Electronic music

Electronic music is that type of music that uses electronic musical instruments and electronic music technology for its production and performance. In general, one can distinguish between sound produced by using electromechanical means, of that produced by electronic technology, which can also be mixed. Some examples of devices that produce sound electro-mechanically are the telarmonium, the Hammond organ, and the electric guitar. The production of purely electronic sounds can be achieved by devices such as the theremin, the sound synthesizer or the computer.

Electronic music was originally and exclusively associated with a form of Western cultured music, but since the late 1960s, the availability of music technology at affordable prices led to music produced by electronic means becoming increasingly popular. popular. Currently, electronic music presents a great technical and compositional variety, ranging from forms of experimental art music to popular forms such as electronic dance music or EDM (for its acronym in English: Electronic Dance Music) or shuffle dance.

Origins: End of the 19th century and first decades of the 20th century

The ability to record sounds is often associated with the production of electronic music, although it is not absolutely necessary for it. The first known device capable of recording sound was the phonautograph, patented in 1857 by Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville. This instrument could record sounds visually, but not play them back. In 1878 Thomas A. Edison patented the phonograph, which used cylinders similar to Scott's apparatus. Although cylinders continued to be used for some time, Emile Berliner developed the disc phonograph in 1889. On the other hand, another significant invention that would later have great importance in electronic music was the audion valve, of the triode type, designed by Lee DeForest.. It is the first thermionic valve, invented in 1906, which would allow the generation and amplification of electrical signals, radio emission and electronic computing.

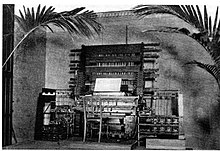

Before electronic music, there was a growing desire among composers to use emerging technologies in the field of music. A multitude of instruments were created that used electromechanical designs which paved the way for the appearance of electronic instruments. An electromechanical instrument called a telarmonium (sometimes Teleharmonium or Dynamophone) was developed by Thaddeus Cahill between 1898 and 1899. However, due to its immense size, it never it came to be used.

The theremin, invented by Professor Léon Theremin around 1919 and 1920, is often considered the first electronic instrument. Another early electronic instrument was the Ondas Martenot, invented by the French cellist Maurice Martenot, who became known at be used in the work Turangalila Symphony composed by Olivier Messiaen. This was also used by other composers, especially French, such as Andre Jolivet.

New aesthetics of music

In 1907, just one year after the invention of the triode-type audion valve, the Italian composer and musician Ferruccio Busoni published Outline for a New Aesthetics of Music, which dealt with the use of both electronic and other sources in the music of the future. He wrote of the future of microtonal scales in music, made possible by Cahill's teleharmonium: "Only by a long and careful series of experiments, and continual training of the ear, can this unknown material be made accessible and plastic for the coming generation and for art». As a consequence of this writing, as well as through his personal contact, Busoni had a profound effect on a multitude of musicians and composers, especially his disciple Edgard Varèse.

Futurism

In Italy, Futurism, a movement of artistic avant-garde currents founded by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, approached musical aesthetics as a transformation from a different angle. An idea of the futurist philosophy was to value noise, as well as to give artistic and expressive value to certain sounds that had not previously been considered musical.

Francesco Balilla Pratella's Technical Manifesto of Futurist Music, published in 1911, states that his credo is to "Present the musical soul of the masses, of the big factories, of trains, transatlantic cruise ships, battleships, automobiles, and airplanes. Add to the great central themes of the musical poem the mastery of the machine and the victorious reign of electricity".

On March 11, 1913, the futurist Luigi Russolo published his manifesto The Art of Noises (original in Italian, L'arte dei Rumori). In 1914 he organized the first concert of The Art of Noises in Milan. For this he used his Intonarumori, described by Russolo as "noisy acoustic instruments, whose sounds (howls, bellows, shuffling, gurgling, etc.) were manually activated and projected by means of winds and megaphones". Similar concerts were organized in Paris in June.

1919-1929

This decade brought a wealth of early electronic instruments, as well as early compositions for electronic instrumentation. The first instrument, the theremin, was created by Léon Theremin (born Lev Termen) between 1919 and 1920 in Leningrad. Thanks to him, the first compositions for electronic instruments were made, as opposed to those made by those who dedicated themselves to creating noise symphonies. In 1929, Joseph Schillinger composed his First Aerophonic Suite for Theremin and Orchestra, first performed by the Cleveland Orchestra and Leon Theremin as soloist.

Sound recording took a quantum leap in 1927 when American inventor J. A. O'Neill developed a recording device that used a type of magnetically coated tape. It was, however, a commercial disaster. However, the magnetic tape is also attributed to the German engineer Fritz Pfleumer who patented his discovery in 1929.

