Dutch language

The Dutch language (self-glotonous: Nederlands; pronounced/ıne felt by reference(![]() listen)) is a language that belongs to the German family, which in turn is a member of the Indo-European family. In Spanish-speaking countries it is commonly known as Dutch, term to a certain extent accepted by the SAR, even if it is the name of one of the Dutch dialects. It is part of the Western Germanic group, related to the German bass. It is the mother tongue of more than 25 000 people in the world and the third Germanic language with more native speakers, after English and German.

listen)) is a language that belongs to the German family, which in turn is a member of the Indo-European family. In Spanish-speaking countries it is commonly known as Dutch, term to a certain extent accepted by the SAR, even if it is the name of one of the Dutch dialects. It is part of the Western Germanic group, related to the German bass. It is the mother tongue of more than 25 000 people in the world and the third Germanic language with more native speakers, after English and German.

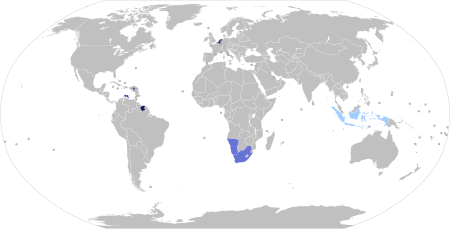

- It is an official language in the Kingdom of the Netherlands composed of the Netherlands (in the Frisian region it is also official), the islands previously called the Netherlands Antilles of Curacao, San Martín, Aruba, Bonaire, Saba and San Eustaquio, in Belgium (in particular in the regions of Flanders and Brussels) and in Suriname. It is also one of the official languages of the European Union and the Union of South American Nations.

- Unofficial, he is also employed as a mother tongue in parts of the Lower Rhine region of Germany and in northern France (about 60 000 speakers approx.). Because of colonization and emigration, it is also spoken in Canada (about 160 000), in the United States (about 150 000), in New Zealand (about 29 000) and in some parts of Indonesia (35 000 students per year), where it was the language used in the Dutch colonial public administration.

Historical, social and cultural aspects

Varieties of the language

The name of the language in Dutch is nederlands. The use of the word Dutch in official documents is recommended. Due to the turbulent history of the Netherlands and Belgium, as well as the Dutch language, the names that other peoples have chosen to refer to it vary more than for other languages.

Dutch

In Spanish, the word neerlandés derives from the French néerlandais, in turn derived from the word Nederlands, which in the Dutch language is the adjective from Nederland, whose meaning is "Low Land" or "Low Country".

Dutch

Strictly speaking, "Dutch" is the dialect of Dutch spoken in the regions of North Holland and South Holland.

In common speech, metonymically, the language is called “Dutch” regardless of geographical boundaries, and in fact is used much more frequently than “Dutch” . It should not be considered an error, since in Spanish it is correct to use this word to refer to the Dutch language, as it is included in the Dictionary of the Royal Academy; however, in academic or official environments, it is convenient to avoid ambiguity and stick to the term official. In many languages, Dutch is the only term that works for this language.

Flamenco

The political separation between the Dutch-speaking provinces meant that in each area the language underwent an evolution with many idiosyncratic features. The term flamenco was used somewhat informally to distinguish the peculiarities of the south. In the first years of autonomy of Flanders within Belgium, Flemish (vlaams) was used to refer to the language of this region, but soon after this word was completely eliminated from the legislation to use only the term Dutch (Nederlands). The term "Flemish" is still in use today to refer to the set of Flemish dialects.

Limburgish

Limburgish is a set of regional speech closely related to modern Dutch, as it is also a descendant of Old East Franconian. Some linguists classify Limburgish as a separate language, while others consider that Standard Dutch, Flemish, Limburgish and Afrikaans can be considered as divergent varieties of the same language with a high degree of mutual intelligibility.

Afrikaans

Afrikaans, spoken in South Africa and Namibia, is a West Germanic variety closely related to Standard Dutch in that both derive from Middle Dutch. Afrikaans is considered a different language because of the growing differences with Dutch that appeared from the 17th century; however, they still have a high degree of intelligibility.

