Crazy scientific

A ''mad scientist'' is a type character (stereotype) in popular narrative that can be evil or benign, but is always clueless Psychotic, eccentric or simply clumsy, the mad scientist often works with completely fictitious technology, with the aim of facilitating his more or less perverse plans. Alternatively, he does not notice the immorality that derives from the arrogance of "playing God."

Although the mad scientist was initially depicted as an antagonist in works of fiction, due to the recent spread of geek culture, modern depictions of mad scientists are often satirical and humorous, instead of criticism. Some are even protagonists of fiction, like Dexter in the cartoon series Dexter's Laboratory.

Distinctive characteristics

Mad scientists are generally characterized by obsessive behavior and the use of extremely dangerous or very unorthodox methods. They are often motivated by revenge, attempting to avenge mockery and ridicule, real or imagined, as a result of their strange and unorthodox investigations.

Their laboratories are often teeming with Tesla coils, Van de Graaff generators, perpetual motion generators and other strange, outlandish-looking electronic mechanisms, or filled with test tubes and complicated distillation apparatus, containing strange colored liquids whose usefulness it is unknown.

Other features include:

- Pursue scientific research at all costs without worrying about its destructive or even ethical consequences, such as violating the Nuremberg Code.

- Self-experience.

- To believe a divinity, playing with Nature.

- The lack of normal social relations, often to the point of being “hermittans”

- Permanently neglected appearance, sometimes presence of physical deformities, and dememocrated in performing basic and uninteresting tasks because, as good sages, they are very distracted for it.

- In English-language movies or cartoons, speaking with a German or Eastern European accent. This is largely due to massive emigration to the United States of European scientists in two waves: the first, before World War II, when they escaped from Nazism, and the second after the war, either when they escaped from the Soviet Union, or were former Nazi employees who fled to the United States (see Operation Paperclip). In some Spanish doublings they also appear imitating those accents.

- In the villains, the malevolent laughter, especially when their experiments reach climax.

- The possession of some academic qualifications, usually from Doctor or Professor.

- They are, almost invariably, white men.

- See differences with evil Genius

It should be noted that most of these traits are nothing more than exaggerations of typical stereotypes of normal scientist behavior: scientists are often obsessive about their own work, disinterested in social considerations that interfere with their goals, continually adopting a 'careless' worldview, etc.

Perhaps it is also interesting to note that the general public usually has contact with active scientists during their university years. In this very stratified environment, it is not unusual to have an impression of selfishness in teachers, of obsession with their personal research or of indifference.

As a narrative archetype, the mad scientist can be seen as the representation of the fear of the unknown, of the consequences that result when humanity dares to meddle in "things that are better left alone." Similarly, the tendency of mad scientists to play God may be an extension of the differences between religion and science, as exemplified by arguments about the theory of evolution, one of the favorite topics of mad scientists, which often They often create fantastic beasts and monsters in their laboratories. When Frankenstein's monster came to life, its creator, Victor Frankenstein exclaimed: “Now I know how God feels!” This phrase was considered controversial and was censored in the 1931 film version.

History

Precursors

Since ancient times, the popular imagination revolved around archetypal figures who possessed esoteric knowledge. Shamans and healers received special treatment, because they were afraid of their supposed abilities to conjure beasts and create demons. They shared many of the characteristics that were later transferred to mad scientists, such as their eccentric behavior, their status as hermits, and their ability to create life.

As a consequence of the arrival of Christianity, animistic beliefs weakened or disappeared in Western culture, and a new discipline was born that set out to manipulate nature: alchemy. Alchemists were known for their extravagant behavior, often caused by mercury poisoning, in the case of Isaac Newton for example. Their common ambition was to create the homunculus, an artificial human. Alchemy declined with the advent of modern science and the scientific method during the Enlightenment.

Birth of science and science fiction

Since the 19th century, imaginary representations of science have oscillated between notions of science as the savior of society and of its ruin. Consequently, the representations of the scientists in the narrative varied between the virtuous and the degenerate, between the sane and the mad. In the 20th century, optimism for progress was the most common attitude toward science, but latent anxieties about revealing "the secrets of nature" would come to the surface following the growing role of science in matters of war.

The mad scientist par excellence in the narrative was Dr. Victor Frankenstein, creator of the so-called Frankenstein monster. The creature, which made its first appearance in 1818 in the novel Frankenstein or The Modern Prometheus by Mary Shelley. Although Victor von Frankenstein was a positive character, the critical element of carrying out forbidden experiments that cross boundaries that should not be “crossed” is present in Shelley's novel. Furthermore, Frankenstein was educated as an alchemist and as a modern scientist, thus making him a “bridge” between two eras of an evolving archetype. His monster is, essentially, the homunculus of a new form of literature, science fiction.

