Cleopatra

Cleopatra VII Thea Philopator —in ancient Greek: Κλεοπᾰ́τρᾱ Φιλοπάτωρ, romanized: Kleopátrā Philopátōr— (69 BC-10 or 12 August 30 BC), known as Cleopatra, was the last ruler of the Ptolemaic dynasty of Ancient Egypt, although nominally she succeeded her as pharaoh her son Caesarion. She was also a diplomat, naval commander, linguist, and writer of medical treatises. She was a descendant of Ptolemy I Soter, founder of the dynasty, a Greco-Macedonian general of Alexander the Great. After Cleopatra's death, Egypt became a province of the Roman Empire, marking the end of the Hellenistic period that had begun with the reign of Alexander (336-323 BC). C.). Her mother tongue was Koine Greek, although she was the first Ptolemaic sovereign to learn the Egyptian language.

In 58 B.C. C. presumably accompanied his father, Ptolemy XII, during his exile in Rome after a revolt in Egypt, which allowed his older sister, Berenice IV, to claim the throne; she is she was killed in 55 B.C. C. when her father returned to Egypt with Roman military assistance. When Ptolemy died in 51 B.C. C. , Cleopatra and her little brother, Ptolemy XIII, acceded to the throne as co-regents but the break between them unleashed a civil war.

After the defeat suffered in 48 a. In the battle of Pharsalus by his rival Julius Caesar during the second Roman civil war, the Roman statesman Pompey the Great fled to Egypt, a client state of Rome. Ptolemy XIII ordered the assassination of Pompey while Caesar occupied Alexandria in pursuit of his enemy. As consul of the Roman Republic, Caesar tried to reconcile Ptolemy XIII with his sister Cleopatra, but Pothinus the Eunuch, chief adviser to the Egyptian monarch, believed that the consul's proposed terms benefited his sister and so his forces besieged Caesar. and Cleopatra in Alexandria. The siege was lifted by the arrival of Caesar's allies in early 47 BC. C. and Ptolemy XIII died shortly after in the battle of the Nile. Arsinoe IV, Cleopatra's younger sister who had led the siege, went into exile in Ephesus and Caesar, then elected dictator, declared Cleopatra and her little brother Ptolemy XIV co-rulers of Egypt. However, the Roman general began a sentimental relationship with the Egyptian queen from whom Caesarion, the future Ptolemy XV, was born. Cleopatra traveled to Rome in 46 and 44 B.C. C. as a vassal queen and stayed in Caesar's villa. When he was assassinated in 44 B.C. C. , Cleopatra tried to have her son designated heir, but could not due to the rise to power of Octavian (later known as Augustus and who would be the first emperor of Rome in 27 BC ). Cleopatra then ordered the assassination of her brother Ptolemy XIV and elevated her son Caesarion as co-regent of Egypt.

During the third civil war of the Roman Republic (43-42 BC), Cleopatra allied herself with the Second Triumvirate, formed by Octavian, Mark Antony and Lepidus. Upon meeting her on Tarsus in 41 BC. C., the Egyptian ruler began a relationship with Marco Antonio from which three children were born: Alexander Helios, Cleopatra Selene II and Ptolemy Philadelphus. Antony used his authority as a triumvir to execute Arsinoe IV, fulfilling Cleopatra's wish. He increasingly relied on the Egyptian queen for both funding and military aid during his invasions of the Parthian Empire and the Kingdom of Armenia. In the Donations of Alexandria, Cleopatra's children with Mark Antony were appointed rulers over various territories under Antony's authority. This fact, together with the marriage of Marco Antonio with Cleopatra after his divorce from Octavia the Minor, Octavio's sister, unleashed the fourth civil war of the Roman Republic. After engaging in a propaganda war, Octavian forced Antony's allies in the Roman Senate to flee and declared war on Cleopatra in 32 BC. C. Mark Antony's and Cleopatra's war fleet was defeated by Octavian's, under the command of their general Agrippa, at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC.. The victorious Roman troops invaded Egypt in 30 BC. C. and they defeated Antonio's, after which he committed suicide. When Cleopatra learned that Octavian intended to take her to Rome to display her in a triumphal procession, she too committed suicide, something popularly believed to have been done by letting herself be bitten by a poisonous snake.

Cleopatra's legacy lives on in numerous works of art, both ancient and modern, and numerous dramatizations of her life in literature and other media. Several works of Roman historiography and Latin poetry portray the queen of Egypt, the latter generally giving a negative and polemical view of the likeness of her that survived in medieval and Renaissance literature. The visual arts of antiquity depicted Cleopatra on Roman and Ptolemaic coins, sculptures, busts, reliefs, glass vases, cameos, and paintings. It was the subject of many works of Renaissance and Baroque art, including sculptures, paintings, poems, and plays such as William Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra (1608), and operas such as Julius Caesar in Egypt. (1724), by Handel. In recent times, Cleopatra has appeared in both fine and applied arts, in burlesque satires, in Hollywood movies such as Cleopatra (1963) played by Elizabeth Taylor, or as a trademark image, for which since the XIX century is an icon of «Egyptomania».

Etymology

The Latin form of Cleopatra comes from the ancient Greek Kleopátrā (Greek: Κλεοπᾰ́τρᾱ), meaning "glory of her father" in the form feminine. This is derived from kléos (κλέος) 'glory' and patḗr (πᾰτήρ) 'father', using the genitive patros (πατρός). The masculine form would have been written as Kleópatros (Κλεόπᾰτρος) or Pátroklos (Πάτροκλος). Cleopatra Alcyone, wife of Meleager in Greek mythology. Through the marriage of Ptolemy V Epiphanes and Cleopatra I Sira (a Seleucid princess), the name was introduced into the Ptolemaic dynasty. Cleopatra's adopted title Theā́ Philopátōra (Θεᾱ́ Φιλοπάτωρα) means "goddess who loves her father". As for the accentuation, the bibliography in Spanish uses the forms Filopator, Filópator and Filopátor, opting throughout this article for the The latter, according to the transcription into Spanish of the Greek proper names in Galiano (1969, p. 81).

Biography

Historical context

The Ptolemaic pharaohs were crowned by the high priest of Ptah in Memphis, Egypt, but resided in the multicultural and largely Greek city of Alexandria, established by Alexander the Great of Macedonia. They spoke Greek and ruled Egypt as Hellenistic Greek monarchs, refusing to learn the native Egyptian language. By contrast, Cleopatra could speak several languages before reaching adulthood and was the first Ptolemaic ruler to learn the Egyptian language. She also spoke Ethiopian, Troglodyte, Hebrew (or Aramaic), Arabic, Syrian (perhaps Syriac), Median, Parthian, and Latin, though her Roman contemporaries might have preferred to speak to her in her native Koine Greek. Her knowledge of all of these Languages also reflected Cleopatra's desire to restore the territories in North Africa and West Asia that had once belonged to the Ptolemaic Kingdom.

Roman interventionism in Egypt preceded the reign of Cleopatra. When Ptolemy IX Latyrus died in late 81 B.C. He was succeeded by his daughter Berenice III. However, with opposition at the royal court to the idea of a reigning female monarch, Berenice III agreed to joint rule and marriage to her cousin and stepson Ptolemy XI Alexander II, an arrangement imposed by the Roman dictator Sulla. Ptolemy XI had his wife killed shortly after their marriage in 80 BC. , but was lynched in the resulting riots in Alexandria when news of the assassination broke. as collateral for loans, so the Romans had legal grounds to seize Egypt, their client state, after the assassination of Ptolemy XI. Instead, the Romans preferred to divide the Ptolemaic kingdom among the illegitimate children of Ptolemy IX, granting Cyprus to Ptolemy of Cyprus and Egypt to Ptolemy XII Auletes.

Early Years

Cleopatra was born in early 69 B.C. from the union of the reigning pharaoh Ptolemy XII and an unknown mother, possibly Ptolemy XII's wife Cleopatra VI Tryphena (also known as Cleopatra V), mother of Cleopatra's older sister Berenice IV Epiphene. Cleopatra Tryphena disappears from official records a few months after Cleopatra's birth in 69 BC. C. The three youngest children of Ptolemy XII, Cleopatra's sister, Arsinoe IV, and the brothers Ptolemy XIII Teos Filopátor and Ptolemy XIV, were born in the absence of his wife. The tutor of Cleopatra's childhood was Philostratus, from whom she learned the arts of oratory and Greek philosophy. During her youth, she presumably studied at the Museion (which included the Library of Alexandria).

Reign and exile of Ptolemy XII

In 65 B.C. C. the Roman censor Marcus Licinius Crassus argued before the Roman Senate that Rome should annex Ptolemaic Egypt, but his bill and a similar one by the tribune Servilius Rulo in 63 a. C. were rejected. Ptolemy XII responded to the threat of possible annexation by offering remunerations and generous gifts to powerful Roman statesmen, such as Pompey during his campaign against Mithridates VI of Pontus, or Julius Caesar after his election as Roman consul in 59 BC. C. Ptolemy XII's wasteful behavior bankrupted him and he was forced to obtain loans from the Roman banker Gaius Rabirius Posthumus.