Examples in other languages

The English word “Dutch” comes from “Diets”, the old Germanic word for the language of the “Diet”, the “ people" as opposed to the "cultured" Latin-speaking elites. The same root gave rise to the word “Deutsch”, which in the German language means “German”.

Regional dialects

A quick classification that is usually made is to reduce their dialects to two, Dutch* in the north and Flemish* in the south, and this is the classification that the RAE dictionary. In a more detailed classification we would have eight main variants that would actually be groups of more local dialects.

- ♪ The use of the terms is clarified in the “Name of the Language” section Dutch and Flamenco.

Historically, varieties of Dutch have been part of a dialect continuum that also includes varieties more closely related to Standard (High) German and Low German.

The maps show the distribution of Dutch dialects, ignoring some peculiarities that occur in some cities.

Low Saxon Dutch, Zeelandic and Limburgish are also shown as dialects, although it is debatable whether this is a dialect or a separate language, since in West Germanic languages it is very problematic to establish a clear border between dialect and language.

A | South-West Group |

|

|

B | Northwest Group (Dutch) |

|

|

C | North-Eastern Group (under Dutch sajón) |

|

|

D | Central-septentarional Group |

- 19. Utrechts-Alblasserwaards

E | Central-central |

|

|

F | South-Eastern Group |

- 24. Limburgs (bourgeois)

G | Suriname |

- 25. Suriname-Nederlands (Nerlands of Suriname)

H | Netherlands Antilles and Aruba |

- 26. Antilliaans-Nederlands (Dutch Antilles)

| Area without own dialect |

- FL. La provincia de Flevoland was created between 1940 and 1968 on the basis of land won to the sea, and its inhabitants come from various regions so that a dialect has not been created in it, except the ancient island of Urk to the north of the province (the small area of different color united by a line to the area marked with the 17)

- ♪ The dialects marked with an asterisk have an important substrate of the Western Frisian language.

Features of Dutch

Dutch is notable for its tendency to form long and sometimes very complicated compound names, being similar to German and Scandinavian languages.

Like most Germanic languages, it has a syllabic structure that allows for fairly complex consonant clusters. Dutch is often noted for its prominent use of velar fricatives (sometimes as a source of amusement or even satire).

It has three genders: masculine, feminine and neuter, however, given the few grammatical differences between masculine and feminine, in practice they seem to be reduced to only two: common and neuter, which is similar to the gender system of most continental Scandinavian languages.

Regulation

The body that regulates the language is the Nederlandse Taalunie (Dutch Language Union), created in 1986 with the aim of establishing the common language standard for the Netherlands and Belgium. Later in 2004 Suriname joined.

The official standard is known as Standaardnederlands (Standard Dutch), although it is also called Algemeen Nederlands or AN (General Dutch), a term derived from the old ABN (Algemeen Beschaafd Nederlands) which fell into disuse as it was considered an elitist term.

Neighboring languages

The vocabulary of the Dutch language maintains a predominantly Germanic origin, which brings it considerably closer to German than to English, since the latter has been heavily influenced by French. The Dutch share many features with the German, but with a less complicated morphology caused by deflection. The Dutch consonantal system, not having undergone the consonantal mutation of High German, on the contrary, has more in common with the Anglo-Frisian and Scandinavian languages.

The fact that Dutch did not experience the sound changes may be the reason why some people loosely say that Dutch is a bridge or even a mix between English and German.

Dutch is closely linked to Afrikaans (13.5 million speakers), a Germanic language spoken mainly in South Africa and Namibia. Afrikaans and Dutch have different dictionaries and rules, but are mutually intelligible. In Aruba, Bonaire and Curaçao, Papiamento is spoken, a creole language derived from, among others, Portuguese, Spanish, English and Dutch. Sranan Tongo is spoken in Suriname, a creole language derived from, among others, English and Dutch.

