Culture

The term culture (from the Latin cultūra) has many interrelated meanings, that is, it is a polysemous term. For example, in 1952, Alfred Kroeber and Clyde Kluckhohn compiled a list of 164 definitions of culture in Culture: A Critical Review of Concepts and Definitions, and have classified more than 250 different. In everyday usage, the word culture is used for two different concepts:

- Excellence in taste for beautiful arts and humanities, also known as high culture.

- The sets of knowledge, beliefs and guidelines of conduct of a social group, including the material means used by its members to communicate with one another and to resolve needs of all kinds.

Nature and culture

A first distinction in scientific knowledge is established between nature and culture. This distinction means that the world of nature is the one that has not been created by man, at least in his origins; while culture is the world created by human beings, as explained at length in the magnificent book The Man-Made World ().

When the term culture arose in Europe, between the 18th and 19th centuries, it referred to a process of technology or improvement, as in agriculture or horticulture. In the 19th century, it first came to refer to the improvement or refinement of the individual, especially through education, and then to the achievement of national aspirations or ideals. In the mid-19th century, some scientists used the term "culture" to refer to universal human capacity. For the German anti-positivist and sociologist Georg Simmel, culture referred to "the cultivation of individuals through the interference of external forms that have been objectified in the course of history".

In the 20th century, "culture" emerged as a central concept of anthropology, encompassing all human phenomena They are not the total result of genetics. Specifically, the term "culture" in American anthropology has two meanings: (1) the evolved human capacity to classify and represent experiences with symbols and to act imaginatively and creatively; and (2) the different ways in which people live in different parts of the world, classifying and representing their experiences and acting creatively. After World War II, the term became important, albeit with different meanings, in other disciplines such as cultural studies, organizational psychology, sociology of culture, and management studies.

Some ethologists have spoken of "culture" to refer to customs, activities, or behaviors transmitted from one generation to another in groups of animals by conscious imitation of such behaviors.[citation needed] The beliefs and practices of a given culture can be exercised as control mechanisms that limit social behavior. Culture is associated with freedom, since it is the vehicle between knowledge and new forms of consciousness that allow a destabilization in hegemony. In addition, it can be recognized as sets or ways of life and customs of an era or social group. The term culture can reach extension and diverse uses, such as cultural diversity, object of empirical knowledge, and cultural difference.

Other concepts of culture:

- The word culture is associated with the action of cultivating or practising something, also according to the SAR can be the result or effect of prevailing human knowledge and set of ways of life.

- Culture has been seen within modernity projects.

- A dimension and expression of human life is realized through the use of symbols and artifacts, in which there is a field of production, circulation and consumption of signs and as a praxis that is articulated in a theory.

- In the dictionary different types of cultures are named and among them the two most emblematic are popular culture and mass culture.

Formation of the concept of culture

Etymology

The etymology of the modern concept “culture” has an ancient origin. In several European languages, the word “culture” is based on the Latin term used by Cicero, in his Tusculanae Disputationes, who wrote about a cultivation of the soul or “animi culture”, thus using an agricultural metaphor to describe the development of a philosophical soul, which was teleologically understood as one of the highest possible ideals for human development. Samuel Pufendorf took this metaphor to a modern concept, with a similar meaning, but no longer assuming that philosophy is the natural perfection of man. For this author, the meanings of culture, which many later writers take up, "refer to all the ways in which humans begin to overcome their original barbarism and, through artifice, become fully human."

As Velkley describes it:

The term “culture”, which originally meant the cultivation of the soul or the mind, acquires most of its later meanings in the writings of the 18th century German thinkers, who at various levels developed Rousseau’s criticism of modern liberalism and Enlightenment. Moreover, a contrast between “culture” and “civilization” is usually implied by these authors, even if they do not express it this way. Two primary meanings of culture arise from this period: culture as a folkloric spirit with a unique identity, and culture such as the cultivation of spirituality or free individuality. The first meaning is predominant within our current use of the term “culture”, but the second still plays an important role in what we believe should achieve culture, such as the full “expression” of the unique and “authentic” being.

Classical conception of culture

The term culture comes from the Latin cultus, which in turn derives from the word colere, which means care of the field or livestock. Around the XIII century, the term was used to designate a cultivated plot, and three centuries later its meaning of status had changed from a thing to the action that leads to said state: the cultivation of the land or the care of the cattle (Cuche, 1999: 10), approximately in the sense in which it is used in Spanish today in words such as agriculture, beekeeping, fish farming and others. By the middle of the XVI century, the term acquired a metaphorical connotation, like the cultivation of any faculty. In any case, the figurative meaning of culture did not extend until the XVII century, when it also appears in certain academic texts.

The Age of Enlightenment (XVIII century) is the time in which the figurative sense of the term as “cultivation of spirit" is imposed in broad academic fields. For example, the Dictionnaire de l'Académie Française of 1718. And although the Encyclopedia includes it only in its restricted sense of cultivating land, it does not ignore the figurative sense, which appears in the articles dedicated to to literature, painting, philosophy and science. With the passage of time, as a culture, the formation of the mind will be understood. That is, it becomes again a word that designates a state, although this time it is the state of the human mind, and not the state of the parcels.