In the year 58 B.C. C. the Romans annexed Cyprus to their empire and, under accusations of piracy, Ptolemy of Cyprus, brother of Ptolemy XII, decided to commit suicide rather than go into exile in Paphos. Ptolemy XII remained publicly silent about the death of his brother, a decision which, along with ceding traditional Ptolemaic territory to the Romans, damaged his credibility among subjects already enraged by his economic policies. Ptolemy XII, either by force or voluntary, exiled himself from Egypt by traveling first to Rhodes, then to Athens, and finally to the villa of Pompey the triumvirate in the Albanos Hills near Palestrina, Italy, where he spent nearly a year outside Rome, apparently accompanied by his daughter Cleopatra, who she was about 11 years old at the time. Berenice IV sent an embassy to Rome to defend her rule and oppose the reinstatement of her father Ptolemy XII, but Ptolemy assassinated the embassy leaders, an incident that was covered up by his powerful Roman supporters. When the Roman Senate denied Ptolemy XII his request for an armed escort and supplies for his return to Egypt, he decided to leave Rome in late 57 BC. C. and reside in the Temple of Artemis in Ephesus.

Ptolemy XII's Roman financiers remained determined to restore him to power. Pompey persuaded Aulus Gabinius, the Roman governor of Syria, to invade Egypt and restore Ptolemy XII, offering him 10,000 talents for this mission. placed it outside Roman law, Gabinius invaded Egypt in the spring of 55 BC. C. through Hasmonean Judea, where Hyrcanus II had Antipater of Idumea, father of Herod I the Great, to supply the army led by the Romans. At that time a young cavalry officer, Marco Antonio he was under the orders of Gabinius; she distinguished herself by preventing Ptolemy XII from massacring the inhabitants of Pelusium and by rescuing the body of Archelaus, Berenice IV's husband, after he had been killed in battle, ensuring him a proper royal burial. Cleopatra, now 14 years old old, had traveled with the Roman expedition to Egypt; Years later, Antonio would declare that he had fallen in love with her at this time.

Gabinius was put on trial in Rome for abusing his authority, although he was acquitted, but a second trial for taking bribes sentenced him to exile, from which he was reinstated by Caesar seven years later in 48 a. Crassus replaced him as governor of Syria and extended provincial rule from him to Egypt, but he was killed by the Parthians at the Battle of Carras in 53 BC. C. Ptolemy XII had Berenice IV and her wealthy supporters executed, seizing their property. He allowed the Gabiniani, Gabinius' Roman garrison made up largely of Germans and Gauls, harassed the population in the streets of Alexandria and installed his Roman banker Rabirius as his finance officer. A year later Rabirius was placed in protective custody and sent to Rome when he saw that his life was in danger for depleting resources in Egypt. Despite these problems, Ptolemy XII wrote a will designating Cleopatra and Ptolemy XIII as his joint heirs, oversaw major construction projects such as the Temple of Edfu and a temple at Dendera, and stabilized the economy. On May 31, 52 B.C. C. Cleopatra was appointed regent for Ptolemy XII, as indicated by an inscription in the Temple of Hathor at Dendera. Rabirius was unable to collect the entire debt of Ptolemy XII at the time of his death, for what happened to his successors Cleopatra and Ptolemy XIII.

Ascension to the throne

Right: The cartridges of Cleopatra and Cesarion in a limestone trail of the high priest of Ptah in Egypt, dated from the ptolemaic period, exposed at the Petrie Museum.

Ptolemy XII died sometime before March 22, 51 B.C. C., when Cleopatra, in her first act as queen, began her journey to Hermontis, near Thebes, due to the discovery of a new Bujis, a sacred bull worshiped as an intermediary of the god Montu in the religion of Ancient Egypt. Cleopatra had to deal with several pressing problems and emergencies soon after ascending the throne, such as famine caused by drought and a low level of the annual flooding of the Nile and the lawless behavior of the Gabiniani, the soldiers from Gabinius's garrison left behind in Egypt, now unemployed and assimilated as Romans. Heir to her father's debts, Cleopatra also owed the Roman Republic 17.5 million drachmas.

In 50 B.C. C. Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus, proconsul of Syria, sent his two eldest sons to Egypt, most likely to negotiate with the Gabiniani and recruit them as soldiers in the desperate defense of Syria against the Parthians However the Gabiniani tortured and murdered both, perhaps secretly encouraged by the disloyal top administrators of Cleopatra's court. Cleopatra sent Bibulus to the Gabiniani i> guilty as prisoners awaiting their trial, but he sent them back and reprimanded her for interfering in his trial, stating that it was the prerogative of the Roman Senate. Bibulus, Pompey's ally in the republic's civil war, could not prevent them from Caesar procured a naval fleet in Greece, which eventually allowed it to reach Egypt in pursuit of Pompey, hastening Caesar's eventual victory.

On August 29 of the year 51 B.C. , official Egyptian documents began to list Cleopatra as sole ruler, evidence that she had rejected her brother Ptolemy XIII as co-regent. She had probably married him, according to custom, but there is no record of this. The Ptolemaic practice of sibling marriage was introduced by Ptolemy II and his sister Arsinoe II, an ancient Egyptian practice that was abhorred by their Greek contemporaries. At the time of Cleopatra's reign, it was considered a normal arrangement among Ptolemaic rulers.

Despite Cleopatra's rejection, Ptolemy XIII still retained powerful allies, notably the eunuch Pothinus, his childhood tutor, regent, and administrator of his estates, as well as Aquilas, a prominent military commander, and Theodotus of Chios, another of her tutors. Cleopatra appears to have attempted a short-lived alliance with her brother Ptolemy XIV, but in the fall of 50 BC. C. , Ptolemy XIII got the upper hand in their conflict and began signing documents with his name before his sister's, followed by setting his first regnal date in the 49 a. C.

Assassination of Pompey

In the summer of 49 B.C. , Cleopatra and her troops were still fighting Ptolemy XIII in Alexandria, when Pompey's son Gnaeus Pompey arrived seeking military aid for his father. After returning to Italy from the wars in Gaul and crossing the Rubicon in January 49 BC. , Caesar had forced Pompey and his followers to flee to Greece. In what was perhaps their last joint decree, both Cleopatra and Ptolemy XIII agreed to Gnaeus Pompey's request and sent his father 60 ships and 500 troops, including the Gabiniani, an action that helped erase part of the debt owed to Rome. Losing the fight against her brother, Cleopatra was forced to flee Alexandria and retreat to Thebes region. In the spring of 48 B.C. C. traveled to Roman Syria with his little sister, Arsinoe IV, to assemble an invasion force to head for Egypt. He returned with an army, but his advance towards Alexandria was blocked by the forces of his brother, including some Gabiniani mobilized to fight her, so she camped outside Pelusio, in the eastern Nile delta. In Greece, the forces of Caesar and Pompey met in the decisive Battle of Pharsalus on August 9, 48 BC. C., which caused the destruction of most of Pompey's army and his forced flight to Tyre. Given his close relationship with the Ptolemies, Pompey finally decided to take refuge in Egypt, where he could replenish his forces. However, Ptolemy XIII's advisers feared the possibility that Pompey would use Egypt as a base in a protracted Roman civil war. In a conspiracy devised by Ptolemy's adviser Theodotus, Pompey arrived by ship near Pelusio after being invited by written message, only to be ambushed and stabbed to death on September 28, 48 BC. C. Ptolemy XIII believed that he had thus demonstrated his power and at the same time reduced the tension by having Pompey's head, severed and embalmed, sent to Caesar, who arrived in Alexandria in early October. and settled in the royal palace. Caesar showed grief and indignation at Pompey's murder and asked Ptolemy XIII and Cleopatra to disband their forces and reconcile.

Relationship with Julius Caesar

Ptolemy XIII arrived at Alexandria at the head of his army, in clear defiance of Caesar's demand that he disband and abandon his army before his arrival. Cleopatra sent emissaries to Caesar, who supposedly told him that he was prone to have adventures with royal women. She eventually decided to go to Alexandria to see him in person. The Roman historian Cassius Dio indicates that she did so without informing her brother, dressed to look as beautiful as possible, and captivated him with her wit. The Greek historian Plutarch provides an entirely different and perhaps fancied account that claims she was wrapped in a sleeping bag to sneak into the palace and meet Caesar.

