Conservatism

In political philosophy, conservatism in a broad sense refers to the set of doctrines and political movements that favor the use of political power or the force of the State to preserve or restore traditions —beliefs or customs— of a people or nation that can be religious, cultural or political. In these cases the term conservatism is understood as traditionalism in politics or keeping a present political order intact — or as reactionary or restoring a lost political order.

Across the political spectrum, because of conservatives' favorable assessment of the pecking order, they are often considered to be on the political right, however, conservatives can also be found, to a lesser extent, on the political left.

On economics, conservatives have historically positioned themselves as protectionists, in opposition to free markets. However, during the 20th century, some of the conservative parties adopted neoliberal economic positions as a Cold War influence, allies in the defense of the capitalist socioeconomic system, in opposition to communism. Consequently, in the XXI century, within political conservatism various positions on economics coexist.

Beginnings of conservative philosophy

The term "conservative" was introduced into the political vocabulary by Chateaubriand in 1819 to refer to those who opposed the ideas antecedent and resulting from the French Revolution or, more generally, the ideas and principles that emerged during the Enlightenment, and that to some extent they planned the restoration of the Old Regime. This opposition, which had specific characteristics in different countries, was strengthened as a consequence of the events of that revolution and the wars. Thus, for example, Michael Sauter writes: "To conclude, conservatism is a product of both the pre-revolutionary and revolutionary periods of France. It has various origins and appeared in various countries in different forms. But if there is anything we can say about its history, it is that the French Revolution provided the impetus for turning conservatism into a movement. Those who had campaigned against any change before 1789 suddenly became prophets." Or, in the words of a modern figure who considers himself a conservative: "The roots of evil are historical-genetically the same throughout the Western world. The fatal year is 1789, and the symbol of inequality is the Phrygian cap of the Jacobins. Their heresy is the denial of personality and personal freedom. Its concrete manifestation is Jacobin mass democracy, all forms of national collectivism and statism, the Marxism that produces socialism and communism, fascism and national socialism. Leftism in all its varieties and modern manifestations, to which in the US the term liberalism is perversely applied."

The fundamental difference between moderate and reactionary conservatism lies in their vision of the role of democracy and other modernist institutions or products of the Enlightenment. For the moderate tradition, perhaps best found in "the liberal conservatism of Edmund Burke (1729-1797), unlike the continental conservatism of his day, accepted democracy as a form of government". This conservatism "In fact (....) brought far-reaching and far-reaching changes (British political rights, or Bismarckian social rights)", This version of conservatism is often called "liberal", thus, for example, Rosemary Radford Ruether observes: " There is an economic and political conservatism, free market, capitalism free from any government regulation, usually coupled with a strong nationalism, like the number one in the world, which leads to prioritizing support for the police and a large budget for the army.. This type of conservatism is not traditionally religious or connected to Christianity". Such conservatism, prevalent especially in the Anglo-Saxon world, tends to see history as a continuous trial and error where one must learn from the past, and adopt from it. those things that have worked best.

However, it should be mentioned that it was this same moderate current that later gave rise to a fundamentalist conservatism, which Radford Ruether defines as emanating from "properly Protestant fundamentalism" (op cit). This version has generally found expression in the neoconservatism which is represented by characters such as Leo Strauss and Irving Kristol, etc. and is characterized by not rejecting economic liberalism and traditional nationalist and religious values in the social and political spheres.

The other great current of conservatism appeared in the countries that were directly affected by the political and social developments of the French Revolution, «in rejection of it, of political liberalism and of the rationalism of the Enlightenment, defending the institutions of the Ancien régime and declaring himself an enemy of the secularization of politics and society. Conservatism or conservatism, as it is also known, is based on three values: authority, loyalty and tradition. It pays homage to spirituality and the value of the immeasurable." In that sense, it can be described as "reactionary", seeking a reaffirmation, not only of political forms, but of previous social ones, which were perceived as a restoration of the principles of absolute monarchical authority and (generally) Catholicism as the only source of values and social stability: «French conservatives oscillated towards the Catholic Church as a source of stability and tradition. The Church brought back to everyday life a sense of hierarchy and organic order (Of course there is an implicit connection to Romanticism here.)" But in the Catholic regions of Europe, especially France, Italy and Spain, this type of religious conservatism would have an inherent attraction.

An extreme development of the latter position is found in the suggestions of Carl Schmitt, who was one of the main ideologues of the Conservative Revolutionary Movement in Germany. His proposal is based on the affirmation that the central function of a State is the need to establish an effective "decision" power, which ends the internal war, something that is not possible, in his opinion, in a liberal State, in which the demand for the sacrifice of life in favor of political unity cannot be justified. These suggestions had, together with others from the Conservative Revolutionary Movement, an important influence in the rise to power of Nazismand still today constitute the theoretical bases of both "hard" as the modern origin of the alleged tendency of conservatism to depend on leaders or "men of the moment".

International presence

United Kingdom

Many commentators point out that the origin of English conservatism can be found in the ideas of Richard Hooker, a theologian of the Anglican Church, who developed his ideas as a result of the Reformation. Hooker emphasizes the importance of moderation in order to obtain a political balance in order to achieve social harmony and the common good, thus giving rise to what, in England, is called "High Conservatism", which can be seen as "high conservatism". moderate” or even as an expression of the center right.

