El Greco

Doménikos Theotokópoulos (in Greek Δομήνικος Θεοτοκόπουλος; Candia, October 1, 1541-Toledo, April 7, 1614), known as el Greco ("the Greek"), was a painter of the end of the Renaissance who developed a very personal style in his mature works.

Until he was 26 years old, he lived in Crete, where he was an appreciated master of icons in the post-Byzantine style in force on the island. He then lived for ten years in Italy, where he came into contact with Renaissance painters, first in Venice, fully assuming the style of Titian and Tintoretto, and later in Rome, studying the mannerism of Michelangelo. In 1577 he settled in Toledo (Spain), where he lived and worked the rest of his life.

His pictorial training was complex, obtained in three very different cultural foci: his early Byzantine training was the cause of important aspects of his style that flourished in his maturity; the second was obtained in Venice from the painters of the high Renaissance, especially from Titian, learning oil painting and its range of colors - he always considered himself part of the Venetian school -; Finally, his stay in Rome allowed him to get to know the work of Michelangelo and mannerism, which became his vital style, interpreted in an autonomous way.

His work consists of large canvases for church altarpieces, numerous devotional paintings for religious institutions, in which his workshop often participated, and a group of portraits considered to be of the highest level. In his first Spanish masterpieces the influence of his Italian masters can be appreciated. However, he soon evolved towards a personal style characterized by his extraordinarily elongated mannerist figures with their own lighting, thin, ghostly, very expressive, in indefinite environments and a range of colors seeking contrasts. This style was identified with the spirit of the Counter-Reformation and became extreme in its last years.

Today he is considered one of the greatest artists of Western civilization. This high regard is recent and was formed throughout the 20th century, changing the appreciation of his painting formed in the two and a half centuries that followed his death, in which he came to be considered an eccentric and marginal painter in art history.

Biography

Crete

Doménikos Theotokópoulos was born on October 1, 1541 in Candia (present-day Heraklion) on the island of Crete, which was then a possession of the Republic of Venice. His father, Geórgios Theotokópoulos, was a merchant and tax collector and his older brother, Manoússos Theotokópoulos, was also a merchant.

Doménikos studied painting on his native island, becoming an icon painter in the post-Byzantine style prevailing in Crete at the time. At the age of twenty-two, he was described in a document as "maestro Domenigo", which means that he was already officially practicing the profession of painter. In June 1566, he signed as a witness in a contract with the name Master Ménegos Theotokópoulos, painter (μαΐστρος Μένεγος Θεοτοκόπουλος σγουράφος). Ménegos was the Venetian dialectal form of Doménicos.

The post-Byzantine style was a continuation of traditional Greek Orthodox icon painting from the Middle Ages. They were devotional cadres that followed fixed rules. His characters were copied from well-established artificial models, not at all natural or penetrating psychological analysis, with gold as the background of the paintings. These icons were not influenced by the new naturalism of the Renaissance.

At twenty-six years of age he still resided in Candia, and his works must have been highly esteemed. In December 1566, El Greco asked the Venetian authorities for permission to sell a "panel of the Passion of Christ executed on a gold background" at auction. This Byzantine icon of the young Doménikos was sold for the price of 70 gold ducats, equal in value to a work by Titian or Tintoretto from the same period.

Among the works from this period is the Death of the Virgin (Dormitio Virginis), kept in the Church of the Dormition, in Syros. Also from this period, two other icons have been identified, only with the signature of "Domenikos": Saint Luke painting the Virgin and The Adoration of the Magi i>, both in the Benaki Museum in Athens. In these works one sees an incipient interest of the artist in introducing the formal motifs of Western art, all known from the Italian engravings and paintings that arrived in Crete. The Modena Triptych from the Estense Gallery in Modena, located between the periods of Crete and Venice, represents the artist's gradual abandonment of oriental art codes and the progressive mastery of western art resources.

Some historians accept that his religion was Orthodox, although other scholars believe that he was part of the Cretan Catholic minority or that he converted to Catholicism before leaving the island.

Venice

He must have moved to Venice around 1567. As a Venetian citizen it was natural for the young artist to continue his training in that city. Venice, at that time, was the largest artistic center in Italy. There the supreme genius of Titian worked intensely, expending the last years of his life in the midst of universal recognition.Tintoretto, Paolo Veronese and Jacopo Bassano also worked in the city and it seems that El Greco studied the work of all of them.

The brilliant and colorful Venetian painting must have had a strong impact on the young painter, trained until then in the artisan and routine technique of Crete. El Greco did not do like other Cretan artists who had moved to Venice, the madoneros, painting in the Byzantine style with Italian elements. From the beginning he assumed and painted with the new pictorial language learned in Venice, becoming a Venetian painter. Possibly he was able to learn in Titian's workshop the secrets of Venetian painting, so different from Byzantine: the architectural backgrounds that give depth to the compositions, the drawing, the naturalistic color and the way of lighting from certain sources.

In this city he learned the basic principles of his pictorial art that were present throughout his artistic career. Painting without prior drawing, fixing the composition on the canvas with synthetic brushstrokes with black pigment, and turning color into one of the most important resources of his artistic style. In this period, El Greco used engravings to solve his compositions.

Among the best-known works of his Venetian period is the Healing of the Blind Born (Gemäldegalerie, Dresden), in which the influence of Titian in the treatment of color and that of Tintoretto can be perceived in the composition of figures and the use of space.

Rome

Then the painter headed for Rome. On his way, he must have stopped in Parma to learn about Correggio's work, since his praiseworthy comments towards this painter (he called him a "unique figure in painting") show direct knowledge of his art.

His arrival in Rome is documented in a letter of introduction from the miniaturist Giulio Clovio to Cardinal Alejandro Farnesio, dated November 16, 1570, where he asked him to host the painter in his palace for a short time until he found another accommodation. Thus began this letter: "A young Candiot has arrived in Rome, a disciple of Titian, who in my opinion ranks among the excellent in painting." Historians seem to accept that the term "disciple of Titian" does not mean that he was in his workshop but was an admirer of his painting.

Through the cardinal's librarian, the scholar Fulvio Orsini, he came into contact with the city's intellectual elite. Orsini came to own seven paintings by the artist (View of Mount Sinai and a portrait of Clovio are among them).

El Greco was expelled from the Farnese Palace by the cardinal's butler. The only known information about this incident is a letter from El Greco sent to Alejandro Farnesio on July 6, 1572, denouncing the falsity of the accusations made against him. In that letter he said: "in no way did he deserve through my fault to be later expelled and thrown in this way." On September 18 of that same year, he paid his dues to the Academy of San Lucas as a miniature painter. That year, El Greco opened his own workshop and hired the painters Lattanzio Bonastri from Lucignano and Francisco Proboste as assistants. The latter worked with him until the last years of his life.

When El Greco lived in Rome, Michelangelo and Raphael were dead, but their enormous influence continued. The heritage of these great masters dominated the art scene in Rome. Roman painters by the 1550s had established a style called full mannerism or maniera based on the works of Raphael and Michelangelo, where the figures were exaggerated and complicated until they became artificial, seeking a precious virtuosity. On the other hand, the reforms of the doctrine and of the Catholic practices initiated in the Council of Trent began to condition religious art.