When Ptolemy XIII learned that his sister was in the palace to ally with Caesar, he tried to raise the population of Alexandria in a riot, but was arrested by Caesar, who used his oratorical skills to calm the frenzied crowd. He subsequently brought Cleopatra and Ptolemy XIII before the Council of Alexandria, where Caesar revealed the written testament of Ptolemy XII—previously held by Pompey—naming Cleopatra and Ptolemy XIII as his co-heirs. Caesar later tried to reach an agreement so that the other two brothers, Arsinoe IV and Ptolemy XIV, would rule Cyprus together, thus eliminating potential rivals claiming the Egyptian throne while appeasing Ptolemaic subjects still embittered by the loss of Cyprus to the Romans in 58 a. C.

Considering that this arrangement favored Cleopatra over Ptolemy XIII and that the latter's 20,000-strong army, including the Gabiniani, could defeat Caesar's 4,000-strong army without support, Pothinus he decided that Aquilas would lead his forces into Alexandria to attack Caesar and Cleopatra. The siege of the palace kept Caesar and Cleopatra trapped inside until the following year, the 47 a.m. C. When Caesar took Pothinus prisoner and executed him, Arsinoe IV joined forces with Aquilas and was declared queen; soon after her her tutor Ganymede killed Aquilas and took his place as commander of his army, then Ganymede tricked Caesar by requesting the presence of the captive Ptolemy XIII as a negotiator, only for him to join Arsinoe's army IV.

Sometime between January and March of 47 B.C. C. Caesar's reinforcements arrived, including those commanded by Mithridates of Pergamum and Antipater of Idumea. Ptolemy and Arsinoe withdrew their forces to the Nile, where Caesar attacked them. Ptolemy attempted to flee in a boat, but it capsized and drowned. Ganymede may have been killed in battle, Theodotus was found in Asia years later by Marcus Junius Brutus and executed, while Arsinoe was ostentatiously displayed at the triumph celebrated by Caesar in Rome before being exiled to the Temple of Artemis in Ephesus. Cleopatra was conspicuously absent from these events and remained in the palace, most likely because she had been pregnant with Caesar's child since September 47 a. C.

Caesar's term as consul had expired at the end of 48 BC. C. , but Antonio, one of his officers, helped get him elected as dictator that lasted a year, until October 47 BC. , giving Caesar legal authority to settle the dynastic dispute in Egypt. Trying to avoid making the mistake of Berenice IV, Cleopatra's sister, of having a single sovereign, Caesar appointed his brother from 12 years, Ptolemy XIV, as co-ruler to 22-year-old Cleopatra in a symbolic sibling marriage, but she continued to live privately with Caesar. The exact date Cyprus returned to her control is unknown, although she did have a governor there in the year 42 BC. C.

Caesar is believed to have taken a Nile cruise with Cleopatra to visit Egyptian monuments, though this may be a romantic account reflecting later trends in the Roman proletariat and not actual historical fact. The historian Suetonius He gave considerable detail about the voyage, including the use of the Thalamegos, the great pleasure craft built by Ptolemy IV, which during his reign measured 91m long and 24m high and was equipped with dining rooms, luxurious cabins, sacred shrines and walkways along its two decks, a veritable floating palace. Caesar might have been interested in the Nile cruise due to his fascination with geography; he was versed in the works of Eratosthenes and Pytheas and perhaps wanted to discover the source of the river, but returned before reaching Ethiopia.

Caesar left Egypt around April 47 B.C. , supposedly to confront Pharnaces II of Pontus, son of Mithridates VI, who was causing trouble for Rome in Anatolia. It is possible that Caesar, married to the prominent Roman lady Calpurnia, also wanted to avoid being seen together with Cleopatra when she gave birth to their son. He left three legions in Egypt, later increased to four, under the command of the freedman Rufius to secure Cleopatra's weak position, though perhaps also to keep her activities in check.

Caesarion, Cleopatra's son, potentially with Caesar, was born on June 23, 47 B.C. C. and was originally given the name "Pharaoh Caesar", as preserved on a stela in the serapeum at Memphis. Perhaps due to his still childless marriage to Calpurnia, Caesar kept public silence about from Caesarion (though perhaps she accepted his parentage in private). Cleopatra instead made repeated official statements about Caesarion's parentage, with Caesar as the father.

Cleopatra and her nominal co-ruler, Ptolemy XIV, visited Rome sometime in late 46 BC. , presumably without Caesarion, and given lodgings in Caesar's villa situated on the Horti Caesaris. Like their father Ptolemy XII, Cleopatra and Ptolemy XIV were granted legal status by Caesar of "friend and ally of the Roman people" (Latin: socius et amicus populi Romani), in fact, vassal rulers loyal to Rome. Among Cleopatra's visitors in Caesar's villa, across the Tiber, was held by Senator Cicero, who found it arrogant. Sosigenes of Alexandria, one of Cleopatra's court members, assisted Caesar in calculating the new Julian calendar, which entered in force throughout the Roman world on January 1 of the year 45 BC. The Temple of Venus Genetrix, built in the Forum of Caesar on September 25, 46 BC. , contained a gold statue of Cleopatra (where it remained until at least the III century AD..), directly associating the mother of Caesar's son with the goddess Venus, mother of the Romans; in a subtle way, the statue also linked the Egyptian goddess Isis with Roman religion. Caesar may have had plans to build a temple dedicated to Isis in Rome, as approved by the Senate a year after her death.

Cleopatra's presence in Rome most likely had consequences for the events of the Lupercalia held a month before Caesar's assassination; Antony attempted to place a royal diadem on Caesar's head, which Caesar rejected in what was probably a staged reenactment, perhaps to gauge the mood of the Roman public about accepting a Hellenistic-style monarchy. Cicero, who was present at the festival, mockingly asked where the diadem came from, an obvious reference to the queen. which he loathed. Caesar was assassinated on the Ides of March in 44 BC. , but Cleopatra remained in Rome until mid-April, in the vain hope that Caesarion would be recognized as Caesar's heir. However, in her will, she named her great-nephew Octavian as chief heir, who arrived in Italy at the same time that Cleopatra decided to leave for Egypt. A few months later, Cleopatra had Ptolemy XIV poisoned to death and proclaimed her son Caesarion co-regent.

Cleopatra in the civil war of the liberators

Octavian, Antony, and Lepidus formed the Second Triumvirate in 43 BC. C., in which they were elected for a period of five years to restore order in the Republic and bring to justice the assassins of Caesar (self-proclaimed the liberatores ). Cleopatra received messages from both Gaius Cassius Longinus, one of the assassins, and Publius Cornelius Dolabella, proconsul of Syria and Caesar's supporter, requesting military assistance. She decided to write to Cassius with an excuse that her kingdom was facing too many internal problems., while sending to Dolabella the four legions that Caesar had left in Egypt. However, these troops were captured by Cassius in Palestine. Meanwhile, Serapion, the strategos in Cleopatra's Cyprus, defected and joined Cassius and provided him with ships, so Cleopatra took her own fleet to Greece to personally assist Octavian and Mark Antony, but her ships were badly damaged in a Mediterranean storm and she arrived too late to take part in the fighting.. In the fall of 42 B.C. C., Mark Antony defeated the forces of Caesar's assassins at the Battle of Philippi in Greece, leading to the suicide of Cassius and Brutus.

At the end of 42 B.C. In the summer of 41 a. C., Mark Antony established his headquarters in Tarsus, Anatolia, and summoned Cleopatra in several letters, which she refused until Mark Antony's envoy Quintus Delius convinced her to come see him. The meeting would allow Cleopatra to clear up the misconception that she had supported Cassius during the civil war and to address territorial exchanges in the Levant, but Mark Antony was also undoubtedly wishing to establish a personal and romantic relationship with the queen. Cleopatra sailed up the Cydnos River to Tarsus on the Thalamegos, hosting Mark Antony and his officers for two nights with lavish banquets on board the ship. Cleopatra managed to clear her name as a supposed supporter of Cassio, arguing that he had really tried to help Dolabella in Syria. She also convinced Mark Antony to execute her sister Arsinoe IV, exiled in Ephesus, she was also handed over to the rebel strategos in Cleopatra's Cyprus for her execution.

Relationship with Marco Antonio

Cleopatra invited Mark Antony to come to Egypt before leaving Tarsus, prompting him to visit Alexandria in November 41 BC. C. He was well received by the people of Alexandria, both for his heroic actions during the restoration of Ptolemy XII to power and for arriving in Egypt without occupying forces as Caesar had done. In Egypt Antony he continued to enjoy the lavish regal lifestyle he had witnessed aboard Cleopatra's ship docked at Tarsus. He also had his subordinates, such as Publius Ventidius Bassus, drive the Parthians out of Anatolia and Syria.

Cleopatra handpicked Mark Antony as her partner to bear more heirs, as he was considered the most powerful Roman figure after Caesar's demise. With his powers as a triumvir, he also had broad authority to restore Caesar to him. Cleopatra formerly Ptolemaic lands, now in Roman hands. While it is clear that both Cilicia and Cyprus were under Cleopatra's control on November 19, 38 BC. , the transfer probably occurred earlier, in the winter of 41-40 BC. C. , during the time she spent with Marco Antonio.