The classic opposition between culture and nature also has its roots in this era. In 1798, the Dictionnaire included a meaning of culture in which the “natural spirit” was stigmatized. For many of the thinkers of the time, such as Jean Jacques Rousseau, culture is a distinctive phenomenon of human beings, which places them in a different position from other animals. Culture is the set of knowledge and knowledge accumulated by humanity throughout its millennia of history. As a universal characteristic (the word), it is used in a singular number, since it is found in all societies without distinction of ethnic groups, geographical location or historical moment.

Culture and civilization

It is also in the context of the Enlightenment that another of the classic oppositions in which culture is involved arises, this time, as a synonym for civilization. This word appears for the first time in the French language of the XVIII century, and with it the refinement of customs was meant. Civilization is a term related to the idea of progress. According to this, civilization is a state of Humanity in which ignorance has been defeated and customs and social relations are at their highest expression. Civilization is not a finished process, it is constant, and implies the progressive improvement of laws, forms of government, knowledge. Like culture, it is also a universal process that includes all peoples, even the most backward in the line of social evolution. Of course, the parameters used to measure whether a society was more civilized or more savage were those of their own society. At the dawn of the 19th century, both terms culture and civilization were used in almost the same way, especially in French and English. (Thompson, 2002: 186).

It is necessary to point out that not all French intellectuals used the term. Rousseau and Voltaire were reluctant to this progressive conception of history. They tried to propose a more relativistic version of history, although without success, since the dominant current was that of the progressives. It was not in France, but in Germany where the relativist positions gained greater prestige. The term Kultur in a figurative sense appears in Germany around the XVII century -with approximately the same connotation that in french For the 18th century it enjoys great prestige among German bourgeois thinkers. This was because it was used to insult aristocrats, whom they accused of trying to imitate the “civilized” ways of the French court. For example, Immanuel Kant pointed out that "we cultivate ourselves through art and science, we civilize ourselves [by acquiring] good manners and social refinements" (Thompson, 2002: 187). Therefore, in Germany the term civilization was equated with courtly values, described as superficial and pretentious. On the contrary, culture was identified with the deep and original values of the bourgeoisie (Cuche, 1999:13).

In the process of social criticism, the emphasis on the culture/civilization dichotomy shifts from differences between social strata to national differences. While France was the scene of one of the most important bourgeois revolutions in history, Germany was fragmented into multiple states. Therefore, one of the tasks that German thinkers had set themselves was political unification. National unity also involved the claim of national specificities, which the universalism of French thinkers sought to erase in the name of civilization. Already in 1774, Johann Gottfried Herder proclaimed that the genius of each people (Volksgeist) was always inclined towards cultural diversity, human richness and against universalism. For this reason, national pride lay in culture, through which each people had to fulfill a specific destiny. Culture, as Herder understood it, was the expression of diverse humanity, and did not exclude the possibility of communication between peoples.

During the 19th century, in Germany the term culture evolved under the influence of nationalism. Meanwhile, in France, the concept was expanded to include not only the intellectual development of the individual, but that of humanity as a whole. From here, the French meaning of the word presents a continuity with that of civilization: despite the German influence, the idea persists that beyond the differences between "German culture" and "French culture" (to give an example), there is something that unifies them all: human culture.

Definitions of culture in social disciplines

For the purposes of the social sciences, the first meanings of culture were constructed at the end of the XIX century. At this time, sociology and anthropology were relatively new disciplines, and the pattern in the debate on the subject that concerns us here was led by philosophy. Early sociologists, such as Émile Durkheim, rejected the use of the term. It must be remembered that in his perspective, the science of society had to address problems related to the social structure. Although it is a general opinion that Karl Marx left culture aside, this is refuted by the author's own works, holding that the social relations of production (the organization adopted by human beings for work and the social distribution of its fruits) constitute the basis of the legal-political and ideological superstructure, but in no case a secondary aspect of society. A social relation of production is inconceivable without rules of conduct, without legitimizing discourses, without practices of power, without customs and permanent habits of behavior, without objects valued by both the ruling class and the dominated class. The unveiling of Marx's youthful works, both The German Ideology (1845-1846) in 1932 by the famous edition of the Marx-Engels Institute of the USSR under the direction of David Riazanov, and the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts (1844) made it possible to that several supporters of his theoretical proposals developed a Marxist theory of culture (see below).

Generally, the meaning of culture is related to anthropology, one of the most important branches of the social discipline that deals precisely with the comparative study of culture. Perhaps because of the centrality that the word has in the theory of anthropology, the term has been developed in various ways, which involve the use of an analytical methodology based on premises that are sometimes far from each other. It was Franz Boas, against this ethnocentric company, who brought about the great epistemological change in anthropology. Starting with Boas, father of cultural relativism, the anthropologist becomes a translator, being able to enter the worldview of the student and understand the world of its meanings. This world of meaning will slowly lead to a concept that is not anthropological, and that is the social construction of meaning. Faced with this increased sensitivity linked to language issues, new disciplines will be developed, linked to the world of human meaning and language, which will complete the idea of culture understood from the world of meaning.

