Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars promoted by the Catholic Church in the Middle Ages. Said military campaigns had the declared objective of recovering for Christianity the region of the Near East known as the Holy Land, which had been under the rule of Islam since the seventh century. In many cases, these crusades were the cause of persecution against Jews, Greek Orthodox Christians, and Russians. Crusaders, known as crusaders, took temporary religious vows and were granted leniency for their sins.

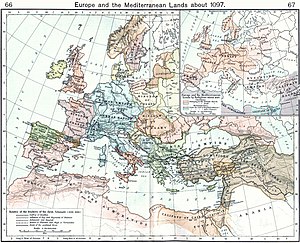

The Eastern Mediterranean crusades, the first to which this name was applied, were carried out by feudal lords and sovereigns of Western Europe, most notably those of Capetian France and the Holy Roman Empire, but also of England and Sicily, at the request of the Papacy and, in principle, of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire. They took place over a period of almost two centuries, between 1096 and 1291, led to the short-lived establishment of a Christian Kingdom in Jerusalem and the temporary conquest of Constantinople.

Other religiously sanctioned wars in Spain and Eastern Europe, some of which culminated in the 15th century, received the classification of crusades by the Church. Among these is the struggle of Christians against the Muslim rulers of Spanish territories; the forced Christianization of the pagan Slavic and Baltic peoples (Prussians and Lithuanians above all); the persecution against Catharists in the south of France and, in some cases, against the Byzantine Empire or the Ottomans.

About the reasons

The crusades were undertaken to liberate the "Holy Places," that is, the regions where Jesus Christ lived, from Muslim domination. Its origins date back to 1095, when the Byzantine Emperor Alexios I requested protection for Eastern Christians from Pope Urban II, who at the Council of Clermont began preaching the crusade. Ending his address with the Gospel phrase "renounce yourself, take up your cross, and follow me" (Matthew 16:24), the enthusiastic crowd noisily expressed their approval with the cry Deus lo vult, or God willing.

Possibly, the motivations of those who participated in them were very diverse, although in many cases a true religious fervor can be assumed. It is argued, for example, that they were motivated by the expansionist interests of the feudal nobility, the control of trade with Asia and the hegemonic desire of the papacy over the monarchies and churches of the East, even though they declared with principle and objective to recover the Holy Land. for pilgrims, whom the Seljuk and Zangid Turks, once Jerusalem was conquered in 1076, mercilessly abused, unlike the time of the Fatimid Caliphs (909-1171) whose rule was freedom of thought and reason extended to people, who could believe whatever they wanted, as long as they didn't infringe on the rights of others.

About the term

The origin of the word and why it was called that way is attributed to the cloth cross used as an insignia on the outer clothing of those who took part in this enterprise to reconquer the Holy Land.

Medieval writers use the terms crux (pro transmarine crossing, Statute of 1284, cited by Du Cange, s.v. crux), croisement (Joinville), croiserie (Monstrelet), etc. Since the Middle Ages, the meaning of the word crusade has been extended to include all wars waged in fulfillment of a vow and directed against infidels, e.g. eg against Muslims, pagans, heretics, or those under an edict of excommunication.

The wars that since the s. VIII d. C. maintained the Christian kingdoms of the north of the Iberian Peninsula against the Muslim Caliphate of Córdoba, and that historiography knows as the Reconquest, continued equally discontinuously from the century XI against the Taifa kingdoms, the Almoravids and the Almohads. On some occasions, the Pope qualified them as a "crusade", as happened with the battle of Las Navas de Tolosa (1212) or with the final episode of the Reconquest, the Granada war (1482-1492). Crusades were organized in northern Europe against the Prussians and Lithuanians. The extermination of the Albigensian heresy was due to a crusade, and in the 13th century, the popes preached crusades against John Landless and Frederick II Hohenstaufen.

But modern literature has abused the word by applying it to all religious wars, such as Heraclius's expedition against the Persians in the s. VII d. C. and the conquest of Saxony by Charlemagne. This term resonated again during the first half of the XX century, used by the Axis powers or their circle of influence: the Spanish civil war or the German invasion of the USSR, received such qualification by part of the official propaganda.

However, used with strict criteria, the idea of the crusade corresponds to a political conception that has only existed in Christianity since the XI to XV. It supposed a union of all the peoples and sovereigns under the direction of the popes. All the crusades were announced through preaching. After pronouncing a solemn vow, each warrior received a cross from the hands of the pope or from his legate, and was from that moment considered a soldier of the Church. Crusaders were also granted temporary indulgences and privileges, such as exemption from civil jurisdiction or the inviolability of persons and property. Of all those wars waged in the name of Christianity, the most important were the eastern crusades, which are the ones discussed in this article.

