Constitutional monarchy

The constitutional monarchy, as opposed to the absolute monarchy, is a form of government, in which there is a separation of powers, where the monarch holds the executive power by naming the government, while the power Legislative, it is exercised by an assembly or parliament, usually elected by the citizens.

Political science distinguishes between constitutional monarchy and parliamentary monarchy. In constitutional monarchies, the king retains executive power. On the other hand, in parliamentary monarchies, the executive power comes from the legislature, which is elected by the citizens, the monarch being an essentially symbolic figure.

Although the current monarchies are mostly parliamentary, historically this has not always been the case. Many of the monarchies have coexisted with fascist (or in practice fascist) constitutions, such as in Italy (since 1861, a constitutional monarchy governed by the Albertino Statute of 1848, but which from 1922 coexisted with the dictatorial regime of Benito Mussolini) or Japan (the 1889 Japanese constitution attributed extensive military and political powers to the emperor), or with military government dictatorships as in Thailand, in 2007.

History

The oldest constitutional monarchy dating back to antiquity was that of the Hittites. They were an ancient Anatolian people who lived during the Bronze Age whose king had to share his authority with an assembly, called the Panku , which was the equivalent of a deliberative assembly or an actual legislature. Members of the Panku came from scattered noble families who worked as representatives of their subjects in a subaltern or adjunct federal type setting.

The constitutional monarchy was an intermediate or evolved step before the appearance of the first modern republics such as the United States and France, especially in the XIX century . It was intended to go from absolute monarchies, maximum representatives of the Old Regime, to parliamentary monarchies with limited power.

The Constitution of 1791 established a constitutional monarchy in France. The royal authority was subordinated to that of the law. It confirmed the separation of powers, the legislative power corresponded to a unicameral assembly of 745 members elected for two years and indissoluble. King Louis XVI was in charge of the executive power, freely appointing and revoking his ministers, he did not have the power to legislate or financial power, he could not dissolve the assembly, but he had the right to a suspensive veto, for four years, to the laws that he judged. unfair or inconvenient. The constitutional monarchy ended on September 21, 1792 when the legislative assembly proclaimed the abolition of the monarchy, giving way to the French First Republic. Later the July Monarchy (1830 to 1848) was also a constitutional monarchy, granting King Louis Philippe I of France executive power and the bicameral parliament legislative power. The German Empire (Deutsches Reich, 1871-1918) was also a constitutional monarchy at the federal level.

Constitutional and absolute monarchy

England, Scotland and the United Kingdom

In the Kingdom of England, the Glorious Revolution of 1688 promoted the constitutional monarchy, restricted by laws such as the Bill of Rights 1689 and the Act of Establishment of 1701, although the first form of constitution was promulgated with the Magna Carta of 1215 At the same time, in Scotland, the Convention of States enacted the Claim of Rights Act 1689, which placed similar limits on the Scottish monarchy.

Although Queen Anne was the last monarch to veto an Act of Parliament when she blocked the Scottish Militia Bill on March 11, 1708, Hanoverian monarchs continued to selectively dictate government policy. For example, King George III consistently blocked Catholic Emancipation, which eventually precipitated the resignation of William Pitt the Younger as Prime Minister in 1801. The sovereign's influence on the choice of Prime Minister gradually declined during this period, King William IV was the last monarch to remove a Prime Minister, when in 1834 he removed Lord Melbourne as a result of Melbourne's election of Lord John Russell as Leader of the House of Commons. Queen Victoria was the last monarch to serve a true personal power, but this was diminishing throughout his reign. In 1839, she became the last sovereign to keep a Prime Minister in power against the will of Parliament, when the Bedchamber Crisis led to the retention of Lord Melbourne's administration. Late in her reign She was, however, unable to do anything to block William Gladstone's unacceptable (to her) debuts, although she continued to exercise her power in Cabinet appointments, for example in 1886 preventing Gladstone's election of Hugh Childers as Secretary of War in favor of by Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman.

Today, the role of the British monarch is, by convention, effectively ceremonial. Instead, the British Parliament and the Government - primarily in the office of Prime Minister of the United Kingdom - exercise their powers by virtue of the & #34;Royal (or Crown) Prerogative": in the name of the monarch and through the powers still formally possessed by the monarch.

