Declaration of Independence of the United States of America

The Declaration of Independence of the United States of America (whose official title is The unanimous declaration of the thirteen United States of America) is a document drafted by the second Continental Congress—in the Pennsylvania State House (now Independence Hall).) in Philadelphia on July 4, 1776—which proclaimed that the Thirteen American Colonies—then at war with the Kingdom of Great Britain—had defined themselves as thirteen new sovereign and independent states and no longer recognized British rule;instead, they formed a new nation: the United States. John Adams was one of the politicians who undertook the independence process, approved on July 2 by the full Congress without opposition. A committee (the Committee of Five) was charged with drafting the formal declaration, which was presented when Congress voted on it two days later.

Adams persuaded the committee to give Thomas Jefferson the task of directing the writing of the original draft of the document, which Congress edited to produce the final version. The Declaration was essentially a formal explanation of why Congress broke political ties with Britain on July 2, more than a year after the outbreak of the American Revolution. The next day, Adams wrote to his wife Abigail: "The second day of July, 1776, will be the most memorable time in the history of America." However, Independence Day is celebrated two days later, on which date It was approved.

On July 4—after ratifying the text—Congress released the Declaration in various forms. It was initially published in John Dunlap's flyer, which was widely distributed and read to the public. The original copy used for this printing has been lost and may have been in the possession of Jefferson. The original draft with corrections by Adams and Benjamin Franklin and additional notes by Jefferson on the changes made by Congress are preserved in the Library of the Congress. The best-known version of the Declaration—a signed copy that is popularly regarded as the official document—is on display at the National Archives in Washington, D.C. This handwritten copy was requested by Congress on July 19 and signed on August 2.

The content and interpretation of the Declaration have been the subject of much academic research. For example, the document justified the independence of the United States by listing colonial claims against King George III and asserting certain natural and legal rights, including the right of revolution. Having fulfilled its original mission of announcing independence, references to the text of the Declaration were few in the following years. Abraham Lincoln made it the centerpiece of his rhetoric (as in the 1863 Gettysburg Address) and his policies. Since then, it has become a well-known claim on human rights, in particular his second sentence:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

The latter has been called "one of the best-known phrases in the English language" and containing "the most powerful and consistent words in American history". The passage came to represent a moral model that the United States should strive for. to fulfill and such a view was notably promoted by Lincoln, who considered the Declaration to be the foundation of his political philosophy and held that it was a proclamation of principles through which the Constitution of the United States should be interpreted.

The United States Declaration of Independence inspired many other similar documents in other countries, and its ideas gained adherence in the Netherlands, the Caribbean, Spanish America, the Balkans, West Africa, and Central Europe in the years before 1848. Great Britain did not it recognized the independence of its former colonies until the war reached a stalemate. The 1783 Treaty of Paris ended hostilities and consummated the American Revolution.

Historical context

| Believe me, dear Sir: there is not in the British empire a man who more cordially loves a union with Great Britain than I do. But, by the God that made me, I will cease to exist before I yield to a connection on such terms as the British Parliament propose; and in this, I think I speak the sentiments of America.Translation [show]—Thomas Jefferson (November 29, 1775). |

Before the Emancipation Act was passed in July 1776, the Thirteen Colonies and the Kingdom of Great Britain had been at war for more than a year. Relations between the two had deteriorated since 1763. The British Parliament enacted a series of measures to increase taxes in the colonies, such as the Stamp Act of 1765 and the Townshend Acts of 1767. This legislative body considered that these regulations were a legitimate means for the colonies to pay a fair share of the costs of keeping them in the British Empire.

However, many colonists had developed a different concept of empire. The colonies were not directly represented in Parliament and the colonists argued that this legislature had no right to tax them. This tax dispute was part of a larger divergence between British and American interpretations of the British Constitution and the scope of the authority of Parliament in the colonies. The orthodox view of the British—dating from the Glorious Revolution of 1688—held that Parliament had supreme authority throughout the empire and, by extension, everything Parliament did it was constitutional.However, the idea had developed in the colonies that the British Constitution recognized certain fundamental rights that could not be violated by the government, not even by Parliament. After the Townshend Acts, some essayists even began to question whether Parliament had any legitimate jurisdiction in the colonies. Anticipating the creation of the Commonwealth of Nations, in 1774 American literati—including Samuel Adams, James Wilson, and Thomas Jefferson—discussed whether Parliament's authority was limited to Great Britain alone and that the colonies, which had their own legislatures, were to relate to the rest of the empire solely out of loyalty to the Crown.

Convocation of the Congress

The issue of Parliament's authority in the colonies became a political crisis after in 1774 that legislature passed Coercive Acts (known as Intolerable Acts in the colonies) to punish the Massachusetts Bay Province for mutiny. of tea in Boston the previous year. Many colonists considered the coercive laws to be a violation of the British Constitution and thus a threat to the liberties of all of British America. In September 1774, the first Continental Congress met in Philadelphia to coordinate a response.At that assembly a boycott of British goods was organized and he petitioned the king for the annulment of the laws. These measures failed because King George III and Prime Minister Frederick North's government were determined not to compromise on parliamentary supremacy. In fact, in November 1774 the monarch wrote to North saying " blows must decide whether they are to be subject to this country or independent ".

Most colonists hoped for a reconciliation with the mother country, even after the Revolutionary War began in Lexington and Concord in April 1775. The Second Continental Congress met in the Pennsylvania State House in Philadelphia in May 1775 and some representatives expected the consequent independence, but there was no discussion in declaring it.Although many colonists no longer believed that Parliament had sovereignty over them, they still professed loyalty to George III and hoped that he would intercede on their behalf. In late 1775 they were disillusioned when the King refused Congress's second request, issued a proclamation of rebellion, and announced to Parliament on 26 October that he was considering "friendly offers of foreign aid" to suppress the uprising. A pro-American minority in Parliament he warned that the central government was encouraging the settlers to independence.

Towards independence

A pamphlet by Thomas Paine, Common Sense , was published in January 1776, at the same time that it was clear in the colonies that the king was unwilling to act as a conciliator. Paine had settled in the colonies and advocated colonial independence, republicanism as an alternative to the monarchy and its hereditary system. Common sense introduced no new ideas and probably had little direct effect on Congress and its reasons for independence; its importance lies in the fact that it stimulated public debate on a subject that few had dared to speak openly about.Support for emancipation increased steadily after the publication of Paine's pamphlet.