According to UNESCO's Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity, "culture should be considered as the set of distinctive spiritual and material, intellectual and affective features that characterize a society or a social group and that It encompasses, in addition to arts and letters, ways of life, ways of living together, value systems, traditions and beliefs"

British and American ethnologists and anthropologists at the turn of the 19th century took up the debate about the content of culture. These authors almost always had a professional training in law, but were particularly interested in the workings of the exotic societies that the West was encountering at the time. In the opinion of these pioneers of ethnology and social anthropology (such as Bachoffen, McLennan, Maine and Morgan), culture is the result of the historical evolution of society. But the history of humanity in these writers was strongly indebted to the Enlightenment theories of civilization, and above all, to Spencer's social Darwinism.

Descriptive definitions of culture

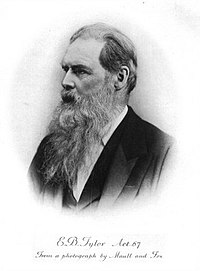

Definition of Tylor

As Thompson (2002:190) points out, the descriptive definition of culture was present in those first authors of nineteenth-century anthropology. The main interest in the work of these authors (which addressed problems as diverse as the origin of the family and matriarchy, and the survival of ancient cultures in the Western civilization of their time) was the search for the motives that led the peoples to behave in this or that way. In those explorations, meditating, or between technology and the rest of the social system.

One of the most important ethnographers of the time was Gustav Klemm. In the ten volumes of his work Allgemeine Kulturgeschichte der Menschheit (1843-1852) he tried to show the gradual development of humanity through the analysis of technology, customs, art, tools, religious practices. A monumental work, since it included ethnographic examples of peoples from all over the world. Klemm's work was to have an echo in his contemporaries, determined to define the field of a scientific discipline that was being born. Some twenty years later, in 1871, Edward B. Tylor published in Primitive Culture one of the most widely accepted definitions of culture. According to Tylor, culture is:

...that any complex which includes knowledge, beliefs, art, morals, law, customs, and any other habits and abilities acquired by man. The situation of culture in the various societies of the human species, to the extent that it can be investigated according to general principles, is an object suitable for the study of the laws of thought and the action of man.(Tylor, 1995: 29)

Thus, one of Tylor's main contributions was the elevation of culture as a matter of systematic study. Despite this notable conceptual advance, Tylor's proposal suffered from two major weaknesses. On the one hand, he took his humanistic emphasis from the concept by turning culture into an object of science. On the other, his analytical procedure was too descriptive. In the text quoted above, Tylor states that "a first step in the study of civilization consists in dissecting it in detail, and classifying these into the appropriate groups" (Tylor, 1995:33). According to this premise, the mere compilation of the "details" would allow the knowledge of a culture. Once known, it would be possible to rank it from more to less civilized, a premise he inherited from the social Darwinists.

Definition of culturalists

Tylor's theoretical proposal was subsequently taken up and reworked, both in Great Britain and in the United States. In the latter country, anthropology evolved towards a relativist position, represented in the first instance by Franz Boas. This position represented a break with previous ideas about cultural evolution, especially those proposed by British authors and the American Lewis Henry Morgan. For the latter, against whom Boas directed his criticism in one of his few theoretical texts, the process of human social evolution (technology, social relations and culture) could be equated with the process of growth of an individual of the species. Therefore, Morgan equated savagery with the "infancy of the human species", and civilization, with maturity. Boas was extremely harsh with the proposals of Morgan and the rest of contemporary evolutionary anthropologists. What their authors called “theories” about the evolution of society, Boas described as “pure conjectures” about the historical ordering of “phenomena observed according to principles admitted [in advance]” (1964:184).

Boas's critique of evolutionists echoes the perspective of German philosophers such as Herder and Wilhelm Dilthey. The core of the proposal lies in his inclination to consider culture as a plural phenomenon. In other words, more than talking about culture, Boas talked about cultures. For most of the anthropologists and ethnologists attached to the American culturalist school, the state of the ethnographic art at the beginning of the XX century it did not allow the formation of a general theory on the evolution of cultures. Therefore, the most important work of the students of the phenomenon should be the ethnographic documentation.In fact, Boas wrote very few theoretical texts, in comparison with his monographs on the indigenous peoples of the Pacific coast of North America.

The anthropologists trained by Robin Reid had to inherit many of the premises of their teacher. Among other notable cases, there is that of Ruth Benedict. In her work Patterns of culture (1939), Benedict points out that each culture is a whole understandable only in its own terms and constitutes a kind of matrix that gives meaning to the actions of individuals in a society. Alfred Kroeber, returning to the opposition between culture and nature, also pointed out that cultures are phenomena sui generis but, strictly speaking, they were of a category outside of nature. Therefore, according to Kroeber, the study of cultures had to get out of the domain of the natural sciences and face the former for what they were: superorganic phenomena. Melville Herskovits and Clyde Kluckhohn took up their scientific definition of the study of culture from Tylor.. For the first, the collection of defining traits of cultures would also allow their classification. Although, in this case, the classification was not carried out in a diachronic sense, but rather in a spatial-geographical sense that would allow knowledge of the relationships between the different peoples settled in a cultural area. Kluckhonn, for his part, summarizes in his text Anthropology most of the postulates seen in this section, and claims the cultural domain as the specific field of anthropological activity.

For his part, Javier Rosendo describes culture as the set of traits that characterize a region or group of people, with respect to the rest, which can change according to the time in which they live. These traits can encompass dance, traditions, art, costumes, and religion.