Another of the crucial thinkers of English conservatism was Edmund Burke. In his book Reflections on the French Revolution, Burke criticizes the rationalism of the Enlightenment and denies the possibility of founding a society in the emancipatory capacity of reason, a project that he considers utopian. In response to these positions of liberalism of the 18th century, Burke proposed a return to the fundamental traditions of European society and the values Christians based on social naturalism. This position is based on the idea that not everyone is born equal, with equivalent capacities or reason, and therefore a government based on the reason of individuals could not be trusted. The traditions, on the other hand, contained the proven ability to regulate social functioning with stability. However, Burke does not deny the need for social change, but questions its speed. For him, the social order remains and evolves through a natural process, as an organic whole.

Burke conceived the establishment of the ideal state (exemplified in the English system) as based on the laws, liberties and customs that result from a kind of social contract between the various social sectors. That contract is reflected —in the case mentioned— in the Bill of Rights. This contract precedes —and is threatened by— the appearance of absolute monarchies, which must be controlled but not exterminated, as was the result of the Glorious Revolution. In Burke's opinion, this contract not only regulates the relations between the different Estates or social classes, but establishes the "old liberties" and guarantees that correspond to each one, adding that it is from the opposition of those interests, resolved in the In a manner approved in the constitution, they emanate from and secure not only harmony but also the aforementioned liberties. In short, Burke is a strong supporter of constitutional monarchy which he sees as based on ancient rights—which precede or are at the very foundation of that system and that are transmitted by right of inheritance and that are expressed in Parliament (see "Origin of the Institution" in that article)— A system that he considers harmonious and stable not only because "in a kind of true social contract" it allows that the various 'property types' (nobility, church and merchants or bourgeois in the original sense of the word: those who live in cities) can solve their problems but also because "the common people" accept and endorse that system to the extent that it guarantees prosperity. Additionally, Burke argued that traditions are a much more stable source of political action than "metaphysical abstractions" that, at best, represent only the best of a generation, as opposed to the accumulated wisdom of traditions, which influence individuals in such a way. in a way that makes it impossible to make "objective judgments" about society.

Burke has come to have a lot of influence on conservatism not only in Anglo-Saxon but also in other nations due to, among other things, his ideas about the Law of Unintended Consequences and "moral hazard"., and in apparent opposition to the Christian origin of his ideas, Burke also defended private property, which has been one of the central elements of conservatism to this day.

Another thinker of great importance for this vision was Benjamin Disraeli, who, despite being a conservative, was sympathetic to some of the demands of the "chartists" and introduced -indirectly- the term "conservatism of a nation" to refer to to an aspiration for national unity and harmony between social classes and interest groups.

Consistent with this position, Disraeli sought a political agreement with the "radicals", in opposition to the liberal policies of the time, specifically, in relation to extending the vote to popular sectors (at that time, the right to vote was restricted to men who were property owners). However such attempts were unsuccessful, one Chartist leader noting (in his diary) that "Disraeli seems incapable of understanding the moral (basis) of our political position." Disraeli was apparently prepared to offer cabinet positions in exchange for political support..

Despite these failures, Disraeli continued to promote "unitary" or reformist policies: the reduction of indirect taxes and the staggering of direct taxes in relation to income, the "Reform Act of 1867" (or "Representation of the People Act 1867”) which extended the right to vote to the urban working classes (the number of voters doubled); It gave representation in Parliament to fifteen cities that did not previously have it and extended that of the great Chartist centers: Manchester and Liverpool. At the same time, he abolished "compounding," a system in which tenants paid not just rent, but interest on it (unless they paid in advance, which most workers obviously weren't in a position to do)..

Later Disraeli promoted

- laws permitting peaceful demonstrations during industrial conflicts (1875),

the right of employees to sue employers for breach of contract conditions (1875),

- the Public Health Act (1875), which forced builders and tenants to provide housing with certain minimum conditions (such as drinking water and connections to health services),

- the Law on the Improvement of the Houses of Artisans and Workers (1875), which established the obligation of municipalities to eliminate unhealthy populations and to build others with minimal conditions,

- the Sales Act (1875), which regulates the quality of these articles, and

- the Education Act (1876).

In matters of foreign policy, Disraeli was inclined to promote the "greatness" of the United Kingdom through a tough policy, without concessions to sentimentality, putting national interests above moral considerations. In this sense, Disraeli was he leaned towards "protectionism" when circumstances permitted.

British Conservative politicians pursued "one nation" policies until the mid-1970s of the XX century. Prominent among them are Harold Macmillan, who favored a mixed economy system and was one of the central figures in establishing the consensus that produced the English welfare state.

Subsequently, conservatism in England adopted the political-economic visions of the Chicago school with the appointment of Margaret Thatcher as leader of the Conservative Party, who violently opposed that "one nation" consensus and what she perceived as the excessive power of the unions. His vision resulted in one of the worst times of social tensions on British soil.

Despite the apparent success of her economic policies, Thatcher was perceived, even within the Conservative party, as given to extremism and as glorifying herself in confrontation and divisiveness, through issuing statements and acting in ways that she knew would be controversial, such as when—in January 1978—she said "people are really worried that this country might be flooded by people with a different culture", (which was interpreted as an attempt to attract the racist sector of the population). The reference to the unions as "the enemy within", the European project as "a superstate", his thanks to General Augusto Pinochet (former Chilean dictator) for "establishing democracy in Chile" which put the conservative party in a difficult position, the controversial abolition of municipalities that were controlled by opposition parties. Equally controversial was her statement to French newspapers that “human rights do not begin with the French Revolution” and that “there is no such thing as society.” That confrontational attitude extended even to those who could be assumed to be her natural allies. her. For example, when—after being elected leader of the Conservative Party—it was suggested that she bring into her "opposition cabinet" some figures from among those who had supported others for the post of leader—as a gesture of reconciliation and unity—her The answer was that those were his enemies, and enemies are given no quarter but destroyed.

