Economic history

The economic history is the branch of historiography that studies the economy of the past, as well as the branch of economics that studies the economic facts and structures of the past.

Economic history should not be confused with the history of economic thought, a discipline that studies the history of schools of economic thought. Economic history is concerned with describing the evolution of the economic systems that have served the human species to ensure its survival and multiply its population. Since the social sciences are not susceptible to experimentation in a laboratory, past situations and the data collected on these should be used when developing falsifiable hypotheses.

According to the particular methodologies and approaches of each school of economic historians, its purpose is either to understand the persistence of long-term structures (Fernand Braudel's concept), their gradual transformations in the great historical transitions (transition from feudalism to capitalism), its behavior at the level of the conjuncture (secular crises such as the crisis of the 14th century or the crisis of the 17th century; shorter cycles such as the 1929 crisis or the 1973 crisis); or, from another point of view, explain how changes in the social structure and markets have contributed to economic development in the long term. A recent trend in economic history is the so-called cliometrics (referring to Clio the muse of history) applies the techniques of statistical and econometric analysis to historical data and facts, its main representatives being Robert Fogel and Douglass North. Historiography influenced by the French Annales School or Anglo-Saxon historiography close to historical materialism of Marxist origin usually goes hand in hand with social history, in what can be considered more of an approach than a genre, called economic and social history.

The objective is to understand what have been the great movements of the world economy that have brought us to the current situation, characterized by life expectancy and consumption levels incomparably higher than those of previous civilizations, but which continues to have many pending challenges. Among them, the most important is to extend the benefits of economic progress to the billions of people who are still outside of it.

Paleolithic Economics

Due to the lack of written sources from the pre-agricultural period, idealizations cannot be made about how men lived in those times. However, certain generalizations can be made from Aboriginal groups that have been studied by modern anthropologists and historians.

"It is certain that the vast majority of people lived in small gangs or bands that numbered in all several tens, or at most several hundred people. Perhaps in periods of crisis they approached neighboring gangs to hunt together. Trade was mostly limited to prestigious objects. There is no evidence that people traded basic goods like fruit and meat. The sapiens population was scattered over vast territories. Most gang cultures lived as nomads, traveling from place to place in search of food. In general they moved through the same known territory. Sometimes gangs would leave their territory and explore new lands, whether due to natural disasters, violent conflict, population pressures, or the initiative of a charismatic boss. These displacements were the engine of human expansion throughout the world."

Because of the healthy and varied diet, relatively short work week, and rarity of infectious diseases, American anthropologist Marshall Sahlins has defined pre-agricultural hunter-gatherer societies as "the original affluent societies." However, per capita consumption levels were much lower than today, schooling was nil and maternal and child mortality was high.

The Neolithic Revolution

The Neolithic revolution, along with the industrial revolution, has been the historical-economic process that has had the greatest impact on the organization of human societies and modes of production. Both revolutions involved a demographic explosion of human societies.

The Paleolithic economy was largely based on non-intensifiable modes of food production such as hunting, gathering, and fishing. On the contrary, the Neolithic economy led to a broader development of agriculture and livestock, which were intensifiable modes of production, that is, if more hours of work were dedicated to these activities, production could be increased, compared to hunting and gathering that they were hardly intensifiable, in addition to being modes vulnerable to overexploitation.

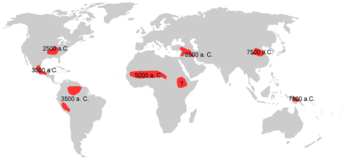

Intensive agriculture appeared independently in various regions of the planet. It seems that the only continent where agriculture was an imported development was Europe where agriculture spread from migrations or expansions of peoples from the Near East.

The intensification of agriculture allowed for the first time the existence of surpluses, which allowed the existence of permanent settlements, the demographic explosion, labor specialization and consequently labor stratification. The diversity of social roles and the division of labor led to the appearance of serfdom, wars, the existence of social classes, in turn the increase in the number of people who formed a community led to the need to coordinate social action and ultimately led to the emergence of city-states and an administrative class (where writing and other more complex cultural developments often developed). If the primitive civilization only knew how to survive, the agricultural-pastoral civilization soon revealed a taste for novelties.