Background

In order to understand the reasons the leaders of Europe and the Middle East had for making such decisions, we must go back to the years immediately before the beginning of the crusader phenomenon and understand the antecedents of the crusades.

Around the year 1000, Constantinople stood as the most prosperous and powerful city in the "known world" in the West. Located in an easily defensible position, in the middle of the main trade routes, and with a centralized and absolute government in the person of the Emperor, as well as a capable and professional army, they made the city and the territories governed by it (the Byzantine Empire) a nation without equal in the entire world. Thanks to the actions undertaken by Emperor Basil II Bulgaroktonos, the enemies closest to its borders had been humiliated and totally nullified.

After Basil's death, however, less competent monarchs took over the Byzantine throne, while a new threat loomed on the horizon from Central Asia. They were the Turks, nomadic tribes who, in the course of those years, had converted to Islam. One such tribe, the Seljuk Turks (named after their mythical Selyuq leader), attacked the Empire of Constantinople. In the battle of Manzikert, in the year 1071, the bulk of the imperial army was devastated by the Turkish troops, and one of the co-emperors was captured. As a result of this debacle, the Byzantines had to cede most of Asia Minor (today the nucleus of the Turkish nation) to the Seljuks. Now there were Muslim forces posted just a few miles from Constantinople itself.

On the other hand, the Turks had also advanced in a southerly direction, towards Syria and Palestine. One after another the cities of the Eastern Mediterranean fell into their hands, and in 1070, a year before Manzikert, they entered the Holy City, Jerusalem.

These two events shocked both Western and Eastern Europe. Both began to fear that the Turks would slowly dominate the Christian world, making their religion disappear. In addition, numerous rumors began to spread about torture and other horrors being committed against pilgrims in Jerusalem by the Turkish authorities.

The First Crusade was not the first instance of Holy War between Christians and Muslims inspired by the papacy. Pope Alexander II had already preached war against the Muslim infidel on two occasions. The first was in 1061, during the conquest of Sicily by the Normans, and the second in the context of the wars of the Iberian Reconquest, in the Barbastro Crusade of 1064. In both cases, the Pope offered indulgence to the Christians who participated.

In 1074, Pope Gregory VII called upon the milites Christi ("soldiers of Christ") to come to the aid of the Byzantine Empire after its heavy defeat at the Battle of Manzikert., although it was largely ignored and even met with considerable opposition, along with the large number of pilgrims traveling to the Holy Land during the 11th century and to which the conquest of Anatolia had closed land routes to Jerusalem, served to focus much of the Western attention on events in the East.

In 1081, a capable general, Alexios Komnenos, ascended the Byzantine throne, who decided to vigorously confront Turkish expansionism. But he soon realized that he could not do the job alone, so he began rapprochement with the West, despite the fact that the western and eastern branches of Christendom had severed relations in the Great Schism of 1054. Alexios was interested in being able to count with a western mercenary army that, together with the imperial forces, would attack the Turks at their base and send them back to Central Asia. He particularly desired to use Norman soldiers, who had conquered the kingdom of England in 1066 and around the same time had driven the same Byzantines out of southern Italy. Due to these encounters, Alexios knew the power of the Normans. And now he wanted them as allies.

Alejo sent emissaries to speak directly with Pope Urban II, to ask his intercession in the recruitment of mercenaries. The papacy had already shown itself capable of intervening in military affairs when it promulgated the so-called "Truce of God", through which combat was prohibited from Friday at sunset until Monday at dawn, which significantly reduced the contentions between the quarrelsome nobles.. Now was another chance to demonstrate the pope's power over the will of Europe.

In 1095, Urban II convened a council in the city of Plasencia. There he presented the Emperor's proposal, but the conflict of the bishops attending the council, including the pope, with the Holy Roman Emperor, Henry IV (who was supporting an antipope), prevailed over the study of the Constantinople petition. Alejo would have to wait.

- The European society, in its future, had accumulated considerable war potential. Moreover, Islam had been erected in a dangerous and strong enemy. Both were brought together and gave rise to the crusades, projected by Western Christianity to save the eastern Christianity of Muslims. The result, however, was far from the purposes and, in purity, the crusade movement, historically considered, was a debatable failure (though more than a hundred years of trade prove otherwise).

