Eiffel Tower

The Eiffel Tower (Tour Eiffel, in French), initially called the Tour de 300 mètres (300-meter tower ) is a puddled iron structure initially designed by the civil engineers Maurice Koechlin and Émile Nouguier and built, after an aesthetic redesign by Stephen Sauvestre, by the French civil engineer Gustave Eiffel and his collaborators for the Universal Exposition of 1889 in Paris.

Located at the end of the Champ de Mars on the banks of the River Seine, this Parisian monument, a symbol of France and its capital, is the tallest structure in the city and the most visited ticket-taking monument in the world, with 7.1 million tourists each year. With a height of 300 meters, later extended with an antenna to 324 meters, the Eiffel Tower was the tallest structure in the world for 41 years.

It was built in two years, two months and five days, and at the time it generated some controversy among the artists of the time, who saw it as an iron monster. After finishing its function as part of the Universal Exhibitions of 1889 and 1900, it was used in tests by the French army with communication antennas, and today it serves, in addition to being a tourist attraction, as a radio and television program station. On March 15, 2022, the radio antenna was replaced with the help of a helicopter, going from 324 to 330 m in total height.

General characteristics

Initially the subject of controversy for some, the Eiffel Tower served as the introduction to the World's Fair in Paris in 1889, and has welcomed more than 250 million visitors since it opened. Its exceptional size and immediately recognizable silhouette made the tower an emblem of Paris.

Conceived in the imagination of Maurice Koechlin and Émile Nouguier, head of the study office and head of the methods office, respectively, of the Eiffel & Co, was intended to be the "nail (center of attention) of the 1889 exhibition to be held in Paris", which would also commemorate the centenary of the French Revolution. The first plan for the tower was made in June 1884. Stephen Sauvestre, the main architect of the company's projects, was commissioned to improve its aesthetics.

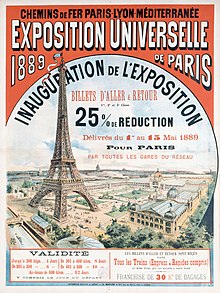

On May 1, 1886, the Minister of Trade and Industry, Édouard Lockroy, an enthusiastic supporter of the project, signed a decree declaring open "a support for the Universal Exposition of 1889." Gustave Eiffel won this economic support and signed an agreement on January 8, 1887 that set the modalities for the construction of the building.

Built in two years, two months and five days (from 1887 to 1889) by 250 workers, it was officially inaugurated on March 31, 1889. Resisting the continuous effect of corrosion on its metal structure, the Eiffel Tower did not It will truly experience massive and constant success until the 1960s, with the development of international tourism. Now it welcomes more than six million visitors each year.

Its 300 meters high allowed it to carry the title of "the tallest structure in the world" until the construction in 1930 of the Chrysler Building, in New York. Built on the Champ de Mars near the Seine River, in the 7th arrondissement of Paris, it is currently managed by the Society for the Administration of the Eiffel Tower (Société d'exploitation de la tour Eiffel, SETE). The place, which employs 500 people (250 direct employees of SETE and 250 of the different concessionaires installed on the monument), is open every day of the year.

Technical data

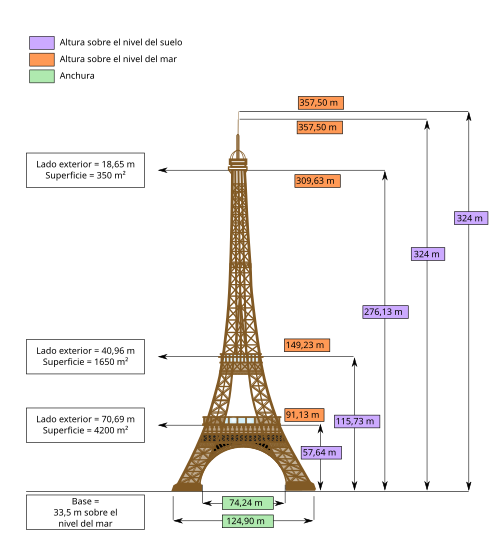

Main dimensions of the Eiffel Tower:

- Citations

- Altitude of the base (on sea level): 33.5 meters

- Length of the internal divergence between the two pillars: 74,24 meters

- Longitude of the external divergence between the two pillars: 124.9 meters

- 1.a plant

- Height of the first floor on the basis: 57,63 meters

- Altitude of the first floor on sea level: 91.13 meters

- Outside side (to the level of the plant): 70,69 meters

- Area (to the level of the plant): 4200 m2

- 2.a plant

- Height of the second floor on the basis: 115.73 m

- Altitude of the second floor on the sea level: 149,23 m

- External side (to the level of the plant): 40,96 m

- Area (to the level of the plant): 1650 m2

- 3.a plant

- Height of the third floor on the basis: 276,13 m

- Altitude of the third floor on sea level: 309,63 m

- External side (to the level of the plant): 18,65 m

- Area (to the level of the plant): 350 m2

- Total heights

- Total height with antenna in the year 2022: 330 m

- Total height with antenna in 2000: 324 m

- Total height with antenna in 1994: 318,7 m

- Total height with antenna in 1991: 317,96 m

- Total height with antenna in 1989: 312,27 m

- Total height without flag in 1889: 300 m

Description of the tower by levels

The following information describes the main technical data of each floor:

The Foundation

| Position | Dimensions | Construction | Designers | Materials |

| Tower feet | Length: 25 m Height: 4 m | 1887 | Maurice Koechlin Émile Nouguier Stephen Sauvestre | Hormigon Grava Steel |

The tower sits in a square 125 meters on each side, according to the same terms of the 1886 competition. It is 325 meters high with its 116 antennas; the base is located 33.5 meters above sea level.

The foundations: the two pillars located on the side of the Military School of France rest on a 2-meter layer of concrete; This, in turn, rests on a bed of gravel, forming an excavation seven meters deep. The foundation bases of the two pillars on the Seine River side are even below the river level.

Workers worked in pressurized metal foundation pits into which compressed air was injected (using the so-called Triger method). 16 solid foundations support each of the edges of the four pillars and huge 78 dm long fastening bolts fix the cast steel hull on which each pillar rests.

The Pillars: Currently, the ticket booths occupy the north and west pillars; the lifts are accessible (except for any repair or maintenance operations) from the north, east and west pillars. The stairs (open to the public up to the second floor, totaling 1,665 steps to the top) are accessible from the south pillar, which also houses a private elevator, reserved for staff and guests of the gastronomic restaurant Le Jules Verne, located on the second floor, and a freight elevator.

The arches: stretched between each of the four pillars, they rise 39 meters above the ground and have a diameter of 74 meters. Although highly decorated in Stephen Sauvestre's initial sketches, they were considerably simplified later. Their function is purely aesthetic, and they do not contribute to the structural behavior of the tower.

The first level

| Position | Dimensions | Surface | Construction | Materials | |

| 57.63 m from the ground | Long: 70.69 m | 4200 m2 | 1887 | Iron Iron Iron | |

Situated 57 meters above the ground, with an area of 4,200 square meters, it can support the simultaneous presence of approximately 3,000 people.

The 2.6 m wide perimeter gallery surrounding the first floor offers a 360° view over Paris. This gallery has several orientation maps and spyglasses that allow you to observe the Parisian monuments. Pointing outwards, the names of seventy-two personalities from the scientific world of the 18th and 19th centuries are inscribed. (See: 72 wise men from the Eiffel Tower)

This first floor houses the restaurant 58 Tour Eiffel which spans more than two levels. This place offers on one side a panoramic view over Paris, and on the other a view into the tower. Its name comes from the height of the first floor of the Eiffel Tower, located 58 m above street level. Until the 2008 reform, it was called Altitude 95. It shares the first floor with the Gustave Eiffel Room, a meeting place (with a capacity of 130 people as a restaurant, 200 as a conference room and 300 for cocktails).

You can also see some relics related to the history of the Eiffel Tower, including a section of the spiral staircase that, at the beginning of the monument's construction, climbed to the top. This staircase was dismantled in 1986, during a major renovation work on the tower. It was then cut into 22 sections, of which 21 were sold at auction, and mostly purchased by American collectors.