In addition to the theremin, an influential instrument that had a great influence on musical and film production due to its use as a soundtrack in science fiction and horror films of the 50s, another of the precursor instruments of electronic music was the Martenot waves. Invented in 1928 by Maurice Martenot, who made his debut in Paris, it consists of a keyboard, a loudspeaker, and a low-frequency generator whose sound is produced by a metal ring that the performer has to place on the index finger of his right hand..

In 1929, the American composer George Antheil created for the first time for mechanical devices, noise-producing devices, motors and amplifiers, an unfinished opera entitled Mr. Bloom.

The photo-optic method of sound recording used in the cinema, made it possible to obtain a visible image of the sound wave, as well as to synthesize a sound from a sound wave.

At the same time, experimentation with sound art began, early exponents of which include Tristan Tzara, Kurt Schwitters, and Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, among others.

1930-1939

Laurens Hammond founded a company dedicated to the manufacture of electronic instruments. Together with John M. Hanert, he first manufactured the Hammond organ, based on the principles of the telarmonium, in 1935, along with other developments such as the first reverberation units.

Development: 1940s and 1950s

Electroacoustic music on tape

Since about the year 1900, the low-fidelity magnetic wire tape recorder was created and used as a recording medium. In the early 1930s the film industry began to adapt to new optical sound recording systems based on photoelectric cells.

In the same decade the German electronics company AEG developed the first practical tape recorder, the Magnetophon K-1, first shown at the Berlin Radio Show in August 1935. During World War II (1939 -1945), Walter Weber rediscovered and applied the AC Bias technique that drastically increased the fidelity of magnetic recordings by adding an inaudible high frequency. In 1941 he extended the frequency curve of the Magnetophon K4 to 10 kHz and improved the signal-to-noise ratio to 60 dB, surpassing any recording system known at the time. By 1942, AEG was already conducting trials of recording in stereo. these devices and techniques were a secret outside of Germany until the end of World War II when several of these devices were requisitioned by Jack Mullin and brought to the United States. These served as the basis for the first professional tape recorders that were marketed in this country as the Model 200 produced by the Ampex company.

Music concrete (France)

The creation of magnetic audiotape opened up a vast field of sonic possibilities for musicians, composers, producers, and engineers. This new device was relatively cheap and its reproduction fidelity was better than any other audio medium known to date. It should be noted that, unlike records, it offered the same plasticity as celluloid used in movies: it can be slowed down, sped up, or even played backwards. It can also be physically edited, and different pieces of tape can even be joined into infinite loops that continuously play certain patterns of pre-recorded material. Audio amplification and mixing equipment further expanded the possibilities of tape as a production medium, allowing multiple recordings to be recorded at the same time on a different tape. Another possibility for tape was its ability to be easily modified to become echo machines, thus producing complex, controllable, and high-quality echo and reverberation effects that are virtually impossible to achieve by mechanical means.

Musicians soon began to use the tape recorder or tape recorder to develop a new composition technique called música concreta. This technique consists of editing fragments of sounds from nature or industrial processes recorded together. The first pieces of this music, recorded in 1948, were created by Pierre Schaeffer (1910-1995) with the collaboration of Pierre Henry (1927-2017). Composer, writer, teacher and music theorist and pioneer of radio and audiovisual communication Schaeffer performed the first concrete music concert at the École Normale de Musique in Paris on March 18, 1950. Later Pierre Henry collaborated with Schaeffer in the Symphonie pour un homme seul (1950) considered the first important work of concrete music. A year later Radiodiffusion-Télévision Française (RTF), the French public broadcasting organization, created in 1951 the first studio for the production of electronic music, an initiative that would also be developed in different countries becoming a global trend. Also in 1951, Schaeffer and Henry produced an opera, Orpheus, for specific sounds and voices.

Elektronische Musik (West Germany)

The birth and impulse of the so-called Elektronische Musik was mainly due to the works of the composer Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928-2007). Stockhausen worked briefly in Pierre Schaeffer's studio in 1952 and later, for several years, in the Electronic Music Studio of the Westdeutscher Rundfunk (WDR) in Cologne (Germany). the 1949 thesis Elektronische Klangerzeugung: Elektronische Musik und Synthetische Sprache, written by physicist Werner Meyer-Eppler, who conceived the idea of synthesizing music from electronically produced signals. In this way the Elektronische Musik differed notably from the French concrete music promoted by Schaeffer that used sounds recorded from acoustic sources.