Functionalist-structural definition

The most peculiar characteristic of the functionalist concept of culture refers precisely to its social function. The basic assumption is that all the elements of a society (among which culture is one more) exist because they are necessary. This perspective has been developed both in anthropology and sociology, although its first characteristics were undoubtedly outlined involuntarily by Émile Durkheim. This French sociologist rarely used the term as the main analytical unit of his discipline. In his book The rules of the sociological method (1895), he states that society is made up of entities that have a specific function, integrated into a system analogous to that of living beings, where each organ is specialized in the fulfillment of a vital function. In the same way that the organs of a body are susceptible to disease, institutions and customs, beliefs and social relations can also fall into a state of anomie. Durkheim and his followers, however, do not deal exclusively or mainly with culture as an object of study, but rather with social facts. Despite them, his analytical proposals were taken up by conspicuous authors of British social anthropology and the sociology of culture in the United States.

Later, the Pole Bronislaw Malinowski took up both Tylor's description of culture and some of Durkheim's approaches to social function. For Malinowski, culture could be understood as a "sui generis reality" that should be studied as such (in his own terms). In the category of culture it included artifacts, goods, technical processes, ideas, habits and inherited values (Thompson, 2002: 193). He also considered that social structure could be understood analogously to living organisms, but unlike Durkheim, Malinowski had a more holistic bent. Malinowski believed that all elements of culture had a function that gave them meaning and made their existence possible. But this function was not given only by the social, but by the history of the group and the geographical environment, among many other elements. The clearest reflection of this thought applied to theoretical analysis was the book The Argonauts of the Western Pacific (1922), an extensive and detailed monograph on the different spheres of culture of the Trobriand islanders, a people who inhabited the Trobriand Islands, east of New Guinea.

Years later, Alfred Reginald Radcliffe-Brown, also a British anthropologist, would take up some of Malinowski's proposals, and especially those that referred to the social function. Radcliffe-Brown rejected that the field of analysis of anthropology was culture, rather it was in charge of the study of the social structure, a network of relationships between people in a group. However, he also analyzed those categories that had been previously described by Malinowski and Tylor, always following the principle of scientific analysis of society. In his book Structure and Function in Primitive Society (1975) Radcliffe-Brown establishes that the most important function of social beliefs and practices is to maintain social order, balance in relationships, and significance of the group over time. His proposals were later taken up by many of his students, especially by Edward Evan Evans-Pritchard, an ethnographer of the Nuer and Azande, peoples of central Africa. In both ethnographic works, the regulatory function of social beliefs and practices is present in the analysis of these societies, the first of which Evans-Pritchard called "ordered anarchy."

Symbolic definitions

The origins of symbolic conceptions of culture go back to Leslie White, an American anthropologist trained in the culturalist tradition of Boas. Despite the fact that in his book The Science of Culture he affirms, at first, that this is «the name of a precise type or class of phenomena, that is, the things and events that depend of the exercise of a mental ability, exclusive to the human species, which we have called "symbolizing", in the course of his text, White will gradually abandon the idea of culture as symbols to focus on an ecological perspective.

Structuralist definition

Structuralism is a more or less widespread current in the social sciences. Its origins go back to Ferdinand de Saussure, a linguist, who proposed grosso modo that language is a system of signs. After his conversion to anthropology (as he calls it in Sad Tropics), Claude Lévi-Strauss –influenced by Roman Jakobson– would return to this concept for the study of facts of anthropological interest, among which culture was just one more. According to Lévi-Strauss, culture is basically a system of signs produced by the symbolic activity of the human mind (a thesis that he shares with White).

In Structural Anthropology (1958) Lévi-Strauss will define the relationships that exist between the signs and symbols of the system, and their function in society, without paying too much attention to this last point. In summary, it can be said that in the structuralist theory, culture is a message that can be decoded both in its contents and in its rules. The message of culture speaks of the conception of the social group that creates it, it speaks of its internal and external relations. In The Savage Thought (1962), Lévi-Strauss points out that all the symbols and signs of which culture is made are products of the same symbolic capacity that all human minds possess. This ability basically consists of classifying things in the world into groups, to which certain semantic charges are attributed. There is no group of symbols or signs (semantic field) that does not have a complementary one. The signs and their meanings can be associated by metaphor (as in the case of words) or metonymy (as in the case of the emblems of royalty) to significant phenomena for the creative group of the cultural system. Symbolic associations are not necessarily the same in all cultures. For example, while in Western culture red is the color of love, in Mesoamerica it is the color of death.

According to the structuralist proposal, the cultures of “primitive” and “civilized” peoples are made of the same stuff and, therefore, the systems of knowledge of the external world that dominate in each —magic in the former, science in the latter—– are not radically different. Although there are several distinctions that can be established between primitive and modern cultures: one of the most important is the way in which they manipulate the elements of the system. While magic improvises, science proceeds on the basis of the scientific method. The use of the scientific method does not mean—according to Lévi-Strauss—that cultures where science is dominant are superior, or that those where magic plays a role a fundamental role are less rigorous or methodical in their way of knowing the world. Simply, they are of a different nature from each other, but the possibility of understanding between both types of cultures basically lies in a universal faculty of the human race.