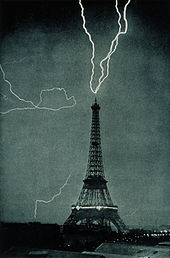

Finally, a follow-up of the movements of the summit makes it possible to describe the oscillations of the tower under the effect of wind and thermal expansion. Gustave Eiffel had required that it be able to withstand a 7 dm range of oscillation, which was never the case, although in fact, during a heat wave in 1976, the oscillation amplitude was 18 cm, plus 13 cm during a storm in December 1999 (whose winds were 240 km/h). In 1982 the original metal frame was reinforced with composite materials to minimize this problem. One of the peculiarities of the tower is that it "runs away from the sun". Indeed, the heat (and therefore, the expansion of the iron) being more important on the sunny side, causes the summit to move slightly in the opposite direction.

The second level

| Position | Dimensions | Surface | Construction | Materials | |

| 115.73 m from the ground | Long: 40,96 m | 1650 m2 | 1888 | Iron Iron Iron | |

Situated 115 meters above the ground, it has an area of approximately 1650 square meters; It can support the simultaneous presence of around 1600 people.

It is considered to be the floor with the best view, due to the fact that the altitude is optimal in relation to the buildings below (they are less visible on the third floor) and the general perspective (obviously more limited on the third floor). first floor). When the weather allows it, it is estimated that it is possible to see up to 55 km to the south, 60 to the north, 65 to the east and 70 to the west. Glass windows were installed throughout the floor to allow a very wide view from above. Metal protection fences are also installed to prevent any attempt to jump into the void, be it a suicide or a sporting challenge.

It houses the restaurant Le Jules Verne, a renowned gastronomic venue that has a large window that allows an excellent view of Paris. A "private" elevator (it also serves the tower's maintenance staff), located in the southern pillar, leads directly to a 500 m² platform, exactly 123 meters high. Normally, because the restaurant's clientele comes from distant places, the cutlery is reserved in advance.

The intermediate level

Halfway between the second level and the third level there is an intermediate platform at elevation 195 (80 m equidistant from the other two levels), which is currently not accessible to tourists. From 1889 (opening date of the tower) until 1983 (when the original elevator was replaced) it served to house the hydraulic machinery of the "Edoux" elevator, and to transfer visitors between its two cabins. Since it was not possible to overcome the 160.40 m difference in level between the second and third floors with a single hydraulic mechanism, a system with two cabins that worked in the opposite direction was installed, carrying out the ascent in two phases. The upper cabin (driven by the aforementioned hydraulic mechanism) made the journey between the intermediate platform and the third level; while the lower cabin (which served as a counterweight), moved between the intermediate platform and the second level. When the upper cabin reached the third level, the lower one reached the second; and when the march was reversed, they coincided at the intermediate level, where the transfer between the visitors who went up and those who went down took place.

The third level

| Position | Dimensions | Surface | Construction | Height included television antenna: | |

| 276,13 m from the ground | Long: 18,65 m | 350 m2 | 1889 | 325 m from the ground | |

Situated 275 meters above the ground, with a surface area of 350 m², it can support the simultaneous presence of around 400 people.

Access is made by an elevator (the stairs are prohibited to the public from the second floor) and you reach a closed space full of orientation maps. Going up some stairs, the visitor arrives at an outside platform, sometimes referred to (erroneously) as the "fourth floor."

On this floor you can see a scene (similar to the ones in the «Grévin Museum») that shows Gustave Eiffel receiving Thomas Edison; this reinforces the idea that Eiffel would have used the place as an office, although the historical facts are different. In reality, the site had first been occupied by the meteorological laboratory, before it was used by Gustave Ferrié in the 1910s for his wireless telegraphy (TSH) experiments. The office shares this level with the Bar à Champagne, a small bar where you can enjoy glasses of sparkling wine while contemplating the city of Paris. Inside it there is a restaurant.

On top of the tower, a television broadcasting antenna was installed in 1957, which would later be completed in 1959 to cover about 10 million homes by broadcasting analogue terrestrial television. On January 17, 2005, the device was completed, when the French digital television broadcaster brought the total number of TV and radio broadcast antennas on the tower to 116. The addition of this 116th antenna increased the height of the tower from 324 to 325 meters.

Design

Materials

The puddled iron (wrought iron) of the Eiffel Tower weighs 7,300 tons, and the addition of elevators, shops, and antennas have brought the total weight of the construction to approximately 10,100 tons. As a demonstration of economy From the design, if the 7,300 tons of metal in the structure were cast, the 125 m square base could be filled with a depth of only 6.25 cm considering that the density of the metal is 7.8 tons per meter cubic. In addition, the square-based prism surrounding the tower (324 m x 125 m x 125 m) would contain 6,200 tons of air, with a weight similar to that of iron itself. Depending on the ambient temperature, the top of the tower can remove from the sun up to about 18 cm due to thermal expansion of the part of the structure exposed to the sun's rays.

Wind Considerations

When the tower was built, many were surprised by its bold shape. Eiffel was accused of trying to create an artistic element without regard to engineering principles. However, Eiffel and his team—experienced bridge builders—understood the importance of wind forces, and knew that if they were going to build the world's tallest structure, they had to be sure it could withstand it. In an interview with the newspaper Le Temps published on February 14, 1887, Eiffel said:

Isn't it true that the same conditions that provide resistance also meet the hidden rules of harmony?... So, what was the main phenomenon to worry about in the design of the Tower? It was the resistance to the wind. Well then! I argue that the curvature of the four outer edges of the monument, which is like mathematical calculation dictates that they should be... will give a great impression of strength and beauty, because it will reveal to the eyes of the observer the boldness of the design as a whole.

Graphical methods were used to determine the strength of the tower and empirical evidence to account for the effects of wind, rather than a mathematical formulation. Close examination of the tower reveals a basically exponential configuration. All elements of the tower were oversized to ensure maximum resistance to wind forces. The top half even avoids lattice-hole elements where possible. In the years since its completion, engineers have proposed various mathematical hypotheses in an attempt to explain the success of the design. In an analysis carried out in 2004, after the letters sent by Eiffel to the French Society of Civil Engineers in 1885 were translated into English, the calculation procedure used is described as a non-linear integral equation based in counteracting the wind pressure at any point on the tower with the tension between the building elements at that point.

The Eiffel Tower oscillates up to 9 centimeters due to the effect of the wind.

Maintenance

Maintenance of the tower includes the application of 60 tons of paint every seven years to prevent it from rusting. As of 2016, it has been completely repainted at least 19 times since it was built. Lead paints were still in use as recently as 2001, when the practice was discontinued for environmental reasons.

Aesthetics

File:Paris Eiffel 093.JPG Chaotic aspect of the jealousy of the tower's supports when they are observed from close.

| File:Eiffel tower underview.JPG Any symmetrical view return the structural order to the tower. |

The silhouette of the tower, practically from the moment it was inaugurated, became one of the most unmistakable and easily recognizable icons on an international scale. With its configuration reminiscent of a letter "A" capital letter, its design represented a radical break with what until then had been understood as a unique building. Deliberately ignoring the tradition of solid stone or brick constructions inherited from Imperial Rome through the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, it brought about a novel concept of building, which knew how to take advantage of the properties of a material that had acquired its technical maturity over the course of the XIX century: puddled iron. The immediate predecessor of steel, this material had allowed feats to be undertaken hitherto unimaginable in the construction of long-span bridges.

The main aesthetic achievement of Eiffel and his collaborators was having the audacity to turn the structure of the building (which until then was always modestly hidden between walls and walls, as an element as essential as it was uncomfortable), in the absolute protagonist of construction, in a kind of exoskeleton that transferred the language of engineering works to an unusual building due to its need to be both a 300 m high tower and an attractive and easily accessible place for the thousands of people who they were scheduled to visit the tower daily.

It is not surprising that when it was built, its contemporaries criticized its "unfinished" appearance, absolutely inconceivable for the mentality of the time. However, time has ended up proving its designers right, who With minimal ornamentation, they had the good sense to conceive a construction that was as functional as it was balanced. Curiously, the tower appears perfectly organized (thanks to its symmetry) when viewed as a whole; and at the same time, disconcertingly chaotic if you look closely at the dense set of its lattices.

The only non-structural elements are the four lattice arches, added in Sauvestre's sketches for aesthetic reasons, which served to give the tower greater symbolic importance as an impressive entrance frame to the exhibition.

