Emiral and Caliphate art

Andalusi Emiral and Caliphal art includes artistic manifestations from the Muslim conquest of the Iberian Peninsula to the emergence of the first Taifa kingdoms, that is, from the 8th to the 10th centuries.

This type of art will take place especially in Córdoba, capital of the caliphate created by Abderramán III in 929, where the most representative buildings of Andalusian power are built, not only the great aljama mosque, but also a caliphal city on the outskirts from the urban nucleus: Medina Azahara, very luxurious and short-lived, as it was destroyed by the civil war shortly after it was built.

In the rest of the peninsula some examples survive, especially in the city of Toledo, where there is still an Islamic gate of the fortified urban area, the Old Gate of Bisagra or Gate of Alfonso VI, as well as the mosque of the Bab neighborhood al-Mardum, better known after its conversion into a church as the hermitage of Cristo de la Luz. The Rabida of Guardamar del Segura in Alicante or the Ciudad de Vascos in the province of Toledo remained in a state of archaeological remains.

The refined court of the caliphs multiplied the decorative arts, such as ivory, ceramic, glass, or metal objects and fabrics. The Zamora Boat, intended for the wife of al-Hakam II, or the Leyre chest are preserved in the National Archaeological Museum. In the Episcopal Palace of Córdoba there is an interesting zoomorphic fountain made of limestone, known as the Fuente del Elefante.

Historical background

The Andalusian territory became, after the conquest, one more part of the Umayyad Caliphate of Damascus as a dependent Emirate, although the distance that separated it from the headquarters of the caliphate allowed its governors to enjoy relative autonomy. In 755, the future Abd al-Rahman I, the only Umayyad survivor of the massacre perpetrated against this dynasty by the Abbasids, arrived in al-Andalus. A year later he proclaimed himself an independent emir. Despite this, he continued to recognize the religious authority of the new Abbasid caliph whose court had moved to Baghdad.

The definitive step was consummated with Abd al-Rahman III. This monarch averted internal and external problems, pacifying the rebellious peninsular territory and facing the threat of the recently established Fatimid Caliphate of Cairo. This allowed him to proclaim himself Caliph in 929, affirming his political and religious authority over the Abbasids and Fatimids. The Caliphate of Córdoba was one of the moments of greatest splendor and cultural brilliance, although its flowering was short-lived. The beginning of the end began to be glimpsed when Almanzor relegated Hixam II (976-1013) and seized power. Upon the death of Almanzor's son and successor, civil struggles broke out between factions to impose their own candidate, which determined the independence of the different territories and the abolition of the caliphate in the year 1031.

Architecture and urbanism

Córdoba

The Mosque of Cordoba

Artistic enterprises were centered from the outset around its capital Córdoba, which was endowed with a congregational mosque destined to become the most important monument in the Islamic West. The work was started by Abd al-Rahman I on the site of the Visigothic Basilica of San Vicente which, during the preceding period, had been shared by the two communities: Christian and Muslim. In 784 this monarch decided to build a new basilica-type mosque with eleven naves perpendicular to the qibla wall -following the model of the Al-Aqsa mosque in Jerusalem, one of the most important holy places in the Islamic world-. Its most unique feature solves, at the same time, technical and functional problems. It is about the organization of its arches with a double superimposed arch: a horseshoe arch that acts as a brace by bracing a more slender structure formed by a semicircular arch that supports, in turn, the wall that supports the roof. Both this system and the alternation of voussoirs, brick and stone, have precedents in the Los Milagros aqueduct in Mérida.

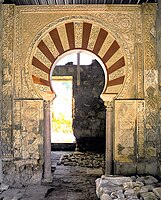

Successive enlargements, carried out until the X century, were motivated by the increase in population and the need to have a suitable place for worship. Thus, the works of Abd al-Rahman II, in 833, consisted of demolishing the qibla wall, extending the mosque to the south. Abd al-Rahman III acted in the opposite direction, expanding the courtyard to the north and erecting a new minaret that still remains, although hidden, inside the great bell tower of the XVI. The previous efforts culminated with the intervention of al-Hakam II, around 961, in which he once again expanded the prayer hall to the south, introducing different innovations. It establishes a "T" scheme, similar to that of the Great Mosque of Kairouan, enhanced by the use of domes whose ribs do not cross in the center, lobed arches, different types of interlocking and superimposed arches as well as by capitals and columns made ex profeso by the caliphal workshops. The lavish decoration of this extension, especially in the area of the mihrab and the maqsura, received great influences from Byzantine art when it introduced the mosaic technique, and constitutes the crowning work of Caliphate art.

In the last decades of the X century, Almanzor enlarged the entire eastern side of the great mosque, which came to include nineteen ships, although without introducing news of interest.

Medina Azahara

In the year 936, the self-proclaimed caliph Abd al-Rahman III, following the oriental tradition, according to which each monarch built his own palatine residence as a symbol of prestige, decided to found the courtly city of Medina Azahara (Hispanicization of the Arabic Madīnat al-Zahrā). For this purpose, a few kilometers from Córdoba, he chooses a gently sloping terrain on the slopes of the Sierra Morena, which allows him to organize the walled enclosure into three terraces. In them he arranged the palatine residences, reception rooms such as the so-called Salón Rico, baths, congregational mosque, mint, caliphal workshops, gardens and zoological park. These works were completed by al-Hakam II, although their splendor was short-lived, ending the city in the first revolts of 1010 that ended with the fall of the caliphate.