Spelling

Dutch is a language whose spelling has been reformed as the language has evolved, unlike what happened with, for example, English or French, which allows the correspondence between how it is written and how it is read a word is immediate. It uses the Latin alphabet and reserves some letter combinations to represent specific sounds of the language and that are shown below, together with the representation in the International Phonetic Alphabet:

Vowels

| Symbol | Example | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| AFI | AFI | Orthography | Spanish |

| | b・t | bad | bathroom |

| a | za | zaad | seed |

| ‐ | b | bed | bed |

| e | d | beet | bite |

| ♫ | dø | of | article |

| . | kp | kip | chicken |

| i | bit | biet | Remolacha |

| btt | bot | bone | |

| o | # | boot | Boat |

| ø | ## | neus | nose |

| u | | hoed | ha. |

| t | hut | cottage | |

| and | fyt | fuut | zambullidor |

| ‐ | ▪ | ei, wijn | egg, wine |

| œy | œy | ui | onion |

| 🙂 | z brushut, f | zout, faun | salt, fauno |

Consonants

| Symbol | Example | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| AFI | AFI | Orthography | Spanish |

| p | p | pen | pen |

| b | bit | biet | Remolacha |

| t | tak | tak | branch |

| d | dѕk | dak | roof |

| k | Kurt | kat | cat |

| g | go | goal | Gol |

| m | m | men | human being |

| n | - | nek | nuca |

| Русский | ▪ | eng | Dark |

| f | fits | fiets | bicycle |

| v | a | oven | Oven |

| s | skk | sok | sock |

| z | ze | zeep | soap |

| MIN | ・a devoted | sjaal | chal |

| ♫ | Русский | jury | jury |

| (North) | ・xt | acht | eight |

| ç (South) | | acht | eight |

| (North) | | gaan | go |

| ) (South) | a devoted | gaan | go |

| r | r› | rat | rat |

| ▪ | | hoed | ha. |

| ️ | wang | cheek | |

| j | j› | jas | coat |

| l | l Staffing | land | land/country |

| | Heel | whole | |

| . | b·liques | beamen | confirm |

Dutch makes use of the umlaut to indicate when a word (usually originating from another language) has a certain combination that should not be interpreted as a digraph of a sound but as a combination of two letters. For example, the combination ie represents the long i [i] (equivalent to the Spanish i). When in a word the sound i must be followed by the sound e, an umlaut is written over the e to break the digraph, as for example in the word Italië (Italy), or in efficiënt (efficient). Other examples would be: politeïsme (polytheism), poëzie (poetry) or altr uïsme (altruism). It also appears above the o and u in words such as reünie (meeting) and coöperatie (cooperative).

We should mention some obsolete spelling, but that can be seen in some surnames or place names:

- ae [a] that according to the current spelling should be written aa.

- ? [engine], [æi] that should be written ij. It must not be confused with andthat in Dutch does not exist and appears only in words of foreign origin as systeem, coyote or baby. Despite that, ij is sometimes written as andwhich is considered an incorrect graph.

The letter ij is subject to some debate as to whether it is one letter or two. Most dictionaries order it as i followed by j and telephone listings usually order it between x and z to make it easier to find surnames that use the spelling ÿ. According to the standard, it is a letter that can be typed with two characters (i + j ), although there is a symbol in Unicode and in the Extended-Latin character set that with a character presents ij or IJ as a complete symbol (codes x0133 and x0132). As you can see, the capital letter should be written IJ, never Ij. On billboards where it appears written vertically, the letter IJ must occupy a single line, with the I and J contiguous, without being the I over the J.

A spelling oddity in Dutch is the way in which short and long vowels are distinguished. The norm is linked to the syllabic division, which is why it is especially difficult for those who are new to the language, although it is easier for the speakers themselves than, for example, the norm for the use of accents in Spanish.

In general, and ignoring both the exceptions and the cases of compound words, with affixes and some other singularities:

- When between two syllables there is only one consonant, the consonant always begins the second syllable: Heu-vel (colina) au-to (cart/cart).

- If there are two or more consonants followed, the first consonant finishes a syllable and the next syllable begins: kap-per (sighs) As-You-rië (Asturias).

- A short vowel in a syllable appears always written with a single letter between consonants: zon (sol), stank (hedor).

- A long vowel in a syllable appears written:

- with a letter if the syllable is not closed by a consonant: zo (so, like this), ka-♪ (room).

