Democracy

La democracy (from the late Latin democratĭa, and this from the Greek δημοκρατία dēmokratía) is a form of social and political organization that attributes ownership of power to the citizenry as a whole. In a strict sense, democracy is a type of State organization in which collective decisions are adopted by the people through mechanisms of direct or indirect participation that confer legitimacy to their representatives. In a broad sense, democracy is a form of social coexistence in which members are free and equal and social relations are established according to contractual mechanisms.

Democracy can be defined from the classification of forms of government made by Plato, first, and Aristotle, later, into three basic types: monarchy (government by one), aristocracy (government "by the best" for Plato, "of the few" for Aristotle), democracy (government "of the multitude" for Plato and "of the many" for Aristotle).

There is indirect or representative democracy when political decisions are made by people recognized by the people as their representatives.

There is participatory democracy when a political model is applied that facilitates citizens' ability to associate and organize themselves in such a way that they can exert a direct influence on public decisions or when broad consultative plebiscite mechanisms are provided to citizens.

Finally, there is direct democracy when decisions are made directly by the members of the people, through plebiscites and binding referendums, primary elections, facilitation of the popular legislative initiative and popular voting on laws, a concept that includes liquid democracy.

These three forms are not exclusive and are usually integrated as complementary mechanisms in some political systems, although one of the three forms always tends to have a greater weight in a specific political system.

Do not confuse the republic with democracy, since they allude to different principles. According to James Madison, one of the founding fathers of the United States: "The two great points of difference between a democracy and a republic are: first, the delegation of government, in the latter, to a small number of elected citizens for the rest; secondly, the largest number of citizens, and the largest sphere of the country, over which the latter can extend."

Origin and etymology

The term democracy comes from ancient Greek (δημοκρατία) and was coined in Athens in the V century BCE. C. from the words δῆμος (dḗmos, which can be translated as "people") and -κρατία -kratía, from the root of κράτος (krátos, which can be translated such as "strength", "dominion", or "power").

However, the etymological meaning of the term is possibly much more complex. The term "demos" seems to have been a neologism derived from the fusion of the words demiurges (demiurgi) and geomoros (geomori). Theseus divided the free population of Attica (in addition, the population was also made up of metics, slaves and women). The Eupatrids were the nobles, the Demiurges were the artisans, and the Geomors were the peasants. These last two groups, "in increasing opposition to the nobility, formed the demos". Textually then, "democracy" would mean, always according to Plutarch, the "government of the artisans and peasants", expressly excluding slaves and peasants from it. nobles.

Some thinkers regard Athenian democracy as the first example of a democratic system. Other thinkers have criticized this conclusion, arguing on the one hand that examples of democratic political systems exist in both tribal organization and ancient civilizations around the world, and, on the other hand, that only a small minority of 10% of the population he had the right to participate in the so-called Athenian democracy, automatically excluding the majority of workers, peasants, slaves and women.

However, the meaning of the term has changed several times over time, and the modern definition has evolved a lot, especially since the turn of the century XVIII, with the successive introduction of democratic systems in many nations and especially from the recognition of universal suffrage and women's vote in the XX. Existing democracies today are quite different from the Athenian system of government from which they inherit their name.

History

Democracy first appears in many of the ancient civilizations that organized their institutions on the basis of tribal community and egalitarian systems (tribal democracy).

Among the best-known cases are the relatively brief experience of some ancient Greek city-states, notably Athens around 500 B.C. C. The small dimensions and the scarce population of the polis (or Greek cities) explain the possibility that an assembly of the people appeared, of which only free men could be a part, thus excluding 75% of the population made up of slaves., women and foreigners. The assembly was the symbol of Athenian democracy. In the Greek democracy there was no representation, government positions were held alternately by all citizens and the sovereignty of the assembly was absolute. All these restrictions and the small population of Athens (about 300,000 inhabitants) made it possible to minimize the obvious logistical difficulties of this form of government.

In 12th century America the Haudenosaunee Democratic and Constitutional League was formed, comprising the Seneca, Cayuga, and, Oneida, Onondaga and Mohicanos, where the principles of limitation and division of power were enshrined, as well as the democratic equality of men and women. Haudenosaunee democracy has been considered by various thinkers as the most direct antecedent of modern democracy.

During the European Middle Ages, the term "urban democracies" was used to designate commercial cities, especially in Italy and Flanders, but in reality they were governed by an aristocratic regime. There were also some so-called peasant democracies, such as that of Iceland, whose first Parliament met in 930, and that of the Swiss cantons in the 13th century. At the end of the XII century, the Cortes of the Kingdom of León (1188), initially called «town hall», were organized on democratic principles. because it brought together representatives of all social classes. In writers such as Guillermo de Ockham, Marsilio de Padua and Altusio, conceptions of the sovereignty of the people appear, which were considered revolutionary and which would later be collected by authors such as Hobbes, Locke and Rousseau. In Europe, this Republic of the Two Nations with a commonwealth political system, called Democracy of the Nobles or Golden Liberty, was characterized by the limitation of the power of the monarch by the laws and the legislative chamber (Sejm) controlled by the Polish Nobility (Szlachta). This system was the forerunner of the modern concepts of democracy, constitutional monarchy, and federation.

In Europe, Protestantism fostered a democratic reaction by rejecting the authority of the pope, although on the other hand, it strengthened the temporal power of princes. From the Catholic side, the School of Salamanca attacked the idea of the power of kings by divine design, defending that the people were the recipient of sovereignty. In turn, the people could retain sovereignty for themselves (democracy being the natural form of government) or voluntarily cede it to be governed by a monarchy. In 1653 the Instrument of Government was published in England, where the idea of limiting political power by establishing guarantees against possible abuse of royal power was enshrined. From 1688 the triumphant democracy in England was based on the principle of freedom of discussion, exercised above all in Parliament.