Hopes for reconciliation began to wane among the colonists, for by early 1776 public support for independence had strengthened. In February of that year they learned of the passage of the Prohibitive Act in Parliament which established the blockade of American ports and declared that colonial ships were enemy ships. John Adams—a strong supporter of independence—believed that Parliament he had effectively declared independence before Congress had done anything and designated the Prohibition Act as the "Independence Act", calling it "a complete Dismemberment of the British Empire ".Support for declaring independence grew further when it was confirmed that King George III had hired German mercenaries (some 30,000 over the course of the war) to attack his American subjects.

Despite this growing popular support for independence, Congress lacked the authority to declare it. Representatives were elected to Congress by thirteen different governments—including illegal conventions, ad hoc committees, and democratic assemblies—and were bound to perform only the duties assigned to them. Regardless of their personal views, representatives could not vote to declare independence unless their instructions permitted such action. Indeed, some colonies expressly prohibited their representatives from taking action to secede from Britain, while others gave them vague orders. about the topic.As public opinion favorable to emancipation grew, independence advocates sought revision of the representatives' orders. In order for Congress to declare independence, a majority of delegations would need authorization to vote in favor of independence. that matter, and at least one colonial government would have to specifically instruct (or give permission) its delegation to propose a declaration of independence in Congress. Between April and July 1776, a "complex political war" was waged to achieve that goal.

Review of instructions

In the midst of the campaign to review the orders of representatives to Congress, many settlers formally expressed their support for separation in several simultaneous declarations of independence at the state and local levels. Historian Pauline Maier identified more than ninety such proclamations issued in the Thirteen Colonies from April to July 1776. These "declarations" had significant differences. Some were formal written instructions for delegations to Congress, such as the Halifax resolutions of April 12 in which North Carolina became the first colony to explicitly authorize its representatives to vote for independence.Others were legislative acts that officially broke with British rule, such as the Rhode Island legislature declaring independence on May 4 (the first colony to do so). The rest were resolutions passed at town hall meetings and county meetings that they offered support for independence; a few appeared in the form of court orders, such as the published statement of William Henry Drayton, Chief Justice of South Carolina: "The law of the earth authorizes me to declare... that George III, King of Great Britain...,] has no authority over us and we owe him no obedience” (the law of the land authorizes me to declare... that George the Third, King ofGreat Britain ... has no authority over us, and we owe no obedience to him). Most of these proclamations are little known and have been overshadowed by the Declaration passed in the Continental Congress on July 2 and signed on July July.

Some colonies refused to support independence. The resistance focused on the colonies of New York, New Jersey, Maryland, Pennsylvania and Delaware. The defenders of independence focused their efforts on Pennsylvania, because if that colony turned to the pro-independence cause then the others would follow. However, on May 1 opponents retained control of the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly in a special election that focused on the question of independence. In response, on May 10 John Adams and Richard Henry Lee introduced a draft resolution in Congress requiring colonies without a "government adequate to [meet] the exigencies of their affairs" to elect new governments.The motion passed unanimously and was even supported by John Dickinson, leader of the Pennsylvania anti-independence faction in Congress, who believed that it did not apply to his colony.

May 15 Preamble

| This Day the Congress has passed the most important Resolution, that ever was taken in AmericaTranslation [show]—John Adams (May 15, 1776). |

As was customary, Congress appointed a committee to draft a preamble that would explain the purpose of the resolution. Mainly composed by Adams, the text stated that, because King George III rejected reconciliation and was hiring foreign mercenaries to break into the colonies, "it is necessary that the exercise of any kind of authority under that Crown be completely suppressed". Adams.'sCongress approved the bill on May 15 after several days of deliberation, but four of the colonies voted against it, and the Maryland delegation left the room in protest. Adams considered its preamble to be effectively a declaration of independence., although it still had to be presented as a formal document.

Lee's Resolution

On the same day that Congress passed Adams's preamble, the Virginia Convention laid the groundwork for an official declaration of independence in Congress. On May 15, the convention instructed its delegation to Congress "to propose to that respected body to declare the United Colonies free and independent States, freed from any allegiance to or dependence on the Crown or Parliament of Great Britain. " In accordance with those orders, Richard Henry Lee introduced a three-part resolution in Congress on June 7. The motion was seconded by John Adams and he even invited Congress to declare independence that same day, form foreign alliances and prepare a plan. of colonial confederation.The part of the resolution relating to emancipation reads:

Resolved, that these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.Resolved, That these United Colonies are, and by right must be, free and independent States, free from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and must be, totally dissolved.

Lee's resolution met resistance in the ensuing debate. Opponents admitted that reconciliation with Britain was unlikely, but while declaring independence premature and obtaining foreign assistance should take precedence. Proponents argued that foreign governments would not intervene in an internal dispute over British territory, so a formal proclamation of independence was necessary before that option was possible. They insisted that all the Continental Congress had to do was "declare a fact which already exists ".However, representatives from Pennsylvania, Delaware, New Jersey, Maryland, and New York were still not allowed to vote for independence, and some threatened to leave Congress if the resolution passed. Therefore, on June 10, Congress decided to postpone deliberation of the Lee resolution for three weeks. Until then, Congress determined that a committee should prepare a document announcing and explaining independence in the event that Lee's resolution Lee was approved when it was discussed again in July.

Latest authorizations

Support for a declaration of independence from Congress solidified in the last weeks of June 1776. On June 14, the Connecticut Assembly instructed its delegates to propose independence, and the next day, the New Hampshire and Delaware legislatures they also authorized their representatives. In Pennsylvania, political disputes ended with the dissolution of the colonial parliament and the creation of the Conference of Committees—led by Thomas McKean—which on June 18 authorized Pennsylvania delegates to declare independence. On June 15, the Provincial Congress of New Jersey—ruling provisionally since January 1776—decided that Colonial Governor William Franklin was "an enemy of the liberties of this country" (an enemy to the liberties of this country) and ordered his arrest. On June 21, they elected new delegates to Congress and accredited them to support a proclamation of independence.

By the end of June, Maryland and New York were still not clearing their delegates. Previously, representatives from Maryland had withdrawn when the Continental Congress approved Adams's preamble on May 15 and petitioned the Annapolis Convention for new orders. On May 20, that assembly rejected Adams's preamble and dictated to its delegates oppose independence. However, Representative Samuel Chase returned to Annapolis and, by showing them the local resolutions in favor of independence, managed to change their minds on June 28.Only the New York delegates were unable to receive further instructions. On June 8, when the Continental Congress was considering the independence resolution, the president of the New York Provincial Congress told the representatives to wait, but on June 30 this assembly ordered the evacuation of New York when troops The British approached and did not meet again until July 10. This meant that delegates from New York would not be authorized to declare independence until Congress allowed it.