The 1927 film Metropolis, directed by Austrian expressionist director Fritz Lang, brought the archetype of the mad scientist to the cinema with the character of Rotwang, the evil genius whose machines bring the dystopian city to life which gives the title to the film. Rotwang's laboratory influenced many later films with its luminous arcs, boiling apparatus, and highly complicated collection of gauges and buttons. Played by actor Rudolf Klein-Rogge, Rotwang is the prototypical mad scientist in conflict with himself; Although he is the owner of an almost mystical scientific power, he is a slave to his desire for power and revenge. Rotwang's appearance was also influenced by him: messy hair, demonic eyes and his fascist laboratory quickly became common characteristics of mad scientists. Even his mechanical right hand became a mark of the mad scientist's power, echoed inDr. Strangeloveby Stanley Kubrick.

Nevertheless, the essentially benign and progressive impression of science in the public mind continued unaltered, exemplified by the optimistic exhibition 'Century of Progress', in Chicago in 1933, and in the world exhibition 'World of Tomorrow', New York in 1939. After World War I, public attitudes began to change, if only slightly, when chemical warfare and Planes became the most fearsome weapons of the time. For example, of all the science fiction produced before 1914 that dealt with the end of the world, two-thirds had natural causes, such as an asteroid collision, and the other third was due to an end caused by humans, such as the end of the world. which half was accidental and the other half voluntary. After 1914, the idea of a human being eliminating the rest of humanity became a more imaginable, although still unrealizable, fantasy, and the proportion rose to two-thirds of all scenarios, which foresaw the end of the world as products of negligence. or bad human intention. Although still dominated by optimistic feelings, they planted the seeds of anxiety.

The most common ally of the mad scientists of this era was electricity, seen by the ignorant public as a semi-mystical force with chaotic and unpredictable properties.

After 1945

Mad scientists had their heyday in the popular culture of the post-World War II period. The sadistic medical experiments of the Nazis and the invention of the atomic bomb gave rise to real fears that science and technology were out of control.

Scientific and technological development during the Cold War, with its increasing threats of unparalleled destruction, did not help to reduce this impression. Mad scientists frequently appeared in science fiction and films of the time. The movieDr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, in which Peter Sellers plays Dr. Strangelove, is perhaps the latest expression of this fear of the power of science, or the misuse of such power.

In more recent years, the mad scientist, seen as a solitary researcher of the unknown and forbidden, tends to be replaced by mad entrepreneurs who plan to profit by defying the laws of nature and humanity, regardless of the sufferings of others; These characters hire scientists and specialists to achieve their twisted dreams.

Mad scientists' techniques changed after Hiroshima. Electricity was replaced by radiation, which became the new means of creating, enlarging or deforming life (e.g. Godzilla). As the public became more educated, genetic engineering and artificial intelligence came onto the scene.

Mad scientists and the relationship between man and technology in general are analyzed by the webcomic A Miracle of Science. In the series, the mad scientists are actually victims of Science-Related Memetic Disorder, a contagious memetic disease that causes obsessive behavior focused on some forms of technology.

Consequences of the stereotype

Various research has indicated that young people, when describing a scientist, tend to consider this stereotype as correct and close to reality. This has as a consequence, according to some research groups, a process of disidentification with science and with the possibilities of learning it in some groups of students. For these investigations, the "Draw-a-Scientist Test" is usually used.; (DAST, Draw a Scientist Test), published by D.W. Chambers in 1983, collecting drawings of scientists made by children between 1966 and 1977. In his descriptions, male scientists always appear, isolated, crazy, poorly dressed, etc.

As this is a biased vision, there have been various proposals of educational interest to bring young people closer to models closer to current reality, composed of specialists of both sexes, in constant connection with the world and making contributions to collective construction to society. These initiatives have attempted to show a more humanized vision of science and its work. Within the lines of intervention for the humanized vision of science, the assessment of current scientists and their work stands out, as well as other aspects of their lives that can bring them closer to the daily lives of students.

Real prototypes

Scientists in literature and the popular imagination have better defined our "mad scientist" more than real scientists have done, because that is their function, to reflect our prejudices. "Popular beliefs and behaviors are more influenced by images than by demonstrable facts." (Roslynn Doris Haynes, 1994).

Some real scientists, not necessarily crazy, whose personality, and sometimes appearance, have contributed to the stereotype have been:

- Jeremy Bentham, a British philosopher who became mummified.

- Wernher von Braun, developer of missile technology in Germany and the United States.

- Gerald Bull, engineer.

- Horace Donisthorpe, mirmecologist.

- Thomas Alva Edison, "The Wizard of Menlo Park," inventor.

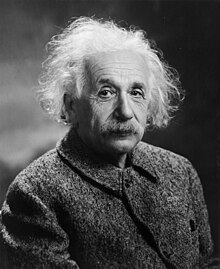

- Albert Einstein, physicist, whose hairstyle is commonly attached to the mad or brilliant scientist.

- Paul Erdős, Hungarian, one of the most prolific and eccentric mathematicians in history.

- Philo Farnsworth, inventor of television and the first nuclear fusion mechanism.

- Francis Galton, a British scientist who developed statistics and eugenics.

- Dr. Shirō Ishii, Lt. General of Unit 731 of the Japanese imperial army.

- Dr. Carl Gustav Jung, Swiss Psychoanalyst who combined psychological science with esoteric concepts.