In the structuralist perspective, the role of history in shaping a society's culture is not that important. The fundamental thing is to arrive at elucidating the rules that underlie the articulation of symbols in a culture, and observe the way in which these give meaning to the performance of a society. In various texts, Lévi-Strauss and his followers (such as Edmund Leach) seem to insinuate, like Ruth Benedict, that culture is a kind of pattern that belongs to the entire social group but is found in no one in particular. This idea was also taken up from the concept of language proposed by Saussure.

Definition of symbolic anthropology

Definition of symbolic anthropology

By believing as Max Weber that man is an animal suspended in plots of significance woven by himself, he considered that culture is composed of such plots, and that the analysis of it is therefore not an experimental science in search of laws, but an interpretative science in search of meaning.(Geertz, 1988:)

Under the above premise, Geertz and most of the symbolic anthropologists question the authority of ethnography. They point out that what anthropologists can limit themselves to is making "plausible interpretations" of the meaning of the symbolic plot that is culture, from the dense description of the greatest number of points of view that it is possible to know regarding the same event.. In another sense, the symbolic do not believe that all elements of the cultural fabric have the same meaning for all members of a society. Rather, they believe that they can be interpreted in different ways, depending either on the position they occupy in the social structure, on prior social and psychic conditioning, or on the context itself.

Marxist definitions

As previously stated, Karl Marx, despite the general opinion, paid attention to the analysis of cultural issues, specifically in its relationship with the rest of the social structure. According to Marx's theoretical proposal, the domain of the cultural (constituted above all by ideology) is a reflection of the social relations of production, that is, of the organization that human beings adopt in the face of economic activity. The great contribution of Marxism in the analysis of culture is that it is understood as the product of production relations, as a phenomenon that is not detached from the mode of production of a society. Likewise, it considers it as one of the means by which the social relations of production are reproduced, which allow the permanence in time of the conditions of inequality between the classes.

In its most simplistic interpretations, Marx's definition of ideology has given rise to a tendency to explain beliefs and social behavior in terms of the relationships established between those who dominate the economic system and their subordinates. However, there are many positions where the relationship between the economic base and the cultural superstructure is analyzed in broader approaches. For example, Antonio Gramsci draws attention to hegemony, a process through which a dominant group legitimizes itself before the dominated, and they end up seeing domination as natural and assuming domination as desirable. Louis Althusser proposed that the field of ideology (the main component of culture) is a reflection of the interests of the elite, and that through the ideological apparatuses of the State they are reproduced over time.

Likewise, Michel Foucault –in the well-known debate of November 1971 in the Netherlands with Noam Chomsky– answering the question of whether capitalist society was democratic, as well as answering in the negative –arguing that a democratic society is based on cash exercise of power by a population that is not divided or hierarchically ordered into classes- maintains that, in general, all education systems -which appear simply as transmitters of apparently neutral knowledge- are made to keep a certain social class in power, and exclude other social classes from the instruments of power.

Neo-evolutionary or eco-functionalist definition

Although the study of culture was born as a concern for the change of societies over time, the loss of prestige into which the first authors of anthropology fell was fertile ground for them to take root in reflection on culture. culture ahistorical conceptions. Except for the Marxists, interested in the revolutionary process towards socialism, the rest of the social disciplines did not pay much attention to the problem of cultural evolution.

To introduce the neoevolutionary definitions of culture, it is necessary to remember that the social evolutionists of the late XIX century (represented, among others, by Tylor), thought that the "primitive" societies of their time were residues of ancient cultural forms, through which the civilization of the West would necessarily have passed before becoming what it was at that time. As noted above, Boas and his disciples dismissed these arguments, pointing out that nothing proved the truth of these assumptions. In the United States, however, around the 1940s a further shift in anthropology's temporal focus took place. This new course is the neoevolucionista, interested among other things, by the socio-cultural change and the relations between culture and environment.

White and Steward

According to neoevolutionism, culture is the product of historical relations between a human group and its environment. In this way, the definitions of culture proposed by Leslie White (1992) and Julian Steward (1992), who led the neoevolutionary current at its birth, can be summarized. The emphasis of the new anthropological current moved from the functioning of culture to its dynamic character. This paradigm shift represents a clear opposition to structuralist functionalism, interested in the current functioning of society; and culturalism, which postponed historical analysis for a time when the ethnographic data allowed it.

Both Steward and White agree that culture is only one domain of social life. For White, culture is not a phenomenon to be understood on its own terms, as the culturalists proposed. The use of energy is the engine of cultural transformations: it stimulates the transformation of available technology, always tending to improve. Thus, culture is determined by the way in which the human group takes advantage of its environment. This use is translated in turn into energy. The development of a group's culture is proportional to the amount of energy that the available technology allows it to harness. Technology determines social relations and essentially the division of labor as a pristine form of organization. In turn, the social structure and the division of labor are reflected in the belief system of the group, which formulates concepts that allow it to understand the environment around it. A change in the technology and the amount of energy used translates, therefore, into changes in the whole.

Steward, for his part, took up from Kroeber the conception of culture as a fact that was above and outside of nature. However, Steward maintained that there was a dialogue between the two domains. He believed that culture is a phenomenon or capacity of the human being that allows him to adapt to his biological environment. One of the main concepts in his work is that of evolution. Steward argued that culture follows a process of multilinear evolution (that is, not all cultures pass from a savage state to barbarism, and from there to civilization), and that this process is based on the development of cultural types derived from cultural adaptations to the physical environment of a society. Steward introduces the term ecology into the social sciences, indicating with it: the analysis of the relationships between all organisms that share the same ecological niche.