In the spring of 40 B.C. C, Antony left Egypt due to problems in Syria, where its governor Lucius Decidius Saxa was assassinated and his army taken over by Quintus Labienus, a former officer of Cassius who now served the Parthian Empire. Cleopatra provided him with 200 ships for his campaign and as payment for his newly replenished territories. He would not see Mark Antony again for three years, but they corresponded and there are documents suggesting that he kept a spy in his camp. Towards the end of the year 40a. C., Cleopatra gave birth to twins, Alexander Helios and Cleopatra Selene II, whom Mark Antony recognized as his children. Helios (Greek: Ἥλιος) 'the sun' and Selene (Σελήνη) 'the moon', symbolized a new era of social rejuvenation, as well as an indication that Cleopatra expected Mark Antony to repeat the exploits of Alexander the Great by conquering to deliveries.

Mark Antony's Parthian campaign to the east was interrupted by the events of the Perusian War (41-40 BC), which began by his ambitious wife Fulvia against Octavian in the hope of making her husband the undisputed leader of Rome. It has been suggested that Fulvia wanted to separate Antony from Cleopatra, but the conflict had already started in Italy even before Cleopatra to meet Antony in Tarsus. Fulvia and Antony's brother Lucius were eventually besieged by Octavian in Perusia (present-day Perugia) and then exiled from Italy, after which she died in Sicyon in Greece while trying to reach Antony. Antony. His sudden death led to the reconciliation of Octavian and Antony at Brindisium (now Brindisi) in September 40 BC. ; although this agreement consolidated Antony's control over the territories of the Roman republic east of the Ionian Sea, it also stipulated that he cede Italy, Spain and Gaul and marry Octavian's sister Octavia the Minor, a potential rival to Cleopatra.

In December of 40 B.C. , Cleopatra welcomed Herod to Alexandria as an unexpected guest and refugee fleeing a turbulent situation in Judea. Mark Antony had established him there as tetrarch, but he soon fell out with Antigonus II Mattathias of the former Hasmonean dynasty, which had imprisoned Herod's brother and fellow tetrarch, Phasael, who was executed when Herod fled to Cleopatra's court. Cleopatra attempted to grant him a military assignment, but Herod refused and traveled to Rome, in where the triumvirs Octavian and Mark Antony made him king of Judea. This act put Herod on a collision course with Cleopatra, who wished to regain the former Ptolemaic territories that were part of her new kingdom.

Mark Antony's relationship with Cleopatra may have suffered when he not only married Octavia, but also had two children with her, Antonia the Elder in 39 BC. C. and Antonia the Lesser in the 36 a. , and moved his headquarters to Athens. Cleopatra's position in Egypt, however, was secure. Her rival Herod was busy with a civil war in Judea that required considerable Roman military assistance, but not he received none from Cleopatra. Since Mark Antony's and Octavian's authority as triumvirs had expired on January 1, 37 BC. , Octavia arranged a meeting at Tarentum, where the triumvirate officially lasted until 33 BC. C. With two legions granted by Octavio and a thousand soldiers ceded by Octavia, Marco Antonio traveled to Antioch, where he made preparations for the war against the Parthians.

Mark Antony summoned Cleopatra to Antioch to discuss pressing matters, such as Herod's kingdom and financial support for his Parthian campaign. Cleopatra took her three-year-old twins to Antioch, where their father saw them for the first time. time and where they probably first received their nicknames Helios and Selene as part of Mark Antony's and Cleopatra's ambitious plans for the future. To stabilize the east, Mark Antony not only expanded Cleopatra's domain, but also established new ruling dynasties and client governments that would be loyal to him, though they would ultimately outlast him.

With this agreement Cleopatra gained important former Ptolemaic territories in the Mediterranean Levant, including almost all of Phoenicia (Lebanon) except Tire and Sidon, which remained in Roman hands. Ptolemais also received Akko (now Acre, Israel), a city that was established by Ptolemy II. Given its ancestral relations with the Seleucids, it was awarded the region of Coelesyria along the upper Orontes River. It was even awarded the surrounding region of Jericho in Palestine, but ceded this territory to Herod. At the expense of the Nabataean king Malicos I (a cousin of Herod), Cleopatra also received a portion of the Nabatean kingdom around the Gulf of Aqaba on the Red Sea, including Ailana (now Aqaba, Jordan). To the west she was granted Cyrene along the Libyan coast, as well as Itano and Olunte on Roman Crete. Although still administered by Roman officials, these territories enriched her kingdom and led her to declare the establishment of a new era by striking a double date on their coins in 36 B.C. C.

[[File:Antony with Octavian aureus.jpg|miniature|Roman aureus with the portraits of Mark Antony (left) and Octavian (right), cast in 41 BC. C. to celebrate the establishment of the Second Triumvirate by Octavian, Antony and Lepidus in 43 BC. C. Mark Antony's expansion of the Ptolemaic kingdom by giving up territories directly controlled by the Romans was exploited by his rival Octavian, who capitalized on public sentiment in Rome against strengthening a foreign queen at the expense of his Republic. promoted the version that Antony was neglecting his virtuous Roman wife Octavia, granting both her and Livia Drusilla, his own wife, extraordinary privileges of sacrosanctity. Some 50 years earlier, Cornelia, daughter of Scipio Africanus, had been the first Roman woman to have a living statue dedicated to her. She was now followed by Octavia and Livia, whose statues were probably erected in Caesar's forum to rival those of Cleopatra, erected by Caesar.

In 36 a. C., Cleopatra accompanied Mark Antony to the Euphrates on his journey to invade the Parthian Empire. She then returned to Egypt, perhaps due to her advanced pregnancy. In the summer of 36 a. C. she gave birth to Ptolemy Philadelphus, her second son with Marco Antonio.

Antony's campaign in Parthia in 36 B.C. C. became a complete debacle for various reasons, notably the betrayal of Artavasdes II of Armenia, who defected to the Parthian side. After losing some 30,000 men, more than Crassus at Carras (an indignity he had hoped to avenge), Antony finally reached Leukokome near Berite (present-day Beirut, Lebanon) in December, drinking to excess before Cleopatra arrived to supply funds and clothing for his battered troops. Antony wished to avoid the dangers of returning to Rome, so he traveled with Cleopatra to Alexandria to see their newborn son.

Alexandria Donations

[[File:011-Mark Antony, with Cleopatra VII -3.jpg|thumbnail|A denarius minted in 32 B.C. C.; on the obverse is a portrait of Cleopatra with a diadem, with the Latin inscription "CLEOPATRA[E REGINAE REGVM]FILIORVM REGVM", and on the reverse one of Mark Antony with the inscription "ANTONI ARMENIA DEVICTA".]] While Antony was preparing for another expedition against the Parthians in 35 B.C. C., this time directed against her ally Armenia, Octavia traveled to Athens with 2,000 soldiers supposedly in support of Antony, but most likely following a plan devised by Octavian to shame him for his military losses. Antony received these troops and told Octavia not to stray east of Athens while he and Cleopatra traveled together to Antioch, but only to then suddenly and inexplicably abandon the military campaign and return to Alexandria. When Octavia returned to Rome, Octavian presented his sister as Antony's wronged victim, though she refused to leave Antony's home. Octavian's confidence grew as he eliminated his rivals in the west, including Sextus Pompey and even Lepidus the King. third member of the triumvirate, who was placed under house arrest after rebelling against Octavian in Sicily.

Anthony sent Quintus Delius as ambassador to Artavasdes II of Armenia in 34 BC. C. to negotiate a possible marriage alliance between the daughter of the Armenian king and Alexander Helios, son of Antony and Cleopatra. Having rejected the proposal, Antony went with his army to Armenia, defeated his troops and He captured the king and the Armenian royal family and brought them to Alexandria, where Antony held a military parade in imitation of a Roman triumph, dressed as Dionysus and riding into the city in a chariot to deliver the royal prisoners to Cleopatra, who was sitting on the throne. a gold throne on a silver dais. The news of this event was widely criticized in Rome as being in bad taste and a perversion of ancient and traditional Roman rites and rituals for the enjoyment of an Egyptian queen and her subjects.

In an act held in the capital's gymnasium shortly after the celebrations, Cleopatra dressed as Isis and declared that she was "Queen of Kings" and her son Caesarion, "King of Kings", while Alexander Helios was declared king of Armenia, Media, and Parthia, and the two-year-old Ptolemy Philadelphus was declared king of Syria and Cilicia. Cleopatra Selene II received Crete and Cyrene. Antony and Cleopatra may have been married during this ceremony, but it is difficult to know for sure due to the controversial, contradictory, and fragmented nature of the primary sources. Antony sent a report to Rome requesting ratification of these territorial grants, today known as the Donations of Alexandria. Octavian wanted to release it for political purposes, but the two consuls, both Antony's supporters, censored it out of the public domain.

