Counterpoint

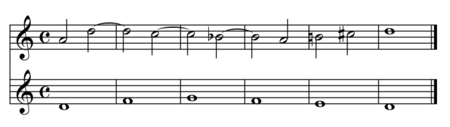

It is an example of 4 voice counterpoint polyphony. The two voices (melodies) in each staff can be distinguished by the direction of the plications of the figures.

The counterpoint (from the Latin punctus contra punctum, «note against note») is a technique of improvisation and musical composition that evaluates the relationship between two or more voices independent (polyphony) in order to obtain a certain harmonic balance. Almost all of the music composed in the West is the result of some contrapuntal process. This practice, which arose in the 14th century, reached a high degree of development in the Renaissance and the period of common practice, especially in the music of the Baroque, and has been maintained to this day.

General principles

In its most general aspect, counterpoint involves the creation of musical lines that move independently of one another but are harmoniously related to one another. In every age, contrapuntal organized music writing has been subject to rules, sometimes strict ones. By definition, chords are produced when several notes are played at the same time. However, the vertical harmonic features are considered secondary and incidental when the counterpoint is the predominant textural element. Counterpoint focuses on melodic interaction and only secondarily on the harmonies produced by that interaction. In the words of John Rahn:

It's hard to write a beautiful song. It is more difficult to write several beautiful songs individually than, when they sing at the same time, they sound even more beautifully polyphonic. The internal structures that create each of the voices separately must contribute to the emerging structure of the polyphony, which in turn must strengthen and develop the structures of the individual voices. The way it takes place in detail is the counterpoint.

Voices, accents, movements and gait rules

The most common in the history of music is the composition for four voices: bass, tenor, contralto and soprano; both for choral composition and for chamber music, especially in string quartet, the art of counterpoint is used for the composition with a different number of voices, following rules that pretend to maintain the independence of the voices while ensuring that the musical composition is harmonious.

The basic technique of counterpoint sets rules for the consonance of the intervals of the accented beats, leaving more freedom for the evolution of the lines between the accents. There are also rules for the treatment of dissonances.

For example, with only two voices, there are three possibilities for the movement of the voices: direct movement, in which the voices rise and fall together (parallel), which reduces the independence of the voices; oblique movement, in which one of the voices does not move while the other rises and falls; and, finally, the opposite movement, in which one voice goes up while the other goes down and is the one that most increases the independence of the melodic lines. The composer must take care that in the accented times the desirable consonance is achieved.

Obviously, as the number of voices increases, the typology of possible movements increases. Contrapuntal methods usually start with two-voice composition and end with more complex compositions, with a greater number of voices. The rules of march of counterpoint seek to provide harmony to the polyphonic composition resulting from the movements of the voices without losing its independence. The rules provide favorable marches and avoid unfavorable marches, which are considered composition errors. Examples of forbidden marches —because they are rude or because they excessively reduce the independence of the voices, unbalancing the musical composition— are: open parallel marches of firsts, fifths or eighths or hidden marches, in which imperfect and perfect consonances alternate

Counterpoint and harmony

Contrapuntal music writing and harmonic music writing have a different emphasis. Counterpoint focuses on the horizontal or linear development of music, while harmony is primarily concerned with intervals, or the vertical relationships between musical notes. Counterpoint and harmony are functionally inseparable since both complement each other, as elements of the same musical system. It is impossible to write simultaneous lines without harmony, and it is impossible to write harmony without linear activity. That is to say, the melodic voices have a horizontal dimension, but when they sound simultaneously they also have a vertical harmonic dimension.

The composer who ignores one aspect in favor of the other must face the fact that the listener cannot simply turn harmonic or linear hearing off at will. Thus, the composer runs the risk of unintentionally creating annoying distractions. Often regarded as the deepest synthesis of two dimensions ever achieved, Johann Sebastian Bach's counterpoint is extremely rich harmonically and always clear tonal directionality, while the individual lines remain mesmerizing.

Both dimensions are conveniently organized according to consonance.

- Consonant intervals are pleasant in the ear. The perfect consonance provides the highest fusion rate intervals. These are the unison, the fourth (and its investment), the fifth and the eighth. However, the fourth was considered to be perfectly consistent with the passage of time. The imperfect consonance, which provides a pleasant sound amplitude, is provided by both the larger and smaller third and sixth intervals (and in some contexts also the fair quarter).