- with two letters if the syllable goes between consonants: zoo (son) deur (door) vuur-pot (brasero).

- NOTE: The script (-) appears in the above examples only to indicate the silobical division. The words shown are written without the script.

The problem arises when conjugating verbs or forming plurals, where it may be necessary to double vowels or consonants to maintain vowel length:

- man (man) Mannen (men)

- La a in "man" is short as it is between two consonants. If added simply - to form the plural the division of the syllables would remain «Ma-nen»; now the a the syllable is finished, so the consonant must be doubled to stay written like a short: Mannen (man-nen)

- Maan (luna) Manen (moons)

- La a in “maan” is long as it always appears folded (aa), by adding - to form the plural the syllables that would remain are «Maa-nen»; now as the a finishing the syllable is no longer necessary to appear bent to indicate that it is a long vowel, then remaining Manen (ma-nen).

Another Dutch spelling quirk occurs with words ending in -ee. When adding suffixes with vowels, an umlaut should be placed over the added vowel as in the following example:

- idee (idea) ideeën (ideas)

- La e long at the end of a word should always be written with double e (ee); it is a singularity of the vowel e, that unlike the rest of the vowels, if written alone is pronounced as a and mute instead of as a long [e]. By forming the plural by adding - A triplewhich, although non-existent in the language, the rule indicates that e added should wear diaes break the union with the ee previous.

Dutch Grammar

Nouns

Dutch has a knack for creating long nouns by compounding, such as "drinkwatervoorziening" (drinking water supply), "arbeidsongeschiktheidsverzekering" (incapacity for work insurance) or already creating words that, although correct, are not included in the dictionary, we have «koortsmeetsysteemstrook» (band of the fever measurement system), which is also a palindrome.

The plural exists in various forms, but there are no general rules about using them because it is specific to each noun. The two most common plural forms are -en: trein (train); treinen (trains), and the -s: appel (apple); appels (apples). Words ending in a silent e usually allow both possibilities interchangeably: hoogte (height); hoogten (missing an e), hoogtes. In words ending in a long vowel, the pluralic -s is preceded by an apostrophe, thus keeping the syllable open: radio, radio's. The same happens with acronyms, to clarify that the plural is not part of it: gsm (mobile phone); gsm's (mobile). Sometimes other letters are added, as for example in kind (child); kind-er-en. Vowel changes occur in the word stem: schip (boat); schepen (boats), as well as consonant changes: huis (house), hui zen (houses). There are words with more than one plural, where the various forms designate the different meanings of homophonic words: pad (path or toad); paden (paths) or padden (toads). Besides, there are completely irregular plurals: koopman (merchant); kooplui, kooplieden (traders). This last example is similar to Spanish: persona; people.

Dutch nouns have three genders, masculine, feminine and neuter. Gender is clear when it is tied to sex: vrouw (woman) is feminine and man (hombre) is masculine, but as in Spanish, it is sometimes quite arbitrary: medicatie (medication) is feminine, mond (mouth) is masculine and huis (house) is neuter.

When it comes to using masculine or feminine words, there is practically no grammatical difference, and only the neuter has clear differences, as can be seen below when talking about the articles. In fact, in Dutch dictionaries do not usually indicate the gender of the word but rather the article that accompanies it, frequently speaking of het-woorden and de-woorden (words with het and words with de).

Articles

Articles can be determined and indeterminate, of neutral or common gender (masculine and feminine).

- Singular Article: of (male and female) / het (neuter)

- Ik koop de plant / Ik koop het boek

- «I buy the plant»/ «compromise the book»

- Determined Plural Article: of (male, female and neutral)

- Ik koop de planten / Ik koop de boeken

- «I buy plants»/ «comprode books»

- Indeterminate Singular Article: een (male, female and neutral)

- Ik koop een plant / Ik koop een boek

- «I buy a plant»/ «I buy a book»

- Indeterminate Plural Article: It does not exist. It is not replaced by another particle

- Ik koop planten / Ik koop boeken

- «I buy [one] plants»/ «compro [one] books»

Adjectives

Adjectives have a small declension, consisting of adding or not adding a final -e, and must agree with the noun.

