Classification of plants

The classification of plants arises from the need to obtain an order in the enormous diversity of plant organisms belonging to the Plantae kingdom and is resolved through classification systems.

Historically, the classification of plants was made according to the presence, absence and shape of fundamental organs, such as roots, stems, leaves, flowers and fruits, or according to the presence of one or two cotyledons at germination of the seed, as well as in the description of non-flowering plants and flowering plants.

Organization of classification systems

The classification systems have the form of dendrograms, each node of the dendrogram corresponds to a taxon (group of related organisms, with a common ancestor). Each taxon is assigned a taxonomic category. Nowadays, the proposal of each new taxon must be accompanied by a botanical name that follows the norms of the International Code of Nomenclature for Algae, Fungi and Plants (ICN).

History of classification systems

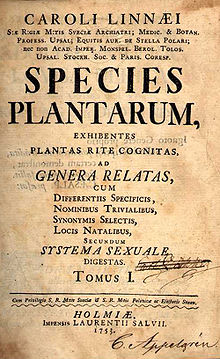

Rating is a discipline with a lot of historical background, because each new ranking is based on a previous ranking that users have become accustomed to. The first classification of plants on which science as we know it today was based was that of the ancient Greek Theophrastus (370 BC-285 BC), a disciple of Aristotle considered the father of Botany. Since the time of the ancient Greeks, science was not reborn in Europe until the late Middle Ages, at which time, in the first universities, botanists arose who reflected on the classification of species, guided by the discovery of new plants and new characters. Many classification systems arose around this time, both "natural" as artificial, but it was that of Carlos Linnaeus, in his historic book Species Plantarum ("The species of plants") in 1753, the one that transcended the most, mainly because it was the most complete. Botanists quickly began to use the names of the species described in that book to communicate with each other, so much so that in the later created International Code of Botanical Nomenclature it was considered (as it is still considered) the first book used as a reference for botanists. names of the taxa, leaving without effect the names applied to the plants before the appearance of that book. It is due to the founding effect of that book that species are called by binomial names, beginning with the genus name (although he was not the inventor of that nomenclature, which he took from an earlier classification system), and higher taxa species are called by uninominal names; and the system of taxonomic categories used today was also consolidated due to that book, categories that are called "linneanas" due to Linnaeus: species, genus, family, order, class, division, and kingdom (although he was not the inventor of several of those hierarchies, which he borrowed from earlier classification systems, and although some hierarchies were added later). Linnaeus considered his classification system "natural"; regarding the categories of species, genus and family; because in those categories he grouped species into taxa according to their morphological similarities. By doing this, he was also unknowingly grouping species based on their genetic, and ultimately evolutionary, similarities. Linnaeus's system was artificial above family, he did not believe that natural groups in such high categories existed, mainly due to the lack of data to observe similarities between groups in those categories at the time.

After the appearance of Linnaeus's book, many classification updates arose, and although some were more transcendent than others, none achieved the success of Linnaeus's book to prevail in communication, so many different classification systems began to be used.

Since Darwin's theory of evolution in 1859, scientists agreed that the phylogeny of species is a demonstration that species should be grouped according to "natural groups" as naturalists like Linnaeus had understood them. From that moment on, to build a classification, the phylogenetic tree was first assembled, and then the classification system was built on the basis of it. The problem at the time was that very little was known about what the "true" phylogenetic tree should be. For plants, there were only various hypotheses about the evolution of clades, which had weak support in the data and were sometimes very different from each other. That is why plant classification systems continued to flourish, with scientists not agreeing on which was closest to "reality."

This scenario changed abruptly in the 1990s and later, with the advent of molecular DNA analysis. This is because traits based on DNA molecules yield an enormous amount of highly reliable data, and both the powerful computers needed to analyze them and the ability to analyze that amount of data by statistical methods that had been published already existed. a few decades earlier. For the first time, a single phylogenetic tree hypothesis with broad consensus began to emerge, which is the one shown here.

The prevailing classification in the scientific environment today considers that only groups with a common ancestor can be taxa. For this reason, for example, dicots, which are paraphyletic, are not considered a taxon by most scientists, who divide them into taxa that correspond to their monophyletic groups.

Plant classification systems

Today it is widely agreed among scientists that you must start from the Archaeplastida or Primoplantae taxon to construct the monophyletic groups shown below, some important paraphyletic groups are also shown enclosed in quotation marks to distinguish them from monophyletic groups. It must be taken into account that although this part of the phylogenetic tree is well resolved, most scientists have not yet decided in which taxonomic categories to place these taxa, which is why here they are called with informal names or in general with names ending in -phyta ("plant", derived from ancient Greek) without going into detail about in which taxonomic category they should be placed.

