Demiurge

The demiurge (in Greek: Δημιουργός, dēmiurgós) is the description of a deity who, in the idealist philosophy of Plato and in the mysticism of the Neoplatonists, was considered a creator god of the world and author of the universe; and which later in Gnostic philosophy derived into the entity that, without necessarily being a creator, is the promoter of the universe. "Demiurge" literally means 'master', 'supreme craftsman', 'maker'.

In the Platonic, Neopythagorean, Middle Platonic, and Neoplatonic schools of philosophy, the demiurge is a craftsman-like figure responsible for shaping and maintaining the physical universe. Gnostics later adopted the term "demiurge." Although the demiurge shapes the physical universe, this does not necessarily make him equal to the figure of the creator in the monotheistic sense, as the demiurge himself, as well as the material from which he shapes the universe, are considered both as consequences of something else. Depending on the system, the demiurge can be considered uncreated and eternal or the product of some other entity.

The word "demiurge" derives from demiurgus, a Latinized form of the Greek δημιουργός or dēmiurgós. It was originally a common noun meaning 'artisan', but gradually came to mean 'producer'. and finally 'creator'. Its philosophical use and its use as a proper name both derive from Plato's Timaeus, written around 360 B.C. C., where the demiurge is presented as the creator of the universe. The demiurge is also described as a creator in the Platonic (c. 310 BC-390 BC) and Middle Platonic (c. 90 BC-300) philosophical traditions. In the various branches of the Neoplatonic school (III century onwards), the demiurge is the one who shapes the real world and perceptible according to the model of Ideas, although (in most Neoplatonic systems) it is not yet in itself the One. In the arch-dualist ideology of the various Gnostic systems, the material universe is evil, while the immaterial world is evil. well. According to some currents of Gnosticism, the demiurge is malevolent, since he is linked to the material world. In others, including the teachings of Valentine, the demiurge is seen as simply being ignorant or confused.

Platonism and Neoplatonism

Plato

Allusions to the demiurge are found in numerous Platonic dialogues, from Gorgias to Philebus, passing through Cratylus, the Republic and the Sophist. In particular, Plato refers to the demiurge frequently in the Socratic dialogue Timaeus (28a ff.), written around 360 BC. C. The main character refers to the demiurge as the entity that "designed and shaped" to the material world. Timaeus describes the demiurge as entirely benevolent and therefore wants the best possible world. This work by Plato is a philosophical reconciliation of Hesiod's cosmology in his Theogony, reconciling Hesiod with Homer syncretically.

According to Plato's myth exposed in the Timaeus —a work in which he describes the disposition, based on reasoning based on the theory of ideas and the cosmos—, at the beginning in the universe there were only

- report and chaos;

- ideas, which are perfect;

- the demiurgo, a divinity;

- space.

Plato tells us that the demiurge takes pity on matter and copies ideas into it, thereby obtaining the objects that make up our reality. In this way he explained the separation between the world of ideas that are perfect and the real world (material) that, being imperfect, participates as a copy of perfection.

Middle Platonism

In the Neopythagorean and Middle Platonic cosmogony of Numenius, the demiurge is the second God as the nous or thought of the intelligible and sensible.

Neoplatonism

Plotinus and the later Platonists worked to clarify the notion of demiurge. For Plotinus, the second emanation represents a second uncreated cause (compare the Dyad of Pythagoras). Plotinus sought to reconcile Aristotle's energeia with Plato's demiurge, which, as demiurge and mind (nous), is a critical component in the ontological construct of human consciousness. which is used to explain and clarify the theory of substance within Platonic realism (also called idealism). To reconcile Aristotelian and Platonic philosophy, Plotinus metaphorically identified the demiurge (or nous) within the pantheon of Greek gods as Zeus.

Henology

Plotinus describes the first and highest aspect of God as the One (Τὸ Ἕν), the source or the Monad. This is the God above the demiurge and manifests through the actions of the demiurge. The Monad emanated the demiurge or Nous (consciousness) from his vitality & # 34;indeterminate & # 34; because the monad was so abundant that it overflowed on itself, causing self-reflection. Plotinus referred to this self-reflection of indeterminate vitality as the "demiurge" or creator. The second principle is the organization in its reflection of the non-sensible force or dynamis, also called the one or the Monad. The dyad is energeia emanated by the one that is then the work, process or activity called nous, demiurge, mind, consciousness that organizes the indeterminate vitality in the experience called the material world, universe, cosmos. Plotinus also clarifies the equation of matter with nothing or non-being in The Enneads, which more correctly refers to expressing the concept of idealism or that there is nothing and nowhere outside of the "mind" or the nous (cf. pantheism).