Colour-wise, the tower is painted in three shades, with the lightest at the top and progressively darker towards the bottom, to perfectly complement the look of the Parisian sky. It was originally colored. reddish brown; which was changed in 1968 to a bronze color known as "Eiffel Tower Brown".

| Constructive details: | |||

| Detail of the arch construction. | North Pilar from the inside. | Top from the second floor. | View from the third floor down. |

The 72 names of scientists recorded

Gustave Eiffel had the names of seventy-two prominent scientists, engineers and mathematicians (almost all French) engraved on the tower in recognition of the discoveries they made, which according to Gustave Eiffel's own criteria, made them worthy of be inscribed on the tower. Eiffel chose this "invocation of science" because of his concern with the protest of artists.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the engravings were covered with the same paint used to protect the tower, but they were restored in 1986-87 by the Société Nouvelle d'exploitation de la Tour Eiffel, the company that operated the tower.

Lifts

The layout of the elevators has been modified several times during the history of the tower, improving their safety and capacity, although they have also ensured the conservation of the original machinery whenever possible:

- Original elevators

- When it was inaugurated in 1889, the tower had five hydraulic lifts. In the first week (where they were not yet working) about 30,000 people climbed on foot to the first level.

- 1889: On the ground floor, the tower had four hydraulic lifts: those of the east and west pillars, of a simple cabin, went up to the first level; and those of the north and south pillars, of double cabin, ascended to the second level. To climb from the second to the third level, the fifth elevator was used, which worked in two stages. Manufactured by the company "Edoux", it was a unique device in the world (it was dismantled in 1983). The upper cabin was driven by a hydraulic piston with a 81-metre tour, while the lower cabin was counterweight. In the middle of a tour, we had to change the elevator, crossing a walkway that allowed us to admire an impressive view.

- 1899: for the Universal Exhibition of 1900, the Roux-Combaluzier lifts of the east and west pillars were dismantled in 1887, replacing in 1899 with the Fives-Lille that have lasted to the present day, extending to the second level.

- 1910: the two Otis lifts were removed from the north and south pillars. They wouldn't be spares until 1965.

File:Ascenseur tour Eiffel - 20150801 16h58 (10632).jpg West pillar elevator. (A mannequin recreates one of the former operators).

|

- Current elevators

- At present the tower has a total of seven elevators: five between the street and the second level; and two others between the second level and the third.

- North Pilar: an electric lift "Schneider" (installed in 1965, and later modernized). Capacity: 920 people/hour.

- Pilar sur: an electric elevator "Otis" used exclusively since 1983 by the restaurant customers Le Jules Verne (located at the second level). Capacity: 10 people/ascense.

- South Pilar: a cargo elevator built in 1989. Capacity: 30 people or 4 tons/ascense.

- East and West Pillars: original "Fives-Lille" hydraulic lifts are maintained, subject to subsequent revisions. In 2008, the project was launched to restore to its original state the West pillar elevator, with the intention of re-using the simple operating machines devised by Gustave Eiffel in collaboration with the Fives-Lille company in 1899. Capacity: 650 people/hour each.

- Between the second and third levels: since 1983 there are two double cabin DUOLIFT-Otis electric lifts. When making the journey without the intermediate stop to perform the original hydraulic lift, the time of the tour was reduced from eight to less than two minutes. Capacity: 1140 people/hour

Taking into account the time needed to align the cabins at their stopping points, the elevators, in normal service, spend an average of 8 minutes and 50 seconds to make the round trip from the street to the second level, spending an average of 1 minute and 15 seconds on each level. The speed of the elevators is 2 meters per second. The average travel time between levels is 1 minute.

The original hydraulic mechanism of the elevator replaced in 1983 is on public display in a small museum located at the base. Because the mechanism requires frequent lubrication and maintenance, public access is often restricted.

Lighting

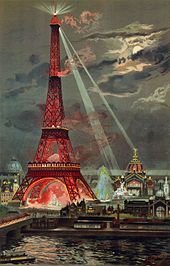

Since its creation, the Eiffel Tower has always been dazzlingly illuminated throughout its entire structure, either by gaslight (when it opened) or by high-pressure sodium or neon lighting. Since 1888, before After its completion, every July 14, fireworks are shot from the second floor of the tower, making it one of the favorite places for Parisians to celebrate France's national day. In 1889, when it was first illuminated, it consisted of 10,000 gas lights, but for the 1900 World's Fair in Paris, the gas lights were replaced by electric lights.

In addition to normal lighting, and the floodlights that sweep across the Parisian sky every night and are visible from fifty miles away if the sky is clear, the Eiffel Tower exhibits particularly striking and brilliant lighting when, after nightfall, during the first ten minutes of every hour (until 02:00 normally, and until 01:00 in winter) thousands of twinkling bulbs light up, giving it a spectacular appearance.

In 1925, André Citroën made a large advertising lighting consisting of more than 250,000 bulbs of different colors. These lights were maintained until 1933, when the city had already increased its size six times. the gardens of Trocadero.

In 1934, the Jacopozzi company installed a clock and thermometer along the length of the tower, with red bulbs representing the bar of mercury that marked the temperature.

In 1985, the SNTE (Société Nouvelle d'exploitation of the Eiffel Tower), decided to make an installation of yellow and orange lights that were placed inside the tower, which reflected the colors produced by 352 sodium vapor projectors. Shortly after, it was equipped with a device that would make it visible from many kilometers away: two beams of light were installed at the top of the tower, so that they can be seen from a distance of 80 km. This mechanism is composed of four motorized projectors ("Marine" brand) with 6000 watt xenon lamps that last 1200 hours. All the projectors receive orders from a micro-processor that keeps them synchronized to form a double cross that rotates 360° on the tower.

For the year 2000, the Eiffel Tower was adorned with 20,000 flashlights flashing above its structure. These flashes flash for ten minutes twice a day: the first time at noon and the second time at one o'clock at night. In addition, every hour the tower flashes with its thousands of flashes for five minutes, the last being at one in the morning for ten minutes, but without its usual lighting.

Installation required:

- 20 alpinists every night for three months to place the luminaries.

- 20 000 lights, with a total weight of eight tons.

- 800 electric lights, of 13 kilos each on average, with a total length of 18 km.

- 60 000 flexible collars to attach the cables to the tower and 20 000 joints to join them.

- 230 switches and more than 30 km of cables.

- 400 kW of power for lighting.

In June 2003, the Eiffel Tower launched a plan to place 2,000 flashes, but with a new technique. At 1 in the morning in winter or at 2 in the morning in summer, the lights overlap creating a mixture of lights for 10 minutes that simulate a muted gold color.

During the second half of 2008, between June 1 and December 31, France held the rotating Presidency of the European Union. During this period, some monuments and buildings in Paris had specific lighting designed for the occasion. Specifically, the Eiffel Tower was illuminated in blue, and twelve stars were placed on the north face of the monument, between the first and second floors. yellow symbolizing the European Union. The inauguration ceremony of the lighting, chaired by the French Minister of Foreign and European Affairs Bernard Kouchner, was attended by the twenty-six ambassadors of the countries of the Union in Paris.

Restaurants

When it opened in 1889, the tower already had three restaurants on the first floor with a capacity of 500 seats each (French, Russian and Flemish) and an Anglo-French bar. Until 1900, they were lit with gas lights. After the end of the 1889 Exposition, the Flemish restaurant became a theater with 250 seats.

On the occasion of the 1937 Exposition, all four were demolished, only two of them being rebuilt. At the beginning of the 1980s, the first floor of the tower was remodeled again, opening two haute cuisine restaurants: La Belle France and Le Parisien, which in turn in 1996 became the Altitude 95 restaurant (with a decoration inspired by the era of airships). In 2008 it was remodeled again, becoming the current restaurant Tour Eiffel 58.

For its part, the restaurant Le Jules Verne was inaugurated in 1983 under the direction of chef Alain Reix. After a period of inactivity, it reopened its doors in December 2007 under the direction of Alain Ducasse.

Since the origins of the tower, restaurants have served both as a tourist attraction and as one of the economic supports for their exploitation. Currently, it has five gastronomic businesses:

- The restaurant Tour Eiffel 58 on the first floor (completely renovated in 2008), with 250 dining rooms between their two floors. Quick French-style food is served.

- La Room Gustave Eiffel also on the first floor (totally renovated in 2013), is a meeting place that can be enabled as a dining room for 130 dining rooms.

- The prestigious restaurant Le Jules Verne, which has been installed on the second level of the tower since 1983, has 280 capacity places, and offers recipes of high cuisine. Directed since 2007 by Chef Alain Ducasse, it has a Michelin Star renewed in 2016.