Marvin Harris and Cultural Materialism

Within the type of ideas introduced by White and Steward, it is worth noting the cultural materialism advocated by Marvin Harris and other American anthropologists. This current can be assimilated to a form of ecofunctionalism in which certain divisions introduced by Marx fit. For cultural materialism, understanding cultural evolution and the configuration of societies basically depends on material, technological and infrastructural conditions. Cultural materialism establishes a triple division between groups of concepts that attend to their causal relationship. These groups are called: infrastructure (mode of production, technology, geographical conditions, etc.), structure (mode of social organization, hierarchical structure, etc.) and superstructure (religious and moral values, artistic creations, laws, etc.).

Cultural evolution

There was at least a great conceptual distance between White's and Steward's proposals. The first was inclined towards the study of culture as a total phenomenon, while the second remained more prone to relativism. For this reason, among the limitations that his successors had to overcome was that of concatenating both positions, to unify the theory of cultural ecology studies. Thus, Marshall Sahlins proposed that cultural evolution follows two directions. On the one hand, it creates diversity “through adaptive modification: the new forms differ from the old. On the other hand, evolution generates progress: the higher forms arise from the lower ones and surpass them."

The idea that culture transforms along two simultaneous lines was developed by Darcy Ribeiro, who introduced the concept of civilizational process to understand the transformations of culture.

Over time, neoevolutionism served as one of the main hinges between the social sciences and the natural sciences, especially as a bridge to biology and ecology. In fact, its own vocation as a holistic approach has made it one of the most interdisciplinary streams of disciplines that study humanity. Starting in the 1960s, ecology entered into a very close relationship with evolutionary cultural studies. Biologists had discovered that humans are not the only animals that possess culture: hints of it had been found among some cetaceans, but especially among primates. Roy Rappaport introduced into the discussion of the social the idea that culture is part of the very biology of the human being, and that the very evolution of the human being is due to the presence of culture. He pointed out that:

... superorganic or not, it must be borne in mind that culture itself belongs to nature. It emerged in the course of evolution through different natural selection processes only in part of those that produced the tentacles of the octopus [...] Although culture is highly developed in humans, recent ethological studies have indicated some symbolic capacity among other animals. [...] Although cultures can be imposed on ecological systems, there are limits for such impositions, as cultures and their components are subject to selective processes.(Rappaport, 1998: 273-274)

New discoveries in ethology (the science that studies animal behavior) encouraged many biologists to intervene in the sociological debate on culture. Some of them sought to establish relationships between human culture and primitive forms of culture observed, for example, among the macaques of Japan. One of the best known examples is that of Sherwood Washburn, professor of anthropology at the University of California. Leading a multidisciplinary team, he undertook the task of searching for the origins of human culture. As the first part of his project, he analyzed the social behavior of higher primates. Secondly, assuming that the !Kung Bushmen were the last redoubts of the most primitive forms of human culture, he proceeded to study their culture. The third stage of Washburn's program (in which Richard Lee and Irven de Vore collaborated, and which lasted through the first half of the 1960s) was to compare the results of both investigations, and speculate on this basis about of the importance of hunting in the construction of society and culture.

This hypothesis was presented at a conference called Man, the Hunter, held at the University of Chicago in 1966. It was because the research was based on premises about cultural evolution that had been discarded since time immemorial. de Boas, or because it was a thesis that denied the importance of women in the construction of culture, the thesis of Washburn, Lee and De Vore was not well received.

This definition addresses the main characteristic of culture, which is strictly a work of human creation, unlike the processes carried out by nature, for example, the movement of the earth, the seasons of the year, the rites mating of the species, the tides and even the behavior of the bees that make their honeycombs, make honey, orient themselves to find their way back but, despite that, do not constitute a culture, since all the bees in the world they do exactly the same thing, mechanically, and can't change anything. Exactly the opposite occurs in the case of human works, ideas and acts, since these transform or add to nature, for example, the design of a house, the recipe for a honey or chocolate sweet, the preparation of a plane, the simple idea of mathematical relationships, are culture and without human creation they would not exist by the work of nature.

In 1998, Jesús Mosterín published his book ¡Viva los animales!, where he explains what culture is:

Culture is not an exclusively human phenomenon, but is well documented in many species of nonhuman superior animals. And the criterion for deciding to what extent a certain pattern of behavior is natural or cultural has nothing to do with the level of complexity or importance of such conduct, but only with the manner in which the information relevant to its execution is transmitted. [...] Chimpanzees are very cultural animals. They learn to distinguish hundreds of plants and substances, and to know their food and astringent functions. Thus they manage to feed and counter the effects of parasites. They have very little instinctive or congenital behavior. There is no 'culture of chimpanzees' common to the species. Each group has its own social traditions, venatorias, food, sexual, instrumental, etc. [...] Culture is so important to the chimpanzees, that all attempts to reintroduce the chimpanzees raised in captivity in the jungle unfortunately fail. Chimpanzees don't survive. They lack culture. They don't know what to eat, how to act, how to interact with wild chimpanzees, who attack and kill them. They don't even know how to make their high nest-bed every night to sleep safely in a tree's cup. During the five years the little chimpanzee sleeps with his mother he has about 2,000 opportunities to observe how the nido-cama is made. Female chimpanzees separated from their group and raised with bottle at the zoo don't even know how to care for their own babies, even if they learn it if they see movies or videos of other chimpanzees raising(Jesus Mosterin, Live the Animals! 1998: 146-7, 151-2)