Drafting and approval

While the aforementioned political maneuvers that consolidated the independence process in the state legislatures were taking place, a document was being drafted that would explain the decision. On June 11, 1776, Congress appointed a "Committee of Five" for that task, composed of by John Adams (Massachusetts), Benjamin Franklin (Pennsylvania), Thomas Jefferson (Virginia), Robert R. Livingston (New York), and Roger Sherman (Connecticut). The committee did not leave meeting minutes, so there is some uncertainty about How did the writing process unfold? Years later, some documents of Jefferson and Adams explained part of the meetings, although they are not reliable they are frequently cited in the bibliography.The truth is that the committee discussed the general outline that the document should follow and agreed that Jefferson would write the first draft. The members of the committee in general and Jefferson in particular, thought that Adams should write the document, but the latter convinced the committee to elect Jefferson and promised to review it personally. Considering Congress's busy schedule, Jefferson probably had little time to write for the next seventeen days and also had to write the draft quickly. He then consulted with his peers, made some changes and produced another draft incorporating those corrections.The committee presented this copy to Congress on June 28, 1776. The title of the document was "A Declaration of the Representatives of the United States of America, Assembled in General Congress.

The president of Congress ordered that the draft "rest on the table" (lie on the table or postpone or suspend its consideration in plenary). Over two days, Congress methodically edited Jefferson's main document, removing a quarter of the text, removing unnecessary words, and improving sentence structure. Congress withdrew Jefferson's claim that Britain had forced the trade of African slaves in the colonies, in order to moderate the document and appease British supporters of the Revolution. Jefferson wrote that Congress had "mangled ") his preliminary version, but, in the words of his biographer John Ferling, the final product was "the majestic document that inspired contemporaries and posterity".

On Monday, July 1, after submitting the draft declaration, Congress reverted to a committee of the whole—chaired by Benjamin Harrison (Virginia)—and resumed debate on Lee's independence resolution. John Dickinson made a last-ditch effort to delay the decision, on the grounds that Congress should not declare independence without first securing a foreign alliance and finalizing the Articles of Confederation. John Adams gave a speech in response to Dickinson, in which he reaffirmed the need for an immediate statement.

The vote came after a long day of speeches. Each colony was entitled to cast one vote, but—because each delegation had between two and seven members—they had to vote among themselves to determine the decision of the represented colony. Pennsylvania and South Carolina voted against. The New York delegation abstained, not having permission to vote for independence. Delaware did not vote because the delegation was split between Thomas McKean (who voted yes) and George Read (who voted no). The remaining nine delegations voted in favor of independence, which meant that the resolution had been approved by the committee of the whole.The next step was for the resolution to be put to a vote by Congress itself. Edward Rutledge (South Carolina) opposed Lee's resolution, but — "eager for consensus" from his colleagues — proposed that the vote be postponed until the next day.

On July 2, South Carolina reversed its position and voted for independence. In the Pennsylvania delegation, Dickinson and Robert Morris abstained and allowed the delegation to decide (three to two) to support independence. The tie in the Delaware delegation was broken by the arrival of Caesar Rodney, who voted for independence. The New York delegation abstained once again, as it was not yet authorized to vote for independence (the New York Provincial Congress allowed them a week later). The proclamation of independence passed with twelve affirmative votes and one vote. abstention at 6:26 p.m. (local time). With this, the colonies officially severed their political ties with Great Britain.The following day, John Adams wrote in a letter to his wife Abigail, stating that July 2 would become a great national holiday because he thought the vote for independence would be commemorated. He did not consider that Americans—including himself—would celebrate Independence Day on the date the Committee of Five text was announced as approved.

I am apt to believe that [Independence Day] will be celebrated, by succeeding Generations, as the great anniversary Festival. It ought to be commemorated, as the Day of Deliverance by solemn Acts of Devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more.I believe that [Independence Day] will be celebrated, for future generations, as the great anniversary festival. It should be commemorated, like the day of liberation, by solemn acts of devotion to Almighty God. It should be solemnized with pomp and parade, with shows, games, sports, cannon fire, bells, bonfires, and illuminations from one end of this continent to the other forever.John Adams to his wife Abigail, July 3, 1776.

After the vote on the independence resolution, Congress turned its attention to the Committee of Five's draft. Over the next two days, Congress made some redrafting and deleted nearly a quarter of the text, and on the morning of July 4, 1776, the text of the Declaration of Independence was approved and sent to the printer. for publication.

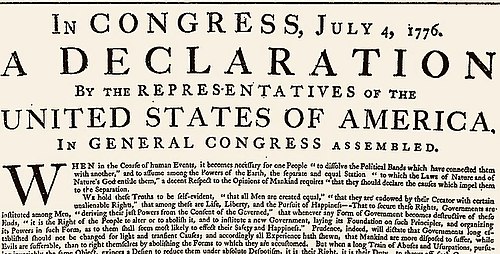

Introduction to the original Declaration document, printed July 4, 1776 under Jefferson's supervision. The manuscript copy was printed later (as seen in the card at the beginning of this article). Note that the fonts of the introduction differ between the two versions.

Introduction to the original Declaration document, printed July 4, 1776 under Jefferson's supervision. The manuscript copy was printed later (as seen in the card at the beginning of this article). Note that the fonts of the introduction differ between the two versions.

There is a difference in the wording of the original printing of the Declaration with the final official, handwritten copy. The word "unanimous" was inserted after a resolution of Congress passed on July 19, 1776:

Resolved, That the Declaration passed on the 4th, be fairly engrossed on parchment, with the title and stile of "The unanimous declaration of the thirteen United States of America," and that the same, when engrossed, be signed by every member of Congress.We resolve, That the Declaration approved on the 4th, be precisely the handwritten version on parchment, with the title and design of «The unanimous declaration of the thirteen United States of America», and that the same, when handwritten, be signed by each member of Congress.