These attitudes and policies came to be known, originally, as "Thatcherism" and, later, as neoliberalism.

The British Conservative leader, David Cameron seems to want to abandon those policies and return to the previous ones under the name of a «compassionate conservatism}: «A modern and compassionate conservatism. This is the right thing to do in these times." Today the Conservative Party has managed to re-establish its support with the falling popularity of the Labor Party (UK) and the inability of the Liberal Democrat Party to win broad support.

France

In 1796, Louis de Bonald defined conservative principles as: «absolute monarchy, hereditary aristocracy, patriarchal authority in the family, and the religious and moral sovereignty of the popes over all the kings of Christendom», in his work « Theorie du pouvoir politique et religieux».

Joseph-Marie, Comte de Maistre is one of the most prominent representatives of "religious authoritarianism" in the period immediately following the French Revolution. Deeply influenced by the thought of Jakob Böhme, Louis Claude de Saint-Martin and Emanuel Swedenborg, Joseph de Maistre radically opposed what he considered "theophobia of modern thought", which had relieved divine Providence of all importance as an explanatory element of phenomena of nature and society. Totally opposed to the ideas of the Enlightenment, for him the French Revolution (central subject of his reflections) was a satanic and "radically bad" event, both for its causes and its effects (Considerations on France (1797)). He also condemned democracy, for being a cause of social disorder, and was a firm supporter of the hereditary monarchy. This conservatism adds to religion the infallible spiritual power of the Pope with a fundamental function: to lead the fight against the historical decadence towards which humanity is heading (On the Pope, 1819).

The previous ideas were profoundly modified, particularly after the failure of the ideas of the «ultra-conservatives» —which led to a crisis that ended with the Revolution of 1830— with the spread of the ideas of Auguste Comte, for whom the order is found in the progress product of industrial growth, not in the return to the past. which has sometimes been summed up, in the words of the Brazilian motto, in the phrase: "Order and progress", which is a simplified version of this quote: "Love as a principle, order as a base and progress at last", which is found in his Course on Positive Philosophy (1826). Comte's intention was to restore the social system after the great changes produced by the French Revolution, but this restoration of order is based on an evolutionism or progressivism that can be seen as an attempt to establish a general political consensus that stabilizes the situation. during the period of the French Restoration. Comte's position thus gives rise to a conservative reformism that, unlike Burke's, is not openly monarchist, but is elitist, in that it postulates the right to govern for a reduced and educated minority of "positive scholars": "Comte claimed that temporary political power should be handed over to that sector. These were approaches that sought to manufacture a type of rationalist, scientific, and reliable social dirigismo, justified with the cloak of paternal protection that a privileged class could offer." This position is known as political or intellectual dirigismo

This position was later expressed in the French Action, the party of Charles Maurras that to this day is considered a representative of monarchist and ultranationalist conservatism in France. This sector demanded the restoration of the French monarchy as a result of the alleged lack of results and corruption that arose in the parliamentary regime. It was this sector that, as a result of the Dreyfus Case, gave rise to the "anti-intellectualism" that has become the main position of right-wing intellectuals to disqualify those who, despite being educated, did not accept the political implications of the proposed intellectual elitism. by Comte.

It also found expression, although more indirectly, in Gaullism, a movement considered moderate conservative or republican in France, which gave rise to "economic dirigisme".

Germany

Conservatism in Germany may be the first to be called "modern." Unlike the others, it takes into consideration the fact that there is social inequality that leads not only to poverty, but also to social instability. This introduces a fundamental change in the conception of the State, from what has been called the «Age of Rights» (typical of the 18th century) exemplified by the Declaration of Human Rights and the political Constitutions of various nations, etc., to a conception of the State as an expression of, in the words of Hegel, the «bürgerliche Gesellschaft» (civil society), in its broad sense of the State as the political-social structure of a nation. Consequently, Marx and others understand the term as meaning "bourgeois state"—note that bürger in its original sense means 'bourgeois' (ie, one who lives in a city or burg. It is more generally translated as citizen, but that is not the exact sense in Hegel, in which citizen has connotations of certain constitutional rights, etc.).

This conception is based on the critique of more traditional conceptions of the state, a critique found in the work of Hegel, who has been described as "trying to implement, from the Protestant point of view, what Thomas Aquinas he had tried to do six centuries earlier: design a synthesis of Greek philosophy and Christianity. It was Hegel who created the theoretical foundations for the integration into the German conservative vision of liberal "free market" economics in an authoritarian political system. For Hegel, the function of the state is to implement common moral principles ('Volkgeist') that exist a priori or above the community itself, rather than to represent the interests of individual members. Of the same. Those principles are embodied in a monarch who, since he is the embodiment of that & # 34; Volkgeist & # 34;, must be absolute. With this, Hegel not only establishes the bases for a political absolutism but gives form to the principle —deeply opposed to that of Enlightenment rationalism— that laws must be subject to morality (see, for example: Morality according to the philosophical current and compare, for example, originating from the legal system)

Additionally, for Hegel, the existence or creation of economic inequalities is an inevitable part of differences in human capabilities, but, unlike other conservatives (and "economic" liberals (contrast Social Liberalism) he did not consider this situation This inequality forces many to fall below the level necessary to be part of that "civil society", which encourages the creation of a "mob", which will inevitably have profoundly destabilizing effects for both the state and society. in general.

