Coral

The marine corals are colonial animals, with few exceptions, belonging to the phylum Cnidaria, most of them to the Anthozoa class although some are of the Hydrozoa class (such as Millepora). Corals are made up of hundreds or thousands of individuals called zooids and can reach large dimensions. In tropical and subtropical waters they form large reefs. The term "coral" has no taxonomic meaning and different types of organisms are included under it.

Features

Although corals can catch plankton and small fish helped by the strokes of their tentacles, most corals obtain most of their nutrients from photosynthetic unicellular algae, called zooxantelas, living inside the coral tissue and They give color to this. These corals require sunlight and grow in clear and shallow water, usually at depths less than 60 meters. Corals can be the main taxpayers to the physical structure of coral reefs that were formed in tropical and subtropical waters, such as the huge great coral barrier in Australia and the Mesoamerican reef in the Caribbean Sea. Other corals, which do not have a symbiotic relationship with algae, can live in much deeper waters and in much lower temperatures, such as species of the genus Lophelia that can survive up to a depth of 3000 meters.

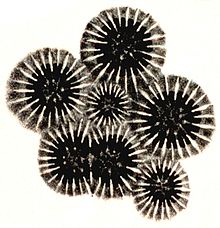

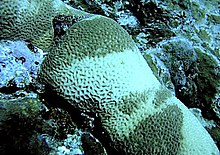

The term " Coral " It has no taxonomic meaning and is not precise; It is usually used to designate Antozoa in general, both those who generate a hard calcareous skeleton, especially those that build branched colonies, such as acroportes; but it is also common to call choral to species with compact colonies (" brain coral " such as lobophyllia ) and even with corneal and flexible skeleton, such as gorgonias. Likewise, the species of the Alcyonacea order are called soft corals, which do not generate skeleton and use calcium in the form of spicules distributed by their fleshy tissue, to provide greater rigidity and consistency.

both in the world of diving and in aquarium, corals are divided into soft and hard, depending on skeleton or not. And the hard ones, in turn, are subdivided into hard and hard polyp, " Small Polyp Stony " (SPS) Y " Large Polyp Stony " (LPS), in English. This classification refers to the size of the polyp, which in the SPS such as Montipora But this division is not very scientific and generates not a few exceptions under a rigorous analysis of the various species. The scientific community refers to micropolipos when coral polyps have between 1 and 2 mm in diameter, and alludes to macropolipos for those polyps between 10 and 40 mm in diameter. However, the vast majority of corals of all the world's reefs have polyps with a diameter between 2 and 10 mm, just among those categories.

CLASSIFICATION OF CORALES

Corals are divided into two subclasses based on the number of tentacles or lines of symmetry: Hexacorallia and Octocorallia, and a number of orders based on their exoskeletons, type of nematocyst, and mitochondrial genetic analysis. Common typing of corals crosses suborder/class boundaries.

Hermatypic Corals

Hermatypic corals are stony corals that build reefs. They secrete calcium carbonate to form a hard skeleton. They obtain a part of their energy requirements from zooxanthellae, (symbiotic photosynthetic algae).

Those that have six or less, or multiples of six, axes of symmetry in their body structure are called hexacorals (subclass Hexacorallia). This group includes the main reef-building corals, those belonging to the order Scleractinia (scleractinians). The other genera of hermatypic corals belong to the subclass Octocorallia (as Heliopora and Tubipora), and to the class Hydrozoa (as Millepora).

The ecological factors necessary for the growth of hermatypic corals are, among others:

- Relatively shallow water (from the surface to several tens of meters).

- Warm temperatures (between 20 and 30 °C).

- Normal salinities (between 27 and 40 °C).

- Strong penetration of light.

- Exchange with ocean waters open in high-energy agitated areas, which makes it clear waters, without suspension sediment and with some nutrient content.

- Firm substrate for anchorage.

In the Caribbean alone, there are at least 50 species of stony corals, each with a unique skeletal structure.