Definition of culture in the Catholic Church

The classic definition of culture in the Catholic Church is found in the Second Vatican Council:

The word culture indicates, in the general sense, everything that man defines and develops his innumerable spiritual and bodily qualities; he seeks to subject the same earthly orb with his knowledge and work; he makes social life more human, both in the family and in all civil society, through the progress of customs and institutions; finally, through the time he expresses, communicates and conserves in his works great spiritual experiences and aspirations to serve many, and even the benefit.(Dogmatic Constitution Gaudium et spes, 1965, n. 53)

In the definition, two aspects stand out: placing the individual at the center, culture being a product of man and at the service of man; and combining the formation of each person through culture, with the specific contribution of a community to the progress of humanity. This concept of culture is the basis for explaining the process of inculturation or insertion of the Catholic Church in a culture and expression of Christianity in a new modality and culturality.

The scientific concept of culture

From the beginning, the scientific concept of culture made use of ideas from information theory, from the notion of meme introduced by Richard Dawkins, from the mathematical methods developed in population genetics by authors such as Luigi Luca Cavalli- Sforza and advances in understanding the brain and learning. Various anthropologists, such as William Durham, and philosophers, such as Daniel Dennett and Jesús Mosterín, have contributed decisively to the development of the scientific conception of culture. Mosterín defines culture as the information transmitted by social learning between animals of the same species. As such, it is opposed to nature, that is, to the information transmitted genetically. If memes are the elementary units or pieces of acquired information, the current culture of an individual at a given moment would be the set of memes present in the brain of that individual at that moment. In turn, the vague notion of culture of a social group is analyzed by Mosterín in several different precise notions, all of them defined based on the memes present in the brains of the members of the group.

Culture industry

The cultural industry is defined by UNESCO as that which produces and distributes cultural goods or services which, «considered from the point of view of their specific quality, use or purpose, embody or transmit cultural expressions, regardless of the commercial value they may have have. Cultural activities can constitute an end in themselves, or contribute to the production of cultural goods and services."

Socialization of culture

The important contribution of the humanistic psychology of, for example, Erik Erikson with a psychosocial theory to explain the sociocultural components of personal development.

- Each member of the species could access it from a common source, without limiting, example of it: the knowledge transmitted by the parents.

- It must be able to be increased in subsequent generations.

- It must be universally shared by all those who possess rational and meaningful language.

Thus, the human being has the power to teach the animal, from the moment it is capable of understanding its rudimentary apparatus of gestures and sounds, carrying out new acts of communication; but animals cannot do something similar with us. We can learn from them through observation, as objects, but not through cultural exchange, that is, as subjects.

Classification

Culture is classified, with respect to its definitions, as follows:

- Topics: Culture consists of a list of topics or categories, such as social organization, religion or economy.

- Historic: Culture is the social heritage, it is the way humans solve problems of adaptation to the environment or to life in common.

- Mental: Culture is a complex of ideas, or habits learned, that inhibit impulses and distinguish people from others.

- Structure: Culture consists of ideas, symbols or behaviors, modeled or patterned and inter-related.

- Symbolic: Culture is based on the arbitrary meanings that are shared by a society.

Culture can also be classified as follows:

- According to its extension

- Universal: when it is taken from the point of view of an abstraction from the traits that are common in the societies of the world. For example, greeting.

- Total: made up of the sum of all the particular traits to the same society.

- Particular: equal to subculture; set of guidelines shared by a group that integrates into general culture and which in turn differs from them. E.g.: the different cultures in the same country.

- According to its development

- Primitive: that culture that maintains precarious technical development traits and that, because it is conservative, does not tend to innovation.

- Civilized: culture that is updated producing new elements that allow development to society.

- Analfabeta or pre-alphabeta: it is handled with oral language and has not incorporated the writing even partially.

- Alfabeta: culture that has incorporated both written and oral language.

- According to its dominant character

- Sensist: culture that is manifested exclusively by the senses and is known from them.

- Rational: culture where reason prevails and is known through its tangible products.

- Ideal: it is built by the combination of the sensist and rational.

- According to your address

- Posfigurative: that culture that looks at the past to repeat it in the present. Culture taken from our elders without variation. It is generational and is particularly given in primitive peoples.

- Configurative: the culture whose model is not the past, but the behavior of the contemporaries. Individuals mimic behavior modes of their peers and recreate their own.

Elements of culture

Culture shapes everything that involves transformation and following a lifestyle. The elements of culture are divided into:

a) Materials: These are all objects, in their natural state or transformed by human work, that a group is in a position to take advantage of at a given moment in their historical development: land, materials raw materials, energy sources, tools, utensils, natural and manufactured products, etc.

b) Organizational: These are the forms of systematized social relations, through which the participation of the members of the group whose intervention is necessary to carry out the action is made possible. The size and other demographic characteristics of the population are important data that must be taken into account when studying the organizational elements of any society or group.

c) Knowledge: These are the assimilated and systematized experiences that are elaborated, that is, the knowledge, ideas and beliefs that are accumulated and transmitted from generation to generation and within the framework of the which new knowledge is generated or incorporated.

d) Conduct: These are the behaviors or patterns of conduct common to a human group.

e) Symbolic: They are the different codes that allow the necessary communication between the participants in the different moments of an action. The fundamental code is language, but there are other significant symbolic systems that must also be shared for certain actions to be possible and effective.

f) Emotional: which can also be called subjective. They are the collective representations, beliefs and integrated values that motivate participation and/or acceptance of actions: subjectivity as an indispensable cultural element.

g) Guided: They are integrated systems. A person does not represent a culture, but rather a large group.