The foregoing implies that the development of the Institutional State on the basis of legal equality or, at least, minimum legal rights, cannot but lead to the need to legitimize that state by satisfying social needs. This in turn leads directly to Lorenz von Stein's proposal of a social state as a conservative measure. For von Stein, the duty of the state is to be above class conflict which, in the past and in its view, had meant that "the ruling classes" had "colonized the State" in order to "subjugate the working classes", which had only resulted in a revolution (The reference is to the French Revolution). This means that the State (monarchy) must both defend itself against these capitalists and prevent that revolution, which is achieved through state reformism or "illiberal capitalism".

All this materialized in the Bismarckian system of social reforms (called by some Rhenish Capitalism), which, through the "Deutsche Konservative Partei" (founded in 1876), managed to create a broad social alliance, encompassing the nobility, the evangelical church and other Christian sectors (including the so-called 'Social Christian' tendency), the big landowners, the supporters of the Bismarck government, such as Helmuth von Moltke, intellectuals such as the historian Hans Delbrück, etc. Of great importance in that period was the "Zeitschrift für Bergrecht" (Legal Magazine), which promoted these visions throughout the German-speaking territory, further facilitating German unification as a conservative nationalist and monarchical project. The magazine became internationally influential.

After World War I two tendencies made themselves felt in German conservatism. One is expressed not only in the National Socialist vision but also in an extreme or "radical" conservatism, such as, for example, in the vision of the Conservative Revolutionary Movement. This vision has been widely criticized in Germany for being one of the factors that legitimized the Nazi state. However, he played an important part in the great post-World War II debate in that country about the role of law in the context of the proposed constitution.

The alternative vision, which can be called conservative liberalism, is found in the Freiburg school (see also ordoliberalism) stressing the importance of institutional law, thus establishing the foundations for the modern Social State of Law. It should be remembered that one of the biggest points of contention in Bismarck's time was precisely a state refusal to establish a constitution. The Hegelian view—which Bismarck and the monarchy found it convenient to maintain—stated that the "volkgeist" found its highest, most developed expression, in a monarchy, in the individual who makes that national spirit a reality, that is, the absolute monarch.

After World War II, various politicians who constituted the Christian-inspired right-wing opposition and based on the visions of the Freiburg school, returned to more moderate visions of conservatism, reinterpreting the moral content of the Social State, seeking replace both nationalism and centralism in order to prevent the state from falling into the hands of despots. This new content, of a Christian nature, reaffirms not only the common good but also the irreplaceable value of the freedom of individuals and the value of the diverse communities that are integrated into a nation. Together with the economic conceptions of characters such as Franz Böhm, Walter Eucken and —mainly— Alfred Müller-Armack, they finally gave rise to the project of the Christian Democratic Union of Germany that came to be called the Social Market Economy.

United States

The history of conservatism in the United States is quite complex. There is debate in academic circles about whether or not there is a genuinely conservative current in political history in this country. Furthermore, it is common to affirm that there is no conservative ideology in the North American intellectual and political tradition —with ideological content equivalent to conservatism as it was founded as a political current in Europe— and that what is usually called conservatism in the United States. The USA are varieties of American liberalism. As in Latin America, after the Wars of Independence in the United States, conservatism lacked a monarchist current and, therefore, expressed itself in the maintenance of the existing social order and in the preservation of the emerging republican institutions, based on the ideas of George Washington, etc. To begin with, this was made explicit in the "Old Republican Party," which was called the United States Democratic-Republican Party at the time. However, the dominance of these "conservative" ideas—particularly the promotion of American interests at the regional and continental level—soon became general, thus giving birth to the so-called American consensus (see also Doctrine of Manifest Destiny).

Consequently, in the United States it is more pertinent to study conservatism in its different expressions. These meet—or affect—both political parties. Three main currents can be distinguished:

A social conservatism, strongly influenced by Christian fundamentalism, which can be considered as a direct descendant of Protestant visions about society and its organization. This position tends to see the government as having a legitimate role in supporting or even promoting social and moral values in society. However, there is no general agreement about what exactly those values would be, so it is difficult to generalize about them. However, and very generally, some common principles can be advanced: 1: Strict observation of divine laws and religious principles emanating from the Bible. Civil law must be based on moral principles. 2: The right of each individual and community to govern itself. 3: Individual and social success is a direct reflection of the "state of grace" that each individual and community has (or not), etc. This conservatism is ideological in that it is “millennial” or is intended to implement the founding of the New Jerusalem. However, and unlike other conservatisms, this tendency does not favor a strong state (despite the fact that it is patriotic), which reflects (or has given rise to) minarchist versions.

Although this tendency is not directly organized as a political party, it does have a lot of influence in politics, especially in matters of public opinion. Among those who could be said to represent her we find, for example: Bill O'Reilly; Rush Limbaugh; Jerry Falwell; Sarah Palin—the vice-presidential candidate—and, perhaps controversially, Pat Buchanan.

Another alternative, which can be called traditional or intellectual, in which it sees itself as heir to the best of both American and European conservatism, focuses its positions on a perception of the human being as an eminently moral entity, mainly valuing the role of the order and religion as a specific source of meaning in the lives of individuals and specifically rejecting any and all ideology.

This cultural conservatism (also called paleoconservatism by some of its adherents) emphasizes the role of the opinions of authorities in mores, laws, and social order. It also promotes the social function of hierarchies and faith, the "natural" family, "freedom in order", etc.