Some known types are:

- Coral brains, which can grow up to 1.8 meters wide.

- Acropora, which grow rapidly and may have a large size; they are important reef builders. Species like Acropora cervicornis They have great branches, something similar to deer horns, and inhabit areas with a strong wave.

- Dendrogyrawhich form columns that can reach a height of 3 meters.

- Leptopsammiawhich appears in almost all parts of the Caribbean Sea.

Ahermatypic Corals

Ahermatypic corals don't build reefs, because they don't build a skeleton. They have eight tentacles and are also known as octocorals, subclass Octocorallia. They include corals of the order Alcyonacea, as well as some species in the order Antipatharia (black coral, genera Cirrhipathes and Antipathes). Ahermatypic corals, such as gorgonians and Sessiliflorae, They are also known as soft corals. Unlike stony corals, they are flexible, undulating in water currents, and are often perforated, with a lacy appearance.

Their skeletons are proteinaceous rather than calcareous. The so-called soft corals and leather or skin corals, mostly fleshy in appearance, have in their tissues microscopic calcite crystals called spicules, whose function is to give consistency to the animal's tissue, in the absence of a skeleton itself. The shape and distribution of the spicules are the main characteristics used in the identification of genera and species of octocorals. Soft corals are slightly less abundant (20 species occur in the Caribbean, compared to 197 hard corals) than hard corals. stony corals.

Porous corals

Corals can be porous or non-porous. The former have porous skeletons that allow their polyps to connect to each other through the skeleton. Non-porous hard corals have solid, chunky skeletons.

Features

The animal known as coral, the polyp, measures from just a few millimeters to a few centimeters in diameter. Those of the order Scleractinia have the ability to fix calcium carbonate dissolved in the sea on their tissues and thus form the characteristic rigid structures.

The calcareous structure of coral is white, the different colors they present are due both to the different pigments of their tissues, as well as to other animal phyla, as well as to some microalgae that live in symbiosis with most coral polyps and which are called zooxanthellae. Only some genera of corals such as Tubastraea, Dendronephthya or part of the gorgonians are not photosynthetic. The algae carry out photosynthesis producing oxygen and sugars, which are used by the polyps, and feed on the coral's catabolites (especially phosphorus and nitrogen). This, in the case of photosynthetic corals, provides them with 70 to 95% of their nutritional needs. The rest is obtained by catching plankton. For this reason, the coral needs transparent waters to develop, so that the zooxanthellae carry out photosynthesis.

Non-photosynthetic corals are omnivorous animals, feeding on both zooplankton and phytoplankton or dissolved organic matter in the water.

Anatomy

In the 9th century century, the Muslim scholar Al-Biruni classified sponges and corals as animals, arguing that they respond to touch. However, corals were generally believed to be plants, until, in the 18th century, William Herschel used a microscope to determine that the corals had the thin cell membranes characteristic of an animal.

Colonial form

Polyps are interconnected by a common colonial tissue, called the coenchyma, composed of mesoglea in which polyps, sclerites, and gastrodermal canals are embedded. A complex and well-developed system of gastrovascular canals, which are used to significantly deliver nutrients and symbionts. In soft corals, these channels range in size from 50-500 micrometers (0.0050-0.050 cm) in diameter, and allow for the transport of cellular components and metabolites.

<IlipoAlthough a coral colony can give the visual impression of a single organism, it is actually a set that consists of many individual multicellular organisms, either that genetically identical, known as polyps. The polyps generally have a few millimeters in diameter, and are composed of an outer layer of epithelium and gelatinous internal tissue known as mesoglea. They are radially symmetrical, with tentacles that surround a central mouth, the only opening towards the stomach or celenteron, through which food is ingested and waste is expelled.