The Electronic Music Studio of the Westdeutscher Rundfunk achieved international fame. Its foundation took place in 1951 when the physicist Werner Meyer-Eppler, the sound technician Robert Beyer and the composer Herbert Eimert convinced the director of the WDR, Hanns Hartmann, of the need for such a space. In the same year of its creation, the first studies of electronic music were broadcast in a program on the radio itself and presented at the Darmstadt Summer Courses. Under Eimert's leadership, the Studio became an international meeting place hosting composers such as Ernst Krenek (Austria/USA), György Ligeti (Hungary), Franco Evangelisti (Italy), Cornelius Cardew (England), Mauricio Kagel (Argentina) or Nam June Paik (South Korea).

In 1953 there was a public demonstration at the Cologne Radio concert hall where seven electronic pieces were performed. The electronic studio composers were Herbert Eimert, Karel Goeyvaerts, Paul Gredinger, Henry Pousseur and Karlheinz Stockhausen. The program included the following parts:

- Karlheinz Stockhausen: "Study II"

- Herbert Eimert: "Glockenspiel"

- Karel Goeyvaerts: "Composition No. 5"

- Henry Pousseur: "Sismograms"

- Paul Gredinger: «Formantes I y II»

- Karlheinz Stockhausen: "Study I"

- Herbert Eimert: "Study on Sound Mixes"

With Stockhausen and Mauricio Kagel as residents, the electronic music studio in Cologne became an emblem of avant-garde or avant-garde, when electronically generated sounds began to be combined with those of traditional instruments. In 1954 Stockhausen composed Elektronische Studie II the first electronic piece to be published as a soundtrack. Other significant examples are Mixtur (1964) and Hymnen, dritte Region mit Orchester (1967). Stockhausen stated that his listeners said that his electronic music gave them an experience of "outer space", sensations of flying, or of being in "a world fantastic dream".

The impact of the Cologne School has been significant on music history on three levels: studio is considered the "mother of all studios," Stockhausen's addition helped electronic music gain international respect, and Finally, many of the composers introduced to electroacoustic music in Cologne have developed the ideas they found there throughout their careers. In 2000 the studio was closed but that same year it was announced that an anonymous client had bought the building in which Stockhausen was born in 1928 and was renovating it with the initial intention of creating an exhibition space for modern art there. with the WDR Studio for Electronic Music museum installed on the first floor.

Electronic music in Japan

Although the first electronic instruments such as the Ondas Martenot, the Theremín or the Trautonio were little known in Japan before World War II, some composers such as Minao Shibata (1912-1996) or Tōru Takemitsu (1930-1996) had been aware of them at the time. Years later, different musicians in Japan began to experiment with electronic music, to which institutional support contributed, which allowed composers to experiment with the latest audio recording and processing equipment. These efforts gave rise to a musical form that fused Asian music with a new genre and would lay the foundation for Japanese dominance in the development of music technology for decades to come.

After the creation of the Sony company (known then as Tokyo Tsushin Kogyo K.K.) in 1946, Shibata and Takemitsu independently wrote about the possibility of using electronic technology to produce music in the late 1940s. In 1948, Takemitsu devised a technology that could bring noise into tempered musical tones and into a complex little tube, an idea similar to the music concrete that Pierre Schaeffer had ventured in the same year.. In 1949, Shibata wrote of his concept of "a musical instrument with great performance possibilities" that could "synthesize any kind of sound wave" and that it is "handled very easily," predicting that with an instrument like that, "the music scene would be drastically changed." That same year Sony developed the G-Type magnetic tape recorder.

In 1950 the electronic music studio Jikken Kōbō was founded by a group of musicians who wanted to produce experimental electronic music. Considered an avant-garde group, their members included Toru Takemitsu, Kuniharu Akiyama and Joji Yuasa, and they had the support of Sony, a company that offered access to their audio technology. The company hired Takemitsu to compose electroacoustic electronic music to display his tape recorders. Jikken Kōbō's first recordings, composed by Kuniharu Akiyama in 1951, were "Toraware no Onna" ("Prisoner Woman") and "Piece B". Many of the group's electroacoustic compositions were used as incidental music for radio, film, and music. plays. However, they also offered concerts in which they projected slides synchronized with a recorded soundtrack. Beyond the Jikken Kōbō Japan saw the development of many other composers such as Yasushi Akutagawa, Saburo Tominaga and Shiro Fukai who, in 1952 and 1953, were experimenting with electroacoustic music.

