Church of Santa Maria de Melque

Santa María de Melque is a Visigothic monastic complex located in the municipality of San Martín de Montalbán, in the province of Toledo (Spain). It is located 30 km south of the provincial capital, equidistant from the towns of La Puebla de Montalbán and Gálvez, between the Ripas stream and the Torcón river, which is a tributary of the left bank of the Tagus river.

Currently, you can visit the church, which occupies the center of the complex, and the interpretation center that has been installed in the adjoining rooms, also restored. The landscape that can be seen from Santa María is also characteristic of the area.

History

Santa María de Melque was born as a monastic complex in the VII and VIII in the vicinity of what was the capital of the Visigothic kingdom, Toledo. Its initial construction date is very old, from the VII century, which coincides with the end of the Visigothic kingdom. Radiocarbon dating of a sample of esparto grass obtained from the surviving part of the original stucco plaster has given a more probable date of construction in the interval 668-729 A.D. Its construction probably stopped when the arrival of the Arabs began and was completed. and it was later reformed, having suffered multiple historical vicissitudes.

Originally, there was a Roman villa with five dams on the two streams that surround the rocky mound. Then the monastery was built with buildings organized around the church.

The Muslim conquest of the Iberian Peninsula did not immediately end this monastic nucleus, as there are testimonies of the survival of a Mozarabic community that later disappeared. Its buildings were used as an urban nucleus and its church was fortified with the construction of a tower on the dome of the church, a tower that is still preserved. Rainwater and torrent water was dammed by dams located on either side of the complex.

With the conquest of Toledo by King Alfonso VI of León in 1085, the temple recovered its liturgical function without losing its military function. The anthropomorphic tombs located to the East and the remains of barbicans that are preserved are testimonies of this historical period.

In 1148 it appears mentioned —with the name of Santa María de Balat Almelc— in the bull of Pope Eugenio III that establishes the limits of the archdiocese of Toledo after the reconquest of the city (bull given in Reims on the 16th of April 1148). It is also mentioned in the Topographic Relations of Felipe II (1575, in the chapter dedicated to La Puebla de Montalbán) and in the Descripciones of Cardinal Lorenzana (1784), in both cases already with the current name de Melque and described as a rural hermitage to which the residents of La Puebla de Montalbán made a pilgrimage once a year (pilgrimage).

The small population center survived well into the XIX century, taking advantage of the monastic buildings for farmhouse uses. The confiscation of Mendizábal ended with the cult, all its buildings being used as stables and barns.

In 1968 the Provincial Council of Toledo acquired the complex and restored it, rehabilitating the church and also the adjoining buildings where the interpretation center of Santa María and the Visigothic world was installed. In one of its rooms you can still see a long manger built with materials from the monastic complex itself. It is expected to continue working on the recovery of the dams, the fence and the Visigothic settlement.

The church

It was built in the first half of the VIII century and is one of the best-preserved monuments of early medieval Spain. Its construction technique is a direct heritage of late Roman architecture.

However, the few surviving decorative elements (stucco filigrees on the central arches of the transept) link it to Eastern Christian influences from what is now Syria or Jordan. The large arcosolio (arco = arch; solio = sarcophagus) that can still be seen at the bottom of the southern arm of the transept, suggests that Melque could originally have been a mausoleum intended for the burial of a high-ranking personage of the Visigothic Kingdom of Toledo. Later, the church was reformed at least twice.

The Templars of the Reconquista turned the church into a defensive tower, transforming it into a Roman-style turris. This tower on the dome has recently been dismantled. It had a porch with three openings, now disappeared.

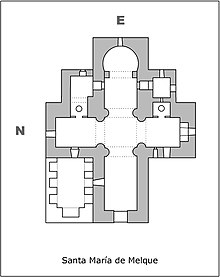

The plan is cruciform, with a central apse; the two side apses were added later. Its different naves, some side chapels and a room with very pronounced horseshoe arches have been preserved intact. There is also a niche probably of the founder of the temple, as already indicated.

The presbytery is wide as befits a monastic community and on both sides of it can be seen flattened semicircular arches. On the vault, the Muslim tower is preserved, which was accessed by an external staircase.

Its factory is made of enormous dry-assembled granite blocks, reminiscent of the Segovia aqueduct. The molding is calculated in Roman cubits and is similar to that of San Pedro de la Mata, also in Toledo, or that of San Miguel de los Fresnos, in Badajoz.

This church has clearly Visigothic style contributions and new solutions provided by the Mozarabs, and also memories of the Roman style:

- Visigoths: the horseshoe arch that holds the apse vault, which exceeds 1⁄3 of the radius. The devoid set of sculpted remains, of visigod tradition. The rainbow.