No person may accept important public office without taking an oath of allegiance to the Queen. With few exceptions, the monarch is bound by constitutional convention to act on the advice of the Government.

Continental Europe

Poland developed the first constitution for a monarchy in continental Europe, with the Constitution of May 3, 1791; it was the second single-document constitution in the world just after the first Republican United States Constitution. Constitutional monarchy also existed briefly in the early years of the French Revolution, but much more widely afterwards. Napoleon Bonaparte is considered to have been the first monarch to proclaim himself the embodiment of the nation, rather than a divinely appointed ruler; This interpretation of the monarchy is typical of continental constitutional monarchies. The German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, in his work Elements of the Philosophy of Law (1820), gave the concept a philosophical justification that coincided with the evolution of contemporary political theory and with the Christian vision of natural right of the Protestant. Christian natural law. Hegel's envisioning of a constitutional monarch with very limited powers whose role is to embody the national character and provide constitutional continuity in times of emergency was reflected in the development of constitutional monarchies in Europe and Japan.

Executive Monarchy vs. Ceremonial Monarchy

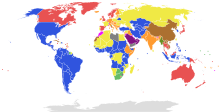

There are at least two different types of constitutional monarchies in the modern world: executive and ceremonial. In executive monarchies, the monarch exercises significant (though not absolute) power. The monarchy under this system of government is a powerful political (and social) institution. By contrast, in ceremonial monarchies, the monarch has little or no real power or direct political influence, although they frequently have great social and cultural influence.

Executive constitutional monarchies: Bhutan, Bahrain, Jordan, Kuwait, Liechtenstein, Monaco, Morocco, Qatar and Tonga.

Ceremonial constitutional monarchies (informally referred to as crowned republics): Andorra, Antigua and Barbuda, Australia, Bahamas, Belgium, Belize, Cambodia, Canada, Denmark, Grenada, Jamaica, Japan, Lesotho, Luxembourg, Malaysia, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Papua New Guinea, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Solomon Islands, Spain, Sweden, Thailand, Tuvalu, and the United Kingdom.

Ceremonial and executive monarchy should not be confused with democratic and non-democratic monarchical systems. For example, in Liechtenstein and Monaco, the ruling monarchs wield significant executive power. However, they are not absolute monarchs, and these countries are generally considered democracies.

Modern constitutional monarchy

As originally conceived, a constitutional monarch was the head of the executive branch and a fairly powerful figure, though his power was limited by the constitution and elected parliament. It is possible that some of the framers of the United States Constitution conceived of the president as an elected constitutional monarch, as the term was then understood, following Montesquieu's account of the separation of powers.

The current concept of constitutional monarchy developed in the United Kingdom, where democratically elected parliaments, and their leader, the prime minister, wield power, with monarchs ceding power and remaining in office. In many cases, the monarchs, while remaining at the top of the political and social hierarchy, came to have the status of "servants of the people" to reflect the new egalitarian position. During the French July Monarchy, Louis Philippe I was called the "King of the French" instead of "King of France".

After the unification of Germany, Otto von Bismarck rejected the British model. In the constitutional monarchy established under the Constitution of the German Empire that Bismarck inspired, the Kaiser retained considerable royal executive power, while the Imperial Chancellor needed no parliamentary vote of confidence and ruled solely by imperial mandate. However, this model of constitutional monarchy was discredited and abolished after the defeat of Germany in World War I. Later, Fascist Italy could also be considered a constitutional monarchy, as there was a king as titular head of state, while real power was held by Benito Mussolini under a constitution. This eventually discredited the Italian monarchy and led to its abolition in 1946. After World War II, the surviving European monarchies almost always adopted some variant of the constitutional monarchy model originally developed in Britain.

Today, a parliamentary democracy that is a constitutional monarchy is considered to differ from one that is a republic only in details and not in substance. In both cases, the incumbent head of state - the monarch or the president - performs the traditional role of embodying and representing the nation, while government is carried out by a cabinet made up predominantly of elected Members of Parliament.

