematics than to chess. Led by the German mathematician Max Noether, he presented his doctoral thesis in 1900, which was published in Philosophical Transactions, the journal of the Royal Society. Until 1907, he only played in the Cambridge Springs, Pennsylvania, tournament in 1904, in which he shared second place with Janowski, behind Marshall.

Finally it was Marshall who, in 1907, challenged Lasker for the title thanks to the fact that North American fans managed to raise the necessary money. Although Marshall was a brilliant player and defeated Janowski in 1905 (+8 -5 =4), that same year he was crushed by Tarrasch (+8 -1 =8) and was unable to offer the slightest resistance to the champion either, losing the match by a resounding +8 =7. After the Cambridge Springs tournament, Lasker stayed in the United States, where he published Lasker's Chess Magazine for four years, which finally had to close due to difficulties. financial in 1908, the year in which he returned to Germany.

In 1908 he finally put the title on the line against the rival who was unanimously considered the most dangerous contender, Siegbert Tarrasch. The championship match, which would take the first to win eight games, began on August 17 in Düsseldorf and continued from game five in Munich. Lasker prevailed by a clear +8 = 5 -3 against a Tarrasch who, at 46 years of age, had perhaps left behind the peak of his strength.

The following year Lasker shared first place in the St. Petersburg tournament with Akiba Rubinstein. Both led their immediate followers by 3.5 points, but Lasker lost to Rubinstein in a rook ending that is now classic and his rival became the main contender for the world title. However, Rubinstein did not get funding to organize the match in his best years and, in addition to the fact that Lasker used his champion power to avoid his most dangerous rivals, he later lost the opportunity due to the outbreak of the First World War, at the end of which José Raúl Capablanca had already made enormous progress.

In 1910, in Vienna and Berlin, he played another championship match with the Austrian player Carl Schlechter. Although Schlechter was a strong chess player, it came as a surprise that Lasker was on the verge of losing the title: after being defeated in the fifth game after wasting his advantage he could only equalize the score (+1 -1 =8) after winning, after huge complications, the tenth and last game (in which a variant of the Slavic defense was played, to which Schlechter himself gave its name). The match was unusually short since, initially planned for thirty games, was cut to ten due to financial problems and also its regulations, which were not fully made public at the time, have been widely discussed by chess historians since under normal conditions Schlechter could have played a draw in the tenth game. However, it was stipulated that the applicant had to achieve a two-point advantage to be proclaimed champion.

Later that same year he retained the title with much more ease against Janowski. The match was played in Berlin and Lasker did not give his opponent the slightest chance: he won eight games without losing a single loss (+8 = 3).

More dangerous would have been a match against Capablanca, who had just obtained a sensational victory in the San Sebastián tournament (1911), his first appearance in the world elite. Capablanca accepted the $10,000 prize pool that was demanded of him, but rejected the rest of the conditions: the winner would be the first to win six games, although once the limit of thirty was reached, the champion would only lose the title if he lost by a margin of not less than two points. This last rule, similar to the one used in the match with Schlechter, was the one that Capablanca considered most unfair.

Affirmed his title, he did not play important tournaments until 1914 and in the meantime he married Martha Cohen in 1911, coming from a wealthy Jewish family. The couple settled in Berlin.

Saint Petersburg (1914)

In the pre-war years the most important chess event was undoubtedly the 1914 St. Petersburg super-tournament. It had been decided that the winner, other than Lasker himself, would acquire the right to play a match for the title world. The tournament consisted of a first phase by league system between eleven players that would classify the top five to a double round final. The preliminary league was won by Capablanca with a point and a half advantage over Lasker, followed by Tarrasch, Alekhine and Marshall. However, in the final phase Lasker played in a sensational way, scoring 7 points in 8 games and leading Capablanca in the total score by half a point. The decisive game was that of the second round between the leaders, a Spanish opening with the change variation, in which Lasker achieved one of the most famous victories of his career.

During the war, chess activity declined and negotiations with Rubinstein and Capablanca for a possible world championship dispute were also postponed. In 1916 Lasker played a friendly match against Tarrasch in Berlin with the result of +5 =0 -1 and, already in 1918, a double round tournament against Rubinstein, Schlechter and Tarrasch which he won with 4.5 points out of 6.

The end of his career (1921-1941)

Match for the world championship with Capablanca (1921)

After the war Lasker was practically ruined and in 1920 he resumed negotiations with Capablanca for the organization of the World Cup. They met in The Hague where Lasker, who preferred to play in the Netherlands and the United States, had to accept that the match would be held the following year in Havana since Capablanca's Cuban supporters had gathered a not inconsiderable fund. of $20,000. For the first time, the best of 24 games was played, a rule that later became common.

Therefore, the match was played in the candidate's country and under a climate that caused major adaptation problems for Lasker, who at 52 years old, twenty more than his rival, was also not in good health. Although Lasker did not put him in trouble at any time, the game was more disputed than the final score of 9 to 5 in favor of Capablanca (+4 =10) seems to indicate, at which point Lasker left the match on the recommendation of his doctor.

Later trajectory

After losing the title, Lasker continued to play at a high level, successfully facing both the masters of his generation and young chess players loaded with new ideas. Thus he won the international tournament in Mährisch-Ostrau (1923) finishing undefeated with 10.5 points out of 13 ahead of Richard Réti and Ernst Grünfeld.

Even more important was his clear victory in the New York tournament (1924), played in a double round with the presence of almost the entire world chess elite. Lasker prevailed with 16 points out of 20, beating Capablanca by one and a half points and Alekhine by four. Months later he finished second behind Bogoljubov in the first international tournament in Moscow (1925) leading Capablanca by half a point.