- Steven Runciman sums it up like this:[chuckles]required] When Urbano II predicted his magnificent sermon in Clermont, the Turks were about to threaten the Bosphorus. When Pope Pius II predicted the last crusade, the Turks were crossing the Danube. Rhodes, one of the last fruits of the movement, fell into the power of the Turks in 1523, and Cyprus, ruined by the wars with Egypt and Genoa, and finally annexed to Venice, passed to them in 1570. All that remained for the conquerors of the West was a handful of Greek islands that Venice kept precariously in its power.

- The Turkish advance was contained by the joint effort of Christianity, and by the action of the States to whom it was closer, Venice and the Habsburg Empire, with France, the former protagonist of the holy war, helping the unfaithful in a continuous way.

- There were nine crosses since the centuryXI until XIII.

Consequences

Religious

They were a test of the power of the Latin Church and allowed it to make contact with the Christian communities of the East. However, they provoked a conflict with the Orthodox Church that aggravated the situation opened by the schism of 1054. The Latin conquest of Constantinople provoked the resentment of the Orthodox, to the point that two and a half centuries later, before the Turkish siege of the city, they could say: "the Sultan's turban is preferable to the Pope's tiara." In the kingdoms of the West, the crusade acquired a religious prestige that lasted for a long time, and its proclamation served as the basis for the first religious wars of Christianity, the crusade against the Albigensians, the Reconquest and the Livonian crusade. In relation to the Muslims, the Crusades marked the lowest point in the relations between both Abrahamic religions; Christianity presented the Muslim as an enemy before whom there was no other possibility than to annihilate him (only Francis of Assisi questioned this idea) and Islam stopped respecting Christians as one of the "peoples of the Book", considering them a natural enemy. For their part, the Jews suffered the greatest persecutions up to then in Europe and the crusades marked the beginning of the first pogroms.

Social

The crusades weakened feudal lords; many lost their lives or remained in the East; others became impoverished by the sale of their lands; moreover, the prolonged absence prevented them from monitoring their rights. The kings seized the vacant fiefs and stubbornly reduced the privileges of the lords. For their part, the serfs and vassals achieved their freedom in exchange for wealth. The cities and the bourgeoisie benefited from the profits provided by supplies, the transport of armies and the increase in traffic with the East. The French, the main participants in the crusades, enjoyed an influence in the eastern countries that lasted until contemporary times.

Economics

New crops and manufacturing procedures borrowed from Muslim peoples were introduced to the West. Trade, especially maritime, gained momentum. The ports of Genoa, Venice, Amalfi, Marseille and Barcelona were the most favored.

Cultural

Arabic and Byzantine art and science enhanced Western culture; customs underwent significant changes and the way of life became less harsh.

The Nine Crusades

Between 1096 and 1272, nine crusades took place, with varying results and duration. Even some of them are not recognized by some scholars as crusades, here is included the chronology of each one of them, after a brief summary of each one, and a link to the article that studies them.

| Crusade | Start | It ends. |

|---|---|---|

| First crusade | 1095 | 1099 |

| Second Crusade | 1144 | 1148 |

| Third crusade | 1187 | 1192 |

| Fourth Crusade | 1198 | 1204 |

| Fifth crusade | 1217 | 1222 |

| Sixth crusade | 1228 | 1229 |

| Seventh crusade | 1248 | 1254 |

| Eighth Crusade | 1270 | 1270 |

| Ninth Crusade | 1271 | 1272 |

First Crusade

Gregory VII was one of the popes who most openly supported the crusade against Islam in the Iberian Peninsula and who, in view of the successes achieved, conceived of using it in Asia Minor to protect Byzantium from Turkmen invasions.

His successor, Urbano II, was the one who put it into practice. The formal appeal took place on the penultimate day of the Council of Clermont (France), Tuesday, November 27, 1095. In an extraordinary public session held outside the cathedral, the pope addressed the crowd of religious and lay people gathered to communicate to them very special news. Showcasing his oratorical skills, he expounded the need for Western Christians to engage in a holy war against the Turks, who were inflicting violence on the Christian kingdoms in the East and mistreating pilgrims going to Jerusalem. He promised remission of sins for those who came, a mission that lived up to God's demands and a hopeful alternative to the miserable and sinful earthly life they led. They should be ready to go the following summer and would have divine guidance. The crowd responded passionately with shouts of Deus lo vult ('God wills it!') and a large number of those present knelt before the pope requesting his blessing to join the the sacred campaign. The first crusade (1095-1099) had begun.

