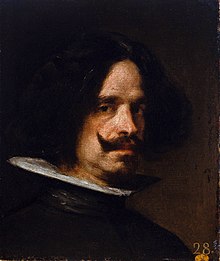

Diego Velazquez

Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez (Seville, baptized June 6, 1599-Madrid, August 6, 1660), known as Diego Velázquez, was a Spanish Baroque painter considered one of the greatest exponents of Spanish painting and a master of universal painting. He spent his early years in Seville, where he developed a naturalistic style of dark lighting, influenced by Caravaggio and his followers. At the age of 24 he moved to Madrid, where he was appointed painter to King Felipe IV and four years later he was promoted to chamber painter, the most important position among court painters. To this work he dedicated the rest of his life. His work consisted of painting portraits of the king and his family, as well as other paintings intended to decorate royal mansions. His presence at court allowed him to study the royal collection of paintings which, together with the teachings of his first trip to Italy, where he got to know both ancient painting and what was done in his time, were decisive influences in evolving into a style of great luminosity, with quick and loose brushstrokes. In his maturity, from 1631, he painted in this way great works such as The Surrender of Breda . In his last decade his style became more schematic and sketchy, reaching an extraordinary mastery of light. This period began with the Portrait of Pope Innocent X, painted on his second trip to Italy, and his last two masterpieces belong to it: Las Meninas and Las spinners.

His catalog consists of about 120 or 130 works. His recognition as a universal painter came late, around 1850. He reached his maximum fame between 1880 and 1920, coinciding with the time of the French impressionist painters, for whom he was a benchmark. Manet was amazed at his work and described him as a "painter's painter" and "the greatest painter that ever lived." The fundamental part of his paintings that made up the royal collection is preserved in the Museo del Prado in Madrid.

Biographical review

Early years in Seville

He was baptized on June 6, 1599 in the church of San Pedro in Seville. Regarding the date of his birth, Bardi ventures to say, without giving further details, that he was probably born the day before his baptism, that is, June 5, 1599.

His parents were Juan Rodríguez de Silva, born in Seville, although of Portuguese origin (his paternal grandparents, Diego Rodríguez and María Rodríguez de Silva, had settled in the city from Porto), and Jerónima Velázquez, Sevillian by birth They had married in the same church of San Pedro on December 28, 1597. Diego, the firstborn, would be the eldest of eight siblings. Velázquez, like his brother Juan, also an "image painter", adopted the last name of his mother according to the widespread custom in Andalusia, although towards the middle of his life he also sometimes signed "Silva Velázquez", using the second paternal surname.

It has been stated that the family was among the small nobility of the city. However, and despite Velázquez's noble claims, there is insufficient evidence to confirm this. The father, perhaps a nobleman, was an ecclesiastical notary, a profession that could only correspond to the lowest levels of the nobility and, according to Camón Aznar, he must have lived with great modesty, close to poverty. The maternal grandfather, Juan Velázquez Moreno, he was a hosier, a mechanical trade incompatible with the nobility, although he was able to allocate some savings to real estate investments. The painter's relatives claimed as proof of his nobility that, since 1609, the city of Seville had begun to return to his great-grandfather Andrés the tax that It weighed on "the white of meat", a consumption tax that only the pecheros had to pay, and in 1613 the same began to be done with the father and grandfather. Velázquez himself was exempted from paying him since he reached the age of majority. However, this exemption was not judged sufficient accreditation of nobility by the Council of Military Orders when in the fifties the file was opened to determine the supposed nobility of Velázquez, recognized only to the paternal grandfather, who was said to have been considered as such in Portugal and Galicia.

Learning

The Seville in which the painter was trained was the richest and most populous city in Spain, as well as the most cosmopolitan and open in the Empire. It had a monopoly on trade with America and had an important colony of Flemish and Italian merchants. It was also a very important ecclesiastical seat and had great painters.

His talent surfaced at a very early age. As recently as ten years old, according to Antonio Palomino, he began his training in the workshop of Francisco Herrera el Viejo, a prestigious painter in Seville in the 17th century , but of a very bad character and whom the young student would not have been able to stand. The stay in Herrera's workshop, which could not be documented, must necessarily have been very short, since in October 1611 Juan Rodríguez signed the "letter of apprenticeship" of his son Diego with Francisco Pacheco, committing himself to him for a period of time. six years, counting from December 1610, when the effective incorporation into the workshop of what would be his father-in-law could have taken place.

In the workshop of Pacheco, a painter linked to the ecclesiastical and intellectual environments of Seville, Velázquez acquired his first technical training and his aesthetic ideas. The apprenticeship contract established the usual conditions of servitude: the young apprentice, installed in the master's house, had to serve him "in the happiness of your house and in everything else that you tell him and order him to be honest and possible to do", mandates that used to include grinding the colors, heating the glues, decanting the varnishes, stretching the canvases, and assembling frames, among other obligations., and to teach him the "art well and fully according to how you know it without hiding anything from him".

San Buenaventura receives the habit of San Francisco.

Final Judgment.

Pacheco was a man of wide culture, author of an important treatise, The art of painting, which he never saw published in his lifetime. As a painter he was quite limited, a faithful follower of the models of Raphael and Michelangelo, interpreted in a hard and dry way. However, as a draftsman he produced excellent pencil portraits. Even so, he knew how to direct his disciple and not limit his abilities.Pacheco is better known for his writings and for being Velázquez's teacher than as a painter. In his important treatise, published posthumously in 1649 and essential for understanding Spanish artistic life at the time, he remains faithful to the idealist tradition of the previous century XVI and little prone to the progress of Flemish and Italian naturalist painting. However, he shows his admiration for the painting of his son-in-law and praises the still lifes with figures of a markedly naturalistic character that he painted in his early years. He had great prestige among the clergy and was very influential in Sevillian literary circles that brought together the local nobility.

This is how Pacheco described this period of apprenticeship: «My son-in-law, Diego Velásques de Silva, grew up with this doctrine [of drawing] when he was a boy. now crying, now laughing, without forgiving any difficulty. And he made for him many heads of charcoal and enhancement on blue paper, and of many other natural ones, with which he gained certainty in portraying.

No drawing of the ones he must have made of this apprentice has been preserved, but the repetition of the same faces and people in some of his works from this period is significant (see for example the boy on the left in Old Woman Frying Eggs or in El aguador de Sevilla).

Justi, the first great specialist on the painter, considered that in the brief time he spent with Herrera he must have transmitted the initial impulse that gave him greatness and singularity. He must have taught him “hand freedom”, which Velázquez would not achieve until years later in Madrid, although free execution was already a known feature in his time and had previously been found in El Greco. Possibly his first teacher served as an example in the search for his own style, since the analogies found between the two are only of a general nature. In Diego's early works one finds a strict drawing attentive to perceiving the exactitude of the model's reality, severely plastic, totally opposed to the loose contours of the tumultuous fantasy of Herrera's figures. He continued learning from him with a totally different teacher. Just as Herrera was a very temperamental born painter, Pacheco was educated but little painter, since what he valued most was orthodoxy. Justi concluded when comparing his paintings that Pacheco exerted little artistic influence on his disciple. He had to exert a greater influence on him in theoretical aspects, both of an iconographic nature, for example in his defense of the Crucifixion with four nails, as in what refers to the recognition of painting as a noble and liberal art, compared to the merely artisan character with which it was perceived by most of his contemporaries.

It must be noted, however, that if he had been a disciple of Herrera el Viejo, he would have been one at the beginning of his career, when he was around twenty years old and had not even examined himself as a painter, which he would only do in 1619 and precisely before Francisco Pacheco. Jonathan Brown, who does not take into account the supposed stage of training with Herrera, points to another possible early influence, that of Juan de Roelas, present in Seville during the years of Velázquez's apprenticeship. Having received important ecclesiastical commissions, Roelas introduced in Seville the incipient naturalism of Escorial, different from that practiced by the young Velázquez.