This position is explicitly nationalist —in that it proposes the pursuit of the national interest— but it is opposed to any direct extension of political power abroad (in the manner of European imperialism) proposing instead the creation and maintenance of alliances with governments whose interests coincide with those of the United States. This realpolitik has also given rise to an American conservative trend that justifies what some call US neocolonialism or imperialism (see, for example, the Monroe doctrine, the Big Stick, etc..) and can be summed up by saying that they are not opposed to the extension of US power, but they are opposed to the creation of colonies and, specifically, to intervention proposals in other countries in order to promote "progressive" political principles. » or democratic.

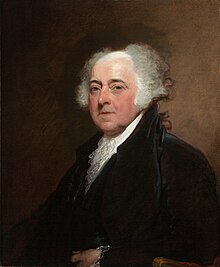

As representatives of this trend in its most contemporary version we find Samuel Phillips Huntington, Kathryn Jean López, Dinesh D'Souza and Russell Kirk who traced, in his The Conservative Mind, the development of thought conservative in the American tradition, from John Adams to George Santayana giving special importance to the ideas of Edmund Burke.

The third current of note is neoconservatism. This trend has been highly controversial, even for other conservative sectors, due to both its origins and objectives.

The main difference of neoconservatism from other conservative positions is in matters of international politics, on which neoconservatives advocate overtly interventionist policies to promote democracy as those that best serve the US interest both in the sense of establishing and maintaining an absolute predominance of that country as in order to maintain international order and peace, even if this implies that the US must practice unilateralism. In matters of economics, neoconservatives do not reject some degree of economic liberalism.

About the origin, it should be noted that among the founders and main theorists of this trend are many whose political origins go back to other visions —arriving at the present positions motivated by a strong anti-communist sentiment. Consequently they are under suspicion, from the traditional conservative point of view, of having "ideological" positions. For example, Irving Kristol was originally a Trotskyist while Michael Ledeen was a fascist.

The other theoretical source of neoconservatism is found in the work of a professor of politics —Leo Strauss— who spent his life in classrooms and about whom —during his life— few even knew his name. However, it is difficult to overestimate the importance of Strauss for the political life of the late XX and early XXI.

Strauss's positions are hugely controversial, and not just for conservatives in the US. Among other things, Strauss argues that arguments for the primacy of democracy are not necessarily correct or free from contradiction, so that he earned a reputation as an enemy of democracy. of political evolution or due to the natural development of reason or education, but, on the contrary, it is a political form that has been implemented, historically, by force, and therefore can or should be promoted from the same way.

Strauss leans in, noting that some first-rate thinkers—such as Plato—have questioned whether politicians can be completely honest and still achieve the ends they seek, because of the essential role of white lying in, for example, uniting or guide the members of a society, especially in order to ensure a stable society. In his The City and Man, Strauss studies the myths outlined in The Republic by Plato, myths used ever since by politicians in order to achieve and maintain social cohesion. These myths include the proposition that the lands of the "city" belong to its members as a community despite the fact that, in all probability, they were acquired illegitimately and that being a "citizen" or member of that society is based on things that go beyond that. the birthplace accident.

Thus, from Strauss's point of view, religion seems to be eminently a useful instrument of politics. This has given rise to a debate about whether the Straussian position on values is merely utilitarian and devoid of the content of transcendence or sense of the numen proper to more traditional conservatism. Some commentators even suggest that Strauss himself was an atheist. however this is debatable

According to Strauss, in political philosophy there are two central dichotomies: one of reason versus revelation. The other between the traditional versus the modern. The latter is related to matters of the public presentation of the tension —possibly irresolvable— between reason and revelation as political foundations and begins with Machiavelli, who would be the first of the moderns. The latter, reacting against the dominance of revelation-based politics during the Middle Ages, transform it—emphasizing the role of reason—into the politics of the market, thus beginning modern political problems.

According to him, liberalism contains a tendency to relativism (cultural and moral), which leads to a nihilism that is expressed, in liberal democracies, in a kind of intellectual wandering devoid of principles or values, in a hedonism, an egalitarian permissiveness that permeates American society.

Spain

The two expressions of conservatism —reactionary and moderate— became present after the French invasions at the beginning of the XIX century, first with the Manifesto of the Persians that seeks, under the direction of characters such as Francisco Tadeo Calomarde, the restoration of the Bourbons, thus giving rise to a particularly traditionalist or "reactionary" version of Spanishism that finally identified "the Spanish" with what is orthodoxly Catholic, in contrast to what is not, although it appears in Spain, being there the intellectual origin of what was tragically coined as "anti-Spanish in Spain" (see also The Two Spains).

This conservatism was firmly opposed to the French occupation and maintained a reactionary, absolutist conception of royal power, framed within an anti-enlightenment and anti-liberal Spanish thought of authors such as Fernando de Ceballos, Lorenzo Hervás and Panduro and Francisco Alvarado. Even during the period of the Cádiz Cortes, he opposed not only the liberal tendencies but also the moderate conservatives, led in turn by Francisco Cea Bermúdez and Luis López Ballesteros,

In the period following the first restoration, the reactionary sector prevailed, implementing, for example, educational policies (General Study Plan of the Kingdom), which radically modified university teaching that had been updated during the liberal triennium and the brief Napoleonic influence, suppressing a good part of scientific studies in favor of Law and Theology.

After the restoration of the monarchy, the difference between reactionaries and moderates became evident and extreme in the dispute between the Carlists —generally seen as an expression of reactionary conservatism— and the supporters of Isabel II of Spain (see «reign» in that article), generally perceived as moderate. With the triumph of the supporters of the latter, moderate conservatism became an institutional political force through the "Moderate Party", under the government presidency of Francisco Martínez de la Rosa. This party finally joined with the Liberal Union to form the Liberal-Conservative Party, under the leadership of Cánovas del Castillo.