In America, the revolution of the commoners of Paraguay in 1735 upheld the democratic principle elaborated by José de Antequera y Castro: the will of the community is superior to that of the king himself. For their part, in Brazil, the Afro-Americans who managed to escape from the slavery to which they had been reduced by the Portuguese, organized themselves into democratic republics called quilombos, such as the Quilombo de los Palmares or the Quilombo de Macaco.

The independence of the United States in 1776 established a new ideal for democratic grassroots political institutions and became the first modern democracy, expanded by the French Revolution of 1789 and the Spanish-American War of Independence (1809-1824), spreading liberal ideas, human rights specified in the Virginia Declaration of Rights and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, constitutionalism and the right to independence, principles that constituted the ideological basis on which the entire Political evolution of the 19th and XX. The sum of these revolutions is known as the bourgeois Revolutions.

The constitutions of the United States of 1787 with the amendments of 1791, Venezuela of 1811, Spain of 1812, France of 1848, and Argentina of 1853 already have some democratic characteristics, which will record complex advances and setbacks. English democratic evolution was much slower and was manifested in the successive electoral reforms that took place from 1832 and culminated in 1911 with the Parliament Act, which established the definitive supremacy of the House of Representatives. Common over that of the Lords.

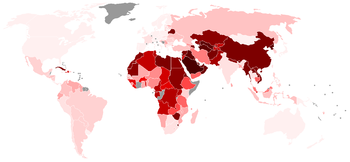

In reality, one can only speak of the progressive appearance of democratic countries from the XX century, with the abolition of the slavery, the conquest of universal suffrage, the recognition of legal equality for women, the end of European colonialism, the recognition of workers' rights and guarantees of non-discrimination for racial and ethnic minorities.

Types of democracy

Classically, democracy has been divided into two main forms: direct and representative.

Indirect or representative democracy

It is one where citizens exercise political power through their representatives, elected by vote, in free and periodic elections.

Semi-direct or participatory democracy

In this, the people express themselves directly in particular circumstances, basically through four mechanisms:

- Referendum. The people choose “on their own or not” on a proposal.

- Plebiscite. The people grant or do not grant the final approval of a rule (constitution, law, treaty).

- Popular initiative. By this mechanism a group of citizens may propose the sanction or annulment of a law.

- Popular dismissal, revocation of mandate or recall. Through this, citizens can dismiss an elected representative.

Direct democracy

This is democracy in its purest form, as lived by its Athenian founders, as practiced in Switzerland. Decisions are made by the sovereign people in assembly. There are no representatives of the people, but, in any case, delegates who become spokespersons for the people, who only issue the assembly mandate. It is the type of democracy preferred not only by the democrats of Ancient Greece, but also by many modern thinkers such as Rousseau.

Liquid democracy

Liquid Democracy is a kind of direct democracy in which each citizen has the possibility to vote on each decision of parliament and make proposals, but can give their vote to a representative for those decisions in which they prefer not to participate.

Practical application

In practice, there are many variants of the concept of democracy, some of them implemented in reality and others only hypothetical. Currently the most widespread mechanisms of democracy are those of representative democracy; in fact, it is the most used system of government in the world. Some countries, such as Switzerland or the United States, have some mechanisms typical of direct democracy. Deliberative democracy is another type of democracy that places the emphasis on the process of deliberation or debate, and not so much on voting. The concept of participatory democracy proposes the creation of direct democratic forms to attenuate the purely representative character (public hearings, administrative appeals, ombudsman). The concept of social democracy proposes the recognition of civil society organizations as political subjects (economic and social councils, social dialogue).

These differentiations are not presented in a pure form, but democratic systems tend to have components of both forms of democracy. Modern democracies tend to establish a complex system of control mechanisms for public office. One of the manifestations of these horizontal controls is the figure of the impeachment process or "political trial", to which both presidents and judges can be subjected, by parliaments, in accordance with certain constitutions, such as that of Argentina, Brazil or United States. Other more modern agencies aimed at the same purpose are the ombudsman or ombudsman, public company syndicates, auditing bodies, public ethics offices, etc.

Finally, it should be noted that there is an increasingly relevant current in the Anglo-Saxon world that advocates combinations of current institutions with democratic applications of lottery. Among the most relevant authors of this current, we can mention John Burnheim, Ernest Callenbach, A. Barnett and Peter Carty, Barbara Goodwin or, in the French sphere, Yves Sintomer. The established authors who have devoted more space to this type of proposal are Robert A. Dahl and Benjamin Barber. In the Spanish-speaking world, the reception is still very low, although authors such as Juan Ramón Capella have raised the possibility of going to the raffle as a democratizing tool.

Components of democracy

In modern democracy, the so-called majority rule plays a decisive role, that is, the right of the majority to have their position adopted when there are various proposals. This has made it a commonplace in popular culture to assimilate democracy with a majority decision. Elections are the instrument in which the majority rule is applied; thus making democracy the most efficient, effective and transparent exercise, where equality and the opportunity for justice are applied, a practice originating in the centuries XVIII and XIX; when the woman participates in the right to vote. Furthermore, contemporary democracy does not remain parallel to the absolutist regime and the monopoly of power.