Ancient Economics

The economy of the ancient world was not capitalist, it was rather slave-owning. The empires of Mesopotamia, Egypt, Persia, India, China, Greece and Rome stand out. The social organization associated with its economy was characterized by:

- A hierarchical system of immutable social classes with little or no social mobility, based on traditional units such as family clans, castes or social orders.

- An agrarian system of low or no economic growth because there was no investment or savings. Wealth did not become capital, because it did not reinvest systematically.

- Dimension of the reduced market, and limited to the marketing of surpluses and products of first necessity, mainly.

- In its last phase, the economy of the ancient world was already monetarized and the barter was gradually disappearing.

The Roman Empire was based on a mixed system, made up of the typical tributary empire model and a slave model with forced labor.

In China and India with some differences it seems that a similar system existed although with peculiar regional developments. It is important to note that already during this period there were trade routes that linked the West and the East both through the Silk Road and by sea through the Red Sea. However, products traded over long distances were mainly limited to luxury products and evidently non-perishables.

Medieval economy

Europe

In Western Europe, the Roman economic system evolved into a basically agricultural society, in which land was the primary source of wealth and power. The political translation of this economic fact is the system commonly known as feudalism, which presented regional variations, and which was never uniform throughout Europe. This system had growth rates close to zero, and wages were highly dependent on the amount of labor available. Thus the great black plague of the mid-century XIV that killed 30% of the European population, produced a dizzying increase in wages in subsequent generations.

Chinese

During the Middle Ages, China was in many ways technologically superior to Europe and had an economy that was larger and involved larger exchange networks than existed in Europe. During the Song dynasty the use of paper money became widespread, which contributed to the economy during the beginning of the "Chinese industrial revolution". Historian Robert Hartwell estimated that per capita production of cast iron in China increased sixfold between 806 and 1078. Many inventions that were of crucial importance in early modern Europe originated in China: gunpowder, paper coin, cannon, compass, printing press, etc. (see Annex: Chinese inventions), however, those who gave a greater impetus to these inventions were the European empires. Adam Smith wrote in 1776: 'China has long been the most fertile, best cultivated, most industrious, and most populous country in the world. But it has also been in a steady state for a long time."

Modern and contemporary economy

Certain economic developments shortly before the discovery of America and the introduction of certain technical innovations, some of them imported from China, marked the beginning of European expansion in America, which would later also spread to Oceania, parts of Asia and Africa. This eminently military but also economic and cultural expansion led to a world predominance of European powers and others that emerged from European colonization (such as the United States or Australia).

Mercantilism and the origins of capitalism

The European economy of the XVI centuries, XVII and the first half of the XVIII, an economic policy characterized by a great interventionism. A strong control of the currency was promoted, state regulation of the economy was expanded, the unification of the internal market, and own production was stimulated, controlling natural resources and markets. Protectionism was widely practiced, protecting local production from foreign competition, subsidizing private companies, and imposing heavy tariffs on foreign products. In addition, an increase in the money supply was sought -through the prohibition of exporting precious metals and inflationary coinage-, always with a view to multiplying tax revenues. These actions had as their ultimate goal the formation of nation-states as strong as possible. Although this doctrine known as mercantilism is not an entirely coherent set of economic recommendations, most economic specialists of the time adhered to a greater or lesser extent to most of these measures. These policies occurred in a general context of increasing population income in European nations, in which extra-economic factors also intervened. During this period, both due to the increase in metals in circulation from America and due to inflationary policies, the price revolution took place between the centuries XV and XVI.

Though during the 18th century these policies were progressively discarded, Adam Smith extensively criticized these doctrines in The Wealth of nations and instead widely promoted economic liberalism.

European industrialization

The concept of "industrial revolution" refers to the birth and early development of modern industry in England (later in the rest of Europe and the world) from the extensive use of mechanical machinery, the introduction of new sources of energy (hydraulic, coal, gas and oil) and the organization of the factory production system.

This made it possible to perform tasks that until then had been done much more slowly and laboriously with human or animal energy, or not done at all. The introduction of the steam engine in mining, manufacturing, and transportation produced impressive results. The changes were not only “industrial”, but mainly social.