Content of the manuscript version of the Declaration

The Declaration is not divided into formal sections, but is discussed in the bibliography in a five-part division: introduction, preamble, indictment of King George III, denunciation of the British people, and conclusion.

| Introduction It affirms that a matter of Natural Law allows a people to assume its political independence; recognizes that the reasons for such independence must be reasonable and, therefore, explainable and must be expressed. | In CONGRESS, July 4, 1776. The unanimous declaration of the thirteen United States of America,When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.Translation [show] |

| Preamble Describes a general governmental philosophy that justifies revolution when the government harms natural rights. | We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.Translation [show] |

| Accusation A charter documenting the king's "repeated grievances and usurpations" against the rights and freedoms of the colonists. | Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world.He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good.He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing importance, unless suspended in their operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them.He has refused to pass other Laws for the accommodation of large districts of people, unless those people would relinquish the right of Representation in the Legislature, a right inestimable to them and formidable to tyrants only.He has called together legislative bodies at places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the depository of their Public Records, for the sole purpose of fatiguing them into compliance with his measures.He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly firmness of his invasions on the rights of the people.He has refused for a long time, after such dissolutions, to cause others to be elected, whereby the Legislative Powers, incapable of Annihilation, have returned to the People at large for their exercise; the State remaining in the mean time exposed to all the dangers of invasion from without, and convulsions within.He has endeavoured to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither, and raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands.He has obstructed the Administration of Justice by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary Powers.He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries.He has erected a multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harass our people and eat out their substance.He has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures.He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil Power.He has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution, and unacknowledged by our laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation:For quartering large bodies of armed troops among us:For protecting them, by a mock Trial from punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States:For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world:For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent:For depriving us in many cases, of the benefit of Trial by Jury:For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offences:For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government, and enlarging its Boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these ColoniesFor taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments:For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with power to legislate for us in all cases whatsoever.He has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us.He has plundered our seas, ravaged our coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people.He is at this time transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the works of death, desolation, and tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty & Perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized nation.He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high Seas to bear Arms against their Country, to become the executioners of their friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands.He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. A Prince, whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people.Translation [show] |

| Complaint Essentially this section concludes the cause of independence. The conditions that justified the revolution are demonstrated. | Nor have We been wanting in attentions to our British brethren. We have warned them from time to time of attempts by their legislature to extend an unwarrantable jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the circumstances of our emigration and settlement here. We have appealed to their native justice and magnanimity, and we have conjured them by the ties of our common kindred to disavow these usurpations, which, would inevitably interrupt our connections and correspondence. They too have been deaf to the voice of justice and of consanguinity. We must, therefore, acquiesce in the necessity, which denounces our Separation, and hold them, as we hold the rest of mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace Friends.Translation [show] |

| conclusion The signatories indicate that there are conditions under which the people must change their government, that the British have produced such conditions and, of necessity, the colonies must cast off political ties to the British Crown and become independent states. Essentially, the conclusion contains Lee's resolution that had been passed on July 2. | We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these united Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States; that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.Translation [show] |

| Signatories The first and most famous signature on the manuscript copy was that of John Hancock, President of the Continental Congress. Two future Union presidents (Thomas Jefferson and John Adams) and a father and great-grandfather of two other presidents (Benjamin Harrison) were among the signers. Edward Rutledge (26 years old) was the youngest signatory and Benjamin Franklin (70 years old) was the oldest. The fifty-six signers of the Declaration represented new states, as listed (from north to south): | New Hampshire: Josiah Bartlett, William Whipple, Matthew ThorntonMassachusetts: Samuel Adams, John Adams, John Hancock, Robert Treat Paine, Elbridge GerryRhode Island: Stephen Hopkins, William ElleryConnecticut: Roger Sherman, Samuel Huntington, William Williams, Oliver WolcottNew York: William Floyd, Philip Livingston, Francis Lewis, Lewis MorrisNew Jersey: Richard Stockton, John Witherspoon, Francis Hopkinson, John Hart, Abraham ClarkPennsylvania: Robert Morris, Benjamin Rush, Benjamin Franklin, John Morton, George Clymer, James Smith, George Taylor, James Wilson, George RossDelaware: George Read, Caesar Rodney, Thomas McKeanMaryland: Samuel Chase, William Paca, Thomas Stone, Charles Carroll of CarrolltonVirginia: George Wythe, Richard Henry Lee, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Harrison, Thomas Nelson, Jr., Francis Lightfoot Lee, Carter BraxtonNorth Carolina: William Hooper, Joseph Hewes, John PennSouth Carolina: Edward Rutledge, Thomas Heyward, Jr., Thomas Lynch, Jr., Arthur MiddletonGeorgia: Button Gwinnett, Lyman Hall, George Walton |

Philosophical origins and legal situation

Historians have attempted to identify the sources that most influenced the content and political philosophy of the proclamation. According to the Jefferson papers, the Declaration contained no original ideas, but rather a statement of sentiment shared by supporters of the American Revolution. As he explained in a missive dated May 8, 1825:

Neither aiming at originality of principle or sentiment, nor yet copied from any particular and previous writing, it was intended to be an expression of the American mind, and to give to that expression the proper tone and spirit called for by the occasion.Neither claimed originality of principle or sentiment, nor copied from any particular [or] previous writing, [but] aspired [to be] an expression of the American mind, and to give that expression the tone and spirit required by the occasion.

Jefferson's most immediate references were two documents written in June 1776: his draft of the preamble to the Virginia Constitution and George Mason's draft Virginia Declaration of Rights. The ideas and phrases of both appear in the Emancipation Act. In turn, they were directly influenced by the English Bill of Rights of 1689, which formally overthrew the reign of King James II. During the revolution, Jefferson and other colonists took inspiration from the English Bill of Rights as a model for "ending the tyranny of an unjust king."The Declaration of Arbroath (1320) and the Act of Abjuration (1581) were also proposed as models for the Declaration of Jefferson, but few scholars now acknowledge such influence.

Jefferson mentioned that several authors exerted a general influence on the content of the Declaration. The English political theorist John Locke is cited by historians as one of the primary influences, he was even described by Jefferson as one "of the three greatest men who have ever lived." In 1922, historian Carl Lotus Becker noted that "most Americans had absorbed Locke's works as a kind of political gospel; and the Declaration, in its form, in its phraseology, closely follows certain phrases in Locke's second treatise on government.Locke developed the idea of the equality of human beings from the biblical story of creation, more precisely in Genesis 1:26-28 (which exegetes point to as the origin of the theological doctrine that the human being was created to likeness of God). From this foundation of equality, originated the concept of liberty, the participatory rights of the individual, and the principle that a government should exercise power only with the consent of the governed. This is the deduction central to the Declaration, since it establishes the right of colonists to break with the British monarchy and take their political life into their own hands.According to Middlekauff, much of the Revolutionary War generation was convinced that nature, the entire universe, was "created by God" through his divine providence. This notion by Protestant Christians—mainly George Washington—determined that independence arose from "the hands of Providence" and, in this way, was a "glorious cause" for the benefit not only of the colonies, but of all humanity.