Plantae (clade of primary chloroplast acquisition) also called Primoplantae or Archaeplastida

- Glaucophytes (Glaucophyta)

- Red seaweed (Rhodophyta)

- Green plants (Viridiplantae, Viridophyta or Chloroplastide)

- "Green algae" (paraphylical group, all Viridiplantae except Embryophyta)

- Clorophy (Chlorophyta)

- "Estreptophytes" (Streptophyta)

- "Carophytes" ("Charophyta") (paraphytic, all green algae not chlorophytes, the small groups that make up it will not be shown here, but we will mention the Charales, which is the group of which the earth plants originated)

- Land plants (Embryophyta)

- Bryophyta in broad sense

- Hepatic (Marchantiophyta)

- Antoceros (Anthocerophyta)

- Musgos (Bryophyta in the strict sense)

- Vascular plants or tracheoofitas (Tracheophyta, Cormophyta)

- "Pteridophyta" (paraphytic group comprising Lycopodiophyta and Monilophyta)

- Lycopodiophyta o Lycophyta

- Plants with megaphiles (Euphyllophyta)

- Goodies and related o monilofitas (Monilophyta)

- Equisetopsida = Equisetum)

- Deals

- Psilotopsida

- Marattiopsida

- Polypodiopsy

- Plants with seed, spermatophytes or fanerógamas (Spermatophyta)

- †"Seed ferns" ("Pteridospermatophyta", paraphiletic group, extinct)

- Gimnospermas (Gymnospermae)

- Conifers (Pinidae)

- Cicadas (Cycadidae)

- Ginkgo (Ginkgoidae)

- Gnetales (Gnetidae)

- Plants with flowers (Angiospermae, Magnoliophyta)

- Monocotlers (Monocotyledoneae)

- "Dicotyledoms" (Dicotyledoneae, paraphylaxis, all non-monocotyledon angiosperms)

- Goodies and related o monilofitas (Monilophyta)

- Bryophyta in broad sense

Phylogeny analyzes done in the last decades also achieved a high resolution below the categories mentioned in this scheme.

APG, APG II and APG III Angiosperm Classification System

First published by the group of botanists calling themselves the "Angiosperm Phylogeny Group" (APG) in 1998, for the second time (for which they named themselves "Angiosperm Phylogeny Group II", or APG II) in 2003, and for the third time for APG III in 2009, is a system classification of angiosperms. It was created out of the need to see advances in phylogeny derived from molecular DNA analysis reflected in a classification system for flowering plants. The curiosity of publishing under a group name and not as a list of authors, which is how it is normally done, was to avoid the problem of the authorship order of the work.

APW Angiosperm Classification System

The Angiosperm Phylogeny Website (APW or APWeb), created and updated by one of the APG members (P. F. Stevens), started from the APG II classification in 2003 and has been updating the classification with each publication since then. In 2003 it was a reflection of the APG II system, but over the years it has undergone modifications, and although it is the most unstable (since it is modified more regularly than the other systems) precisely for this reason it can be considered the closest to what is known today about angiosperm phylogeny.

Broadly speaking, APWeb (version 13 of 2015) classifies angiosperms into the following clades:

- Angiospermas

- Amborellales

- Nymphaeales

- Austrobaileyales

- Mesangiospermas

- Chloranthales

- Magnolide

- Monocots

- Ceratophyllales

- Eudicotas

Classification system of living gymnosperms by Christenhusz et al. 2011

Published in February 2011 [1], it recognizes four groups of living gymnosperms to which the rank of subclass is assigned: Cycadidae, Ginkgoidae, Gnetidae, and Pinidae. The authors follow the recommendation of Chase & Reveal [2], in the sense of assigning the class rank to land plants and the subclass rank to the main clades included. The position of Gnetidae is recognized to be problematic. If the "gnepine" continue to gain strength, the authors do not propose a merger of the Gnetidae and Pinidae subclasses, but rather the formation of a fifth subclass that would include non-Pinaceae conifers.

| Eichler 1886 Gymnospermae | Wettstein 1935 Gymnospermae | Cronquist et al. 1966 Pinophyta | Kubitzki1990 | Margulis et al. 1998 ITIS 2014 | Christenhusz et al 2011, ICBN | APWeb 2015 Gymnosperms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cycadaceae | Cycadinae | Cycadicae | Cycadopsy | Cycadophyta | Cycadidae | Cycadales |

| Coniferae | Coniferae | Pinicae | Pinopsida | Coniferophyta | Pinidae | Pinales (?P) |

| Ginkgoinae | Ginkgoopsida | Ginkgophyta | Ginkgoidae | Ginkgoales | ||

| Gnetaceae | Gnetinae | Gneticae | Gnetopsida | Gnetophyta | Gnetidae | Gnetales |

Christenhusz et al.'s fern and related classification system. 2011

The Christenhusz et al. 2011 is the one currently used for the classification of ferns in the broadest sense (monilophytes and lycophytes).