The passage of the crusaders through the Kingdom of Hungary

The preaching of Urban II set in motion in the first place a multitude of humble people, led by the preacher Peter of Amiens the Hermit and some French knights. This group formed the so-called popular crusade, crusade of the poor or crusade of Pedro the Hermit. In a disorganized way they headed towards the East, causing massacres of Jews in their path. In March 1096 the armies of King Coloman of Hungary (nephew of the recently deceased King Ladislaus I of Hungary) repelled the French knights of Valter Gauthier who entered Hungarian territory causing numerous robberies and massacres in the vicinity of the city of Zimony. Later the army of Pedro de Amiens would enter, which would be escorted by the Hungarian forces of Coloman. However, after the crusaders from Amiens attacked the escorting soldiers and killed nearly 4,000 Hungarians, King Coloman's armies would maintain a hostile attitude against the crusaders crossing the kingdom towards Byzantium.

Despite the ensuing chaos, Coloman allowed entry to the Crusader armies of Volkmar and Gottschalk, whom he also eventually had to face and defeat near Nitra and Zimony, who like the other groups wreaked untold havoc and murder.. In the particular case of the German priest Gottschalk, he entered Hungarian soil without the king's authorization and established a camp near the settlement of Táplány. Massacring the local population, an enraged Coloman forcibly expelled the invading Germanic soldiers.

Then the Hungarians would stop the forces of Count Emiko (who had already murdered some four thousand Jews on German soil) near the city of Moson. Coloman immediately forbade Emiko's stay in Hungary and was forced to face the Germanic count's siege of the city of Moson, where the Hungarian king was staying. Coloman's forces bravely defended the city and, breaking the siege, succeeded in dispersing the besieger's Crusader forces.

Shortly after, the Hungarian king forced Godfrey of Bouillon to sign a treaty in the abbey of Pannonhalma, where the crusaders promised to pass through Hungarian territory with peaceful behavior. After this, the forces would continue out of the Hungarian territory escorted by the armies of Coloman and would go towards Constantinople. Upon his arrival in Byzantium, the Basileus hastened to send them across the Bosphorus. They carelessly entered Turkish territory, where they were easily annihilated.

The Crusade of the Princes

Much more organized was the so-called crusade of the Princes (usually referred to in historiography as the first crusade) around August 1096, formed by a series of contingents armed mainly from France, the Netherlands and the Norman kingdom of Sicily. These groups were led by second-in-command of the nobility, such as Godofredo de Bouillon, Raymond of Tolosa and Bohemond of Taranto.

During their stay in Constantinople, these chiefs swore to return to the Byzantine Empire those territories lost to the Turks. From Byzantium they headed towards Syria through the Seljuk territory, where they achieved a series of surprising victories. Once in Syria, they laid siege to Antioch, which they conquered after a seven-month siege. However, they did not return it to the Byzantine Empire, but Bohemond retained it for himself, creating the Principality of Antioch.

With this conquest the first crusade ended, and many crusaders returned to their countries. The rest stayed to consolidate possession of the newly conquered territories. Together with the Kingdom of Jerusalem (initially led by Godofredo de Bouillon, who took the title of Defender of the Holy Sepulcher) and the principality of Antioch, the counties of Edessa (present-day Urfa, in Turkey) and Tripoli (in present-day Lebanon) were also created.).

These initial successes were followed by a wave of new fighters who formed the so-called Crusade of 1101. However, this expedition, divided into three groups, was defeated by the Turks when they tried to cross Anatolia. This disaster dampened the crusading spirits for a few years.

Venetian Crusade

The Venetian Crusade of 1122-1124 was an expedition to the Holy Land launched by the Republic of Venice that succeeded in capturing the city of Tyre. It was a major victory at the start of a period when the kingdom of Jerusalem would expand to its greatest extent under King Baldwin II. The Venetians obtained valuable trading concessions in Tyre. Through raids on the territory of the Byzantine Empire, both on the way to the Holy Land and on the return trip, the Venetians forced the Byzantines to confirm, as well as expand, their trading privileges with the empire.