At the end of 34 B.C. , Antony and Octavian engaged in a bitter propaganda war that would last for years. Antony claimed that his rival had illegally deposed Lepidus from the triumvirate, keeping his troops and preventing him from recruiting troops in Italy, while Octavian accused Antony of illegally arresting the king of Armenia, marrying Cleopatra despite still being married to her sister Octavia, and wrongfully declaring Caesarion as Caesar's heir instead of Octavian. and rumors spread during this propaganda war have shaped the popular image of Cleopatra from the literature of the Augustan era to the various media of the modern era. Cleopatra was said to have brainwashed Mark Antony with witchcraft and sorcery and that it was as destructive to civilization as Homer's Helen of Troy. Horace's Satires include an account that Cleopatra once dissolved a pearl worth 2.5 million drachmas in vinegar just to win a bet at a dinner party. The accusation that Antony had stolen books from the Library of Pergamum to restock the Library of Alexandria turned out to be an admitted fabrication by Gaius Calvisius Sabinus.

Published in 2000, a papyrus document from 33 B.C. C., which was later reused for a mummy wrapping, contains Cleopatra's signature, probably written by an official authorized to sign for her. It has to do with certain Egyptian tax exemptions granted to Quintus Caecilius or Publius Canidius Crassus, a former Roman consul and Antony's confidant who commanded his land forces at Actium. A text with a different script at the bottom of the papyrus reads "be it done" or "so be it" —in ancient Greek: γινέσθωι, romanized: ginésthōi—, which was undoubtedly written in the queen's own handwriting, since it was a practice of the Ptolemaic dynasty to endorse documents to avoid forgeries. A great discovery, as the only known surviving royal autographs from antiquity are from the much less relevant Ptolemy X and Theodosius II.

Battle of Actium

In a speech before the Roman Senate on the first day of his appointment as consul on January 1, 33 B.C. , Octavian accused Antony of attempting to undermine Roman liberties and his territorial integrity as a slave to his eastern queen. Before Antony and Octavian's joint imperium expired on 31 December of the year 33 B.C. , Antony declared Caesarion as Julius Caesar's true heir in an attempt to weaken Octavian. On 1 January 32 BC. C. Gaius Sosius and Gnaeus Domicius Enobarbus, both supporters of Antony, were elected consuls. On February 1, 32 BC. C. Sosio delivered a fiery speech condemning Octavio, by then a private citizen with no public office, and enacted laws against him. During the next session of the Senate, Octavio entered the Senate with armed guards and made his own accusations against the consuls. Intimidated by this act, the consuls and more than 200 senators who still supported Antony fled Rome the next day to join him.

Antony and Cleopatra traveled to Ephesus together in 32 B.C. C., where she provided him with 200 of his 800 ships. Enobarbus, fearful that Octavian's propaganda campaign would be confirmed before the people, tried to persuade Antony to keep Cleopatra out of the picture. against Octavian. However, Publius Canidius Crassus argued that Cleopatra was financing the war effort and that he was a competent monarch. Cleopatra refused Antony's requests to return to Egypt, considering that blocking Octavian in Greece he could more easily defend Egypt. His insistence on participating in the battle for Greece led to the defections of notable Romans such as Aenobarbus and Lucius Munacio Plancus.

During the spring of 32 B.C. C. Antony and Cleopatra traveled to Samos and then to Athens, where she persuaded Antony to send Octavia an official declaration of divorce, prompting Plancus to advise Octavian to seize the will Antony, in the custody of the Vestals. Despite being a violation of sacred principles and legal rights, Octavian forcibly obtained the document from the Temple of Vesta, making it a powerful tool in his propaganda war against Antony and Cleopatra. Octavian revealed parts of his will, such as that Caesarion was named Caesar's heir, that the Donations of Alexandria were legal, that Antony was to be buried next to Cleopatra in Egypt instead of in Rome, or that Alexandria would become the new capital of the Roman Republic. As a show of loyalty to Rome, Octavian decided to begin construction of his own mausoleum on the Field of Mars. Octavian's legal position was also enhanced by his being elected consul in the 31 a. C. With Antony's will made public, Octavian already had his casus belli and Rome declared war on Cleopatra, not Antony. The legal argument for war it was based not so much on Cleopatra's territorial acquisitions, with the former Roman territories ruled by her sons with Antony, but rather on the fact that she was providing military support to a private citizen, now that Antony's triumviral authority had expired..

Antony and Cleopatra had a larger fleet than Octavian's, but their navy crews were poorly trained, some probably drawn from merchant ships, while Octavian had an entirely professional force. Antony wanted to cross the Adriatic Sea and stop Octavian in Tarentum or Brindisium, but Cleopatra, concerned above all with defending Egypt, opposed the decision to attack Italy directly. They established their winter headquarters in Patrai (Greece) and towards the spring of the 31 B.C. C. had moved to Actium, south of the Gulf of Ambracia.

Antony and Cleopatra had the support of several allied kings, but Cleopatra had already been in conflict with Herod and an earthquake in Judea provided her with an excuse not to engage her forces in the campaign. They also lost the support of Malicos I of Nabatea, which later proved to have strategic consequences. Antony and Cleopatra lost several skirmishes against Octavian around Actium during the summer of 31 BC. C. and there were continuous desertions to Octavian's camp, such as those of Antony's long-time companion Delius and the hitherto allied kings Amyntas of Galatia and Deiotarus of Paphlagonia. While some members of the Antony's army suggested abandoning the naval conflict to retreat inland, Cleopatra insisted on a naval confrontation, to keep Octavian's fleet away from Egypt.

On September 2, 31 B.C. C. Octavian's naval forces, led by Marco Vipsanio Agrippa, faced those of Antony and Cleopatra in the Battle of Actium. Cleopatra, aboard her flagship, the Antonias, was in the rear of the fleet commanding 60 ships at the mouth of the Gulf of Ambracia, in what was probably a ploy by Antony's officers to sideline it during the battle. Antony had ordered his ships to have sails on board for a better chance of pursuing or fleeing the enemy, which Cleopatra, always concerned with the defense of Egypt, used to move quickly through the main fighting zone in a strategic retreat to the Peloponnese. Stanley M. Burstein is of the opinion that pro-Rome writers later accused Cleopatra of having cowardly deserted Antony, but her original intention in keeping her sails on board may have been to break the blockade and save as much of her fleet as possible. Antony continued Cleopatra and boarded her ship, identified by its distinctive purple sails, as the two escaped the battle and headed for Tenaros. Antony is said to have avoided Cleopatra during this three-day voyage, until urged by her servant girls in Tenaros to talk to her. The Battle of Actium continued without Cleopatra and Antony until the morning of 3 September, with massive desertions of officers, troops, and kings allied to Octavian's army.

Fall and death

While Octavian occupied Athens, Antony and Cleopatra landed at Paraitonion in Egypt. The couple then set out on their separate journey, Antony to Cyrene to gather more troops, and Cleopatra sailing to the port of Alexandria in a deceitful attempt to show the operations in Greece as a victory. It is not certain if at this time she executed Artavasdes II and sent his head to her rival, Artavasdes I of Media Atropatene, in an attempt to establish an alliance with him.

Lucio Pinario, who was appointed governor of Cyrene by Mark Antony, received news of Octavian's victory before Antony's messengers arrived. Pinario had the messengers executed and then defected to Octavian's side, who handed over the four legions under his command that Mark Antony aspired to achieve. Antony was on the verge of committing suicide upon hearing the news, but his staff officers prevented it. In Alexandria he built a small isolated house on the island of Faro, which he named Timoneion, after the philosopher Timon of Athens, famous for his cynicism and misanthropy. Herod, who had personally advised Antony after the battle of Actium that he should betray Cleopatra, he traveled to Rhodes to meet Octavian and renounce his kingship out of loyalty to Antony. Impressed by her directness and sense of loyalty, Octavian allowed her to hold her position in Judea, further isolating Antony and Cleopatra. Perhaps Cleopatra began to see Antonio as a burden in the late summer of 31 BC. , when he was preparing to leave Egypt to his son Caesarion. He planned to cede his throne to him and move his fleet from the Mediterranean to the Red Sea and then sailing to a foreign port, perhaps in India, where he could spend a recuperating. However, these plans did not come to fruition when Malicos I, on the advice of Quintus Didius, Octavian's appointed governor of Syria, burned Cleopatra's fleet in revenge for their losses in an earlier war against Herod. largely by Cleopatra. Thus, he had no choice but to stay in Egypt and negotiate with Octavian. Although it was most likely information from Octavian's propaganda campaign, it was said that Cleopatra began testing the efficacy of various poisons on prisoners and even their own servants.