However, some later scholars have questioned Locke's influence on the American Revolution. In 1937, historian Ray Forrest Harvey affirmed the pervasive influence of Swiss jurist Jean-Jacques Burlamaqui and argued that Jefferson and Locke were at "two opposite poles" in their political philosophy; Harvey demonstrated this in the Declaration with Jefferson's phrase "pursuit of happiness" instead of "property , " which Locke had spelled out as "life, liberty, and patrimony . " and estate) of a person. This does not mean that Jefferson believed that the pursuit of happinessit referred primarily or exclusively to property; under this assumption, the spirit of the Declaration expresses that the republican government exists for the reasons that Locke idealized and that line of thought has been extended by some academics to support a conception of limited government. Other scholars highlighted the influence of the Republicanism rather than Locke's classical liberalism. Historian Garry Wills considered that Jefferson's reasoning was influenced by the Scottish Enlightenment—particularly Francis Hutcheson—and not by Locke, but this interpretation has been strongly criticized.

Legal historian John Phillip Reid pointed out that the emphasis on political philosophy has been lost and that what is being spoken of is not a philosophical treatise on natural rights, but a legal document—an indictment against King George III for violating constitutional rights. of the settlers). Historian David Armitage argued that the Declaration was greatly influenced by Emer de Vattel's The Law of Nations (Le droit des gens)—the dominant international law treatise at the time; as Benjamin Franklin testified, this book "was continually in the hands of the members of our Congress."Armitage adds: "[For] Vattel, independence was central to his definition of the state"; thus, the primary purpose of the Declaration was "to express the international legal sovereignty of the United States." If the Union had any hope of being recognized by the European powers, the revolutionaries had to make it clear that they were no longer dependent on Britain.According to historian George Billias: "Independence amounted to a new state of interdependence: the United States was now a sovereign nation entitled to the privileges and responsibilities that came with that status. The United States thus became a member of the international community, which meant becoming an artisan of treaties and alliances, a military ally in diplomacy, and a partner in foreign trade on a more equitable basis.

Currently, the Emancipation Act does not have the force of law at the national level, but it can help provide historical and legal clarity on the Constitution and other laws.

Signatories

The proclamation became official when Congress voted on it on July 4, and delegate signatures were not required for it to go into effect. The handwritten copy of the Declaration signed by Congress is dated July 4, 1776. At the bottom of the scroll are the names of fifty-six representatives; however, the exact date each person signed it has long been the subject of debate. For example, Jefferson, Franklin, and Adams wrote that the Declaration had been signed by Congress on July 4, but, in 1796, one of the signatories—Thomas McKean—indicated that the signing of the document was on July 4, and some signatories were not present or even authorized by Congress until after that date.

The Declaration was transcribed onto separate paper, approved by the Continental Congress, and signed by John Hancock, President of Congress, on July 4, 1776, according to the 1911 U.S. State Department record under Secretary Philander Chase. Knox. On August 2, 1776, a vellum copy of the Declaration was signed by 56 people, although many of these signatories were not present when the original Declaration was approved on July 4. Signer Matthew Thornton (New Hampshire) was authorized to the Continental Congress in November; he requested the privilege of adding his signature at that time and signed on November 4, 1776.

Historians generally accept McKean's version of events, considering the famous version of the Declaration to have been printed after July 19 and not signed by Congress until August 2, 1776. In 1986, the Legal historian Wilfred Ritz argued that scholars had misread the primary sources and gave McKean too much credibility, since he was not present at Congress on July 4. According to Ritz, some 34 delegates signed the Declaration on July 4 and the rest on or after August 2. Historians who reject the July 4 hypothesis maintain that most representatives signed on August 2 and that those who were not present they added their names later.

Two future presidents of the United States were among the signatories: Thomas Jefferson and John Adams. The most famous signature on the manuscript copy is that of John Hancock, who supposedly put his name first because he was the president of Congress. Hancock's large, conspicuous signature became iconic, and in the United States his name became a synonym. of "signature" since 1903, according to the Merriam-Webster dictionary. An anecdote states that after Hancock signed, he commented: "The British ministry can read that name without glasses" (The British ministry can read that name without spectacles). Another indicates that Hancock proudly declared, “Whoa! I suppose King George will be able to read this!” (There! I guess King George will be able to read that!').

Years later, various legends arose about the signing of the Declaration, when the document had become an important national symbol. In a famous story, John Hancock reportedly said that members of Congress—after they had signed the Declaration—should " all hang together," and Benjamin Franklin replied, "Yeah, we have to stay together or surely we [they're going] to hang separately» (Yes, we must indeed all hang together, or most assuredly we shall all hang separately). However, the quote did not appear in print until more than fifty years after Franklin's death.

The Syng inkwell used in the firm was also used in the approval of the Federal Constitution in 1787.

Post and Reactions

After Congress approved the final text of the Declaration on July 4, a handwritten copy was sent to John Dunlap's printing press, located a few blocks away. Overnight, Dunlap printed some 200 flyers for distribution. Before long, the Declaration was read to the public and reprinted in newspapers in all thirteen states. The first official recitation of the document was by John Nixon in the courtyard of Independence Hall on July 8; other public readings also occurred that day in Trenton and Easton. A German translation was published in Philadelphia on July 9.

The President of the Congress, John Hancock, sent a leaflet to General George Washington, instructing him to proclaim her "as the Head of the Army in the way you think most appropriate" (at the Head of the Army in the way you shall think it most proper). Washington read the Declaration to its troops on July 9 in New York City, while thousands of British soldiers were on ships near the harbor. Washington and Congress hoped the Declaration would inspire the military and encourage others to join.After listening, inhabitants in many cities tore down and destroyed signs or statues that represented royal authority. An equestrian statue of King George III in New York was toppled and its lead remelted to make musket balls.

British officials in North America sent copies of the proclamation to Britain; the text was published in British newspapers in mid-August, it reached Florence and Warsaw in mid-September, and a German translation appeared in Switzerland in October. The first copy sent to France was lost en route, and the second arrived in November 1776.