This conservatism (see "canovism") takes up some of the perceptions of the reactionary current, characterized by a distrust in the ability of the people to govern themselves, for which reason the political authority should be the monarchy. Therefore, it considers the popular vote and opinion useless. In addition, through the so-called "Orosio Decree" it returns to suspend academic freedom in Spain "if it violates the dogmas of faith", seeking to strengthen the integrist principle that made the nation a project sustained in the divine will. During this period, more moderate conservatism found expression in the Constitutional Party, under the leadership of such people as Francisco Serrano and Domínguez y Sagasta.

Both sectors reached an agreement for the distribution of power, which some call «moderantismo», which was expressed politically in a two-party system in which electoral fraud, supported by caciquismo, made alternation possible as a means of avoiding conflicts. After the death of Cánovas the system continued to function under the more moderate aegis of Antonio Maura y Montaner. However, and despite the regenerationist attempts of this politician, the deep moral corruption, allegedly the result of the political system, finally led to the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera.

A product of this intellectual crisis also originated a great debate about the Being of Spain that sought to elucidate the possible existence of a national character as a possible explanation of the Spanish failure to produce unity and internal cohesion, as expressed in the apparent greater national consensus of other "more successful" nations, such as the French or the German, raising the possibility of a Spanish exceptionalism.

During that dictatorship, the economic protectionism begun in the previous period continued, protectionism that, together with a vague corporatism that developed simultaneously with that of Fascist Italy, gave reason for the Spanish economy to be described as one of the most closed from the world It is during that dictatorship that some of the longest-running monopolies in Spain were founded: Telefónica in 1924 and CAMPSA, 1927, as well as a public works policy (reservoirs, roads) that was continued by the Second Republic.

Subsequently, political life in Spain entered a new period of disruptions and deep confrontations, during the turbulent years of the Second Republic. During this period, it is necessary to highlight the role played in the consolidation of conservative thought by the magazine and cultural society Acción Española, founded by Ramiro de Maeztu in 1931, through which the best pens of the rich and varied conservative thought of the time paraded; men of the stature of José Calvo Sotelo, Víctor Pradera, José María Pemán, Rafael Sánchez Mazas, Jorge Vigón or Ernesto Giménez Caballero among many others. This publication served as a platform for the conservative sector to publicize its opposition not only to the republic but also its proposal for Hispanicity as a project to defend a profoundly Catholic and traditionalist conception of the culture of Spanish-speaking peoples.

During that time the Spanish Falange also emerged, which many consider an expression of the extreme right or fascist.

The aforementioned tensions ultimately resulted in the Spanish Civil War and appear to have only been resolved with the end of the dictatorship of Francisco Franco.

During and after the transition to democracy, a new political perception is present, which can be seen as surpassing the concentration on Hispanicity understood as separate or opposed to modern European thought: «Europeism» would end for becoming an essential unifying factor in the opposition to Francoism, uniting practically the entire Spanish political spectrum, including important figures from the Francoist elite, around the project for the integration of Spain into Europe." During the same period, two Characters have stood out as representatives of the evolution of Spanish conservatism: Gonzalo Fernández de la Mora in the tougher area and Joaquín Calomarde in the more moderate one.

Latin America

Conservatism in Latin America, alien to European monarchist traditions —with the exception of Mexico and Brazil, which did experience a monarchy— manifests itself as an attempt to maintain order —republican— emerging from the wars of independence. To begin with, this project lacked its own political ideology, similar to those that existed in Europe, thus expressing itself in two central elements: the maintenance of the existing social order (class system, etc.), which quickly turned into a struggle for the maintenance of the role of the Catholic Church and the maintenance of the legal order inherited from the colonial system.

The struggle for the primacy of the Catholic Church takes place against the backdrop of liberal attempts to remove that institution from the central role it had played during colonial times as the sole source of regulation and social legitimation. Thus, for example, during colonial times, to access higher education, it was necessary to pass a "purity of blood" test, that is, to demonstrate that one came from pure Hispanic families. The church, controlling the system of marriage, baptism, etc., controlled, in effect, who had access to such benefits. During the period after those wars, the Catholic Church was perceived by the conservative sector not only as a source of social stability, but also as providing a stable foundation for the "folk traditions" of the new nations, replacing the traditions of conquered indigenous peoples.

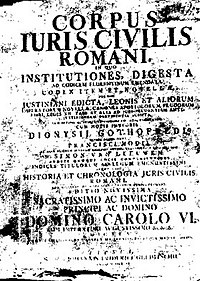

The legal body of colonial times —and, consequently, its members— were strongly influenced by concepts of late Roman Law, specifically, the code of Justinian I as commented on by Vinnius and the compilation of Roman Law of the medieval theologian Heineccius. These legal texts, together with the Siete Partidas, constituted the bases of the legal system that continued to be implemented after independence and gave a particularly "absolutist" vision, typical of an Empire of the time, of the principles and legal interpretations (see Corpus Iuris Civilis). Consequently, the proposal to restore the Hispanic legal order became, in practice, an eminently conservative proposal.

We find an example of this type of conservatism in José Rafael Carrera, who unified much of Central America around a proposal that basically consisted of the restoration of the socio-legal system of the colony, including rights and prerogatives (including fueros; control of education, etc.) ecclesiastical while in Mexico Agustín de Iturbide even changed sides, becoming an independentista -during and due to the Liberal Triennium in Spain- in order to maintain the primacy of traditional institutions, implementing a constitutional monarchy and exclusively Catholic (which only lasted two years).