Why did the industrial revolution happen in England? is a question that historians continually ask themselves. The reasons are diverse, but they stand out: scientific progress and technological applications made, an increasingly thriving bourgeoisie, the consolidation of a legal system that guaranteed private property rights, political thinkers who advocated greater economic freedom and the Protestant ethic. pushed for enrichment.

First globalization (1870-1914)

The consolidation of national markets in almost the entire globe and their growing interconnection as a result of free trade take place. Internal customs within states disappear in almost all of Europe and Asia. The first international banks and insurance houses and the first integrated global textile and iron and steel industries appear. The first massive migrations between Europe and America take place, leading to the emergence of a global labor market. The first non-Western power emerged, Japan, which faced the Russian empire successfully in 1905. The first globalization had its catalyst in the telegraph and its cultural symbol in the optimism of progress and free trade, the universal exhibitions, the concert of nations and Verne's novels. It ends with the First World War, which if to a large extent is global, affecting the economies of all regions, including neutral South America, is because it is the first to occur within the framework of a minimally structured world market.

The Great Depression and the Interwar Period (1914-1945)

Unlike Europe, the United States emerged from the war stronger than ever. Only in economic terms had it gone from being a debtor to a creditor and had obtained a leadership position worldwide in new markets. The "happy twenties" in a time of continuous growth and increasing speculation. During the speculative rise, many people with modest incomes bought stocks on credit. In the midst of the furor, a financial bubble was created that finally burst on October 24, 1929 - "Black Thursday" -. Americans who had invested in Europe stopped doing so and sold their assets there to repatriate the funds. Thus the crisis spread to Europe and other parts of the world. Some historians point out that this was one of the reasons why the fascist leaders -Hitler and Mussolini- were able to rise to power in Europe.

The Golden Age of Capitalism and Communism (1945-1973)

Shortly before the end of World War II, the Bretton Woods agreements of 1944 were an attempt to establish rules for trade and financial relations among the world's most industrialized countries. Within the agreements reached, the creation of the World Bank and the IMF and the use of the dollar as international currency were decided. These organizations became operational in 1946. These agreements tried to put an end to the protectionism of the period 1914-1945, which began in 1914 with the First World War. It was considered that in order to reach peace there had to be a free trade policy, where relations with the outside world would be established. For various reasons, economic growth in capitalist countries under these rules and institutions was stable and sustained in the period 1945-1973.

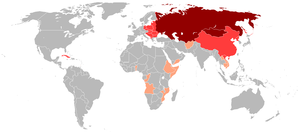

On the other hand, at that time the countries where the socialist path was practiced also experienced vertiginous economic growth rates. In fact, during the period 1950-1965 the Soviet Union and other socialist countries experienced much higher growth rates than the average experienced by the capitalist countries of Western Europe and North America.

Other countries such as South Korea or Japan opted for a third way that could be called state capitalism or economy with strong state intervention, with the aim of achieving a broad and rapid industrialization of these countries.

Second globalization and economic crises (1973-2010)

From 1973 to the present, the global growth rate has been considerably lower than in the period 1945-1973. The 1973 oil crisis had a devastating impact on oil prices, leading to a major economic crisis in the most oil-dependent Western countries. Starting in the late 1970s, in various countries, Keynesian policies were largely put into a corner by numerous governments, for political reasons or because some economists considered that they did not provide adequate responses in the new economic situation. In large part, the abandonment of developmentalist economic policies were accompanied by a boom in neoliberal policies aimed at deregulating the economy, reducing the size of the public sector in the economy, and privatizing numerous industries.

During this period, the secondary or industrial sector decreased as a percentage of GDP in many countries, and at the expense of the tertiary sector (service sector), and the development of ICT began to play a prominent role in the economy of many Western countries.

However, this period was much less stable with respect to growth and was subject to numerous regional economic crises such as the Latin American debt crisis during the 1980s, the European crisis of the 1990s (it was especially severe in Sweden and Finland), the crisis, the Asian financial crisis of 1997 and other crises that are even more localized such as those of Japan (1986-2003), Mexico (1994), Russia (1998) or Argentina (1999-2002). All of them a prelude to the great economic crisis of 2008-2013.

Contenido relacionado

Soviet Union flag

History of Christianity during the Middle Ages

Act of Independence of the Mexican Empire