Within any culture there are two elements to take into account:

- Cultural traits: smaller and more significant portion of culture, which gives the profile of a society. All the features are always conveyed to the inside of the group and gain strength to then be externalized.

- Cultural complexes: they contain cultural traits in society.

Cultural Changes

Cultural changes: These are changes over time in all or some of the cultural elements of a society (or a part of it).

- Enculturation: it is the process in which the individual is cultured, that is, the process in which the human being, since he is a child, is cultured. This process is part of culture, and as culture constantly changes, so do the way and means with which it is culturalized.

- Aculturation: is usually given at the time of conquest or invasion. It is usually forcibly and imposed, like the conquest of America, the invasion of Iraq. Examples of results of this phenomenon: food (potaje, pozole), huipil. The opposite phenomenon is called deculturation, and consists of the loss of cultural characteristics due to the incorporation of other foreign countries.

- Transculturation: Transculturation is a phenomenon that occurs when a social group receives and adopts the cultural forms that come from another group.

- Inculturation: it occurs when the person integrates into other cultures, accepts and dialogues with the people of that particular culture.

Culture is based on all of us.

Cultural Art History

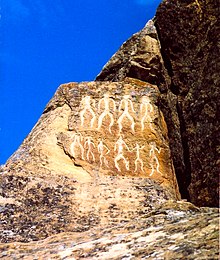

- Rupetic paint: The history of art began from the stone age dividing into the Paleolithic, Mesolytic and Neolithic, to the age of metals. It is considered a period in which the first manifestations considered to be artistic by the homo sapiens, called “ropestres” in the caves in the middle of 25000-8000 BC. In these paintings the hunt, agriculture and divinity were reflected, as their art was reflected in bone, wood and stone sculptures.

- hierarchical writing: In the old age the first signs of writing are developed due to the need to carry commercial and economic records. His first indication was the cuneiform writing that was practiced in clay tablets, based on pictographic and ideographic elements, followed by this appears the hieroglyphical writing based on the Hebrew language which was used as a method of writing the alphabet that related the fonemas to each symbol. At this stage there is Mesopotamian art, art of ancient Egypt, pre-Columbian art, African art, Indian art, and Chinese art.

- Classic art: In classical art it is developed in Greece and Rome, where human nature and harmony are represented, its bases come from Western art. Greek art is divided into three periods: archaic, classic and hellenistic. His paintings were developed more than all in ceramics. His Greek myths drew attention to the fusion of indogermanic and Mediterranean elements.

- Medieval art: In medieval art it is marked by the fall of the Roman Empire of the West. Classic art is reinterpreted so that Christianity as a new religion takes over most of the medieval art production. This art is divided into paleo-Christian art, Germanic art, pre-Roman art, Byzantine art, Islamic art, Romanesque art, Gothic art.

- Modern art: In the art of modern age it is usually given as a synonym for contemporary art which developed in the centuryXV and XVIII, their changes were made at the political, economic, social, and cultural level. His first appearance was with the lives of girgio vasari in the inaugural text of the study of art with historiographic character.

- Hilemorfist art: At this moment in our history we are experiencing a wide variety of changes not only sociopolitical but cultural. Likewise, the vision we have today of art has been modified by all these changes, and today we know what the “Hylemorfist Art” would be, which aims to break the conventional relationship between matter and form has been adopted by Latin American cultures as a measure of protest. Since in essence this hylemorphist sense what it seeks is to deconstruct the conception of conventional concepts created by this relation between matter and form, and give us the ability to think of other possibilities of the world. And as the famous painter and artist Luis Camnitzer says in his “Latin Concept”: Art must go to reality and transform it, replace it.

A clear example of this current hylemorphist art is Lotty Rosenfeld, a Chilean visual artist, attached to neo-avant-garde. Who through her works modifies reality, taking her art to the streets and transforming the conventional relationship that exists between matter and form. Such is “A thousand crosses on the pavement” That it was a work made at the time of the Chilean military dictatorship in which Rosenfeld drew a cross using the marking lines of the streets and placing a line cross-sectional for each disappeared person from the dictatorship, making a counterinformation to the traditional media of that time that denied the reality in which the country was consumed, and that did not give figures or statistics of the disappeared that there were.

Relation between culture and linguistics

An essential element of culture is language, there are cultural concepts within the different systems in which we find specific characteristics of grammar and lexicon. Therefore, including linguistics in the study of ancient and contemporary cultures is essential. The analysis of culture from linguistics in the last sixty years has evolved from structuralist thinking to cultural variation. Linguists have also developed research on intercultural communication, and have recently created new concepts such as multilingualism and multiculturalism to define new cultural phenomena.

Contenido relacionado

Paul Kirchoff

Match

KUKL