Depending on the function performed by the adjective we have:

- As a preaching or attribute (after a verb) the adjective is always used without adding - Hey.:

- De plant is Mooi (The plant is pretty) / Het boek is Mooi (The book is beautiful)

- Modifying a noun (in Dutch always prior to the noun) is added - Hey. in almost all cases:

- If the noun is plural, it is always added - Hey.:

- Ik hou van Mooie planten (I like pretty plants)

- Ik lees Mooie boeken (Leo libros prettys)

- If the noun is unique, it depends on the gender and whether or not it is determined:

- If it is a male or female noun, it is always added - Hey.:

- Ik water Mooie plant (I water the pretty plant)

- Ik wil een Mooie plant kopen (I want to buy a nice plant)

- If it is an undetermined singular neutral noun, it is not added - Hey.:

- Ik wil een Mooi boek kopen (I want to buy a nice book)

- If it is a particular neutral noun, it is added - Hey.:

- Het Mooie boek was duur (The pretty book was expensive)

- Dit Mooie boek was interessant (This beautiful book was interesting)

- Exceptions: Some adjectives never add - Hey.:

- adjectives completed in -: open (open).

- completed in - Yeah.: premium (excellent).

- some special cases: oranje (naranja), plastic (plastic), etc.

The comparative is formed by adding -er: mooier (prettier)

The superlative is formed by adding -ste: mooiste (the most beautiful thing)

Pronouns

The personal pronouns are:

- Ik (me).

- Je/jij (tu).

- U (you).

- Hij (he).

- Ze/zij (ella).

- Het (the-neutro-).

- We/wij (we).

- Jullie.

- Ze/zij (them).

Some pronouns are characterized by usually having two forms, one unstressed and the other tonic, using the second when you want to emphasize:

- Je/jij (tu).

- Ze/zij (ella).

- We/wij (we).

- Ze/zij (them).

Examples:

- We waren op tijd (We arrived at the time).

- Wij waren op tijd (We arrived at the time).

- By emphasizing us., we would be distinguishing ourselves from others, implying that others were late, for example.

- Dat doen ze (They do)

- Dat doen zij (They do)

- In the first one lets one see that it is something that people generally do, in the second is something specific that people we are referring to.

Verbs

Verbs are conjugated from a root. Simple tenses are formed by adding suffixes to the root and compound tenses by adding an auxiliary verb. The general way to find the stem of a verb is to remove the suffix -en from the infinitive. For example, for the verb werken (to work) the stem would be werk. In many cases it is necessary to adapt the orthography to maintain a closed or open vowel: horen (to hear) has the root hoor. In other cases, an affricate consonant is replaced by a fricative: verhuizenen (to mudar) has the root verhuis. These changes are not considered as irregularities. There are few apart.

The tenses and their conjugation in regular verbs are listed below, ignoring some orthographic singularities or when the order of the words is altered.

NON-PERSONAL FORMS

- Infinitive

root + in werken work

- Past participle

ge + root + t/d gewerkt worked

- There are two groups of verbs, depending on the end of the raw root:

- If the root ends in k, f, t, c, h, p, s, added -t.

- In the rest of cases, added - d.

- There are two groups of verbs, depending on the end of the raw root:

- The compound verbs to which a prefix is added to the root form the participle in a different way.

- If the prefix is separable: prefix + ge + root + t/d (samenwerken - samengewerkt)

- If the prefix is not separable: prefix + root + t/d (verhalen - verhalend)

- The compound verbs to which a prefix is added to the root form the participle in a different way.

- Participle present

root + in + d werkend worker It has no exact equivalent in Spanish, it works as adjective

- Continuous forms

- There is no form of gerundium in Dutch. One of the following constructions is used to indicate a development action:

- Verbo zijn + aan het + Infinitive in general cases:

- Ik ben aan het werken (I'm working)

- Verbo liggen/zitten/staan/lopen/hangen + you + Infinitive when you want to nuance the situation in which the subject develops the action:

- Hij staat te werken (He is working) (standing)

- Hij zit te werken (He's working) (sitting)

- There is no form of gerundium in Dutch. One of the following constructions is used to indicate a development action:

PERSONAL FORMS

- Present

1.a singular: root Ik werk I work. 2.a singular:

3.a singularroot + t Jij werkt

Hij werktYou work.