However, many democratic systems do not use majority rule or restrict it through rotating election systems, at random, the right to veto (special majorities), etc. In fact, in certain circumstances, the majority rule can become undemocratic when it affects the fundamental rights of minorities, individuals or violates the fundamental principles of the life of the State, issues that we will know as the sphere of what undecidable.

Real democracies are usually complex articulated mechanisms, with multiple rules of participation in deliberation processes, decision-making, in which power is divided constitutionally or statutorily, into multiple functions and territorial areas, and a variety of control systems, counterweights and limitations are established, which lead to the formation of different types of majorities, to the preservation of basic spheres for minorities and to guarantee the human rights of individuals and social groups. There is also a fundamental difference between the concept of democracy and democratization. The concept of democracy is connected to the capacity of the political class to respond to the needs of the population. Instead, the concept of democratization has to do with the ability of a society to adapt to the process of cultural, legal, and political homogenization that took place after the end of the Cold War.

This is why we must analyze what are the essential principles of democracy.

Democratic principles

Democracy must be understood as a political system among the different possibilities that have existed to configure States throughout history. That is, democracy is one of the political forms in which social coexistence can be organized, because just as a society can establish itself as a democracy, it can also do so as an Aristocracy or an Autocracy. Democracy entails the possibility that there are means of participation by the citizenry, that there are differences between the participants in said process and that conflicting opinions are expressed. In this way, it is affirmed that democracy repudiates the possibility that power is abrogated by a single person at their own and exclusive discretion, opening the seat of power to a plurality of people as well as to criticism and opposition by the members of society themselves.

From the above, we can infer certain principles without which it is not possible to affirm that a democracy exists, let's see.

Equality

Democracy recognizes the possibility that anyone can participate in the exercise of political power within a given State. For this reason, it is necessary to recognize the existence of equality among citizens, since, without it, the necessary means would not exist for participation and opposition to develop freely. In light of this, the door is opened to two paradigms that condition the development of democracy with regard to equality:

- Redistribution, with regard to the equal rights that every individual has with each other and with the State to participate in democratic processes.

- Recognition, with regard to the fact that not all participants of the democratic process are in factual circumstances equal, therefore our opinions will be differentiated from each other.

From this we obtain the ideals of equality and freedom, since, on the one hand, we have the possibility of a society being plural and with diverse needs and ideals about what is fair and, on the other hand, we have that the members of society – even when they do not have issues in common with each other – participate in the political entity that holds power under equal circumstances.

It is there that the essence of democracy is observed:

- The one who first recognizes the divergences between society itself, which is natural in the development of a life in freedom;

- Then, it is feasible that social divergences are freely expressed;

- Likewise, the possibility that not only such divergences are expressed, but also the mechanisms for such differences to reach the political entity that holds power and hence create conditions for social life, and

- All of the above in equal circumstances and without leaving any individual out of those means of access to the political entity that organizes life in society.

It is evident that, based on the assumption that all individuals who participate in political decision-making are equal –as regards our Right to participate–, the concept of democracy is born. That is, from the affirmation that any citizen has the possibility of participating in the political entity that will hold power, we obtain that the main feature of democracy, which is that the political will comes from those who are governed by it. This is the importance of the principle of equality, because, without it, it will not be possible to make individuals feel responsible for participating in decision-making within the political entity that holds power. Somehow, without the feeling of equality, individuals will not feel like members of the same community, so their sense of responsibility will be diminished, affecting the essence of the democratic State.

The limitation of power

You must guarantee said possibility of access; that is, individuals must enjoy a series of conditions that favor our participation in the political entity that holds power, which can only be developed when the aforementioned democratic precursors exist.

It has been affirmed that Democracy, for the purpose of guaranteeing the minimum conditions for citizen participation, imposes limits on the public power in its exercise, which will tend to safeguard the interests and rights of individuals, and, in addition, determines the functions of the power itself and thus divides it; once this is done, institutions such as the Legislative, Executive and Judicial are created, and each branch is assigned a specific function of power, as well as powers and assumptions for its exercise. Somehow, in a democratic State, the limit of power is sought as a guarantee for citizens to participate in national politics, limits that can be identified as two types:

- From the State to the individual, which is guaranteed by the fundamental rights established by the Constitution in favour of the governorate;

- Of the State ' s own institutions among them, which is guaranteed by the division of power and the establishment of powers between them.

- Of individuals among themselves, which is achieved through the inclusion and regulation of so-called social rights.

According to this, the Constitution of a democratic State will have limits of both public and private power vis-à-vis individuals and the very institutions that make up the State; In this way, on the one hand, it is avoided that individuals are deprived of the necessary conditions for them to develop their lives and be in a position to participate in the national political entity, while, on the other hand, it prevents power from being find it concentrated in a single person or institution as it happens in autocratic states.

By limiting the power, it is guaranteed that there will be no abuses in the exercise of it. In accordance with this, individuals may enjoy their own conditions for the free exercise of their individual rights. In addition, political power is also prevented from concentrating in a single institution or person, which would be pernicious since this single person does not have a global vision of social needs and, on the other hand, could exercise their power without any limitation, including on any individual right.

The sphere of the undecidable

The Constitution of a democratic State recognizes the possibility that all the members of society participate in the decision of how the new political entity will be configured. This derives from the interference of the real factors of power in decision-making at the origin of the life of the State. Somehow, the decisions made by the real factors of power when having decided the course that the State would take are the principles that will govern its sociopolitical development.

These are called the fundamental political decisions, since all the factual powers that govern in a certain place and moment will erect the superior principles that will characterize the political-legal system of their community. For example, in a determined In a democratic state it may be decided that economic development is focused on the creation of productive state companies, while in another state a liberal development of such issues could be opted for. Such ideals will be known as fundamental political decisions and, as we will see, they will be part of the sphere of the undecidable.

