Egon Schiele

Egon Leo Adolf Schiele, better known as Egon Schiele (Tulln an der Donau, Austria, June 12, 1890-Vienna, Austria, October 31, 1918), was a contemporary Austrian painter and printmaker and a disciple of Gustav Klimt. He was, along with Oskar Kokoschka, the greatest representative of Austrian Expressionism. In his short but eventful life he produced 340 paintings and some 2,800 drawings.

His life was surrounded by an aura of mysticism and very precocious talent. His creative work includes poems and photographic experiments. His particular style placed him among the expressionist movements, especially the Vienna Secession, with a very personal typology.

One of the strongest features in Schiele's painting is the dexterity and firmness of his stroke, which once began without truce, until the end, without any further correction. It seems that the artist continued with his drawing no matter how the model moved or changed place, since the line followed its course carrying its entire emotional dimension.

Egon Schiele's main works are kept in Vienna, distributed between the Österreichische Galerie Belvedere and the Leopold Museum, inaugurated in 2001, which is the one that preserves the largest number of works. Likewise, most of the large collection of his drawings is in the Albertina, also in Vienna.

Early Years

His father Adolf Eugen Schiele (1850-1905) was a stationmaster from northern Germany and his mother Marie (1862-1935)—née Soukoupova—was originally from Krumau (now Český Krumlov) in Bohemia. She had three sisters Elivira (1883-1893), Melanie (1886-1974) and Gertrude (1894-1981), who modeled for Egon from an early age. In 1905 his father died and the young Schiele was sent to live with an uncle, Leopold Czihaczek, who, after having tried in vain to get him to go into the railways, accepted his artistic talent, probably because of the requests for support requested by the Schiele's mother to get the guardian to take care of his support during his studies in Vienna. Already at this time he began to paint, especially self-portraits.

In his early childhood works, the influence of his railway family is evident in his drawings of trains and, later, in some of his landscapes where the shapes seem to emerge from a succession of images observed through the windows of a train. It is known that during his stay in Vienna he often took the train to Bregenz and made the way back with the next one, without stopping to visit the city. Being a guest at the home of the art critic Arthur Roessler, he one day had the occasion to see a scene that he described:

Schiele was sitting in the middle of the room on the naked floor making around him circulate a small and funny toy train driven by a spring... As amazing as the scene of the seriously busy young man with the toy, much more disconcerting was still the fantastic virtuosity with which that player reproduced the multiple tones of the silbido of the steam, the beeps of the signals, the trapping of the wheels, the blows of the rails, the grinding of the shafts and the sharp scream of the steel when stopping... It was amazing everything Schiele was running. With that I could have acted on any variety scenario.

Early Viennese period and analogy with Klimt

In 1906 he entered the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, where he studied drawing and design. In 1909 frustrated by the conservative and closed environment, where the discipline imparted forced him to follow academic paths with the study of life models, compositions and "old-fashioned" clothing, he left the Academy and founded the Neukunstgruppe (New Art Group). along with some classmates.

In 1907 he met the painter Gustav Klimt, whom he always admired and was a very influential teacher for Schiele. From him he adopted his creative principles, in terms of accentuating the drawing of his paintings with thick lines, especially in the representation of the nude body. It was through Klimt that Schiele joined the new current of an artistic community called the Viennese Secession, with its own building for exhibitions made by Joseph Maria Olbrich and whose motto was "To each era its art and to art its freedom". Klimt was the most prominent painter of the group and the first president of the Secession.

Klimt also held him in high esteem, introducing him to some wealthy patrons who ensured him some financial stability as a debutant on the Viennese art scene. During a meeting between the two, Schiele proposed to Klimt an exchange of drawings, to which he agreed, and even bought him a few more. In 1908, Schiele held his first solo exhibition at the Wiener Werkstätte, founded in 1903 by the architect Josef Hoffman and Koloman Moser. In it, he presented works whose theoretical foundation lay in the idea of "total work of art", art was not limited to traditional areas but also to the formal and spiritual that affected daily life. He abandoned the rigid style of the Academy, and turned to expressionism: alongside portraits of friends and self-portraits, he represented the nude through aggressive figurative distortion. If Klimt presented the figure and the ornament as a contrasting relationship where he showed a kind of game between concealment and revelation and where the body became an ornamental sign, in Schiele this game became something more serious, the line is the one that showed the meaning, did not cover or hide, but rather released, it was this line itself that had ornamental values.