Cleopatra brought Caesarion into the ephebeia which, together with an inscription on a Coptos stele dated September 21, 31 BC,. , shows that he was grooming his son to become the sole ruler of Egypt. Antony also had Marco Antony Antilo, his son with Fulvia, enlist at the same time as an ephebe. Messages were sent to him by Separated Octavian, still stationed in Rhodes, though Octavian seems to have answered only to Cleopatra. She petitioned that her sons inherit Egypt and that Antony be allowed to live there in exile, offering Octavian money at a later date and sending him at once. lavish gifts. Octavian sent his diplomat Tirso to her when she threatened to burn herself and much of her treasure inside a large tomb already under construction. Tirso was to advise her to kill Antony so that he would spared his life, but when Antonio suspected his intentions, he had him whipped and sent him back without any agreement.

After lengthy negotiations that ultimately failed, Octavian set out to invade Egypt in the spring of 30 BC. , stopping at Ptolemaida in Phoenicia, where his new ally Herod provisioned his army. He headed south and soon took Pelusium, while Gaius Cornelius Gaul, marching east from Cyrene, defeated Antony's forces near Paraitonion. Octavian then advanced on Alexandria, but Antony returned and won a small victory over Octavian's exhausted troops just outside the city's hippodrome. 30 B.C. C. Antony's naval fleet surrendered, followed by his cavalry. Cleopatra hid in her tomb with her trusted attendants, sending a message to Antony that she had committed suicide. Desperate, Antony reacted to this situation by stabbing himself in the stomach and taking his own life, at the age of 53. According to Plutarch, he was still dying when he was carried to Cleopatra in her tomb, and told her that he had died honorably and that she could to trust Octavian's companion, Gaius Proculeius, before anyone else in his entourage. However, it was Proculeus who entered his tomb using a ladder and stopped the queen, depriving her of the possibility of burning herself with his treasures. Cleopatra was allowed to embalm and bury Antony inside his tomb before being escorted to the palace.

Octavian arrived in Alexandria, occupied the palace, and arrested Cleopatra's three youngest sons. When he met him, Cleopatra bluntly told him "I will not be paraded in triumph"—in ancient Greek: οὑ θριαμβεύσομαι, romanized: ou thriambéusomai— that, according to Livy, it is one of the few inscriptions of her exact words. Octavian promised to keep her alive, but gave her no explanation of his future plans for his kingdom. When informed by a confidant that he planned to transfer her and her children to Rome three days later, she chose suicide, as she had no intention of being exposed in a triumph like her sister Arsinoe IV. It is unclear whether Cleopatra's suicide in August 30 BC. C., at the age of 39, it took place in the palace or in her tomb. It is said that she was accompanied by her servants Eira (Iras) and Carmion (Charmion), who also took their own lives. Octavian was enraged by this outcome, but buried her with royal ceremonial next to Antony in her tomb. Cleopatra's physician, Olympus, does not explain the cause of her death, although popular belief is that she allowed an asp or cobra to Egyptian to bite and poison her. Plutarch narrates this story, but then suggests that an instrument was used (κνῆστις knêstis 'thorn, spike, grater') to introduce the toxin by scratching, while Dion says that he injected himself with the poison with a needle (βελόνη belonē) and Strabo advocates some sort of salve. a needle.

Cleopatra decided in her last moments to send Caesarion to Upper Egypt, perhaps planning to flee to Nubia, Ethiopia or India. Caesarion became Ptolemy XV, albeit for only 18 days until he is executed by order of Octavian on August 29, 30 BC. C., after returning to Alexandria under the false idea that it would allow him to be king. Octavio was convinced by the advice of the philosopher Arius Didymus that there was only room in the world for one Caesar. With the fall of the Ptolemaic kingdom, the Roman province of Egypt was established, marking the end of the Hellenistic period. In January 27 B.C. C. Octavian was named Augustus ("the revered") and accumulated constitutional powers that made him the first Roman Emperor, ushering in the Principate era of the Roman Empire.

Reign and role as monarch

Following the tradition of Macedonian rulers, Cleopatra ruled Egypt and other territories such as Cyprus as an absolute monarch, serving as the sole legislator of her kingdom. She was also its main religious authority, presiding over ceremonies dedicated to the deities of polytheistic religions both Egyptian and Greek. He oversaw the construction of several temples to the Egyptian and Greek gods, a synagogue for the Jews of Egypt, and even built Caesarius of Alexandria, dedicated to the celebration of the imperial cult of his patron and lover Julius Caesar..

She was directly involved in the administrative affairs of her domain, addressing crises such as famine by ordering the royal granaries to distribute food to the starving population during a drought early in her reign. Although the centralized economy she managed was more an ideal rather than a reality, his government attempted to impose price controls, tariffs, and a state monopoly on certain goods, fixed exchange rates for foreign currencies, and rigid laws that forced peasants to remain in their villages during planting seasons and harvest.

Apparently financial problems led Cleopatra to devalue her currency, which consisted of silver and bronze coins, but not gold coins like some of her distant Ptolemaic predecessors.

Lineage

Cleopatra belonged to the Greco-Macedonian dynasty of the Ptolemies, her European origins dating back to northern Greece. Through her father, Ptolemy XII Auletes, she was a descendant of two prominent somatophylakes from Alexander the Great of Macedonia: the general Ptolemy I Soter, founder of the Ptolemaic kingdom of Egypt and Seleucus I Nicator, the Greco-Macedonian founder of the Seleucid Empire of Western Asia. While Cleopatra's paternal branch can be traced through of her father, the identity of her mother is not known for sure. She was presumably the daughter of Cleopatra VI Tryphena (also known as Cleopatra V Tryphena), the cousin-wife or sister-wife of Ptolemy XII.

Cleopatra I Sira was the only member of the Ptolemaic dynasty who certainly introduced some non-Greek ancestry, being a descendant of Apama I, the Sogdian Persian wife of Seleucus I. It is generally believed that the Ptolemies they did not mix with the native Egyptians. Michael Grant states that there is only one known Egyptian mistress of a Ptolemy and no known wife, further arguing that Cleopatra probably had no Egyptian ancestry and that she "described herself as as Greek". Stacy Schiff writes that Cleopatra was a Greco-Macedonian with some Persian ancestry, arguing that it was rare for the Ptolemies to have an Egyptian mistress. American archaeologist Duane W. Roller believes that Cleopatra might have been the daughter of a a half-Greek-Macedonian, half-Egyptian woman from a family of priests devoted to Ptah (a hypothesis generally not accepted by the Cleopatra-minded scholarly community), but maintains that whatever Cleopatra's ancestry, she valued her Ptolemaic Greek ancestry more British historian Ernle Bradford wrote that Cleopatra did not challenge Rome as an Egyptian, "but as a cultured Greek".

An accusation that she was an illegitimate child was never leveled by Roman propaganda against her. Strabo was the only ancient historian to claim that children of Ptolemy XII born after Berenice IV, including Cleopatra, they were illegitimate. Cleopatra V (or VI) was expelled from the court of Ptolemy XII in late 69 BC. C. , a few months after the birth of Cleopatra, while the three minor children of Ptolemy XII were born in the absence of his wife.

The high degree of inbreeding among the Ptolemies is also illustrated by Cleopatra's immediate ancestry, a reconstruction of which is shown below. The family tree shown below also includes Cleopatra V, wife of Ptolemy XII, as the daughter of Ptolemy X Alexander I and Berenice III, which would make her a cousin of her husband, Ptolemy XII, but could have been the daughter of Ptolemy IX Látiro, which would have made her the sister-wife of Ptolemy XII instead Confusing accounts from ancient primary sources have also led scholars to identify Ptolemy XII's wife as Cleopatra V or Cleopatra VI; the latter may actually have been the daughter of Ptolemy XII and is used by some as an indication that Cleopatra V had died in 69 BC. C. instead of reappearing as co-ruler with Berenice IV in 58 B.C. C. (during the exile of Ptolemy XII in Rome).

| Ptolomeo V Epiphanes | Cleopatra I Sira | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ptolomeo VI Filométor | Cleopatra II | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ptolemy VIII Fiscon | Cleopatra III | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cleopatra Selene from Syria | Ptolemy IX | Cleopatra IV | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ptolomeo X Alejandro I | Berenice III | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cleopatra V Trifena | Ptolemy XII Auletes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cleopatra VII | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Legacy

Descendants

Right: A probable representation of Cleopatra Selene II, in relief on a silver plate with gold bread, early in the century I d. C.