Julio Mancini wrote years later, around 1621, in His Considerations, among many other biographies, that of El Greco, being the first to be written about him. Mancini wrote that “the painter was commonly called Il Greco (The Greek), that he had worked with Titian in Venice and that when he arrived in Rome his works were greatly admired and some it was confused with those painted by the Venetian master. He also recounted that he was thinking of covering some nude figures from Michelangelo's Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel that Pope Pius V considered indecent, and he (El Greco) burst out in saying that if all the the work, he could do it with honesty and decency and not inferior to it in good pictorial execution... All the painters and lovers of painting were outraged, it was necessary for him to go to Spain... ». The scholar De Salas, referring to this comment by El Greco, highlights the enormous manifestation of pride that meant considering himself at the same level as Michelangelo, who at that time was the most exalted artist in art. To understand this manifestation, it must be noted that they existed in Italy two schools with very different criteria: that of the followers of Michelangelo advocated the primacy of the drawing in the painting; and Titian's Venetian indicated the superiority of color. The latter was defended by El Greco.

This contrary opinion about Michelangelo is misleading, since El Greco's aesthetics was profoundly influenced by Michelangelo's artistic thought, dominated by a major aspect: the primacy of imagination over imitation in artistic creation. In El Greco's writings, it can be seen that he fully shared the belief in an artificial art and the Mannerist criteria of beauty.

Today, his Italian nickname Il Greco has been transformed and he is universally known as el Greco, changing the Italian article Il to the Spanish one the. However, his paintings were always signed in Greek, usually with his full name Domenikos Theotokopoulos.

The Italian period is considered a time of study and preparation, since his genius did not emerge until his first works in Toledo in 1577. In Italy, he did not receive any important commissions, since he was a foreigner, and Rome was dominated by painters such as Federico Zuccaro, Scipione Pulzone and Girolamo Siciolante, of lesser artistic quality but better known and better situated. In Venice it was much more difficult, because the three greats of Venetian painting, Titian, Tintoretto and Veronese, were at their peak.

Among the main works of his Roman period are: the Purification of the Temple; various portraits —such as the Portrait of Giulio Clovio (1570-1575, Naples) or of the governor of Malta Vincentio Anastagi (circa 1575, New York, Frick Collection)—; He also executed a series of works deeply marked by his Venetian apprenticeship, such as The Informant (c. 1570, Naples, Capodimonte Museum) and the Annunciation (c. 1575, Madrid, Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum).

It is not known how long he remained in Rome. Some scholars defend a second stay in Venice (c. 1575-1576), before going to Spain.

In Spain

Arrival in Toledo and first masterpieces

At that time the monastery of El Escorial, near Madrid, was being completed and Felipe II had invited the artistic world of Italy to come and decorate it. Through Clovio and Orsini, El Greco met Benito Arias Montano, a Spanish humanist and delegate of Philip II, the clergyman Pedro Chacón and Luis de Castilla, natural son of Diego de Castilla, dean of the cathedral of Toledo. Greco with Castilla would ensure his first important commissions in Toledo.

In 1576 the artist left Rome and after passing through Madrid he arrived in Toledo in the spring or perhaps in July of 1577. It was in this city that he produced his mature works. Toledo, in addition to being the religious capital of Spain At that time it was also one of the largest cities in Europe. In 1571 the city's population was about 62,000.

The first important commissions in Toledo came to him immediately: the main altarpiece and two lateral ones for the church of Santo Domingo el Antiguo in Toledo. These altarpieces include The Assumption of the Virgin (Art Institute of Chicago) and The Trinity (Museo del Prado). He was also hired simultaneously El expolio , for the sacristy of the cathedral.

In the Assumption, based on the composition of the Assumption by Titian (Church of Santa Maria dei Frari, Venice), the personal style of the painter appears, but the approach is fully Italian. There are also references to Michelangelo's sculptural style in The Trinity, with Italian Renaissance overtones and a marked Mannerist style. The figures are elongated and dynamic, arranged in a zigzag pattern. The anatomical and human treatment of figures of a divine nature, such as Christ or the angels, is surprising. The colors are acid, incandescent and morbid and, together with a play of contrasting lights, give the work a mystical and dynamic air. The turn towards a personal style, differentiating from his masters, begins to emerge in his work, using less conventional colours, more unorthodox groupings of characters and unique anatomical proportions.

These works would establish the painter's reputation in Toledo and gave him great prestige. From the beginning he had the confidence of Diego de Castilla, as well as clergymen and intellectuals from Toledo who recognized his worth. But on the other hand, his commercial relations with his clients were complicated from the beginning due to the lawsuit over the value of The looting , since the cathedral chapter valued it at much less than what what the painter intended.

El Greco did not plan to settle in Toledo, as his objective was to obtain the favor of Philip II and make a career at court. In fact, he obtained two important commissions from the monarch: Adoration of the name of Jesus (also known as the Allegory of the Holy League or Dream of Philip II) and The Martyrdom of Saint Maurice and the Theban Legion (1578 -1582), both still in the monastery of El Escorial today. In the Allegory he showed his ability to combine complex political iconography with medieval orthodox motifs. Neither of these two works pleased the king, so he did not commission him any more.As Fray José de Sigüenza, a witness to the events, wrote, "the painting of Saint Mauricio and his soldiers... did not satisfy the public." majesty of him."

Maturity

Lacking royal favor, El Greco decided to remain in Toledo, where he had been received in 1577 as a great painter.

In 1578 his only son, Jorge Manuel, was born. His mother was Jerónima de las Cuevas, whom he never married and who is believed to have been portrayed in the painting The Lady in Ermine .

On September 10, 1585, he leased three rooms in a palace belonging to the Marquis of Villena, which was subdivided into apartments. He lived there, except for the period between 1590 and 1604, for the rest of his life.

In 1585, the presence of his assistant in the Roman period, the Italian painter Francisco Proboste, is documented, and he had established a workshop capable of producing complete altarpieces, that is, paintings, polychrome sculpture and gilded wood architectural frames.

On March 12, 1586, he was commissioned The Burial of the Count of Orgaz, today his best-known work. The painting, made for the church of Santo Tomé in Toledo, is still in instead. It shows the burial of a Toledo nobleman in 1323, who according to a local legend was buried by Saints Esteban and Agustín. The painter anachronistically represented local figures from his time in the procession, also including his son. At the top, the soul of the dead ascends to heaven, densely populated with angels and saints. The burial of the Count of Orgaz already shows its characteristic longitudinal elongation of the figures, as well as the horror vacui (fear of the void), aspects that they would become more and more accused as El Greco aged. These traits stemmed from mannerism, and persisted in El Greco's work even though they had been abandoned by international painting a few years earlier.

The payment for this painting also led to another lawsuit: the price at which it was appraised, 1,200 ducats, seemed excessive to the parish priest of Santo Tomé, who requested a second appraisal settling at 1,600 ducats. The parish priest then requested that this second appraisal not be taken into account, accepting El Greco to charge only 1,200 ducats. Disputes over the price of his important works were a constant feature in El Greco's professional life and have given rise to numerous theories to explain it.

The period of his life between 1588 and 1595 is poorly documented. From 1580 he painted religious subjects, among which his canvases on saints stand out: Saint John the Evangelist and Saint Francis (c. 1590-1595, Madrid, private collection), The Tears of Saint Peter, The Holy Family (1595, Toledo, Hospital Tavera), San Andrés and San Francisco (1595, Madrid, Museo del Prado) and Saint Jerome (beginning of the XVII century AD, Madrid, private collection) Another high-quality Saint Jerome dated 1600 is preserved in the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando, comparable only to the one preserved in the National Gallery of Scotland. He also made portraits such as The gentleman with his hand on his chest (1585, Madrid, Museo del Prado).