He works.Plural: root + in We werken

Jullie werken

Zij werkenWe work.

You guys work.

They work.

- Past

Singular: root + te/de Ik werkte

Jij werkte

Hij werkteI worked.

You worked.

He worked.Plural: root + ten/den We werkten

Jullie werkten

Zij werktenWe worked.

You guys worked.

They worked.

- Perfect choice

Assistant hebben/zijn (in present) + past partition Ik heb gewerkt

Jij hebt gewerkt

Hij heeft gewerkt

Wij hebben gewerkt

Jullie hebben gewerkt

Zij hebben gewerktI've worked.

You've worked.

He's worked.

We've worked.

You guys worked.

They've worked.

- When using the auxiliary hebben or zijn we find three groups of verbs:

- Most verbs use only the auxiliary hebben.

- Some verbs use only the auxiliary zijn.

- Some verbs can be used with hebben or zijn, but it is not possible to choose, it is the context or the sense of the phrase that determines which is the auxiliary to be used.

- As a general rule, when a state change is indicated or an address is used zijn and in the rest of the cases hebben.

- When using the auxiliary hebben or zijn we find three groups of verbs:

- Pretérito pluscuamperfecto

Assistant hebben/zijn (in the past) + past partition Ik had gewerkt

Jij had gewerkt

Hij had gewerkt

Wij Hadden gewerkt

Jullie Hadden gewerkt

Zij Hadden gewerktI had worked.

You had worked.

He had worked.

We had worked.

You had worked.

They had worked.

- Use of the auxiliary hebben or zijn follows the same rules as for the perfect preterite.

- Future

Assistant Zullen (in present) + Infinitive Ik zal werken

Jij zal werken

Hij zal werken

Wij Zullen werken

Jullie Zullen werken

Zij Zullen werkenI'll work.

You'll work.

He'll work.

We'll work.

You will work

They'll work.

- The use of the future is rare in Dutch, limiting itself in practice to the press, official writings or when it indicates a certain promise. Usually to talk about future actions is used:

- The present along with a temporary indication as "Morgen vertrek ik naar Amsterdam" (Mañana calving to Amsterdam).

- The verb gaan (ir) as in Spanish the verbal perifrasis "ir a": "Hij gaat meer studeren" (He will study more).

- The use of the future is rare in Dutch, limiting itself in practice to the press, official writings or when it indicates a certain promise. Usually to talk about future actions is used:

- Perfect future

Assistant hebben/zijn (in future) + past partition

♪ Zullen (in present) + hebben/zijn } + past partitionIk zal hebben gewerkt

Jij zal hebben gewerkt

Hij zal hebben gewerkt

Wij Zullen hebben gewerkt

Jullie Zullen hebben gewerkt

Zij Zullen hebben gewerktI'll have worked.

You've worked.

He'll have worked.

We'll have worked.

You'll have worked.

They'll have worked.

- Use of the auxiliary hebben or zijn follows the same rules as for the perfect preterite.

- Conditional

Assistant zouden (in the past) + Infinitive Ik zou werken

Jij zou werken

Hij zou werken

Wij zouden werken

Jullie zouden werken

Zij zouden werkenI would work.

You'd work.

He'd work.

We'd work.

You guys would work.

They would work.

- Perfect seasoning

Assistant hebben/zijn (on conditional) + past partition

♪ Zullen (in the past) + hebben/zijn } + past partitionIk zou hebben gewerkt

Jij zou hebben gewerkt

Hij zou hebben gewerkt

Wij zouden hebben gewerkt

Jullie zouden hebben gewerkt

Zij zouden hebben gewerktI would have worked.

You would have worked.

He would have worked.

We would have worked.

You would have worked.

They would have worked

- Use of the auxiliary hebben or zijn follows the same rules as for the perfect preterite.