As seen in other sections, a democracy is based on various principles, such as the division of power, equality or respect for fundamental rights. Thus, these same democratic principles cannot be ignored by any person or institution, including majorities.

That's right, there are certain principles of the Democratic State that cannot be reduced by the actions of the institutions themselves that have been constituted in the light of Democracy and, furthermore, they cannot be forgotten by the democratic majorities even when they do so. so determined through the processes and mechanisms established in the Constitution. According to this postulate, a "sphere of the undecidable" is constituted, which contain fundamental political and legal decisions that cannot be subject to any limitation by a majority.

For this reason, it is feasible to make a differentiation between formal and material democracy. On the one hand, it can be considered that a democratic decision taken by a majority is formally valid if it is taken in accordance with the procedure that a democratic State established in its Constitution; but, on the other hand, this is not enough to consider that said decision is also materially valid, since this depends on its content being in accordance with the fundamental principles adopted in the Constitution by all the members of the company.

The acts of the majorities, even when they have been created in accordance with the formal regulations of Democracy, may be invalid for transgressing what we have called the sphere of the undecidable: substantial Democracy, also known as material. The norms and acts of authority must not only adjust to democratic procedures, but must also contain minimum criteria in light of essential concepts of the State.

This constitutional principle seeks to prevent the democratic problem known as "tyranny of majorities" and that later is developed.

Control of power

Finally, it is recognized that a democratic State cannot subsist if there are no tools that guarantee the regularity of acts of authority with the essence of the State.

According to this, the control of the constitutionality of the acts becomes an axis of constitutional effectiveness, reinforcing the mandatory nature of the Constitution itself and the fundamental political decisions that were taken there and providing balance to the fundamental rights and institutional structures determined by the constitutional agreement. Then, the means of control of constitutionality are identified as the legal resources designed to verify the correspondence between the acts issued by those who hold power and the Constitution, annulling them when those violate constitutional principles, in this way the nature of correction of the means of control, so they destroy acts already issued. It is because of this characteristic by virtue of which we can affirm that the rights and principles contained in the Constitution -which turns out to be the political pact par excellence of a democracy- acquire the nature of a legal norm, specifically a rule, which can be opposable against all those acts that challenge it, acquiring unwavering firmness by invalidating all those acts that transgress its essence. Given this, the fundamental principles adopted in a democratic State become enforceable.

Classes of democracies

It is not feasible to consider that all democracies are equal. The creation of a democratic State derives from the decision of the people, so the way in which this will be regulated will depend on the interests of those who turn out to be the real factors of power at the time and place in which the decision has been made for the democratic regime.. For this reason, we have seen throughout modern political history the creation of various kinds of democratic models such as those listed below.

Liberal democracy

In many cases the word "democracy" is used as a synonym for liberal democracy. Liberal democracy is usually understood as a generic type of State that emerged from the Independence of the United States in 1776 and then more or less generalized in the republics and constitutional monarchies that emerged from the emancipation or revolutionary processes against the great absolute monarchies and established systems of government. in which the population can vote and be voted, while the right to property is preserved.

Thus, although the term «democracy» strictly refers only to a system of government in which the people hold sovereignty, the concept of «liberal democracy» supposes a system with the following characteristics:[ citation required]

- A constitution that limits the various powers and controls the formal functioning of the government, and thus constitutes a rule of law.

- Power division.

- The right to vote and be voted in elections for a broad majority of the population (universal vote).

- Protection of the right of ownership and existence of important private groups of power in economic activity. Sustained[chuckles]Who?] that this is the essential characteristic of liberal democracy.

- Existence of several political parties (not single party).

- Freedom of expression.

- Freedom of the press, as well as access to sources of information alternative to those of the government that guarantee the right to information of citizens.

- Freedom of association.

- Human rights monitoring, including an institutional framework for the protection of minorities.

Based on the foregoing, some scholars[who?] have suggested the following definition of liberal democracy: the rule of the majority with rights for minorities.[citation needed]

In this regard, this type of democracy has some particularities that distinguish it from other forms of democracy, including the free confrontation of ideas. In the words of Pío Moa:

- () Liberalism makes it possible to expose all ideas, but the confrontation between them must facilitate precisely the overcoming of the false or destructive and the reaffirmation of the best founded, in an endless process. That is why confrontation is indispensable, and a good way to avoid physical shocks.()

Social Democracy

Social democracy is a version of democracy in which state regulation and the creation of state-sponsored programs and organizations are used to attenuate or eliminate social inequalities and injustices that, according to their defenders, they would exist in the free economy and capitalism. Social democracy is basically based on universal suffrage, the notion of social justice and a type of State called the Welfare State.

Social democracy arose at the end of the 19th century out of the socialist movement, as a alternative, peaceful and more moderate proposal to the revolutionary form of taking power and imposing a dictatorship of the proletariat, which was supported by a part of the socialist movement, giving rise to a debate around the terms "reform" and "revolution"..

In general, the system of government that predominates in the Scandinavian countries, the so-called Nordic welfare model, has been presented as a real example of social democracy.