Last period

From 1596 there was a great increase in commissions that was maintained until his death. The reasons are several: the reputation achieved by the artist in previous years, the prestige and friendship with a group of local patrons who regularly provided him with important commissions and also, since 1600, the participation in the workshop of his son Jorge Manuel, who got commissions in the towns near Toledo. The last decade of the 16th century d. C. was a crucial period in his art because his late style was developed in it.

Although the patrons he initially sought, King Philip II and the cathedral, which would have provided him with a secure and lucrative position, had failed him, in the end he found his patrons in a group of churchmen whose goal was to propagate the doctrine of the Counter-Reformation, since El Greco's career coincided with the moment of the Catholic reaffirmation against Protestantism promoted by the Council of Trent, with the Archdiocese of Toledo being the official center of Spanish Catholicism. Thus, El Greco illustrated the ideas of the Counter-Reformation, as can be seen in his repertoire of themes: representations of saints, as the Church defended as intercessors for men before Christ; penitents who stressed the value of the confession that the Protestants rejected; the glorification of the Virgin Mary, also questioned by Protestants; for the same reason the paintings on the Sagrada Família were highlighted. El Greco was an artist who served the ideals of the Counter-Reformation by designing altarpieces that displayed and highlighted the main Catholic devotions.

The painter's fame attracted many clients who requested replicas of his best-known works. These copies, made in large numbers by his workshop, still create confusion today in the catalog of his authentic works.

In 1596 he signed the first important commission of this period, the altarpiece for the church of an Augustinian seminary in Madrid, the Colegio de doña María de Aragón, paid for with funds that this lady specified in her will. with another important work, three altarpieces for a private chapel in Toledo dedicated to Saint Joseph. These altarpieces include the paintings Saint Joseph with the Child Jesus, Saint Martin and the beggar and the Virgin with the Child and Saints Inés and Martina. His figures are increasingly elongated and twisted, his paintings narrower and taller, his very personal interpretation of mannerism reaches its culmination.

Through his son, in 1603 he obtained a new contract to carry out the altarpiece of the Hospital de la Caridad de Illescas. For unknown reasons he agreed to have the final appraisal done by appraisers appointed by the Hospital. They set a very low price of 2,410 ducats, which led to a long lawsuit that reached the Royal Chancellery of Valladolid and the Papal Nuncio in Madrid. The dispute ended in 1607 and, although intermediate appraisals of around 4,000 ducats were made, in the end an amount similar to that initially established was paid. Illescas' setback seriously affected El Greco's economy, who had to resort to a loan of 2,000 ducats from his friend Gregorio de Angulo.

At the end of 1607, El Greco offered to finish the chapel of Isabel de Oballe, which had remained unfinished due to the death of the painter Alessandro Semini. The artist, now 66 years old, undertook to correct the proportions of the altarpiece and replace a Visitation, without additional expenses. The Immaculate Conception for this chapel is one of his great late works, the lengthenings and The writhings have never before been so exaggerated or so violent, the elongated shape of the painting matches the figures that rise towards the sky, far from the natural forms.

His last important altarpieces included a main altarpiece and two lateral ones for the chapel of the Hospital Tavera, being contracted on November 16, 1608 with an execution period of five years. The fifth seal of the Apocalypse, canvas for one of the side altarpieces, shows the genius of El Greco in his last years.

In August 1612, El Greco and his son agreed with the nuns of Santo Domingo el Antiguo to have a chapel for the family burial. For her, the artist made The Adoration of the Shepherds. It is a masterpiece in all its details: the two shepherds on the right are very elongated, the figures express amazement and adoration in a moving way. The light stands out giving each character importance in the composition. The nocturnal colors are bright and with strong contrasts between red-orange, yellow, green, blue and pink.

On April 7, 1614, he died at the age of seventy-three, being buried in Santo Domingo el Antiguo. A few days later, Jorge Manuel made a first inventory of the few assets of his father, including the finished and ongoing works that were in the workshop. Later, on the occasion of his second marriage in 1621, Jorge Manuel carried out a second inventory that included works not registered in the first. The pantheon had to be transferred before 1619 to San Torcuato, due to a dispute with the nuns of Santo Domingo, and was destroyed when the church was demolished in the 19th century AD. C..

Her life, full of pride and independence, always tended to consolidate her particular and strange style, avoiding imitations. He collected valuable volumes, which made a wonderful library. A contemporary defined him as a "man of eccentric habits and ideas, tremendous determination, extraordinary reticence, and extreme devotion." Due to these or other characteristics, he was a respected voice and a celebrated man, becoming an unquestionably Spanish artist. Fray Hortensio Félix Paravicino, preacher and poet of the 17th century d. C. Spanish, he wrote of him, in a well-known sonnet: "Crete gave him life, and the brushes / Toledo the best homeland, where he begins / to achieve eternities with death".

Artistic analysis

Pictorial style and technique

El Greco's training allowed him to achieve a conjunction between Mannerist design and Venetian color. However, in Italy the artists were divided: the Roman and Florentine mannerists defended drawing as essential in painting and extolled Michelangelo, considering color inferior, and denigrated Titian; the Venetians, on the other hand, pointed to Titian as the greatest, and attacked Michelangelo for his imperfect mastery of color. El Greco, as an artist trained in both schools, stayed in the middle, recognizing Titian as an artist of color and Michelangelo as a master of design. Even so, he did not hesitate to harshly discredit Michelangelo for his treatment of color. But scholars agree that it was a misleading criticism, since El Greco's aesthetics shared Michelangelo's ideals of the primacy of imagination over imitation in artistic creation. His fragmentary writings in various book margins indicate his adherence to Mannerist theories, and allow us to understand that his painting was not the result of spiritual visions or emotional reactions, but that he tried to create an artificial and anti-naturalistic art.

But his Venetian apprenticeship also had important consequences for his conception of art. Thus, the Venetian artists had developed a way of painting that was clearly different from the Roman mannerists: the richness and variety of color, the preponderance of naturalism over drawing, and the manipulation of pigment as an expressive resource. The Venetians, in contrast to the polished finish of the Romans, modeled the figures and objects with a sketchy technique, which achieved great depth and brilliance in the colors. El Greco's brushwork was also greatly influenced by the Venetian style, as Pacheco pointed out when visiting him in 1611: he touched up his paintings over and over again until he achieved an apparently spontaneous finish, as if from a sketch, which for him meant virtuosity. His paintings present a multitude of brushstrokes that did not blend into the surface, which observers at the time, such as Pacheco, called cruel smears . But he not only used the Venetian color palette and its rich, saturated hues; he also used the strident and arbitrary colors that the painters of the mannera liked, bright green yellows, orange reds and bluish grays. The admiration that he felt for the Venetian techniques was expressed in the following way in one of his writings: «I have the imitation of colors because of the greatest difficulty...». It has always been recognized that El Greco overcame this difficulty.

In the thirty-seven years that El Greco lived in Toledo, his style was profoundly transformed. He went from an Italianate style in 1577 to evolve in 1600 to a very dramatic, personal and original one, systematically intensifying the artificial and unreal elements: small heads resting on increasingly long bodies; the increasingly strong and strident light, bleaching the colors of the clothing, and a shallow space with an overpopulation of figures, which give the sensation of a flat surface. In his last fifteen years, El Greco took the abstraction of his style to unsuspected limits. His latest works have an extraordinary intensity, to the point that some scholars have sought religious reasons, assigning him the role of visionary and mystic. He managed to give his works a strong spiritual impact, reaching the objective of religious painting: to inspire emotion and also reflection. His dramatic and sometimes theatrical presentation of subjects and figures were vivid reminders of the glories of the Lord, the Virgin and her saints.