Preparation

Baudwin of Bourg was the nephew of Baldwin I of Jerusalem and Count of Edessa from 1100 to 1118. In 1118 his uncle died and he ascended the throne as Baldwin II of Jerusalem. At the Battle of Ager Sanguinis, fought near Sarmada On June 28, 1119, the forces of Ilghazi, the lord of Mardin inflicted a crushing defeat on the Franks. That same year, Baldwin recovered part of the territory that had been lost as a result of the disaster, but the Franks were seriously weakened. Baldwin asked Pope Callixtus II for help. The pope sent the request to Venice.

The terms of the crusade were agreed upon through negotiations between Baldwin II's envoys and the Doge of Venice. Once the Venetians decided to participate, Pope Callixtus II sent them his papal standard to express his approval. At the First Lateran Council he confirmed that the Venetians enjoyed Crusader privileges, including the remission of their sins.The Church also extended its protection to Crusader families and property.

In 1122, the Doge of Venice, Domenico Michiel, embarked on the maritime crusade. The Venetian fleet of more than 120 ships carrying more than 15,000 men set sail from the Venetian lagoon on August 8, 1122. This seems to have been the first crusade in which the knights took their horses with them. They encircled Corfu, then held by the Byzantine Empire, with which Venice had a dispute over privileges. In 1123, Baldwin II was captured by Balak of Mardin., emir of Aleppo, and was imprisoned in Jarput; Eustace of Grenier assumed the regency of Jerusalem. The Venetians abandoned the siege of Corfu when they received the news and headed for the Holy Land; they reached the Palestinian coast in May 1123.

Second Crusade

Thanks to the division of the Muslim States, the Latin States (or Franks, as they were known by the Arabs), managed to establish themselves and endure. The first two kings of Jerusalem, Baldwin I and Baldwin II, were rulers capable of expanding their kingdom to the entire area between the Mediterranean and the Jordan, and even beyond. They quickly adapted to the changing system of local alliances and came to fight alongside Muslim states against enemies that, in addition to Muslims, included Christian warriors among their ranks.

However, as the spirit of the crusade waned among the Franks, who were increasingly comfortable in their new lifestyle, the spirit of jihad or holy war agitated grew among the Muslims. by preachers against their impious rulers, capable of tolerating the Christian presence in Jerusalem and even siding with their kings. This sentiment was exploited by a series of warlords who managed to unify the different Muslim states and embark on the conquest of the Christian kingdoms.

The first of these was Zengi, governor of Mosul and Aleppo, who in 1144 conquered Edessa, liquidating the first of the Frankish states. In response to this conquest, which revealed the weakness of the Crusader States, Pope Eugene III, through Bernardo, abbot of Clairvaux (famous preacher, author of the Templar rule) preached the second crusade in December 1145..

Unlike the first, the kings of Christendom participated in this one, headed by Louis VII of France (accompanied by his wife, Eleanor of Aquitaine) and by the Germanic emperor Conrad III. Disagreements between the French and the Germans, as well as with the Byzantines, were constant throughout the expedition. When both kings arrived in the Holy Land (separately) they decided that Edessa was an unimportant objective and marched on Jerusalem. From there, to the despair of King Baudouin III, instead of facing Nur al-Din (Zengi's son and successor), they chose to attack Damascus, an independent state and an ally of the King of Jerusalem.

The expedition was a failure, as after only a week of fruitless siege, the Crusader armies withdrew and returned to their countries. With this futile attack they managed to make Damascus fall into the hands of Nur al-Din, who was progressively encircling the Frankish States. Later, Baldwin III's attack on Egypt would lead to the intervention of Nur al-Din on the southern border of the kingdom of Jerusalem, paving the way for the end of the kingdom and the calling of the third crusade.

Third Crusade

Meddling by the Kingdom of Jerusalem in Egypt's decadent Fatimid Caliphate led Sultan Nur al-Din to send his lieutenant Saladin to take charge of the situation. It did not take long for Saladin to become the master of Egypt, although until Nur al-Din's death in 1174 he respected Nur al-Din's sovereignty. But after his death, Saladin proclaimed himself sultan of Egypt (despite the fact that there was an heir to the throne in Nur al-Din, his son, only twelve years old, who died of poisoning) and of Syria, beginning the Ayyubid dynasty. Saladin was a wise man who achieved the union of the Muslim factions, as well as political and military control from Egypt to Syria.