Exoesqueleto

The stomach closes at the base of the polyp, where the epithelium produces an exoskeleton called basal plate or calle (L. small cup). The calle is formed by a thickened calcareous ring (annular thickening) with six, or multiples of six, radial support crests. These structures grow vertically and are projected within the base of the polyp. When a polyp is physically stressed, its tentacles contract in the chalice so that virtually no part is exposed above the skeleton platform. This protects the body from predators and the elements.

The polyp grows, by extension of vertical calices that from time to time seizes to form a new upper basal plate. After many generations, these extensions constitute the large calcareous structures of the corals and finally the coral reefs.

<p The deposition speed, which varies greatly depending on the species and environmental conditions, can become 10 g/m² of polyp/day. This also depends on light, with night production being 90% lower than noon. The individual exoskeleton of each polyp is called Coralito.Tentacles

Nematocysts at the tips of the tentacles are stinging cells that carry venom, which are rapidly released in response to contact with another organism. The tentacles also have a contracting fringe of epithelium called the pharynx. Jellyfish and sea anemones also have nematocysts.

Food

Polyps feed on a variety of small organisms, from microscopic demersal plankton to small fish. The polyp's tentacles immobilize or kill their prey with their nematocysts (also known as a 'cnidocyte'). They then contract to direct the prey to the stomach. Once the prey is digested, the stomach reopens, allowing the expulsion of waste and the beginning of the next hunting cycle. Polyps also collect organic molecules and dissolved organic molecules.

Zooxanthellae Symbionts

Many corals, as well as other groups of cnidarians such as Aiptasia (a genus of sea anemones), form a symbiotic relationship with a class of algae, zooxanthellae, of the genus Symbiodinium, a dinoflagellate. Aiptasia, a known pest among coral aquarium hobbyists due to their overgrowth on live rock, serve as a valuable model organism in the study of cnidarian-symbiosis algae. Typically, each polyp harbors a species of algae. Through photosynthesis, these provide the coral with energy, and aid in calcification. Up to 30% of a polyp's tissue can be plant material.

Playback

As for reproduction, there are species of sexual reproduction and asexual reproduction, and in many species where both forms occur. The sex cells are expelled into the sea all at once, following signals such as lunar phases or tides. Fertilization is usually external, however, some species keep the ovule inside (gastrovascular cavity) and it is there where the eggs are fertilized; and the clutches are so numerous that they stain the waters.

Many eggs are eaten by fish and other marine species, but there are so many that, although the survival rate ranges between 18 and 25%, according to marine biology studies, the survivors guarantee the continuity of the species.

Once the eggs are outside, they remain adrift carried by the currents for several days, later a planula larva is formed which, after wandering through the marine water column, adheres to the substrate or rocks and begins its metamorphosis until it becomes a polyp and a new coral.

Sexual reproduction

Corals reproduce primarily sexually. About 25% of hermatypic corals (stony corals) form colonies composed of polyps of the same sex (unisexual), while the rest are hermaphrodite.

Dissemination

About 75% of all hermatypic corals spawn by diffusion, releasing egg gametes and sperm into the water to propagate their offspring. The gametes fuse during fertilization to form a microscopic larva, called a planula, typically pink in color and elliptical in shape. A coral colony produces thousands of larvae per year to overcome the obstacles that make it difficult for a new colony to form.

The synchronous spawning is very typical in coral reefs, and often, even when several species are present, all corals spawn on the same night. This synchrony is essential to allow male and female gametes to be found. The corals trust environmental signals, which vary from species to species, to determine the appropriate time to spread the gametes. These signals include temperature changes, lunar cycle, duration of the day, and possibly chemical signals. Synchronous spawning can form hybrids and is possibly involved in the choral speciation. The immediate signal for spawning is often the sunset The event can be visually spectacular, when millions of gametes are concentrated in certain areas of the reefs.

Incubation

Incubating species are often ahermatipic (they are not constructors of reef) and inhabit areas with a lot of waves or strong water currents. Incubating species only release sperm without flotability, which sink the egg carriers waiting with non -fertilized eggs for weeks. However, it is also possible that it occurs synchronous with these species. After fertilization, the corals release plánules, ready to settle in an adequate substrate.