El Greco's art was a synthesis between Venice and Rome, between color and drawing, between naturalism and abstraction. He achieved his own style that implanted Venetian techniques in Mannerist style and thought.In his notes to Vitruvio he left a definition of his idea of painting:

The painting [...] is moderator of all that is seen, and if I could express with words what is the view of the painter, the view would seem like a strange thing as far as it concerns many faculties. But painting, being so universal, becomes speculative.

The question of the extent to which, in his profound transformation in Toledo, El Greco drew on his earlier experience as a Byzantine icon painter has been debated since the turn of the century XX d. Some art historians have argued that El Greco's transformation was steeped firmly in the Byzantine tradition and that his most individual characteristics derive directly from the art of his ancestors, while others have argued that Byzantine art cannot be related to the late work of El Greco. Álvarez Lopera points out that there is a certain consensus among specialists that in his mature work he occasionally used compositional and iconographic schemes from Byzantine painting.

For Brown, the role played by the painter's Toledo patrons is of great importance, learned men who knew how to admire his work, who were able to follow him and finance his foray into unexplored artistic spheres. Brown recalls that his last paintings, unconventional, he painted to adorn religious institutions run by these men. Finally, he points out that the adherence of these men to the ideals of the Counter-Reformation allowed El Greco to develop an enormously complex style of thought that served to represent religious themes with enormous clarity.

The historian of the XVIIth century d. C. Giulio Mancini expressed El Greco's belonging to the two schools, Mannerist and Venetian. He singled out El Greco among the artists in Rome who had begun an "orthodox revision" of Michelangelo's teachings, but he also noted the differences, stating that as a disciple of Titian he was sought after for his "resolute and fresh" style, as opposed to the static mode. that was then imposed in Rome.

The treatment of his figures is mannerist: in his evolution he not only lengthened the figures, but also made them more sinuous, looking for twisted and complex postures —the figura serpentinata. It was what Mannerist painters called the “fury” of the figure, and they considered that the undulating form of the flame of fire was the most appropriate to represent beauty. He himself considered elongated proportions more beautiful than life-size, according to his own writings.

Another characteristic of his art is the absence of still life. His treatment of pictorial space avoids the illusion of depth and landscape, he habitually developed his subjects in undefined spaces that appear isolated by a curtain of clouds. His large figures are concentrated in a small space close to the plane of the painting, often crowded together and superimposed.

The treatment given to birth is very different from usual. In his paintings the sun never shines, each character seems to have their own light inside or reflects light from an unseen source. In his last paintings, the light becomes stronger and brighter, to the point of bleaching the background of the colors. This use of light is consistent with his anti-naturalism and his increasingly abstract style.

Art historian Max Dvořák was the first to associate El Greco's style with mannerism and anti-naturalism. El Greco's style is currently characterized as "typically mannerist".

El Greco also excelled as a portrait painter, being able to depict the sitter's features and convey his character. His portraits are fewer in number than his religious paintings. Wethey says that "by simple means the artist created a memorable characterization that places him in the highest rank of portrait painters, alongside Titian and Rembrandt".

At the service of the Counter-Reformation

El Greco's patrons were mostly educated ecclesiastics and related to the official center of Spanish Catholicism, which was the Archdiocese of Toledo. El Greco's career coincided with the culminating moment of the Catholic reaffirmation against Protestantism, so the paintings commissioned by his patron followed the artistic guidelines of the Counter-Reformation. The Council of Trent, concluded in 1563, had reinforced the articles of faith. The bishops were responsible for ensuring compliance with orthodoxy, and the successive archbishops of Toledo imposed obedience to the reforms through the Council of the Archdiocese. This body, with which El Greco was closely related, had to approve all the artistic projects of the diocese that had to adhere faithfully to Catholic theology.

El Greco was at the service of the theses of the Counter-Reformation as is evident in his thematic repertoire: a large part of his work is dedicated to the representation of saints, whose role as intercessors of man before Christ was defended by the Church. He highlighted the value of confession and penance, which Protestants discussed, with multiple representations of penitent saints and also of Mary Magdalene. Another important part of her work extols the Virgin Mary, whose divine maternity was denied by Protestants and defended in Spain, given the great devotion she had in Spanish Catholicism.

Culture

Regarding El Greco's erudition, two inventories of his bookstore prepared by his son Jorge Manuel Teotocópuli have been preserved: the one made a few days after the painter's death and another, more detailed, made on the occasion of his marriage; He owned 130 copies (less than the five hundred that Rubens had, but more than the average painter of the time), a not inconsiderable amount that made his owner a philosopher and cosmopolitan painter and, despite the commonplace, less Neoplatonic than Aristotelian, since he owned three volumes of the Stagirite and none of Plato or Plotinus. Some of his books are carefully annotated, such as Vitruvius's Treatise on Architecture and Giorgio Vasari's famous Lives of the Greatest Italian Architects, Painters and Sculptors . Naturally, Greek culture dominates and has maintained a taste for contemporary Italian readings; not too extensive, after all, the religious books section (11 and unannotated); He considered painting a speculative science and had a particular fixation on architectural studies, which debunks the cliché that El Greco forgot perspective when he arrived in Spain: for every treatise on painting he had four on perspective.

The work of the workshop

In addition to the paintings by his own hand, there are a significant number of works produced in his workshop by assistants who, under his direction, followed his sketches. It is estimated that there are around three hundred canvases in the workshop, which are still accepted as autograph works in some studios. These works are made with the same materials, with the same procedures and following his models; the artist was partially involved in them, but most of the work was done by his assistants. Logically, this production does not have the same quality as his autograph works.Actually, he only had one notable disciple, Luis Tristán (Toledo, 1585- id . 1624).

The painter organized his production at different levels: the large commissions were carried out entirely by himself, while his assistants produced more modest canvases, with iconographies destined for popular devotion. The organization of the production, contemplating works totally autographed by the master, others with his partial intervention and a last group made entirely by his assistants, made it possible to work at various prices, since the market of the time could not always pay the high prices. teacher fees.

In 1585 he was selecting typologies and iconographies, forming a repertoire in which he worked repeatedly with an increasingly fluid and dynamic style. The popular success of his devotional paintings, highly sought after by his Toledo clientele for chapels and convents, led him to elaborate various themes. Some were especially interesting, repeating numerous versions of them: Saint Francis in ecstasy or stigmatized, the Magdalene, Saint Peter and Saint Paul, the Holy Face or the Crucifixion.

In Toledo there were thirteen Franciscan convents, perhaps for this reason one of the most popular subjects is San Francisco. About a hundred paintings on this saint came out of El Greco's workshop, of which 25 are recognized autographs, the rest are works in collaboration with the workshop or copies of the master. These dramatic and simple images, very similar, with only minor variations in the eyes or hands, were highly successful.

The theme of the repentant Magdalene, a symbol of the confession of sins and penance in the Counter-Reformation, was also in great demand. The painter developed at least five different typologies of this theme, the first based on Titian models and the last totally personal.

Customers from Toledo and other Spanish cities came to the workshop, attracted by the painter's inspiration. Between 1585 and 1600, numerous altar paintings and portraits left the workshop, destined for churches, convents and individuals. Some are of high quality, others are simpler works by his collaborators, although they are almost always signed by the master.