Many young composers want to write for orchestra but it is quite rare for them to interpret. Much of the audience has gone from new music, contemporary music, and this is the fault of the composers. In the 1950s and 1960s the new music was becoming very intellectual. (...) The mathematical form of building music is quite good, and has helped, but music is not mathematical. Music is for imagination. Now, many composers recognize the efforts of the 1950s and 60s. Now, we are not afraid to use atonality, dodecaphony and electronics. We can use everything. We can combine them in some eclectic form of composition that makes sense. Many composers are doing that, and I think it's good, but part of the music is written just to entertain, and just to have fun.Tōru Takemitsu

Music concrete was introduced to Japan by Toshirō Mayuzumi (1929-1997) who was influenced by attending a concert by Pierre Schaeffer. Beginning in 1952, he composed musical pieces for a comedy film, a radio program, and a radio soap opera However Schaeffer's sound object concept was not influential among Japanese composers who were primarily interested in overcoming the restrictions of human performance. This led to several Japanese electroacoustic musicians making use of serialism and twelve-tone techniques, evident in Yoshirō Irino's twelve-tone piece "Concerto da Camera" (1951) in the organization of electronic sounds in Mayuzumi's composition "X, Y, Z for Musique Concrète" or, later, in Shibata's electronic music in 1956.

In imitation of the Electronic Music Studio of the Westdeutscher Rundfunk, the founder of Karlheinz Stockhausen's Elektronische Musik, public broadcaster NHK has established an electronic music studio in Tokyo in 1955, which became one of the world's leading electronic music facilities. Promoted by Toshirō Mayuzumi, the studio was equipped with technologies such as tone generation and audio processing equipment, recording and radio equipment, Martenot, Monochord and Melochord waves, sinusoidal oscillators, tape recorders, ring modulators, bandpass filters, and sound mixers. four and eight track channels. Musicians associated with the studio included Mayuzumi, Minao Shibata, Joji Yuasa, Toshi Ichiyanagi, and Tōru Takemitsu. The studio's first electronic compositions were completed in 1955 including Mayuzumi's five-minute pieces "Studie I: Music for Sine Wave by Proportion of Prime Number”, “Music for Modulated Wave by Proportion of Prime Number” and “Invention for Square Wave and Sawtooth Wave”, produced employing the various tone-generating capabilities of the studio, and Shibata's 20-minute stereo piece "Musique Concrète for Stereophonic Broadcast".

Suddenly, in 1959, I became conservative. I heard the temple bells on New Year's Eve. They were so touching that I forgot contemporary music and started studying traditional music and aesthetics. I studied sintoism and Buddhism, not just Zen, but all Buddhism. I wrote the symphony "Nirvana" in 1959. I've been a traditional-minded composer.Toshirō Mayuzumi

Electronic music in the United States

The musical composition that is considered the origin of electronic music in the United States premiered at the beginning of 1939. The composer John Cage (1912-1992), one of the most notable artists of the genre in his country, he published Imaginary Landscape, No. 1. conventional instruments and electronic devices. While working on Seattle Cage experimented with the electronic equipment in the Cornish School recording studio and composed a part for Imaginary Landscape No. 1 which required the recordings of the record to be made on a variable speed turntable.. Between 1942 and 1952 Cage created five other compositions under the name Imaginary Landscape intended to be performed primarily as a percussion ensemble although Imaginary Landscape, No. 4 (1951) is for twelve radios and Imaginary Landscape, No. 5 (1952) uses 42 recordings and was made using magnetic tape as a physical medium.

A special case is the piece William Mix (or Williams Mix), in which eight loudspeakers were used, whose composition began in 1951. The composer and conductor Otto Luening indicated that it was a piece co-written by him and John Cage, although it is listed as a collaborative work of Cage completed in 1952. In 1954 Luening stated that it was performed, under the title William Mix, at a music festival held in Donaueschingen (Germany). According to Luening the reception of Williams Mix was a success where it made a "strong impression".

In 1951 with members of the New York School, the so-called The Music for Magnetic Tape Project was formed. Composed of John Cage, Earle Brown, Christian Wolff, David Tudor and Morton Feldman, their activities lasted for three years until 1954. Experimental and avant-garde in nature, the group lacked its own permanent facilities and had to depend on the free time that studios gave them. commercial sound, including the studio owned by Louis and Bebe Barron. About this project Cage reviewed: "In this social darkness (...) the work of Earle Brown, Morton Feldman and Christian Wolff continues to present a brilliant light, for the reason that the action is provocative in annotation, interpretation and audition". Already later, the use of electronically created sounds for different compositions, as exemplified by the piece Marginal Intersection (1951) by Morton Feldman. This piece is designed for winds, brass, percussion, strings, two oscillators, and sound effects.