- The Bar à Champagne, is a small bar located on the third floor, dedicated to the tasting of champagne.

- The Buffet Tour Eiffel, which has three establishments (ground floor, first floor and second floor), where food and beverages are sold to be tasted while the tower is visited.

Other dependencies

In the upper part, there were laboratories for various experiments, and a small apartment reserved for Gustave Eiffel, used to attend to his guests. It is currently open to the public, including period decoration and mannequins representing Eiffel and some of its notable visitors.

The tower has two underground facilities that can be visited on tours organized by SETE:

- Military use basement in time of war: during the First World War the Eiffel Tower was used to host the communications equipment of the French army, so that an underground evacuation route was built with several secret corridors and tunnels leading to a coal tank located next to the Seine River, designed as a way of escape in case Paris was invaded. Today, the bunker is used as a warehouse and hosts the air conditioning system that feeds the restaurants of the tower and the gift shop.

- Underground machinery room: hosts the powerful machinery that drives the hydraulic elevators of the tower. Still in full operation, it is said to be more efficient than the modern electric elevators that run the tower. Hydraulic elevators came into service in 1899, and since then the veteran infrastructure has been kept in its underground housing located under the tower.

To the southwest of the west pillar of the Eiffel Tower is a red brick chimney, hidden among some bushes at the edge of a small pond. It has remained in this place since the tower was created in 1887. It was used to evacuate the smoke from the steam boilers that supplied power to the machinery used in the south pillar during its construction.

In May 2016, accommodation was created on the first level to accommodate the four winners of a competition organized on the occasion of the Euro 2016 soccer tournament held in Paris. The apartment has a kitchen, two bedrooms and a living room.

Power generation

In March 2015 two wind turbines were installed above the first level (two 5 m high vertical helical turbines, designed and manufactured with composite materials by the company "Urban Green Energy" ), with the capacity to generate 10,000 kWh per year, enough to cover the consumption of the commercial areas on the first level.

History

Chronological approach

The Third Republic and the development of techniques

Conceived in 1884, built between 1887 and 1889, and inaugurated for the 1889 World's Fair in Paris, the Eiffel Tower today symbolizes an entire country. However, it was not always like that, and in its origins it was just one more element of the image with which France wanted to show the world the economic strength of the country.

Since 1875, the nascent Third Republic, which was characterized by chronic political instability, could barely sustain itself. In government, political parties followed one another at a constant pace. According to Léon Gambetta (prime minister between 1881 and 1882), the cabinets were often made up of "opportunist" freedom of the press etc.

The society of the time pays great attention to technical progress and social progress. It is this belief in the benefits of science that gave rise to the world's fairs. But already from the first exhibition (Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations; the "Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations", London, 1851), the rulers quickly perceive that an effective political showcase is taking shape behind the technological commitment, and it would be a mistake not to take advantage of the opportunity. By demonstrating its industrial prowess, the host country can show off its advancement and its superiority over the other European powers, which then reigned in the world.

Under this vision, France repeatedly hosted the Universal Exposition, in the years 1855, 1867 and 1878. Jules Ferry, president of the Council from 1883 to 1885, decided to revive the idea of holding a universal exposition in France. On November 8, 1884, he signed a decree that officially established the celebration of a Universal Exposition in Paris from May 5 to October 31, 1889. The year chosen was not random, because it symbolizes the centenary of the French Revolution.

Paris is once again the "center of the world", although the situation is evolving rapidly, and it is on the other side of the Atlantic, in the bosom of the young economic powerhouse of the United States, that the idea of a tower will truly be born of 300 meters. Indeed, at the time of the Universal Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876, the American engineers Clark and Reeves envisioned the project of a cylindrical pole 9 meters in diameter supported by metal shrouds, anchored to a circular base 45 meters in diameter, with a total height of 300 meters. Due to lack of credits, his project will never see the light of day, although in 1874 it would be published in the United States (in the Scientific American magazine), and in France (in the magazine La Nature).

In the same situation, the French engineer Sébillot showed in the United States the idea of an iron “sun-tower” that would illuminate Paris. To do this, he teamed up with the architect Jules Bourdais, who was working on the project for the Trocadero Palace for the Universal Exposition of 1878. Together, they conceived a project for a & # 34;tower-lighthouse & # 34; of granite, 300 meters high that will go through several versions, which will later compete with Gustave Eiffel's tower project, and which will never be built.

A significant precedent for all these projects was the Latting Observatory, a 300-foot-tall, pointed pyramid with an iron and wood frame, built in New York for the All Nations Industrial Exposition of 1853. Access to the tower, which featured steam-powered elevators, was free.

The elaboration of the project

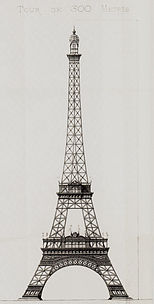

In June 1884, two engineers from the Eiffel company, Maurice Koechlin and Émile Nouguier, head of the design office and head of the methods office respectively, studied the project for a 300-meter metal tower. They hope to make it the center of attention at the 1889 Exposition.

On June 6 exactly, Maurice Koechlin made the first sketch of the building. The drawing represents a tower 300 meters high, where the four curved faces are joined by platforms every 50 meters until reaching the top. Gustave Eiffel says he is not interested in the project, although he grants the two designers permission to continue with the study. Called in to collaborate on the project, Stephen Sauvestre, chief architect of the Eiffel company, completely redraws the building to give it a new dimension: he adds a heavy masonry footing and links the tower to the first floor with arches, reduces the number of platforms from five to two, and makes the tower's design look more like a lighthouse, among other changes.

This new version of the project, embellished with decorative varnish, is once again presented to Gustave Eiffel, who on this occasion is enthusiastic about the project; to such an extent that he deposited, on September 18, 1884, in his name and those of Koechlin and Nouguier, a patent for "a new provision that allows the construction of piles and metal towers with a height greater than 300 meters". A short time later he bought the rights of Koechlin and Nouguier, to obtain exclusive ownership of the future tower that, for now, bears his name.

The genius of Gustave Eiffel does not reside so much in the conception of the monument, as in the energy he used to make his project known to the rulers, those responsible for the administration and the general public; and when he succeeded, in gathering the necessary investment to be able to build the tower, which in everyone's eyes, continued to be a simple architectural and technical challenge or a purely aesthetic object (or unsightly according to others). He also financed with his own funds some scientific experiments carried out on or from the Eiffel Tower, which allowed it to perpetuate it.

First, he tried to convince Édouard Lockroy, the Minister of Industry and Commerce at the time, to launch a competition that would “explore the possibility of raising on the Champ de Mars an iron tower with a base of 125 m² and a height of 300 meters”. The modalities of this contest, carried out in May 1886, are so similar to the project defended by Gustave Eiffel that one could almost believe that it was written by his own hand. Of course, Eiffel did not, but it is clear that his project had a good chance of being chosen to appear in the Universal Exposition that would take place three years later. He still has to prove that it is not a merely ornamental object, but that it can fulfill other functions. By foregrounding the scientific interest in the tower, he undoubtedly scores some points for himself.

Eiffel does not know in advance the result of the contest. The competition gets tough. 107 projects are presented, but Gustave Eiffel finally wins the competition, allowing him to build his tower for the 1889 World's Fair, like Jules Bourdais, who will do the same with the Trocadero Palace (where he preferred to use granite instead of of iron).

Two problems immediately arise: the elevator system does not satisfy the selection panel, which forced Eiffel to change suppliers; and the location of the monument. Initially, it was considered to place the building right next to the Seine or next to the Old Palace of the Trocadero (now Palais de Chaillot), but finally it was decided to place it right on the Champ de Mars, site of the Exposition, and make the tower a kind of monumental gate.