Simple sentences

Dutch is generally considered to have an SOV structure (verbs at the end of sentences) with the particularity that a verb comes before the second position. This will be seen when talking about compound sentences, since in simple sentences having a single verb simplifies its structure.

In simple sentences the structure is similar to Spanish: SVO, however Dutch actually uses a CL-V2 structure, which means that what matters is that the conjugated form of the verb goes always > in the second position. This becomes evident when, to emphasize, some complement is placed before the sentence:

| Ik | ga | morgen | metro | naar Antwerpen | I'm on a bus tomorrow to Antwerp. |

| Morgen | ga | ik | metro | naar Antwerpen | I'm going by bus to Antwerp tomorrow. |

| Met bus | ga | ik | morgen | naar Antwerpen | By bus I go to Antwerp tomorrow |

| Naar Antwerpen | ga | ik | morgen | metro | I'm going to Antwerp tomorrow by bus |

In the above example you can see two basic rules of simple sentence construction in Dutch:

- that the verb (in red) is always the second element of prayer.

- that the subject (in blue) always goes next to the verb.

Therefore, the normal order is S+V, with the subject preceding the verb, but when a complement is emphasized and it is placed before the sentence, the order is altered V+S to maintain the verb in his position; this phenomenon is known as “inversion”.

Regarding the different complements that can be added to the sentence, the normal order (without emphasizing any of them) is first the complements of Time, then those of Mode and Frequency and lastly those of Place.

| Ik | ga | morgen | metro | naar Antwerpen | |

| S | V | Time | Mode | Place |

Compound sentences (with more than one verb)

If a sentence contains more than one verb, then it can be clearly seen that the grammatical structure of Dutch is an SOV in which a single verb (in the conjugated form) precedes second position, leaving the other verbs at the end of prayer.

Auxiliary verbs and modals

If it is about the use of auxiliary verbs, modal verbs or any other with a use similar to the verbal periphrases of Spanish, all the verb forms are placed at the end of the sentence, with the exception of the conjugated form, which is the only one that goes to the second position of the sentence:

- Composite times (with hebben or zijn): perfect preterito, pluscuamperfecto...

| Ik | heb | gisterenavond | of keuken | gepoetst | I cleaned the kitchen last night. | ||

| S | VC | Remaining verbs |

- Times that use an auxiliary verb: future, conditional...

| We | zouden | nu | een glacier water | drink | We'd drink a glass of water now | ||

| S | VC | Remaining verbs |

- Verbs or verbal signs: duty, want, go to...

| Jullie | moeten | het raam | elke morgen | openmaken | You must open the window every morning. | ||

| S | VC | Remaining verbs |

- Any combination of all the above:

| Jij | wilde | brood | gaan kopen | You wanted to go buy bread. | ||

| S | VC | Remaining verbs | ||||

| Ik | zou | Kazakh | hebben willen gaan kopen | I would have wanted to go buy cheese | ||

| S | VC | Remaining verbs |

- *This last sentence is shown as an example of how all verbs are placed at the end of the sentence, but it sounds so unnecessaryly complicated almost even more in Dutch than in Spanish.

Subordinate clauses

In subordinate clauses, all verbs, including conjugated forms, are always placed at the end of the sentence. It is as if the main clause has already used the possibility of bringing a verb forward to the second position, being no longer available for the subordinate clause that performs a certain function in the main one.

|

| I went yesterday to ask for the book. you're gonna talk about tomorrow.. | |||||||||||||

| See that the subordinate has all the verbs at the end: | |||||||||||||||

| you're gonna talk about tomorrow. |

Coordinate sentences

In coordinated or juxtaposed sentences there is no main clause, so they all behave as independent sentences with a verb in the second position and can also have other verbs at the end of each one.