- Mozarabic bearings: central horseshoe arches over 1⁄2 of the radius. Arches of windows in 2⁄3. The strange semi-circular pilasters of the interior, which cannot be considered attached.

- Innovations: the circular slide of the corners on its four facades plus the vertical cleft on both sides, giving the appearance of pseudocolumns. They look like columns located in the corners of the Norman Romanesque-style lantern towers. It's an unprecedented solution.

- Roman style: the huge blocks of granite, the moulding in Roman elbows, its plant that can be compared with the mausoleum of Gala Placidia in Rávena, Italy.

It is a Visigothic building from the chronological point of view, but with protomozarabic solutions.

Legend of Solomon's Table

The researcher José Ignacio Carmona Sánchez, in his historical study Santa María de Melque and Solomon's treasure, points out how there is total unanimity on the part of historians regarding the Table of Solomon in what following:

- If there was a table called Solomon, it was none of those found after the Arab invasion, as is evident from the most authoritative sources; proof of this is that in the later centuries many main people like Philip II continued their search.

- Until the last moment, the godo clan supporting the invasion did not fear the relics, because far from seeing the Arabs as a threat, they expected to be restored to the throne.

- The Visigoths concealed not a few of their treasures and secrets in sarcophages, burials and caves associated with constructions, as deduced by subsequent discoveries.

- The losing Visigoth clan, being surprised by the rapid advance of the Muslims, improvised the way out, carrying with it the objects of importance, as related to the famous ark of the relics, which ended in a cave outside Oviedo. The concealment in the proximity of the capital points to an excess of confidence and could well be carried out by any of the clans; by the victorious clan because it would not trust the Arabs until they were restored; by the defeated clan because it could rely on the transientness of the constant alternations and struggles of power in the visigod world.

- The natural way out of Toledo would go in the direction of the mountains of Toledo, where there were ancient Roman roads that facilitated the flight, as confirmed by the trajectory and location of the treasure of Guarrazar.

- In the same trajectory of the town where the treasure of Guarrazar (Guadamur) appeared, and just a few kilometers away, one of the oldest and most unknown churches in Spain is found, not by chance. This church has all the reasonable elements of probability: an arcsolio, an intricate network of underground galleries, a subsequent link to the Order of the Temple and legends and traditions that relate it to the temporary treasures.

Louis Charpentier gives the example of Dormelle (Seine-et-Marne), a very spacious basement with a brick vault and the shape of a cradle that communicated, taking the direction of Paley, with a sister Templar commendation. In the castle of Montalbán, its basements are functionally anachronistic and bear an almost absolute resemblance to Charpentier's description.

Some of these objects could be located in the surroundings of the castle of Montalbán and the church of Santa María de Melque, in Toledo:

The church of Santa Maria de Melque was an ideal place to hide any treasure, due to the existence on its outskirts of an intricate network of galleries that is projected to the nearby Castle of Montalban.[... ]

The plot of the Grail has its turning point in Toledo, through Flegetanis, not by chance "of Solomon's lineage". Only in Toledo could pure men be found, that is, those of the "Saco of Benjamin", the purest Jewish aristocracy, the avid custodians of the sacred objects of the Jewish people. The Castle of Montalban (Montsalvat?) finds its prominence regardless of whether in its bowels, communicated with the church of Santa Maria de Melque, there is a stone called Grial or Table of Solomon.Saint Mary of Melchized and the Treasure of Solomon. José Ignacio Carmona Sánchez, 2011.

References and notes

- ↑ Knight et al. (1999). «Notes about the productive complex of Melque (Toledo)». Spanish Archive of Archaeology 72: 199-239.

- ↑ Fita Colomè, Fidel (1885). «Santuario de Atocha (Madrid). Unpublished buds of the centuryXII». Bulletin of the Royal Academy of History 7: 215-226.

- ↑ Balat Almelc can be The Way of the King in Arabic, perhaps a reference to its proximity to the XXV track of the Itinerary of Antonino (Cesaraugusta-Toletum-Emérita), of singular importance in Visigothic times.

- ↑ Viñas Mey, Carmelo; Paz, Ramón (1951). Historical-geographic-statistical relations of the peoples of Spain made by Felipe II: The Kingdom of Toledo (second part). Madrid: CSIC. p. 258.

- ↑ a b Saint Mary of Melchized and the treasure of Solomon.

- ↑ Carmona Sánchez, José Ignacio (1970). The mystery of the Templars. Bruguera. ISBN 978-84-95690-94-4.

- ↑ Max Heindel (1992). Rosacruz Dictionary. Editorial Kier. ISBN 97895017717. Consultation on 9 July 2011. "The mystery of the Holy Grail was administered by a group of saints who lived in the castle of Montsalvat, gentlemen whose purpose was to communicate to mankind great spiritual truths. »

Contenido relacionado

Tate Modern

Indonesian history

Swiss flag