- Dissonances are tensioning, unstable since they generate friction in the ear by the harmonics of the chord that is built. These intervals are the second and seventh as well as harmonic variations of increase and decrease. For example, the fifth diminished or tritonous.

Counterpoint and polyphony

The difference between polyphony and counterpoint is that polyphony is the object treated by counterpoint techniques; that is, an element itself and not the set of techniques that allow it to be manipulated. The counterpoint makes it possible to make the music more lively and varied, modifying the texture of the voices due to variabilities in their treatment, such as the agreement or disagreement between them. The texture is modified by altering the rhythm of the musical notes, as well as the directionality in the movement of the phrases, the dissonances or the accents. Concordant music is reduced to the exposition of several successive chords, and in itself, it already has a certain factor, albeit a minimal one, of counterpoint, since despite the concordance of each one of the voices, it is subject to planned movements and aware of them.

Contrapuntal art was created as a way of giving greater compositional freedom through the use of strange notes and dissonances, which give the possibility that tension and its resolution are musical characteristics present throughout the course of a musical work, which would allow certain artistic margin of maneuver without disturbing the normal development of the music.

Monophony, on the other hand, cannot have contrapuntal features, since for this a minimum of two voices are necessary that can interact in some way with each other.

Historical development

Counterpoint has been an essential part of Western music since the Middle Ages. It developed strongly during the Renaissance, dominating compositional activity for much of the Baroque, Classicism, and Romanticism, although its relative importance declined throughout this period in practice as new compositional techniques were developed. In a broad sense, harmony later became the predominant organizing principle in musical composition.

- Renaissance counterpoint

In the Renaissance (16th century) the work of Palestrina and Orlando di Lasso can be highlighted. Palestrina is considered a top composer of the Renaissance and possibly the first great master of counterpoint.

- Baroque counterpoint

It is considered that the contrapuntal technique reached its zenith at the end of the Baroque, with its greatest exponents being Georg Friedrich Handel and Johann Sebastian Bach (17th-18th centuries). His most outstanding compositions in this field are The Art of the Fugue , The Well-Tempered Clavier and the Musical Offering . Contrapuntal influence can also be highlighted in some of his orchestral and choral compositions, such as the St. Matthew Passion .

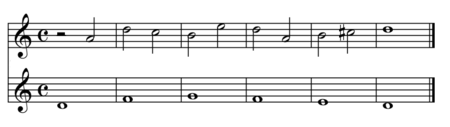

- Contrapoint illustrated

Mozart (18th century) also used counterpoint in much of his work, and especially under a very marked Bachian influence during the second half of his life. Examples of a clearly contrapuntal nature are his string quartets, highlighting the Haydian quartets that he composed between 1782 and 1785. Other classical composers also used counterpoint such as Haydn or Beethoven with their string quartets and their evolved Grosse Fuge, op. 133.

- Romantic counterpoint

It is also said that when the German composer Johannes Brahms got bored, he practiced counterpoint. Brahms used the fugue extensively, such as in his Deutsches Requiem.[citation needed]

- Contemporary counterpoint

In general, throughout the history of music, the term Counterpoint is usually understood as a superposition of simultaneous melodic processes. However, this idea is accompanied by another of equal importance: the control of the relationships between the overlapping points of both melodic processes. In Renaissance music, for example, a dissonant relationship between two voices was expected to resolve its tension towards a consonant interval.

From musical Impressionism, and specifically from Debussy's music influenced by knowledge of Southeast Asian music from the Universal Exhibition of 1880, a new type of Counterpoint emerges —if it can be called that — in which the relationship between the different melodic processes is free —not being based on the concepts of consonance and dissonance of the previous counterpoint—. This is the basis of the so-called "Dissonant Counterpoint" characteristic of much music of the 20th century.

In contemporary history (19th-20th centuries) we can cite some examples such as the Contrapuntal Fantasy BV 256 by Busoni or the Opus clavicembalisticum from Sorabji. The use of counterpoint continues to this day, with special emphasis on jazz.