His beginnings as a painter

After the apprenticeship period, on March 14, 1617, he passed the exam before Juan de Uceda and Francisco Pacheco that allowed him to join the Seville painters' guild. He received a license to practice as a "master of imagery and oil", being able to practice his art throughout the kingdom, have a public store and hire apprentices. The scant documentation preserved from his Sevillian period, related almost exclusively to family matters and economic transactions, which indicate a certain family ease, only offer one piece of information related to his profession as a painter: the apprenticeship contract that Alonso Melgar, father of Diego Melgar, aged thirteen or fourteen, signed in the first days of February 1620 with Velázquez so that he taught him his trade.

Before turning 19, on April 23, 1618, he married Juana Pacheco, daughter of Francisco Pacheco, who was 15 years old in Seville, having been born on June 1, 1602. His two daughters were born in Seville: Francisca, baptized on May 18, 1619, and Ignacia, baptized on January 29, 1621. It was frequent among the painters of Seville of his time to unite by kinship ties, thus forming a network of interests that facilitated jobs and commissions.

His great quality as a painter was already manifested in his first works made when he was only 18 or 19 years old, still lifes with figures such as Lunch from the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, or the Old Frying Eggs from the National Gallery of Scotland in Edinburgh, subject and technique completely alien to what was done in Seville, also opposed to the models and theoretical precepts of his teacher, who nevertheless was going to do, as a result of them, a defense of the pictorial genre of the still life:

Shouldn't the cars be estimated? Of course, if they are painted as my son-in-law paints them up with this part without leaving room for others, and they deserve great estimation; for with these principles and portraits, that we will speak later, he found the true imitation of the natural encouraging the spirits of many with his powerful example.

In these early years he developed an extraordinary mastery, in which his interest in mastering the imitation of life is revealed, achieving the representation of relief and qualities, through a chiaroscuro technique that recalls the naturalism of Caravaggio, although it is unlikely that the young Velázquez could have become acquainted with any of the Italian painter's works. In his paintings a strong directed light accentuates the volumes and simple objects that appear prominent in the foreground. The genre painting or still life, of Flemish origin, of which Velázquez was able to learn the engravings of Jacob Matham, and the so-called pittura ridicola, practiced in northern Italy by artists such as Vincenzo Campi, with his representation of everyday objects and vulgar types, could have served him to develop these aspects as well as chiaroscuro lighting. Proof of the early reception in Spain of paintings of this genre is found in the work of a modest painter from Úbeda named Juan Esteban.

In addition, the first Velázquez was able to see works by El Greco, by his disciple Luis Tristán, a practitioner of a personal chiaroscuro style, and by a currently little-known portrait painter, Diego de Rómulo Cincinnato, whom Pacheco praised. The Santo Tomás from the Orleans Museum of Fine Arts and the San Pablo from the National Art Museum of Catalonia, would show knowledge of the first two. The Sevillian clientele, mostly ecclesiastical, demanded religious themes, devotional paintings and portraits, so the painter's production at this time also focused on religious commissions, such as the Immaculate Conception of the National Gallery in London and its partner, the San Juan en Patmos, from the convent of shoe-fitting Carmelites in Seville, with a marked sense of volume and a manifest taste for the textures of materials; the Adoration of the Magi from the Prado Museum or the Imposition of the chasuble on Saint Ildefonso from the Seville City Council. Velázquez, however, occasionally approached religious themes in the same way as his still lifes with figures, as in Christ in the House of Martha and Mary at the National Gallery in London or in The Supper at Emmaus from the National Gallery of Ireland, also known as La mulatta, of which a possibly autograph replica at the Art Institute of Chicago suppresses the religious motif, reduced to still life profane. This way of interpreting the natural allowed him to get to the bottom of the characters, early demonstrating a great capacity for portraiture, transmitting the inner strength and temperament of those portrayed. Thus, in the portrait of Sor Jerónima de la Fuente from 1620, of which two very intense specimens are known, where she conveys the energy of that nun who left Seville at the age of 70 to found a convent in the Philippines.

The Old Woman Frying Eggs from 1618 and El aguador de Sevilla made around 1620 are considered masterpieces of this period. In the first he demonstrates his mastery in the row of objects in the front row using strong, intense light that highlights surfaces and textures. The second, a painting that he took to Madrid and gave to Juan Fonseca, who helped him position himself at court, has excellent effects: the large clay jug captures the light in its horizontal grooves while small transparent drops of water slide across its surface.

His works, especially his still lifes, had a great influence on contemporary Sevillian painters, there being a large number of copies and imitations of them. Of the twenty works that survive from this period, nine can be considered still lifes.

Quick recognition in court

In 1621 Felipe III died in Madrid and the new monarch, Felipe IV, favored a nobleman from a Sevillian family, Gaspar de Guzmán, later Count-Duke of Olivares, who soon became the all-powerful favorite of the king. Olivares advocated that the court be made up mostly of Andalusians. Pacheco must have understood it as a great opportunity for his son-in-law, seeking the appropriate contacts so that Velázquez could be presented at court, where he was going to travel under the pretext of seeing the painting collections of El Escorial. His first trip to Madrid took place in the spring of 1622. Velázquez must have been introduced to Olivares by Juan de Fonseca or by Francisco de Rioja, but according to Pacheco, "it was not possible to portray the king although it was attempted", so that the painter returned to Seville before the end of the year. The one who did portray the one commissioned by Pacheco, who was preparing a Book of Portraits, was the poet Luis de Góngora, who was the king's chaplain.

Thanks to Fonseca, Velázquez was able to visit the royal painting collections, of enormous quality, where Carlos I and Felipe II had collected paintings by Titian, Veronese, Tintoretto and the Bassanos. According to Julián Gállego, then he must have understood the artistic limitation of Seville and that in addition to the imitation of nature there was "a poetry in the painting and a beauty in the intonation". The later study of the royal collection, especially the Titians, had a decisive influence on the stylistic evolution of the painter, who went from the austere naturalism of his Sevillian period and the severe earthy tones to the luminosity of silver grays and transparent blues in his maturity.

Shortly later, Pacheco's friends, mainly Juan de Fonseca, who was royal chaplain and had been a canon of Seville, managed to get the count-duke to call Velázquez to portray the king. Pacheco related it like this:

The one of 1623 was called [to Madrid] of the Mesmo don Juan (by order of Count Duque); he stayed in his house, where he was given and served, and made his portrait. He took him to the palace that night a son of the count of Peñaranda, a waiter of the Infante Cardinal, and in one hour all the palaces, the Infants and the King, who was the greatest qualification he had. It was ordained that he portrayed the infant, but it seemed more convenient to do that of his Majesty first, although he could not be so presto by great occupations; in fact it was done in 30 August, 1623, at the pleasure of His Majesty, and of the Infants and Count Duke, who claimed not to have portrayed the king until then; and the same felt all the lords who saw him. He also made a sketch of the Prince of Wales, who gave him a hundred shields.

None of these portraits have survived, although some have tried to identify a disputed Portrait of a Gentleman (Detroit Institute of Arts) with that of Juan de Fonseca. Nor is the name of the Prince of Wales, the future Carlos I, an excellent fan of painting and who had arrived in Madrid incognito to arrange his marriage with the Infanta María, sister of Felipe IV, an operation that did not prosper. The formal obligations of this visit must have been what delayed the first portrait of the king, which due to Pacheco's precise dating of August 30, must have been a sketch to be made in the workshop. It could have served as the basis for a first and also lost equestrian portrait, which in 1625 was exhibited on Calle Mayor, "with the admiration of the entire court and envy of those of l'arte", to which Pacheco declares himself a witness. Cassiano dal Pozzo, secretary of Cardinal Barberini, whom he accompanied on his visit to Madrid in 1626, reports that it was placed in the New Hall of the Alcázar forming a pair with the famous portrait of Charles V on horseback in Mühlberg by Titian, testifying to the "greatness" of the horse "è un bel paese" (a beautiful landscape), which according to Pacheco would have been painted from life, like everything else.