In the same year, 1909, Schiele exhibited at the II International Exhibition located in 54 rooms of the Kunstschau, which constituted the largest artistic event that had been seen up to then in Austria. Works so varied were exhibited that they ranged from painting and sculpture, to objects of daily use, floral decoration, scenery and costumes. In the inaugural speech, made by Klimt, he stated: "No sector of life is so meager and insignificant that it does not offer space for artistic aspirations." It was possible to bring together artists from the European avant-garde such as Ernst Barlach, Paul Gauguin, Max Klinger, Pierre Bonnard, Max Lieberman, Henri Matisse, Edvard Munch, Vincent Van Gogh. Also present were the Belgian sculptor Georges Minne who, together with the painter Ferdinand Hodler, were the ones who most influenced Schiele's expressionist art, who exhibited four portraits in a room where Oskar Kokoschka also had works. From what was exhibited in this room came a review in the magazine Neue Freie Presse in which it was said: «You have to enter carefully into a secondary room with supposed decorative paintings by Kokoschka. People are happy to risk a nervous breakdown here."

After an exhibition organized at the Pisko gallery in Vienna with his colleagues from the Neukunstgruppe, in which the expected success was not obtained despite having counted on the visit of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, he left this foundation to dedicate himself "to himself" In a letter addressed to the court counselor Josef Czermak in 1910, in which he informed him of an upcoming individual exhibition at the Miethke Gallery, he concluded the letter with the sentence: «Until March I have passed through Klimt. Today I think I am a completely different person..."

Neulengbach Case

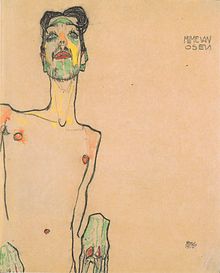

Around 1910 he met set designer Erwin Osen, with whom he rented a studio for the first time in Krumau —his mother's town. There he made nude self-portraits and portraits of his friend Osen on the same theme. This intention to flee Vienna was announced to her brother-in-law Anton Peschka in a letter:

I want to leave Vienna very soon. How awful is life here. All people envy me and conspire against me; old colleagues look at me badly. In Vienna the shadows reign, the city is black and everything is prescriptive... I have to see something new and I want to investigate it, I want to palate dark waters and trees that are broken, see wild winds; I want to look astonished glimpses, as all of them live, listen to young forests of birch and shy leaves, I want to see light and sun and enjoy the blue valleys. Feeling as golden fish shine, seeing how white clouds form, I want to speak with the flowers. See with affection the meadows and the smiling people, meet ancient and dignified churches and small cathedrals, I want to run without stopping by rounded hills and wide plains, I want to kiss the earth and smell the soft and warm flowers of the moss; then I will create with so much beauty: fields of colors...

In 1911 he met 17-year-old Valerie (Wally) Neuzil in Vienna, with whom he became romantically involved and was her model in some of his best works. Schiele and Wally decided to leave to try to get inspiration in the field and moved to Krumau. His way of life shocked the inhabitants of the small town, the free coexistence with his model and that he drew too young girls, so they soon left Krumau and headed for Neulengbach, located to the west of Vienna. The greatest scandal occurred in 1912, when he was accused of corruption of minors due to the age of his young lover, in addition to his habit of having the children who came to his house as models and who, often, he portrayed nude or in positions that seemed obscene. This led to his work being considered pornographic. The conclusion of this fact was the preventive arrest of three weeks in jail and the subsequent sentence of three days in prison together with the burning of one of his drawings, which he had in his study, of a girl dressed in half. body up.

This story was published four years after his death by Arthur Roessler (1922) as an authentic account of the painter. It has been shown that part of the story was Roessler's own invention, since among the text he included thirteen pages written by Schiele in prison (along with many other watercolors and drawings) in which he described himself as a victim with shaved hair and the torture reflected on his face; In many of these drawings there are writings that show the "truth" of him: Art cannot be modern, art is eternal ; That orange was the only light; I feel purified and not punished; Repressing an artist is a crime, it means murdering life in gestation; I will persist with pleasure for art and for my loved ones or The door to the outside among others.