<IlThe banners exhibit positive phototaxia, swimming towards the light to reach the surface waters where they derive and grow before descending in search of a hard surface to establish and start a new colony. They also exhibit positive sound, moving towards the sounds that emanate from the reef, moving away from open waters. Many stages of this process are affected by high rates of failure, and although thousands of gametes are released by the colony, there are few who achieve Form a new colony. The period of spawning to settlement in a new hard substrate general asexual.

Asexual reproduction

Within a coral colony, genetically identical polyps reproduce asexually, either through geming (loans) or by longitudinal or transverse division; Both are shown in the photo of Orbicella Annularis .

Gemination

" Gemination " It consists of separating a minor polyp from an adult. As the new polyp grows, body parts are formed. The distance between the new polyp and the adult grows, and with it, the coenosarco (the common body of the colony; see anatomy of a polyp). Gemation can be:

- Intratentacular: from their oral records, producing polyps of the same size within the ring of tentacles.

- Extratentacular: from its base, producing a smaller polyp.

Division

"Division" forms two polyps, as large as the original. "Longitudinal division" it begins when a polyp widens and then divides its coelenteron, analogous to the longitudinal division of a trunk. The mouth also splits and forms new tentacles. Then the two "new" polyps generate the other body parts and the exoskeleton. "Cross division" It occurs when the polyps and the exoskeleton divide transversely into two parts. This means that one part has the basal disc (the bottom part) and the other part has the oral disc (top part), similar to cutting the end of a log. The new polyps have to generate the missing pieces individually.

Asexual reproduction has several benefits for these sessile colonial organisms:

- Cloning allows high reproductive rates and rapid exploitation of the habitat.

- Modular growth allows the increase of biomass without a corresponding decrease in the surface-volume ratio.

- Modular growth delays sensence, allowing the clone to survive the loss of one or more modules.

- The new modules can replace the dead modules, reducing clone mortality and preserving the territory occupied by the colony.

- Dissemination of clones to distant places reduces mortality among clones caused by localized threats.

Colony Division

Entire colonies can reproduce asexually, forming two colonies with the same genotype.[citation needed]

- "Fision" occurs in some corals, particularly within the Fungiidae family, in which the colony is divided into two or more colonies during the early stages of development.

- "Abandon" occurs when a single polyp leaves the colony and settles on a different substrate to create a new colony.

- "Fragmentation" involves individual colony-disaggregated polyps during storms or other disturbances. Separate polyps can start new colonies.

Coral Reefs

Coral polyps die over time, but the calcareous structures remain and can be colonized by other coral polyps, which will continue to create calcareous structures generation after generation. Large calcareous structures known as coral reefs form over thousands or millions of years.

Sometimes the reefs are so big that they can even emerge from the surface. Thus, when coral grows around a volcanic island that subsequently subsides, a ring-shaped coral structure with a central lagoon is created, which is called an atoll.

The longest reef is the Great Barrier Reef, off the coast of Queensland in Australia: it is more than 2000 km², and it is one of the largest natural constructions in the world. The region of the world with the most coral species and the most biodiversity in its coral reefs is the Coral Triangle, in Southeast Asia, which includes more than 500 coral species (76% of known coral species) and at least 2,228 species of fish.

Coral reefs are home to many marine organisms that find food and protection from predators there.

The second largest coral reef in the world, the Mesoamerican Reef (along the coast of Mexico, Belize, Guatemala and Honduras), is located in the Caribbean Sea, and extends for more than 700 km from the peninsula from Yucatan to the Bay Islands off the north coast of Honduras. Although one-third the size of Australia's Great Barrier Reef, the Mesoamerican Caribbean Reef is home to a great diversity of organisms, including 60 types of coral and more than 500 species of fish.

The ecosystem is also the site of two major international conservation initiatives, one already well established and one just in its infancy.