Everything indicates that the young monarch, six years younger than Velázquez, who had received drawing classes from Juan Bautista Maíno, immediately knew how to appreciate the artistic talents of the Sevillian. The consequence of that first meeting with the king was that in October 1623 Velázquez was ordered to transfer his place of residence to Madrid, being appointed king's painter with a salary of twenty ducats a month, occupying the vacancy of Rodrigo de Villandrando who had died. the previous year. That salary, which did not include the remuneration that could correspond to him for his paintings, was soon increased with other concessions, including an ecclesiastical benefice in the Canary Islands worth 300 ducats per year, granted at the request of the count-duke by Pope Urban VIII.

Velázquez's rapid rise provoked resentment from older painters, such as Vicente Carducho and Eugenio Cajés, who accused him of only being capable of painting heads. As Jusepe Martínez wrote, this led to a competition in 1627 between Velázquez and the other three royal painters: Carducho, Cajés and Angelo Nardi. The winner would be chosen to paint the main canvas of the Salón Grande of the Real Alcázar in Madrid. The subject of the painting was The expulsion of the Moors from Spain. The jury, chaired by Juan Bautista Maíno, among the sketches presented declared Velázquez the winner. The painting was hung in this building and was later lost in its fire (Christmas Eve 1734). This contest contributed to the change in taste of the court, abandoning the old style of painting and accepting the new painting.

In March 1627, he was sworn in as chamber usher, perhaps granted for his victory in this contest, with a salary of 350 ducats per year, and since 1628 he held the position of chamber painter, vacant on the death of Santiago Morán, considered the most important position among court painters. His main job was to make portraits of the royal family, so these represent a significant part of his production. Another job was to paint pictures to decorate the royal palaces, which gave him greater freedom in the choice of subjects and how to represent them, freedom that ordinary painters did not enjoy, tied to commissions and market demand. Velázquez could also accept private commissions, and it is recorded that in 1624 he received payment from doña Antonia de Ipeñarrieta for the portraits she painted of her deceased husband, the king and the count-duke, but since he moved to Madrid he only accepted commissions from influential members of the of the court. It is known that he painted several portraits of the king and the count-duke, some to be sent out of Spain, such as the two equestrian portraits that were sent to Mantua in May 1627 by the Gonzaga ambassador in Madrid, some of which were lost in the Alcázar fire of 1734.

Among the preserved works from this period, The Triumph of Bacchus, popularly known as The Drunkards, stands out especially, his first mythological composition, for which in July 1629 he received 100 ducats from the king's house. In it, classical antiquity is represented in a vigorous and daily way as a gathering of peasants of his time happily gathered to drink, where some Sevillian ways still persist. Among the portraits of the members of the royal family, The Infante Don Carlos (Museo del Prado) stands out, with a handsome appearance and somewhat indolent. Of the portraits not belonging to the royal family, the unfinished Portrait of a Young Man from the Alte Pinakothek in Munich can also be highlighted. The The Geographer from the Museum of Fine Arts of Rouen, inventoried in 1692 in the collection of the Marquis del Carpio as "a portrait of a philosopher's rod laughing with a balloon, original by Diego Velázquez". Also identified as Democritus and once attributed to Ribera, with whose style it bears a close resemblance, it causes some perplexity to critics due to the different way in which hands and head are treated, with very loose brushstrokes, and the tighter manner of the rest of the composition, which would be explained by a reworking of those parts around 1640.

His technique in this period values light more based on color and composition. In the portraits of the monarchs, as indicated by Palomino, it should reflect «the discretion and intelligence of the artist, to know how to choose, in the light or the most pleasing outline... that great art is necessary in sovereigns, to touch their defects, without endangering into flattery or stumbling into irreverence." They are the norms of the "court portrait" to which the painter is obliged to give the sitter the aspect that best responds to the dignity of his person and his condition. But Velázquez limits the number of traditional attributes of power (reduced to the table, the hat, the fleece or the hilt of the sword) to affect the treatment of the face and hands, more illuminated and progressively subjected to greater refinement. Very characteristic of his work, as in the Portrait of Felipe IV in Black (Museo del Prado), is the tendency to repaint, rectifying what has been done, which makes it difficult to accurately date his works. This constitutes what are called "regrets", attributable to the lack of previous studies and a slow way of working, given the phlegmatic nature of the painter, as defined by the king himself. After time, the old thing that was left below and what was painted on, emerges again in an easily perceptible way. In this portrait of the king it is verified in the legs and cloak, but X-rays reveal that the portrait was completely repainted, around 1628, introducing subtle variations on the underlying portrait, of which another possibly autograph copy exists in the Metropolitan Museum of Art from New York, a few years earlier. It is perceived in the same way in many later portraits, especially of monarchs.

In 1628 Rubens arrived in Madrid to carry out diplomatic efforts and stayed in the city for almost a year. It is known that he painted on the order of ten portraits of the royal family, most of them lost. When comparing the portraits of Felipe IV made by both painters, the differences are notable: Rubens painted the king allegorically, while Velázquez represented him as the essence of power. Picasso analyzed it like this: "Velázquez's Felipe IV is a different person from Rubens' Felipe IV". During this trip, Rubens also copied works from the king's painting collection, especially Titian. He had already copied his works on other occasions, since Titian represented for him one of his main sources of inspiration and encouragement. This work of copying was especially intense in the court of Felipe IV, who possessed the most important collection of works by the Venetian. The copies made by Rubens were acquired by Felipe IV and predictably also inspired Velázquez.

Rubens and Velázquez had already collaborated to some extent before this trip to Madrid, when Fleming used a portrait of Olivares painted by Velázquez to provide the drawing for an engraving made by Paulus Pontius and printed in Antwerp in 1626, in in which the allegorical frame was designed by Rubens and the head by Velázquez. The Sevillian must have seen him paint the real portraits and copies of Titian, and it was a great experience for him to observe the execution of those paintings by the two painters who would have the most influence on his own work. Pacheco affirmed, in effect, that Rubens in Madrid had had little contact with painters except his son-in-law, with whom he visited the collections of El Escorial, encouraging him, according to Palomino, to travel to Italy. For Harris there is no doubt that this This relationship inspired his first allegorical painting, The drunkards. that demonstrates a substantial change in your style at this time. For Calvo Serraller, what is almost certain is that Rubens promoted the first trip to Italy, since shortly after leaving the Spanish court in May 1629, Velázquez obtained permission to make his trip. According to Italian representatives in Spain, this trip it was to complete his studies.

First trip to Italy

Thus, after Rubens's departure and surely influenced by him, Velázquez requested permission from the king to travel to Italy to complete his studies. On July 22, 1629, he was granted two years' salary for the trip, 480 ducats, and also had another 400 ducats for the payment of various paintings. Velázquez traveled with a servant, and carried letters of recommendation to the authorities of the places he wanted to visit.

This trip to Italy represented a decisive change in his painting. Since the previous century, many artists from all over Europe traveled to Italy to see the center of European painting admired by all, a desire also shared by Velázquez. In addition, Velázquez was the painter of the King of Spain, and for this reason all doors were opened to him, allowing him to contemplate works that were only available to the most privileged.

He left the port of Barcelona on the ship belonging to Espínola, a Genoese general in the service of the Spanish king, who was returning to his land. On August 23, 1629, the ship arrived in Genoa, from where, barely stopping, she went to Venice, where the Spanish ambassador arranged for her to visit the main artistic collections in the different palaces. According to Palomino, he copied Tintoretto's works. As the political situation was delicate in the city, he stayed there for a short time and left for Ferrara, where he would meet Giorgione's painting; the effect that the work of this great innovator produced on him is unknown.

Later he was in Cento, interested in learning about the work of Guercino, who painted his paintings with very white lighting, treated his religious figures as ordinary characters and was a great landscape painter. For Julián Gállego, Guercino's work was the one that helped Velázquez the most to find his personal style.