From 1585, El Greco supported his Italian assistant Francisco Proboste, who had worked with him since the Roman period. From 1600, the workshop occupied twenty-four rooms, a garden and a patio. In these early years of the century, the presence of his son and new assistant Jorge Manuel Theotocópuli, who was twenty years old at the time, became relevant in his workshop. His disciple Luis Tristán also worked in the workshop, as well as other collaborators.

Francisco Pacheco, a painter and father-in-law of Diego Velázquez, described the workshop he visited in 1611: he cited a large cabinet, filled with clay models made by El Greco and used in his work. He was surprised to see small-format oil copies of everything El Greco had painted in his life in a store.

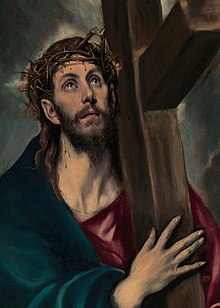

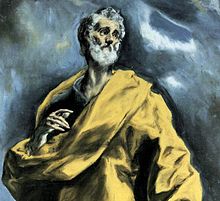

One of the most characteristic productions of the workshop in recent times are the cycles of the Apostles, represented as half or three-quarter busts with their corresponding symbols. Sometimes they were represented in pairs. They are ascetic figures, with lean and elongated silhouettes, reminiscent of Greek icons.

Sculpture and architecture

At that time in Spain the main way of decorating churches were altarpieces, which consisted of paintings, polychrome sculptures and an architectural structure of gilded wood. El Greco set up a workshop where all these tasks were carried out, and participated in the architectural design of various altarpieces. There is evidence of his studies on the architecture of the time, but his work as an architect is reduced to his participation in some altarpieces that he was commissioned to do.

Pacheco, in his visit to the workshop in 1611, cited the small plaster, clay and wax models made by El Greco and which he used to prepare his compositions. From the study of the contracts that El Greco signed, San Román concluded that he never made the carvings for the altarpieces, although in some cases he provided the sculptor with drawings and models for them. Wethey accepts as sculptures by El Greco The imposition of the chasuble on Saint Ildefonso that was part of the frame of El expolio and the Cristo resurrected that crowned the altarpiece of the Hospital de Tavera.

In 1945, the Count of the Infantas acquired the sculptures of Epimeteo and Pandora in Madrid and proved that they were the work of El Greco, since there are stylistic relationships with his pictorial and sculptural production. Xavier de Salas interpreted these figures as representations of Epimetheus and Pandora, seeing in them a reinterpretation of Michelangelo's David with slight variations: more elongated figures, a different position of the head and less open legs. Salas also pointed out that Pandora corresponds to an inversion of the figure of Epimetheus, a characteristic aspect of mannerism. Puppi considered that they were models to determine the most accurate position of the figures on the right of the Laocoon painting.

Historical recognition of his painting

El Greco's art has been appreciated in very different ways throughout history. Depending on the period, he has been designated as a mystic, mannerist, proto-expressionist, protomodern, lunatic, astigmatic, quintessential Spanish spirit and Greek painter.

The few contemporaries who wrote about El Greco admitted his technical mastery, but were baffled by his singular style. Francisco Pacheco, a painter and theoretician who visited him, could not admit El Greco's disdain for drawing and for Michelangelo, but he did not exclude him from the great painters. Towards the end of the XVIIth century d. C. this ambiguous assessment turned negative: the painter Jusepe Martínez, who knew the works of the best Spanish and Italian Baroque painters, considered his capricious and extravagant style; for Antonio Palomino, author of the main treatise on Spanish painters until it was superseded in 1800, El Greco was a good painter in early works when he imitated Titian, but in his late style "he tried to change his manner, with such extravagance, that He came to make his painting despicable and ridiculous, as well in the disjointedness of the drawing as in the blandness of the color». Palomino coined a phrase that remained popular well into the 19th century d. C.: «What he did well, no one did better; and what he did wrong, no one did worse. Outside of Spain there was no opinion about El Greco because all his work was in Spain.

The poet and critic Théophile Gautier, in his book about his famous trip to Spain in 1840, formulated his important review of the value of El Greco's art. He accepted the general opinion of extravagant and a little crazy, but giving it a positive connotation, and not pejorative as before. In the 1860s Eugène Delacroix and Jean-François Millet already possessed authentic works by El Greco. Édouard Manet traveled to Toledo in 1865 to study the work of the Greek painter, and although he returned deeply impressed by the work of Diego Velázquez, he also praised the Cretan painter. Paul Lefort, in his influential 1869 history of painting, wrote: "El Greco was not the madman or the outrageous extravagant he was thought to be. He was a bold and enthusiastic colourist, probably too given to strange juxtapositions and unusual tones that, adding daring, he finally succeeded first in subduing and then in sacrificing everything in his quest for effect. Despite his mistakes, El Greco can only be considered as a great painter ». For Jonathan Brown, Lefort's opinion opened the way for the consideration of El Greco's style as the work of a genius, not that of a lunatic who only went through intervals of lucidity.

In 1907 Manuel Bartolomé Cossío published a book about him that marked an important advance in the knowledge of the painter. He compiled and interpreted everything published up to then, released new documents, made the first outline of the painter's stylistic evolution, distinguishing two Italian and three Spanish periods, and produced the first catalog of his works, which included 383 paintings.. He showed a Byzantine painter, trained in Italy, but Cossío was not impartial when he thought that El Greco had assimilated Castilian culture during his stay in Spain, affirming that he was the one who reflected it most deeply. Cossío, mediated by the nationalist ideas of Spanish regenerationism at the beginning of the XX century d. C., showed a Greco imbued and influenced by the Castilian soul. Cossío's book acquired great prestige, for decades it has been the reference book, and is the cause of El Greco's general consideration as an interpreter of Spanish mysticism.

San Román published El Greco in Toledo in 1910, revealing 88 new documents, among them the inventory of assets at the death of the painter, as well as other very important documents on the main works. San Román established the documentary knowledge base of the Spanish period.

El Greco's fame began at the beginning of the XX century AD. C. with the first recognitions from European and American organizations, as well as from the artistic avant-garde. The idea of El Greco as a precursor of modern art was especially developed by the German critic Meier-Graefe in his book Spanische Reise, where, analyzing the work of the Cretan, he considered that there were similarities with Paul Cézanne, Manet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Edgar Degas, and he also believed that he saw in the work of El Greco that all the inventions of modern art were anticipated. the work of the Polish painter Władysław Jahl, who was part of the ultraist vanguard in Madrid; Salvador Viniegra, Azorín and Pío Baroja dedicated several articles to him and the latter dedicated several passages to him in his novel Camino de perfección (pasión mística) (1902), as well as other prominent authors of the generation of '98.

The Portuguese doctor Ricardo Jorge pointed out the hypothesis of madness in 1912, because he thought he saw in El Greco a paranoid person; while the German Goldschmitt and the Spanish Beritens defended the hypothesis of astigmatism to justify the anomalies in their painting.

About 1930 the painter's stay in Spain was already known in documents and the study of the stylistic evolution of the Toledo period began, however little was known about the previous periods.

Between 1920 and 1940, the Venetian and Roman periods were studied. The discovery of the signed Triptych of Modena showed the transformation of the Cretan style into the language of the Venetian Renaissance, and during the Second World War a multitude of Italian paintings were erroneously assigned to it, with up to 800 paintings being considered in its catalog Gregorio Marañón dedicated his last book to him, El Greco y Toledo (1956).

In 1962 Harold E. Wethey lowered this figure considerably, and established a convincing corpus that amounted to 285 authentic works. The value of Wethey's catalog is confirmed by the fact that in recent years only a small number of paintings have been added to or removed from its list.