In 1998, the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) identified the Mesoamerican Caribbean reef as a priority ecosystem and an ecoregion of global importance, thus beginning a long-term conservation effort for the reef. term.

Evolutionary history

Although corals first appeared during the Cambrian, 542 million years ago, corresponding fossils are extremely rare until the Ordovician period, 100 million years later, when the distribution of rough and tabular corals became widespread..

The fossil record of tabulate corals is found in Ordovician and Silurian limestone and shale, and they often form low cushions or ramifications next to rugose corals. Their numbers began to decline in the middle of the Silurian, and they became extinct at the end of the Permian, 250 million years ago. The skeletons of tabulated corals are made up of a form of calcium carbonate known as calcite.

Rough corals became dominant in the mid-Silurian, and became extinct in the early Triassic. Rugged corals lived solitary and in colonies, and their exoskeletons were also made of calcite.

Scleractinian corals filled the gap left by extinct rugose and tabulate coral species. Their fossils can be found in small numbers in rocks from the Triassic period, and they became common from the Jurassic. Scleractinian skeletons are made up of a type of calcium carbonate known as aragonite. Although they are geologically younger than tabulate and rough corals, their fossil record is less complete due to their aragonite skeleton, which is more difficult to preserve.

| |

Chronogram of the coral fossil record and of the main events from 650 Ma to the present. | |

Corals were very abundant at certain times in the geological past. Like modern corals, these coral ancestors built reefs, some of which ended up as large structures in sedimentary rocks.

Fossils of other reef inhabitants, such as algae, sponges, and the remains of many echinoderms, brachiopods, bivalves, gastropods, and trilobites, appear along with coral fossils. The distribution of coral fossils is not limited to reef remains, as many solitary fossils can be found elsewhere, such as Cyclocyathus which occurs in the Gault Clay Formation in England.

Conservation status

Threats

According to some studies, coral reefs are in decline worldwide. The main localized threats to coral ecosystems are coral extraction, agricultural and urban runoff, organic and inorganic pollution, overfishing, blast fishing, coral diseases and the excavation of access channels to islands and bays. Broader threats include rising sea temperatures, rising sea levels, and pH change due to ocean acidification, all associated with greenhouse gas emissions. In 1998, the 16 % of total coral reefs died as a result of rising sea temperatures.

Water temperature changes of more than 1-2 degrees Celsius, or changes in salinity, can decimate corals. Under such environmental pressures, corals expel their zooxanthellae; without them, coral tissues reveal the white of their skeletons, an event known as coral bleaching.

Global estimates indicate that approximately 10% of all coral reefs are dead. About 60% of coral reefs are at risk as a result of human activities. It is estimated that the destruction of coral reefs could reach 50% in the year 2030.[citation needed] In response, most nations established environmental laws in a attempt to protect this important marine ecosystem.

Between 40% and 70% of common algae transfer lipid-soluble metabolites and cause bleaching and death among corals, particularly when there is an overgrowth of algae. Algae proliferate when they have sufficient nutrients as a result of organic contamination., and if overfishing dramatically reduces grazing by herbivores, such as parrotfish.

Protection

Coral reefs can be protected from anthropogenic damage if they are declared protected areas, eg marine protected area, biosphere reserve, marine park, national monument, world heritage site, fisheries management and habitat protection.

Many governments now ban coral removal from reefs and inform coastal residents about their protection and ecology. Although local measures, such as marine herbivore habitat protection and restoration, can reduce local damage, global and longer-term threats such as acidification, temperature change, and sea level rise remain a challenge. In fact, recent studies have found that in 2016 approximately 35% of corals died in 84 areas of the northern and central sections of the Great Barrier Reef, due to coral bleaching caused by the increase in sea temperature. sea.

Some coral genera and species

Contenido relacionado

Rhinocerotidae

Pan paniscus

Bovidae

Dugong dugon

Gekkonidae