Schiele returned to Vienna and set up his new studio. Thanks to his friend Klimt, he obtained numerous commissions and returned to the top of the Austrian art scene. He came to participate in many international exhibitions, in Budapest, at the Hans Goltz Gallery in Munich and at the "Sonderbund" exhibition in Cologne. His artistic production became very numerous at that time. He met great collectors, including the industrialist August Lederer who asked him to make a portrait of his son Erich, for which he invited him to spend Christmas 1912 at his home in Györ. From there, he sent letters in which he described the luxury of his host's life, the magnificent carriage that was always about to be used, and all the servants dressed in "grey with silver buttons." In 1913 he joined the League of Austrian Artists, participating in numerous exhibitions, such as the international exhibition of "Black and White" in the Secession in Vienna, Hamburg, Stuttgart or Berlin. It was in the latter city that the founder and editor of the magazine Die Aktion noticed him and began to collaborate on articles. In 1916 he devoted a special number of it entirely to the work of Egon Schiele.

Marriage and death

He met Edith and Adele Harms, two bourgeois-class sisters, he invited them for walks and to prove his good intentions, before the austerity of the young women's mother, he was accompanied by his lover Wally, without her suspecting anything of the idea that haunted the painter's mind. This idea was expounded in a letter dated February 1915 to Roessler: "I plan to marry more advantageously, but not to Wall." After courting both sisters, he married Edith on June 17, 1915. Their marriage took place during the First World War and Egon Schiele, because he belonged to what was considered the intellectual elite, was not sent to the front, but to Prague in administrative services. About a year later he was transferred to Vienna with the privilege of being able to use his workshop. As Roessler explains, Schiele proposed to Wally, through a letter from her, that he promised to "undertake a recreational trip with her every summer." Wally rejected this proposal and joined the Red Cross when the First World War began. His death occurred in 1917, without there having been any other meeting with Schiele.

In the year of his marriage, 1915, Schiele painted The Girl and Death, in which he represented a desperate embrace between a couple, on a wrinkled off-white cloth, which represents a bed mortuary, the figures are as if floating on the surface. The painter himself is recognized in the male figure and Wally in the female, the gesture of her embracing the man with her hands and fingers almost separated, while he seems to be pushing her away with his right hand, shows the tension of an approach to at the same time as an insurmountable distance. It was Schiele's farewell to the loss of Wally, caused by her marriage.

In 1918 he successfully participated in the forty-ninth exhibition of the Vienna Secession, for which he designed the exhibition poster and where he sold most of the fifty paintings presented. Also that same year he collaborated in other exhibitions in Zurich, Prague and Dresden. In the autumn of 1918 the 1918 flu pandemic (which caused more than 20 million deaths in Europe) devastated Vienna. Edith, six months pregnant, died on October 28. Three days later, on October 31, 1918, Egon Schiele died of the same illness at the young age of 28. During the brief period that separated his death, Schiele made some sketches of Edith, which are considered his last works. of the. Months before, in February of that year and also due to the pandemic, he had ended the life of his friend and teacher Gustav Klimt.

Features

Its theme assumes a very high emotional tension in sensuality, which becomes erotic obsession, together with the theme of anguishing loneliness. Schiele used a cutting and incisive line to express his own reality and to impetuously show the dramatic physical and moral destruction of the human being. Color takes on an autonomous, non-naturalistic value, proving particularly effective in his many watercolors and in his designs of hallucinated tension.

As in other Austrian painters of the time, such as Alfred Kubin and Oskar Kokoschka, space becomes a kind of void that represents the tragic existential dimension of man, in continuous conflict between life and death and, Above all, the uncertainty. His interest in the body is an artistic fact, which aims to show the strong and sensual part of one of the most important artists of expressionism. Schiele was strongly influenced early on by Gustav Klimt but, around 1910, his painting became a journey of psychological introspection.

Self-portraits

Nearly one hundred self-portraits were made by Schiele, which shows that among the painters of his time he was one of the ones who most observed "his own self", it was always captured in a figurative way, although in the first ones, made between 1905 and 1907, were more naturalistic. Surely this search to demonstrate his being was due to the desire to compensate for the loss of his father's death, through an exhibition and exaltation of his own ego -since his father had always praised his drawings- and being still at the age of After puberty, he tried to assume the role of "man of the house" by intensifying his own pride. From 1910 onwards, he increasingly distorted his figure with extravagant poses and pathetic gestures, which consciously depersonalized or got old Friedrich Stern wrote in November 1912: “Here, too, he presents a self-portrait that is difficult to recognize because the decomposition is too advanced; he believed that he had to represent the young face of him shocked by that decomposition. This is really sad..."