Plotinus's form of Platonic idealism is to treat the demiurge, nous as the contemplative faculty (ergon) within man that commands force (dynamis) in conscious reality. In this, he claimed to reveal Plato's true meaning: a doctrine he learned from the Platonic tradition and which did not appear outside of academia or in Plato's text. This tradition of the creator God as nous (the manifestation of consciousness), can be validated in the works of philosophers prior to Plotinus such as Numenius, as well as a connection between Hebrew and Platonic cosmology (see also Philo)..

The Demiurge of Platonism is the Nous (mind of God), and it is one of the three ordering principles:

- Arché (gr. 'comienzo') - the source of all things,

- Logos (gr. 'reason', 'cause') - the underlying order hidden under appearances,

- Harmonia (gr. 'armony') - numerical proportions in mathematics.

Before Numenius of Apamea and Plotinus' Enneads, no Platonic work clarified ontologically the demiurge of Plato's Timaeus allegory. However, the idea of the demiurge was addressed before Plotinus in the works of the Christian writer Justin Martyr, who built his understanding of the demiurge on the works of Numenius.

Iamblichus

Later, the Neoplatonist Jamblichus changed the role of the One, effectively altering the role of the demiurge as a second cause or dyad, one of the reasons why Jamblichus and his teacher Porphyry came into conflict.

The figure of the demiurge arises in the theory of Iamblichus, who conjugates the transcendent, incommunicable One or Source. Here, at the top of this system, the Source and the Demiurge (material realm) coexist through the process of henosis. Jamblichus describes the One as a monad whose first principle or emanation is intellect (nous), while among "the many" Following it is a second superexistent One which is the producer of intellect or soul (psyche).

The One is further divided into spheres of intelligence: the first and superior sphere is that of the objects of thought, while the last sphere is the domain of thought. Thus, a triad of intelligible nous, intellective nous and psyche is formed to further reconcile the various Hellenistic philosophical schools of actus and potentia (actuality and potentiality) of Aristotle of the immobile motor and the demiurge of Plato. Then, within this intellectual triad, Iamblichus assigns the third rank to the demiurge, identifying him with the perfect or divine nous with the intellectual triad being promoted to a hebdomad (pure intellect).. In Plotinus's theory, the nous produces nature through intellectual mediation, so the intellectualizing gods are followed by a triad of psychic gods.

Mythology

The demiurge is a computer genius. In the beginning there was a chaotic, disorderly, shapeless, indeterminate mass, etc., and there was also the demiurge, who looked at this mass and thought: «what can I do with it? I don't know what I'm going to do, but whatever I do, I'm going to do it well." Then he devised one by one the things that he was going to do and according to his idea he did them.

The myth of the demiurge implies the following:

- The idea of good is the first of all ideas.

- Ideas are prior to things and are cause of them.

- Ideas are the only truth.

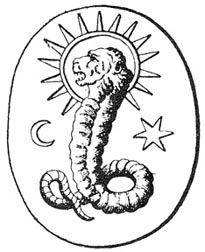

Gnosticism

The Platonic concept of the demiurge is taken up by Gnosticism. What in Platonism was imperfection, in Gnosticism it becomes evil. The Universe was for the Gnostics a gradation, from the most subtle (God) to the lowest (matter). Thus the demiurge as creator and organizer of the material world, becomes the incarnation of evil, imprisoning men and chaining them to material passions.

The spirit is the only part of divinity that corresponds to the human being, waging a "battle" permanent in front of the body and the material, thus transforming the earth into hell, understanding by hell not the concept of Hades or the underworld, but simply the place furthest away from God. Only sophia, wisdom, gnosis, comes out of love, from the subtle to the earth to free the human being from the slavery of matter. Salvation is not a matter of belief or divine mercy, but becomes a revelation, only possible for those who have not yet completely lost the little bit of divinity that all human beings possess.

Philosophy and literature

- With Friedrich Hegel, the process of thinking becomes demiurgo, to which it transforms into independent and divinized force. Demiurgo is the creative force, the supreme intelligence.

- The Romanian philosopher Émile Cioran wrote a book in which he deals in large from a nihilistic point of view: The aciago demiurgo (1969).

- Gustav Meyrink, among others, The Golemin its introduction to texts attributed to Saint Thomas Aquinas (Treaty of the Philosopheric Stone and Alchemy Treaty) quotes a phrase that attributes to Buddha Gautama:

Looking for the builder of the building, I have walked without pause the circular journey of many lives. Now I have found you and I have penetrated your being. You'll never build me any house again!Gustav Meyrink.

- According to the essayist Burkhardt Gorissen, the demiurgo and the Great Architect of the Universe of Freemasonry are the same entity.

- Jorge Luis Borges mentions in the library of Babel the "meterial demiurgos" as the hypothetical creators of the people who inhabit and travel through the infinite galleries.

Contenido relacionado

Abbey

Macedonianism

Religion in Panama