There are different types of music, and the people who have said these things (hard reviews for their aggressive and provocative style) about what I do like a different kind of music. And most of them, I think what they like is a kind of music that is expressive of emotions and ideas. They're not so interested in sounds. Those critics are interested in feelings. And I like that feelings originate in every person.John Cage

Also in 1951 Columbia University (New York) acquired its first recorder, a professional Ampex machine, to record concerts. Vladimir Ussachevsky, who taught at the music faculty, was the person in charge of the device and almost immediately began to experiment with it. Herbert Russcol stated in this regard: "He was soon intrigued with the new sonorities that he could achieve by recording musical instruments and then superimposing them on each other". Ussachevsky later stated: "Suddenly I realized that the recorder could be treated as a sound transformation instrument". On Thursday, May 8, 1952, Ussachevsky performed, at Columbia University's McMillin Theater, various samples of tape music and effects that he created at the so-called Composers' Forum. These included transpose, reverb, experiment, composition, and underwater waltz. In an interview he stated: "I presented some examples of my discovery at a public concert in New York along with other compositions he had written for conventional instruments." Otto Luening, who had attended this concert, commented: " The equipment at his disposal consisted of an Ampex tape recorder and a simple box-shaped device designed by the brilliant young engineer Peter Mauzey to create feedback, a form of mechanical reverberation. The rest of the equipment was borrowed or purchased with personal funds".

In August 1952, Ussachevsky, invited by Luening, traveled to Bennington (Vermont) to present his experiments. There both collaborated on several pieces. Luening described the event: "Equipped with headphones and a flute, I began to develop my first composition for the recorder. We both improvised fluently and the medium fired our imaginations'. They played some of the early pieces informally at a party where "several composers congratulated us almost solemnly saying: 'This is it' ('it' means the music of the future)'. Word quickly reached New York City. Oliver Daniel phoned and invited the couple to "produce a group of short compositions for the October concert sponsored by the American Composers Alliance and Broadcast Music, Inc., under the direction of Leopold Stokowski at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Henry Cowell made his home and studio in Woodstock available to us. With borrowed gear in the back of Ussachevsky's car, we left Bennington for Woodstock and stayed for two weeks. At the end of September 1952 the traveling laboratory arrived at Ussachevsky's New York living room, where we finally completed the compositions". Two months later, on October 28, Vladimir Ussachevsky and Otto Luening presented the first concert of music recorded in the United States. The concert included Luening's Fantasy in Space (1952), "an impressionistic piece of virtuosity" which employs manipulated recordings of flute, and Low Speed (1952), an "exotic composition that took the flute far below its natural range". After several concerts caused a sensation in New York City, Ussachevsky and Luening were invited to a live broadcast of NBC's Today Show to do an interview and perform the first televised electro-acoustic performance. Luening described the event: 'I improvised some [flute] sequences for the recorder. Ussachevsky at that time subjected them to electronic transformations".

Stochastic Music

The appearance of computers as equipment used to compose music represented an important development of electronic music as opposed to the manipulation or creation of sounds. The Romanian composer of Greek origin Iannis Xenakis (1922-2001) founded the so-called stochastic music (musique stochastique) characterized by a compositional method that uses stochastic probability mathematical algorithms whose result is the creation of pieces under a set of parameters. With ideas contrary to totalitarianism, Xenakis fought in the Greek Resistance movement in World War II and, after escaping a death sentence, settled in Paris in 1947. The French capital will be his center of work both in his musical development and in his facets as a mathematician and architect as a collaborator of Le Corbusier. Xenakis used graph paper and a ruler to help him calculate the speed of the glissando trajectories for his orchestral composition Metastasis (1953-1954), later using computers to compose pieces such as ST/ 4 for string quartet and ST/48 for orchestra. Other notable works throughout his career include Nomos Alpha (1965), Cenizas (1974) and Shaar (1982).

Many then thought that my music should be a cold music, since there were mathematics in it. And they stopped taking into account what they heard. This incomprehension came to afflict me a lot. (...) In this sense, music is probably the art in which dialogue with itself is more difficult (...) pointing to absolute creation, without reference to anything known, as a cosmic phenomenon, or going further, dragging in an intimate and secret way into a kind of abyss in which, happily, the soul is absorbed. (...) For this reason, it is necessary to invent the architectural form that frees the collective hearing of all its inconveniences."Iannis Xenakis

Electronic music in Australia

In Australia, the world's first computer capable of interpreting music was developed. Called CSIRAC, it was a prototype released in 1949 designed and built by Trevor Pearcey and Maston Beard. The mathematician Geoff Hill programmed the computer to play popular musical melodies from the early 1950s. In 1951 he performed in public the piece Colonel Bogey March , of which no recordings survive, but a reconstruction. exact.

However, the CSIRAC was simply used as a computer capable of interpreting a standard musical repertoire but was not used for other practices such as composition as if done by Iannin Xenakis. Performances recorded with this computer were never recorded, although accurately reproduced reconstructions of the music do exist. The earliest known recordings of computer-generated music were performed by the Ferranti Mark I computer, a commercial, non-educational version of the Baby Machine computer created by the University of Manchester in the autumn of 1951. The music program performed for the Ferranti Mark I was written by Christopher Strachey.