The most outstanding features with which he was represented were the extreme thinness of the figure, the contortions of the body, short and unruly hair and an almost gloomy mimicry. Surely the painter would have read Friedrich Nietzsche, apart from a direct influence, many of his paintings are close to Nietzsche's ideas, such as the one formulated in a chapter of Thus Spoke Zarathustra: «Brother, behind your thoughts and feelings there is a powerful sovereign, an unknown sage called Myself. He lives in your body and he is your body. »

But for the most part he didn't seem so proud of his image, rather showing the pathos of his dilapidated state. Once its function as a classical ideal (the academic nude) and of a social type (the genre of the portrait) had been exhausted, the figure almost reemerged from the psychosexual disorder. The depiction of himself nude became more common, most of the self-portraits have no background at all, just monochrome smooth surfaces which, together with the jagged and angular contour lines of the body, made him achieve a more expressive figure, but further away from the background. natural appearance of the image, which was even more achieved with wide brushstrokes of striking chromaticism. This differentiates his self-portraits from those made by Richard Gerstl, his predecessor who also took self-portraits naked on several occasions.

Human figures

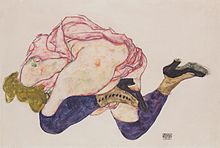

Egon Schiele's artistic attention focused primarily on the human figure, especially the female, which he depicted in a wide and varied range of expressions:

- hard and sharp naked;

- strong, proud and secure women of themselves;

- portraits of deep psychological depth;

- couples intertwined in an erotic hug without love.

Using colors of red, dark brown, pale yellow, and somber blacks, he tried to paint the pathos directly from melancholic landscapes with withered trees, as well as desperate images of grieving mothers and children. They are signs that the unconscious reveals, assuming a much more pronounced emotional depth, characterized by a nervous line, almost neurotic. They take shape on the canvas in a harmonic dissonance that denies aesthetics and breaks the traditional mold. The artist's ego emerges, contorting the matter and leaving the eyes bulging and the hands twisted. The hands are where the lines seem to denounce the pain, the suffering, the sadness of a drifting soul. Schiele described the intricacies of his mind, the dark torment and painful trauma caused by the untimely loss of his father in 1905, an event that indelibly marked his relationship with women and eroticism.

Terribly provocative female bodies appear on his canvases, with often absurd poses, to confuse spatiality. Heinrich Benesch described her way of working:

The beauty Schiele gives us in shape and color, never existed before. His drawing was something unique. The security of his hand was almost infallible. When I was drawing I used to sit on a lower side, the drawing board with the leaves on the knees supporting the right hand on the base. But I also saw him draw in another way, standing in front of the model supporting the right foot on the sidewalk. He held the drawing board on the right knee and held it with his left hand on the upper edge. Then he had the pencil, pulse, perpendicular to the blade and drew his lines, so to speak, from the joint of the humerus.

The artist presented an existential and psychological erotic tension to spread a message of social criticism against the falsehood of the bourgeoisie. More than a liberation of the self, his art shows an internal conflict of the individual subject that confronts him in relation to the authorities, academic and governmental institutions. In some of his letters addressed to his brother-in-law Leopold Czihaczek and to the collector Oskar Reichel, a solipsistic "philosophy of life" appears in Schiele, in which he expressed opinions against the attacks of the "philistines":

...the artists will always live. I think the great painters always painted figures... I paint the light that comes from the bodies.—The work of erotic art also has holiness!— A unique work of "living" art is sufficient to achieve the immortality of the artist...—My paintings should be placed in buildings similar to temples.

On a rough and rugged surface, Schiele showed, without false modesty, an eroticism devoid of morality and sad, where the protagonists are girls with childish faces and a deliberately impudent attitude. She represented them in the most diverse variations, seen from above or in profile and with strange positions and extravagant movements. Benesch noted that he sometimes painted her models from a ladder, positioned above them.

Schiele was a skilled draftsman, with a clear, fast and hard line, without a doubt, he did not give space to the decorative or aesthetic appreciation of his paintings or drawings. His works all have a strong and violent impact on the viewer, who almost assumes the position of a psychoanalytic interpreter; they exude the desire for rebellion and provocation as existential anguish. Schiele searched, in the anguished figures without reference to the historical and social context, the "repressed instincts", he explored exhibitionism and voyeurism, towards an affective state that can reach the pathological.