In Rome, Cardinal Francesco Barberini, whom he had had the opportunity to portray in Madrid, gave him access to the Vatican rooms, where he spent many days copying the frescoes by Michelangelo and Raphael. He later moved to the Villa Medici, on the outskirts of Rome, where he copied his collection of classical sculpture. He didn't just study the old masters; At that time the great Baroque painters Pietro da Cortona, Andrea Sacchi, Nicolas Poussin, Claudio de Lorena and Gian Lorenzo Bernini were active in Rome. There is no direct testimony that Velázquez contacted them, but there are important indications that he knew first-hand what was new in the Roman artistic world.

The assimilation of Italian art in the style of Velázquez is verified in La forge of Vulcano and José's tunic, canvases painted at this time on his own initiative without commission in the middle. In La fragua de Vulcano , although elements of the Sevillian period persist, an important break with his previous painting is noted. Some of these changes can be seen in the spatial treatment: the transition to the background is smooth and the interval between figures is very measured. Also in the brushstrokes, previously applied in layers of opaque paint and now with a very light primer, so that the brushwork is fluid and the highlights produce amazing effects between the highlights and the shadows. Thus the contemporary painter Jusepe Martínez concluded: "he came much improved in terms of perspective and architecture."

In Rome he also painted two small landscapes in the garden of the Villa Médici: The entrance to the grotto and The Pavilion of Cleopatra-Ariadne, but there is no agreement between the historians about the time of his execution. Those who maintain that he was able to paint them during the first trip, particularly López-Rey, rely on the fact that the painter lived in Villa Médici in the summer of 1630, while most specialists have preferred to delay the date of their completion to the second trip, for considering his sketch technique to be very advanced, almost impressionistic. The technical studies carried out in the Museo del Prado, although in this case they are not conclusive, nevertheless support the execution around 1630. According to Pantorba, he proposed to capture two fleeting "impressions" in the way Monet would do two centuries after. The style of these paintings has often been compared to the Roman landscapes that Corot painted in the 19th century. landscapes lies not so much in their affairs as in their execution. Landscape studies taken from life were a rare practice, used only by a few Dutch artists established in Rome. Somewhat later, Claudio de Lorraine also made some well-known drawings in this way. But, unlike all of them, Velázquez was going to use oil directly, emulating the informal technique of drawing in his execution.

He remained in Rome until the autumn of 1630, and returned to Madrid via Naples, where he painted the portrait of the Queen of Hungary (Museo del Prado). There he was able to meet José de Ribera, who was in his pictorial plenitude.

Maturity in Madrid

At the end of his first trip to Italy, he was in possession of an extraordinary technique. At the age of 32 he began his period of maturity. In Italy he had completed his formative process studying the masterpieces of the Renaissance and his pictorial education was the broadest that a Spanish painter had received to date.

From the beginning of 1631, back in Madrid, he returned to his main task as royal portrait painter in a period of extensive production. According to Palomino, immediately after his return to court he presented himself to the count-duke, who He ordered him to go to thank the king for not having allowed himself to be portrayed by another painter in his absence. He was also expected to portray Prince Baltasar Carlos, born during his stay in Rome, whom he portrayed on at least six occasions.He established his workshop in the Alcázar and had assistants. At the same time, he continued his rise at court, not without litigation: in 1633 he received a wand of court bailiff, his majesty's cloakroom help in 1636, valet in 1643 and superintendent of works a year later. The documentation, relatively abundant for this stage, collected by Pita Andrade, presents, however, important gaps in relation to his artistic work.

In 1631, a young twenty-year-old assistant, Juan Bautista Martínez del Mazo, born in Cuenca, entered his workshop and nothing is known about his early training as a painter. Mazo married on August 21, 1633, Velázquez's eldest daughter, Francisca, who was 15 years old. In 1634 his mother-in-law gave him her position as chamber usher, to ensure Francisca's financial future. Mazo appeared closely linked to Velázquez from then on, as his most important assistant, but his own works would not go beyond being copies or adaptations of the Sevillian master, standing out, according to the Aragonese Jusepe Martínez, for his skill in painting small figures. His His skill in copying the works of his master, highlighted by Palomino, and his intervention in some works by Velázquez, which had remained unfinished at his death, has caused certain uncertainties, as there are still discussions among critics about the attribution of certain paintings. Velázquez or Mazo.

In 1632 he painted a Portrait of Prince Baltasar Carlos that is kept in the Wallace Collection in London, derived from an earlier portrait, Prince Baltasar Carlos with a dwarf, completed in 1631. For José Gudiol, this second portrait represents the beginning of a new stage in Velázquez's technique, which in a long evolution led him to his last paintings, wrongly called "impressionist". In some areas of this painting, especially the dress, Velázquez stops modeling the form, as it is, to paint according to the visual impression. In this way, he was looking for the simplification of pictorial work, but this required a deep knowledge of how light effects are produced in the things represented in the painting. He also requires great confidence, great technique and considerable instinct to be able to choose the dominant and main elements, those that would allow the viewer to accurately appreciate all the details as if they had really been painted in detail. He also requires a total mastery of chiaroscuro to give the sensation of volume. This technique was consolidated in the portrait Philip IV in chestnut and silver, where, through an irregular arrangement of light touches, the embroidery of the monarch's suit is suggested.

He participated in the two major decorative projects of the period: the new Palacio del Buen Retiro, promoted by Olivares, and the Torre de la Parada, a king's hunting lodge near Madrid.

For the Buen Retiro Palace, between 1634 and 1635 Velázquez made a series of five equestrian portraits of Felipe III, Felipe IV, their wives, and the crown prince. These decorated the front walls (ends) of the great Hall of Kingdoms, conceived with the purpose of exalting the Spanish monarchy and its sovereign. A wide series of canvases with battles showing the recent victories of the Spanish troops was also commissioned for its side walls. Velázquez made one of them, The Surrender of Breda, also called The Lances. Both the portrait of Philip IV on horseback and that of Prince are among the painter's masterpieces. Perhaps in the other three equestrian portraits he could have received help from his workshop, but in any case it is observed in the same highly skilled details that belong to Velázquez's hand. The arrangement of the equestrian portraits of King Felipe IV, the Queen and Prince Baltasar Carlos in the Hall of Realms, has been reconstructed by Brown based on descriptions of the time. The portrait of the prince, the future of the monarchy, was among those of his parents:

For the Torre de la Parada he painted three portraits of the king, his brother, the cardinal-infante Don Fernando, and the prince dressed as hunters. Also for that hunting lodge he painted three other pictures, Aesop , Menippus and Mars resting .

Around 1634, and also destined for the Buen Retiro Palace, Velázquez would have made a group of portraits of court jesters and «men of pleasure». The 1701 inventory mentions six full-length vertical paintings that could have been used to decorate a staircase or a room next to the queen's room. Only three of them are preserved in the Prado Museum: Pablo de Valladolid, The jester called Don Juan de Austria and The jester Cristóbal de Castañeda as Barbarossa. The disappeared Francisco de Ocáriz y Ochoa, who entered the king's service at the same time as Cristóbal de Pernía, and the so-called Juan Calabazas (Calabacillas con a pinwheel) from the Cleveland Museum of Art, whose authorship and date of execution are doubtful. Two other canvases of seated jesters decorated windows in the queen's room in the Parade Tower, described in inventories as two dwarfs, one of them «in a philosopher's outfit» and in an attitude of study, identified with Diego de Acedo, the Cousin, and the other, a jester seated with a deck of cards that can be recognized in Francisco Lezcano, the Child of Vallecas. The buffoon Calabacillas seated could have the same provenance. Two other portraits of buffoons were inventoried in 1666 by Juan Martínez del Mazo in the Alcázar: El Primo, who must have been lost in the fire of 1734, and The buffoon don Sebastián de Morra, painted around 1644. Much has been written about these series of jesters in which he compassionately portrayed their physical and mental deficiencies. Resolved in unlikely spaces, he was able to carry out stylistic experiments in them with absolute freedom.