However, by those dates a different type of conservatism had already begun to appear, one that sought to strengthen the nascent nation-states -with characteristics that at that time were called "capitalist", that is, the centralization of the economic and political systems under the control of elites in the capital cities of each country. This phenomenon occurred especially in the south of the continent. The origin of these nationalisms -which was expressed, influenced by romantic conceptions, in the "love of the land" or "love of the homeland" unlike the Burkean patriotic sense, based on the love for common rights and liberties or the Bismarkian, of unity based on a common language and culture - have been the subject of much discussion. The reason why Latin American patriotism did not express itself in the Bolivarian attempts or those of others in the sense of a Great Homeland has been, until now, the subject of debate.

Thus, conservatism came to have different expressions in different countries. While the vast majority were Republicans, in Mexico Agustín de Iturbide sought a constitutional and exclusively Catholic monarchy. Among the supporters of a republic, some, such as Juan Manuel de Rosas in Argentina, advocated a federal system, while in Chile Diego Portales sought a unitary state. Despite the fact that some conservatives —such as Manuel Oribe in Uruguay— and Portales himself were modernizers, others, for example in Venezuela —under the leadership of José Antonio Páez— even sought to maintain slavery. Both Rosas and Portales proposed order and defense of legality, but they were clearly willing to violate it when it suited them, while in Colombia José Eusebio Caro stated: "The conservative condemns any act against the constitutional order, legality, morality, freedom, equality, tolerance, property, safety, and civilization."

After this initial period, conservatism acquired a properly ideological content with positivism, especially the ideas of Auguste Comte: «the Comtian theory of order and progress establishes in Latin American positivism a clear adoption of the principle of subordination and segregation, where races and social classes as well as political predominance based on the possession of intellectual and moral knowledge could establish power". These positive ideas are modified, by characters such as José Victorino Lastarria, towards a version in which progress —in the sense that Comte uses, of improvement of the human condition— ceases to be the element that society must promote in order to maintain or achieve order (»... and progress, advancement, improvement of society, are not and cannot be political ends of the state".) in one in which order emanates from the institutions established in order to maintain "freedom": "freedom is no other thing that the use of law as we Americans practically understand it...", thus creating a basis for the synthesis of liberal and conservative thought that was observed towards the end of the century XIX and beginnings of the XX in the political thought of some Latin American countries.

Lastarria himself, alleging that under the concept of «freedom» all despotisms have been produced, separates the method (positivism) from its principles (freedom), so that the construction of the social is founded on the observation by the individual of legality, or more precisely, in a basically liberal proposal that perceives the citizen as a basic component of a civil society, "as a sovereignty of their own", interested in maintaining their freedom and not an individual as the last result of belonging to a society based on moral norms: "... order is a dependency on the institutions, at the mercy of obedience and love for society,...". However, and despite this modification "Lastarria thinks that in Latin America and, specifically in Chile, positivism is a new conservatism because it institutes a constructivist ideology over natural and spontaneous states, of which the historical reality of the continent shows a rich proliferation feration, these forms of social organization reproduced from European models are all products of the last stage of the metaphysical stage of history." This can be understood as meaning that both liberals and conservatives can unite around acceptance of the "positivist" role of religion (see Comte on this) and a conception of the state not as promoting progress but involved in the maintenance of order and national construction (See also Dictatorships of order and progress, and note that not all politicians mentioned in that article considered themselves "conservatives" in the context of the liberal-conservative struggles of the time) in order to defend or promote both what is perceived as the national interest and freedom (understood as the application of the existing law) and political-social stability.

In countries where that synthesis was not achieved—for example, Colombia—conflicts between liberals and conservatives continued throughout the century. XX —where they reached their peak in the period known as La Violencia— and it has even been suggested that they make their effects felt in the present in that country. Laureano Gómez —president of Colombia in the 1950s— is considered an example of this type of conservatism in that period.

The other notable influence on Latin American conservatism of that time was that of Herbert Spencer, creator of social Darwinism, and whose ideas bordered on racism. Nothing, including humanitarian tendencies, should interfere with Spencer's "natural laws," which mean that the "fittest" survive and the rest perish. However, despite the name of his ideas, Spencer did not accept Darwin's theory, proposing a version of Lamarquismo, according to which the "organs" develop by use (or degenerate due to lack of use) and those Changes are passed from one generation to the next. For Spencer, society is also an organism, wrapping towards more complex forms according to the "law of life", that is, according to the principle of the survival of the fittest, both at the individual level and as societies (what was interpreted by many in Latin America as sanctioning the marginalization of the "Indians", who, even these days, are considered inferior by some). Consequently, Spencer was opposed—radically—to all manifestations of "socialism," such as generalized or compulsory public education, public libraries, industrial safety laws, and, in general, any legislation or social project. This position -which reconstructed and reaffirmed the already mentioned prejudice of "cleanliness of blood" -contributing to an ideology of superiority and virtue to those who possessed such supposed "cleanliness" thus justifying suggestions such as those of José Manuel Pando, who held "that the Indians are inferior beings and their elimination is not a crime but a natural selection" or those of Bautista Saavedra, for whom "the Indian is just a beast of burden, miserable for whom one should not have compassion and to whom there is explode to the point of inhumane and shameful."

Brazil

Main article: Conservatism in Brazil

Most traditional Brazilian conservative views include a belief in political federalism, Catholicism, and monarchism. The current president, Jair Bolsonaro, is a conservative. Olavo de Carvalho stood out in the country as the ideological guru of Bolsonaro.