He worked, in a constant and always present sense, the dramatic character and a vision of reality suffered and meditated on his interior. Schiele's art allows, then, to lose oneself in the existential infinity and finds oneself face to face with the meaning of life, which defies orders and stops in the emotional magma of a stain of color. One of the sources of inspiration came from the experiences of mental patients that his friend Erwin Osen had made on behalf of Dr. Kronfeld: drawings of patients from the local Steinhof mental hospital. Osen was a character with an artificial mimicry that Schiele, in the portraits he made of him, managed to convey. It is also possible to establish a direct relationship, comparing some drawings with those made by Dr. Paul Richer, assistant to the neurologist Jean Martin Charcot, that constituted a catalog of characteristic features of pathological phases. The painter was able to adopt these typologies in some of his models, including himself, since they have the striking movements that they present static or in a convulsive attitude, a certain resemblance to Charcot's "mannequins". The result of the research by Charcot and Richer, who observed that his studies partly reappeared in historical paintings and drawings, they edited it in their work Les démoniaques dans l'art (1887).

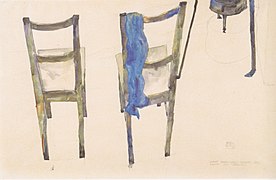

Landscapes and others

Looking around him, Schiele couldn't help but feel fascinated by Van Gogh and his personal, heavy and strong chromatic charisma. He paid homage to him in The Artist's Room in Neulengbach, inspired by The Bedroom in Arles (1888) by the Dutch painter, as he also reinterpreted Sunflowers, in a version with an opaque brown color, where the petals lose consistency and acquire the tragic truth of decadence. The very elongated format and the mimicry of the large leaves make his sunflower a reflection of almost human feelings.

In the final phase of his life, the line becomes more nervous, he reaches maximum freedom of expression creating many landscapes, in the Four Trees, from the year 1917, he already uses warm colors and the background it becomes an environment with violent emotions. He shows in this painting, some horizontal and vertical lines in his composition and a tree with fallen leaves, among those that are full of them, he achieves an autumnal effect of melancholy.

The author described in a 1913 letter about painting from nature:

I also do studies, but I believe and know that the copy of nature is of no importance to me, because I paint better from memories, as a view of the landscape. I now observe above all the bodily movements of the mountains, water, trees and flowers. Everywhere they remind one of movements similar to those of the human body, similar feelings of joy and sorrow on the plants.

The artist's urban landscapes changed as did his depictions of nature. The landscapes of his youth were in a traditional style, among which are those made in Klosterneuburg. In 1910 he painted two paintings entitled The Dead City, inspired by the novel Brugues-la-morte, translated into German, by the Belgian writer Georges Rodengach (1892).. He renounced the description of the environment or a topography and focused on the construction of the houses, many of them from a bird's eye view as in the Krumau Landscape (1916) or in Suburb house with hanging clothes (1917), where he expressed an intimate vision that presents a simplicity with a picturesque appearance. This same way of making, in the drawings, brings him closer to a more illustrative appearance, in short, in his landscapes there are no chimneys or testimonies of any kind of industrial technique, just as for the poet Georg Trakl the "big city did not produce no spiritual landscape". The painter and writer Albert Paris Gütersloh, a friend of Schiele's, was the first who, relying on the "bird's eye view", described in a 1911 essay: "He (Egon Schiele) calls dead a city that sees in perspective, from top to bottom. Because any city would be if he looked at it that way. The double meaning of the bird's eye view is unconsciously understood. The title is equivalent to the idea of the painting it designates."

The last major painting by Schiele was one entitled The Family (1918). It is quite unusual in realism for the painter and documents his biographical situation —at that time his wife Edith was expecting a child— and his development in art. It presents a group of nudes, the man, in whom it is easy to recognize the author himself, is seated on a sofa, in front of him, sitting on the floor, appears the figure of a woman with a small child between her legs wrapped in a blanket. The illuminated bodies of the adult characters and the child's face stand out against the dark color of the background, the chromatic tones serve in this painting to highlight the body volumes, they are not thick lines filled with color, like his previous paintings. It is actually a pictorial work that shows a less aggressive language than the one previously used by Schiele. Despite its theme, the painting shows a melancholy without drastic expressiveness, the gazes of the man and the woman are lost in their thoughts, with this, the author breaks the composition of the group united in an almost circular way.

Literary work

- Schiele, Egon: Egon Schiele in prison. Vigo, Maldoror editions, 2004. Translation: Jorge Segovia. ISBN 84-933639-1-X PDF with full book and drawings

- Schiele, Egon: I, eternal child (Poems). Vigo, Maldoror editions, 2005. Translation: Jorge Segovia.

Contenido relacionado

Sandro botticelli

Braveheart

Bejar