Among his religious paintings from this period, the most noteworthy are San Antonio y San Pablo ermitaño, painted for his hermitage in the gardens of the Buen Retiro palace, and the Crucified Christ painted for the convent of San Plácido. According to Azcárate, in this Christ he reflected his religiosity expressed in an idealized and serene body with calm and beautiful forms.

The 1630s were for Velázquez the most active with brushes; almost a third of his catalog belongs to this period. Towards 1640 this intense production diminished drastically, and no longer recovered in the future. The reason for such a decline in activity is not known for sure, although it seems likely that he was caught up in courtly work in the service of the king, which helped him gain a better social position, but took time away from painting. As Superintendent of works, he also had to deal with conservation tasks and direct the reforms that were made in the Real Alcázar. Between 1642 and 1646 there was also accompanying the court in the "days of Aragón". There he painted a new portrait of the king "in the way he entered Lleida" to commemorate the lifting of the siege placed on the city by the French army, immediately sent to Madrid and exhibited in public at the request of the Catalans at court. the so-called Felipe IV in Fraga, after the city in Huesca where it was painted, in which Velázquez achieved a remarkable balance between the meticulousness of the head and the sparkling glitter of the clothing.

Velázquez held the position of valet in 1643, which was the highest recognition of royal favors, since he was one of the people closest to the monarch. After this appointment, a series of personal misfortunes followed, the death of his father-in-law and teacher Francisco Pacheco, on November 27, 1644, added to those that occurred at court: the rebellions of Catalonia and Portugal in 1640, fall from power of the one who had been his protector: the king's favorite, the Count-Duke of Olivares, together with the defeat of the Spanish tercios in the battle of Rocroi in 1643; the death of Queen Elizabeth in 1644; and finally the death, in 1646, of the crown prince Baltasar Carlos, at 17 years of age; These would also make these difficult years for Velázquez.

Second trip to Italy

Velázquez arrived in Málaga at the beginning of December 1648, from where he embarked with a small fleet on January 21, 1649 in the direction of Genoa, remaining in Italy until mid-1651, in order to acquire ancient paintings and sculptures for the king. He also had to hire Pietro da Cortona to fresco several ceilings in rooms that had been renovated in the Real Alcázar in Madrid. Not being able to buy antique sculptures, he had to settle for commissioning bronze copies by castings or molds obtained from famous originals. He, too, could not convince Pietro da Cortona to do the frescoes in the Alcázar, and instead hired Angelo Michele Colonna and Agostino Mitelli, experts in trompe l'oeil painting. This management work, more than the creative one itself, absorbed a lot of his time; he traveled searching for old master paintings, selecting ancient sculptures to copy and obtaining permission to do so. Again he toured the main Italian states in two stages: the first took him to Venice, where he purchased works by Veronese and Tintoretto for the Spanish monarch; the second, after settling in Rome, to Naples, where he met Ribera again and provided funds before returning to the Eternal City.

In Rome, at the beginning of 1650, he was elected a member of the two main organizations of artists: the Academy of Saint Luke in January, and the Congregazione dei Virtuosi del Pantheon on February 13. Membership in the Congregation of the Virtuosos gave him the right to exhibit on the portico of the Pantheon on March 19, Saint Joseph's Day, where he exhibited his portrait of Juan Pareja (Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York).

The portrait of Pareja was painted before the one made for Pope Innocent X. Victor Stoichita believes that Palomino related this in the way that best suited him, altering the chronology and accentuating the myth:

When he determined to portray himself to the Supreme Pontiff, he wanted to prevent himself before with the exercise of painting a head of the natural; he made that of Juan Pareja, his slave and sharp painter, so similar, and with so much vivacity, that having sent him with the same Couple to the censorship of some friends, they stood looking at the painted portrait, and to the original, with admiration and astonishment, without knowing who they were to speak, or who was to answer (...) that being style that the day of Saint Joseph is adorned the cloister of the Rotunda [the Pantheon of Agrippa] (where Raphael of Urbino is buried) with ancient and modern insign paintings, this portrait was put with so universal applause on that site, that by the vote of all the painters of different nations, everything else seemed painting, but this only truth; in whose attention was received Velázquez by

Stoichita highlights the legend forged over the years around this portrait and on the basis of this text on various levels: the contrast between the portrait-essay of the slave and the final portrait with the greatness of the pope; the images exhibited in an almost sacred space (in the tomb of Raphael, prince of painters); the universal applause of all the painters of different nations when contemplating him among distinguished ancient and modern paintings. In fact, it is known that a few months passed between one portrait and another, since Velázquez did not portray the pope until August of that year and, therefore, On the other hand, his admission as an academic had taken place before his exhibition.

As for Juan de Pareja, a slave and assistant to Velázquez, it is known that he was a Moorish, "of a mixed race generation and of a strange color" according to Palomino. It is unknown at what point he came into contact with the master, but in 1642 he signed already as a witness in a power of attorney granted by Velázquez. He was a witness again in 1647 and was again in 1653, signing on this occasion the power of attorney for Francisca Velázquez, the painter's daughter. According to Palomino, Pareja helped Velázquez with tasks mechanics, such as grinding the colors and preparing the canvases, without the master, because of the dignity of art, ever allowing him to occupy himself with painting or drawing. However, Pareja learned to paint secretly from his owner. In 1649 he accompanied Velázquez on his second trip to Italy, where he portrayed him and, according to what is known from a published document, on November 23, 1650, still in Rome, he granted him the letter of freedom, with the obligation to continue serving the painter. four more years.

The most important portrait he painted in Rome was that of Pope Innocent X. Gombrich considers that Velázquez must have felt the great challenge of having to paint the pope, and would be aware when contemplating the portraits that Titian and Raphael made of previous popes, considered masterpieces, who would be remembered and compared to these masters. Velázquez, likewise, made a great portrait, confidently interpreting the pope's expression and the quality of his clothing.

The excellent work on the pope's portrait triggered other members of the papal curia to want portraits of him by Velázquez. Palomino says that he made seven of the characters he cites, two unidentified and others that remained unfinished, a rather surprising volume of activity for Velázquez, considering a painter who lavished very little.

Many critics ascribe the Venus in the Mirror to this stage in Italy. Velázquez must have made at least two other female nudes, probably two more Venuses, one of them mentioned in the inventory of the goods he left behind at his death. Titian and Rubens had an influence on Velázquez painting, but due to its erotic implications it created serious reluctance in Spain. It should be remembered that Pacheco advised painters who were forced to paint a female nude to use honest women as models for the head and hands, imitating the rest of statues or engravings. Velázquez's Venus brings a new variant to the genre: the goddess she is lying on her back and shows her face to the viewer reflected in the mirror.

Jenifer Montagu discovered a notarial document proving the existence in 1652 of a Roman son of Velázquez, Antonio de Silva, a natural son and whose mother is unknown. Scholars have speculated about it and Camón Aznar pointed out that she could have been the model who posed for the nude of the Venus in the mirror, who perhaps was what Palomino called Flaminia Triunfi, an "excellent painter", to whom that Velázquez would have portrayed. Of this supposed painter, however, there is no other news, although Marini suggests that perhaps she can be identified with Flaminia Triva, twenty years old, sister and collaborator of Antonio Domenico Triva, a disciple of Guercino.

The surviving correspondence shows Velázquez's continuous delays to delay the end of the trip. Felipe IV was impatient and wanted his return. In February 1650 he wrote to his ambassador in Rome to urge him to return: «well, you know his phlegm, and let it be by sea, and not by land, because it could slow down and even more with natural of the". Velázquez was still in Rome at the end of November. The Count of Oñate reported his departure on December 2 and in the middle of the month he reported his passage through Modena. However, it was not until May 1651 that he embarked at Genoa.