Species of counterpoint

In general, types of counterpoint offer less freedom for the composer than other types of counterpoint, which is why it is known as rigorous counterpoint or strict. Counterpoint species have been developed as a pedagogical tool, in which a student progresses through several "species" of increasing complexity, with a very simple, unchanging part known as the cantus firmus (In Latin it means "fixed melody"). The student gradually acquires the ability to write free counterpoint, which is the least rigorously limited counterpoint, usually without cantus firmus, according to the rules of the day.

The idea dates back to 1532, when Giovanni Maria Lanfranco described a similar concept in his work Scintille di musica (Brescia, 1533). The Venetian music theorist of the 16th century Zarlino developed this idea in his influential Le institutioni harmoniche. And it was first presented in codified form in 1619 by Ludovico Zacconi in his Prattica di Musica. Zacconi, unlike later theorists, included some additional contrapuntal techniques as species, for example invertible counterpoint. The most famous pedagogue who used the term and who made it famous was Johann Joseph Fux. In 1725 he published Gradus ad Parnassum ( Steps to Parnassus ), a work to aid in the teaching of counterpoint composition to students. Specifically, he focused on the contrapuntal style practiced by Palestrina at the end of the XVI century as the main technique. As the basis for his simplified and often overly restrictive codification of Palestrina's practice (see "General Notes" below), Fux described five species:

- Note against note;

- Two notes against one;

- Four (extended by others to include three or six, etc.) notes against one;

- Disqualified notes against each other (such as suspensions);

- All the first four species together, as counterpoint flower.

A succession of later theorists imitated Fux's original work very closely, but often with some small and idiosyncratic rule modifications. A good example is Luigi Cherubini.

The contributions of Carl Schachter are interesting, from a Schenkerian approach. For this author, the species of counterpoint, which he calls "simple counterpoint", are the basis of the composition, where we find the "elaborated counterpoint". In post-Renaissance composition —according to this author—, the rules and, above all, the procedures of simple or strict counterpoint were not abandoned in favor of the rules of harmony, but rather, being so established in the minds of composers, the simple procedures of simple counterpoint were elaborated more and more until, apparently, there is no relationship between them. However, in his insightful and exhaustive text Counterpoint in Composition: The Study of Voice Leading, he systematically shows the relationship between the two.

First species

In the first kind of counterpoint, each note in each additional voice (voices we will also refer to as lines or parts) sounds against a note of the cantus firmus. The notes of all the voices sound simultaneously and move against each other at the same time. The species is said to be expanded if any of the added notes are fragmented (simply repeated).

Some additional norms given by Fux, after the study of Palestrina's style, and which are generally given in the works of later counterpoint pedagogues, are the following. Some are vague, and since good judgment and taste have been held by contrapuntalists to be more important than strict adherence to mechanical rules, there are far more precautions than prohibitions.

- Start and end in unison, eighth or fifth, unless the added voice is lower, in which case it starts and ends only in unison or eighth.

- Do not use unison except at first or at the end.

- Avoid the fifth or eighth parallels between any two voices and avoid the fifth or eighth parallel "ocultas". That is, it moves by direct motion towards a perfect fifth or eighth, unless a part (sometimes limited to voices) above) move by joint grades.

- Do not move in parallel quarters. (In practice, Palestrina and others frequently allow such progressions, especially if they do not involve the lowest of voices).

- Do not move in third or sixth parallels more than 3 times in a row.

- Try to keep two adjacent voices within a 10th distance between them, unless an exceptionally pleasant melodic line can be created moving out of that range.

- Avoid the two sides moving in the same direction by the jump.

- Try to introduce as much opposite movement as possible.

- Avoid dissonant intervals between any two voices: the second major and minor, the seventh minor, any increased or decreased intervals as well as the fourth perfect (in many contexts).

In the following two-voice example, the cantus firmus is the lowest part. (This same cantus firmus is also used in the following examples, which are in Doric mode.)

Second species

In the second kind of counterpoint, two notes from each of the added voices are counterposed to each longer note of the given voice. This species is said to be expanded if one of these two shorter notes differs from the other in length. Other additional considerations about this second species, which are added to the considerations for the first species, are the following:

- It is allowed to start in a weak time of the compass, leaving a white silence in the voice added.