Conservatism Today

Since several national variants arose and in turn other combinations with other ideals, the best way to distinguish conservatism today is by observing what are the premises of these political ideals, which have influences in many places today.

European conservatism

It can be argued that at the beginning of the XXI century the more reactionary tendencies of conservatism —represented by various legitimist or far-right or even ultramontane - have ceased to have relevant political influence in European political life except indirectly (thus, for example, the NPD (National Democratic Party of Germany) achieves around 9% of the vote in the state of Saxony and the DVU (German People's Union), (approximately 6% in Brandenburg)

Similarly, traditional nationalist movements—including parties that were until recently "regionalist" (such as Fianna Fáil in Ireland) and those that still are (such as the League in Italy)—have less political weight at the European level (see, for example, Independence and Democracy and Union for Europe of Nations), with a grand total of 66 MEPs out of a total of 777. It should also be noted that in the group For Europe of Nations, Fianna Fáil, considered the senior partner, is described as both nationalist and centrist and, as such, could easily have been in the "liberal-democrat regionalist" or ALDE (Liberal Democratic Alliance for Europe) group with which he sits on the Council of Europe.

The more moderate tendencies are represented by a variety of parties that are grouped at the European level into the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) and the European Democrats. This sector is the group with the largest number of seats (268) in the European Parliament and is the one that brings together the currents derived from both modern continental European conservatism —exemplified in the Christian Democratic parties— and those influenced by Anglo-Saxon or Burkean conservatism.

What unites these tendencies is a respect for a traditional conception of democracy, civil rights and duties and other institutions derived from them in the European states as they are constituted. The same can be said in relation to private property and the "relatively" free market.

Politically, there is a tension between a Euro-unifying wing (represented by the so-called Franco-German axis (see Franco-German Relations and the Schuman Declaration) and the more nationalist or Eurosceptic wing, represented by English conservatism (see Movement for Reform Europe), which has led (2009) to the division of the conservative group, with the appearance of a new "anti-federalist" or "Eurosceptic" group. For some, this Group of European Conservatives and Reformists represents the decantation of policies that border not in conservatism but in extremism, or of constituting a group that suffers from internal contradictions

In the economy, European conservatives are divided between those who suggest an interventionist model —along with dirigisme or the social state— and those who support an absolutely free market.

The latter position is, in general, a novelty in European conservatism, and was introduced by former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. Some commentators have questioned whether her view is consistent with the traditional view of British conservatism, being more related to that of classical liberalism. Thatcher was described as "a radical in the Conservative party" and her ideology as threatening "established institutions" and "accepted elite beliefs", positions that some see as incompatible with traditional conservatism. However, "the privatization of state-owned industries, previously unthinkable, has become common and is now imitated throughout the world" (op. cit.)

In the social field, current European conservatism deliberates on the positions raised especially by social liberalism, in relation to which, notwithstanding its clear definition in favor of the primacy of moral principles as the cohesive substratum of a society, there is a certain variation, in that not all conservatives seek to maintain or impose in an "exclusive" way traditional moral conceptions. Thus, for example, in the debate about same-sex marriage, some perceive such legalization as the extension of the benefits of participation in social institutions to sectors that were traditionally excluded, a situation that can only increase social cohesion —a perception supported by a evolution in the religious positions themselves, towards a greater acceptance of the rights of homosexuals to participate and fully benefit from their religious and civic membership. Additionally, in this area, a decline can be observed in the positions that seek to grant to the religions (whether Christian or other) a unique role—as opposed to a primary one—in defining public morality or ethics.

Traditional conservatism

This type of conservatism is born from the opposition to the conservative variants that arose when merging with other ideals. This type of conservatives especially defend tradition and culture. Among his ideals we can highlight the defense of the conservative legacy, the defense of religion and traditional education systems.

Traditional conservatism in turn defends its ideologues and its history, they are opposed to all kinds of unnecessary war as these are considered, methods that destroy the organization and end up damaging both society and the church and family traditions that carry with them the culture of a nation.

In turn, this type of conservatism sees how political illusions have been the ones that have most destroyed the ideals that planned to form prosperous and stable cultures. This comes from the great massacres both communists and totalitarianism, which also encourages his ideal of opposing any genocide. This conservatism thinks that democracy is the best system for the defense of the individual and therefore should not fight for other destructive systems of order and freedom.

Nationalist conservatism

Nationalist conservatism arose from political processes that tended towards radical protectionism. These movements arise all over the world, especially in Europe, although there are also cases in Latin America. Many of these conservatives consider themselves to be the true ones since they support the homeland before any other alternative and they apply to their ideals premises that support the nationalist spirit.

This type of conservatism especially respects the value of the individual in society and firmly believes that he has to forge part of society so that nationalist ideals can be fulfilled. Normally these conservatives also believe in the borders of countries as a fundamental model for the creation of culture.

Liberal conservatism

Unlike nationalist conservatives, this type of conservative supports free trade measures, but continues to attach fundamental importance to economic privatization. At the same time, other conservative thoughts continue to be maintained, in this ideal.

The post-modern era has exposed some of the most important dichotomies between conservatism and liberalism. the idea of indefinite economic progress can collide with the preservation of fundamental cultural values of a nation. Indeed, the individualism proposed by liberalism can be a factor of social rupture. The conservative-liberals are in favor of supporting technological processes, and industrial development, in their economic measures.

Contenido relacionado

Vladimir Putin

Chilean presidential election of 1952

Anibal Acevedo Vila