Democracy as a system of horizontal relations

The term «democracy» is also widely used not only to designate a form of political organization, but a form of coexistence and social organization, with more egalitarian relations among its members. In this sense, the use of the term "democratization" is common, such as the democratization of family relations, labor relations, the company, the university, the school, culture, etc., such exercises are basically oriented to the field of citizen participation, whose main mechanisms used for such purposes are elections through popular vote, assemblies, project proposals and all those in which the will for changes or approvals is channeled with the direct participation of the different social groups..[citation required]

Democracy in constitutional monarchies

Two special cases for the idea of democracy are constitutional monarchies and popular democracies that characterize real socialism.

The constitutional monarchy is a form of government that characterizes several countries in Europe (Great Britain, Spain, the Netherlands, etc.), America (Canada, Jamaica, etc.), and Asia (Japan, Malaysia, etc.).

Constitutional monarchies vary widely from country to country. In the United Kingdom, current constitutional provisions grant certain formal powers to the king and nobles (appointment of the prime minister, appointment of rulers in Crown dependencies, suspensive veto, court of last resort, etc.), in addition to the powers informal derivatives of their positions.

There is a general trend towards the progressive reduction of the power of kings and nobles in constitutional monarchies that has been accentuated since the last century XX. Although, because they are monarchies, in these countries there is notable inequality before the law and in fact of kings and other nobles compared to the rest of the population, the severe restriction of their government and judicial powers has led to their participation in most acts of government is exceptional and highly controlled by other powers of the State. This has given rise to the expressive popular saying that kings "reign but do not govern" to refer to the weak legal influence that kings and eventually nobles have in daily government acts.

In the Kingdom of Spain, the King promulgates laws, convenes and dissolves the Cortes Generales, convenes a referendum, proposes and removes the President, exercises the right of pardon and commutation of sentences, declares war, makes peace, etc. In the exercise of all his functions, the King acts as a mediator, arbitrator or moderator, but without assuming responsibility for his acts that must be endorsed by the executive or legislative power, which makes him a representative figure of the state but no political power. The king also enjoys inviolability and, like many other republican heads of state, he cannot be tried for any crime.

Opponents of constitutional monarchies argue that they are not democratic, and that a system of government in which citizens are not all equal before the law, while the head of state and other state officials cannot be elected, cannot be called democracy, although in Spain the monarchy is not constitutional but parliamentary. The defenders, on the other hand, defend that it does not have to be democratic; loaded with ideologies. It is better for the head of state to be an impartial person than someone loaded with ideologies; and that, since his position is for life, he will not commit acts for electoral purposes.

People's Democracy

Representativeness model based on the experience of the Paris Commune and on the improvement in the degree of representativeness of liberal Democracy. This direct Democracy starts from the daily work places, where representatives are elected in each factory, workshop, farm or office, with a revocable mandate at any time. These delegates form a local Assembly (soviets) and then send their representative to the National Assembly of People's Delegates.

The 10% of the population that includes businessmen, bankers and landowners, who already possess economic power, are denied the vote and political power.[citation required] That is why it is said that it is Workers' Democracy or dictatorship of the proletariat, since political power is applied against the established economic power.

This new State must be established by the insurrection of the masses, guided by a single party or multi-party front if possible, with a party line that aims to sweep away the institutions of the bourgeois State and the legality that ensures economic power of the minority. The conscious revolutionary elite has the objective of instructing society in the ways of self-government, urges to elect its delegates in the workplaces, committees of factories, farms and workshops, through which they will learn to manage the economy, transforming into everyday citizenship and permanent power.

The feasibility of eliminating the conditions of bourgeois existence is discussed, supposed for the transition from alienated to communist society. This means that as progress is made in the socialization of political power and economic power the "withering away of the State" will take place, becoming only an administrative structure under the control of all citizens. This "non-state" is considered the final stage of socialism: communism.

Democracy in real socialism

Countries with political systems inspired by Marxist communism known as "real socialism" such as Cuba have systems of government that often use the name of "popular democracies." The so-called "popular democracies" are characterized by being organized on the basis of a single or hegemonic political party system, closely linked to the State, in which, according to their promoters, the entire population can participate and within which the representation of the different political positions, or at least most of them allowed by the State. On the other hand, in the current so-called "popular democracies", freedom of expression and of the press are restricted and controlled by the State.

According to its defenders, «popular democracy» is the only type of democracy in which the economic, social and cultural equality of citizens can be guaranteed, since private economic powers cannot influence the system of representation.

Some Marxists also believe that the current "people's democracies" are not true socialist democracies and that they constitute a distortion of the original principles of Marxism. In the specific case of China, they maintain that it has developed an economy oriented towards capitalism, but it uses its title of "People's Democratic Republic" to be able to count on cheap labor, through the exploitation of Chinese workers, up to living standards. classified as subhuman, as happens in many capitalist democracies.

Democracy and human rights

By human and citizen rights we mean the set of civil, political and social rights that are at the base of modern democracy. These reach their full affirmation in the XX century.

- Civil rights: individual freedom, expression, ideology and religion, right to property, to close contracts and to justice. Affirmed in the centuryXVIII.

- Political rights: right to participation in the political process as a member of a body to which political authority is granted. Affirmed in the centuryXIX.

- Social rights: freedom of association and the right to a minimum economic well-being and a decent life, according to the prevailing standards in society at every historical moment. Affirmed in the centuryXX..

A distinction has also been made between first (political and civil), second (socio-labour), third (socio-environmental) and fourth generation (participatory) human rights.

Democracy, control mechanisms and horizontal accountability

Guillermo O'Donnell has highlighted the importance of control mechanisms or horizontal accountability, in modern democracies, which he prefers to call «polyarchies». Horizontal control differs from democratic vertical control that is carried out through periodic elections, visualized as a conformation of the State, made up of various agencies with the power to act against the illegal actions or omissions carried out by other State agents.