The extensive comments on art written by the painter himself, recently discovered and made known by Fernando Marías Franco and Agustín Bustamante, have contributed to demonstrating that the painter was an intellectual artist immersed in the artistic theory and practice of the century XVI Italian.

El Greco in literature

The influence of the figure and the work of El Greco in Spanish and universal literature is undoubtedly formidable. The very long chapter that Rafael Alarcón Sierra dedicates to the study of this influence in the first volume of Hispanic literary themes (Zaragoza: Universidad de Zaragoza, 2013, pp. 111-142) does not even exhaust the subject. If Goya is discovered by the romantics and Velázquez is considered a master by the painters of naturalism and impressionism, El Greco is seen as "a precedent for symbolists, modernists, cubists, futurists or expressionists, and as happens with the previous ones, an inexhaustible source of inspiration and study [...] in plastic arts, literature and art history, where a new category was created to explain his anti-classical and anti-naturalist work: mannerism».

In the XVI century, the praise paid by poets such as Hortensio Félix Paravicino, Luis de Góngora, Cristóbal de Mesa, José Delitala and Castelvi; in the 17th century, those of the poets Giambattista Marino and Manuel de Faria y Sousa, as well as those of the chroniclers Fray José de Sigüenza and Fray Juan de Santa María and those of the painting writers Francisco Pacheco and Jusepe Martínez; in the 18th century, those of the critics Antonio Palomino, Antonio Ponz, Gregorio Mayáns y Siscar and Juan Agustín Ceán Bermúdez and, in the XIX century, Eugenio Llaguno. When the Spanish Gallery opened in the Louvre in 1838 there were nine works by El Greco, and Eugène Delacroix owned a copy of Expolio. Jean-François Millet purchased a Santo Domingo and a San Ildefonso. Charles Baudelaire admired Lady with an Ermine (which Théophile Gautier compared to La Gioconda and today some consider to be by Sofonisba Anguissola); Champfleury thought of writing a work on the painter and Gautier praised his paintings in his Voyage en Espagne , where he declared that in his works reigns “a depraved energy, a sick power, which betrays the great painter and to the crazy genius». In England, William Stirling-Maxwell vindicated the early days of El Greco in his Annals of the Artists of Spain, 1848, III vols. There are innumerable foreign travelers who stop before his works and comment on them, while the Spanish, in general, forget him or repeat the eighteenth-century clichés about the author, and although Larra or Bécquer mention him in passing, it is with great incomprehension, although the latter had projected a writing, "The madness of genius", which was going to be an essay on the painter, according to his friend Rodríguez Correa. The historical novelist Ramón López Soler does appreciate it in the prologue to his novel Los bandos de Castilla. But critics such as Pedro de Madrazo began to reassess his work in 1880 as a very important precedent of the so-called Spanish School, although until 1910 he still appears attached to the Venetian School and until 1920 he did not have his own room. In France, Paul Lefort (1869) includes him in the Spanish School and he is one of the idols of Edouard Manet's circle (Zacharie Astruc, Millet, Degas). Paul Cézanne made a copy of The Lady with the Ermine and Toulouse Lautrec will paint his Portrait of Romain Coolus in the manner of El Greco. And the German Carl Justi (1888) also considers it one of the precedents of the Spanish School. The American painter John Singer Sargent owned one of the versions of Saint Martin and the Beggar. The decadent writers make El Greco one of their fetishes. The protagonist of Against the grain (1884) by Huysmans decorates his bedroom exclusively with paintings by El Greco. Théodore de Wyzewa, symbolism theorist, considers El Greco a painter of dream images, the most original of the XVI century (1891). Subsequently, the decadentist Jean Lorrain followed that inspiration when describing it in his novel Monsieur de Bougrelon (1897).

The European and Spanish exhibitions follow one another from the London one of 1901 (Exhibition of Spanish art in the Guildhall) to the tercentenary of 1914: Madrid, 1902; Paris, 1908; Madrid, 1910; Cologne, 1912. In 1906 the French magazine Les Arts dedicated a monographic issue to him. The II Marquis de Vega-Inclán inaugurated the El Greco House-Museum in Toledo in 1910. Its price is already so high that it leads to the sale of several El Grecos from private Spanish collections that end up abroad. At the beginning of the 20th century, the Catalan modernist painters fully recovered it: Santiago Rusiñol (who transferred his enthusiasm to the Belgian symbolists Émile Verhaeren and Théo van Rysselberghe), Raimon Casellas, Miquel Utrillo, Ramón Casas, Ramón Pichot or Aleix Clapés, as well as other artists. close friends, such as Ignacio Zuloaga (who spread his enthusiasm for the Cretan to Maurice Barrès, who wrote Greco or the secret of Toledo), and to Rainer María Rilke, who dedicated a poem to his Asunción in Ronda, 1913) and Darío de Regoyos. The nocturnal visit between candles that Zuloaga makes to the Burial of the Lord of Orgaz is recorded in chapter XXVIII of Camino de perfección (pasión mística), by Pío Baroja, and also has words for the painter Azorín in La voluntad and in other works and articles. Picasso takes into account the Vision of the Apocalypse in his Les demoiselles d'Avignon. Interest in the candidate also reaches Julio Romero de Torres, José Gutiérrez Solana, Isidro Nonell, Joaquín Sorolla and many more. Emilia Pardo Bazán will write a "Letter to El Greco" in La Vanguardia. The writers of the Institución Libre de Enseñanza spread their admiration for El Greco, especially Francisco Giner de los Ríos and Manuel Bartolomé Cossío, the latter for his El Greco (1908). The presence of El Greco in the Toledo portrayed by Benito Pérez Galdós in his novel Ángel Guerra is important and the comparison of his characters with portraits of El Greco is frequent in his novels. So also Aureliano de Beruete, Jacinto Octavio Picón, Martín Rico, Francisco Alcántara or Francisco Navarro Ledesma. Eugenio d'Ors dedicates space to El Greco in his famous book Three hours in the Prado Museum and in Poussin and El Greco (1922). Amado Nervo writes one of his best stories, inspired by one of his paintings, A dream (1907). Julius Meier-Graefe dedicates Spanische Reise (1910) to him and August L. Mayer El Greco (1911). Somerset Maugham describes him with admiration through the main character and the 88th chapter of his novel Human Servitude, 1915; in his essay Don Fernando, 1935, he tempers his admiration and divines an alleged homosexuality as the origin of his art, as Ernest Hemingway does in chapter XVII of Death in the Afternoon > (1932) and Jean Cocteau in his Le Greco (1943).