As an example Three coordinated sentences are given in which each is seen to have an independent sentence structure. The first with a verbal periphrasis and several final verbs, the second with a modal verb and inversion by emphasizing daarna (after) and the third that includes a subordinate clause (indicated with italics).

| Ik | ga | mijn boek | uitlezen | in | daarna | kan | jij | het | lezen | Maar | het | is | jammer | dat | jouw broer | niet graag | leest | |||||

| S1 | VC1 | Remaining verbs | Nexo | VC2 | S2 | Remaining verbs | Nexo | S3 | VC3 | Nexo | S3b | VC3b |

| Approximate translation: | I'm gonna finish reading my book. | and | Then you can read it. | but | It's a shame. your brother doesn't like to read |

Exceptions

The exceptions to the rule of leaving verbs at the end of the sentence are:

- Long time, mode or place supplements (and only if they start with a preposition): One of the complements can be postponed at the end of the sentence, after the verbs:

- Normal order: Ik heb Jan in de nieuwe winkel op de Grote Markt gezien.

- Setting: Ik heb Jan gezien in de nieuwe winkel op de Grote Markt.

- The subordinate prayers: They remain behind the verb block that close the main sentence:

- Ik heb Jan gezien toen ik naar de dokter ging.

In any case, the subordinate clause also fulfills the function of complement (in this case, of time).

History

The history of the Dutch language begins around AD 450-500. after Old Frankish (Frankish), one of the many languages of the West Germanic tribes, was split by the Second Germanic consonant shift while at about the same time the expired "Ingaevonic" nasal law » led to the development of the direct ancestors of modern Dutch, Low Saxon, Frisian and English.

Northern Old Frankish dialects generally did not participate in either of these two changes, except for a small number of phonetic changes that are hitherto known as "Old Low Frankish"; "low" refers to dialects that were not influenced by the consonant shift. Within Old Low Frankish there are two subgroups: Old Low East Frankinc and Old Low West Frankinc, which is better known as Old Netherlandish. East Low Frankish would have eventually been absorbed by Netherlandish, as the latter became the dominant form of Low Franconian. Since the two groups were so similar, it is often very difficult to determine whether a text is "Old Netherlandish" or "Old Low East Frankish." Hence, many linguists often do not differentiate them.

Dutch, coincidentally like other Germanic languages, is conventionally divided into three phases. In the development of Dutch these phases were:

- 450/500 - 1150 - Old Dutch (First attested to the Sálica Act).

- 1150/1500 - Dutch average (Also called "Diet» in popular use, though not by linguists).

- 1500 - to the present - Modern Dutch (He saw the creation of the standard Dutchman and includes the contemporary Dutchman.)

The transition between those languages was very gradual, and one of the few moments where linguists can spot something of a revolution is when Standard Dutch emerged and quickly became self-consecrated. It can be noted that Standard Dutch is very similar to most Dutch dialects.

The development of the Dutch language is illustrated by the following sentence in Old, Middle and Modern Dutch.

- «Irlôsin sun frith sêla mîna fan thên thia ginâcont mi, wanda under managon he was mit mi.» (Old Dutch)

- «Erlossen sal [hi] in vrede siele mine van dien die genaken mi, want onder managon he was met mi.» (Dutch average)

(Using the same word order)

- «Verlossen zal hij in vrede ziel mijn van degenen die [te] na komen mij, want onder guard hij was met mij.» (Modern Dutch)

(Using correct contemporary Dutch syntax)

- «Hij zal mijn ziel in vrede verlossen van degenen die mij te na komen, want onder sailingn was hij met mij.» (Modern Dutch)

- "He will redeem my soul from the war against me in peace, for among many he was with me." (Translation to Spanish).

A process of standardization began in the "Middle Ages", especially under the influence of the Burgundian Ducal Court of Dijon (Brussels after 1477). The Flemish and Brabant dialects were the most influential at that time. The standardization process became stronger at the beginning of the 16th century, based mainly on the urban dialect of Antwerp. In 1585 Antwerp fell under the rule of the Spanish army and many fled to the northwest of the Netherlands, especially to the province of Holland, (today North Holland and South Holland), where the urban dialects of that province had an influence. In 1637 an important step was taken towards the unification of the language with the first important translation of the Bible into Dutch so that the inhabitants of the United Provinces could understand it.

Contenido relacionado

Mayan languages

Mirandés (Asturleone from Tierra de Miranda)

Absorption (linguistics)