Modern democracies tend to establish a complex system of control mechanisms for public office. One of the manifestations of these horizontal contrales is the figure of the impeachment process or "political trial", to which both presidents and judges can be subjected, by parliaments, in accordance with certain constitutions, such as that of Argentina, Brazil or United States. Other more modern agencies aimed at the same purpose are the ombudsman or ombudsman, public company syndicates, auditing bodies, public ethics offices, etc.

Issues related to democracy

Transition and democratic culture

In those countries that do not have a strong democratic tradition, the introduction of free elections alone has rarely been enough to successfully carry out a transition from dictatorship to democracy. It is also necessary to produce a profound change in the political culture, as well as the gradual formation of the institutions of democratic government. There are several examples of countries that have only been able to maintain democracy in a very limited way until profound cultural changes have taken place, in the sense of respect for majority rule, essential for the survival of a democracy.

One of the key aspects of democratic culture is the concept of "loyal opposition." This is a cultural change that is especially difficult to achieve in nations where changes in power have historically occurred violently. The term refers to the fact that the main actors participating in a democracy share a common commitment to its basic values, and that they will not resort to force or to mechanisms of economic or social destabilization, to obtain or recover power.

This does not mean that there are no political disputes, but always respecting and recognizing the legitimacy of all political groups. A democratic society should promote tolerance and civilized public debate. During the different elections or referendums, the groups that have not achieved their objectives accept the results, because they conform to their wishes or not, they express the preferences of the citizens.

Especially when the results of an election lead to a change of government, the transfer of power must be carried out in the best possible way, putting the general interests of democracy before those of the losing group. This loyalty refers to the democratic process of change of government, and not necessarily to the policies put into practice by the new government.

The process of global expansion of representative institutions between the mid-1970s and the end of the XX century, known as the Third Wave of Democratization as Samuel Huntington (1991) called it, produced a considerable number of hybrid regimes and long-lasting democracies but of less than optimal quality. This balance did not conform to the initial expectations of many political scientists and questioned some of the assumptions of transitology, the theoretical paradigm that had predominated in analyzes of the democratic wave. One of these assumptions was that the viability of democracy did not depend on the existence of specific cultural patterns rooted in society, but mainly from the rationality of political actors.

The problem of the quality of new democracies generated renewed interest in political culture, an approach that had emerged in the early 1960s with the pioneering studies of Gabriel Almond, Sidney Verba, Harry Eckstein and others. The dissemination of transnational surveys, such as the World Values Survey, the European Social Survey and regional Barometers, as well as case studies, have fueled the progress of this trend. Empirical research since the 1980s, including the work of Ronald Inglehart, Robert D. Putnam, and Christian Welzel, suggests that a defined system of values, beliefs, and habits appears to be essential for stability, depth, and and effectiveness of democracy.

This converging set of theories, hypotheses and models underlines the influence exerted on the quality of new democracies by cultural traits such as “emancipatory values” or “self-expression”, “social capital” or “civic community”, the population support for the democratic system and trust in institutions. Among the specific elements of culture, respect for others, aspirations for freedom, gender equality, interpersonal trust, autonomous political participation and insertion in voluntary organizations with objectives that benefit the whole of society would play a critical role. society.

Democracy and Republic

The differences and similarities between the concepts of «democracy» and «republic» give rise to several common confusions and differences of criteria among specialists.

In general, it can be said that the republic is a type of government in which the participation of different people in the exercise of political power is allowed, which prevents the same person from occupying a seat in power. For its part, democracy is a system in which political power emanates from the people and entails various principles such as the division of power, control of power and equal treatment among members of society.

A republic may not be democratic, when large groups of the population are excluded, as happens with electoral systems not based on universal suffrage, or where there are racist systems that, although they allow the transition of power to different people, are unaware of principles such as equality, participation and the possibility of expressing opposition by any person in society.

Democracy and Autocracy

- Democracy: Participation of the people in the creation of laws. Power is formed from the bottom up, that is, from the people.

- Autocracy: Citizens do not participate freely in the creation of laws. Power is constituted from top to bottom, that is, from the governor or the group that governs.

Democracy and poverty

There seems to be a relationship between democracy and poverty, in the sense that those countries with higher levels of democracy also have a higher GDP per capita, a higher human development index and a lower poverty index.

However, there are disagreements about the extent to which democracy is responsible for these achievements. However, Burkhart and Lewis-Beck (1994) using time series and rigorous methodology have found that:

- Economic development leads to the emergence of democracies.

- Democracy alone does not help economic development.

The subsequent investigation revealed the material process by which a higher level of income leads to democratization. Apparently a higher level of income favors the appearance of structural changes in the mode of production that in turn favor the appearance of democracy:

- A higher level of income favors higher educational levels, creating a more articulated, better informed and better prepared audience for the organization.

- A higher level of development favors a higher degree of occupational specialization, this first produces the favor of the secondary sector versus the primary and tertiary compared to the secondary sector.

The assertion that economic development leads to the emergence of democracies has also received some critics, who maintain that it would be a spurious relationship. Rather than leading directly to democracy, economic development would have produced transformations in the class structure of capitalist society, which have made possible a progressive democratic stabilization in the world in the last 150 years, but economic development has not led to democracy elsewhere. previous periods of history. Likewise, even in the XX century, some regions such as Latin America experienced setbacks in democracy amid processes of modernization and expansion economic.