His three surviving children, Cleopatra Selene II, Alexander Helios, and Ptolemy Philadelphus, were sent to Rome with Octavian's sister Octavia the Younger, their father's ex-wife, as their guardian. Cleopatra Selene II and Alexander Helios were present at Octavian's triumph in 29 BC. The fate of Alexander Helios and Ptolemy Philadelphus after this date is unknown. Octavia arranged for Cleopatra Selene II's betrothal to Juba II, son of Juba I, whose North African kingdom of Numidia had been converted. by Julius Caesar in a Roman province in the year 46 BC. C. for Juba I's support of Pompey. Emperor Augustus named Juba II and Cleopatra Selene II, after their wedding in 25. to. C., as the new rulers of Mauritania, where they transformed the ancient Carthaginian city of Iol into their new capital, renamed Caesarea Mauretaniae (today Cherchell, Algeria). Cleopatra Selene II brought many scholars, artists and advisers important members of her mother's royal court in Alexandria to serve her in Caesarea, now imbued with Hellenistic Greek culture. She also baptized her son Ptolemy of Mauretania, in honor of his Ptolemaic dynastic heritage.

Cleopatra Selene II died around 5 B.C. C., and when Juba II died in the year 23/24 d. He was succeeded by his son Ptolemy, however Ptolemy was eventually executed by the Roman Emperor Caligula in AD 40. C., perhaps under the pretext that Ptolemy had illegally minted his own royal coinage and had used iura regalia reserved for the Roman emperor. Ptolemy of Mauritania was the last known monarch of the Ptolemaic dynasty, although Queen Zenobia, of the short-lived Palmyrene Empire during the crisis of the 3rd century, would claim descent from Cleopatra.

Historiography and Roman literature

Although nearly 50 ancient works of Roman historiography refer to Cleopatra, they generally include only brief accounts of the Battle of Actium, her suicide, and Augustan propaganda about her personal failings. Despite not being a biography of Cleopatra Cleopatra, the Life of Antony written by Plutarch in the I century AD. C. as part of his Parallel Lives provides the most complete surviving narrative of Cleopatra's life. Plutarch lived a century after the Egyptian queen, but relied on primary sources, such as Philotas of Anfisa, who had access to Ptolemy's royal palace, Olympus, Cleopatra's personal physician, or Quintus Delius, a close confidant of Marco. Antony and Cleopatra. Plutarch's work includes both the Augustan vision of Cleopatra—which became canon in his day—and sources outside this tradition, such as eyewitness reports.

Judeo-Roman historian Flavius Josephus, I century AD. C., provides valuable information about Cleopatra's life through her diplomatic relationship with Herod I the Great. However, this work relies heavily on Herod's memoirs and the biased account of Nicholas of Damascus, tutor to Cleopatra's children in Alexandria before he moved to Judea to serve as counselor and chronicler at Herod's court. The Roman History published by the high official and historian Cassius Dio a early III century d. C., while not fully understanding the complexities of the late Hellenistic world, nevertheless provides a history of the era of Cleopatra's reign.

She is barely mentioned in De bello Alexandrino, the memoirs of an unknown officer who served under Caesar. The writings of Cicero, who knew her personally, offer a portrait unflattering of Cleopatra. The authors of the Augustan period Virgil, Horace, Propertius, and Ovid perpetuated the negative view of Cleopatra established by the ruling Roman regime, although Virgil instituted the idea of Cleopatra as a figure of romance and epic melodrama. Horace also considered Cleopatra's suicide as a positive alternative, an idea that was accepted in the late Middle Ages with Geoffrey Chaucer. Historians Strabo, Veleyus, Valerius Maximus, Pliny the Elder and Appian, although they did not offer accounts as complete as Plutarch, Josephus, or Dion, provided some details of her life that had not survived in other historical records. Inscriptions on contemporary Ptolemaic coins and some Egyptian papyrus documents reflect Cleopatra's point of view, but this The material is very limited compared to Roman literary works. The fragmentary Libyka commissioned by Cleopatra's son-in-law, Juba II, provides a glimpse of a possible body of historiographical material supporting Cleopatra's perspective.

The fact that she is a woman has perhaps led to her being a minor, if not insignificant, figure in ancient, medieval, and even modern historiography of the ancient Egyptian and Greco-Roman world. For example, historian Ronald Syme stated that she was not of much importance to Caesar and that Octavian's propaganda increased her importance to an excessive degree. Although Cleopatra was widely viewed as a promiscuous seductress, she had only two known partners, Caesar and Antony, the two most prominent Romans. who were most likely to ensure the continuity of her dynasty. Plutarch described her more as possessing a strong personality and charming wit than her physical beauty.

Cultural performances

In ancient art

Statues

Right: La Venus Esquilina, a Roman or helenoegipcia statue of Venus (Afrodita) that can be a representation of Cleopatra, exhibited at the Capitoline Museums.

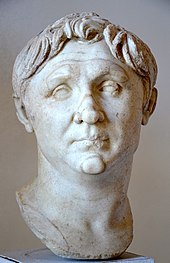

Cleopatra was depicted in various ancient works of art, both in the Egyptian, Hellenistic, and Roman styles. Existing works include statues, busts, reliefs, and minted coins, as well as ancient carved cameos, including one depicting Cleopatra and Antony in the Hellenistic style, today in the Altes Museum in Berlin. Contemporary images of Cleopatra were made both inside and outside of Ptolemaic Egypt. For example, a life-size gold-leafed bronze statue of Cleopatra existed inside the Temple of Venus Genetrix in Rome, the first time a living person had their statue placed side by side with that of a deity in a temple. Roman; it was erected there by Caesar and remained in the temple until at least the III century AD. C., perhaps preserved thanks to Caesar's patronage, although Augustus did not remove or destroy Cleopatra's artwork in Alexandria.

Among the surviving Roman statues, one of his in Roman style, life-size, was found near the Tomba di Nerone, Rome, on the Via Cassia and is now in the Museo Pio -Clementine, part of the Vatican Museums. Plutarch, in his Life of Antony, stated that the public statues of Antony were torn down by Augustus, but those of Cleopatra were preserved after his death thanks to because his friend Archibius paid the emperor 2,000 talents to dissuade him from destroying them.

Since the 1950s, scholars have debated whether the Esquiline Venus (discovered in 1874 on the Esquiline Hill in Rome and exhibited in the Palace of the Conservators of the Capitoline Museums) is or is not a depiction of Cleopatra, based on the statue's hairstyle and facial features, the apparent royal diadem she wears on her head, and the Egyptian cobra ureus coiled at the base. of this theory argue that the face of this statue is thinner than that of the Berlin portrait and claim that it was unlikely that she was depicted nude as the goddess Venus (or the Greek Aphrodite). However, she was depicted in a Egyptian statue as the goddess Isis, and some of her coins depict her as Venus-Aphrodite. Cleopatra was dressed as Aphrodite when she met Antony in Tarsus. The Esquiline Venus is generally regarded as a mid-century Roman copy I d. C. from a Greek original of the century I a. C. from the Pasiteles school.

In coins

Among the surviving coins from Cleopatra's reign we find pieces from all the years of her reign, from 51 to 30 BC. The only woman in the Ptolemaic dynasty to issue coins bearing her own name and effigy (which only she appears), Cleopatra almost certainly inspired her partner Caesar to become the first living Roman to display her portrait on a coin. Cleopatra was also the first foreign queen whose image appeared on a Roman coin. Coins dating from the period of her marriage to Antony, which also show her image, portray the queen with an aquiline nose and prominent chin very similar to her husband's. This similarity of facial features followed an artistic tradition depicting the harmony of a royal couple. Their strong, almost masculine facial features on these particular coins are markedly different from the softer, more delicate, and perhaps idealized images of her in Egyptian or Hellenistic styles. Her masculine facial features on minted coinage are similar to those of her father, Ptolemy XII Auletes, perhaps also to those of from his Ptolemaic ancestor Arsinoe II (316-260 BC. C.) and even to representations of earlier queens such as Hatshepsut and Nefertiti. -Macedonians who founded the Ptolemaic dynasty, to familiarize themselves to their subjects as a legitimate member of the royal house.

The inscriptions on the coins are written in Greek, although using the nominative case of Roman coins instead of the genitive case of Greek coins, as well as having the letters placed in a circular pattern along the edges of the coin in rather than across it horizontally or vertically as was the custom of the Greeks. These features of their coinage represent the synthesis of Roman and Hellenistic culture and perhaps also a statement to their subjects, however ambiguous to modern scholars, on the superiority of Antony or Cleopatra over others. Professor Diana Kleiner argues that Cleopatra, on one of her coins minted together with the image of her husband Antony, depicted herself as more masculine than in other portraits and more like an acceptable Roman client queen than a Hellenistic ruler. Cleopatra had already adopted this masculine aspect on coins before her relationship with Antony, such as those struck at the Ascalon mint during her brief period of exile in Syria and the Mediterranean Levant, something that Egyptologist Joann Fletcher explains as an attempt to resemble her father and as a legitimate successor to a male Ptolemaic ruler.