The location and the manner of construction and operation will be subject to an agreement signed on January 8, 1887 between Édouard Lockroy, Minister of Commerce, acting on behalf of the French State, Eugène Poubelle, Prefect of the Seine, acting on behalf of of the city of Paris and Gustave Eiffel, acting on his own behalf and not on behalf of his company. This official act specifies the estimated cost of construction, which will be 6.5 million francs paid at that time, in addition to contribute up to 1.5 million francs for unforeseen expenses (article 7); the rest will be paid by a public limited company created by Gustave Eiffel and financed by himself and a consortium of three banks, whose specific purpose will be the exploitation of the tower. The text also establishes a series of provisions, such as:

- The price of tickets during the Universal Exhibition (article 7)

- That 300 tickets per month will be free

- That on each floor a special room should be reserved for scientific or military experiments

- to be available free of charge to persons designated by the Commissioner-General (article 8)

Finally, Article 11 stipulates that:

After the exhibition and at the time of the delivery of the park of the Campo de Mars, the city will become the owner of the tower, with all the benefits and related costs; but Mr. Eiffel, as a supplementary prize for its work, will retain the benefits on the building until the expiration of a period of twenty years, which will be due from January 1, 1890; the end of the period, these benefits will be returned to the City of Paris. The delivery of the tower will take place after these twenty years, will be delivered in good condition of use and maintenance, although Mr. Eiffel special repairs.

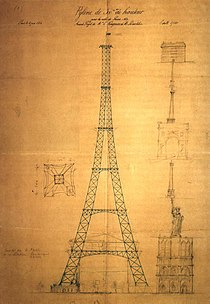

Project technical documentation:

The project required the definition of 18,038 metal parts and the completion of 5,300 workshop drawings with their corresponding plans, in which 50 engineers and 150 operators were involved in the Levallois-Perret factory.

Numerous technical plans of the Eiffel Tower were published in the work "La Tour de 300 mètres" (The Tower of 300 meters) (Paris: Lemercier, 1900 - 2 vol. T I: Texte TII: Planches.), in which Gustave Eiffel himself, ten years after the completion of the construction of the tower, made a synthesis of its main characteristics and the laborious steps necessary for it to finally be built.

| Some original planes (examples): | |||

| Cimentations. | Jealousy. | Support one of the pillars. | Detail of the upper flashlight. |

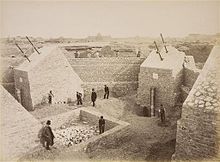

Building the tower

Initially, Gustave Eiffel (engineer and specialist in metal structures) had planned twelve months of work, although in reality it took twice as long. The construction phase began on January 28, 1887 and ended in March 1889, before the official opening of the World's Fair.

On site, the number of workers never exceeded 250. This was because much of the work was done upriver, in the factories of the Eiffel companies located in Levallois-Perret. Of the 2,500,000 rivets in the tower, only 1,050,846 were placed on site, 42% of the total. The vast majority of the elements are assembled in the Levallois-Perret workshops, on the ground, in pieces five meters, with provisional bolts; and only later, in situ, are they definitively replaced by hot-set rivets (rivets).

The construction of the pieces and their assembly are not the result of chance. Fifty engineers made 5,300 drawings of the assembly or some details over two years, and each of the 18,038 pieces of iron had its own descriptive scheme. At the construction site, in the first instance, the workers make the huge concrete plinths that will support the four pillars of the building. This helps reduce the pressure on the ground of all the pieces, which together exert a pressure of 4.5 kg/cm² at the foundation level.

The assembly of the metal parts themselves began on July 1, 1887. The men responsible for assembling this "Giant Meccano" are called flyers and are directed by Jean Companion. The pieces are raised up to 30 meters high with the help of pivot cranes attached to the elevators. Between 30 and 45 meters high, 12 wooden scaffoldings are built. Once the height of 45 meters was exceeded, new scaffolding had to be built, adapting the 70-ton beams that were used for the first floor. Then followed the joining of these huge beams with the four edges at the level of the first floor. This union was carried out without incident on December 7, 1887 and made temporary scaffolding unnecessary, replaced at first by the first platform (57 meters high), and later, from August 1888, by the second platform (at 115 meters).

In September 1888, while the work was well advanced and the second floor was built, the workers went on strike. They argue about work hours (9 hours in winter and 12 hours in summer), as well as their salary, which they considered low taking into account the risks assumed. Gustave Eiffel argued that the risk was no different if you worked at 200 or 50 meters high. Despite the fact that the workers were paid better than the average salary for workers in the sector, he grants them a salary increase, but refuses to compensate them on the factor that "the risk varies according to height" (which was demanded by the workers). Three months later, a new strike will break out, but this time it will clash with the workers and deny any negotiation.

In March 1889, the monument was finished on time and no fatal accident was recorded among the workers (however, a worker died, but it was a Sunday, he was not working and he lost his balance during a demonstration for his fiancée). The work cost 1.5 million francs more than expected, and it took twice as long to be built as initially planned in the contract signed in January 1887.

The completed building was open to the public up to the third platform. The elevators from the Backmann company, which were initially provided for in the project presented in the May 1886 competition, were rejected by the jury. Gustave Eiffel turned to three new suppliers: Roux-Combaluzier et Lepape (now Schindler) (ground floor to first floor, east and west sides), the American company Otis (ground floor and second floor, north and south sides) and an acquaintance from Eiffel, Léon Edoux (second floor to the top).

(The following sequence of photos is from gallica.bfn.fr "La tour de 300 mètres 1900")

- Photographic sequence of the construction of the tower from July 1887 to March 1889:

Inauguration

The main structural work was completed at the end of March 1889, and on the same day, March 31, Eiffel celebrated by guiding a group of government officials (accompanied by representatives of the press), to the top of the tower. Because the elevators were not yet in operation, the ascent was done on foot, taking over an hour, with Eiffel stopping frequently to explain the various features of the structure. Most of the group stayed on the two lowest floors, but a few, among them the structural engineer Émile Nouguier (the director of the work), Jean Compagnon (President of the City Council), and the reporters from Le Figaro and Le Monde Illustré, completed the ascent. At 2:35 p.m., Eiffel raised a large tricolor flag to the accompaniment of a salvo of 25 cannon shots from the first level.

There was still a lot of work to be done, especially on the elevators and facilities, and the tower was not open to the public until nine days after the exhibition opened on May 6. Even then, the elevators had not been completed. The tower was an instant hit with the public, with nearly 30,000 visitors coming up to visit it. As night fell, the tower was illuminated by hundreds of gas lamps, and a beacon sent out three beams of red, white, and blue light. Two floodlights mounted on a circular rail were used to illuminate other buildings in the show. The opening and closing of the exhibition was announced daily by a cannon located at the top of the tower.

On the second level, the French daily Le Figaro had an office and a printing press, where a special commemorative edition, Le Figaro de la Tour, was made. At the top, a post office was installed, from where visitors could send letters and postcards as a souvenir of their visit. Sheets of paper were also posted on the walls each day for visitors to record their impressions of the tower. Gustave Eiffel described some of the public's notations as vraiment curieuse ("truly curious").

The Eiffel Tower from 1889 to World War I

On May 6, 1889, the Universal Exposition opens its doors to the public, who can climb the Eiffel Tower from May 15. While it had been discredited during its construction, particularly in February 1887 by some of the most famous artists of the time, the Eiffel Tower achieved immediate popular success during the Exhibition, gaining the support of visitors. Since the first week, despite the fact that the elevators did not start working until May 26, 28,922 visitors walk up to the building and even 1,710 of them took the stairs to the top.

Finally, of the 32 million entries to the Exposition, around two million tourists visit the tower. The monument, then the tallest in the world (and would be so until 1930, when the Chrysler Building was built in New York), also attracts some well-known personalities and friends of Gustave Eiffel.

A list of famous visitors to the tower during the Exhibition include the Prince of Wales, actress Sarah Bernhardt, "Buffalo Bill" Cody (his Wild West demonstration was one of the attractions of the Exposition) and Thomas Edison. Eiffel invited Edison to his private apartment at the top of the tower, where Edison presented him with one of his phonographs, one of new inventions that was one of the highlights of the show. Edison signed the guest book with this dedication:

For the engineer Mr. Eiffel, the endeavored builder of this gigantic and original display of modern engineering, of someone who has the greatest respect and admiration for all engineers, including the Great Engineer, the Good God. Thomas Edison.

The Eiffel Tower is not the only monument that draws crowds: the immense Galerie des machines (Gallery of Machines, 440 meters long by 110 meters wide) by Ferdinand Dutert and Victor Contamin or the central Dôme (central dome) by Joseph Bouvard also attract the public. But the real novelty is the widespread use of electricity, which allows amazing light effects for the time.

But once the Exhibition is over, curiosity quickly declines and with it the number of visitors. In 1899, only 149,580 tickets were recorded. In order to relaunch the commercial exploitation of his tower, Gustave Eiffel lowered the price of admission tickets, but this did not affect sales.