A leading economist, Amartya Sen, has pointed out that no democracy has ever experienced a major famine, including democracies that have not been very prosperous historically, such as India, which had its last major famine in 1943 (and which some associate with the effects of the First World War), and yet it had many others in the 19th century, all under British rule. [citation required]

Economic Democracy

The term economic democracy is used in economics and sociology to designate those organizations or productive structures whose decision-making structure is based on the unitary vote (one person = one vote, or democratic rule), contrary to what is produced by private companies typical of a capitalist nature, where the plural vote weighted by the participation in the capital prevails (one share = one vote). The typical example of a democratic company is the cooperative, one of whose cooperative principles is precisely the democratic principle of decision. The example of democratization of the economy applied on a larger scale was the councils of workers and consumers instituted in the Soviet Union.

Arguments for and against democracy

Fundamental functions of a State

For the IDB, democracy is an essential requirement for the State to:

- Stabilize the economy with high levels of economic growth and employment, and moderate inflation.

- Mitigate vertical and horizontal balances.

- Be efficient in resource allocation and service delivery.

- Control the predatory actions of the public and private sectors through the preservation of public order, the control of abuses and arbitrariness, and the prevention of corruption. These functions are vital to foster sustainable growth and reduce poverty.

Distortions

Democracy is a form of government in which decision-making is legitimized by a rational basis. A common criticism is its weakness in the face of unbalanced influences on decision-making (known as "authoritarian democracies", since which authority is the legitimized power) masked under this legitimation, generating other structures such as:

- Plutocracy: in this there are unbalanced influences in decision-making in favor of those who possess the sources of wealth. For example, through inadequate funding of campaigns and political parties.

- Partitocracy: for example because of a misguided parliamentary system, instead of a presidential or semi-presidenial one or through the influence of political parties on a representative elected by citizenship.

- Oclocracy: for example by the existence of popular ignorance or a powerful demagogic action. To avoid this, some authors consider that a fourth power, the media, should be treated within the concept of separation of powers.

Ignorance of citizenship

One of the most common criticisms of democracy is the one that alleges an ignorance of citizens about fundamental political, economic and social aspects in a society, which disables them to choose between the various proposals. This system was called by Polybius as ochlocracy. This ignorance would mean that the decisions made by different sectors were wrong in most cases, as they were not based on technical knowledge.

The philosopher Socrates believed that democracy without educated masses (educated in the broadest sense of being knowledgeable and responsible) would only lead to populism as a criteria for becoming an elected leader and not a competition. This would ultimately lead to the demise of the nation. This was quoted by Plato in book X of The Republic, in Socrates' conversation with Adeimantus. Socrates was of the opinion that the right to vote should not be an indiscriminate right, but should be granted only to people who thought enough about their choice.

This argument is also often cited by politicians to discuss the results of referendums and legitimate elections and also in contexts in which reforms are proposed in search of a deepening towards forms of democracy that are more participatory or direct than representative democracy. On the other hand, there are documents (religious, philosophical, theoretical, academic) that mention the political and ruling class as responsible for the ignorance of citizens to achieve personal or elitist goals. In order to avoid this circumstance, there are laws that make it compulsory to dedicate part of the government patrimony to provide information to the population through official bulletins on the new laws or through the publication of sentences on judicial decisions or through campaigns to the population before a referendum is held. all of them great noble judicial conquests that seek to maintain social and economic peace, leaving a clear legal framework that defends all citizens from tyranny.

In some countries it is known that ignorance translates into abstention in elections, in countries where all its citizens are forced to vote ignorance can seriously affect (or not) the outcome of the elections.

Several tendencies on the left tend to proclaim electoral abstentionism, since they see voting as a "lie" for the people.

Although for the purposes of quantifying the degree of popular ignorance through abstention, it is considered that abstention collects both the votes of those who say they are unaware of political issues (apolitical) and those who are not satisfied with the system in yes or none of the candidates or parties that are presented, so it is often difficult to distinguish between abstention due to ignorance and abstention due to protest .

The tyranny of the majority

The majority rule on which democracy is based can produce a negative effect known as tyranny of the majority, not to be confused with Ochlocracy. It refers to the possibility that in a democratic system a majority of people can theoretically harm or even oppress a particular minority. This is negative from the point of view of democracy, since it tries to give the citizenry as a whole more power.

Here are some real-life examples in which a majority acts or has acted in the past in controversial ways against the preferences of a minority on specific issues:

- The treatment of society towards homosexuals is often cited in this context. An example is the criminalization of homosexuals in Britain during the centuryXIX and part of XX., being famous the persecutions to Oscar Wilde and Alan Turing.

- Some think that drug users are a minority oppressed by the majority in many countries, by criminalizing drug use. In many countries, drug-related prisoners lose their right to vote.

- Athenian democracy condemned Socrates for impiety, that is, for dissent, although the relevance of this fact in the face of modern democracies is controversial.

- In France, there are those who believe that the current prohibitions on the display of personal religious symbols in public schools are a violation of the rights of religious persons.

- In the United States:

- The age of enlistment for the Vietnam War was criticized for being an oppression of a minority who had no right to vote, those aged 18 to 21. In response to this, the age of enlistment rose to 19 years and the minimum age for voting was lowered. Although they could already vote, those persons subject to enlistment remained a minority that could be considered oppressed.

- The distribution of pornography is illegal if the material violates certain "standards" of decency.