After Moscow Lasker gave up chess and devoted those years to his academic pursuits and also to other hobbies such as bridge and go. However, both he and his wife Martha were Jewish and Hitler's rise to power caused them to leave Germany and lose their property, which left them in a very difficult economic situation.

He reappeared in 1934 to take part in the Zurich tournament where he started brilliantly by defeating Max Euwe (who would wrest the world championship title from Alekhine the following year) but ultimately could only qualify fifth. The Laskers had moved to England for a few months, but they received the invitation to move to the Soviet Union, in the middle of the Stalinist era, when chess was dominated by the all-powerful Nikolai Krylenko. There he achieved the last success of his long career by obtaining third place, undefeated and preceding Capablanca, in the second international tournament in Moscow (1935), whose winners were Mikhail Botvinnik and Salo Flohr.

In 1936 he also participated in Moscow, although with less success, ranking sixth with 8 points out of 18. His last major tournament was in Nottingham (1936) where he drew with Botvinnik and Capablanca and defeated the current champion, Max Euwe.

In 1937 the Laskers left the USSR, which perhaps had something to do with the progressive fall from grace of Krylenko (who would be executed the following year) and went to the United States. Emanuel Lasker died at the age of 72, on January 11, 1941 in New York.

Influence on chess history

Lasker, unlike many of his contemporaries, did not make great contributions in the field of opening theory, given his tremendous strength he was partly content with getting playable positions. Yet it gave its name to several systems, such as the Lasker defense of the queen's gambit and the plan against the Evans gambit that effectively nearly eradicated it from master practice, as well as a scheme against the Reti opening that is still in effect today. Another example would be his treatment of the exchange variation of the Spanish opening, traditionally considered draw-prone, as in his game against Capablanca in St. Petersburg. Fischer later incorporated the variation into his opening repertoire with a similar approach, particularly evident in his game against Unzicker at the Siegen Olympiad in 1970.

As for the late game, Lasker clearly had outstanding technique, though he may not retain the same fame for his achievements in this phase of the game as some of his contemporaries, especially Capablanca and Rubinstein. In any case, many of his endings are now classics, such as the rook ending that he beat Rubinstein himself in St. Petersburg. Lasker is also the author of a famous compound ending, rook and pawn against rook and pawn, which appears in most manuals because the maneuver is of considerable practical value.

Deutsches Wochenschach (1890)

Whites play and win

However, the main characteristic of his style has always been considered to be the «psychological» aspect. This was already emphasized by his contemporaries:

The essential thing, the new thing, that Lasker has led to the game of chess, is not all pure technique, is the psychological game [...] the essential thing for him is the struggle of nerves. He seeks, by the medium of the chess game, to attack the psychology of his adversary.Richard Réti. The great masters of the board.

As it is often said, in his games, he often opted for plays that were not necessarily the best, but rather those that made the game more difficult for the opponent he was facing, as if he were looking for a way to prevail using the points in each match weaknesses of each of its rivals. But the truth is that Lasker had an impressive combinative strength and a brilliant technique in the endings, enough weapons to defeat most of his contemporaries. When he faced high-level contenders, his technique was not exactly "psychological" but rather he sought high-risk complications, demanding enormous calculation skills from the opponent, and trying to break the stereotypes of general game strategy in force at his time.. In those cases, he tried to alter the balanced, solid and safe game that, in his days, was believed to be irrefutable. In a way, Lasker was decades ahead of the style of play of his time and perhaps one must look to these breaks for the reason that he was the best player in the world for many years.

Contributions in other fields

Math

Lasker was a more than outstanding mathematician. He graduated from Landsberg an der Warthe (today Gorzów Wielkopolski in Poland) and later continued his studies in philosophy and mathematics at the universities of Berlin, Göttingen and Heidelberg.

In 1895 he had already published two articles in the prestigious journal Nature, and finally in 1900 he received his doctorate at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg where under the supervision of Max Noether he presented his doctoral thesis, which was published in Philosophical Transactions, the journal of the Royal Society.

His main contributions focused on a field, then actively developing, of abstract algebra that was being systematized by the Göttingen group of the eminent German mathematician David Hilbert. His most important work was published in 1905 in the journal Mathematische Annalen , whose result was later generalized by Emmy Noether, today known as the Lasker-Noether theorem and is a fundamental part of the theory of ideals.

The work of the Göttingen mathematicians, especially that of David Hilbert himself, had applications in many fields, including Albert Einstein's theory of relativity, whose development Lasker followed with particular interest. Lasker and Einstein had met in Germany at the home of the writer Alexander Moszkowski and had a friendship that Einstein later recalled in the foreword to a posthumous biography of Lasker:

Emanuel Lasker is certainly one of the most interesting people I've known in recent years... I came to know it well thanks to many walks where we exchanged views on the most varied topics, a rather unilateral exchange in which I received more than I gave.Albert Einstein. Emanuel Lasker. The life of a chess master (1952)

Strategy Games

Lasker was also interested in various strategy games, prone to mathematical analysis. Thus he invented a board game called lasca (or Laskers , the term comes from his name) whose rules he published in 1911, and proposed variations on the nim rules. He was also an outstanding player of go and especially of bridge.

Posts

Lasker published a book entitled Kampf (Fight) in New York, edited in 1907 by the Lasker Publishing Company, and which would be translated into English under the title Struggle. In this publication, which was a commercial disaster, he delves into the concept of struggle, strategy and confrontation from a philosophical point of view.

| Predecessor: Wilhelm Steinitz | Champion of the world of chess 1894-1921 | Successor: José Raúl Capablanca |

Contenido relacionado

Alejandro Villanueva Stadium

Garry Kasparov

Soccer in Spain