We will have to wait for the Universal Exposition of 1900, once again held in Paris, for the number of onlookers to increase again. On this occasion, more than a million tickets are sold, which is well above the figures of the previous ten years, but well below what is necessary for the maintenance of the tower. Indeed, not only are tickets twice as numerous as in 1889, but the decline in sales is even more worrying considering the fact that visitors to the Universal Exposition of 1900 were more numerous than in 1889. For this event, the elevators in the east and west pillars were replaced by elevators reaching the second level, built by the French firm Fives-Lille. They were equipped with a compensation mechanism to maintain the ground level depending on the angle of ascent, and were driven by a hydraulic mechanism similar to that of the Otis elevators, although these were installed at the base of the tower. Hydraulic pressure was provided by pressurized accumulators located near this mechanism. At the same time, the elevator in the north pillar was replaced by a stairway up to the first level. The design of the first two levels was modified, providing the necessary space for visitors on the second level. The original south pillar elevator was removed 13 years later.

The fall in the number of entries continues since 1901, so the future of the tower is not assured after December 31, 1909, the end of the stipulated concession. Some even support the idea that it can be demolished.

The Tower from the First World War to the Second

At the outbreak of World War I in 1914, a receiver located in the tower intercepted enemy radio communications, seriously hampering the German advance on Paris, contributing to the Allied victory at the First Battle of the Marne. Since 1925 until 1934, the advertising lighting of the Citroën automobile company was installed adorning three of the sides of the tower, in the possibly highest advertisement in the world of this time.

It was in the year 1925 that on two separate but related occasions, the swindler Victor Lustig "sold" the steel from the tower for scrap. In May 1929, the bust of Gustave Eiffel located on the north pillar, the work of Antoine Bourdelle, was unveiled. In 1930, the tower lost the title of the world's tallest structure when the Chrysler Building in New York was completed. In 1938, the existing decorative arcade around the first level was removed.

In April 1935, the tower was used for some experimental television transmissions (still very low resolution), using a 200-watt shortwave transmitter. On November 17, an upgraded 180-line transmitter was installed.

The management company of the tower changes and the tower undergoes a major modification on the occasion of the Specialized Exhibition of 1937: the old-fashioned decorations on the first floor are removed and new lighting is installed.

The Tower after World War II

After the German occupation of Paris in 1940, the elevator cables were sabotaged by the French. The tower was closed to the public during the occupation and the elevators were not repaired until 1946. In 1940, German soldiers climbed the tower to raise the swastika, but the flag was so large that it fell only hours later, and was replaced by a smaller one. During his visit to Paris, Hitler decided not to climb the tower.

Starting in 1942, the German army installed a powerful television station in the tower (called Fersenhender Paris), which, directed by Kurt Hinz, regularly broadcast several hours of programming a day.

In August 1944, as the Allied Army approached Paris, Hitler ordered General Dietrich von Choltitz, the military governor of Paris, to demolish the tower along with the entire city. Von Choltitz disobeyed the order. On June 25, before the Germans had been expelled from Paris, two employees of the Museum National de la Marine Francesa replaced the Nazi flag with a tricolor, and were about to attack the three men led by Lucien Sarniguet, who had lowered the French flag on June 13, 1940, when Paris fell to the Germans. The tower, which had managed to survive a fire set by troops German, it was used to communicate with troops, first by the Wehrmacht and then by the Allies during the Liberation of Paris.

On January 3, 1956, a fire broke out in the television transmitter, damaging the top of the tower. Repairs lasted a year and in 1957, the current radio antenna was added to the top. In 1964, the Eiffel Tower was officially declared a historic monument by the Ministry of Cultural Affairs headed by André Malraux. A year later, an additional lifting system was installed on the north pillar.

Starting in 1960, international mass tourism began to grow, which had direct consequences on the number of visitors to the tower, which increased rapidly to reach 6 million visitors per year (limit exceeded in 1998), which requires a renovation of the tower. Extending to 1985, the tower is remodeled focusing on three main features: the lightening of the building structure; the total reconstruction of the elevators and stairs; and the creation of security means adapted to the popular success of the tower. In this way, the Eiffel Tower will be relieved of 1,340 superfluous tons, it will be repainted and treated against corrosion, the elevators on the third platform will be replaced, the gourmet restaurant Le Jules Verne will be inaugurated and the will install a lighting device made up of 352 sodium vapor projectors.

According to some interviews, in 1967, Jean Drapeau (Mayor of Montreal) negotiated a secret agreement with Charles de Gaulle for the tower to be dismantled and temporarily relocated to Montreal to serve as a landmark and tourist attraction during Expo 67. The plan was reportedly vetoed by the company that operated the tower for fear that the French government might later deny permission for the monument to be restored to its original location.

Starting in the 1970s, the Eiffel Tower gained popularity and earned a place in the global collective spirit, as well as becoming one of the best-known symbols of France.

In 1982, the original elevators between the second and third levels were replaced after 97 years in service. These had been closed to the public between November and March because the water in the hydraulic unit tended to freeze. The new cabins operate in pairs, serving as counterbalances to each other, and make the journey in a single leg, reducing travel time from eight minutes to less than two minutes. At the same time, two new emergency stairs were installed, and the original spiral stairs were replaced. The Fives-Lille elevators in the east and west pillars, installed in 1899, were totally renovated in 1986. The cabins were replaced, and a computer system was installed to fully automate them. The water-based hydraulic system was replaced with a new electrically-powered oil-hydraulic system. The south pillar service lift was reserved three years later for moving small loads and maintenance personnel.

On December 31, 1999, for the "Countdown to the Year 2000" party, flashing lights and high-powered projectors were installed on the tower, accompanied by a large fireworks display. An exhibition next to the first floor cafeteria commemorates this event. The searchlights at the top of the tower formed a beacon in the Paris night sky, and 20,000 flickering lamps gave the tower a glowing appearance for five minutes every hour. The lights shone blue for several nights to announce the arrival of the tower. new millenium. This illumination continued for 18 months until July 2001. The brilliant lights (designed to last 10 years without maintenance) were turned on again on June 21, 2003.

The tower received its 200,000,000th visitor on November 28, 2002, making it the fifth most visited monument in France. The tower has operated at its maximum capacity of approximately 7 million annual visitors since 2003. In 2004, a removable ice skating rink was installed on the first level. A glass floor was installed on the first level during rehabilitation of the year 2014.

On January 1, 2006, a new administration period of 10 years began, with the concessionaire being the mixed economy company SETE (Sociedad de Explotación de la Torre Eiffel), although 60% of the capital is held by the city of Paris.

List of tower operators

The texts that declare the operators of the Eiffel Tower are the following:

- Convention of 8 January 1887, signed by Gustave Eiffel, Edouard Lockroy and Eugène Poubelle. The use of the tower is authorized to Gustave Eiffel in its own name, from the opening day to the public of the Universal Exhibition of 1889 until 31 December 1909. (See text [in French]: p. 1 - p. 2 - p. 3 - p. 4 - p. 5 - p. 6 - p. 7).

- Extension of authorization for the management and exploitation of the Eiffel Tower to Gustave Eiffel, for a period of 70 years, with effect from 1 January 1910.

- Deliberation of the Council of Paris on 17 February 1981 (“referring to the award of the Eiffel Tower”), granted to the SNTE for a period of twenty-five years, from 1 January 1981 to 31 December 2005.

- Deliberation of the Paris Council on 13 December 2005 (file number: 2005 DF 92).

- Attribution of the delegation of public services for the management and exploitation of the Eiffel Tower, granted to SETE for a duration of 10 years, beginning on 1 January 2006 (see text [in French]).

Thematic focus

The tower seen by the artists

- Initial resistance

Some articles, often propaganda, are published throughout the year 1886, even before construction work began. In February 1887 about three hundred artists (writers, painters, composers, architects, etc.) joined forces to denounce "the useless and monstrous Eiffel Tower" in the now famous open letter "Protest of artists against the tower of Mr. Eiffel». Among these artists were: Guy de Maupassant, Charles Gounod, Victorien Sardou, Charles Garnier, François Coppée, Sully Prudhomme, Leconte de Lisle, William Bouguereau (all pictured on the right, in order from top to bottom, left to right), as well as Alexandre Dumas Jr., Ernest Meissonier, Joris-Karl Huysmans and Paul Verlaine.