Los defensores de la democracia exponen una serie de argumentos como defensa a todo esto. Uno de ellos es que la presencia de una constitución actúa de salvaguarda ante una posible tiranía de la mayoría. Generalmente, los cambios en estas constituciones requieren el acuerdo de una mayoría cualificada de representantes, o que el poder judicial avale dichos cambios, o incluso algunas veces un referéndum, o una combinación de estas medidas. También la separación de poderes en poder legislativo, poder ejecutivo y poder judicial hace más difícil que una mayoría poco unánime imponga su voluntad. Con todo esto, una mayoría todavía podría discriminar a una minoría, pero dicha minoría ya sería muy pequeña (aunque no por ello dicha discriminación deja de ser éticamente cuestionable).

Another argument is that a person tends to agree with the majority on some issues and disagree on others. And also the postures of a person can change. Therefore, members of a majority can limit oppression towards a minority since they themselves may in the future be part of an oppressed minority.

There are also those who affirm that democracy must deal with objective issues, since this kind of “oppression” is subjective since it is subject to the feelings or thoughts of a few and that generally do not go beyond triviality.

A final common argument is that, despite the risks discussed, majority rule is preferable to other systems, and in any case "tyranny of the majority" is an improvement over "tyranny of a minority". Defenders of democracy argue that empirical statistics clearly show that the greater the democracy, the lower the level of internal violence. This has been formulated as "Rummel's law," which holds that the lower the level of democracy, the more likely rulers are to murder their own citizens.

Hitler and democracy

A critique of democracy, itself derived from a historical misunderstanding, is the claim that democracy prompted Adolf Hitler's rise to power when he was democratically elected as president of the Weimar Republic in 1933.

The historical facts are that in 1932 Hitler lost the presidential elections against Paul von Hindenburg, who obtained 53% against 36% of that one. In the parliamentary elections of July of the same year, Hitler's Nazi Party reached 230 seats, making it the most numerous. At that moment, President Hindenburg offers Hitler the vice chancellorship, but he rejects it; However, the Nazis made an alliance with the forces of the center in the government, as a result of which, Hermann Goering, one of Hitler's main collaborators, was elected president of the parliament (Reichstag).[citation required]

In November 1932 there were new parliamentary elections in which the Nazi Party lost two million votes and the bloc was reduced to 196 seats. The electoral crisis of the center-right alliance led to the resignation of Chancellor Franz von Papen. Hindenburg then thinks of offering the chancellorship to Hitler, but faced with the opposition of the army he appoints General Kurt von Schleicher as chancellor. This manages to further weaken Hitler who suffers a new electoral defeat in the regional elections in Thuringia. In this situation, the socialist and communist benches withdraw their support from Schleicher, forcing him to resign in January 1933. Hindenburg again oscillates between von Papen and Hitler, deciding on the former. But he does not get to assume because the SA (Sturmabteilung), the paramilitary force of Nazism led by Ernst Röhm, take military control of Berlin. Under these conditions Hindenburg appointed Hitler Chancellor on January 30, 1933. Hitler then dissolved Parliament and called elections for March 5. In the meantime, the Reichstag was burned, which Hitler took advantage of to annul constitutional guarantees, imposed the death penalty to apply to those who carried out "serious disturbances of the peace", and placed his men in the leadership of the army.. In these already dictatorial conditions, the elections were held in which he obtained 44% of Parliament, a number that did not grant him a majority either. By then the dictatorship had already been definitively installed, and Parliament no longer had political influence.

In addition, the current constitution in that context allowed the establishment of dictatorial powers and the suspension of the majority of the constitution itself in case of “emergency”, without any type of vote, something unthinkable in most modern democracies. In any case, it is important to note that the largest human rights violations took place after Hitler completely abolished the democratic system.

Marxist critique of "bourgeois democracy"

Within the Marxist conception under historical materialism, the State is the organ of society for the maintenance of social order at the service of the ruling class. Bourgeois democracy is exercised as a dictatorship of the bourgeoisie over the proletariat. Capitalist society is founded on human exploitation, the theft of human labor through the concept of "plus value", legitimized in private property. Therefore, the bourgeois State cannot be a defender of the general interests, since these are opposed to those of private property. On the contrary, the dictatorship of the proletariat is the dictatorship of the most numerous class that does not seek to sustain its situation of dominance but to make class antagonisms disappear. Only in communist society, when it has been broken when the capitalists have disappeared and there are no social classes, only then "will the State disappear and it will be possible to speak of freedom".

"Only then it will be possible and a truly complete democracy will come true, a democracy that truly does not involve any restrictions. And only then will democracy begin to become extinct, for the simple reason that men, freed from capitalist slavery, from the innumerable horrors, bestialities, absurdities and vilezas of capitalist exploitation [...] Therefore, in capitalist society we have an amputated, petty, false democracy, a democracy only for the rich, for the minority. The dictatorship of the proletariat, the period of transition to communism, will for the first time bring democracy for the people, for the majority, to the same time with the necessary repression of the minority, of the exploiters. Only communism can bring a truly complete democracy, and the more complete it is, before it ceases to be necessary and will be extinguished by itself. "Vladimir Lenin (1917), The State and the RevolutionChapter V, 2. The Transition from Capitalism to Communism

Also, Marx thought that universal suffrage would have as an «inevitable result […] the political supremacy of the working class»; however, he also believed that representative government, by giving officials broad powers, could undermine the emancipatory potential of the vote. In this way, he proposed —in order to immediately sanction the representatives— that the elections be more frequent and with revocable mandates at any time. Similarly, Marx supported the "imperative mandate" in which the population has direct influence over the legislative process. In addition, he criticized excessive executive power.

For his part, Mao Zedong argued that during the Chinese revolution a democracy that he called New Democracy preceded a second socialist stage.

Contenido relacionado

Monism

Hague

Papua New Guinea