However, there are three important factors that distinguish monarchies like the UK from systems where the greatest power might rest with Parliament. These are: the Royal Prerogative, by virtue of which the monarch can exercise power in certain very limited circumstances; Sovereign Immunity, by virtue of which the monarch cannot do anything wrong before the law because the responsible government considers itself responsible instead; and the monarch may not be subject to the same tax or property use restrictions as most citizens. Other privileges may be nominal or ceremonial (for example, when the executive, judiciary, police or armed forces act under the authority of the Crown or owe allegiance to it).

Today, just over a quarter of constitutional monarchies are Western European countries, including the United Kingdom, Spain, the Netherlands Monarchy, Belgium, Norway, Denmark, Luxembourg, Monaco, Liechtenstein and Sweden. However, the two most populous constitutional monarchies in the world are in Asia: Japan and Thailand. In these countries, the prime minister holds the day-to-day powers of government, while the monarch retains residual (although not always insignificant) powers. The monarch's powers differ from country to country. In Denmark and Belgium, for example, the monarch formally appoints a representative to preside over the formation of a coalition government following parliamentary elections, while in Norway the King chairs special cabinet meetings.

In almost all cases, the monarch remains the head of the nominal executive, but is bound by convention to act on the advice of the Cabinet. Only a few monarchies (most notably Japan and Sweden) have changed their constitutions so that the monarch is no longer even the nominal head of the executive.

There were fifteen constitutional monarchies under Queen Elizabeth II, which are known as Commonwealth realms. Unlike some of their continental European counterparts, the monarch and her Governors-General in Commonwealth realms hold important "reserve" or "prerogative", which are exercised in moments of extreme emergency or constitutional crisis, normally to maintain parliamentary government. One instance where the Governor General exercised this power occurred during the Australian constitutional crisis of 1975, when Australian Prime Minister Gough Whitlam was removed by the Governor General. The Australian Senate had threatened to block the government's budget by refusing to pass the necessary appropriation bills. On November 11, 1975, Whitlam intended to call a mid-Senate election to try to unblock the situation. When he requested the approval of the elections by the governor-general, the governor-general removed him as prime minister. Shortly thereafter he installed opposition leader Malcolm Fraser in his place. Acting quickly, before all MPs knew of the change in government, Fraser and his allies got the Appropriations Bills through, and the Governor-General dissolved Parliament for a double-dissolution election. Fraser and his government returned with a large majority. This gave rise to much speculation among Whitlam's supporters as to whether this use of the Governor-General's reserve powers was appropriate, and whether Australia should become a republic. However, among supporters of the constitutional monarchy, the experience confirmed the value of the monarchy as a source of checks and balances against elected politicians who might seek powers in excess of those conferred by the constitution, and ultimately as a safeguard against to the dictatorship.

In Thailand's constitutional monarchy, the monarch is recognized as Head of State, Head of the Armed Forces, Defender of the Buddhist Religion, and Defender of the Faith. The immediate previous king, Bhumibol Adulyadej, was the longest-serving monarch he reigned over the world and throughout Thai history, before passing away on October 13, 2016. Bhumibol reigned through various political changes in the Thai government. He played an influential role in each of them, often acting as a mediator between feuding political opponents. (See Bhumibol's role in Thai Politics. Among the powers retained by the Thai monarch under the Constitution, lèse majesté protects the monarch's image and allows him or her to play a role in politics. It carries strict criminal penalties for violators. Bhumibol is generally revered by the Thai people, and much of his social influence arose from this reverence and from the socio-economic improvement efforts undertaken by the royal family.

In the UK, a frequent debate centers on when it is appropriate for a British monarch to act. When a monarch acts, political controversy often ensues, partly because the neutrality of the crown is seen as being compromised in favor of a partisan objective, while some political scientists advocate the idea of an "interventionist monarch." 3. 4; as control of possible illegal actions of politicians. For example, the monarch of the United Kingdom can, in theory, exercise an absolute veto over legislation by denying royal assent. However, no monarch has done so since 1708, and the general opinion is that this and many other political powers of the monarch are expired powers.

There are currently 43 monarchies around the world.

Contenido relacionado

Sacred united crown

Clash of civilizations

Chilean political parties