Last decade: his pictorial peak

In June 1651 he returned to Madrid with numerous works of art. Shortly after, Felipe IV named him Royal Lodger, which elevated him to court and added a strong income to what he already received as a painter, valet, superintendent and as a pension. In addition, he received the amounts stipulated for the paintings he made. His administrative positions absorbed him more and more, including that of Royal Lodge, which took up a large amount of time to develop his pictorial work. Even so, some of his works correspond to this period. his best portraits and his masterpieces Las meninas and Las hilanderas.

The arrival of the new queen, Mariana of Austria, motivated the realization of several portraits. The marriageable infanta María Teresa was also photographed on several occasions, as she had to send her image to the possible husbands at the European courts. The new infantes, born to Mariana, also produced several portraits, especially Margarita, born in 1651.

At the end of his life he painted his two largest and most complex compositions, his works La fábula de Arachné (1658), popularly known as Las hilanderas, and the The most celebrated and famous of all his paintings, The Family of Felipe IV or Las Meninas (1656). In them we see the style of the last of him, where he seems to represent the scene through a fleeting vision. He used bold brushstrokes that seem disjointed up close, but seen from a distance take on their full meaning, anticipating the painting of Manet and the Impressionists of the 19th century , in which his style influenced so much. The interpretations of these two works have given rise to many studies and are considered two masterpieces of European painting.

The last two official portraits he painted of the king are very different from the previous ones. Both the bust in the Prado Museum and the debated one in the National Gallery are two intimate portraits where he appears dressed in black and only in the second with the Golden Fleece. According to Harris, they reflect the physical and moral decline of the monarch, of which he became aware. It had been nine years since he had portrayed him, and this is how Felipe IV himself showed his reluctance to let himself be painted: "I am not inclined to go through the phlegm of Velázquez, as if I did not see myself growing old."

The last commission he received from King Philip IV was the realization in 1659 of four mythological scenes for the Hall of Mirrors of the Real Alcázar in Madrid, where they were placed together with works by Titian, Tintoretto, Veronés and Rubens, the painters Monarch's favourites. Of the four paintings (Apollo and Marsyas, Adonis and Venus, Psyche and Cupid, and Mercury and Argos) Only the last one is preserved today, located in the Prado Museum, the other three being destroyed in the fire of the Real Alcázar on Christmas Eve of 1734, already in the time of Felipe V. During that fire, more than five hundred works by masters were lost. of painting and the building was reduced to rubble, until four years later the Royal Palace of Madrid began to be built on its site. The quality of the preserved canvas, and how rare among Spanish painters of the time were The themes dealt with in these scenes, which by their nature would include nudes, make the loss of these three paintings particularly serious.

According to the mentality of his time, Velázquez wanted to achieve nobility, and tried to enter the Order of Santiago, counting on the royal favor, which on June 12, 1658, granted him the habit of a knight. To be admitted, however, the suitor had to prove that his direct ancestors had also belonged to the nobility, not counting Jews or converts among them. For this reason, the Council of Military Orders opened an investigation into his lineage in July, taking statements from 148 witnesses. Significantly, many of them affirmed that Velázquez did not live from painting, but from his work at court, some of his closest friends, painters too, even saying that he had never sold a painting. At the beginning of April 1659, the Council concluded the collection of reports, rejecting the painter's claim as the nobility of his paternal grandmother or his maternal grandparents was not proven. In these circumstances, only the dispensation of the Pope could achieve that Velázquez was admitted to the Order. At the request of the king, Pope Alexander VII issued an apostolic brief on July 9, 1659, ratified on October 1, granting him the requested dispensation, and the king granted him nobility on November 28, thus overcoming the resistance of the Council of Órdenes, who on the same date dispatched the long-awaited title in favor of Velázquez.

In 1660 the king and court accompanied the Infanta María Teresa to Fuenterrabía, near the French border, where she met her new husband Louis XIV. Velázquez, as royal lodger, was in charge of preparing the accommodation for the entourage and decorating the pavilion where the meeting took place. The work must have been exhausting and on his return he fell ill with smallpox.

He fell ill at the end of July and, a few days later, on August 6, 1660, he died at three in the afternoon in Madrid. The following day, August 7, he was buried in the now-defunct church of San Juan Bautista, with the honors due to his position and as a knight of the Order of Santiago. Eight days later, on August 14, his wife, Juana, also died.

Contemporary documentation on the painter

His early biographers provided a wealth of basic information about his life and work. The first was Francisco Pacheco (1564-1644), a person very close to him as she was his teacher in his youth and also his father-in-law. In a treatise dedicated to the Art of Painting, completed in 1638, he gave ample information up to that date. He provided personal details about his apprenticeship, his early years at court, and his first trip to Italy. The Aragonese Jusepe Martínez, who treated him in Madrid and Zaragoza, included a brief biographical review in his Practical Discourses on the Most Noble Art of Painting (1673), with information on the second trip to Italy and the honors received at court. There is also a complete biography of the painter by Antonio Palomino (1655-1721), published in 1724, 64 years after Velázquez's death. This relatively late work, however, was based on the biographical notes taken by a friend of the painter, Lázaro Díaz del Valle, which have been preserved in handwriting, and the losses of one of his last disciples, Juan de Alfaro (1643- 1680). In addition, Palomino was a court painter, he was well acquainted with Velázquez's works from the royal collections and spoke with people who knew the painter as young men. He gave abundant information about his second trip to Italy, about his activity as a chamber painter and as a Palace official.

Various poetic eulogies, including some very early ones such as the sonnet dedicated by Juan Vélez de Guevara to an equestrian portrait of the king, Salcedo Coronel's panegyric to another of the count-duke, or Gabriel Bocángel's epigram to the Portrait of a lady of superior beauty, as well as news about specific works allow us to verify the rapid recognition of the painter in circles close to the court. Other news can be found in contemporary writers such as Diego Saavedra Fajardo or Baltasar Gracián, in the that his fame, although directly linked to his status as the king's portrait painter, transcends the merely courtly sphere. Very significant in this order are the comments of Father Francisco de los Santos, with news regarding his participation in the decoration of the Monastery of El Escorial.There are also many administrative documents on events that happened to him. However, nothing is known about his letters, personal writings, friendships or private life, which would allow us to investigate his life, his work and his thoughts. Which makes it difficult to understand the artist's personality.

Your interests in books are known. His library, very large for the time, consisted of 154 copies on mathematics, geometry, geography, mechanics, anatomy, architecture and art theory. Recently, several scholars through these books have tried to get closer to understanding his personality.

The artist

Evolution of his pictorial style

In his Sevillian beginnings, his style was that of tenebrist naturalism, using an intense and directed light; his heavily impastoed brushwork modeled the forms with precision, and his dominant colors were tan tones and coppery flesh.

For Xavier de Salas when Velázquez settled in Madrid, studying the great Venetian painters in the royal collection, he modified his palette and began to paint with grays and blacks instead of earthy colors. Still until the end of During his first period in Madrid, specifically until he made Los borrachos, he continued painting his characters with precise contours and highlighting them from the backgrounds with opaque brushstrokes.

On his first trip to Italy he undertook a radical transformation of his style. On this trip the painter tried new techniques, looking for light. Velázquez, who had been developing his technique in previous years, completed this transformation in the mid-1630s, where he is considered to have found his own pictorial language through a combination of loose brushstrokes of transparent colors and precise touches of pigment to highlight details.

From The Forge of Vulcano, painted in Italy, the preparation of the paintings changed and remained so for the rest of his life. It basically consisted of white lead applied with a spatula, which formed a very luminous background, complemented by increasingly transparent brushstrokes. In The Surrender of Breda and in the Equestrian Portrait of Baltasar Carlos, painted in the 1630s, completed this change. The use of light backgrounds and transparent layers of color to create great luminosity were frequent in Flemish and Italian painters, but Velázquez developed this technique to extremes never seen before.