Mid to late 1950s

In 1955 more electronic and experimental studies appeared. Important were the creation of the Study of Phonology, a studio at the NHK in Tokyo, and the Phillips studio in Eindhoven, the Netherlands, which moved to the University of Utrecht as the Institute of Sonology in 1960.

The impact of computers continued through 1956. Lejaren Hiller and Leonard Isaacson composed Iliac Suite for a string quartet, the first complete work to be composed with the assistance of a computer using an algorithm in the composition. Later developments included the work of Max Mathews at Bell Laboratories, who developed the influential MUSIC I program. Vocoder technology was another important development of this time.

In 1956, Stockhausen composed Gesang der Jünglinge, the first major work of the Cologne studio, based on a text from the Book of Daniel. An important technological development was the invention of the Clavivox synthesizer by Raymond Scott, with assembly by Robert Moog.

Another of the milestones of American electronic music was the publication of the soundtrack of Forbidden Planet (1956) composed and produced by Louis and Bebe Barron. Science fiction film, directed by Fred M. Wilcox and starring Walter Pidgeon, Anne Francis and Leslie Nielsen, the music composed was made using only custom electronic circuitry and sound recorders. Despite the lack of synthesizers, in the contemporary sense, since this instrument would take a few years to develop, its impact on popular culture was notable since it was the first time that a major Hollywood studio opted for this type of sound for one of his projects. However, it was not well received by the American Federation of Musicians, due to the fact that it did not have an orchestral arrangement, which motivated those avant-garde compositions to be called "electronic tonalities" instead of "music".

The RCA Mark II Sound Synthesizer appeared in 1957. Unlike the early Theremin and Ondes Martenot, this one was difficult to use as it required extensive programming and could not be played in real time. Sometimes called the first electronic synthesizer, the RCA Mark II Sound Synthesizer used thermionic valve oscillators and incorporated the first sequencer. It was designed by RCA and installed at the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center, where it remains today. Subsequently, Milton Babbitt, influenced in his student years by the "revolution in musical thought" de Schoenberg, began to apply serial techniques to electronic music.

Expansion: 1960s

These were fertile years for electronic music, not only for academic music but also for some independent artists as synthesizer technology became more accessible. By this time, a powerful community of composers and musicians working with new sounds and instruments had been established and was growing. During these years compositions such as Luening's Gargoyle for violin and tape appear, as well as Stockhausen's Kontakte premiere for electronic sounds, piano and percussion. In the latter, Stockhausen abandoned the traditional musical form based on a linear development and a dramatic climax. In this new approach, which he called "moment form", he recalls the cinematic splice techniques of early-century cinema XX.

The first of these synthesizers to appear was the Buchla, in 1963, being the product of the effort of the concrete music composer Morton Subotnick.

The Theremin had been used since the 1920s, maintaining a certain popularity thanks to its use in numerous science fiction movie soundtracks of the 1950s (for example: The Day the Earth Stood Still by Bernard Hermann). During the 1960s, the Theremin made occasional appearances in popular music.

In the UK, during this period, the BBC Radiophonic Workshop (established in 1958) emerged as one of the most productive and renowned studios in the world, thanks to its work on the science fiction series Doctor Who. One of the most influential British electronic artists of this period was Delia Derbyshire. She is famous for her iconic 1963 performance of the Doctor Who theme song, composed by Ron Grainer and recognized by some as the best-known piece of electronic music in the world. Derbyshire and his colleagues, including Dick Mills, Brian Hodgson (creator of the TARDIS sound effect), David Cain, John Baker, Paddy Kingsland and Peter Howell, developed a vast body of work including soundtracks, atmospheres, symphonies of programs and sound effects for BBC TV and its radio stations.

In 1961, Josef Tal created the Center for Electronic Music in Israel at the Hebrew University, and in 1962 Hugh Le Caine came to Jerusalem to set up his Creative Tape Recorder in the center.

Milton Babbitt composed his first electronic work using the synthesizer, which was created through the RCA at CPEMC. The collaborations were carried out overcoming the barriers of the oceans and continents. In 1961, Ussachevsky invited Varèse to the Columbia-Princeton Studio (CPEMC), being assisted by Mario Davidovsky and Bülent Arel. The intense activity of the CPEMC, among others, inspired the creation in San Francisco of the Tape Music Center in 1963, by Morton Subotnick together with other additional members, such as Pauline Oliveros, Ramón Sender, Terry Riley and Anthony Martin. A year later, the First Electronic Music Seminar in Czechoslovakia took place, organized at the Radio Broadcast Station in Plzen.