The system is an update of an earlier one, the Smith et al. 2006. First published in August 2006, like the APG II system, it is a classification system created due to the need to see advances in fern phylogeny reflected in a plant classification system. It classifies what today is called "ferns" (clade Monilophyta), in classes, orders and families. The authors of the system clarify that the genera and species at the molecular level have not yet been sufficiently investigated, so it is not yet time to create a classification system below the genus category, and in fact some families are still poorly defined..

| Eichler 1886 | Engler 1924 | G. Smith 1955 | A. Smith 2006 | Christenhusz et al 2011, ICBN | Informal name | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equisetinae | Sphenopsida | Calamophyta | Monilophyta | Equisetopsida | Equisetidae | balances |

| Filicinae | Filicopsida | Pterophyta | Polypodiopsy | Polypodiidae | leptoporangi ferns | |

| Marattiopsida | Marattiidae | eusporangized ferns | ||||

| Psilotopsida | Ophioglossidae | of the | ||||

| Lycopodinae | Psilotopsida | Psilophyta | psilots | |||

| Lycopsida | Lepidophyta | Lycophyta | Lycopodiidae | lypod | ||

System of the Catalog of Life (Ruggiero el al. 2015)

It belongs to the Catalogue of Life or (CoL) is a collaborative project that develops one of the most recent taxonomies for all living beings, seeking to establish a manageable and practical classification, which admits some paraphyletic groups and collects part of the Cavalier-Smith postulates.

The most important levels of the plants within an overview of this system are the following:

- Eukaryota

- kingdom Plane

- Biliphyta

- phylo Glaucophyta

- Filo Rhodophyta

- Sub-rein Viridiplantae

- Chlorophyta

- subfilo Chlorophytina

- subfilo Prasinophytina (P)

- Streptophyta

- Superfilo Charophyta (P)

- Superfilo Embryophyta

- Filo Anthocerotophyta

- Filo Bryophyta

- Row Marchantiophyta

- Tracheophyta

- subfilo Lycopodiophytina

- subfilo Polypodiophytin (monilofites)

- subfilo Spermatophytina

- superclass Angiospermae

- superclass Gymnospermae

- Chlorophyta

- Biliphyta

- kingdom Plane

Outdated rating systems

Before the advent of molecular DNA analysis, other classification systems existed. Here are three of the most used at the time, which can still be found by ordering the taxa of many Floras.

The Eichler classification system. Published by August Wilhelm Eichler in 1883 and 1886, it was a precursor to modern taxonomy and was adapted many times by other researchers. He was one of the first who tried to be phylogenetic.

Engler's system of classification. First published by Adolf Engler in the late 19th century and continued by his collaborators, and adapted several times by other taxonomists (thus having numerous variants).

The Cronquist classification system. First published by Arthur Cronquist in 1966 and continued in 1981 and 1988, focusing primarily on angiosperms, it was probably the most widely used in the 1980s, until the advent of the APG system. It was mainly based on morphology, and accepted paraphyletic taxa.

As a historical reference, the following is Eichler's 1883 botanical taxonomy. The phylum and classes of Thallophyta were polyphyletic, the other groups are paraphyletic or monophyleticː

- A. Cryptogamae

- phylum I. Thallophyta

- classis I. Algae

- classis II. Fungi

- classis III. Lichenes

- phylum II. Bryophyta

- classis I. Hepaticae

- classis II. Musci

- phylum III. Pteridophyta

- classis I. Equisetinae

- classis II. Lycopodinae

- classis III. Filicinae

- phylum I. Thallophyta

- B. Phanerogamae

- phylum I. Gymnospermae

- phylum II. Angiospermae

- classis I. Monocotyleae

- classis II. Dicotyleae

- subclassis I. Choripetalae (non-steroided)

- subclassis II. Sympetalae

References Cited

[1] Christenhusz, M.J.M. et al. (February 18, 2011) A new classification and linear sequence of extant gymnosperms. Phytotaxa 19: 55–70.

[2] Chase, M.W. & Reveal, J.L. (2009) A phylogenetic classification of the land plants to accompany APG III. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 161: 122–127.

Contenido relacionado

Hippocastanaceae

Gastridium

Crypsis