Kandinsky, Franz Marc (who produced under his influence Agony in the Garden), considered him a proto-expressionist. As Romero Tobar declares, the late production of the Cretan painter impressed August Macke, Paul Klee, Max Oppenheimer, Egon Schiele, Oskar Kokoschka, Ludwig Meidner, Jacob Steinhardt, Kees van Dongen, Adriaan Korteveg and Max Beckmann. Hugo Kehrer dedicated his Die Kunst des Greco (1914) to him and finally the Austrian art historian Max Dvorak defined him as the highest representative of the aesthetic category of Mannerism. Ramón María del Valle-Inclán, after a Buenos Aires conference in 1910, dedicated the chapter "Aesthetic quietism" of his The Wonderful Lamp. Miguel de Unamuno dedicates several poems to the candiota from his Cancionero and dedicates an impassioned article to him in 1914. Juan Ramón Jiménez dedicates several aphorisms to him. The critic "Juan de la Encina" (1920) opposes José de Ribera and El Greco as "the two extremes of the character of Spanish art": strength and spirituality, the petrified flame and the living flame, which he completes with the name of Goya. In that same year, 1920, his popularity led to the premiere of the Swedish ballet by Jean Börlin in Paris El Greco, with music by Désiré-Émile Inghelbrecht and scenery by Moveau; Also in that year, Félix Urabayen published his novel Toledo: piedad, where he dedicated a chapter in which he speculated on his possible Jewish origin, a theory put forward by Barrès and that Ramón Gómez de la Serna would take up again — El Greco (the visionary of painting)— and Gregorio Marañón (Elogio y nostalgia de Toledo, only in the 2nd ed. of 1951, and El Greco and Toledo , 1956, where he also maintains that he was inspired by the lunatics of the famous Toledo Asylum for his Apostles), among others. And in the first chapters of Don Amor vuelvo a Toledo (1936) he criticizes the sale of the Illescas frets and the theft of some of his paintings from Santo Domingo el Antiguo. Luis Fernández Ardavín recreates the story of one of his portraits in his most famous drama in verse, La dama del ermiño (1921), later made into a film by his brother Eusebio Fernández Ardavín in 1947. Jean Cassou writes Le Greco (1931). Juan de la Encina prints his El Greco in 1944. In exile, Arturo Serrano Plaja, after having protected some of his paintings during the war, writes his El Greco (1945). And Miguel Hernández, Valbuena Prat, Juan Alberto de los Cármenes, Enrique Lafuente Ferrari, Ramón Gaya, Camón Aznar, José García Nieto, Luis Felipe Vivanco, Rafael Alberti, Luis Cernuda, Concha Zardoya, Fina de Calderón, Carlos Murciano also write about him., León Felipe, Manuel Manrique de Lara, Blanca Andreu, Hilario Barrero, Pablo García Baena, Diego Jesús Jiménez, José Luis Puerto, Louis Bourne, Luis Javier Moreno, José Luis Rey, Jorge del Arco, José Ángel Valente... Seven Sonnets to El Greco by Ezequiel González Mas (1944), the Lyrical Conjugation of El Greco (1958) by Juan Antonio Villacañas and The Burial of the Count of Orgaz (2000) by Félix del Valle Díaz. In addition, Jesús Fernández Santos won the Ateneo de Sevilla prize with his historical novel El Griego (1985).

Outside Spain, and apart from those already mentioned, Ezra Pound quotes El Greco in his Art Notes and Francis Scott Fitzgerald at the end of his The Great Gatsby (1925). Paul Claudel, Paul Morand, Aldous Huxley took care of the candiot, and the German Stefan Andres dedicates his novel El Greco paints the Grand Inquisitor to him, in which Cardinal Fernando Niño de Guevara appears as a metaphor for the Nazi oppression. An aficionado of El Greco is one of the characters in L'Espoir (1938), by André Malraux, and another character is in charge of protecting the Grecos from Toledo in Madrid. In one of the essays in his The Voices of Silence (1951), reviewed by Alejo Carpentier, Malraux plays the painter. The aforementioned Ernest Hemingway considered View of Toledo the best painting in the entire Metropolitan Museum in New York and dedicated a passage to it in For Whom the Bell Tolls. Nikos Kazantzakis, Donald Braider, Jean-Louis Schefer...

Pictorial work

Part of his best work is included to give an overview of his pictorial style, his artistic evolution and the circumstances that have involved his works both in their execution and in subsequent vicissitudes. He was a painter of altarpieces, which is why we begin with the altarpiece of Santo Domingo , the first one he conceived. El expolio , one of his masterpieces, shows his first style in Spain still influenced by his Italian masters. The Burial of the Count of Orgaz is the landmark work of his second period in Spain, the so-called maturity. El retablo de doña María marks the start of his latest style, a radical turn for which he is universally admired. Illescas's painting explains how his late style was stylized. Two of the renowned portraits of him are then included. It ends with the Vision of the Apocalypse , which shows the extreme expressionism of his latest compositions.

The main altarpiece of Santo Domingo el Antiguo

In 1576, in Santo Domingo el Antiguo, a new church was built with the assets of the deceased Doña María de Silva, destined to be her burial place.

El Greco had just arrived in Spain and during his stay in Rome he had met the brother of the testamentary executor builder of Santo Domingo, Luis de Castilla. It was the brother who contacted El Greco and who spoke favorably of the quality of the painter.

There were nine canvases in total, seven on the main altarpiece and another two on two side altars. Currently, only three original paintings remain in the altarpiece. The others have been sold and replaced by copies.

Until then, El Greco had faced such an ambitious task, he had to conceive large-scale paintings, fit each of the respective compositions and harmonize them all as a whole. The result was widely recognized and brought him immediate fame.

In the main canvas, The Assumption, he established a pyramidal composition between the two groups of apostles and the Virgin; for this he needed to highlight it and diminish the importance of the angels. There is a tendency to horror vacui: include the maximum number of figures and the minimum environmental elements. Gestures and attitudes stand out. This aspect was always one of his great concerns, to provide his figures with eloquence and expression. He achieved it by incorporating and constituting throughout his career a repertoire of gestures whose expressiveness he should know well.

The looting

The chapter of the cathedral of Toledo must have commissioned El Greco El expolio on July 2, 1577. It was one of the first works in Toledo, together with the paintings on the altarpiece of Santo Domingo el Antiguo, recently arrived from Italy. The reason for this painting is the initial moment of the Passion in which Jesus is stripped of his clothes. The painter was inspired by a text by Saint Buenaventura, but the composition he devised did not satisfy the council. In the lower left part he painted the Virgin, Mary Magdalene and María Cleofás, although it is not recorded in the gospels that they were there, while in the upper part, above the head of Christ, he placed a large part of the group that escorted him, drawing inspiration from ancient Byzantine iconography. The council considered that both aspects were "improperties that darkened history and devalued Christ". This was the reason for the first lawsuit that the painter had in Spain. The appraisers appointed by El Greco requested 900 ducats, an excessive amount.The painter ended up receiving 350 ducats as payment, but he did not have to change the figures that had generated the conflict.

Cossío made the following analysis of this painting in his famous book on the painter:

- The artist was to represent Christ not as God, but as an innocent man and victim of human passions. He concentrated all the main and secondary elements, scattered in his previous paintings, in a single action around the protagonist. He surrounded it from a tight group of hard and shady heads, each with their own personality. He introduced two different episodes at his feet, closing the scene below. It is the man who prepares the cross and, opposite, the three Marys who observe it with sadness.

- "The unity of composition is so perfect that all interest is absorbed by the figure of Christ." The teacher knew how to create this effect, establishing a circle composition around Jesus.

- All that is not the protagonist is darkened and reduced, while Christ is illuminated and stands out. Thus the illuminated face of Christ and his red robe form a very strong contrast with the dark faces of the companions and with the gray intonation that dominates the painting.

El Greco and his workshop painted several versions of this same theme, with variations. Wethey cataloged fifteen paintings with this theme and four other half-length prints. In only five of these works did he see the artist's hand and the other ten he considered to be productions of the workshop or later copies of small size and poor quality.

The burial of the Count of Orgaz

The church of Santo Tomé housed the remains of the lord of Orgaz, who had died in 1323 after a very generous life in donations to religious institutions in Toledo. According to a local legend, the charity of the Lord of Orgaz had been rewarded at the time of his burial, miraculously appearing Saint Stephen and Saint Augustine who introduced his corpse into the tomb.