From this point on, new instruments continued to be developed, with one of the most important breakthroughs taking place in 1964, when Robert Moog introduced the Moog synthesizer, the first analog synthesizer controlled by an integrated modular voltage control system. Moog Music later introduced a smaller synthesizer with a keyboard called the Minimoog, which was used by many songwriters and universities, thus becoming very popular. A classic example of the use of the oversized Moog is the album Switched-On Bach, by Wendy Carlos.

In 1966, Pierre Schaeffer founded the Groupe de Recherches Musicales (Musical Research Group) for the study and research of electronic music. Its programming is structured based on a commitment to the processes of dissemination, research and creation of contemporary music and the most current trends in video art and image. Its exhibitions and concerts are reproduced in real time through electronic devices, audio-video interfaces and a staff of national and international musicians and video artists open to the use of cutting-edge technologies.

Music by computer

CSIRAC, the first computer to play music, performed this act publicly in August 1951. One of the first large-scale demonstrations of what became known as computer music was a nationally broadcast pre -recorded on the NBC network for the Monitor program on February 10, 1962. A year earlier, LaFarr Stuart programmed the Iowa State University CYCLONE computer to play simple, recognizable songs through an amplified speaker attached to a system originally used for administrative and diagnostic issues.

The 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s also saw the development of large operating frameworks for computer synthesis. In 1957, Max Mathews of Bell Labs developed the MUSIC program, culminating in a direct digital synthesis language.

In Paris, IRCAM became the leading research center for computer-generated music, developing the Sogitec 4X computer system which included a revolutionary real-time digital signal processing system. Répons (1981), a work for 24 musicians and 6 soloists by Pierre Boulez, used the 4X system to transform and direct the soloists towards a loudspeaker system.

Live electronic music

In the United States, live electronica was first performed in the 1960s by members of Milton Cohen's Space Theater in Ann Arbor, Michigan, including Gordon Mumma, Robert Ashley, David Tudor and The Sonic Arts Union, founded in 1966 by those named above, also including Alvin Lucier and David Behrman. The ONCE festivals, showcasing multimedia music for theater, were organized by Robert Ashley and Gordon Mumma in Ann Arbor between 1958 and 1969. In 1960, John Cage composed Cartridge Music, one of the first works of electronica. live.

Jazz composers and musicians, Paul Bley and Annette Peacock, were among the first to perform in concert using Moog synthesizers in the late 1960s. Peacock made regular use of an adapted Moog synthesizer to process his voice both on stage as in studio recordings.

As time passed, social events began to form that tried to bring together a large number of concerts with various live artists. So far there are many festivals that have manifested the electronic scene, many of them setting records for massive attendance at the event. Some of the most representative and outstanding festivals of the genre are:

- Love Parade

- Tomorrowland (festival)

- Ultra Music Festival

- Street Parade

- Qlimax

- Defqon.1

- Electric Daisy Carnival

- Life in Color

- I Love Techno

- Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival

- Trance Energy

- Barcelona Beach Festival

- Creamfields

- I love the 90s.

Currently, mega-festivals continue to emerge that seek to expand the essence of the electronic genre.

Synthesizers

Robert Moog (also known as Bob Moog), in late 1963, met experimental composer Herbert Deutsch, who, in his search for new electronic sounds, inspired Moog to create his first synthesizer, the Moog Modular Synthesizer.

The Moog, while previously known to the music and educational community, was introduced to society in the fall of 1964, when Bob gave a demonstration at the Audio Engineering Society Convention in Los Angeles. At this convention, Moog already received its first orders and business took off.

The Moog Music company grew spectacularly during the first few years, becoming even better known when Wendy Carlos released the album Switched on Bach. Bob designed and marketed new models, such as the Minimoog (the first portable version of the Moog Modular), the Moog Taurus (octave-spread pedal keyboard, with transpose for bass and treble), the PolyMoog (first 100% polyphonic model), the MemoryMoog (polyphonic, equaled six MiniMoog's in one), the MinitMoog, the Moog Sanctuary, etc.

Moog failed to manage his business well and it went from having nine-month waiting lists to no orders at all. Overwhelmed by debt, he lost control of the company and it was acquired by an investor. Even so, he continued to design musical instruments until 1977, when he left Moog Music and moved to a small town in the Appalachian Mountains. Moog Music collapsed soon after.

In 1967, Kato approached engineer Fumio Mieda, who wanted to start building musical keyboards. Fueled by Mieda's enthusiasm, Kato asked him to build a prototype keyboard, and 18 months later, Mieda presented him with a programmable organ. The Keio company sold this organ under the Korg brand, made from the combination of its name with the word organ, in English Organ.