- Trofim Lysenko, a Soviet biologist who theorized Russian genetics.

- Dr. Sigmund Freud, father of psychoanalysis, based all his theories on speaking morbidly of sex.

- Stanley Milgram, pioneer psychologist of studies on obedience.

- Harry Harlow, a psychologist who wanted to study love for his deprivation.

- Oliver Heaviside, British scientist who replaced his furniture with large granite blocks.

- Herman Kahn, a futurologist who articulated the policy of mutual destruction assured.

- Dr. Josef Mengele, Nazi physician, the "Angel of Death" of Auschwitz.

- Professor Julius Sumner Miller.

- Patrick Moore, British astronomer.

- Jack Parsons, missile researcher.

- Ivan Petrovich Pavlov, physiologist, for his studies on conditional reflex.

- Edward Teller, a nuclear physicist who worked on the development of the hydrogen bomb.

- Nikola Tesla, physicist, mathematician, inventor and mechanical and electrical engineer.

- B. F. Skinner, conductist and utopian.

- John von Neumann, mathematician.

- Auguste Piccard, Swiss inventor and explorer, creator of the Trieste smoothie.

- Edward A. Murphy Jr., American aerospace engineer, famous and remembered for stating the comic " Murphy Law," which says "Everything that can go wrong will go wrong."

- Grigori Perelman, a Russian mathematician who rejected the Fields Medal and the $1 million prize awarded by the Clay Institute of Mathematics for its resolution of the Poincaré Conjecture.

In fiction

Some scientists

[ quote required

- High Evolutionary (Marvel Comics)

- Dr. Emmett Brown (Back to the Future)

- Dr. Fausto

- Griffin (The Invisible Man)

- John Hammond (Jurassic Park)

- Dr. Albert W. Wily (Mega Man, the greatest representative of the "mad scientist" in the video game universe.)

- Arnim Zola (Marvel Comics)

- Erik Selvig (Marvel Film Unit)

- Dexter

- Warren Vidic (Assassin's Creed)

- Rick Sánchez (Rick and Morty)

- N.Brio (Crash Bandicoot)

- N.Gin (Crash Bandicoot)

- Doctor Poison (DC Comics)

- Doctor Neo Cortex (Crash Bandicoot)

- Victor Frankenstein

- Doctor Octopus (Marvel Comics)

- Scarecrow

- Dr. Jumba Jookiba (Lilo & Stitch)

- Dr. Heinz Doofenshmirtz (Phineas and Ferb)

- Doctor Mortis

- Karl Malus (Marvel Comics)

- Doctor Doom (Marvel Comics)

- Mr. Crocket (The Magic Godfathers)

- M.O.D.O.K. (Marvel Comics

- Doc Emmett Brown (back/back to the future)

- The Grandfather (The Monster Family)

- Professor Hubert Farnsworth (Futurama)

- Professor Neurus

- Drakken (Kim Possible)

- Kang the Conqueror (Marvel Comics)

- Ichirō Mihara (Angelic Layer)

- Professor Bacterio

- Ian Malcom (Jurassic Park)

- Mayuri Kurotsuchi (Bleach)

- Doctor Sivana DC Comics

- Professor Frink (The Simpsons)

- Leader (Marvel Comics

- Dr. Stein (Soul Eater)

- Rintarō Okabe (Steins;Gate)

- Professor Finbarr Calamitus (Jimmy Neutron)

- Dr. Nefario (Despicable Me)

- Walter Bishop (Fringe)

- Megaly (Megaly)

- Professor Tomoe (Sailor Moon)

- GLaDOS (Portal)

- Kyōma Hōōin (Steins; Gate)

- Flint Lockwood and Chester V (Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs)

- Dr. Zomboss (Plants VS. Zombies)

- Dr. Eggman (Sonic the Hedgehog)

- Dr. Alphonse Mephisto (South park)

- Hiedra Venenosa (DC Comics)

- Uncle Lucas.

- Gyro Gearloose Ciro Peraloca in Hispanic America. Although not necessarily crazy, this Disney character invents weird things.

- Professor Tornasol (Tintiny)

- Dr. Mordin Solus (Mass Effect)

- Mr. Freeze (DC Comics)

- The Professor (The Felix Cat)

- Singed the crazy chemist (League of Legends)

- Desty Nova (GUNNM)

- Beakman

- Wallace Breen (Half-Life 2)

- Dr. Frappe (Dragon Ball)

- Dr. Uirō (Dragon Ball Z)

- Dr. Brief (Dragon Ball Z)

- Dr. Gero (Dragon Ball Z)

- Dr. Myu (Dragon Ball GT)

- Lisa Loud (The Loud House)

Anecdotal

An investigation of 1,000 horror films distributed in the United Kingdom between 1930 and 1980 revealed that mad scientists or their creations have been the villains in 30% of the films; that scientific research has produced 39% of the threats and that, on the other hand, scientists have been the heroes of only eleven films.

Contenido relacionado

Evolutionary strategy

Periodicals

Imagine