This evolution occurred due to the knowledge of the work of other artists, especially the royal collection and the paintings he studied in Italy. Also because of his direct relationship with other painters, such as Rubens during his visit to Madrid and those he met on his first trip to Italy. Velázquez, therefore, did not do like the other painters who worked in Spain, who painted by superimposing layers of color. He developed his own style of diluted brushwork and quick, precise touches on detail. These small details were very important in the composition. The evolution of his painting continued towards greater simplification and speed of execution. His technique, with the passage of time, became more precise and schematic. It was the result of an extensive internal maturation process.

The painter did not have a fully defined composition when he started working; he rather preferred to adjust it as he progressed in the painting, introducing modifications that would improve the result. He rarely did preparatory drawings, he simply sketched the general lines of the composition. In many of his works, his famous corrections can be seen with the naked eye. The outlines of the figures are superimposed on the painting as they change their position, add or remove elements. Many of these adjustments can be seen with the naked eye: modifications in the position of the hands, in the sleeves, in the necks, in the dresses... Another custom of his was to touch up his works after they were finished; in some cases these touch-ups occurred much later.

The color palette he used was very small, using the same pigments throughout his life. What varied over time is the way of mixing and applying them.

The degree of finish is another fundamental part of your art and depends on the subject. The figures—particularly heads and hands—are always the most elaborate part; in the case of the portraits of the royal family, they are much more elaborate than in the buffoons, where the greatest technical liberties were taken. part of the painting Throughout his life, in many portraits and other mythological, religious or historical compositions, these outlined areas appear. For López-Rey it is clear that these sketched parts have an intrinsic expressive intensity, being well integrated into the composition of the painting, and can be considered part of Velázquez's art.

His drawings

Very few drawings of Velázquez are known, which makes it difficult to study them. Despite the news provided by Pacheco and Palomino, the first biographers of him, who speak of his work as a draftsman, his painting technique alla prima seems to exclude the execution of numerous previous studies. Pacheco refers to the drawings made during his apprenticeship by a boy who served as his model and tells that during his first trip to Italy he was staying in the Vatican, where he was able to draw frescoes by Raphael and Michelangelo freely. He was able to use those drawings many years later in The Fable of Arachne, when he used for the two main spinners the design of the ephebes located on the Persian Sibyl in the vault of the Sistine Chapel. Palomino, For his part, he recounts that he carried out drawing studies of the works of the Venetian painters of the Renaissance, "and particularly of the painting by Tintoretto, of the Crucifixion of Christ Our Lord, copious of figures". None of these works has been preserved.

According to Gudiol, the only drawing that is fully guaranteed to be by his hand is the study carried out for the portrait of Cardinal Borja. Drawn in pencil, when Velázquez was 45 years old, Gudiol says of it that "it is executed with simplicity but giving the precise value to lines, shadows, surfaces and volumes within the realistic tendency".

For the rest of the drawings attributed or related to Velázquez, there is no unanimity of criteria among historians, due to the diversity of techniques used. Gudiol only accepts with full conviction, in addition to the aforementioned portrait of Cardinal Borja, a girl's head and a female bust, in which the same girl appears portrayed, both executed with black pencil on linen paper and undoubtedly by the same hand. Both drawings are preserved in the National Library of Madrid and probably belong to his Sevillian period. Two very light pencil sketches, studies for figures of The Surrender of Breda, also preserved in the National Library of Madrid, are accepted as autographs by López-Rey and Jonathan Brown. Lately Mckim-Smith considers eight drawings of the pope sketched on two sheets of paper preserved in Toronto as authentic, as preparatory studies for the portrait of Innocent X.

This scarcity of drawings confirms the supposition that Velázquez began his paintings without previous studies by marking the initial lines of the composition on the canvas. This is corroborated in some sectors that he left unfinished in various paintings, where vigorous strokes appear, such as the left hand of the portrait of a man in the Pinacoteca de Múnich or the head of Felipe IV in the portrait of Montañés. This has been verified in other paintings by the painter kept in the Museo del Prado where by means of infrared reflectography, sometimes, the strokes of these essential lines of the composition are visible.

Acknowledgment of your painting

Velázquez's recognition as a great master of Western painting came relatively late. Until the beginning of the XIX century, his name rarely appeared outside of Spain among the artists considered major. part of his career was dedicated to the service of Felipe IV, so almost all his production remained in the royal palaces, places not very accessible to the public. Unlike Murillo or Zurbarán, he did not depend on ecclesiastical clientele and did few works for churches and other religious buildings, so he was not a popular artist.

In addition, he shared the general misunderstanding of some late Renaissance and Baroque painters such as El Greco, Caravaggio or Rembrandt, who had to wait three centuries to be understood by critics, who on the other hand exalted other painters such as Rubens and Van Dyck and in general those who persisted in the old style. Velázquez's poor fortune with criticism must have started early; In addition to the criticism from the court painters, who censured him knowing how to paint only "a head", Palomino recounts that the first equestrian portrait of Felipe IV submitted to public censorship was highly criticized, arguing that the horse was against the rules of art. and the angry painter erased a large part of the painting. In another place he spoke, however, of the excellent reception given by the public to that same portrait, collecting the laudatory verses of Juan Vélez de Guevara. Pacheco, in his time, He already warned of the need to defend this painting from the accusation of being mere blots. If even today any fan admires himself when contemplating up close a tangle of colors that at a distance takes on all its meaning, at that time, optical effects were still more disconcerting and impressive, and Velázquez when he adopted them shortly after his first trip to Italy, he was a constant source of discussion as a supporter of the new style.

The first knowledge of the painter in Europe is due to Antonio Palomino, a devoted admirer, whose biography of Velázquez, published in 1724 in volume III of The Pictorial Museum and Optical Scale, was translated abbreviated into Spanish. English in London in 1739, French in Paris in 1749 and 1762, and German in Dresden in 1781, serving from then on as a source and knowledge for historians. Norberto Caimo, in the Lettere d'un vago italiano ad un suo amico (1764), used Palomino's text to extol the "Principe de'Pittori Spagnuoli", who would have known masterfully unite Venetian coloring to Roman drawing. The first French trial of Velázquez dates back to before and can be found in volume V (1688) of the Entretiens sur les vies et sur les ouvrages des plus excellents peintres anciens et modernes by André Félibien. Limited his knowledge of Spanish painting to that preserved in the French royal collections, Félibien could only cite a landscape by Cleantes (by Collantes), and «plusieurs Portraits de la Maison d'Autriche», preserved in the basement of the Louvre and attributed to Velázquez. Responding to his interlocutor, who had asked him what he found admirable in the work of these two strangers, and placing them among painters of second rank, Félibien praised them "for having chosen and looked at nature in a very particular way", without the beautiful air of Italian painters. Velázquez's paintings of "inconceivable daring that, from a distance, have a surprising effect and even produce a total illusion".

Also in the 18th century the painter Anton Raphael Mengs considered that even lacking notions of ideal beauty due to his tendency to naturalism, he had managed to circulate the air around the painted things, and for this reason he deserves respect. In his letters to Antonio Ponz he praised some specific paintings for their wise imitation of life, particularly the Spinners, of his latest style, "which seems to have had no hand in the execution". The news transmitted by English travelers such as Richard Twiss (1775), Henry Swinburne (1775), Henry Swinburne (1775) also contributed to a better knowledge and appreciation of his painting. 1779) or Joseph Townsend (1786), who with the usual praise for the imitation of life, in which the Spanish are not inferior to the main masters of Italy or Flanders, valued the treatment of light and aerial perspective, in what Velázquez «leaves to all other painters pray enough behind him".