Keio-produced organs were successful in the late 1960s and early 1970s, but mindful of competition from large, established organ manufacturers, Kato decided to use electronic organ technology to build keyboards aimed at the synthesizer market. In fact, the first Keio synthesizer (MiniKorg) was introduced in 1973. Following the success of this instrument, Keio introduced various low-cost synthesizers during the 1970s and 1980s under the Korg brand.

Late 1960s - early 1980s

In 1970, Charles Wuorinen composed Time's Encomium, thus becoming the first winner of the Pulitzer Prize for an all-electronic composition. The 1970s also saw the widespread use of synthesizers in rock music, with examples such as: Pink Floyd, Tangerine Dream, Yes and Emerson, Lake & palmers etc.

Birth of popular electronic music

Throughout the 1970s, bands like The Residents and Can pioneered an experimental music movement that incorporated elements of electronic music. Can was one of the first groups to use tape loops for the rhythm section, while The Residents created their own drum machines. Also around this time different rock bands, from Genesis to The Cars, began to incorporate synthesizers into their rock arrangements.

In 1979, musician Gary Numan helped bring electronic music to a wider audience with his pop hit Cars, from the album The Pleasure Principle. Other groups and artists who contributed significantly to popularizing music created exclusively or mainly electronically were Kraftwerk, Depeche Mode, Jean Michel Jarre, Mike Oldfield or Vangelis.

Birth of MIDI

In 1980, a group of musicians and manufacturers agreed to standardize an interface through which different instruments could communicate with each other and with the main computer. The standard was called MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface). In August 1983, the MIDI 1.0 specification was finalized.

The advent of MIDI technology allowed that with the simple act of pressing a key, controlling a wheel, moving a pedal or giving an order on a microcomputer, each and every studio device could be activated remotely and synchronized way, each device responding according to the conditions pre-set by the composer.

Miller Puckette developed 4X graphical signal processing software called Max, which would later be incorporated into the Macintosh for real-time MIDI control, making algorithmic composition available to any composer with even the slightest knowledge of MIDI. computer programming.

Digital synthesis

In 1979, the Australian company Fairlight released the Fairlight CMI (Computer Musical Instrument), the first practical digital polyphonic sampler system. In 1983, Yamaha introduced the first standalone digital synthesizer, the DX-7, which used frequency modulation synthesis (FM synthesis), first tested by John Chowning at Stanford in the late 1960s.

Late 1980s - 1990s

Growth of dance music

Towards the end of the 1980s, dance music records using exclusively electronic instrumentation became increasingly popular. This trend has continued up to the present, being common to listen to electronic music in clubs all over the world.

Advancement in music

In the 1990s, it became possible to carry out performances with the assistance of interactive computers. Another recent breakthrough is Tod Machover's (MIT and IRCAM) composition Begin Again Again for hyper cello, an interactive system of sensors that measure the cellist's physical movements. Max Methews developed the Conductor program for real-time control of the tempo, dynamics, and timbre of an electronic track.

21st century

As computer technology becomes more accessible and music software advances, music production is possible using means unrelated to traditional practices. The same goes for concerts, extending his practice using laptops and live coding. The term Live PA is popularized to describe any type of live performance of electronic music, whether using a computer, synthesizer or other devices.

In the 1990s and 2000s, different virtual studio environments built on software emerged, including products such as Reason, by Propellerhead, and Ableton Live, which are becoming increasingly popular. These tools provide useful and inexpensive alternatives to hardware based production studios. Thanks to advances in microprocessor technology, it is becoming possible to create high-quality music using little more than a single computer. These advances have democratized musical creation, thus increasing massively and making it available to the public on the internet.

The advance of software and virtual production environments has led to a whole series of devices, formerly only existing as hardware, are now available as virtual parts, tools or plugins of the software. Some of the more popular software are Max/Msp and Reaktor, as well as open source packages such as Pure Data, SuperCollider and ChucK.

Advances in the miniaturization of electronic components, which once made instruments and technologies more accessible only to musicians with deep pockets, have led to a new revolution in the electronic tools used for music creation. For example, during the 90s, mobile phones incorporated monophonic tone generators that some factories used not only to generate the Ringtones of their equipment, but also allowed their users to have some musical creation tools. Subsequently, the increasingly small and powerful laptops, pocket computers and personal digital assistants (PDAs) paved the way for today's tablets and smartphones that allow not only the use of tone generators, but that of other tools such as samplers, monophonic and polyphonic synthesizers, multitrack recording, etc. The ones that allow music creation almost anywhere.

Contenido relacionado

Programmable Read Only Memory

Internal combustion engine

Faraday cage