The contract for the painting, signed in March 1586, included a description of the elements that the artist had to represent: «At the bottom... a procession has to be painted of how the priest and the others clergymen who were doing the offices to bury Don Gonzalo de Ruiz de Toledo, Lord of the town of Orgaz, and Saint Augustine and Saint Stephen came down to bury the body of this gentleman, one holding his head and the other his feet throwing him in the grave and pretending around many people who were watching and above all this an open sky of glory has to be made...».

The altarpiece of Doña María de Aragón

In 1596 El Greco was commissioned for the altarpiece of the church of the Encarnación seminary school in Madrid, better known by the name of his patron, Doña María de Aragón. It was to be carried out in three years and was valued at more than sixty-three thousand reais, the highest price he received in his life. The college was closed in 1808 or 1809, as separate decrees by José Bonaparte reduced the existing convents and later suppressed the religious orders. The building was transformed into a courtroom in 1814, currently the Spanish Senate, and the altarpiece was dismantled during that period. After several transfers (in one of them he was in the house of the Inquisition) he ended up in the Museo de la Trinidad, created with works of art requisitioned by the Confiscation Law. Said museum merged with the Museo del Prado in 1872 and for this reason five of his canvases are in it. During these transfers, the sixth canvas, The Adoration of the Shepherds, was sold and is currently in the National Museum of Romanian Art in Bucharest.

The lack of documents on it has given rise to different hypotheses about the cadres that make it up. In 1908 Cossío related The Baptism, The Crucifixion, The Resurrection and The Annunciation. August L. Mayer proposed in 1931 the relationship between the previous canvases with The Pentecost and The Adoration of the Shepherds of Bucharest. In 1943 Manuel Gómez Moreno proposed a reticular altarpiece made up of these six paintings without arguing for it. But for some specialists The Resurrection and The Pentecost would not be part of it as they corresponded to different stylistic formulations.

In 1985, a document from 1814 appeared with a record of the works deposited in the house of the Inquisition that mentions "seven original paintings by Domenico Greco that were on the High Altar". This information has strengthened Gómez Moreno's hypothesis of an altarpiece with three streets on two floors, assuming that the seventh would be on a third floor as an attic.

- Possible composition of the altarpiece of Mary of Aragon

The themes, except The Pentecost, had already been developed before, some in its Italian stage. According to Ruiz Gómez, these themes are taken up with great originality, showing his most expressionist spirituality. From this moment on, his work takes a very personal and disconcerting path, distancing himself from the naturalistic style that he began to dominate at that time. The scenes are set in claustrophobic spaces, enhancing the verticality of the formats. A spectral light highlights the unreality of the figures, some in very marked foreshortenings. The cold, intense and contrasting color applied with ease to his powerful anatomical builds shows what would be his late style.

Main Chapel of the Hospital de la Caridad de Illescas

In 1603 he was commissioned to carry out all the decorative elements of the main chapel of the church of the Hospital de la Caridad de Illescas, which included altarpieces, sculptures and four paintings. El Greco developed an iconographic program that praised the Virgin Mary. The four paintings have a similar pictorial style, three of them circular or elliptical in format.

The Annunciation seen on the right is circular in format and is a reworking of the one he painted for the Colegio de Doña María de Aragón. Even maintaining the previous types and gestures of the Colegio de María de Aragón, the painter advances in his late expressionism, his figures are more flaming and agitated with a more disturbing inner force.

Portraits

From his beginnings in Italy, El Greco was a great portrait painter. The composition and style are learned from Titian, the placement of the figure, normally half-length, and the neutral backgrounds. The best portraits of him, already in his maturity in Toledo, follow these criteria.

The gentleman with his hand on his chest is one of the most important of the artist and symbol of the Spanish knight of the Renaissance. The rich sword, the hand on the chest carried with a solemn gesture and the relationship that the knight establishes with the viewer looking into his eyes, turned this portrait into a reference for what is considered to be the essence of what is Spanish, of the honor of Castile.

This is an early work by El Greco, who had recently arrived in Spain, since his workmanship is close to the Venetian manners. The canvas has been restored on different occasions, in which color faults were retouched, the background was repainted and the character's clothing had been retouched. The restoration of 1996 has been very controversial because by removing the repainting of the background and those of the clothing, it changed the vision that this character has been projected for a long time.

Of the Portrait of an Elderly Gentleman the identity of the character is unknown and its high pictorial quality and psychological penetration stand out. For Ruiz Gómez, his honey-colored eyes and kind expression, somewhat lost, stand out. in his lean face, with his long, thin nose turned slightly to the right and his thin lips, graying mustache and goatee. A kind of aura separates the head from the background, blurring the outline and giving it movement and vivacity. Álvarez Lopera highlighted the accentuation of the traditional asymmetries of El Greco's portraits and described the sinuous line that orders this face from the central lock passing through the nose and ending at the tip of the chin. Finaldi he sees in the asymmetry a double emotional perception, slightly smiling and vivacious on the right side, concentrated and thoughtful on the left.

The vision of the Apocalypse

This canvas was commissioned from him in 1608, it is one of his last works and shows his most extreme style. At the painter's death in 1614, it had not yet been delivered. The painting was to be placed in an altarpiece in the chapel of the Hospital de Tavera in Toledo. In the restoration of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 1958, after its purchase, it was found that it had not only been cut at the top where the edge was frayed but also on its left side. According to Álvarez Lopera, it did have the same measurements as the painting on the other side altarpiece, The Annunciation, 406 x 209 cm, the part cut at the end of the century XIX d. C. would be the upper one 185 cm high and the left cut 16 cm wide, the original proportions being approximately twice as high as wide.

It represents the moment of the Apocalypse, when God shows Saint John in a vision the opening of the seven seals: «When he opened the fifth seal, I saw under the altar the souls of those slaughtered for the word of God and for the testimony they gave. And they cried out with a loud voice saying: “How long, Lord, holy and true, will you not do justice, and will you not avenge our blood on those who live on earth?” And each of them was given a white robe and they were told to rest a while longer..." (Revelation 6, 9-11).

The painting, in its current state after the cut, is dominated by the gigantic figure of Saint John. The resurrected are seven, the magic number of the Apocalypse, the same number that Dürer and other authors used when representing this same passage.

For Wethey, color has great relevance in this painting. The luminous blue of Saint John's dress where white lights are reflected and, as a contrast, at his feet is a pink cloak. On the left, the naked martyrs have a background with a pale yellow cloak, while the bodies of the women are of a great whiteness that contrasts with the yellowish male bodies. Green cloaks with yellow reflections are the background of the three nudes on the left. The martyrs form an irregular group in an indefinite pale blue space on a reddish ground and all in an environment of dark clouds that produces a dreamy impression.

It is not known about Del Greco the personal religious meaning of his work or the reason for his ultimate evolution towards this anti-naturalist and spiritualist painting, where as in this Vision of the Apocalypse, he systematically violated all the laws established in Renaissance rationalism. Wethey considered that this late mode of expression of El Greco was related to the early mannerism. Dvorak, the first to firmly associate the anti-naturalism of the Cretan with Mannerism, considered that this anti-naturalism, in the same way that happened to Michelangelo or Tintoretto in their final works, was a consequence of the world in crisis that emerged from the collapse of Renaissance optimism and his faith in reason.

At the movies

- The movie El Grecofrom 1966, led by Luciano Salce.

- The movie El Greco2007, led by Yannis Smaragdis.

Contenido relacionado

Pamplona

Barcelona County

Stone Age