The colonial authorities in Latin America prohibited the circulation of the Declaration, but this did not prevent its dissemination and translation by the Venezuelan Manuel García de Sena, the Colombian Miguel de Pombo, the Ecuadorian Vicente Rocafuerte and the Americans Richard Cleveland and William Shaler, who distributed the Declaration and the Constitution of the United States between the Creoles of Chile and the Indians in Mexico in 1821. The British Northern Ministry did not give an official response to the Declaration, but instead secretly commissioned John Lind to publish a pamphlet entitled Response to the Declaration of the American Congress (Answer to the Declaration of the American Congress ).English (Conservatives) charged that the Declaration's signatories did not apply the same principles of "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness" to African Americans. Thomas Hutchinson—former colonial governor of Massachusetts—also published a rebuttal questioning several of the Declaration. He asserted that the American Revolution was the work of " there were men in each of the principal Colonies " who "had no other claim than to demand independence" (they could have no other pretense to a claim of independence) and that they finally achieved it by inducing the “good and loyal subjects” (good and loyal subjects) to rebel.Lind's pamphlet was an anonymous attack on the concept of natural rights idealized by Jeremy Bentham; this situation was also repeated in the French Revolution. Lind and Hutchinson's pamphlets questioned why American slaveholders in Congress proclaimed that "all men are created equal" without freeing their slaves.

William Whipple—a Declaration signer who had fought in the war—freed his slave Prince Whipple because of his revolutionary ideals. In the postwar decades, other slaveholders also freed their slaves. From 1790 to 1810, the percentage of free blacks in the Upper South increased from about 1% to 8.3%. By 1804 the northern states had passed legislation that they gradually abolished slavery.

Destination of the copies

The official copy was the one printed on July 4, 1776 under Jefferson's supervision. It was sent to the states and the military and reprinted in major newspapers. The slightly different "handwritten copy" (shown at the beginning of this article) was later made to be signed by members. This version is the most widely distributed in the 21st century. Note that the lines of the introduction differ between the two versions.

The copy of the Declaration that was signed by Congress is known as the parchment or manuscript copy. It was probably handwritten very carefully by clerk Timothy Matlack. An 1823 facsimile has become the standard for most modern reproductions, due to poor preservation of the original from the 19th century. In 1921, custody of the manuscript copy was transferred from the State Department to the Library of Congress, along with the United States Constitution. After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the documents were moved to the fortified vault at Fort Knox, Kentucky, where they remained until 1944.In 1952, the manuscript version was again transferred to the National Archives and is now on permanent display in the National Archives' Rotunda for the Charters of Freedom.

The document signed by Congress and displayed in the National Archives is often considered the only Declaration of Independence, but historian Julian P. Boyd pointed out that the Declaration of Independence—like the Magna Carta—is not a single document and considered that the fliers printed by order of Congress were also official texts. The Declaration was first published in flier format on the night of July 4 by John Dunlap in Philadelphia. Dunlap printed about 200 fliers, of which 26 they have survived. The 26th copy was discovered in the British National Archives in 2009.

In 1777, Congress commissioned Mary Katherine Goddard to print a new pamphlet listing the signers of the Declaration, unlike Dunlap's work. Nine copies of Goddard's pamphlet and other state-printed pamphlets. still

Likewise, several early manuscript copies and drafts of the Declaration have been preserved. Jefferson kept a four-page draft that late in his life he called the "original rough draft" . It is not known how many drafts Jefferson wrote before this or how much of the text was contributed by other members of the committee.. Boyd discovered a fragment of an older draft in Jefferson's handwriting in 1947. Like Adams, Jefferson sent copies of the document to his friends, albeit with slight modifications.

During the drafting process, Jefferson showed the draft to Adams and Franklin, and possibly other committee members, who made some additional changes. For example, Becker suspects that Franklin may have been responsible for changing Jefferson's original phrase " we hold these truths to be sacred and undeniable " to "we hold these truths self-evident " (we hold these truths to be sacred and undeniable). truths to be self-evident); however, historian Boyd questions Becker's hypothesis. Jefferson incorporated these changes in the copy submitted to Congress on behalf of the committee on June 28.

In 1823, Jefferson wrote a letter to Madison in which he recounted the writing process. After making the modifications to his draft—as Franklin and Adams suggested—he recalled: "I then prepared a fair copy, presented it to committee, and [later] from them, unaltered, to Congress" (I then wrote a fair copy, reported it to the Committee, and from them, unaltered, to Congress). This testimony remains unproven, because these documents have been lost or destroyed in the printing process or during debates to comply with the confidentiality rule of Congress.

On 21 April 2017, a second handwritten copy was found in an archive in Sussex. Named the "Sussex Declaration" by its discoverers, it differs from the National Archives copy (which they call the "Matlack Declaration") because the signatures on the former are not grouped by state. There are no records of how it arrived in England, but the discoverers suggest that the randomness of the signatures is related to an anecdote by signatory James Wilson, who had firmly maintained that the Declaration "was not made by the states, but by all the people.".

Posterity

The Declaration was abandoned in the years following the American Revolution, as it had served its original purpose of announcing the independence of the United States. Early Independence Day celebrations largely ignored it, as did early Independence Day celebrations. events of the Revolution. The act of proclaiming independence was considered important, while the text announcing this fact attracted little attention. The Declaration was rarely mentioned during debates on the United States Constitution, and its words were not incorporated into that document.George Mason's draft of the Virginia Declaration of Rights was more influential and its wording inspired the core ideas of state constitutions and laws rather than Jefferson's words. " In none of these documents", Pauline Maier concluded, "there is some evidence that the Declaration of Independence lived in the minds of men as a classic proclamation of American political principles.

Inspiration in other countries

Many leaders of the French Revolution admired the American emancipation act, but were also interested in the new state constitutions of that country. The influence and content of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (1789) arose largely part of the ideals of the American Revolution. Its main drafts were prepared by the Marquis de La Fayette, who had worked with his friend Thomas Jefferson in Paris. Language from George Mason's Virginia Declaration of Rights was also incorporated.However, although the preamble of the French Declaration is inspired by that of the American emancipation act, it ignores the right of "pursuit of happiness", that is, the one that refers to the notions of utility or public interest; on the other hand, both texts invoke a right to insurrection against oppressive governments and foreign tutelary powers.