With the Enlightenment and its educational ideals, Goya, who on some occasion declared that he had no other teachers than Velázquez, Rembrandt and Nature, was commissioned to make engravings of some of Velázquez's works preserved in the royal collections. Diderot and D'Alembert, in the article «peinture» of L'Encyclopédie of 1791, described the life of Velázquez and some of his masterpieces: The Waterboy, The drunkards and The spinners. Shortly after, Ceán Bermúdez renewed his assessment of Palomino in his Diccionario (1800), expanding it with some works from his Sevillian stage. Many of these had already left Spain, according to what the painter Francisco Preciado de la Vega recounted to Giambatista Ponfredi in a letter dated 1765, alluding to the "bambochadas" that he had painted there, "in a rather colorful manner, and finished, according to the taste by Caravaggio" and that had been brought by foreigners. Velázquez's work began to be better known outside of Spain when foreign travelers visiting the country were able to see it at the Museo del Prado, which began showing the royal collections in 1819 Before, only those who had a special permit could see his work in the royal palaces.

Stirling-Maxwell's Study of the Painter, published in London in 1855 and translated into French in 1865, helped rediscover the artist; it was the first modern study on the life and work of the painter. The review of Velázquez's importance as a painter coincided with a change in artistic sensibility.

The definitive revaluation of the master was carried out by the impressionist painters, who perfectly understood his teachings, especially Manet and Renoir, who traveled to the Prado to discover and understand him. When Manet made his famous study trip to Madrid in 1865, the The painter's fame was already established, but no one was so amazed and he was the one who did the most for the understanding and appreciation of his art. He described him as the "painter's painter" and "the greatest painter that ever lived". The influence of Velázquez can be found, for example, in The Fife, where Manet is openly inspired by the painters of dwarfs and buffoons made by the Sevillian painter. We must also take into account the confusion about his work since At that time there was considerable chaos and a great lack of knowledge about his autograph works, copies, replicas of the workshop or erroneous attributions and their difference was not clear. Thus, in the period from 1821 to 1850, some 147 works attributed to Velázquez were sold in Paris, of which only one, The Lady with the Fan today preserved in London, is currently recognized as authentic by specialists.

Velázquez's emergence as a universal painter therefore occurred around 1850. In the second part of the century he was considered the supreme realist and the father of modern art. At the end of the century the interpretation of Velázquez as a proto-impressionist painter. Stevenson, in 1899, studied his paintings with a painter's eye, and found numerous connections between Velázquez's technique and the French Impressionists. José Ortega y Gasset placed Velázquez's moment of greatest fame between 1880 and 1920, coinciding with the time of his the French Impressionists.

Then the reverse happened, around 1920 impressionism and its aesthetic ideas declined, and with them the consideration of Velázquez. According to Ortega, a period of Velázquez's invisibility began.

Influences and tributes in 20th century art

The essential chapter that Velázquez constitutes in the history of art is perceptible today by the way painters of the XX century have judged his work. It was Pablo Picasso who paid his compatriot his most visible homage, with the series of canvases he dedicated to Las meninas (1957) reinterpreted in cubist style, but precisely preserving the original position Of the characters. Another famous series is the one dedicated by Francis Bacon in 1953 to the Study according to the portrait of Pope Innocent X by Velázquez. Salvador Dalí, among other expressions of admiration for the painter, produced a work in 1958 entitled Velázquez painting the Infanta Margarita with the lights and shadows of her own glory, followed in the year of the third centenary of his death of a Portrait of Juan de Pareja repairing a string on his mandolin and of his own version of Las meninas (1960), also evoked in The Apotheosis of the Dollar (1965), in which Dalí vindicated himself.

Velázquez's influence has also reached the cinema. It is particularly notable in the case of Jean-Luc Godard, who in Pierrot le fou (1965) staged a girl reading a text by Élie Faure dedicated to Velázquez, taken from his L& #39;Histoire de l'Art:

Vélasquez, après cinquante ans, ne peignait plus jamais une chose définie. Il errait autour des objets avec l'air et le crépuscule. Il surprenait dans l'ombre et la transparence des fonds les palpitations colorées dont il faisait le centre invisible de sa symphonie silencieuse.

Catalogue and museography

The preserved works of the painter are estimated to be between one hundred twenty and one hundred twenty-five canvases, a reduced number given the forty years of pictorial dedication. If we add the works to which there are references but which have been lost, he must have painted around one hundred and sixty paintings. In the first twenty years of activity, he painted over one hundred and twenty, at a rate of six per year, while in his last twenty years he only painted about forty paintings, at a rate of two per year. Palomino explained that this reduction occurred because the multiple activities the court took up a lot of his time.

The first catalog of Velázquez's work was produced by William Stirling-Maxwell in 1848 and included 226 paintings. The successive catalogs of other authors have gradually reduced the number of authentic works until reaching the current figure of 120-125. Of the current catalogues, the most widely used is that of José López-Rey, published in 1963 and revised in 1979. The first included one hundred and twenty works and the revision included one hundred and twenty-three.

The Prado Museum has some fifty works by the painter, the fundamental part of the royal collection, while other places and museums in Madrid have another ten works.

In the Museum of Art History in Vienna (Kunsthistorisches Museum) you can admire ten paintings, including five portraits from the last decade. These paintings, mostly portraits of the Infanta Margarita, were sent to the imperial court in Vienna so that her cousin Emperor Leopold, who had been betrothed to her at her birth, could observe her growth.

In the British Isles some twenty paintings are preserved and already in Velázquez's lifetime there were fans who collected his paintings. It is where there are more works from the Sevillian period and the only surviving Venus by Velázquez is preserved. The still lifes are in public galleries in London, Edinburgh and Dublin. Most of these works left Spain during the Napoleonic invasion.

There are another twenty works in the United States, half of which are in museums in New York.

Work

Included below is some of his best work to give an overview of his mature pictorial style, for which he is world renowned. First The Surrender of Breda of 1635 where he experimented with lightness. Then one of the best portraits of whom he was a specialist in the genre, that of Pope Innocent X painted in 1650. Lastly, his two late magisterial works Las meninas of 1656 and Las hilanderas of 1658.

The Surrender of Breda

This painting of the Battle of Breda was intended to decorate the great Hall of Kingdoms of the Buen Retiro Palace, together with other paintings of battles by various painters. The Salón de Reinos was conceived in order to exalt the Spanish monarchy and Felipe IV.

This is a work of total technical maturity, where he found a new way of capturing light. The Sevillian style has disappeared, the "caravaggista" way of treating the illuminated volume is no longer used. The technique becomes very fluid to the point that in some areas the pigment does not cover the canvas, revealing its preparation.In this painting, Velázquez finished developing his pictorial style. From then on, he will always paint with this technique, later making only small adjustments to it.

In the scene depicted, the Spanish general Ambrosio Espínola receives the keys to the conquered city from the Dutchman Justino de Nassau. The terms of the surrender were exceptionally mild and the defeated were allowed to leave the city with their arms. The scene is an invention, as the act of handing over the keys did not really exist.

As he went along, Velázquez modified the composition several times. He erased what he didn't like with light color overlays. Radiographs make it possible to distinguish the overlap of many modifications. One of the most significant is the one he made on the spears of the Spanish soldiers, a capital element of the composition, which were added at a later stage. The composition is articulated in depth through an aerial perspective. Between the Dutch soldiers on the left and the Spanish on the right there are faces strongly illuminated and others are treated in different levels of shadows. The figure of the defeated general treated with nobility is a way of highlighting the victor. To the right, Espínola's horse moves impatiently. The soldiers, some attend and others seem distracted. It is these small movements and gestures that take the rigidity out of the surrender and give it an appearance of naturalness.

Portrait of Pope Innocent X

The most acclaimed portrait during the painter's lifetime, and one that continues to arouse admiration today, is the one he painted of Pope Innocent X. Painted on his second trip to Italy, the artist was at the peak of his fame and technique.

It was not easy for the Pope to pose for a painter, it was a privilege that very few got. For Enriqueta Harris, the paintings that Velázquez brought her as a gift from the king must have put Innocent in a good mood.

He was inspired by the portrait of Julius II that Raphael painted around 1511, and by Titian's interpretation of it in the portrait of Pope Paul III, both very famous and copied. Velázquez paid homage to his admired Venetian master in this painting more than any other, although it is an independent creation: the upright figure in his chair is very powerful.