In the letter you could find qualifiers for the tower such as:

- «This truly tragic street lamp» (Léon Bloy)

- «This watchtower skeleton» (Paul Verlaine)

- "This mast of hard, unfinished, confusing, deforming iron" (François Coppée)

- «This tall, thin pyramid of iron scales, giant skeleton lacking of grace, whose basis seems to be made to carry a formidable monument of Cyclops, abortion of a ridiculous and thin profile of factory chimney» (Guy de Maupassant)

- "A factory tube under construction, a frame that expects to be covered by stones or bricks, this infundibuliform wire, this hole-wrapped suppository" (Joris-Karl Huysmans)

Among the tower's few defenders was poet and later Nobel laureate Sully Prudhomme, who had changed his mind after being one of the prominent signatures on the artists' rejection letter, and publicly extolled the making of Eiffel for a speech delivered two years later.

However, later some modern authors considered the tower as a powerful symbol in particular, and an expression of avant-garde in general. A clear example is the essayist Roland Barthes, who in the 1960s analyzed the transformation over time of the symbolic meaning of the tower, until it became an unequivocal reference to Paris and France.

- Cinema and television

As soon as the interest in film reporting for engineering began to develop, the Eiffel Tower was surrounded by the most illustrious filmmakers, but in the first instance, only in the form of a documentary (Panorama during the ascent of the Eiffel Tower, Louis Lumière, 1897); Images from the 1900 exhibition, Georges Méliès, 1900). The first fiction with the Eiffel Tower as the main decoration is a French medium-length film, Paris qui dort (Paris that sleeps, René Clair, 1923). In this short film (35 minutes), a scientist plunges Paris into a dream and a handful of men and women take refuge on the heights of the Eiffel Tower, beyond the fate of the other inhabitants of the capital.

In 1930, with La Fin du monde (The End of the World), Abel Gance directed the first feature film (1 hour 45 minutes) and promoted research to highlight the beauty of the tower structures.

In the 1940s, the images transmitted by the Eiffel Tower began to be integrated into American films. In this way, Ninotchka, one of the greatest successes of the American director of German origin Ernst Lubitsch, uses the images of the Eiffel Tower in a symbolic way. In 1949, Burgess Meredith made L'Homme de la tour Eiffel (The Man on the Eiffel Tower), the first film adaptation of a novel by Georges Simenon. Charles Laughton plays Commissioner Maigret (although he appears as an inspector), who pursues a double murder suspect obsessed with the Eiffel Tower, causing the building to appear several times, including a fast-paced final scene.

On June 4, 1966, the first important telefilm with a report on the Eiffel Tower was broadcast, La Rose de fer (The Iron Rose), 39th episode of the first series Cinq Dernières minutes (The last five minutes, 1958-1973). Starting in the 1980s, the Eiffel Tower will appear in various American productions, such as in 1985, when it was filmed in the movie A View to Kill (A View to Kill). He also appears in the movie Rush Hour 3 (Rush Hour 3). And it's also part of a sequence from Superman II, right at the beginning of the movie.

Afterwards, the appearances of the tower in American cinema will be more and more frequent, particularly for practical and symbolic reasons. It allows, in fact, to signify in a single shot or a single sequence, even a very short one, that the action takes place in France, or in Paris. Already in 1953, Byron Haskin shows it destroyed in his adaptation of The War of the Worlds. This type of image (with the Eiffel Tower destroyed) will often be used in American films to signify an immediate and serious planetary danger, as in the 1996 film Independence Day and Martians Attack (Mars Attacks!), or in Armageddon in 1998, in Alien: Resurrection by Jean Pierre Jeunet in 1997 and in G.I. Joe: The rise of Cobra by Stephen Sommers in 2009.

- Photography

Since Luis Emile Durandelle, who took the famous views of the construction of the tower, numerous internationally renowned photographers have made the tower the object of their photographs, either as a background object or as a central theme.

- Historieta

The comic best known for its use of the Eiffel Tower is perhaps Adèle Blanc-Sec, T2: Le Démon de la tour Eiffel (Adele Blanc-Sec, T2: The Demon of the Eiffel Tower) by Jacques Tardi. The Eiffel Tower appears on the cover of S.O.S. Meteors (S.O.S. Metéores: Mortimer à Paris; volume 8), an album in the Blake and Mortimer series drawn by Edgar P. Jacobs, playing, however, a minor role in the story.

Although not strictly speaking a comic, André Juillard produced 36 views of the Eiffel Tower, as did Hokusai with his Thirty-six views of Mount Fuji (Engravings, 1831) and Henri Rivière with his 36 views of the Eiffel Tower (Lithographs, 1902).

- Literature

In literature, the Eiffel Tower has been addressed more than once by writers. Whether as the central theme of a book or as a simple setting, it has dotted literary creation from the XIX century to the present day.. But as its effect of novelty and fashion wears off, the monument appears less and less frequently in contemporary literature of the late 19th century and the first half of the 20th century. It should also be noted that the authors who have dealt with the construction are mostly French, or at least French-speaking.

At the time of its construction and early commissioning, the monument was the subject of personal critical analysis, most of the time published in newspapers of the time, and on many occasions such criticism was negative. The themes treated by the artists were, most of the time, focused on the technical, industrial and commercial challenge that the tower represented at that time. They also criticized its influence on the image of France abroad, the aesthetic (or unsightly) aspect of the tower, and its potential scientific interest (or its uselessness).

Subsequently, due to its success among the public, many writers revoked their considerations and their previous criticisms disappeared. It is undoubtedly Roland Barthes who best describes this feeling of attraction/repulsion of artists in front of the Eiffel Tower:

Look, object, symbol, the tower is all that man puts on it and this everything is infinite. Watchful spectacle and observer, useless and irreplaceable building, family world and heroic symbol, witness of a century and ever-new monument, inimitable and unceasingly reproduced object, is the pure sign, open to every time, to all images and to all senses, the metaphor without brake; through the tower, men carry this great function of the imagination, which is their freedom, since no story, however much somber.Roland Barthes, The Eiffel Tour, Editorial Delpire, 1964.

In novels, it has been approached in various ways: Léon-Paul Fargue assesses the critical analysis of his peers during the early days of the tower (The Pedestrian of Paris, 1932-1939), together with Pierre Mac Orlan, while recalling that in the beginning, for the artists "to inveigh against the tower [...] was a patent of literary and artistic sensibility". Other authors highlight the scientific and military interest that was later recognized in the tower (La Tour, Javel et les Bélandres, Villes, en Œuvres complètes).

Finally, others such as Pascal Lainé focus on the history of the tower's design, construction and initial years of operation through a romantic narrative (The Mystery of the Eiffel Tower, 2005). On this same subject, Dino Buzzati, in his work Le K., makes a fictitious staging of workers who worked on the construction of the tower during 1887 and 1889. However, Buzatti proceeds in a different way from Lainé, and his text is structured as a news series, not as a story. The tone used is fantastic and not realistic like that of Pascal Lainé.

In poetry, Guillaume Apollinaire made a nationalist calligram on the tower (Calligrammes, 1918), a text that René Étiemble considers in his work "Essais de littérature (vraiment) generate" (Essays in (Truly) General Literature), as an example of Western haïku ("Shepherds ô Eiffel Tower / The herd of bridges / Bullet this morning").

In July 1888, François Coppée attacked the tower, which he refers to as an "iron mast difficult to tackle/Unfinished, confused, deformed", as well as a "symbol of unnecessary force", "monstrous and job loss” or even “ridiculous mast” (On the Eiffel Tower, the second plateau, Poems). In May 1889, through a poem in which he gave voice to the Tower, Raoul Bonnery replied: "You put the flower of your science/By calling me a "horrific monster"/A little more recognition/I would have convinced you a little more », or also «What blood circulates in your veins/ To exclaim with contempt,/ That I am a ridiculous mast/ On the ship of Paris./ A mast? I accept the epithet,/ But a proud and bold mast,/ Who will know, holding his head high,/ Talk of progress to the heavens.» (The Eiffel Tower to François Coppée, the day of the 300 meters, in Le Franc journal). Unlike the previous examples, Vicente Huidobro, Blaise Cendrars and Louis Aragon pay homage to the tower (in their respective works North-South, No. 6-7, from 1917; La tower in 1910 in Nineteen Elastic Poems, from 1913; and The Tower Speaks in The Eiffel Tower by Robert Delaunay). Pierre Bourgeade, in a news item entitled The Suicide, recounts, via the testimony of a guard, the suicide of an unknown woman who has jumped from the third floor of the tower (in The Immortals, Gallimard, 1966).