The Declaration also influenced the Russian Empire, having a particular impact on the Decembrist revolt and other Russian thinkers. The historian Nikolai Bolhovitinov concluded that the American Revolution "provoked a sharp negative reaction from the ruling classes" in Russia and probably in other European states, as an effect of the severe blow to the British Empire. However, it was impossible to talk about the changes in the political structure of Russia, the potential for revolution or democratic freedoms during this period. An example of this was the prohibition of the distribution and translation of the document, a rule that was in force until the political reform of Alexander II.

According to historian David Armitage, the Declaration of Independence proved to be widely publicized internationally—although not as a proclamation of human rights— and was the first of a new genre of emancipation acts that heralded the creation of new sovereign states. Other French leaders were directly inspired by the text of the document. The Manifesto of the Province of Flanders (1790) was the first foreign derivation of the Declaration; thus, the Declaration of Independence of Venezuela (1811), the Declaration of Independence of Liberia (1847), the proclamations of secession of the United States appeared. Confederates of America (1860-1861) and the Vietnam Proclamation of Independence (1945).These echoed the American Emancipation Act by announcing the independence of a new state, without necessarily endorsing the political philosophy of the original.

Other countries have used the Declaration as a reference or have directly copied sections of it. The list includes the Declaration of Haiti of January 1, 1804 —in the midst of the Haitian Revolution—, the United Provinces of New Granada (1811), the Declaration of Independence of Argentina (1816), the Act of Independence of Chile (1818), Costa Rica (1821), El Salvador (1821), Guatemala (1821), Honduras (1821), Mexico (1821), Nicaragua (1821), Peru (1821), Bolivia (1825), Uruguay (1825), Ecuador (1830), Colombia (1831), Paraguay (1842), Dominican Republic (1844), the Texas Declaration of Independence (March 1836), the California Republic (July 1836),Hungary (1849), New Zealand in 1835, and Czechoslovakia (1918). The Unilateral Declaration of Independence of Rhodesia (ratified in November 1965) was also based on the American one; however, it omits phrases such as "all men are created equal" and "consent of the governed". South Carolina. 's

Resurgence of interest

In the United States, interest in the Declaration revived in the 1790s with the rise of the first political parties. Throughout the 1780s, few Americans knew or cared who wrote the act, but in For the next decade, "Jeffersonian Republicans" sought political advantage over their rivals—the Federalists—by promoting the importance of the Declaration and of Jefferson as its author.Federalists responded by questioning Jefferson's authorship or originality and emphasized that independence was declared by the entire Congress and Jefferson was only one member of the drafting committee. They also insisted that the proclamation itself—in which Federalist John Adams had played a major role—was more important than the document announcing it. However, this view lost steam—as did the Federalist Party—and before long the proclamation of independence became synonymous with the written act.

A less partisan recognition of the Declaration emerged in the years after the War of 1812, due to growing nationalism and a renewed interest in the history of the Revolution. In 1817, Congress commissioned John Trumbull to paint the session of the June 28, 1776, which was on display in several cities before being permanently installed in the federal Capitol. Earlier memorial paintings also appeared around this time, giving citizens their first glimpse of the signed document. Collective biographies of the signers were first published in the 1820s, something Garry Wills called the "cult of the signers".In subsequent years, more stories were published about the drafting and signing of the document.

Although interest in the Declaration resurfaced, the sections considered paramount in 1776 were no longer relevant: the announcement of the independence of the United States and the 25 Complaints against King George III. However, the second paragraph was valid even after the end of the war of independence, since it contains a discourse of evident truths and inalienable rights. The Constitution and the Bill of Rights lacked extensive expositions on rights and equality, which caused groups advocating those claims turned to the emancipation act for support. Beginning in the 1820s, variations of the Declaration were issued in support of the rights of workers, farmers, women, and others.For example, in 1848 the Seneca Falls Convention on the Rights of Woman stated that "men and women are created equal".

Slavery and "all men are created equal"

The apparent contradiction between the statement "all men are created equal" and the existence of the slave apparatus was hotly debated in political and intellectual circles when the Declaration was first published. As mentioned above, Jefferson had included a paragraph in his initial draft that pointed strongly to Britain's role in the slave trade, but it was removed from the final version; nonetheless, this politician was a major slaveholder in Virginia and owner of hundreds of slaves.Referring to this apparent inconsistency, the English abolitionist Thomas Day wrote in a 1776 missive: "If there is one truly ridiculous thing in nature it is an American patriot, who signs resolutions of independence with one hand and with the other wields a whip over his frightened slaves.

In the 19th century, the Declaration took on special significance for the abolitionist movement. Historian Bertram Wyatt-Brown argued that "abolitionists tended to interpret the Declaration of Independence as a theological and political document." Leading abolitionists Benjamin Lundy and William Lloyd Garrison adopted the "twin rocks" of "the Bible and the Declaration of Independence." Independence» as pillars of their philosophies. "As long as there is a single copy of the Declaration of Independence, or the Bible, in our land," Garrison wrote, "we will not despair."For radical abolitionists like Garrison, the most important part of the Emancipation Act was its affirmation of the right to revolution. Garrison called for the destruction of the government under the Constitution and the creation of a new state according to the principles of the Declaration. Following this line, historian Joseph A. Ellis concluded that in 1787 the Revolutionary War generation had formed a government of limited powers that tried to embody the ideal of the Continental Congress, but "burdened with the only legacy that defied the principles of 1776": human slavery.

The controversy over admitting more pro-slavery states into the Union coincided with the growing appreciation of the Emancipation Act. The first major public debate about slavery and the Declaration took place during the Missouri Compromise of 1819–1821. Anti-slavery congressmen argued that the language of the act indicated that the founding fathers had opposed slavery in principle, for which should not allow the existence of slave states in the country. The pro-slavery congressmen - led by Senator Nathaniel Macon (North Carolina) - responded that the Declaration was not part of the Constitution and, therefore, had no relevance to the question.This caused an ideological schism in the Democratic-Republican Party years later: Northern Jeffersonian Republicans embraced the anti-slavery legacy, while their Southern colleagues renounced the egalitarian view of the document.

With the anti-slavery movement gaining momentum, advocates of slavery—including John Randolph and John C. Calhoun—claimed that the Declaration's phrase "all men are created equal" was false, or at least did not apply to slaves. African-Americans. For example, during the debate over the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1853, Senator John Pettit (Indiana) said that the phrase was not an "obvious truth", but an "obvious lie". The law—Salmon P. Chase, Benjamin Wade, and others—defended the Declaration and what they saw as its anti-slavery principles.