- The strong time of the compass should contain only consonances (perfects or imperfect). The weak time may contain dissonances, but only as pace notes, that is, it must be addressed and resolved by joint degrees in the same direction.

- Avoid the unison interval except at the beginning or at the end of the example, with the exception that it can occur in an unincented part of the compass.

- Be careful with the successive perfect fifths or octaves, which should not be used as part of a sequential pattern.

The most interesting thing, as Schachter indicates in the book cited earlier in this section, is the effect generated by the second species in the course of a melody, that is, not so much the effect note by note, but the effect on the overall melodic line. In this sense, Schachter collects up to nine different possibilities.

Third species

In the third species of counterpoint, four (or three, etc.) notes move against each longer note of the given voice. As with the second species, it is called expanded if the shorter notes vary in length from one another.

Following Carl Schachter, as in the previous species, it should be remembered in relation to the third species that the interest of its study resides not only in the possibilities of the melodic line to evolve note by note, but also in the effect that the different melodic turns suppose the melodic line globally.

Fourth species

In the fourth species of counterpoint, some notes are held suspended in an added voice while other notes move against them in the given voice, often creating a dissonance on the downbeat, followed by the suspended note, and then changes (and "catch-ups") to create a further consonance with the given voice note as it continues to sound. As before, the fourth species of counterpoint is said to be expanded when the notes of the added voices vary in length from one another. The technique requires strings of notes held across the boundaries determined by the pulse, thus creating syncopation.

Fifth species or flowery counterpoint

In the fifth species of counterpoint, sometimes called flowery counterpoint, the other four species of counterpoint are combined in the added voices. In the example, the first and second measures are in second species, the third measure in third species, the fourth and fifth measures in third and fourth species and the last measure is in first species.

Contrapuntal derivations

Since the Renaissance in European music, much of the music considered contrapuntal has been written in imitative counterpoint. In imitative counterpoint, two or more voices enter at different times, and (especially on entry) each voice repeats some version of the same melodic element. The fantasia, the ricercare, and later the canon and fugue—the quintessential contrapuntal form—all display imitative counterpoint, which also appears frequently in choral pieces such as motets and madrigals. Imitative counterpoint has given rise to a series of resources that composers have resorted to to give their works both mathematical rigor and expressive range. Among these resources are the following:

- Melodic investment: the investment of a certain melodic fragment is that backwards fragment. In such a way that if the original fragment has a larger third interval, the inverted fragment will have a larger third descendant (or perhaps less), etc. (Note: In the counterpoint invertibleincluding counterpoint double and triplethe term investment is used in a completely different sense. At least a couple of voices are changed, so the one that was older becomes smaller. It is not a kind of imitation, but a reordering of the voices).

- Retrogradation: where the imitative voice interprets melody backwards in relation to the main voice.

- Retrograded investment: where the imitative voice interprets the melody back and down at the same time.

- Increase: when in one of the voices in imitative counterpoint the duration of the notes is lengthened compared to the value they had when they were introduced.

- Decrease: when in one of the voices in imitative counterpoint the duration of the notes is reduced compared to the value they had when they were introduced.

Shapes and structures

Among the musical forms developed applying the counterpoint technique, the following can be highlighted:

- La free imitationin which the main motive is developed in a voice that is imitated by one or more voices,

- La Canonical techniquein which one or more voices imitate the main motive more strictly. This strict imitation can be reversed, increased, retrograde, etc. resulting in the composition of a Canon,

- The multiple counterpointwhich can be double, triple, quadruple, etc. in which voices and countervoices relate to each other, usually from the first appearance of the main motive or theme, and the successive appearance and development of new voices, whether they are transported in intervals, appearing in investment, etc., giving rise to compositions of minor or greater complexity, such as the escape, whose most sophisticated examples can be considered the culmination of the counterpoint technique.

Carl Schachter, in his book Counterpoint in Composition: The Study of Voice Leading, includes the study of the Lutheran Chorale as one of the applications of study of counterpoint. Indeed, according to this author, the voices of the choir contrapuntally display basic chords of the tonality, generating a multitude of chords resulting from the movements of the four melodic voices.

Contenido relacionado

Peter and the wolf

Terry Jones

Gothic art