In the theater, the tower treated in the pieces A visit to the 1889 exhibition, a light comedy in three acts and 10 scenes (Henri Rousseau) and The Bride and Groom of the Eiffel Tower (Jean Cocteau, 1921).

The Champ de Mars monument has also been treated in particular ways: as a newspaper article (Jules de Goncourt and Edmond de Goncourt, Journal, volume VIII, May 6 and July 2, 1889); as a travel tale (Guy de Maupassant, La vie errante, 1890), where the writer expresses his boredom with the Eiffel Tower; or as a semiological study (Roland Barthes, The Eiffel Tower, 1964); but it has also been addressed as a preface to books, in numerous conferences, or in magazine articles.

- Music

The Eiffel Tower has also attracted numerous singers. Its location has exceptional possibilities for large events, both for artists and the public. Thus, on September 25, 1962, for the launch of the film The Longest Day, producer Darryl F. Zanuck organized a large-scale musical show in Paris; On this occasion, Édith Piaf, accompanied by 1,500 rockets of fireworks, sang from the first floor of the tower in front of 25,000 Parisians. In 1966, for the launch of the world campaign against hunger, Charles Aznavour and Georges Brassens sang there.

On July 14, 1995, it was Jean-Michel Jarre's turn to give a concert at the foot of the Eiffel Tower to celebrate UNESCO's 50th anniversary, before more than a million spectators.

In 1998, José Carreras, Plácido Domingo and Luciano Pavarotti, The Three Tenors, performed on the Champ de Mars before an audience of 200,000, with the illuminated Eiffel Tower as a backdrop.

Likewise, on June 10, 2000, Johnny Hallyday offered a concert and a fireworks display there in front of 600,000 people, and later recorded his album 100% Johnny: Live a La Tour Eiffel.

- Painting

Some artists such as Georges Seurat and Paul-Louis Delance painted the Eiffel Tower even before it was finished. In 1889, the painter Roux represented The Holiday Night at the 1889 Universal Exhibition and Jean Béraud shows it in the background in his work Entrance to the 1889 Exhibition .

Later, several painters will be directly inspired by the building to make some representations that will respond to different artistic currents: Robert Delaunay, Henri Rousseau, Paul Signac, Pierre Bonnard, Maurice Utrillo, Marcel Gromaire, Édouard Vuillard, Albert Marquet, Raoul Dufy, Marc Chagall, or even Henri Rivière.

But the most prolific painter inspired by the Eiffel Tower was Robert Delaunay, who made the tower the central object of some thirty canvases, produced between 1910 and 1925.

Scientific experiments and broadcasting

Gustave Eiffel had thought from the beginning of the project that the tower could be useful from a scientific point of view, so he multiplied the experiments carried out on the monument to provide it with an additional function that could justify its existence. The engineer, out of business since 1893 in response to his involvement in the Panama Canal scandal, financed a part of these experiments.

In 1889, Eleuthère Mascart, the first director of the French Meteorological Central Office created in 1878 (currently Météo-France), had a small observation station installed at the top of the tower, with the authorization of Gustave Eiffel. In October 1898, Eugène Ducretet established the first hertzian telephone connection between the Eiffel Tower and the Panthéon in Paris, four kilometers away. In 1903, Captain Gustave Ferrié, a soldier by profession, tried to establish a wireless telegraph network, but he did not obtain funding from the Army, since at that time optical signals and homing pigeons were preferred, as they were considered more reliable. Despite the situation, Gustave Eiffel financed the captain's project with his money, accepting that he install an antenna on the top of the tower. The experiment was a success and, as we now know, this would later be the technology of the future.

In 1909 a small wind tunnel was built at the foot of the Eiffel Tower, replaced from 1912 by a much larger wind tunnel.

In 1910, clergyman Theodor Wulf measured the radiant energy at the top and bottom of the tower, finding a higher than expected value at the top. This fact led to the discovery of what is known today as cosmic rays.

The Eiffel Tower, therefore, has a scientific potential that deserves to be exploited; something that the authorities realized, who in 1910 decided to extend the concession and exploitation for another seventy years. The tower is very useful as the highest point in the Paris region, since its wireless telegraphy (TSH) station was of great strategic importance during the First World War. Thanks to the Eiffel Tower, several decisive messages are captured, including the "victory radiogram", which thwarted the German attack on the Marne, or those sent by the now famous spy Mata Hari.

The wireless telegraphy network (TSH) for strictly military use installed in the transmitter of the Eiffel Tower, from the 1920s it will also have a civilian use. Since 1921, some radio programs have been broadcast periodically from the Eiffel Tower; Radio Eiffel Tower, well known to Parisians, was officially launched on February 6, 1922.

In 1925, the Eiffel Tower served as the setting for the start of television in France. The technique continues to improve and the emissions continue to be experimental between 1935 and 1939. Television is then broadcast in homes, first in black and white, then in color. In 1959, the installation of a new television broadcasting mast brings the height of the tower to 320.75 meters and transmits to 10 million people. Finally, in 2005, a digital terrestrial television station was installed.

Sports and adventure

Since its origins, the tower has been the scene of multiple sporting feats, especially related to aviation, skydiving and stair climbing, both on foot and with bicycles or motorbikes. In addition, in recent decades, it has been used to organize activities as surprising as ice skating or diving:

Preparation and leap of Franz Reichelt from the Eiffel Tower (1912). |

- 1901: on October 19, the Brazilian Alberto Santos-Dumont, flying in his Directable No. 6, won the 100 000 francs prize offered by Henri Deutsch de la Meurthe for the first person capable of flying back and forth from St. Cloud to the Eiffel Tower in less than half an hour.

- 1905: Le Sport organizes a championship, with a run down the stairs to the first level of the tower, won by Forestier in 3 minutes and 12 seconds. The award: a bicycle.

- 1905: On 18 October, the count of Lambert flies over Paris and the surroundings of the Eiffel Tower for the first time in the history of aviation. His plane is a "Wright" of wood and canvas.

- 1912: On February 4, the Austrian tailor Franz Reichelt died after jumping from the first level of the tower (a height of 57 meters) to demonstrate his parachute design.

- 1923: journalist Pierre Labric, future mayor of Montmartre, went down on a bicycle without authorization from the first level of the tower to the street. The decline received substantial media coverage. The cup won by the "hero" is currently in the basements of the Eiffel Tower.

- 1926: in February, the pilot Leon Collet died trying to pass under the tower with his airplane (the plane was fatally hooked on an antenna).

- 1964: the Guido Magnone and René Desmaison climb the tower to celebrate their 75th anniversary. The event is broadcast by Eurovision.

- 1978: On 26 December, Thierry Sabine began the first Dakar Rally in the Trocadero, at the foot of the Eiffel Tower.

- 1983: Charles Coutard and Joël Descuns go up and down from the Tower on their motocross bikes.

- 1984: On March 31, pilot Robert J. Moriarty flew with his Beechcraft Bonanza aircraft under the tower.

- 1984: two British, Amanda Tucker and Mike MacCarthy, jump in paragliding from the third floor without permission.

- 1987: New Zealander A. J. Hackett made one of the first jumps of puenting from the second floor of the Eiffel Tower, using a special cable that had helped develop. Hackett was arrested by the police.

- 1989: for the centenary of the Eiffel Tower, the equilibrist Philippe Petit "caminated" along a cable through the 700 meters that separate the Palais de Chaillot from the tower.

- 1991: On 27 October, Thierry Devaux, along with the mountain guide Hervé Calvayrac, made a series of acrobatic figures and jumps of puenting from the second floor of the tower. From the side of the Mars Field, Devaux used an electric winch to re-enter the second floor. When the firefighters arrived, he was arrested after the sixth jump.

- 1995: the triathlet Yves Lossouarn bats the record of climbing to the tower by the stairs on foot, with a mark of 8 minutes and 51 seconds. Seventy-five athletes take part in the race, organized by a TV show.

- 1998: Richard Hugues sets the record of climbing the Eiffel Tower down the stairs from the ground floor to the second floor on a mountain bike.

- 2000: In the framework of the World Fire Games, the climbing test of stairs takes place at the Eiffel Tower.

- 2000: Spanish Aitor Sarasua Zumeta bats the record previously established by Richard Hugues of climbing to the tower on a mountain bike.

- 2002: Richard Hugues bats his own record in 1998 of climbing to the tower on his mountain bike.