Like Nur al-Din, Saladin was a devout Muslim determined to drive the Crusaders out of the Holy Land. Baldwin IV of Jerusalem was surrounded by a single state and was forced to sign fragile truces trying to delay the inevitable end.[citation needed]

After the death of King Baldwin IV of Jerusalem, the state divided into different factions, pacifist or warlike, and he went on to become king, due to the marriage he had with the sister of the deceased patriarch, the general in chief of the united army of Jerusalem: Guido de Lusignan. He himself supported an aggressive policy and non-negotiation with the Saracens and advocated their submission and defeat in combat, something that his detractors opposed given the numerical inferiority that the Christians had before Saladin's troops. The religious radicalism and the support for the most radical arm of the Templar order in its attacks on various Saracen towns and structures would lead to a final confrontation between Guy de Lusignan and Saladin himself. In fact, Guy de Lusignan is blamed for the defeat and loss of Jerusalem because of his obsession with confronting Saladin's army and his lack of vision for the protection of the city and its inhabitants.

Reinald of Châtillon was a knighted bandit who did not consider himself bound by the truces signed. He looted caravans and even organized pirate expeditions to attack pilgrim ships going to Mecca, a very important city for Muslims. The final attack was against a caravan in which Saladin's sister was traveling, who swore to kill him with her own hands.

War declared, the bulk of the Crusader army, along with the Templars and Hospitallers, faced Saladin's troops at the Horns of Hattin on July 4, 1187. The Christian armies were defeated, leaving the kingdom defenseless and losing one of the fragments of the Vera Cruz.

Saladin killed Reinald of Châtillon with his bare hands. Some of the captured Knights Templar and Hospitallers were also executed. Saladin proceeded to occupy most of the kingdom, except for the coastal places, supplied from the sea, and in October of the same year he conquered Jerusalem. Compared to the takeover of 1099, this was almost bloodless, although its inhabitants had to pay a considerable ransom and some were enslaved. The kingdom of Jerusalem had disappeared.

The capture of Jerusalem shocked Europe and Pope Gregory VIII called a new crusade in 1189. Some of the most important kings of Christendom participated in it: Ricardo Corazón de León (son of Enrique II and Eleanor of Aquitaine), Felipe II Augusto of France and the Emperor Federico I Barbarossa (nephew of Conrad III). The latter, in command of the most powerful group, followed the land route, in which he suffered some casualties. Near Syria, however, the emperor drowned while bathing in the Salef River (in present-day Turkey) and his army no longer continued on to Palestine.

During his stay in the Kingdom of Hungary, Barbarossa had asked Prince Géza, brother of King Bela III of Hungary, to join the crusading forces, thus, an army of two thousand Hungarian soldiers left for the Germans. Although after the war conflicts the Hungarian king would have called back his forces, his younger brother, Géza, remained in Constantinople and married a Byzantine noblewoman, since he did not have good relations with Béla III.

The English and French armies arrived by sea route. His first (and only) success was the capture of Acre on July 13, 1191, after which Richard massacred several thousand prisoners. This slaughter militarily gave him oxygen to continue south to his final goal: Jerusalem, and also earned him the name by which he would be known in history, Lionheart.

Philip II Augustus was concerned about the problems in his country and annoyed by rivalries with Richard the Lionheart, so he returned to France, leaving Richard in command of the crusade. He reached the vicinity of Jerusalem, but instead of attacking he preferred to sign a truce with Saladin, fearing that his decimated army of 12,000 men would not be able to hold the siege of Jerusalem. Thinking of an upcoming crusade and not risking a military defeat that would not give the Christians the possibility of later control of the Holy City, they agreed with Saladin himself, who was also tired and decimated, the truce that allowed free access to unarmed pilgrims to the Holy City.

Saladin died six months later. Richard died in 1199 from an arrow wound during a campaign of conquest in France. In this way, the third crusade ended with a new failure for both sides, leaving the Frankish states without hope. It was a matter of time before the narrow coastal strip they controlled disappeared. However, they held out for another century.

Fourth Crusade

After the truce signed in the Third Crusade and the death of Saladin in 1193, there followed a few years of relative peace, in which the Frankish states of the littoral became little more than Italian trading colonies. In 1199, Pope Innocent III decided to call a new Crusade to alleviate the situation of the Crusader States. This fourth crusade should not include kings and be directed against Egypt, considered the weakest point of the Muslim states.

Since the land route was no longer possible, the crusaders had to take the sea route, so they concentrated on Venice. Doge Enrico Dandolo joined forces with the head of the expedition, Boniface of Montferrat, and with a Byzantine usurper, Alexios IV Angelo, to change the fate of the crusade and direct it against Constantinople, since all three were interested in the deposition of the basileus of the moment, Alejo III Angelo.