During the construction of Medina Azahara, the ataurique technique was especially developed for wall decoration in halls and rooms, as well as the so-called wasp nest capital as a symbol of Caliphate architecture.

Córdoba Arab Baths

According to classical sources, during the splendor period of the caliphate there were up to 4,000 public baths or "hammam" In cordoba. Despite the fact that this number is questioned by historians, there must have been many spaces for religious hygiene rituals. Of all of them, only four have survived to this day, some integrated into Christian constructions after the fall of the Caliphate. The caliphal baths, built in the X century during the period of Al-Hakam II, are the only vestige remaining today in day of the Alcázar Califal. Also of caliphal origin, and reused in Christian times, are the Arab Baths of La Pescadería and the Arab Baths of San Pedro (the latter with the peculiarity of being the only ones left that were built outside the medina). Finally, and very close to the Mosque of Córdoba, we find the Arab Baths of Santa María, although they have been much renovated today, having been converted into a tenement house during the following centuries.

Other manifestations

In Córdoba, there are also important vestiges of various neighborhood mosques, the first of which is the minaret of the church of San Juan de los Caballeros, which was reused as the bell tower of the aforementioned church after the Christian conquest of the city. It is the Caliphate minaret that has survived the most intact to this day, given the few modifications it underwent over the centuries. Another of the most important vestiges is the church of the convent of Santa Clara, where a significant number of remains can still be seen from the structure of the mosque on which it sits, such as the qibla wall, the ablutions patio, the minaret in a high degree of conservation and a blinded horseshoe arch that can be seen from Osio street. The churches of San Lorenzo and Santiago also preserve minarets converted into bell towers, built on top of old neighborhood mosques, where remains of twin horseshoe arches from the Caliphate period can still be seen.

Rest of the Iberian Peninsula

Of the artistic undertakings undertaken in the Emirate period, those carried out during the reign of Abderramán II stand out, whose court welcomed numerous artists, fashions and oriental customs. He promoted, among other constructions, the works of the citadel of Mérida and improved the walls of Córdoba and Seville.

In the rest of the peninsular territory, the artistic flourishing promoted by the caliphate is also evident. Proof of this is the city of Toledo, where remains of its fortification can still be seen, as well as some of the vestiges that define its citadel, medina, suburbs and surroundings, such as the Puerta Vieja de Bisagra or Puerta de Alfonso VI.

Among its constructions, the small mosque of Cristo de la Luz or Bab al-Mardum stands out. Its square plan, organized into nine domed sections, presents a plan and elevation that connects with the Tunisian model of the Aghlabid mosque of Bu Fatata.

Apart from the exceptional character of Toledo, works such as the Rábita of Guardamar del Segura (Alicante), the Castle of Gormaz (Soria) or the city of Vascos (Toledo) also occupy a prominent place.

Religiously, the Mosque of Almonaster la Real (Huelva) stands out, being this the only Andalusian mosque that has been preserved almost intact in Spain in a rural area. It was built during the Caliphate period, between the 9th and 10th centuries, with hauling material from a previous Visigothic basilica.

Other arts

Ivory

The refinement that reigned in the Caliphate court sponsored the creation of luxury manufactures that, under royal patronage, were translated into the most varied artistic expressions. The works in ivory stand out, in which objects for palatal use were made, such as boats and chests destined to store jewels, ointments and perfumes, among which the Zamora Boat (National Archaeological Museum) stands out, destined for the wife of Alhakén II, and the Leyre chest, (Museum of Navarra). Court scenes are usually inscribed in its profuse plot of vegetation at the same time as bands with epigraphic inscriptions indicate the addressee and even the master who executed the piece.

The pieces of this material that we know today are preserved thanks to the Christian appreciation that used them as reliquaries for their monasteries and cathedrals, or to store jewellery, ointments and perfumes. Basically they respond to the typology of boats and chests, the first being cylindrical in shape with a hemispherical lid, and the second in a rectangular prismatic shape, with a flat or truncated pyramidal lid. They are always small-format pieces, generally ranging between 11'5 and 7'5 cm.

Fabric

The monarchs, as in Baghdad and Cairo, organized their own weaving factory or tiraz whose foundation marks the beginning of the history of silk weaving production in Al-Andalus. Its vegetal and figurative motifs, geometrized, are inscribed in medallions forming bands as they appear in the veil or almaizar of Hixam II that, like a turban, covered his head hanging down to his arms.

Metal

There were also workshops that worked bronze whose figures represent lions and deer with the body covered with tangent circles that evoke fabrics and that possibly served as fountain spouts. Its formal and stylistic parallelism with Fatimid pieces has led to controversies about the affiliation of any of the pieces. Several specimens of fawn figures are preserved, such as the Medina Azahara Fawn, in the Archaeological Museum of Córdoba, and the Medina Azahara Doe, in the National Archaeological Museum,

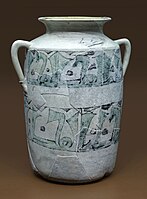

Ceramics

The ceramic has a type of production known as "green and manganese". Its decoration based on epigraphic and geometric motifs and a strong presence of figurative motifs is achieved by applying copper oxide (green) and manganese (IV) oxide (purple).

Contenido relacionado

Alessandro Volta

Russian painting

Spanish subgroup