Lincoln's Interpretation

The Declaration's relationship to slavery was taken up in 1854 by Abraham Lincoln, a little-known former congressman who idolized the founding fathers. Lincoln thought that the Emancipation Act expressed the loftiest principles of the American Revolution and that the forerunners of the The Declaration and the Constitution had tolerated slavery in the expectation that it would eventually wither away. He further concluded that if the Union legitimized the expansion of slavery in the Kansas-Nebraska law, it would be repudiating the foundations of the revolution. In his Peoria speech (October 1854), Lincoln said:

Nearly eighty years ago we began by declaring that all men are created equal; but now from that beginning we have run down to the other declaration, that for some men to enslave others is a "sacred right of self-government"… Our republican robe is soiled and trailed in the dust… Let us repurify it. Let us re-adopt the Declaration of Independence, and with it, the practices, and policy, which harmonize with it… If we do this, we shall not only have saved the Union: but we shall have saved it, as to make, and keep it, forever worthy of the saving.Nearly eighty years ago we began by declaring that all men are created equal; but now from that beginning we have run to the other statement, that for some men to enslave others is a "sacred right of self-government." [...] Our republican cloak is dirty and dragged on the ground. [...] We are going to readopt the Declaration of Independence and, with it, the practices and policies that harmonize with it. [...] If we do this, we will not only have saved the Union: we will have protected it, as well as created and preserved it, forever worthy of salvation.

The meaning of the Declaration was a recurring theme in the famous debates between Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas in 1858. Douglas maintained that the phrase "all men are created equal" in the Declaration referred only to white men. Furthermore, he inferred that the purpose had been simply to justify the independence of the United States and not to proclaim the equality of some "inferior or degraded race". On the contrary, Lincoln responded that the language of the Declaration was deliberately universal and established a moral standard. to which the American republic should aspire: "I have thought that the Declaration contemplated the progressive improvement in the condition of men everywhere." During the seventh and final debate with Douglas at Alton (October 15, 1858), Lincoln said:

I think the authors of that notable instrument intended to include all men, but they did not mean to declare all men equal in all respects. They did not mean to say all men were equal in color, size, intellect, moral development, or social capacity. They defined with tolerable distinctness in what they did consider all men created equal—equal in "certain inalienable rights, among which are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness." This they said, and this they meant. They did not mean to assert the obvious untruth that all were then actually enjoying that equality, or yet that they were about to confer it immediately upon them. In fact, they had no power to confer such a boon. They meant simply to declare the right, so that the enforcement of it might follow as fast as circumstances should permit. They meant to set up a standard maxim for free society which should be familiar to all, constantly looked to, constantly labored for, and even, though never perfectly attained, constantly approximated, and thereby constantly spreading and deepening its influence, and augmenting the happiness and value of life to all people, of all colors, everywhere.I believe that the authors of that remarkable instrument intended to include all men, but they did not intend to declare men equal in all respects. They did not mean that men were equal in color, size, intellect, moral development, or social ability. They defined with tolerable clarity what they considered men to be equal in "certain unalienable rights, among which are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness." This they said and this they pretended. They did not want to state the patent falsehood that everyone enjoyed such equality or that they were about to confer it immediately. In fact, they had no power to grant such a benefit. They simply intended to declare the right, so that its application could proceed as quickly as circumstances permitted.

According to Pauline Maier, Douglas's interpretation was historically accurate, but Lincoln's view ultimately prevailed: "In the hands of Lincoln, the Declaration of Independence became [for] the first [time] and foremost a living document" with " a set of goals to be achieved over time.

| [T]here is no reason in the world why the negro is not entitled to all the natural rights enumerated in the Declaration of Independence, the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. I hold that he is as much entitled to these as the white man.Translation [show]—Abraham Lincoln (1858). |

Like Daniel Webster, James Wilson, and Joseph Story before him, Lincoln argued that the Emancipation Act was a founding document of the United States and that this had important implications for the interpretation of the Constitution, which was ratified more than a decade ago. after the Declaration. The Constitution does not use the word "equality" , but Lincoln believed that the concept that "all men are created equal" remained a part of the founding principles of the nation.He expressed this thought in the opening sentence of his Gettysburg Address (1863): "Four score and seven years ago [i.e., in 1776] our fathers brought forth, upon this continent, a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that men are created equal.

Lincoln's point of view became influential and became a moral guide for interpreting the Constitution. In 1992, Garry Wills concluded that "for most people, the Declaration now means what Lincoln told us it means, as a way to correct the Constitution itself without overturning it." Lincoln admirers—such as Harry V. Jaffa — praised this promotion. Instead, critics—particularly Willmoore Kendall and Mel Bradford—claimed that Lincoln dangerously expanded the powers of the national government and violated the rights of states by trying to project the Declaration into the Constitution.

Seneca Falls Declaration

In July 1848, the first women's rights convention—the Seneca Falls Convention—was held in Seneca Falls, organized by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott, Mary Ann M'Clintock, and Jane Hunt. In their "Declaration of Sentiments" (Declaration of Sentiments) -inspired by the emancipation act-, the members of the convention demanded social and political equality for women and mentioned a list of grievances against them, similar to the accusations against Jorge III. His motto was "men and women are created equal" (all men and women are created equal) and the convention required access to suffrage for women. The movement was supported by William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass.

In popular culture

The passage of the Declaration of Independence was dramatized in a scene from the Tony Award-winning musical 1776 and in the 1972 film of the same name, as well as in the four-time Globe-winning television miniseries John Adams (2008). Gold and thirteen Emmys.

In 1971, the Declaration became the first digitized text by Michael Hart, inventor of the electronic book and founder of Project Gutenberg.

In 1984, the monument to the 56 signatories of the Declaration was unveiled in the Constitution Gardens of the National Mall in Washington DC, where the signatures of the signers are carved in stone with their names, places of residence, and occupations.

The Declaration of Independence (John Trumbull, 1819), a painting displayed in the United States Capitol Rotunda, appears on the back of the two-dollar bill (1976). The oil painting is sometimes incorrectly described as the signing of the Declaration, but it actually shows the five-member drafting committee presenting its draft to Congress—an event that took place on June 28, 1776—and not the signing of the document, which it happened days later.

In 2014, the One World Trade Center building in Lower Manhattan, with a height of 1,776 feet (541 m), was inaugurated to commemorate the year in which the emancipation act was signed.

Contenido relacionado

GM-NAA I/O

Donation of Pepin

Kingdom of Iberia