Initially, the crusaders were used to fight the Hungarians in Zadar, for which they were excommunicated by the pope. From there they went to Byzantium, where they managed to install Alexios IV as basileus in 1203. However, the new basileus could not keep the promises made to the crusaders, which caused all kinds of disturbances. He was deposed by the Byzantines themselves, who crowned Alexios V Ducas. This led to the definitive intervention of the crusaders, who conquered the city on April 12, 1204. The next morning, they were informed that they had three days to dedicate themselves to looting and they exercised their prerogative in a way never known before. The looting of the city was terrible. Mansions, palaces, churches, libraries and the Basilica of Saint Sophia itself were looted and destroyed. Men, children and women were outraged and murdered to such an extent that the historian Nicetas felt that the Saracens would have been more lenient. Western Europe received an unprecedented barrage of works of art and relics from this looting.

The Byzantine Empire was dismembered into a series of states, some Latin and some Greek. The Crusaders established the so-called Latin Empire, organized feudally and with very weak authority over most of the territories it supposedly controlled (and zero over the Greek states of Nicaea, Trebizond, and Epirus). The so-called Empire of Nicea, one of the successor Greek states that were born from the conquest of Constantinople, would manage to retake the city and restore the Byzantine Empire in July 1261. However, the damage left by the crusade was irreversible. The Eastern Roman Empire continued to exist for another two centuries, but as a mere shadow of its former self.

The Fourth Crusade dealt a double blow to the Frankish states of Palestine. On the one hand, it deprived them of military reinforcements. On the other hand, by creating a pole of attraction in Constantinople for the Latin knights, it caused the emigration of many who were in the Holy Land towards the Latin Empire, leaving the Frankish States.

The Minor Crusades

After the failure of the fourth, the crusader spirit had almost completely died down, despite the interest of some popes and kings to revive it. If the Frankish states survived until 1291, it was because of the intervention of the Mongols who, by ending the Abbasid Caliphate in 1258 and conquering the Middle East region, gave the Latins a break, since the Mongols were not hostile to Christianity.

The conviction that the repeated failures were due to the lack of innocence of the crusaders, led to the conclusion that only the pure could reconquer Jerusalem. In 1212, a 12-year-old preacher organized the so-called children's crusade, in which thousands of children and young people[citation needed] toured France and they embarked in their ports to go to liberate the Holy Land. They were captured by unscrupulous captains and sold into slavery. Only a few managed to return after the years.

Fifth Crusade

The fifth crusade was proclaimed by Innocent III in 1213 and he set out in 1218 under the auspices of Honorius III, joining the crusader king Andrew II of Hungary, who led eastward the largest army in the entire history of the crusades. Like the fourth crusade, it was aimed at conquering Egypt. After the initial success of the conquest of Damietta at the mouth of the Nile, which ensured the survival of the Frankish states, the crusaders became overpowered by ambition and tried to attack Cairo, failing and having to abandon even what they had conquered, in 1221.

Sixth Crusade

The organization of the Sixth Crusade was somewhat audacious. The Pope had ordered the Hohenstaufen Emperor Frederick II to go on crusades as a penance. The emperor had agreed, but he had been delaying the departure, which earned him excommunication. Finally, Frederick II (who had claims of his own to the throne of Jerusalem) departed in 1228 without the pope's permission. Surprisingly, the emperor managed to retake Jerusalem through a diplomatic agreement. He proclaimed himself king of Jerusalem in 1229 and also obtained Bethlehem and Nazareth.

Seventh Crusade

In 1244 Jerusalem fell again (this time permanently), prompting the devout King Louis IX of France (Saint Louis) to organize a new crusade, the Seventh. As in V, he went against Damietta, but was defeated and taken prisoner in El Mansura (Egypt) with his entire army.

Eighth Crusade

25 years later; Louis IX of France once again organized another crusade, the eighth (1269), the plan being to land in Tunis and move overland to Egypt; this was proposed by Carlos de Anjou king of Naples, with the intention of gathering the troops in the prosperous commercial region of Tunisia where funds for the invasion would be obtained. They disembarked unaware that there was a dysentery epidemic in the region, Luis was infected and died a few days later. (1270).