Various coins, including a silver tetradrachm minted sometime after her wedding to Antony in 37 BC. C., depicts her wearing a royal diadem and a 'melon-style' hairstyle. The combination of this hairstyle with a diadem also appears on two surviving sculpted marble heads. This hairstyle, with her hair braided back in a bun, it is the same one worn by her Ptolemaic ascendants Arsinoe II and Bernice II on their coins. After her visit to Rome in 46-44 to. C. it became fashionable for Roman women to adopt it as one of their hairstyles, but it was abandoned for a more modest and austere style during the conservative rule of Augustus.

Greco-Roman busts and heads

Of the surviving Greco-Roman busts and heads of Cleopatra, the sculpture known as "Cleopatra of Berlin", exhibited in the Antikensammlung Berlin collection of the Altes Museum, retains the complete nose, while the head known as "Cleopatra Vaticana", on display in the Vatican Museums, is missing her nose. Both wear royal diadems, have similar facial features, and perhaps once resembled the face of their bronze statue in the Temple of Venus Genetrix. Both date from the mid-century I a. C. and were found in Roman villas on the Appian Way in Italy, the Vatican in the Villa de los Quintili. Spanish professor Francisco Pina Polo believes that Cleopatra's coins present her image with certainty and claims that the sculptured portrait of the Berlin head has a similar profile with her hair in a bun, diadem, and hooked nose. A third sculptured portrait of Cleopatra, generally accepted by scholars as authentic, is kept in the Archaeological Museum of Cherchell, Algeria. This portrait shows the royal diadem and facial features similar to those of the Berlin and Vatican heads, but has a different hairstyle and may represent Cleopatra Selene II, daughter of Cleopatra. A possible Egyptian-style sculpture of Cleopatra in Parian marble wearing a headdress with a vulture is on display in the Capitoline Museums; found near a sanctuary of Isis in Rome and dated to the I a. C., is of Roman or Helleno-Egyptian origin.

Among other possible sculpted representations of Cleopatra is one on display at the British Museum in London, made of limestone, which may only represent a woman in her entourage during her journey to Rome. The woman in this portrait she has similar facial features to the others (including her pronounced hooked nose), but lacks a royal headband and sports a different hairstyle. However, it is possible that the head in the British Museum, which once belonged to a statue Complete, it depicts Cleopatra at a different stage in her life and also represents an attempt on her part to dispense with the use of the royal regalia (i.e., the diadem) in order to make her more attractive to the citizens of republican Rome. archaeologist Duane W. Roller is of the opinion that the head in the British Museum, along with those in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, the Capitoline Museums, and the private collection of Maurice Nahmen, albeit with facial features and hairstyles similar to those in the Berlin portrait but without a diadem royal court, they probably depict members of the royal court or even Roman women imitating Cleopatra's popular hairstyle.

Paintings

In the house of Marco Fabio Rufo in Pompeii, Italy, a mid-century wall painting I a. C. second Pompeian style of the goddess Venus holding a cupid near the great doors of the temple is most likely a depiction of Cleopatra as Venus Genetrix with her son Caesarion. The painting probably matches with the construction of the temple of Venus Genetrix in the forum of Caesar in September of 46 BC. , where Caesar had a bronze and gold leaf statue of Cleopatra erected. This statue was probably the basis for her depictions both in sculpted art and in this Pompeii painting. The woman in the painting wears a royal diadem on her head and is strikingly similar in appearance to the Vatican's Cleopatra, bearing possible marks in the marble on her left cheek where a cupid's arm may have come off. The room with the painting was boarded up by its owner, perhaps in reaction to Caesarion's execution in 30 BC. C. by order of Octavio, when the public representations of Cleopatra's son would have been inauspicious in the new Roman regime. Behind her golden diadem, crowned with a red jewel, is a translucent veil with wrinkles that they seem to suggest the queen's favored 'melon' hairstyle. Her ivory-colored skin, round face, long aquiline nose, and large round eyes were common features of the deities in both Roman and Ptolemaic representations. Roller states that "there seems to be no doubt that it is a depiction of Cleopatra and Caesarion before the gates of the Temple of Venus in the Forum Julium and, as such, it is the only surviving contemporary painting of the queen."

Another painting from Pompeii, early I century d. Housed in the house of Giuseppe II, it contains a possible depiction of Cleopatra with her son Caesarion, both wearing royal diadems as she lies back and takes poison in an act of suicide. The painting was originally believed to have been represented the Carthaginian noblewoman Sofonisba, who towards the end of the Second Punic War (218-201 BC) drank poison and committed suicide at the behest of her mistress Masinissa, king of Numidia. Among the arguments in favor of her being Cleopatra is the close relationship of her house with that of the royal family of Numidia, since Masinissa and Ptolemy VIII Fiscon were associated and Cleopatra's own daughter married the Numidian prince Juba II. Also, Sophonisba was a little-known figure when the painting was painted, while Cleopatra's suicide was much more famous. An asp does not appear in the painting, but many Romans believed that she had taken poison in site of a venomous snake bite. A set of double doors at the back, positioned high above the people in the painting, suggests the description of the layout of Cleopatra's tomb in Alexandria. A servant holds the mouth of an Egyptian crocodile (possibly an elaborate tray handle), while another standing man is dressed as a Roman.

In 1818, an encaustic painting, now missing, depicting Cleopatra committing suicide with an asp biting her bare chest, was discovered in the Temple of Serapis, in Hadrian's villa, near Tivoli, Italy. A chemical analysis carried out in 1822 confirmed that the material for the painting was composed of one third wax and two thirds resin. The thickness of the paint on Cleopatra's naked flesh and her cloths was similar to that of mummy portrait paints. from The Fayum. An 1885 steel engraving by John Sartain, depicting the painting described in the archaeological report, shows Cleopatra wearing Egyptian garb and jewelry from the late Hellenistic period, as well as the radiant crown of Ptolemaic rulers, as seen in their portraits on various coins minted during their respective reigns. After Cleopatra's suicide, Octavian commissioned a painting depicting her bitten by a snake, displaying it in her place during her triumphal parade in Rome. The death portrait of Cleopatra may have been one of the large number of works of art and treasures found in an Egyptian temple and brought to Rome by the Emperor Hadrian to decorate his private villa.

A Roman panel painting found in Herculaneum, Italy, from the I century AD. possibly depicting Cleopatra. She wears a royal diadem, red or auburn hair in a bun with pearlized hairpins, earrings with ball-shaped pendants, the white skin of her face and neck against a stark black background Her hair and facial features are similar to those in sculptured portraits from Berlin and the Vatican, as well as those on her coins. A very similar painted bust of a woman with a blue diadem in the so-called Garden House at Pompeii shows Egyptian-style imagery, such as a Greek-style sphinx, may have been the work of the same artist.

Portland Vase

The Portland Vase, a Roman glass vase with cameos dating to the Augustan period in the British Museum, shows a possible representation of Cleopatra with Antony. According to this interpretation, we would see Cleopatra grabbing Antony, pulling him towards her while a serpent (i.e., the asp) rises between her legs, Eros floats, and Anton, the presumed ancestor of the family, looks on in despair as his descendant Antony is driven to his doom. The Other Side of the Vase perhaps it shows a scene of Octavia, abandoned by her husband Antony but watched over by her brother, the Emperor Augustus. The vase would have been made no earlier than 35 BC. C. , when Antony sent his wife Octavia back to Italy and stayed with Cleopatra in Alexandria.

Native Egyptian Art

The Bust of Cleopatra on display at the Royal Ontario Museum represents an Egyptian-style bust of the queen. Dating to the mid-century I a. , is perhaps the earliest depiction of Cleopatra as a goddess and ruling pharaoh of Egypt. The sculpture has pronounced eyes that share similarities with Roman copies of Ptolemaic sculptured artwork. Dendera, near Dendera, Egypt, contains Egyptian-style relief-carved images along the outer walls of the Temple of Hathor depicting Cleopatra and her infant son Caesarion as an adult pharaoh and ruler making offerings to the gods. Augustus had his name inscribed there after Cleopatra's death.

A large three-foot-tall Ptolemaic black basalt statue in the Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg is believed to represent Arsinoe II, wife of Ptolemy II, but recent analysis indicates it may represent his descendant Cleopatra due to the three uraeus that adorn her headdress, compared to the two used by Arsinoe II to symbolize her rule over Lower and Upper Egypt. The woman in the statue also holds a double cornucopia divided (dikeras), which can be seen on the coins of Arsinoe II and Cleopatra. In his Kleopatra und die Caesaren (2006), Austrian archaeologist Bernard Andreae argues that this basalt statue, like other idealized Egyptian portraits of the queen, contains no realistic facial features and therefore adds little to our knowledge of her appearance. British historian Adrian Goldsworthy is of the opinion that, despite these depictions in the traditional Egyptian style, Cleopatra would only have dressed as a native "perhaps for certain rites" and would instead dress normally as a Greek monarch, including the Greek diadem seen on her Greco-Roman busts.

Medieval and early modern times