Ninth Crusade

The Ninth Crusade is sometimes considered to be part of the Eighth. Prince Edward of England, later Edward I, joined Louis IX of France's crusade against Tunisia, but arrived at the French camp after the king's death. After spending the winter in Sicily, he decided to continue with the crusade and led his followers, between 1,000 and 2,000, to Acre, where he arrived on May 9, 1271. He was also accompanied by a small detachment of Bretons and another of Flemings, led by the Bishop of Liège, who would abandon the campaign in winter before the news of his election as the new pope, Gregory X. Eduardo and his army were limited to being a guerrilla that after a year ended with the signing of a truce on May 22, 1272 in Caesarea. However, it was known to all that Edward intended to return in the future to lead a larger and more organized crusade, so they sent a Hashshashin agent who stabbed the prince with a poisoned dagger on June 16, 1272. The wound it was not fatal, but Edward was ill for several months, until his health allowed him to leave for England on 22 September 1272.

Although Edward and some popes tried to preach new crusades, they were no longer organized and, in May 1291, after the fall of Acre, the crusaders evacuated their last possessions in Tyre, Sidon and Beirut. After all, the only relevant triumph of Christianity during the two centuries of more than eight crusades was the capture of Jerusalem by Godfrey de Bouillon in the first crusade in the year 1099, which, despite the massacres of Saracens and Jews (men, women and children), managed to sustain the Holy City for many years, and met the objectives initially set by the defenders of the idea of reconquering the so-called holy land for the Christians of Europe.

Wars classified as crusades on European soil

The Baltic Crusades

They were a series of campaigns undertaken by Christian leaders in Germany, Denmark, and Sweden, between the 12th and XVI, with the main objective of subjugating and converting the pagan peoples of the Baltic basin and against other Christian peoples considered equally infidels. One of the main actors in these campaigns was the Teutonic Order, which had previously been created in Palestine.

The crusades in the Baltic respond to a social movement developed in the German Empire in the middle of the XII century. This movement is known as Drang nach Osten.

Crusade against the Albigensians

In 1209 Pope Innocent III proclaimed the Albigensian Crusade in order to eliminate the heresy of the Cathars and eradicate them from southern France.

Aragonese Crusade

The crusade against the Crown of Aragon was declared by Pope Martin IV against the King of Aragon Pedro III the Great, in 1284 and 1285.

Crusades in the Iberian Reconquest

Some moments of the final period of the Reconquista were classified by the Pope as a crusade, given its condition of confrontation between Christian kingdoms and Islamic kingdoms. However, the motivation for the search for such a denomination was not so much the interest in achieving the presence of European nobles on the other side of the Pyrenees (very unimportant), as the interest in obtaining some type of fiscal rights for the monarchy (on the income from the clergy or as Bull of Crusade). The main occasions were the battle of Las Navas de Tolosa (1212), in which almost all the peninsular Christian kings were present, and the war in Granada (1482-1492).

Sigismund of Hungary's Crusade

This crusade is considered the last of a pan-European magnitude to be waged against the Ottoman Empire. In 1396, King Sigismund of Hungary organized a crusade to besiege the city of Nicopolis, then under Ottoman Turkish control. The armies of Prince Mircea I of Wallachia and Duke John I of Burgundy advanced under the leadership of King Sigismund determined to expel the Ottomans from the Balkan territories.

The defense of the city proved impossible to defeat, and the lack of siege engines by the allied forces resulted in a severe defeat. The Turkish victory at the siege of Nicopolis threatened the Central European nations and consolidated Ottoman power on the border with the kingdom of Hungary.

Crusade of John Hunyadi, Regent of Hungary

The Turkish advance on the Kingdom of Hungary was imminent. The defeat of the Crusader armies of King Sigismund of Hungary at the Battle of Nicopolis in 1396 and the defeat of the Hungarian armies at the Battle of Varna in 1444 in which King Wladislaus I of Hungary was killed gave strength to the Ottoman Empire. In this way, he continued his march in the direction of Belgrade, a Serbian city bordering the Hungarian kingdom in 1456. Immediately, the Hungarian regent Juan Hunyadi (who after the death of the monarch led the kingdom while the crown prince Ladislaus the Posthumous fulfilled the majority of age to ascend to the throne) responding to the call of Pope Calixto III and assisted by Saint John Capistrano, they organized a Hungarian crusader army that faced the invading Ottomans. The battle ended in total victory for the Hungarian regent and the Turkish threat was halted for almost another century. Before the victory of Belgrade of the Hungarians, the Pope ordered that the bells of noon in the churches of the whole world sounded in honor of such an event.

Contenido relacionado

Alfonso VI

1931

Newfoundland and labrador